Functional Genomics Data Analysis Best Practices: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

This article provides a comprehensive guide to best practices in functional genomics data analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Functional Genomics Data Analysis Best Practices: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to best practices in functional genomics data analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the entire workflow, from foundational concepts and experimental design to advanced analytical methodologies, troubleshooting common challenges, and validating findings. By addressing key intents—establishing a strong foundation, applying robust methods, optimizing workflows, and ensuring rigorous validation—this guide empowers scientists to extract meaningful, reproducible biological insights from complex genomic datasets, thereby accelerating discovery in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Experimental Design for Robust Genomic Analysis

Defining Functional Genomics and its Key Data Types (RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq)

What is Functional Genomics? Functional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to describe gene and protein functions and interactions on a genome-wide scale [1]. Unlike traditional genetics which might focus on single genes, functional genomics uses high-throughput methods to understand the dynamic aspects of biological systems, including gene transcription, translation, regulation of gene expression, and protein-protein interactions [1] [2].

How does it support drug discovery? In pharmaceutical research, functional genomics helps identify and validate drug targets by uncovering genes and biological processes associated with diseases [3]. By using technologies like CRISPR to systematically probe gene functions, researchers can better select therapeutic targets, thereby improving the chances of clinical success [3].

Key Data Types in Functional Genomics

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq)

Description: RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) measures the quantity and sequences of RNA in a sample at a given moment, providing a comprehensive view of gene expression [1] [2]. It has largely replaced older technologies like microarrays and SAGE for transcriptome analysis [1].

Primary Applications:

- Gene Expression Profiling: Identifying which genes are active and their expression levels [4].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Comparing expression levels between different conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) [5].

- Single-Cell Analysis: Resolving gene expression heterogeneity within tissues [5] [6].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Description: ChIP-seq combines chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing to identify genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors and locations of histone modifications [7] [4]. It is a key assay for studying DNA-protein interactions and epigenetic regulation.

Primary Applications:

- Transcription Factor Binding Site Mapping: Finding where specific proteins interact with DNA [7].

- Histone Modification Profiling: Characterizing epigenetic marks that influence gene activity [7].

- Chromatin State Annotation: Defining functional regions of the genome (e.g., promoters, enhancers) [7].

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using Sequencing (ATAC-seq)

Description: ATAC-seq identifies regions of open chromatin by using a hyperactive Tn5 transposase to insert sequencing adapters into accessible DNA regions [8]. It is a rapid, sensitive method that requires far fewer cells than related techniques like DNase-seq or FAIRE-seq [8].

Primary Applications:

- Mapping Chromatin Accessibility: Genome-wide discovery of regulatory elements [8].

- Nucleosome Positioning: Identifying the placement and occupancy of nucleosomes [8].

- TF Footprinting: Inferring transcription factor binding at base-pair resolution [8].

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis

No single omics technique provides a complete picture. Integrating data from RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, and ATAC-seq is essential for constructing comprehensive models of gene regulatory networks [7] [4]. For instance, one can use ATAC-seq to find open chromatin regions, use ChIP-seq to validate the binding of a specific transcription factor in those regions, and use RNA-seq to link this binding to changes in the expression of nearby genes [4]. This multi-omics approach is a cornerstone of systems biology [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

ATAC-seq Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing nucleosome pattern in fragment size distribution [9] [8] | Over-tagmentation (over-digestion) of chromatin [9] | Optimize transposition reaction time and temperature. |

| Low TSS enrichment score (below 6) [9] | Poor signal-to-noise ratio; uneven fragmentation; low cell viability [9] | Check cell quality and ensure fresh nuclei preparation. |

| High mitochondrial read percentage [8] | Lack of chromatin packaging in mitochondria leads to excessive tagmentation [8] | Increase nuclei purification steps; bioinformatically filter out chrM reads. |

| Unstable or inconsistent peak calling [9] | Using a peak caller designed for sharp peaks (like MACS2 default) on broad open regions [9] | Try alternative peak callers like Genrich or HMMRATAC; ensure mitochondrial reads are removed before peak calling [9]. |

ChIP-seq & CUT&Tag Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sparse or uneven signal (common in CUT&Tag) [9] | Very low background can make regions with few reads appear as false positives [9] | Visually inspect peaks in a genome browser (IGV); merge replicates before peak calling to increase coverage [9]. |

| Poor replicate agreement [9] | Variable antibody efficiency, sample preparation, or PCR bias [9] | Standardize protocols; use high-quality, validated antibodies; check IP efficiency. |

| Peak caller gives inconsistent results [9] | Using narrow peak mode for broad histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3) [9] | Use a peak caller with a dedicated broad peak mode (e.g., MACS2 in --broad mode) [9]. |

| Weak signal in reChIP/Co-ChIP [9] | Inherently low yield from sequential immunoprecipitation [9] | Increase starting material; use stringent validation and manual inspection in IGV. |

General NGS Library Preparation Troubleshooting

| Problem | Failure Signal | Corrective Action [10] |

|---|---|---|

| Low Library Yield | Low final concentration; broad/shallow electropherogram peaks. | Re-purify input DNA/RNA to remove contaminants (e.g., salts, phenol); use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) instead of Nanodrop; titrate adapter:insert ratios. |

| Adapter Dimer Contamination | Sharp peak at ~70-90 bp in Bioanalyzer trace. | Optimize purification and size selection steps (e.g., adjust bead-to-sample ratio); reduce adapter concentration. |

| Over-amplification Artifacts | High duplicate rate; skewed fragment size distribution. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; use a high-fidelity polymerase. |

| High Background Noise | Low unique mapping rate; high reads in blacklisted regions. | Improve read trimming to remove adapters; use pre-alignment QC tools (FastQC) and post-alignment filtering (remove duplicates, blacklisted regions) [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main goal of functional genomics? A1: The primary goal is to understand the function of genes and proteins, and how all the components of a genome work together in biological processes. It aims to move beyond static DNA sequences to describe the dynamic properties of an organism at a systems level [1] [2].

Q2: When should I use ATAC-seq instead of ChIP-seq? A2: Use ATAC-seq when you want an unbiased, genome-wide map of all potentially active regulatory elements (open chromatin) without needing an antibody. Use ChIP-seq when you have a specific protein (transcription factor) or histone modification in mind and have a high-quality antibody for it [8].

Q3: My replicates show poor agreement in my ChIP-seq experiment. What should I do? A3: Poor replicate agreement often stems from technical variations in antibody efficiency, sample preparation, or sequencing depth. First, ensure your protocol is standardized. Then, check the IP efficiency and antibody quality. If the data is sparse, consider merging replicates before peak calling to improve signal-to-noise [9].

Q4: What are common pitfalls when integrating ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data? A4: A common mistake is naively assigning an open chromatin peak to the nearest gene, which ignores long-range interactions mediated by chromatin looping [9]. It's also important not to over-interpret gene activity scores derived from scATAC-seq data, as they are indirect proxies for expression and can be noisy [9].

Q5: What are chromatin states and how are they defined? A5: Chromatin states are recurring combinations of histone modifications that correspond to functional elements like promoters, enhancers, and transcribed regions. They are identified computationally by integrating multiple ChIP-seq data sets using tools like ChromHMM or Segway, which use hidden Markov models to segment the genome into states based on combinatorial marks [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | The core enzyme in ATAC-seq that simultaneously fragments and tags accessible DNA [8]. |

| Validated Antibodies | Critical for ChIP-seq and CUT&Tag to specifically target transcription factors or histone modifications [9]. |

| CRISPR gRNA Library | Enables genome-wide knockout or perturbation screens for functional gene validation [3]. |

| Size Selection Beads | Used in library cleanup to remove adapter dimers and select for the desired fragment size range [10]. |

| Cell Viability Stain | Essential for single-cell assays (scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq) to ensure high-quality input material [9]. |

