A Comprehensive Guide to CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Screening: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to design, execute, and validate genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens.

A Comprehensive Guide to CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Screening: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to design, execute, and validate genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens. It covers foundational principles of CRISPR screening, detailed step-by-step protocols for pooled library screening using lentiviral delivery, critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenging cell models, and robust methods for hit confirmation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing current best practices and recent technological advances, this guide empowers scientists to systematically uncover gene function and identify novel therapeutic targets with high confidence and reproducibility.

Understanding CRISPR-Cas9 Screening: Principles and Evolution of Genetic Perturbation

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system, derived from a natural immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, has been repurposed as a powerful genome engineering tool [1]. This adaptive defense system allows bacteria to incorporate DNA fragments from invading bacteriophages into their genome, which are then used to recognize and cleave foreign genetic material during subsequent attacks using the Cas9 enzyme [1]. The groundbreaking work by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, which earned them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, involved engineering this system into a versatile gene-editing tool by creating a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the DNA-cutting process [1]. This innovation laid the foundation for modern genome engineering, with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout becoming an indispensable technique for studying gene function in disease and developing novel gene therapy modalities.

In the context of drug discovery and basic research, CRISPR knockout serves as a critical tool for functional genomics, allowing researchers to determine gene function by observing the phenotypic consequences of gene disruption [1]. The core mechanism involves using the Cas9 nuclease to create targeted double-strand breaks in DNA, which when repaired by the cell's natural repair machinery, often results in gene disruptions or "knockouts" that abolish the function of the targeted gene. This approach has been successfully applied across various biological systems, from industrial cell line engineering to the development of transformative therapies like Casgevy, the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease [1].

Molecular Mechanisms of Cas9-Induced DNA Cleavage

CRISPR-Cas9 System Components

The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two fundamental molecular components that work in concert to achieve targeted DNA cleavage. The first is the Cas9 endonuclease, a multifunctional enzyme with DNA-cutting capabilities. The second is the single-guide RNA (sgRNA), a synthetic RNA molecule that combines two naturally occurring RNA components: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which specifies the target DNA sequence through complementary base pairing, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a structural scaffold that mediates Cas9 activation and stabilizes the complex for efficient target binding [1].

The process of DNA recognition and cleavage begins with the formation of a complex between Cas9 and the sgRNA. This ribonucleoprotein complex scans the genome searching for a specific DNA sequence adjacent to the target site known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [1]. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide [1] [2]. Once the Cas9-sgRNA complex identifies a PAM sequence, it initiates local DNA unwinding, allowing the sgRNA to check for complementarity with the adjacent DNA sequence. If the target DNA sequence is fully complementary to the sgRNA guide sequence, the Cas9 enzyme undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains [3].

The Cas9 enzyme contains two distinct nuclease domains: the HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the sgRNA, and the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary strand [3]. These coordinated cleavage events result in a double-strand break (DSB) precisely 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [1]. Recent research using advanced profiling methods like BreakTag has revealed that Cas9 can cleave DNA in both blunt-end configurations and staggered configurations (creating overhangs), with approximately 35% of SpCas9 DSBs being staggered [2]. The specific configuration of the break is influenced by DNA:gRNA complementarity and the use of engineered Cas9 variants, with staggered breaks being particularly associated with predictable single-nucleotide insertions during repair [2].

DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

Once Cas9 induces a double-strand break, the cell activates one of two major DNA repair pathways to repair the damage. The choice between these pathways ultimately determines the editing outcome and is crucial for achieving successful gene knockout.

The Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway is the dominant and more error-prone repair mechanism in most mammalian cells [1]. NHEJ functions throughout the cell cycle and operates by directly ligating the broken DNA ends without requiring a repair template. This process often results in small random insertions or deletions of nucleotides at the cleavage site, collectively known as "indels" [1] [4]. When these indels occur within the protein-coding region of a gene, they can cause frameshift mutations that disrupt the reading frame, leading to premature stop codons and ultimately resulting in a loss-of-function mutation – the fundamental goal of CRISPR knockout [4]. The error-prone nature of NHEJ makes it the preferred pathway for creating gene knockouts, as these random insertions and deletions effectively disrupt the gene's coding capacity.

The alternative repair pathway, Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), is a more precise mechanism that requires a homologous DNA template to faithfully repair the break [1]. HDR is active primarily in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when sister chromatids are available to serve as repair templates. In CRISPR applications, researchers can exploit this pathway by providing an exogenous donor DNA template containing desired modifications flanked by homology arms matching the sequences surrounding the cut site [4]. While HDR offers the potential for precise genome editing, including gene corrections or specific insertions, it occurs at significantly lower efficiency compared to NHEJ in most experimental systems [4]. This lower efficiency presents a major challenge for applications requiring precise edits, though protocols combining p53 inhibition with pro-survival small molecules have achieved homologous recombination rates exceeding 90% in induced pluripotent stem cells [5].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Repair Template | Not required | Requires homologous DNA template |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout all phases | Primarily S and G2 phases |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (generates indels) | High-fidelity |

| Efficiency in Mammalian Cells | High (dominant pathway) | Low (typically <10%) |

| Primary Application in CRISPR | Gene knockout | Precise gene editing, insertion |

| Outcome | Random insertions/deletions | Precise, predetermined sequence change |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Knockout

sgRNA Design and Validation

The foundation of a successful CRISPR knockout experiment lies in the careful design and validation of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs). Proper sgRNA design is critical for ensuring target efficiency, maximizing on-target activity, and minimizing off-target effects [1]. The sgRNA design process begins by identifying a PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) downstream of the desired target sequence [1]. The 20-nucleotide targeting sequence should be selected immediately upstream of the PAM. Optimal sgRNAs should have a guanine-cytosine (GC) content between 40-60% for maximum stabilization of the DNA-sgRNA complex, which helps mitigate off-target binding [1].

Several computational tools and libraries have been developed to facilitate sgRNA design, overcoming the limitations of manual selection. These tools provide pre-designed gRNAs with information on on-target and off-target scores for various organisms, including humans, mice, rats, zebrafish, and C. elegans [1]. When designing sgRNAs, it's crucial to select guides with low similarity to other genomic sites to minimize off-target activity. Guide design software such as CRISPOR employs specialized algorithms for CRISPR off-target prediction, typically providing a CRISPR off-target score or ranking based on the predicted on-target to off-target activity ratio [6]. High-ranking gRNAs will have high on-target activity and lower risk of off-target editing. Additional strategies to minimize off-target effects include using modified gRNAs with 2'-O-methyl analogs (2'-O-Me) and 3' phosphorothioate bond (PS) modifications, which reduce off-target edits while increasing editing efficiency at the target site [6].

Table 2: Key Considerations for sgRNA Design and Optimization

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Impact on Editing |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 40-60% | Higher stability of DNA:RNA duplex |

| Guide Length | 20 nucleotides or less | Reduces off-target activity |

| PAM Proximal Region | Perfect complementarity | Critical for R-loop formation and cleavage |

| Off-target Score | Varies by algorithm | Predicts specificity; higher scores indicate better specificity |

| Chemical Modifications | 2'-O-Me, PS bonds | Reduces off-target effects, increases nuclease stability |

| Target Complexity | Higher Shannon index | Reduces off-target activity [2] |

Delivery Methods for CRISPR Components

The success of CRISPR genome editing depends not only on successful sgRNA design but also on the efficient delivery of the system to target cells. Multiple delivery methods have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations depending on the target cell type and application.

Electroporation involves treating cells with pulses of electric current to increase membrane permeability, allowing CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes to enter the cells [1]. This method is particularly beneficial for delivering the RNP with single-stranded donor DNA for homology-directed repair and offers the advantage of transient Cas9 exposure, reducing the risk of off-target effects. Microinjection provides direct physical delivery of CRISPR components into cells but is low-throughput and technically demanding [1].

Engineered viral vectors, particularly lentiviral and adenoviral vectors, can transduce sgRNA and Cas enzyme genes to the host [1] [4]. Lentiviral vectors enable stable integration into the genome, allowing long-term expression, while adenoviral vectors are efficient for transient expression without genomic integration [6]. However, viral delivery carries the caveat that Cas genes can integrate into the host genome and produce undesired changes, including prolonged Cas9 expression that increases off-target risks [1].