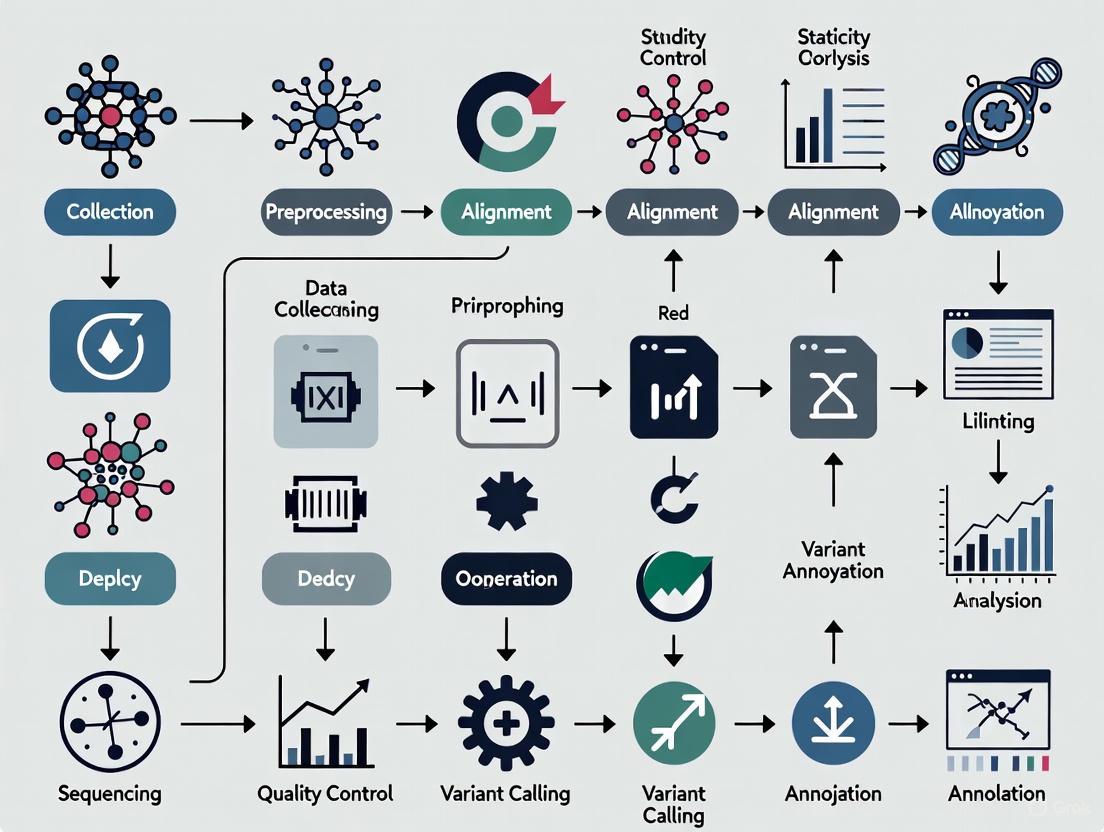

Experimental Workflow Visualization

A generalized workflow for a functional genomics study, from sample to insight, is shown below. This integrates elements from ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq analyses.

The Critical Role of Statistical Analysis in High-Dimensional Genomic Data

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Model Overfitting and Unreliable Feature Selection

Problem: My predictive model performs well on my dataset but fails when applied to new samples or independent datasets. Selected genomic features (e.g., genes, SNPs) change drastically with slight changes in the data.

Diagnosis: This typically indicates overfitting and failure to properly account for the feature selection process during validation. When the same data is used to both select features and validate performance, estimates become optimistically biased [11].

Solutions:

- Use Proper Validation Techniques: Employ resampling methods like bootstrapping or cross-validation that incorporate the entire feature selection process within each resample. This provides an unbiased estimate of model performance on new data [11].

- Apply Statistical Shrinkage: Use penalized regression methods (e.g., ridge regression, lasso, elastic net) that shrink coefficient estimates to avoid overfitting. Note that lasso, while producing sparse models, may exhibit instability in selected features [11].

- Ensure Adequate Sample Size: High-dimensional models are "data hungry." Some methods may require up to 200 events per candidate variable for stable performance in new samples [11].

Guide 2: Addressing Multiple Testing and False Discoveries

Problem: I am overwhelmed by the number of significant associations from my genome-wide analysis and cannot distinguish true signals from false positives.

Diagnosis: Conducting hundreds of thousands of statistical tests without correction guarantees numerous false positives due to multiple testing problems [11] [12].

Solutions:

- Go Beyond Simple Corrections: While False Discovery Rate (FDR) controls the proportion of false positives, it can be complemented with other approaches [11].

- Implement Ranking with Confidence Intervals: Instead of simple significance testing, rank features by association strength and use bootstrap resampling to compute confidence intervals for the ranks. This provides an honest assessment of feature importance and uncertainty, helping to avoid premature dismissal of potentially important features [11].

- Report Both False Discovery and Non-Discovery Rates: Focusing solely on false positives ignores the cost of false negatives (missing true biological signals). Consider and report both dimensions [11].

Guide 3: Correcting for Technical Biases in Multi-Platform Data

Problem: My integrated analysis of genomic data from different platforms (e.g., transcriptome and methylome) is dominated by technical artifacts and batch effects rather than biological signals.

Diagnosis: Technical biases from sample preparation, platform-specific artifacts, or batch effects can confound true biological patterns [13].

Solutions:

- Leverage Data Integration Methods: Use computational methods like MANCIE (Matrix Analysis and Normalization by Concordant Information Enhancement) designed for cross-platform normalization. MANCIE adjusts one data matrix (e.g., gene expression) using a matched matrix from another platform (e.g., chromatin accessibility) to enhance concordant biological information and reduce technical noise [13].

- Employ Robust Study Design: Randomize biospecimens across assay batches to avoid confounding batch effects with biological factors of interest. For case-control studies, balance cases and controls across batches [12].

- Validate with Biological Context: After correction, check if known biological patterns are enhanced. For example, after MANCIE correction, cell lines should cluster better by tissue type, and sequence motif analysis should reveal cell-type-specific transcription factors [13].

Guide 4: Choosing the Right Analytical Approach

Problem: I am unsure which statistical method to use for my high-dimensional genomic data, as many traditional methods are not applicable.

Diagnosis: Classical statistical methods designed for "large n, small p" scenarios break down in the "large p, small n" setting of genomics [12].

Solutions:

- Avoid One-at-a-Time (OaaT) Screening: OaaT testing (testing each feature individually against the outcome) is "demonstrably the worst approach" due to bias, false negatives, and ignorance of feature interactions [11].

- Select Methods Based on Your Goal:

- For Prediction: Use penalized regression (ridge, lasso, elastic net) or random forests. Be aware that random forests can suffer from poor calibration despite good discrimination [11].

- For Feature Discovery: Use multivariable modeling with bootstrap ranking instead of simple significance testing [11].

- For Data Exploration: Use dimension reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) before modeling [11].

- Consider Data Integration Frameworks: For multi-omics integration, tools like mixOmics in R provide a unified framework for exploration, selection, and prediction from combined datasets [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the single most common statistical mistake in high-dimensional genomic analysis? Answer: The most common mistake is "double dipping" - using the same dataset for both hypothesis generation (feature selection) and hypothesis testing (validation) without accounting for this selection process. This leads to optimistically biased results and non-reproducible findings [11].

FAQ 2: How much data do I actually need for a reliable high-dimensional genomic study? Answer: There is no universal rule, but traditional "events per variable" rules break down in high-dimensional settings. Studies are often underpowered, contributing to irreproducible results. Some evidence suggests that methods like random forests may require ~200 events per candidate variable for stable performance. Sample size planning should consider the complexity of both the biological question and the analytical method [12].

FAQ 3: My genomic data has many missing values. How should I handle this? Answer: Common approaches include:

- Deletion: Remove rows/columns exceeding a threshold of missingness (simplest but wasteful)

- Imputation: Replace missing values with zeros, mean/median values, or more sophisticated estimates

- The optimal approach depends on the mechanism of missingness and proportion of missing data [14]

FAQ 4: What is the difference between biological and technical replicates, and why does it matter? Answer: Biological replicates are measurements from different subjects/samples and are essential for making inferences about populations. Technical replicates are repeated measurements on the same subject/sample and help assess measurement variability. Confusing technical replicates with biological replicates is a fundamental flaw in study design, as technical replicates alone cannot support generalizable conclusions [12].

FAQ 5: How can I integrate genomic data from different sources (e.g., transcriptome and methylome)? Answer: Successful integration requires:

- Proper Data Matrix Design with consistent biological units (e.g., genes) across datasets

- Clear Biological Questions focused on description, selection, or prediction

- Tool Selection matched to your question (e.g., mixOmics for multiple analysis types)

- Data Preprocessing addressing missing values, outliers, normalization, and batch effects

- Preliminary Single-Dataset Analysis before integration [14]

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Differential Expression Analysis with RNA-Seq

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Implement best practices for bulk RNA-Seq studies, including adequate biological replication, randomization, and controlling for batch effects [15]

- Sequence Data Processing:

- Import FASTQ files and reference genomes

- Perform read quality control and diagnostics

- Trim reads to remove low-quality bases

- Map reads to reference genome

- Estimate read counts per gene [15]

- Statistical Analysis:

- Conduct diagnostic analyses on read counts

- Apply normalization procedures (e.g., DESeq2's median-of-ratios)

- Fit statistical models to test for differentially expressed genes

- Visualize results with heatmaps, volcano plots [15]

- Functional Interpretation:

- Perform gene set enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology and pathway annotations [15]

Protocol 2: Genomic Data Integration with mixOmics

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

- Data Matrix Design: Structure data with genes as biological units (rows) and genomic variables (expression, methylation, etc.) as columns [14]

- Question Formulation: Define clear objectives focused on:

- Description: Major interplay between variables (e.g., how DNA methylation affects expression)

- Selection: Identification of biomarker genes with specific patterns

- Prediction: Inferring genomic behaviors across individuals/species [14]

- Tool Selection: Choose mixOmics for its versatility in addressing all three question types using dimension reduction methods [14]

- Data Preprocessing:

- Handle missing values via deletion or imputation

- Identify and address outliers

- Apply appropriate normalization

- Correct for batch effects [14]

- Preliminary Analysis: Conduct separate analyses of each dataset before integration to understand data structure [14]

- Integration Execution: Apply multivariate methods (e.g., PCA, PLS) to reduce dimensionality and identify cross-dataset patterns [14]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Genomic Data Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Programming Environments | R Statistical Software | Data cleanup, processing, general statistical analysis, and visualization [16] |

| Genomics-Specific Packages | Bioconductor | Specialized tools for differential expression, gene set analysis, genomic interval operations [16] |

| Data Integration Platforms | mixOmics | Multi-omics data integration using dimension reduction methods for description, selection, and prediction [14] |

| Bias Correction Tools | MANCIE (Matrix Analysis and Normalization by Concordant Information Enhancement) | Cross-platform data normalization and bias correction by enhancing concordant information between datasets [13] |

| Sequencing Analysis Suites | Galaxy Platform, BaseSpace Sequence Hub | User-friendly interfaces for NGS data processing, quality control, and primary analysis [17] [15] |

| Differential Expression Packages | DESeq2 | Statistical analysis of RNA-Seq read counts for identifying differentially expressed genes [15] |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2 (R), Circos | Create publication-quality plots, genomic visualizations, heatmaps, and circos plots [16] |

Functional genomics data analysis enables genome- and epigenome-wide profiling, offering unprecedented biological insights into cellular heterogeneity and gene regulation [18]. However, researchers consistently face three interconnected challenges that can compromise data integrity and lead to misleading conclusions: the high dimensionality of data spaces where samples are defined by thousands of features, pervasive technical noise including batch effects and dropout events, and inherent biological variability [18] [19]. This technical support guide provides troubleshooting protocols and FAQs to help researchers identify, resolve, and prevent these issues within their experimental workflows, ensuring robust and reproducible biological findings.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Cell Type Identification and Clustering in scRNA-seq Data

Problem Description

After sequencing and initial analysis, cells that should form distinct clusters appear poorly separated, or known cell types cannot be identified. Batch effects obscure biological signals, hindering rare-cell-type detection and cross-dataset comparisons [18].

Diagnostic Steps

- Visual Inspection: Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP, t-SNE) coloring points by batch and suspected biological condition. If samples cluster primarily by processing date, sequencing lane, or other technical factors, batch effects are present [20].

- Quantitative Metrics: Calculate integration metrics:

Solutions

- Apply a Comprehensive Noise Reduction Tool: Use algorithms like iRECODE, which simultaneously reduces technical noise and batch effects by mapping data to an essential space and integrating correction, preserving full-dimensional data for downstream analysis [18].

- Leverage Procedural Batch-Effect Correction: For complex batch effects, employ methods like Harmony or the order-preserving method based on monotonic deep learning. These iteratively align cells across batches while preserving biological variation [18] [21].

- Experimental Design: For future studies, randomize samples across batches and ensure each biological condition is represented in every processing batch [20].

Issue 2: Technical Noise Obscuring Subtle Biological Signals

Problem Description

High-throughput data is dominated by technical artifacts, such as high sparsity ("dropout" events in scRNA-seq) or non-biological fluctuations, making it difficult to detect subtle but biologically important phenomena like tumor-suppressor events or transcription factor activities [18].

Diagnostic Steps

- Sparsity Analysis: Check the proportion of zero counts in your expression matrix. An unusually high rate suggests significant dropout [18].

- Variance Analysis: Examine the variance of housekeeping genes versus non-housekeeping genes. Effective noise reduction should diminish the variance of housekeeping genes (technical noise) while preserving or modulating the variance of other genes (biological signal) [18].

Solutions

- Utilize High-Dimensional Statistics: Apply tools like RECODE, which models technical noise from the entire data generation process as a probability distribution and reduces it using eigenvalue modification theory. This approach is effective across various single-cell modalities, including scRNA-seq, scHi-C, and spatial transcriptomics [18].

- Extend to Proteomics: For mass spectrometry-based proteomics, perform batch-effect correction at the protein level (e.g., using Ratio, Combat, or Harmony) after quantification, as this has been shown to be more robust than correction at the precursor or peptide level [22].

Issue 3: Loss of Biological Integrity During Data Integration

Problem Description

After batch correction or noise reduction, key biological relationships, such as inter-gene correlations or differential expression patterns, are lost or altered, leading to incorrect biological interpretations [21].

Diagnostic Steps

- Inter-gene Correlation: For a specific cell type, calculate the Spearman correlation coefficient for significantly correlated gene pairs before and after correction. A large deviation indicates loss of correlation structure [21].

- Order-Preserving Check: For a given gene, check if the relative ranking of expression levels across cells is maintained before versus after correction. This is crucial for preserving differential expression information [21].

Solutions

- Choose Order-Preserving Methods: Select batch-effect correction algorithms that inherently maintain the order of gene expression levels. The monotonic deep learning network-based method and ComBat have been shown to preserve these relationships better than methods that do not consider this feature [21].

- Validate with Biological Knowledge: Always check if known marker genes and pathways remain coherent and significant after correction. Use cross-validation with alternative methods (e.g., qPCR for RNA-seq) to confirm key findings [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Robust scRNA-seq Data Integration

This protocol details the steps for integrating multiple scRNA-seq datasets using a method that simultaneously addresses technical noise and batch effects.

- Input: Raw or normalized count matrices from multiple batches.

- Preprocessing and Quality Control:

- Filter cells based on mitochondrial content, number of features, and counts.

- Filter low-abundance genes.

- Normalize data using a method like SCTransform or log-normalization.

- Dual Noise Reduction with iRECODE:

- Map the gene expression data to an essential space using Noise Variance-Stabilizing Normalization (NVSN) and singular value decomposition.

- Integrate a batch-correction algorithm (e.g., Harmony) within this essential space to minimize computational cost and accuracy loss [18].

- Apply principal-component variance modification and elimination to reduce technical noise [18].

- Output: A denoised and batch-corrected full-dimensional gene expression matrix ready for downstream analysis (clustering, differential expression).

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow of the iRECODE algorithm for dual noise reduction.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Batch-Effect Correction Methods in Proteomics

This protocol is adapted from large-scale benchmarking studies to select the optimal batch-effect correction strategy for MS-based proteomics data [22].

- Input: Protein abundance matrices from multiple batches or labs.

- Experimental Design:

- Use reference materials (e.g., Quartet project materials) or a simulated dataset with known ground truth.

- Design two scenarios: one where sample groups are balanced across batches, and another where they are confounded.

- Apply Correction Strategies:

- Test corrections at different data levels: precursor, peptide, and protein.