Nanoparticle-based delivery represents a promising non-viral approach. Lipid-based nanoparticles (LNP) can encapsulate RNP or plasmid DNA for delivery via lipofection [1]. LNPs reduce the risk of prolonged Cas9 expression, thereby minimizing off-target effects. Other nanomaterials, including gold and zinc nanoparticles, have also demonstrated high delivery efficiency [1]. The choice of delivery method significantly impacts editing efficiency and specificity, with RNP delivery generally providing the shortest window of Cas9 activity, making it ideal for reducing off-target effects [6].

Analytical Characterization of Knockout Clones

Following CRISPR-Cas9 delivery and selection, comprehensive characterization of the resulting knockout clones is essential to confirm successful gene editing and understand its functional consequences. Characterization occurs at multiple levels, from genomic sequence analysis to phenotypic assessment.

Genomic screening of knockout clones helps determine targeting efficiency and the functional impact of genomic modifications. Several methods are commonly employed: Sanger sequencing with chromatogram analysis allows direct sequencing of the target region and is accessible for low-throughput applications [1]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides high-throughput sequencing of clones to identify indels, large deletions, and complex mutations across many samples simultaneously [1]. The BreakTag method represents an advanced NGS-based approach for profiling Cas9-induced DNA double-strand breaks genome-wide, enabling comprehensive analysis of both on-target and off-target activities [2]. Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) measures mRNA expression levels of the target gene to confirm loss of gene expression [1].

Phenotypic screening assesses the protein expression and cellular functions of knockout clones. Flow cytometry, ELISA assays, and Western Blots can screen for the presence or depletion of proteins and provide quantifiable protein expression levels [1]. Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry offer visual confirmation of gene knockout by demonstrating the absence of the target protein [1]. Arrayed CRISPR libraries enable high-throughput phenotypic screening through viability assays and fluorescent detection of proteins encoded by the target genes [1]. Functional assays, such as the phagocytosis assay used in pooled CRISPR screens for human iPSC-derived microglia, can link genetic perturbations to specific cellular phenotypes [7].

Advanced Applications in Research and Therapy

Drug Discovery and Functional Genomics

CRISPR knockout technology has revolutionized functional genomics and drug discovery by enabling systematic investigation of gene function. In cancer research, CRISPR screens are commonly used to identify genes central to tumorigenic pathways, including proliferation, metastasis, and immune evasion [1]. A 2022 Cell study used high-throughput knockout experiments to identify genes involved in immunosuppression, revealing that loss of function of the TGFβ receptor 2 (Tgfbr2) gene conferred immune resistance and growth advantage to lung tumors [1]. Similarly, a 2024 Nature study focusing on regulators of aging in neural stem cells identified Slc2a4, encoding a glucose transporter, as a key factor that decelerates neural stem cell activation and contributes to cognitive decline during aging [1].

The application of CRISPR screening has expanded to more physiologically relevant models, including primary human 3D organoids. Recent studies have demonstrated large-scale CRISPR-based genetic screens in human gastric organoids to systematically identify genes that affect sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents like cisplatin [8]. These screens in 3D organoid models, which better preserve tissue architecture and cellular heterogeneity, have uncovered novel gene-drug interactions, including an unexpected link between fucosylation and cisplatin sensitivity, and identified TAF6L as a regulator of cell recovery from cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity [8].

Therapeutic Applications

The therapeutic potential of CRISPR-Cas9 knockout is exemplified by the FDA approval of Casgevy (exa-cel), the first CRISPR-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia [1] [6]. This landmark treatment works by isolating hematopoietic stem cells from patients, using CRISPR/Cas9 to disrupt the BCL11A gene – a repressor of fetal hemoglobin production – and reinfusing the edited cells back into patients, enabling production of functioning hemoglobin [1].

Several knockout strategies are currently under development for cancer therapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, transcription factors, and signaling proteins are common CRISPR targets [1]. Preliminary research has shown that knocking out the programmed cell death protein 1 gene (PD-1), which inhibits T cell activation, can reactivate killer T cells to combat tumor cells [1]. The expanding therapeutic pipeline includes treatments for various genetic disorders, with careful consideration of delivery methods and safety profiles tailored to each application.

Industrial Biotechnology

CRISPR-Cas9 gene knockout has significantly advanced industrial biotechnology and synthetic biology applications. In the development of industrial cell lines for biotherapeutic production, knockout combined with homologous recombination is employed to disrupt endogenous gene function, establishing stable and durable clones with high production rates [1]. For example, in the engineering of Komagataella phaffii (formerly Pichia pastoris), a yeast species widely used for recombinant protein production, CRISPR knockout has been applied to disrupt multiple protease genes (pep4 and prb1) to minimize protein degradation and enhance yields of target biologics [9]. Simplified methods using knockout fragments with short homology arms (30-50 bp) have enabled rapid and efficient gene disruption without the need for subcloning or sequencing-based screening, significantly accelerating the strain engineering process [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Knockout Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target DNA sites | SpCas9, HiFi Cas9 variants [5] [6] |

| sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Synthetic sgRNAs, with optional chemical modifications [6] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Electroporation systems, lipid nanoparticles, viral vectors [1] |

| HDR Templates | Enables precise gene editing via homologous recombination | ssODNs, double-stranded donor templates [4] [5] |

| Validation Tools | Confirms editing efficiency and specificity | ICE analysis, NGS, Western blot antibodies [6] [3] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Enhances cell survival post-editing | CloneR, Revitacell, Alt-R HDR enhancer [5] |

| Plasmid Resources | Source of CRISPR machinery | Addgene repository, Santa Cruz Biotechnology [4] [3] |

Technical Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

Despite its transformative potential, CRISPR-Cas9 knockout faces several technical challenges that must be addressed for both research and clinical applications. Off-target effects represent a primary concern, where Cas9 cleaves at unintended genomic sites with sequence similarity to the target [1] [6]. These off-target edits can confound experimental results and pose significant safety risks in therapeutic contexts, particularly if they occur in oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes [6]. Strategies to minimize off-target activity include using high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9), optimizing sgRNA design to maximize specificity, employing modified sgRNAs with chemical alterations, and selecting appropriate delivery methods that limit the duration of Cas9 expression [1] [6].

Genomic instability represents another significant challenge, as excessive double-strand breaks can lead to large deletions, chromosomal rearrangements, or activation of DNA damage response pathways, including p53-mediated apoptosis [1] [5]. Innovative approaches to mitigate these concerns include using Cas9 nickase variants (Cas9n) that create single-stranded breaks instead of double-strand breaks [1]. By using two Cas9n enzymes with two sgRNAs targeting opposite strands, researchers can generate staggered breaks that mimic DSBs but with enhanced specificity [1]. Additionally, p53 inhibition combined with pro-survival small molecules has been shown to significantly improve cell survival and editing efficiency in challenging cell types like induced pluripotent stem cells [5].

Advanced screening methods have been developed to comprehensively assess both on-target and off-target activities. The BreakTag method enables systematic profiling of Cas9-induced DNA double-strand breaks at nucleotide resolution, allowing researchers to map cleavage sites genome-wide and identify determinants of Cas9 incision specificity [2]. Other methods like GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, and DISCOVER-seq provide complementary approaches for nominating and validating off-target sites, while whole genome sequencing remains the gold standard for comprehensive analysis of CRISPR editing outcomes, including detection of chromosomal aberrations [2] [6].