- Apply multiple Batch-Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) such as Combat, Median Centering, Ratio, and Harmony.

- Performance Assessment:

- Feature-based: Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) within technical replicates.

- Sample-based: Compute Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) from PCA and use Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) to quantify contributions of biological vs. batch factors.

- Output Selection: Identify the most robust strategy (e.g., protein-level correction) and the best-performing BECA for your specific dataset.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between 'noise' and a 'batch effect' in my data?

- Noise refers to non-biological, stochastic fluctuations inherent to the technology, such as dropout events in scRNA-seq where some transcripts are not detected. Batch effects are systematic technical variations introduced when samples are processed in different groups (batches), such as on different days or by different technicians [18] [20]. Both can be mitigated with tools like RECODE and iRECODE [18].

Q2: Can batch correction accidentally remove true biological signal?

- Yes, overcorrection is a risk, particularly if batch effects are confounded with biological groups or if an inappropriate method is used [20]. To mitigate this, use methods designed to preserve biological variation (e.g., Harmony, order-preserving methods) and always validate results using known biological knowledge or independent experimental validation [21] [20].

Q3: For a new RNA-seq study, what is the minimum number of replicates needed to account for biological variability?

- While three replicates per condition is often considered a minimum standard, this is not universally sufficient. The required number depends on the expected effect size and the inherent biological variability within your system. For high variability, more replicates are necessary. Tools like

Scottycan help model power and estimate replicate needs during experimental design [24].

Q4: How do I choose between the many available batch correction methods?

- Selection should be based on your data type and needs. Consider the following comparison of popular methods:

| Method | Best For | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat [20] | Bulk RNA-seq, known batches | Empirical Bayes framework; effective for known, additive effects. | Requires known batch info; may not handle nonlinear effects well. |

| Harmony [18] [20] | scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics | Iteratively clusters cells to align batches; preserves biological variation. | Output is an embedding, not a corrected count matrix. |

| iRECODE [18] | Multi-modal single-cell data | Simultaneously reduces technical and batch noise; preserves full-dimensional data. | Higher computational load due to full-dimensional preservation. |

| Order-Preserving Method [21] | Maintaining gene rankings | Uses monotonic network to preserve original order of gene expression. | --- |

| Ratio [22] | MS-based Proteomics | Simple scaling using reference materials; robust in confounded designs. | Requires high-quality reference samples. |

Q5: My data is high-dimensional, but my sample size is small. What is the main pitfall?

- This scenario, known as the "curse of dimensionality," is a major challenge [19]. In high-dimensional spaces, distances between data points become less meaningful, and the risk of finding spurious correlations or clusters increases dramatically [19]. The key is to use methods rooted in high-dimensional statistics (like RECODE) and to avoid overfitting by using simple models and independent validation whenever possible [18] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table lists key computational tools and resources essential for addressing the major challenges discussed.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RECODE/iRECODE [18] | Dual technical and batch noise reduction | Single-cell omics (RNA-seq, Hi-C, spatial) |

| Harmony [18] [20] | Batch integration via iterative clustering | scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics |

| Monotonic Deep Learning Network [21] | Batch correction with order-preserving feature | scRNA-seq |

| FastQC [24] | Initial quality control of raw sequencing reads | RNA-seq |

| SAMtools [24] | Processing and QC of aligned reads | RNA-seq, variant calling |

| ComBat [20] [22] | Empirical Bayes batch adjustment | Bulk RNA-seq, Proteomics |

| Quartet Reference Materials [22] | Benchmarking and performance assessment | Proteomics, multi-omics studies |

| Trimmomatic/fastp [24] | Read trimming and adapter removal | RNA-seq |

| Lu AF21934 | Lu AF21934, MF:C14H16Cl2N2O2, MW:315.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Macimorelin Acetate | Macimorelin Acetate | Macimorelin acetate is a synthetic growth hormone secretagogue for diagnostic research of adult GH deficiency. This product is For Research Use Only. |

## Hardware Requirements for Bioinformatics Analysis

Selecting appropriate hardware is crucial for efficient bioinformatics analysis. Requirements vary significantly based on the specific analysis type and data scale.

Table: Recommended Hardware Specifications for Common Analysis Types

| Analysis Type | Recommended RAM | Recommended CPU | Storage | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General / Startup Laptop [25] | 16 GB | i7 Quad-core | 1 TB SSD | Suitable for scripting in Python/R and smaller analyses; use cloud services for larger tasks. |

| De Novo Assembly (Large Genomes) [25] [26] | 32 GB - Hundreds of GB | 8-core i7/Xeon or AMD Ryzen/Threadripper | 2-4 TB+ | Highly dependent on read number and genome complexity; PacBio HiFi assembly requires ≥32 GB RAM [26]. |

| Read Mapping (Human Genome) [26] | 16 GB - 32 GB | ~40 threads | 500 GB+ | Little speed gain expected beyond ~40 threads or >32 GB RAM [26]. |

| PEAKS Studio (Proteomics) [27] | 70 GB - 128 GB+ | 30+ - 60+ threads | As required | Requires a compatible NVIDIA GPU (CUDA compute capability ≥ 8, 8GB+ memory) for specific workflows like DeepNovo [27]. |

A successful functional genomics project relies on a curated toolkit of software and high-quality reference data.

### Key Software Tools and Platforms

- Programming Languages: R and Python are essential for data manipulation, statistical analysis, and custom scripting [28].

- Workflow Management Systems: Platforms like Nextflow, Snakemake, and Galaxy streamline pipeline execution, enhance reproducibility, and provide error logs for troubleshooting [29].

- Alignment & Mapping Tools: BWA and STAR are widely used for aligning sequencing reads to reference genomes [29].

- Variant Calling & Annotation: GATK and SAMtools are standard for identifying genetic variants [29].

- Data Quality Control: FastQC and MultiQC are critical for assessing the quality of raw sequencing data before analysis [29].

### Public Data Repositories

Public data repositories are invaluable for accessing pre-existing data to inform experimental design or for integration with self-generated data [28].

Table: Key Public Data Repositories for Functional Genomics

| Repository Name | Primary Data Types | URL / Link |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Gene expression, epigenetics, genome variation profiling | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ [28] |

| ENCODE | Epigenetics, gene expression, computational predictions | www.encodeproject.org [28] |

| ProteomeXchange (PRIDE) | Proteomics, protein expression, post-translational modifications | www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/ [28] |

| GTEx Portal | Gene expression, genome sequences (for eQTL studies) | www.gtexportal.org [28] |

| cBioPortal | Cancer genomics: gene copy numbers, expression, DNA methylation, clinical data | www.cbioportal.org [28] |

| Single Cell Expression Atlas | Single-cell gene expression (RNA-seq) | www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/sc [28] |

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

### Hardware and Setup

What is a reasonable hardware setup to get started with human genome analysis? A fast laptop with an i7 quad-core processor, 16 GB of RAM, and 1 TB of storage is a good starting point. For larger analyses like de novo assembly, which can require hundreds of gigabytes of RAM, you should plan to use institutional servers or cloud services [25].

Do I need a specialized Graphics Card (GPU) for bioinformatics? Most traditional bioinformatics tools do not require a powerful GPU. However, specific applications, particularly in proteomics like PEAKS Studio for its DeepNovo workflow, or machine learning tasks, do require a high-performance NVIDIA GPU with ample dedicated memory [27].

### Data and Analysis

Where can I find publicly available omics data to use in my research? There are many publicly available repositories. The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) is an excellent resource for processed gene expression data, while the ENCODE consortium provides high-quality multiomics data. For proteomics data, ProteomeXchange is the primary repository [28].

How can I ensure my bioinformatics pipeline is reproducible? Using workflow management systems like Nextflow or Snakemake is highly recommended. Additionally, always use version control systems like Git for your scripts and meticulously document the versions of all software and databases used [29].

### Troubleshooting Common Problems

My pipeline failed with a memory error. What should I do? This is common in memory-intensive tasks like assembly. First, check the log files to confirm the error. The solution is to rerun the analysis on a machine with more RAM. Always test pipelines on small datasets first to estimate resource needs [25] [26].

My analysis is taking an extremely long time to run. How can I speed it up? Check if the tools you are using can take advantage of multiple CPU cores. Ensure you have allocated sufficient threads. If computational resources are a bottleneck, consider migrating your analysis to a cloud computing platform which offers scalable computing power [29].

I am getting unexpected results from my pipeline. What are the first steps to debug this?

- Check Data Quality: Re-run quality control (e.g., with FastQC) on your raw input data.

- Isolate the Stage: Run the pipeline step-by-step to identify which component produces the anomalous output.

- Verify Tool Compatibility and Versions: Ensure all software dependencies are correctly installed and compatible.

- Consult Logs and Community: Scrutinize error logs and seek help from community forums specific to the tools you are using [29].

## Experimental Protocol: RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines a standard bulk RNA-Seq analysis workflow, from raw data to biological insight.

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

### Protocol Steps

Data Acquisition and Quality Control (QC)

- Input: Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format.

- Quality Control: Run FastQC on raw files to assess per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and other metrics. Use MultiQC to aggregate reports from multiple samples.

- Trimming/Filtering: Use tools like Trimmomatic to remove low-quality bases, adapters, and reads.

Alignment and Quantification

- Alignment: Map the trimmed high-quality reads to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner such as STAR or HISAT2.

- Quantification: Count the number of reads mapping to each gene using tools like FeatureCounts or HTSeq-count. This generates a count table for downstream analysis.

Differential Expression and Interpretation

- Differential Expression Analysis: Input the count table into statistical software packages in R (DESeq2, edgeR) to identify genes that are significantly differentially expressed between experimental conditions.

- Visualization and Enrichment: Create visualizations (e.g., PCA plots, volcano plots) and perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology, KEGG pathways) to interpret the biological meaning of the results.

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Resources for Functional Genomics Experiments

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | A curated, high-quality DNA sequence of a species used as a baseline for read alignment and variant calling [26]. |

| Gene Annotation (GTF/GFF) | A file containing the genomic coordinates of features like genes, exons, and transcripts, essential for quantifying gene expression [29]. |

| Raw Sequencing Data (FASTQ) | The primary output of sequencing instruments, containing the nucleotide sequences and their corresponding quality scores [29]. |

| Alignment File (BAM/SAM) | The binary (BAM) or text (SAM) file format that stores sequences aligned to a reference genome, the basis for many downstream analyses [29]. |

| Variant Call Format (VCF) | A standardized file format used to report genetic variants (e.g., SNPs, indels) identified relative to the reference genome [29]. |

| Mal-amido-PEG6-acid | Mal-amido-PEG6-acid, CAS:1334177-79-5, MF:C22H36N2O11, MW:504.5 g/mol |

| Mal-amido-PEG9-amine | Mal-amido-PEG9-amine, MF:C27H49N3O12, MW:607.7 g/mol |

In functional genomics research, the analysis of high-throughput sequencing data relies on a foundational understanding of key file formats. The FASTQ, BAM, and BED formats are integral to processes ranging from raw data storage to advanced variant calling and annotation [30]. This guide provides a technical overview, troubleshooting advice, and best practices for handling these essential data types, framed within the context of robust and reproducible data analysis protocols.

Understanding the Core Data Formats

FASTQ: The Raw Sequence Data Container

The FASTQ format stores the raw nucleotide sequences (reads) generated by sequencing instruments and their corresponding quality scores [30] [31]. It is the primary format for archival purposes and the starting point for most analysis pipelines.

Structure: Each sequence in a FASTQ file occupies four lines [31]:

- Sequence Identifier: Begins with an '@' symbol, followed by a unique ID and an optional description.

- The Raw Sequence: The string of nucleotide bases (e.g., A, C, G, T, N).

- A Separator: A '+' character, which may be followed by the same sequence ID (optional).

- Quality Scores: A string of ASCII characters representing the Phred-scaled quality score for each base in the raw sequence. The ENCODE consortium and modern Illumina pipelines use Phred+33 encoding [30].

Table: Breakdown of a FASTQ Record

| Line Number | Content Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | @SEQ_ID |

Sequence identifier line |

| 2 | GATTTGGGGTTCAAAGCAGTATCG... |

Raw sequence letters |

| 3 | + |

Separator line |

| 4 | !''*((((*+))%%%++)(%%%... |

Quality scores encoded in ASCII (Phred+33) |

Common Conventions:

- Paired-end Data: For paired-end experiments, the reads for each end are stored in two separate FASTQ files (often denoted

_1.fastqand_2.fastq), with the records in the same order [30]. - Unfiltered Data: FASTQ files from the ENCODE consortium are typically unfiltered, meaning they may still contain adapter sequences, barcodes, and spike-in reads, allowing users to apply their own trimming and filtering algorithms [30].

BAM: The Aligned Sequence Format

The Binary Alignment/Map (BAM) format is the compressed, binary representation of sequence alignments against a reference genome [30] [31]. It is the standard for storing and distributing aligned sequencing reads.

Structure: A BAM file contains a header section and an alignment section [31].

- Header: Includes critical metadata such as reference sequence names and lengths, the programs used for alignment, and the sequencing platform.

- Alignment Section: Each line represents a single read's alignment information, stored in a series of tab-delimited fields.

Table: Key Fields in a BAM/SAM Alignment Line

| Field Number | Name | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QNAME | r001 |

Query template (read) name |

| 2 | FLAG | 99 |

Bitwise flag encoding read properties (paired, mapped, etc.) |

| 3 | RNAME | ref |

Reference sequence name |

| 4 | POS | 7 |

1-based leftmost mapping position |

| 5 | MAPQ | 30 |

Mapping quality (Phred-scaled) |

| 6 | CIGAR | 8M2I4M1D3M |

Compact string describing alignment (Match, Insertion, Deletion) |

| 10 | SEQ | TTAGATAAAGGATACTG |

The raw sequence of the read |

| 11 | QUAL | * |

ASCII of Phred-scaled base quality+33 |

Key Features:

- Efficiency: The binary format is compact and enables efficient storage and processing of large datasets [31].

- Indexing: BAM files are accompanied by a BAI (BAM Index) file, which allows for rapid random access to reads aligned to specific genomic regions without reading the entire file [31].

- Comprehensive Data: ENCODE BAM files retain unmapped reads and spike-in sequences, with mapping parameters and processing steps documented in the file header [30].

BED: The Genomic Annotation Format

The BED (Browser Extensible Data) format describes genomic annotations and features, such as genes, exons, ChIP-seq peaks, or other regions of interest [30]. It is designed for efficient visualization in genome browsers like the UCSC Genome Browser.

Structure: A BED file consists of one line per feature, with a minimum of three required columns and up to twelve optional columns [32].

Table: Standard Columns in a BED File

| Column Number | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | chrom |

The name of the chromosome or scaffold |

| 2 | chromStart |

The zero-based starting position of the feature |

| 3 | chromEnd |

The one-based ending position of the feature |

| 4 | name |

An optional name for the feature (e.g., a gene name) |

| 5 | score |

An optional score between 0 and 1000 (e.g., confidence value) |

| 6 | strand |

The strand of the feature: '+' (plus), '-' (minus), or '.' (unknown) |

Usage Notes:

- The fourth column (

name) can contain various identifiers. In some contexts, such as a BED file converted from a BAM file, this column may contain the original read name [32]. - The BED format is closely related to the binary bigBed format, which is indexed for rapid display of large annotation sets in the UCSC Genome Browser [30].

The logical flow of data analysis from raw sequences to biological insights can be visualized as a workflow where these core formats are interconnected.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: I converted my BAM file to FASTQ, but the resulting file has very few sequences. What went wrong?

This is a known issue that can occur if the BAM file is not properly sorted before conversion [33]. For paired-end data, it is essential to sort the BAM file by read name (queryname) so that paired reads are grouped correctly in the output FASTQ files.

Solution:

- Use

samtoolsto sort your BAM file by queryname before conversion: - Use the sorted BAM file (

aln.qsort.bam) withbedtools bamtofastq, specifying both the-fqand-fq2options for the two output files [34]: Alternative: Thesamtools bam2fqcommand can also be a reliable alternative for this conversion [33].

Q2: What is the difference between the Phred quality score encoding in FASTQ files?