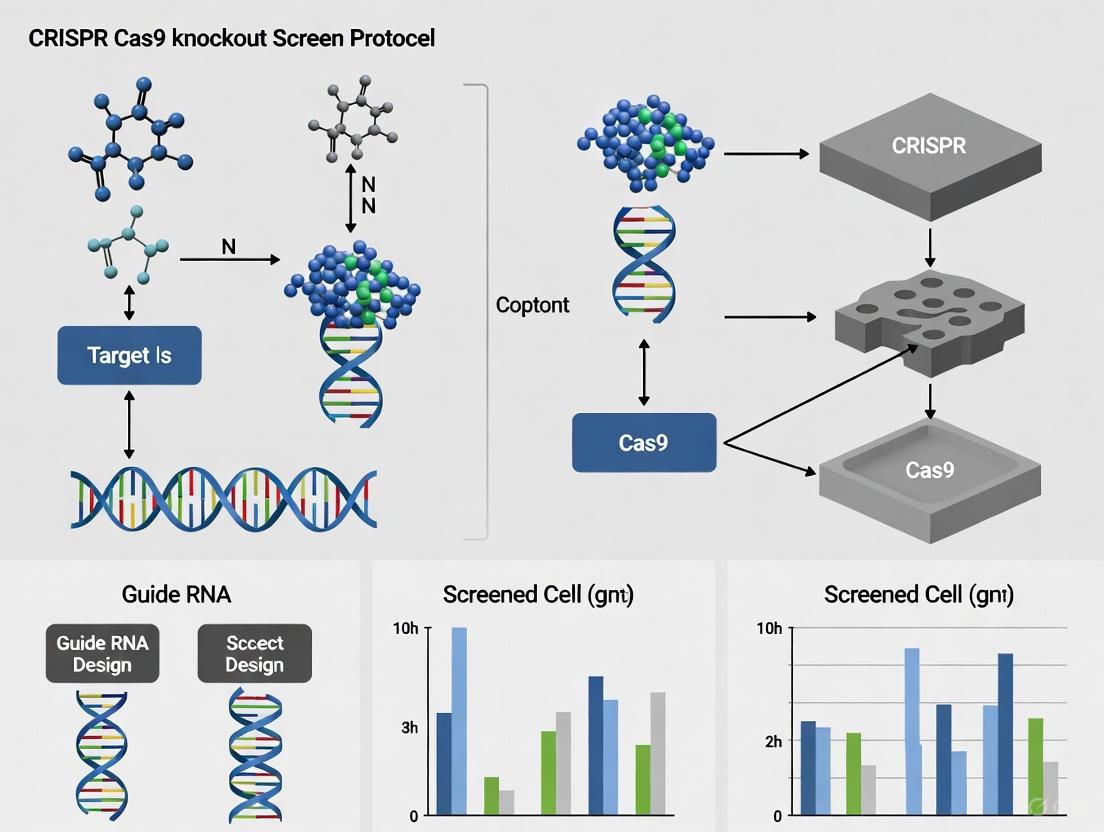

CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (CRISPRko) screening has emerged as a powerful functional genomics tool for the unbiased discovery of gene function and therapeutic targets. This technology utilizes a library of guide RNAs (gRNAs) that direct the Cas9 nuclease to create targeted double-strand breaks in the genome, resulting in loss-of-function mutations. The core principle involves systematically perturbing thousands of genes in parallel and selecting for phenotypes under specific biological conditions or therapeutic treatments. Pooled CRISPR screens enable genome-scale functional assessment, allowing researchers to identify genes essential for cell viability, drug resistance, synthetic lethality, and pathway-specific functions without prior assumptions about which genes may be important. The versatility of CRISPR screening platforms has revolutionized target discovery and validation in biomedical research, providing a direct functional link between genetic perturbations and phenotypic outcomes [10] [11].

Experimental Design and Platform Selection

CRISPR Screening Systems and Applications

Different CRISPR systems offer unique advantages depending on the experimental goals. The selection of an appropriate gene editing tool is fundamental to screen design and impacts the biological questions that can be addressed.

Table 1: Comparison of Major CRISPR Screening Approaches

| System | Mechanism | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRko (CRISPR knockout) | Cas9-induced DNA double-strand breaks lead to frameshift mutations via NHEJ repair [10] | Identification of essential genes, drug targets, and genes involved in viability/proliferation [10] [12] | Strong, complete loss-of-function signals; well-established analysis methods [10] |

| CRISPRi (CRISPR interference) | dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors (e.g., KRAB) blocks transcription [10] | Gene suppression studies, functional characterization of regulatory elements and lncRNAs [10] | Reversible knockdown; reduced off-target effects; tunable repression |

| CRISPRa (CRISPR activation) | dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., SAM system) enhances gene expression [10] | Gain-of-function studies, genetic suppressor screens, pathway activation [10] | Enables study of gene overexpression; identifies synthetic rescues |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of a CRISPR screen requires carefully selected reagents and materials that ensure efficient gene editing and phenotypic selection.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Library | Contains thousands of sgRNAs targeting genes of interest | Genome-wide (~20,000 genes) or focused libraries (specific pathways); 3-10 sgRNAs per gene recommended [11] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at DNA target sites | Can be delivered as plasmid, mRNA, or protein; stable cell lines expressing Cas9 preferred |

| Lentiviral Vector | Delivers sgRNA library into cells for stable integration | High-titer production (>10^8 IU/mL); includes selection markers (e.g., puromycin) [11] |

| Cell Lines | Models for studying biological questions | Appropriate disease models (e.g., iPSC-derived microglia [7]); validated Cas9 expression and sgRNA delivery efficiency |

| Positive Control sgRNA | Validates editing efficiency and workflow optimization | Targets known essential genes (e.g., TRAC, RELA in human cells) [13] |

| Negative Control sgRNA | Establishes baseline for non-specific effects | Scrambled sequence with no genomic targets; controls for cellular stress responses [13] |

Experimental Controls

Proper controls are essential for validating screening results and interpreting hits accurately. The following controls should be incorporated into every CRISPR screen:

- Positive Editing Controls: Use validated sgRNAs with known high editing efficiencies to target common genes (e.g., TRAC, RELA, CDC42BPB in human cells; ROSA26 in mouse models) to verify that transfection conditions are optimized [13].

- Negative Editing Controls: Include scramble sgRNAs that lack complementary genomic sequences, sgRNA-only (no Cas9), or Cas9-only (no sgRNA) controls to distinguish true phenotype from cellular stress responses to transfection [13].

- Mock Controls: Subject cells to transfection conditions without delivering any CRISPR components to establish baseline phenotypes unaffected by gene editing [13].

Detailed Protocol for Pooled CRISPR Knockout Screens

sgRNA Library Design and Construction

Designing efficient and specific gRNA is the critical first step for a successful CRISPR screen experiment. The process requires careful bioinformatic planning and molecular biology execution.

- sgRNA Design Principles: sgRNA targeting sequences (typically 18-23 bases) must be highly specific to avoid off-target effects while maintaining 40-60% GC content for optimal stability and binding efficiency. Bioinformatic tools like CRISPOR and CHOPCHOP help identify optimal sequences by scanning genomes for unique targeting sites with minimal off-target potential [11].

- Library Configuration: For genome-wide screens, libraries should include 3-10 sgRNAs per gene to ensure statistical robustness, with a minimum of 30x coverage to maintain library representation during amplification. Focused libraries targeting specific pathways or gene families reduce workload while increasing screening depth for particular biological processes [11].

- Vector Construction: sgRNA oligonucleotides are cloned into lentiviral vectors using high-fidelity cloning strategies, often employing negative selection markers (e.g., ccdB) to improve accuracy. The resulting library plasmids are amplified in E. coli, purified, and packaged into lentiviral particles using packaging cell lines (e.g., 293T cells) [11].

Cell Line Preparation and Library Delivery

- Cell Line Selection: Choose appropriate cell models that accurately represent the biological context being studied. For neurodegenerative disease research, specialized models like human iPSC-derived microglia (iMGL) can be employed [7]. Cells should demonstrate robust growth characteristics and susceptibility to viral infection.

- Library Transduction: Perform pilot transductions to determine the optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA. Use liposome transfection, electroporation, or viral infection methods optimized for your cell type. For difficult-to-transduce cells, consider specialized approaches like co-transduction with VPX virus-like particles (VPX-VLPs) to enhance lentiviral delivery [7].

- Selection and Expansion: Apply selection pressure (e.g., puromycin) 24-48 hours post-transduction to eliminate untransduced cells. Expand the library population for 5-7 cell doublings to allow for complete protein turnover and phenotypic manifestation before phenotypic assessment.

Phenotypic Selection Strategies

Different phenotypic selection methods enable the identification of genes involved in diverse biological processes.

- Dropout Screens: Monitor sgRNA abundance changes over time in proliferating cells without specific selection pressure. Depleted sgRNAs indicate essential genes required for cell viability or proliferation [10].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Use fluorescent reporters or antibodies to separate cells based on surface markers, intracellular signaling, or specific cell types. For example, a phagocytosis screen in iMGL can use pH-sensitive fluorescent probes to isolate cells with high vs. low phagocytic activity [10] [7].