The Phred quality score can be encoded using two different ASCII offsets. The modern standard, used by the Sanger institute, Illumina pipeline 1.8+, and the ENCODE consortium, is Phred+33 [30]. This uses ASCII characters 33 to 126 to represent quality scores from 0 to 93. Be sure your downstream tools are configured for the correct encoding to avoid quality interpretation errors.

Q3: How can I quickly view the alignments for a specific genomic region from a large BAM file?

You can use the samtools view command in combination with the BAM index file (BAI). The BAI file provides random access to the BAM file, allowing you to extract reads from a specific region efficiently [31].

Solution:

- Ensure your BAM file is indexed. If not, create an index:

This will generate an

aln.bam.baifile. - Use

samtools viewto query the specific region (e.g., chr1:10,000-20,000):

Q4: My BED file from a pipeline has a read name in the fourth column. Is this standard?

While the BED format requires only three columns, the fourth column is an optional name field. In the context of a BED file derived directly from a BAM file (e.g., using a conversion tool), it is common for this field to contain the original read name from the BAM file [32]. This can be useful for tracking the provenance of a specific genomic feature back to the raw sequence read.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details key software tools and resources essential for working with FASTQ, BAM, and BED files in a functional genomics context.

Table: Essential Tools for Genomic Data Analysis

| Tool/Framework | Primary Function | Role in Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| bedtools [34] | Genome arithmetic | A versatile toolkit for comparing, intersecting, and manipulating genomic intervals in BED, BAM, and other formats. |

| SAMtools [30] [31] | SAM/BAM processing | A suite of utilities for viewing, sorting, indexing, and extracting data from SAM/BAM files. Critical for data management. |

| BWA [35] | Read alignment | A popular software package for mapping low-divergent sequencing reads to a large reference genome. |

| NVIDIA Clara Parabricks [35] | Accelerated analysis | A GPU-accelerated suite of tools that speeds up key genomics pipeline steps like alignment (fq2bam) and variant calling. |

| UCSC Genome Browser [30] | Data visualization | A web-based platform for visualizing and exploring genomic data alongside public annotation tracks. Supports BAM, bigBed, and BED. |

| Snakemake/Nextflow [5] | Workflow management | Frameworks for creating reproducible and scalable bioinformatics workflows, automating analyses from FASTQ to final results. |

| Mal-PEG2-acid | ||

| Mal-PEG2-NH-Boc | Mal-PEG2-NH-Boc, CAS:660843-21-0, MF:C15H24N2O6, MW:328.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Best Practices and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Converting a BAM File to Paired FASTQ Files

This protocol is essential for re-analyzing sequencing data or re-mapping reads with a different aligner [34].

- Input: A BAM file (

input.bam) containing paired-end reads. - Sort the BAM file by queryname. This ensures the paired reads are in the same order in the output FASTQ files.

- Convert the sorted BAM to FASTQ. Use

bedtools bamtofastqwith separate output files for each read end. - Output: Two FASTQ files:

read1.fq(end 1) andread2.fq(end 2).

Protocol: From FASTQ to BAM - A Basic Alignment Workflow

This core protocol outlines the key steps for generating a BAM file from raw FASTQ sequences [35].

- Input: Paired-end FASTQ files (

sample_1.fq.gz,sample_2.fq.gz) and a reference genome (reference.fa). - Align reads to the reference. Use an aligner like BWA.

The

-Rargument adds a read group header, which is critical for downstream analysis. - Convert SAM to BAM.

- Sort the BAM file by coordinate. This is required for many downstream tools and for indexing.

- Index the sorted BAM file. This creates the

.baiindex file for rapid access. - Output: A coordinate-sorted BAM file (

aligned.sorted.bam) and its index (aligned.sorted.bam.bai).

Best Practices for Data Integrity and Reproducibility

- Document Parameters: Always record the mapping algorithm and key parameters (e.g., mismatches allowed, handling of multi-mapping reads) in the header of your BAM files, as done by the ENCODE consortium [30].

- Use Containerization: Leverage technologies like Docker and Singularity to package your analysis workflows, ensuring consistency and reproducibility across computing environments [5].

- Adopt Workflow Managers: Use frameworks like Snakemake or Nextflow to create automated, scalable, and self-documenting pipelines from FASTQ processing to variant calling [5].

- Prioritize Data Security: When handling human genomic data, implement strict access controls and leverage encrypted cloud storage solutions that comply with regulations like HIPAA and GDPR [6] [36].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Data Submission and Access Issues

ProteomeXchange Submission Troubleshooting

ProteomeXchange provides a unified framework for mass spectrometry-based proteomics data submission, but researchers often encounter technical challenges during the process. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

Table 1: Common ProteomeXchange Submission Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solution | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large dataset transfer failures | Unstable internet connection; Firewall blocking ports; Aspera ports blocked by institutional IT [37] | Use Globus transfer service as an alternative to Aspera or FTP [37]; Break down very large datasets into smaller transfers | Generate the required submission.px file with metadata first, then use Globus for reliable large file transfers [37] |

| Resubmission process cumbersome | Need to resubmit entire dataset when modifying only a few files [37] | Use the new granular resubmission system in the ProteomeXchange submission tool to select specific files to update, delete, or add [37] | Ensure all files are correctly validated before initial submission |

| Dataset validation errors | Missing required metadata files; Incorrect file formats; Incomplete sample annotations | Use the automatic dataset validation process; Consult PRIDE submission guidelines and tutorials [37] | Follow PRIDE Archive data submission guidelines mandating MS raw files and processed results [37] |

| Private dataset access issues during review | Incorrect sharing links; Expired access credentials | Verify the private URL provided during submission; Contact PRIDE support if links expire [37] | Ensure accurate contact information is provided during submission for support communications |

Multi-Repository Data Integration Challenges

Integrating data across GEO, ENCODE, and ProteomeXchange presents unique technical hurdles due to differing metadata standards and data structures.

Table 2: Cross-Repository Data Integration Issues

| Integration Challenge | Impact on Research | Solution Approach | Tools/Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous data formats | Incompatible datasets that cannot be directly compared or combined | Implement FAIR data principles; Use PSI open standard formats (mzTab, mzIdentML, mzML) [37] | PSI standard formats [37]; SDRF-Proteomics format [37] |

| Metadata inconsistencies | Difficulty reproducing analyses; Batch effects in combined datasets | Use standardized ontologies (e.g., sample type, disease, organism) [37]; Implement SDRF-Proteomics format [37] | Ontology terms from established resources; Sample and Data Relationship File format [37] |

| Computational scalability issues | Inability to process combined datasets from multiple repositories | Utilize cloud-based platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure) with scalable infrastructure [5] [6] | AWS HealthOmics; Google Cloud Genomics; Illumina Connected Analytics [5] [6] |

| Cross-linking data references | Difficulty tracking related datasets across repositories | Use Universal Spectrum Identifiers (USI) for proteomics data [37]; Implement dataset version control | PRIDE USI service [37]; Dataset versioning pipelines |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Repository Selection and Data Access

Q: How do I choose between GEO, ENCODE, and ProteomeXchange for my data deposition needs?

A: The choice depends on your data type and research domain. ProteomeXchange specializes in mass spectrometry-based proteomics data and is the preferred repository for such data [37]. GEO primarily hosts functional genomics data including gene expression, epigenomics, and other array-based data. ENCODE focuses specifically on comprehensive annotation of functional elements in genomes. For multi-omics studies, you may need to deposit different data types across multiple repositories, then use integration platforms like Expression Atlas or Omics Discovery Index that aggregate information across resources [37].

Q: How can I access individual spectra from a ProteomeXchange dataset?

A: Use the PRIDE USI (Universal Spectrum Identifier) service available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/usi [38] [37]. This service provides direct access to specific mass spectra using standardized identifiers. Alternatively, you can browse ProteomeCentral to discover datasets of interest, then access the spectral data through the member repositories [38].

Q: What are the options for transferring very large datasets to ProteomeXchange?

A: ProteomeXchange currently supports three transfer protocols: Aspera (default for speed), FTP, and Globus [37]. For very large datasets or when facing institutional firewall restrictions that block Aspera ports, the Globus transfer service is recommended as it provides more reliable large-file transfers [37]. The ProteomeXchange submission tool generates the necessary submission.px file containing metadata, which can then be used with your preferred transfer method.

Data Submission and Management

Q: What are the mandatory file types for a ProteomeXchange submission?

A: PRIDE Archive submission guidelines require MS raw files and processed results (peptide/protein identification and quantification) [37]. Additional components may include peak list files, protein sequence databases, spectral libraries, scripts, and comprehensive metadata using controlled vocabularies and ontologies [37]. The specific requirements are aligned with ProteomeXchange consortium standards.

Q: How can I modify files in a private submission under manuscript review?

A: ProteomeXchange now offers a granular resubmission process [37]. Using the ProteomeXchange submission tool, select your existing private dataset and choose which specific files to update, delete, or add. The system only validates the new or modified files while maintaining dataset integrity, significantly simplifying the revision process compared to the previous requirement of resubmitting the entire dataset [37].

Q: How does ProteomeXchange support FAIR data principles?

A: As a Global Core Biodata Resource, ProteomeXchange implements multiple features supporting Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable data [37] [39]. These include: (1) Common accession numbers for all datasets; (2) Standardized data submission and dissemination pipelines; (3) Support for PSI open standard formats; (4) Programmatic access via RESTful APIs; (5) Integration with added-value resources like UniProt, Ensembl, and Expression Atlas for enhanced data reuse [37].

Data Analysis and Integration

Q: What computational resources are needed to analyze public data from these repositories?

A: Analyzing integrated datasets typically requires robust computational infrastructure. Options include:

- High-performance computing (HPC) clusters: For large-scale genomic data processing [40]

- Cloud platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure): Provide scalable storage and analysis capabilities, particularly beneficial for smaller labs [5] [6] [40]

- Containerized workflows: Using Docker or Singularity with workflow managers like Nextflow or Snakemake for reproducible analyses [5] The choice depends on dataset size, analysis complexity, and available institutional resources.

Q: How can I integrate proteomics data from ProteomeXchange with genomic data from ENCODE or GEO?

A: Successful multi-omics integration requires:

- Data harmonization: Convert diverse data types into compatible formats using standards like mzTab for proteomics [37]

- Metadata alignment: Map sample identifiers across datasets and ensure consistent experimental condition annotations [37] [40]

- Computational frameworks: Utilize tools that support multi-omics data integration, such as those incorporating machine learning for pattern recognition across data layers [5] [40]

- Cross-referencing: Leverage resources like Expression Atlas that already integrate proteomics data with other omics data types [37]

Experimental Protocols for Data Repository Workflows

Standard ProteomeXchange Data Submission Protocol

This protocol outlines the step-by-step process for submitting mass spectrometry-based proteomics data to ProteomeXchange repositories, specifically through the PRIDE Archive.

Materials Required:

- Mass spectrometry raw files (vendor formats or converted to mzML)

- Processed identification/quantification results

- Sample metadata annotations

- Protein sequence databases or spectral libraries used for searching

- Computational environment with internet access and file transfer capability

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Pre-submission Preparation

- Gather all raw mass spectrometry files from your experiment

- Compile processed results from search engines (e.g., MaxQuant, ProteomeDiscoverer)

- Organize sample metadata using controlled vocabularies (species, tissues, cell types, diseases) [37]

- Ensure compliance with data quality standards for your mass spectrometer platform

Metadata Assembly

- Download the ProteomeXchange submission tool

- Input experiment details: title, description, sample annotations

- Select appropriate ontology terms for experimental factors

- Define sample-data relationships using SDRF-Proteomics format when applicable [37]

File Transfer and Validation

- Select transfer protocol: Aspera (default), FTP, or Globus (for large datasets) [37]

- Upload files to the PRIDE Archive system

- Run automatic validation checks to identify formatting or completeness issues

- Address any validation errors identified by the system

Submission Finalization

- Complete the submission process to receive a PXD identifier

- Private dataset URL will be provided for manuscript review purposes

- Dataset becomes public upon manuscript publication or after specified embargo period

Post-Submission Management

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For large dataset transfers (>100GB), use Globus to avoid connection timeouts [37]

- If submission tool freezes during transfer, restart and use alternative transfer protocol

- For resubmissions, use the granular system to modify only necessary files rather than entire datasets [37]

Cross-Repository Data Integration Protocol

This protocol enables researchers to integrate proteomics data from ProteomeXchange with genomic data from ENCODE or GEO for multi-omics analysis.

Data Integration Workflow

Materials Required:

- Dataset accessions from ProteomeXchange (PXD IDs), GEO (GSE IDs), and/or ENCODE

- Computational environment with R/Python and necessary packages

- Cloud computing or HPC access for large-scale data integration

- Containerization platform (Docker/Singularity) for reproducibility

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Retrieval

- Download proteomics data from ProteomeXchange via PRIDE API or FTP

- Retrieve corresponding genomics data from GEO or ENCODE using their access APIs

- Extract metadata and sample information from all sources

Data Harmonization

- Convert all data to standardized formats (e.g., mzTab for proteomics [37])

- Normalize quantitative measurements across platforms

- Apply quality control filters specific to each data type

- Resolve batch effects using statistical methods

Sample Matching

- Align sample identifiers across datasets

- Verify biological and technical replicates match appropriately

- Resolve inconsistencies in experimental condition annotations

Integrated Analysis

Visualization and Interpretation

- Generate multi-omics visualizations (heatmaps, network diagrams)

- Create unified pathway diagrams showing multi-layer regulation

- Interpret findings in biological context

- Validate using independent datasets or experimental approaches

Quality Control Measures:

- Verify sample matching accuracy through technical metadata

- Assess data quality using platform-specific metrics

- Validate integration through known relationships between omics layers

- Perform sensitivity analyses to ensure robust findings

Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics Data Analysis

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Repository Data Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workflow Management | Nextflow, Snakemake, Cromwell [5] | Create reproducible, scalable analysis pipelines | Processing large-scale datasets from multiple repositories; Ensuring analysis reproducibility |

| Containerization | Docker, Singularity [5] | Package software and dependencies for portability | Maintaining consistent analysis environments across different computing platforms |

| Cloud Platforms | AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure [5] [6] | Provide scalable computational infrastructure | Handling terabyte-scale datasets from public repositories; Multi-institutional collaborations |

| Proteomics Data Processing | ProteomeXchange submission tool, PRIDE APIs [37] | Handle proteomics data submission and retrieval | Accessing and analyzing PRIDE datasets; Submitting new datasets to ProteomeXchange |

| Multi-Omics Integration | EpiMix, MEME, Cytoscape [40] | Integrate and visualize diverse data types | Combining proteomics, genomics, and epigenomics data from multiple repositories |

| AI/ML Tools | DeepVariant, DeepBind, Seurat [5] [40] | Apply machine learning to genomic data analysis | Variant calling; Transcription factor binding prediction; Single-cell data analysis |

| Specialized Algorithms | Minimap2, STAR, HISAT2, Bowtie2 [40] | Process specific data types (long-read, RNA-seq, etc.) | Handling diverse sequencing technologies represented in public repositories |

From Data to Discovery: Essential Processing, Analytical Methods, and Tools

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges encountered during the quality control (QC) and preprocessing of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data, providing solutions based on established best practices.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My FastQC report shows "Failed" for "Per base sequence quality". What should I do? A failed status for per-base sequence quality, typically indicated by low Phred scores in the later cycles of your reads, suggests a loss of sequencing quality over the course of the run. This is common and can be addressed through pre-processing:

- Trim Low-Quality Bases: Use trimming tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases from the 3' end of reads. This prevents inaccurate base calls from affecting downstream analyses like variant calling or read alignment [41] [42].

- Set Appropriate Thresholds: The specific quality threshold for trimming can be determined from the FastQC report itself. A common practice is to use a sliding window that trims once the average quality falls below a Phred score of 20 (indicating a 1% error rate) [41].

Q2: How can I check if my sequencing data is contaminated? Contamination from exogenous sources (e.g., host DNA, laboratory reagents, or the PhiX control phage) can be detected using several methods [43]:

- Metagenomic Classification: Tools like Kraken2 or Centrifuge can classify all reads in your sample against a comprehensive database, quickly identifying reads that do not belong to your target organism [43].

- Reference-Based Mapping: Map your reads to the suspected contaminant genome (e.g., human, PhiX) using aligners like BWA or Bowtie. Reads that map successfully to these references should be removed from your dataset [43].