- Drug Selection: Apply therapeutic compounds to identify genes involved in drug sensitivity or resistance. Genes whose targeting confers resistance will be enriched in surviving populations, while sensitizing genes will be depleted [12].

Bioinformatics Analysis of CRISPR Screen Data

Quality Control and Read Processing

Robust bioinformatics analysis is crucial for extracting meaningful biological insights from CRISPR screen data. The process begins with stringent quality control of the raw sequencing data.

- Sequencing Quality Assessment: Process raw FASTQ files to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads. Evaluate data quality using Q20 (>90%) and Q30 (>85%) thresholds. Data failing these standards should be re-sequenced [12]. Tools like ShortRead in R can subsample and assess read quality, nucleotide distribution, and quality scores across sequencing cycles [14].

- Read Alignment and Quantification: Align quality-filtered reads to the reference sgRNA library using aligners like Bowtie or Rsubread. Calculate sgRNA abundance from aligned reads (mapped reads), ensuring a minimum sequencing depth of 300x (mapped reads/number of sgRNAs) for statistical reliability [12].

Hit Identification and Statistical Analysis

Multiple analytical approaches have been developed to identify significantly enriched or depleted genes from CRISPR screen data.

- MAGeCK Algorithm: The Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout (MAGeCK) tool is specifically designed for CRISPR screen analysis. It uses a negative binomial distribution to model sgRNA abundance and a Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) algorithm to identify significantly enriched or depleted genes. The RRA algorithm scores and ranks each gene, with lower scores indicating higher confidence hits [10] [12].

- Statistical Thresholds: Identify candidate genes using a combination of statistical measures: p-value (< 0.05), false discovery rate (FDR < 0.05), and log fold change (LFC). While FDR < 0.05 provides the most stringent control, p-value < 0.01 combined with LFC ≤ -2 can effectively identify true positives while minimizing false negatives [12].

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Tools for CRISPR Screen Analysis

| Tool | Statistical Method | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAGeCK | Negative binomial distribution; Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) [10] | Comprehensive workflow; handles multiple sample comparisons; includes visualization [10] | Genome-scale knockout screens; essential gene identification |

| BAGEL | Reference gene set distribution; Bayes factor [10] | Bayesian approach; uses reference sets of essential/non-essential genes [10] | Essential gene identification with prior knowledge |

| PinAPL-Py | Negative binomial distribution; α-RRA, STARS [10] | Web-based interface; integrated analysis pipeline [10] | User-friendly analysis for non-bioinformaticians |

| CRISPRAnalyzeR | Multiple methods (DESeq2, MAGeCK, edgeR, etc.) [10] | Integrates eight different analysis approaches; web-based platform [10] | Comparative method evaluation; CRISPRi/CRISPRa screens |

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Following hit identification, functional annotation provides biological context to the candidate genes.

- Pathway Analysis: Perform Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to identify signaling pathways significantly overrepresented among hit genes, revealing biological processes affected by genetic perturbations [12].

- Gene Ontology Analysis: Conduct GO enrichment analysis to categorize hits into biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components, helping to prioritize genes based on functional relevance to the screened phenotype [12].

Applications in Target Discovery and Validation

Case Studies in Therapeutic Target Identification

CRISPR knockout screens have successfully identified novel therapeutic targets across diverse disease areas, demonstrating the power of this unbiased approach.

- Cancer Immunotherapy Targets: A genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screen identified the E3 ligase Cop1 as a key modulator of macrophage infiltration and a potential cancer immunotherapy target. Researchers used RRA algorithm ranking to prioritize Cop1 from the top hits, followed by functional validation demonstrating that Cop1 depletion enhanced antitumor immunity [12].

- Chemotherapy Synergistic Targets: A CRISPR screen in resistant small-cell lung cancer identified CDC7 as a synergistic target of chemotherapy. Researchers combined p-value (< 0.01) and LFC (≤ -2) criteria to identify CDC7, demonstrating that targeting CDC7 sensitized resistant cancer cells to conventional chemotherapy [12].

- Neurodegenerative Disease Mechanisms: A pooled FACS-based CRISPR knockout screening protocol in human iPSC-derived microglia (iMGL) enabled the identification of genetic drivers of neurodegenerative risk. This approach combined genetic risk loci from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with functional screening to pinpoint causal genes and pathways in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [7].

Hit Validation and Translation

Initial hit identification requires rigorous validation to confirm biological relevance and therapeutic potential.

- Multi-modal Validation: Candidate genes should be validated using orthogonal approaches including individual sgRNA validation, complementary assays (e.g., RNAi), and pharmacological inhibition where possible.

- Mechanistic Studies: Investigate the biological mechanisms underlying hit genes through downstream experiments assessing pathway modulation, protein expression changes, and phenotypic rescue.

- Therapeutic Assessment: Evaluate the therapeutic potential of targets using disease-relevant models, assessing efficacy, toxicity, and potential resistance mechanisms.

The integrated workflow from screening to validation provides a powerful pipeline for translating genetic discoveries into potential therapeutic strategies, accelerating the drug development process from target identification to preclinical assessment.

Functional genomic screening using CRISPR-Cas9 is a powerful methodology for unraveling gene function and identifying novel therapeutic targets at a systems level. The core principle involves creating genetic perturbations in a population of cells and observing subsequent phenotypic changes to draw causal inferences between genes and biological outcomes [15]. The two principal experimental formats for conducting these large-scale investigations are pooled screening and arrayed screening. The choice between these formats is foundational to experimental design, impacting everything from initial library selection to final data analysis [16]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these two approaches, outlining their respective protocols, advantages, and optimal applications within a drug discovery workflow.

Comparative Analysis: Pooled vs. Arrayed Screens

The decision to use a pooled or arrayed screen is multifaceted, hinging on the research question, available resources, and the biological model. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each format.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Pooled and Arrayed CRISPR Screens

| Feature | Pooled Screen | Arrayed Screen |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | A mixture of sgRNAs is delivered to a single population of cells [16] [15]. | Each sgRNA or gene target is delivered to cells in separate wells of a multiwell plate [17] [16]. |

| Library Delivery | Primarily lentiviral transduction for genomic integration [16] [15]. | Transfection or transduction; includes synthetic sgRNA complexed as RNP [17] [15]. |

| Phenotype Assay Compatibility | Binary assays only (e.g., cell viability, FACS sorting) [16] [15]. | Both binary and multiparametric assays (e.g., high-content imaging, morphology, secretion) [17] [16] [15]. |

| Genotype-Phenotype Linkage | Requires sequencing and bioinformatic deconvolution [16] [15]. | Directly linkable, as each well corresponds to one known genetic perturbation [17] [16]. |

| Typical Scale | Genome-wide (thousands of genes) [17]. | Targeted (dozens to hundreds of genes) [17]. |

| Primary Cell Compatibility | Low, requires cell proliferation and stable integration [16]. | High, works with non-dividing cells [16]. |

| Relative Cost | Lower upfront cost [16]. | Higher upfront cost [16]. |

| Data Analysis | Complex, requires NGS and specialized computational tools [10] [16]. | Simpler, often analogous to standard plate-based assays [16]. |

| Safety | Involves lentiviral vectors [17]. | Safer; allows for non-integrating RNP delivery [17]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Pooled CRISPR Knockout Screens

This protocol is adapted for a FACS-based phenotype but can be modified for viability selection [7] [16].

1. Library Construction and Validation

- sgRNA Library: Obtain a pooled sgRNA plasmid library as a glycerol stock. Amplify the library via PCR and validate its composition and uniformity by next-generation sequencing (NGS) [16].

- Lentiviral Production: Package the sgRNA plasmids into lentiviral particles. Purify and concentrate the virus [16].

- Titration: Determine the viral titer by transducing target cells and selecting with an antibiotic (e.g., puromycin). Use this to calculate the Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) [16].

2. Library Delivery and Cell Preparation

- Cell Line: Use a Cas9-expressing cell line or co-transduce with Cas9 [16].

- Transduction: Transduce the cell population at a low MOI (e.g., ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA. Include a non-transduced control [16].

- Selection: After 24-48 hours, apply antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) for 3-7 days to eliminate non-transduced cells and create a representation of the library [16]. Expand the selected cell population.

- Baseline Sample: Harvest a sample of cells representing the "T0" population before applying any phenotypic selection. Extract genomic DNA for NGS [16].

3. Phenotypic Selection and Analysis

- Apply Pressure: Subject the cell population to the experimental condition (e.g., drug treatment) or sort cells based on a marker using FACS [7] [16].

- Final Sample: Harvest the phenotypically selected cell population and extract genomic DNA.

- NGS and Bioinformatics: Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences from the T0 and final samples via PCR for NGS. Map the sequencing reads to the reference library to obtain sgRNA counts [16]. Use bioinformatics tools like MAGeCK to identify significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs, which point to genes affecting the phenotype [10].

Protocol for Arrayed CRISPR Knockout Screens

This protocol leverages ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for high-efficiency editing without viral integration [17].

1. Library Preparation

- sgRNA Format: Obtain an arrayed library as crRNAs or synthetic sgRNAs, often pre-dispensed in multiwell plates. For Cas9, complex crRNA with tracrRNA to form guide RNA [17].

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex the guide RNA with recombinant Cas9 protein to form RNP complexes in each well [17].

2. Cell Transfection and Incubation

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells expressing Cas9 or co-transfect with Cas9 into wells of a multiwell plate.

- Delivery: Transfect the RNP complexes into cells using a high-throughput method, such as electroporation (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector System) or lipid-based transfection [17].

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for a sufficient duration to allow for gene editing and phenotypic manifestation.

3. Phenotypic Assessment

- Assay Application: Apply the relevant assay to the plates. This can be a simple binary readout or a complex, high-content analysis measuring multiple parameters like morphology, protein aggregation, or secreted factors [17] [15].

- Data Collection: Use automated microscopy, plate readers, or other instrumentation to collect phenotypic data from each well.

- Data Analysis: Since each well corresponds to a single gene target, the analysis directly correlates the phenotype measured in a well with the specific gene knockout [17] [16]. No NGS deconvolution is required.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural and decision-making differences between the two screening formats.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a CRISPR screen requires careful selection of reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Screens

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Contains the guide RNA sequences that target genes of interest for knockout. | Designed for high on-target and low off-target activity. Available as pooled plasmid libraries or arrayed oligonucleotides [17] [16] [15]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | The enzyme that creates a double-strand break in the DNA at the site guided by the sgRNA. | Can be delivered via stable cell line, plasmid, or mRNA, or as a recombinant protein complexed with sgRNA as RNP [17] [15]. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Produces viral particles to deliver sgRNA constructs for stable genomic integration. | Essential for pooled screens. Requires careful titration of MOI [16] [15]. |

| Delivery Reagents | Facilitates the introduction of CRISPR components into cells. | For arrayed RNP screens, electroporation systems (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector) or lipid-based transfection reagents are used [17]. |

| Selection Agent (e.g., Puromycin) | Antibiotic for selecting successfully transduced cells in pooled screens. | Allows enrichment of cells that have integrated the sgRNA vector [16]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | For quantifying sgRNA abundance in pooled screens before and after selection. | Critical for the deconvolution step in pooled screening to identify hit genes [10] [16]. |

| Bioinformatics Software (e.g., MAGeCK) | Analyzes NGS data from pooled screens to rank genes based on sgRNA enrichment/depletion. | Uses statistical models to identify significant hits and control for false discoveries [10]. |

| High-Content Imaging System | Automatically captures and analyzes complex cellular phenotypes in arrayed screens. | Enables multiparametric readouts like cell morphology, protein localization, and more [16] [15]. |

| Ralinepag | Ralinepag, CAS:1187856-49-0, MF:C23H26ClNO5, MW:431.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2BAct | 2BAct, CAS:2143542-28-1, MF:C19H16ClF3N4O3, MW:440.8072 | Chemical Reagent |

Pooled and arrayed CRISPR screens are complementary tools in the functional genomics arsenal. Pooled screens offer a cost-effective method for genome-wideinterrogation with binary readouts, making them ideal for primary, discovery-phase research. In contrast, arrayed screens provide a versatile platform for targeted investigation of complex phenotypes in biologically relevant models, including non-dividing primary cells, and are perfectly suited for secondary validation and in-depth mechanistic studies [17] [16]. A strategic approach often involves using a pooled screen for initial, broad target identification, followed by an arrayed screen to validate hits and characterize their functional roles in a more physiologically relevant context [16] [15]. This combined workflow leverages the strengths of both formats to efficiently and rigorously advance therapeutic target discovery.

Executing a Successful Screen: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Library to Phenotype

In the realm of functional genomics, CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens have emerged as a powerful method for unbiased discovery of gene function. A critical first step in designing a robust screen is the selection of an appropriate single guide RNA (sgRNA) library. This choice, between comprehensive genome-wide libraries and more targeted focused libraries, fundamentally shapes the scope, cost, and feasibility of the entire research project. This application note provides a structured comparison of these two library types and details the experimental protocols for their use, framed within the broader context of establishing a standardized CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen pipeline.

The decision between a genome-wide and a focused sgRNA library hinges on the research objective, available resources, and the biological model system. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Genome-Wide vs. Focused sgRNA Libraries

| Feature | Genome-Wide Library | Focused Library |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Unbiased discovery of novel genes and pathways [18] [19] | Targeted investigation of a predefined gene set (e.g., kinases, transcription factors) [18] |

| Scope | Targets all protein-coding genes in the genome [18] [20] | Targets a specific subset of genes, based on prior knowledge (e.g., RNA-seq data) [18] |

| Library Size & Cost | Large (>75,000 sgRNAs); higher cost for reagents and sequencing [18] [21] | Small (a few hundred to thousands of sgRNAs); lower cost [18] |

| Throughput & Feasibility | Resource-intensive; may be challenging for complex models (e.g., organoids, in vivo) [21] | Higher throughput and feasibility for complex models with limited cell numbers [21] |

| Key Strength | Comprehensive; avoids pre-test selection bias [18] | Manageable and cost-effective; allows for deeper screening of a specific pathway [18] |

| Example Libraries | GeCKO, Brunello, Yusa v3 [22] [18] [21] | Custom-designed libraries for pathways like IL-17 signaling [18] |

Recent advancements have led to the development of optimized, minimal genome-wide libraries. These libraries use advanced algorithms to select highly effective sgRNAs, reducing the number of guides per gene without sacrificing performance. For instance, a 2025 benchmark study demonstrated that libraries with only 2-3 top-performing guides per gene could perform as well or better than larger historical libraries containing 6-10 guides per gene, offering significant cost and efficiency benefits [21].

A Decision Framework for Library Selection

The following workflow diagram outlines the key questions and decision points for selecting the most appropriate sgRNA library for a research project.

Experimental Protocol for a Pooled CRISPR Knockout Screen

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for performing a pooled screen using a lentiviral sgRNA library. The accompanying diagram visualizes the core workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pooled CRISPR Screens

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Pooled collection of guide RNAs for gene knockout. | GeCKO, Brunello, or custom libraries [22] [18] [20]. Available as plasmid DNA or ready-to-use lentiviral particles. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery system for stably integrating sgRNAs and Cas9 into the host cell genome. | Ensures single sgRNA integration per cell for clear genotype-phenotype linkage [22] [19]. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cell Line | A cell line that constitutively expresses the Cas9 nuclease. | Can be generated by transducing cells with a Cas9-lentivirus and selecting with antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) [18] [19]. Using a stable line ensures uniform Cas9 expression. |

| Selection Antibiotics | To select for cells successfully transduced with the viral constructs. | Puromycin for sgRNA vector selection; Blasticidin for Cas9 vector selection if using a dual-vector system [19] [20]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | For quantifying sgRNA abundance before and after screening to identify hits. | Essential for measuring enrichment/depletion of sgRNAs [22] [18] [19]. |

Pre-Screen Preparation

- sgRNA Library Reconstitution: If using a plasmid library, amplify it following a protocol designed to maintain library diversity, such as using extreme high-efficiency electrocompetent cells (e.g., Endura Duos) and ensuring colony counts are at least 1000-fold greater than the number of sgRNAs in the library [23].

- Cell Line Engineering: Generate a cell line that stably expresses Cas9. Transduce the target cells with a Cas9 lentiviral construct and select with the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., puromycin) for at least 7 days to create a homogeneous, Cas9-expressing population [19].

Screen Execution

- Lentivirus Production: Produce sgRNA library lentivirus by transfecting Lenti-X 293T cells with the sgRNA plasmid library and packaging plasmids. Collect virus-containing supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection [19].

- Cell Transduction: Transduce the Cas9-expressing cells at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI of 0.3-0.4) to ensure the majority of transduced cells receive only a single sgRNA. This is critical for directly linking a genotype to a phenotype [19]. After transduction, select cells with the appropriate antibiotic to eliminate non-transduced cells.

- Phenotypic Selection: Culture the transduced cell population under the selective pressure of interest (e.g., drug treatment, toxin, or simply cell growth for essential gene identification) for a sufficient duration (typically 10-14 days) to allow phenotypic manifestation [19].

- Harvest and Sequencing: Harvest genomic DNA from a population of at least 100 million cells to maintain sgRNA representation. Isolate the integrated sgRNA sequences via PCR and prepare them for next-generation sequencing (NGS) [22] [19].

Post-Screen Analysis

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use dedicated software (e.g., MAGeCK) to compare the abundance of each sgRNA in the selected population to its abundance in the baseline control population [21]. Genes are considered "hits" when targeted by multiple, independently enriched or depleted sgRNAs, increasing confidence in the result [18] [20].

- Hit Validation: Candidate genes must be validated using orthogonal methods. This typically involves transducing cells with individual sgRNAs targeting the candidate gene and confirming the phenotype in a low-throughput assay [22].

The strategic selection between genome-wide and focused sgRNA libraries is a cornerstone of successful CRISPR screening. Genome-wide libraries offer an unbiased path to discovery, while focused libraries provide a cost-effective and efficient means to probe specific biological hypotheses. By following the decision framework and detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can systematically design and execute CRISPR knockout screens to reliably identify genes critical to biological processes and therapeutic responses.

The advent of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 technology has revolutionized functional genomics, enabling systematic loss-of-function studies on a genome-wide scale [24]. A critical component enabling these large-scale screens is the lentiviral delivery system, which serves as the primary vehicle for introducing CRISPR components into target cells. Lentiviral vectors (LVVs) are preferred for their ability to efficiently transduce a broad range of cell types, including both dividing and non-dividing cells, and their capacity for stable genomic integration, ensuring persistent expression of CRISPR elements throughout cell divisions [24] [25].

This application note details the core principles and methodologies for designing and producing lentiviral vectors specifically optimized for CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens. We provide detailed protocols for vector system selection, library design, viral production, and quality control, framed within the context of genome-scale functional genomics research.

Vector System Design

The design of the vector system is a fundamental determinant of screening success, impacting viral titer, editing efficiency, and result consistency.

One-Vector vs. Two-Vector Systems

CRISPR-Cas9 lentiviral systems are configured as either one-vector or two-vector systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

| Feature | One-Vector System | Two-Vector System |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Cas9 and sgRNA on a single vector [26] | Cas9 and sgRNA on separate vectors [24] [27] |

| Lentiviral Titer | Lower, due to large provirus size (~8.2 kb) [27] | Higher, as each vector is smaller and packages efficiently [27] |

| Cas9 Expression | Variable across cells, leading to increased screening "noise" [27] | Consistent in pre-transduced cells, enabling uniform knockout efficiency [27] |

| Experimental Workflow | Simpler single transduction step [28] | Requires sequential transduction: Cas9 first, then sgRNA library [24] [27] |

| Ideal Use Case | Small-scale or single-gene knockout experiments [27] | Pooled genome-wide screens requiring high representation [24] [27] |

The two-vector system is generally recommended for genome-scale knockout screens. While the one-vector system simplifies experimental workflow, its poor viral packaging and heterogeneous Cas9 expression introduce significant bottlenecks and variability in large-scale screening contexts [27]. Pre-transducing cells with Cas9 to create a stable cell line ensures a uniform, high level of Cas9 protein, "setting the stage" for more rapid and reliable gene knockouts when the sgRNA library is introduced [27].

Key Vector Components and Design Considerations

Optimal vector design extends beyond the Cas9/sgRNA configuration. The following elements are critical for functionality and safety:

- Promoter Selection: The choice of promoter governs the expression levels of Cas9 and the sgRNA. Strong, ubiquitous promoters (e.g., EF1α, CMV) are often used for Cas9, while RNA Polymerase III promoters (e.g., U6) are standard for sgRNA expression [24] [29].

- Selection Markers: Antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., Puromycin, Blasticidin) are incorporated to enable selection of successfully transduced cells, ensuring a pure population for the screen [26] [28].

- Safety Features: Modern self-inactivating (SIN) designs, where enhancer and promoter elements in the 3' LTR are deleted, are essential to reduce the risk of insertional mutagenesis and improve vector safety [25] [29].

- Pseudotyping: The lentiviral envelope is commonly pseudotyped with the VSV-G protein, which confers a broad tropism, allowing the vector to infect a wide variety of human cell types [24] [25].

Diagram 1: Lentiviral Vector Design Overview. This chart outlines the core decisions and components involved in designing a lentiviral system for CRISPR screening, highlighting the trade-offs between one-vector and two-vector configurations.

sgRNA Library Design and Cloning

The quality of a genome-wide CRISPR screen is fundamentally dependent on the design of the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) library.

Design Principles for sgRNAs

Computational design of sgRNAs follows specific rules to maximize on-target efficiency and minimize off-target effects [24]:

- Target Location: sgRNAs are designed to target the 5' constitutive exons of protein-coding genes to maximize the probability of generating loss-of-function indels [26].

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): The target site must be immediately followed by a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence, which is essential for Cas9 recognition and cleavage [24].

- Specificity and Efficiency: Potential sgRNAs are analyzed for predicted on- and off-target activity. Guides with high GC content or homopolymer stretches are typically avoided. Nucleotide preferences at specific positions (e.g., a guanine at position 20 adjacent to the PAM) are also considered to enhance cutting efficiency [24].

- Multiplicity: To control for false positives and off-target effects, a minimum of 4-6 sgRNAs per gene are included in the library. This ensures that phenotypic effects can be attributed to the targeted gene rather than an individual sgRNA [24].

Library Cloning and Validation

Designed sgRNA oligonucleotide libraries are synthesized in a pooled format, amplified by PCR, and cloned en masse into the chosen lentiviral backbone[s] [24]. The resulting plasmid library is then transformed into bacteria, which are grown in a pooled culture to amplify the plasmid DNA. It is critical to verify the representation and integrity of the library at this stage through next-generation sequencing (NGS) to ensure that all sgRNAs are present at the expected frequencies without bias or dropout [24] [30].

Lentiviral Vector Production

The production of high-titer, functional lentiviral vectors is a multi-step process centered on the transient transfection of packaging cells.

Production Workflow

The standard method involves co-transfecting HEK293T cells (typically grown in a cell factory or bioreactor) with a set of plasmids using methods like PEI or calcium phosphate transfection [24] [31]. The required plasmids are:

- Transfer Plasmid(s): Contains the CRISPR cargo (e.g., the sgRNA library or Cas9).

- Packaging Plasmids: Provide the structural (Gag) and enzymatic (Pol) viral proteins in trans.

- Envelope Plasmid: Encodes the VSV-G protein, which pseudotypes the viral particle and determines host cell tropism [24].

Following transfection, the cell culture supernatant containing the viral particles is harvested, concentrated via ultracentrifugation or tangential flow filtration, and aliquoted for storage at -80°C [24].

Stable Producer Cell Lines as an Alternative

While transient transfection is the most common method for research-scale production, the development of stable producer cell lines is an advanced alternative that offers improved consistency and scalability. Recent approaches utilize transposase-mediated integration (e.g., using the piggyBac system) to stably integrate the necessary components into the cell genome. This method requires less DNA, accelerates cell line recovery, and generates highly diverse producer pools, leading to more consistent performance compared to traditional concatemeric-array integration methods [31].

Diagram 2: Lentiviral Vector Production Workflow. This diagram charts the key steps in lentiviral vector production, from plasmid transfection in HEK293T cells to the final quality-controlled, high-titer stock.

Critical Process Parameters and Quality Control

Consistent viral production requires careful monitoring of key parameters. The table below summarizes critical quality control (QC) metrics for the final lentiviral preparation.

| QC Parameter | Description | Typical Target/Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Titer | Measures infectious units per mL (IU/mL). Determines the volume of virus needed for transduction. | Determined by transducing target cells and quantifying transgene expression (e.g., by flow cytometry) or antibiotic resistance [25]. |

| Physical Titer | Quantifies total viral particles per mL (VP/mL), including non-infectious particles. | Measured by p24 ELISA or qPCR for viral RNA [25]. |

| Vector Copy Number (VCN) | The average number of viral integrations per cell genome. A critical safety attribute. | Clinical programs generally maintain VCN below 5 copies per cell [25]. Measured by ddPCR [25]. |

| Replication-Competent Lentivirus (RCL) | Tests for the presence of replication-competent virus, a critical safety test for clinical applications. | Absence confirmed in release testing [25]. |

| Endotoxin and Sterility | Ensures the viral preparation is free from microbial contamination. | Must pass standard pharmacopeial tests [25]. |

Application in CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Screens

With optimized lentiviral vectors in hand, researchers can proceed to perform the pooled CRISPR screen. The following protocol details the key steps from cell line preparation to hit analysis.

Protocol: Genome-Wide Knockout Screen with Pooled Lentiviral sgRNA Library

Objective: To identify genes essential for cell viability or involved in resistance to a therapeutic compound (e.g., Vemurafenib) through a pooled, loss-of-function genetic screen [26].

Materials:

- Target cells (e.g., A375 melanoma cell line [26] or iPSC-derived macrophages [28])

- High-titer lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., GeCKO, TKOv3 [24] [28])

- Stable Cas9-expressing cell line or Cas9-encoding lentivirus

- Polybrene (transduction enhancer)

- Puromycin or other appropriate selection antibiotic

- Reagents for genomic DNA extraction

- PCR reagents and primers for NGS library preparation

Method:

Cell Line Preparation:

- If using a two-vector system, generate a stable Cas9-expressing cell line by transducing the target cells with a Cas9 lentivirus, followed by antibiotic selection and expansion. Validate Cas9 activity before proceeding [27].

- For difficult-to-transduce cells like primary macrophages, pre-treatment with Vpx virus-like particles (Vpx-VLPs) is recommended to degrade the restriction factor SAMHD1 and significantly enhance transduction efficiency [28].

Library Transduction:

- Transduce the Cas9-expressing cells with the pooled lentiviral sgRNA library at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI of 0.3-0.6). This ensures most cells receive only one sgRNA, simplifying hit deconvolution [24] [26].

- To enhance infection, include polybrene (e.g., 8 µg/mL) and use spinfection (centrifugation at 800-1000 x g for 30-120 minutes at 32-37°C) [28].

- Ensure high library representation by using a cell population large enough so that each sgRNA is represented in at least 200-500 cells [24] [30].

Selection and Phenotypic Induction:

- Antibiotic Selection: 24-48 hours post-transduction, begin puromycin selection (e.g., 1-10 µg/mL, depending on cell line sensitivity) for 3-7 days to eliminate non-transduced cells [26] [28].

- Phenotypic Selection: After selection, split the population into experimental and control arms.

- For a negative selection screen (e.g., identifying essential genes), simply passage the cells for 14-21 days. sgRNAs targeting essential genes will be depleted over time [26].

- For a positive selection screen (e.g., drug resistance), treat the experimental arm with the selective agent (e.g., Vemurafenib for A375 cells) while maintaining the control arm in a vehicle. Resistant clones will enrich over 14-28 days [26].

Genomic DNA Extraction and NGS Library Preparation:

- Harvest a sufficient number of cells (from both selected and control populations) to maintain library representation.

- Extract genomic DNA.

- Perform a two-step PCR to amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences and add Illumina adapters for sequencing [24] [26]. The first PCR uses gene-specific primers, while the second adds barcodes and flow cell binding sites.

Sequencing and Hit Analysis:

- Sequence the PCR products on an Illumina platform to a depth that allows counting of each sgRNA.

- Quantify the relative abundance of each sgRNA in the experimental condition compared to the control.

- Use specialized algorithms (e.g., RIGER, MAGeCK) to identify genes for which multiple targeting sgRNAs are significantly enriched or depleted, ranking them as high-confidence "hits" [24] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|

| HEK293T/17 Cells | Standard cell line for high-titer lentiviral production due to high transfection efficiency and robust growth in suspension [24] [31]. |

| GeCKO Library | A genome-scale CRISPR Knock-Out library from the Zhang lab. Targets 18,080 human genes with 64,751 sgRNAs. Available from Addgene [24] [26]. |

| TKOv3 Library | Toronto KnockOut version 3 library targets 18,053 genes with 4 sgRNAs per gene. Optimized for screens where cell numbers are limiting [28]. |

| Brunello Library | A high-performance, second-generation human knockout library from the Doench and Root labs. Exhibits high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects (Addgene #73178) [24]. |

| Vpx Virus-Like Particles (Vpx-VLPs) | Essential for efficient transduction of restrictive immune cells like macrophages and dendritic cells. Degrades the host restriction factor SAMHD1 [28]. |

| LentiCRISPRv2 Vector | A widely used all-in-one lentiviral vector from the Zhang lab expressing Cas9, a sgRNA, and a puromycin resistance marker (Addgene #52961) [26] [28]. |

| Polybrene | A cationic polymer that reduces charge repulsion between viral particles and the cell membrane, enhancing transduction efficiency [28]. |

| VSV-G Envelope Plasmid | Plasmid encoding the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Glycoprotein (VSV-G) used for pseudotyping, which confers broad tropism to lentiviral vectors [24] [25]. |

| Acid-PEG9-NHS ester | Acid-PEG9-NHS ester, MF:C26H45NO15, MW:611.6 g/mol |

| Adh-503 | Adh-503, CAS:2055362-74-6, MF:C27H28N2O5S2, MW:524.7 g/mol |

The success of a CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen is fundamentally dependent on the efficiency and precision with which gene editing occurs in a cell population. Central to this is the choice of an appropriate cell model and the strategies employed for the stable expression of the Cas9 nuclease. Optimizing Cas9 expression and transduction is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant that influences the reliability of gene knockout, the uniformity of the edited cell pool, and the overall quality of the screening data. Within the broader context of developing a robust CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen protocol, this application note details key considerations and methodologies for establishing high-performance cellular systems for functional genetic screens.

Cas9 Expression Systems: Stable Cell Line Engineering

The foundation of a successful knockout screen is a cell line that consistently expresses the Cas9 nuclease. Two primary strategies for achieving this are through constitutive or inducible expression systems, each with distinct advantages.

Constitutive Cas9 Expression

In this approach, Cas9 is continually expressed in the cell line. A common method involves targeted knock-in of the Cas9 gene into a defined genomic locus to ensure stable expression and avoid gene silencing.

- Protocol: Generation of a Constitutive Cas9-EGFP iPSC Line

- Design: Select a genomic "safe harbor" locus, such as the GAPDH gene or the AAVS1 locus, for gene insertion to minimize disruption of native cellular functions.

- Vector Construction: Create a donor vector containing the Cas9-EGFP fusion gene flanked by homology arms (typically 500-800 bp) specific to the chosen locus. The construct should be driven by a strong, ubiquitous promoter (e.g., CAG, EF1α).

- Transfection: Co-transfect the donor vector and a plasmid expressing a guide RNA (gRNA) targeting the safe harbor locus into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using a high-efficiency method such as nucleofection.

- Selection and Cloning: Apply appropriate antibiotics selection post-transfection. Isolate single-cell clones and expand them.

- Validation: Genotype the clones using junction PCR to confirm precise integration. Verify Cas9-EGFP fusion protein expression and functionality through Western blotting and a surrogate editing assay. Confirm that the edited cell line retains pluripotency markers [32].

Inducible Cas9 Expression

Inducible systems provide temporal control over Cas9 expression, which is crucial for targeting essential genes and minimizing potential cytotoxicity or pre-screening adaptation. The doxycycline (Dox)-inducible system is widely used.

- Protocol: Creating a Dox-Inducible spCas9 hPSC Line (hPSCs-iCas9)

- System Integration: Insert the doxycycline-inducible spCas9-puromycin cassette into the AAVS1 (PPP1R12C) safe harbor locus to ensure stable and uniform expression.

- Vector Co-electroporation: Co-electroporate two plasmids at a 1:1 weight ratio: one carrying the Tet-On 3G system and the spCas9 cassette with AAVS1 homology arms, and another expressing Cas9 and a gRNA targeting the AAVS1 locus.

- Selection and Subcloning: At 48 hours post-nucleofection, select cells with 0.5 μg/mL puromycin for one week. Pick and expand surviving single-cell clones.

- Validation: Validate correct integration via junction PCR and confirm Cas9 protein expression via Western blot upon doxycycline induction. Assess the pluripotency of the established cell line through teratoma formation assays or immunostaining for pluripotency markers [33].

Table 1: Comparison of Constitutive and Inducible Cas9 Expression Systems

| Feature | Constitutive System | Inducible System (Dox) |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Activity | Continuous | Temporally controlled |

| Best For | High-throughput screens; non-essential gene targets | Studying essential genes; minimizing off-target effects & adaptation |

| Cytotoxicity Risk | Higher, due to constant Cas9 activity | Lower, as expression is brief and controlled |

| Experimental Complexity | Lower | Higher, requires optimization of inducer concentration/timing |

| Reported INDEL Efficiency | Varies; can be susceptible to silencing | 82-93% for single-gene knockouts after optimization [33] |

Optimizing Transduction and Gene Knockout Efficiency

Once a Cas9-expressing cell line is established, achieving high-efficiency gene knockout requires optimization of gRNA delivery and editing conditions.

Guide RNA (gRNA) Design and Delivery

The selection of an effective gRNA is paramount. In silico prediction tools can be used for initial screening, but experimental validation is necessary to identify ineffective gRNAs that may yield high INDEL rates but fail to ablate protein expression [33].

- gRNA Design and Synthesis Protocol:

- Selection: Use algorithms (e.g., Benchling, CCTop) to design gRNAs targeting early exons of the gene of interest, prioritizing those with high predicted on-target and low off-target scores.

- Synthesis: gRNAs can be produced by in vitro transcription (IVT-sgRNA) or chemical synthesis with stabilization modifications (CSM-sgRNA). Chemically synthesized sgRNAs with 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both ends demonstrate enhanced stability and editing efficiency [33].

- Validation: For critical targets, a rapid validation step is recommended. Transfert the gRNA into your Cas9-expressing cell line and use Western blotting to confirm loss of target protein, in addition to measuring INDEL frequency via sequencing.

Enhanced Knockout Efficiency via System Optimization

Systematic optimization of delivery parameters can dramatically increase knockout efficiency, especially in challenging cells like human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs).

- Key Parameters for Optimization [33]:

- Cell Health and Density: Ensure high cell viability pre-nucleofection and use an optimal cell density (e.g., 8x10^5 cells per nucleofection).

- sgRNA Amount: Titrate sgRNA amounts; 5 μg per reaction has been shown effective in optimized systems.

- Nucleofection Frequency: A repeated nucleofection 3 days after the first round can significantly boost INDEL rates.

- Cell-to-sgRNA Ratio: A higher ratio of cells to a fixed amount of sgRNA can improve editing efficiency.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of an Optimized Inducible Cas9 System in hPSCs

| Editing Target | Optimized Approach | Achieved Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Gene Knockout | Refined nucleofection parameters & sgRNA stability | 82% - 93% INDELs [33] |

| Double-Gene Knockout | Co-nucleofection with two sgRNAs at 1:1 ratio | >80% INDELs [33] |

| Large Fragment Deletion | Use of two sgRNAs targeting distant sites | Up to 37.5% homozygous deletion [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Screening

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Cell Line Generation

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AAVS1 Targeting System | Safe harbor locus for predictable transgene expression | Ensures consistent Cas9 expression and maintains cell health in hPSCs [33]. |

| Tet-On 3G System | Doxycycline-inducible gene expression | Allows temporal control of Cas9 for inducible knockout screens [33]. |

| Stable Cas9-EGFP iPSC Line | Constitutive Cas9 with fluorescent reporter | Facilitates tracking of Cas9-expressing cells and enables FACS sorting [32]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Enhanced nuclease guide RNA | 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications increase stability and editing efficiency [33]. |

| 4D-Nucleofector System | Physical delivery method | Enables high-efficiency RNP or nucleic acid delivery into hard-to-transfect cells like hPSCs [33]. |

| AF64394 | AF64394, MF:C21H20ClN5O, MW:393.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Afacifenacin | Afacifenacin|SMP-986|Muscarinic Antagonist | Afacifenacin (SMP-986) is a novel antimuscarinic agent researched for overactive bladder. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram outlines the logical process for selecting and implementing the optimal Cas9 expression strategy for a knockout screen.

The journey to a successful CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen begins with meticulous preparation of the cellular tool. The choice between constitutive and inducible Cas9 expression systems must be guided by the biological question and the nature of the target genes. As demonstrated, employing optimized protocols for cell line engineering, gRNA delivery, and knockout validation can consistently yield editing efficiencies exceeding 80%, creating a uniform and reliable foundation for your screen. By integrating these cell line considerations and optimization strategies, researchers can significantly enhance the precision and functional output of their CRISPR knockout screens, thereby generating more robust and biologically relevant data for drug discovery and functional genomics.

In a pooled CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen, a population of cells is perturbed by a library of guide RNAs (gRNAs) with the goal of linking specific genetic alterations to phenotypic outcomes. The reliability of this functional genomic exploration hinges on three critical experimental parameters: coverage, which ensures the library is adequately represented; the multiplicity of infection (MOI), which controls the number of genetic perturbations per cell; and selection parameters, which enable the enrichment of cells based on the phenotype of interest. Optimizing these factors is essential for minimizing noise, avoiding false positives and negatives, and generating statistically powerful, reproducible data [34] [18] [22]. This protocol details the methods for determining these key parameters, framed within the context of a genome-wide knockout screen.

Defining Critical Screening Parameters

The following parameters form the foundation of a well-executed screen. Their quantitative definitions and roles in screen quality are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Definitions and Calculations for Screening Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Role in Screen Quality | Calculation Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage | The number of cells representing each sgRNA in the library at the start of the screen [22]. | Ensures statistical power and reproducibility; mitigates stochastic dropout of sgRNAs. | Coverage = (Total Cells Transduced) / (Library Size) |

| Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) | The ratio of transducing viral particles to target cells [34] [35]. | Controls the fraction of cells receiving a single genetic perturbation, simplifying phenotype-genotype linkage. | MOI = (Transducing Units) / (Number of Cells) |

| Selection Pressure | The application of a biological challenge (e.g., drug, toxin) to enrich or deplete specific genotypes [18] [36]. | Enables the identification of genes involved in the phenotype of interest. | Determined empirically via kill curves (see Section 4.3). |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Protocol: Determining Multiplicity of Infection (MOI)

Purpose: To identify the viral titer that results in a low fraction of cells receiving multiple viral integrations, typically aiming for an MOI between 0.3 and 0.6 to ensure most transduced cells receive a single sgRNA [35] [36].

Materials:

- Cas9-expressing cell line of interest

- Packaged lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., from a commercial source like Addgene [18])

- Appropriate culture medium and selective antibiotic (e.g., puromycin)

- Multi-well plates

Method:

- Seed Cells: Plate a fixed number of cells (e.g., 1 x 10^5) in multiple wells of a multi-well plate.

- Viral Transduction: Infect the cells with a range of serial dilutions of the lentiviral library. Include an uninfected control well.

- Antibiotic Selection: 24 hours post-transduction, begin selection with the appropriate antibiotic. The minimum antibiotic concentration required should be predetermined by a kill curve on non-transduced cells [35].

- Calculate Functional Titer: After 3-7 days of selection, compare the number of viable cells in transduced wells to the uninfected control. The functional titer (in transducing units per mL, TU/mL) is calculated based on the dilution that results in 30-60% survival relative to the control. This point corresponds to an MOI of ~0.3-0.6 [35].