- Kmer-Based Comparison: Tools like Mash can calculate a distance measure between your sequence data and a reference genome, providing a fast way to check for large-scale contamination [43].

Q3: What is adapter contamination and how is it removed? Adapter contamination occurs when the synthetic oligonucleotides used during library preparation remain attached to your sequence reads. This can hinder alignment as these sequences do not exist in the biological genome [41].

- Detection: FastQC can often detect the presence of overrepresented adapter sequences in your data [42].

- Removal: Tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic are designed to identify and trim these adapter sequences from the ends of your reads [41] [42]. PathoQC integrates this functionality seamlessly into its workflow [42].

Q4: I have a single-cell RNA-seq dataset. How is QC different? For single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), quality control focuses on cell-level metrics to distinguish high-quality cells from empty droplets or dead/dying cells. This is performed by calculating QC covariates for each cell barcode [44]:

- Number of Counts per Barcode (Count Depth): Low total counts may indicate an empty droplet.

- Number of Genes per Barcode: Cells with very few detected genes are likely to be low-quality.

- Fraction of Mitochondrial Counts per Barcode: A high percentage suggests a dying cell with broken cytoplasmic membrane, releasing cytoplasmic mRNA. Mitochondrial genes are often identified by a prefix such as "MT-" in humans or "mt-" in mice [44].

- Filtering: Cells that are outliers for these metrics (e.g., using Median Absolute Deviations (MAD)) are typically filtered out [44].

Common Problems and Solutions Table

The following table summarizes specific QC failures, their potential causes, and recommended actions.

| Problem | Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution [41] [45] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapter Contamination | FastQC reports overrepresented adapter sequences; poor alignment rates. | Incomplete adapter removal during library prep. | Trim adapters with tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic. |

| Low-Quality Reads | Per-base sequence quality fails in FastQC; low Phred scores. | Degradation of sequencing quality over cycles. | Trim low-quality bases from read ends using quality trimming tools. |

| Sequence Contamination | Reads map to unexpected genomes (e.g., PhiX, E. coli, human). | Laboratory or reagent contamination during sample prep. | Identify and remove contaminant reads using Kraken2 or by mapping to contaminant genomes. |

| Failed QC Metric | A single QC rule (e.g., 12s) is violated. | Random statistical fluctuation or early warning of a systematic issue. | Avoid simply repeating the test. Investigate the root cause using a systematic approach, checking calibration, reagents, and instrumentation [45]. |

| Low Library Complexity | High levels of PCR duplication; few unique reads. | Over-amplification during PCR, or low input material. | Filter duplicate reads; optimize library preparation protocol. |

Experimental Protocols for Key QC Experiments

Protocol 1: Comprehensive QC for Bulk RNA-Seq or WGS Data

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for quality control and preprocessing of bulk sequencing data, such as from RNA-Seq or Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) experiments [43] [41] [42].

1. Assess Raw Data Quality with FastQC and MultiQC

- Objective: Generate a comprehensive report on raw sequence data quality.

- Methodology:

- Run FastQC on your raw FASTQ files. This tool provides information on read length, quality scores along reads, GC content, adapter contamination, and more [43] [41].

- For multiple samples, use MultiQC to aggregate all FastQC reports into a single, interactive summary for efficient comparative assessment [43].

2. Remove Adapters and Trim Low-Quality Bases

- Objective: Eliminate technical sequences and low-confidence bases.

- Methodology:

- Use Cutadapt to search for and remove known adapter sequences. It performs an end-space free alignment to identify and trim these artifacts [42].

- Use a trimming tool (e.g., the one within Trimmomatic or Cutadapt) to remove low-quality bases from the 3' end of reads. A common strategy is sliding-window trimming [41].

3. Remove Contaminating Sequences

- Objective: Identify and exclude reads originating from contaminants.

- Methodology:

- Metagenomic Classification: Use Kraken2 or Centrifuge to taxonomically classify all reads against a database. Any read classified to an unexpected organism (e.g., PhiX, microbial species) can be filtered out [43].

- Alignment-Based Removal: Align reads to a database of known contaminant genomes (e.g., human, PhiX) using a fast aligner. Reads that map are considered contaminants and are removed from subsequent analysis [43].

4. (Optional) Filter Low-Quality Reads

- Objective: Remove entire reads that are too short or of overall poor quality after trimming.

- Methodology:

- Tools like PRINSEQ (integrated into PathoQC) can filter reads based on parameters such as minimum length, mean quality score, and complexity [42].

Protocol 2: Quality Control for Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

This protocol details the unique QC steps required for scRNA-seq data, starting from a count matrix [44].

1. Calculate QC Metrics

- Objective: Compute cell-level metrics to distinguish high-quality cells.

- Methodology:

- Using a tool like Scanpy in Python, calculate the following key metrics for each cell barcode [44]:

total_counts: Total number of UMIs/molecules (library size).n_genes_by_counts: Number of genes with at least one count.pct_counts_mt: Percentage of total counts that map to mitochondrial genes.

- Mitochondrial genes are identified by a prefix (e.g., "MT-" for human, "mt-" for mouse). Ribosomal and hemoglobin genes can also be flagged [44].

- Using a tool like Scanpy in Python, calculate the following key metrics for each cell barcode [44]:

2. Filter Out Low-Quality Cells

- Objective: Remove barcodes that likely represent empty droplets or dead cells.

- Methodology:

- Automatic Thresholding: Use a robust statistical method like Median Absolute Deviation (MAD). A common practice is to filter out cells that are more than 5 MADs away from the median for any of the key QC metrics [44].

- Manual Thresholding: Based on visual inspection of the distributions (violin plots, scatter plots) of the QC metrics. For example, one might remove cells with a mitochondrial count percentage above 20% [44].

Protocol 3: Quality Control for Functional Genomics (e.g., ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq)

This protocol covers assay-specific QC for techniques where signal is concentrated in specific genomic regions [46].

1. Assess Enrichment with Cumulative Fingerprint

- Objective: Determine how well the signal can be differentiated from background noise.

- Methodology:

- Use the

plotFingerprintcommand from deepTools on your processed BAM files. - The tool samples the genome, counts reads in bins, sorts the counts, and plots the cumulative sums. A good quality sample with sharp, enriched peaks will show a steep curve, while a poor sample will have a flatter curve closer to the background [46].

- Use the

2. Evaluate Replicate Concordance

- Objective: Assess the overall similarity between biological replicates.

- Methodology:

- Use

multiBamSummary binsfrom deepTools to count reads in genomic bins across all samples. - Then, use

plotCorrelationto generate a heatmap of Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients between the samples. High correlations between replicates indicate good reproducibility [46].

- Use

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key software tools and their functions for establishing a robust NGS QC and preprocessing pipeline.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Application / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC [43] [41] | Quality metric assessment for raw FASTQ data. | Provides an initial health check of sequencing data before any processing. |

| MultiQC [43] | Aggregates results from multiple tools (FastQC, etc.) into a single report. | Essential for reviewing results from large, multi-sample projects. |

| Cutadapt [41] [42] | Finds and trims adapter sequences and other tag sequences from reads. | Crucial for preventing adapter contamination from affecting alignment. |

| Trimmomatic [41] | A flexible tool for trimming adapters and low-quality bases. | Popular for its sliding-window trimming approach and efficiency. |

| Kraken2 [43] | Metagenomic sequence classifier. | Rapidly identifies the taxonomic origin of reads to detect contamination. |

| PathoQC [42] | Integrated, parallelized QC workflow. | Combines FastQC, Cutadapt, and PRINSEQ into a single, efficient pipeline. |

| Scanpy [44] | Python toolkit for single-cell data analysis. | Used for calculating and visualizing scRNA-seq-specific QC metrics. |

| deepTools [46] | Suite of tools for functional genomics data. | Used for QC methods like cumulative enrichment and replicate clustering. |

| DRAGEN [47] | Comprehensive secondary analysis platform. | Provides ultra-rapid, end-to-end pipelines for WGS, RNA-seq, etc., including QC. |

| Mal-PEG2-NHS ester | Mal-PEG2-NHS ester, CAS:1433997-01-3, MF:C15H18N2O8, MW:354.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mal-PEG3-NHS ester | Mal-PEG3-NHS ester, MF:C17H22N2O9, MW:398.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |