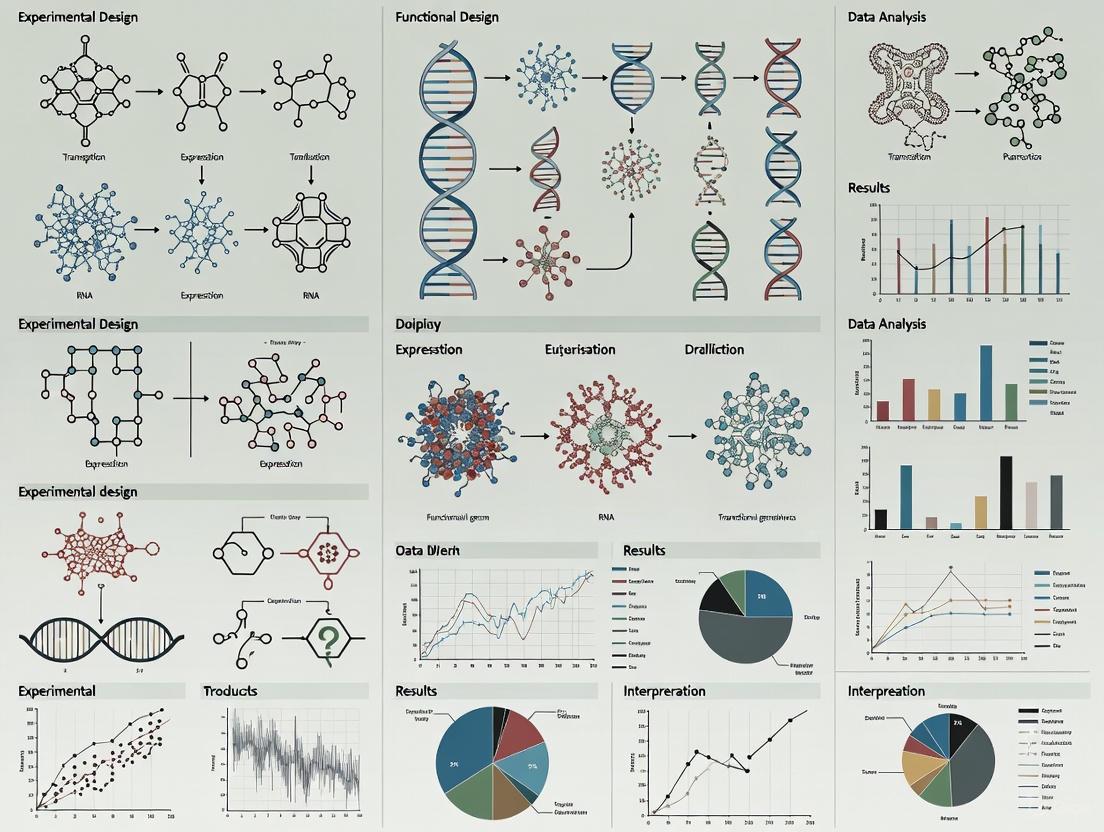

Functional Genomics Research Tools and Experimental Design: A Comprehensive Guide for Scientists

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the functional genomics landscape.

Functional Genomics Research Tools and Experimental Design: A Comprehensive Guide for Scientists

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the functional genomics landscape. It covers foundational concepts and the goals of understanding gene function and interactions, details the core technologies from CRISPR to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and their applications in drug discovery and disease modeling, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for complex systems and data analysis, and offers frameworks for validating findings and comparing the strengths of different methodological approaches. The integration of artificial intelligence and multi-omics data is highlighted as a key trend shaping the future of the field.

Understanding Functional Genomics: From Gene Sequence to Biological Function

Functional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to describe gene and protein functions and interactions, moving beyond the static information of DNA sequences to focus on the dynamic aspects such as gene transcription, translation, and regulation [1] [2]. It leverages high-throughput, genome-wide approaches to understand the relationship between genotype and phenotype, ultimately aiming to provide a complete picture of how the genome specifies the functions and dynamic properties of an organism [1] [3].

This guide explores the core techniques, applications, and experimental protocols that define modern functional genomics research, with a focus on its critical role in drug discovery and the development of advanced research tools.

Core Techniques and Methodologies in Functional Genomics

Functional genomics employs a wide array of techniques to measure molecular activities at different biological levels, from DNA to RNA to protein. These techniques are characterized by their multiplex nature, allowing for the parallel measurement of the abundance and activities of many or all gene products within a biological sample [1].

Table 1: Key Functional Genomics Techniques by Biological Level

| Biological Level | Technique | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | ChIP-sequencing [1] | Identifying DNA-protein interaction sites [1] | Genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding or histone modifications [1] |

| ATAC-seq [1] | Assaying regions of accessible chromatin [1] | Identifies candidate regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) [1] | |

| Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs) [1] | Testing the cis-regulatory activity of DNA sequences [1] | High-throughput functional testing of thousands of regulatory elements in parallel [1] | |

| RNA | RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) [1] [4] | Profiling gene expression and transcriptome analysis [1] [4] | Direct, quantitative, and does not require prior knowledge of gene sequences [4] |

| Microarrays [1] [4] | Measuring mRNA abundance [1] | Well-studied, high-throughput method for expression profiling [4] | |

| Perturb-seq [1] | Coupling CRISPR with single-cell RNA sequencing | Measures the effect of single-gene knockdowns on the entire transcriptome in single cells [1] | |

| Protein | Mass Spectrometry (MS) / AP-MS [1] | Identifying proteins and protein-protein interactions [1] | High-throughput method for identifying and quantifying proteins and complex members [1] |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [1] [4] | Detecting physical protein-protein interactions [1] | Relatively simple system for identifying interacting protein partners [1] [4] | |

| Gene Function | CRISPR Knockouts [1] [5] | Determining gene function via deletion | Precise, programmable, and adaptable for genome-wide screens [5] |

| Deep Mutational Scanning [1] | Assessing the functional impact of numerous protein variants [1] | Multiplexed assay allowing effects of thousands of mutations to be characterized simultaneously [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols in Functional Genomics

Genome-Wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Screening

CRISPR-based screening is a cornerstone of modern functional genomics for unbiased assessment of gene function [6]. The following protocol outlines a typical pooled screen to identify genes essential for cell proliferation.

- â‘ Library Design: A complex pool of lentiviral transfer plasmids is generated, each containing a single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence targeting a specific gene and a barcode unique to that sgRNA. Genome-wide libraries target every gene in the genome with multiple sgRNAs per gene [6] [5].

- â‘¡ Viral Production & Transduction: Lentiviral particles are produced from the plasmid library. Target cells are transduced at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA, and selection (e.g., puromycin) is applied to generate a stable mutant cell pool [6].

- â‘¢ Screening & Selection: The pool of mutant cells is passaged for multiple cell doublings. Cells whose proliferation is impaired due to the knockout of an essential gene will be depleted from the population over time [5].

- â‘£ Genomic DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Genomic DNA is harvested from the cell pool at the beginning (T0) and end (Tend) of the experiment. The sgRNA sequences and their associated barcodes are amplified by PCR and quantified via next-generation sequencing [6].

- ⑤ Data Analysis: Bioinformatic tools (e.g., BAGEL2) are used to compare the abundance of each sgRNA between T0 and Tend. sgRNAs that are significantly depleted in the End sample identify genes that are essential for proliferation under the screened condition [7].

Quantitative Comparison of ChIP-seq Datasets (Differential Binding)

ChIP-comp is a statistical method for comparing multiple ChIP-seq datasets to identify genomic regions with significant differences in protein binding or histone modification [8].

- â‘ Peak Calling & Candidate Region Definition: Peaks are independently called for each individual ChIP-seq dataset using a standard algorithm (e.g., MACS). The union of all peaks from all datasets is taken to form a single set of candidate regions for comparative analysis [8].

- â‘¡ Background Estimation & Normalization: For each candidate region and dataset, the read counts from the IP (Immunoprecipitation) experiment and the control (Input) experiment are recorded. The control data is used to estimate the non-uniform genomic background, which is crucial for accurate quantitative comparison. Normalization is performed to account for different signal-to-noise ratios between experiments [8].

- ③ Statistical Modeling: The IP read counts (Yij) for each candidate region (i) in each dataset (j) are modeled using a Poisson distribution. The underlying Poisson rate is a function of the estimated background (λij) and the biological signal (S_ij), which is further decomposed into experiment-specific and biological-replicate-specific components within a linear model framework [8].

- â‘£ Hypothesis Testing: For a given candidate region, the model tests whether the biological signal differs significantly across experimental conditions (e.g., different treatments or cell types). Genomic regions with statistically significant differences are reported as differential binding sites [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful functional genomics research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. Proper design and currency of these tools are critical, as outdated genome annotations can lead to false results [9].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR gRNA Libraries [9] [5] | A pooled collection of guide RNA (gRNA) sequences designed to target and knockout every gene in the genome. | Genome-wide loss-of-function screens to identify genes essential for cell viability or drug resistance [5]. |

| RNAi Reagents (siRNA/shRNA) [1] [9] | Synthetic short interfering RNA (siRNA) or plasmid-encoded short hairpin RNA (shRNA) used to transiently knock down gene expression via the RNAi pathway. | Rapid, transient knockdown of gene expression to assess phenotypic consequences without permanent genetic modification [1]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors [6] | Engineered viral delivery systems derived from HIV-1, used to stably introduce genetic constructs (e.g., gRNAs, shRNAs) into a wide variety of cell types, including non-dividing cells. | Creating stable cell lines for persistent gene knockdown or knockout in primary cells or cell lines [6]. |

| Validated Antibodies [4] | Specific antibodies for targeting proteins of interest in assays like Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) or ELISA. | Enriching for DNA fragments bound by a specific transcription factor (ChIP-seq) or quantifying protein expression levels [4]. |

| Barcoded Constructs [1] [6] | Genetic constructs containing unique DNA sequence "barcodes" that allow for the multiplexed tracking and quantification of individual variants within a complex pool. | Tracking the abundance of individual gRNAs in a pooled CRISPR screen or protein variants in a deep mutational scan [1] [6]. |

| Calcein Blue AM | Calcein Blue AM, MF:C21H23NO11, MW:465.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Clencyclohexerol-d10 | Clencyclohexerol-d10, MF:C14H20Cl2N2O2, MW:329.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Context-Dependent Functional Interactions

Advanced network analysis of CRISPR screening data can reveal how biological processes are rewired by specific genetic or cellular contexts, such as oncogenic mutations [7].

Application in Drug Discovery and Target Validation

Functional genomics is revolutionizing drug discovery by enabling the systematic identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets. Its primary value lies in linking genes to disease, thereby helping to select the right target—the single most important decision in the drug discovery process [5]. By using CRISPR to knock out every gene in the genome and observing the phenotypic consequences, researchers can identify genes that are essential in specific disease contexts, such as in cancer cells with certain mutations, while being dispensable in healthy cells [7] [5]. This approach not only identifies new targets but also can reveal mechanisms of resistance to existing therapies, guiding the development of more effective combination treatments [5]. The pairing of genome editing technologies with bioinformatics and artificial intelligence allows for the efficient analysis of large-scale screening data, maximizing the chances of clinical success [5].

A primary ambition of modern functional genomics is to move beyond the detection of statistical associations and establish true causal links between genetic variants and phenotypic outcomes. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified hundreds of thousands of genetic variants correlated with complex traits and diseases. However, correlation does not imply causation—a significant challenge given that trait-associated variants are often in linkage disequilibrium with many other variants and frequently reside in non-coding regulatory regions with unclear functional impacts [10]. Establishing causality is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms, identifying druggable targets, and developing personalized therapeutic strategies. This technical guide examines the advanced methodologies and experimental frameworks that enable researchers to bridge this critical gap between genotype-phenotype association and causation, with a focus on approaches that provide mechanistic insights into complex biological systems.

Key Methodological Frameworks for Causal Inference

Several sophisticated statistical and computational frameworks have been developed to establish causal relationships in genomic data. These methods leverage different principles and data types to strengthen causal inference, each with distinct strengths and applications as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Methodological Frameworks for Establishing Causal Links

| Method | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Primary Output | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendelian Randomization (MR) | Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to test causal relationships between molecular phenotypes and complex traits [10] [11] | GWAS summary statistics for exposure and outcome traits | Causal effect estimates with confidence intervals | Reduces confounding; establishes directionality |

| Multi-omics Integration (OPERA) | Jointly analyzes GWAS and multiple xQTL datasets to identify pleiotropic associations through shared causal variants [10] | Summary statistics from GWAS and ≥2 omics layers (eQTL, pQTL, mQTL, etc.) | Posterior probability of association (PPA) for molecular phenotypes | Reveals mechanistic pathways; integrates multiple evidence layers |

| Knockoff-Based Inference (KnockoffScreen) | Generates synthetic null variants to distinguish causal from non-causal associations while controlling FDR [12] | Whole-genome sequencing data; case-control or quantitative traits | Putative causal variants with controlled false discovery rate | Controls FDR under arbitrary correlation structures; prioritizes causal over LD-driven associations |

| Phenotype-Genotype Association Grid | Visual data mining of large-scale association results across multiple phenotypes and genetic models [13] | Association test results (p-values, effect sizes) for multiple trait-SNP pairs | Interactive visualization of association patterns | Identifies pleiotropic patterns; facilitates hypothesis generation |

| Heritable Genotype Contrast Mining | Uses frequent pattern mining to identify genetic interactions distinguishing phenotypic subgroups [14] | Family-based genetic data with detailed phenotypic subtyping | Gene combinations associated with specific phenotypic subgroups | Reveals epistatic effects; personalizes associations to disease subtypes |

Advanced Multi-Omics Integration

The OPERA framework represents a significant advancement in causal inference by simultaneously modeling relationships across multiple molecular layers. This Bayesian approach analyzes GWAS signals alongside various molecular quantitative trait loci (xQTLs)—including expression QTLs (eQTLs), protein QTLs (pQTLs), methylation QTLs (mQTLs), chromatin accessibility QTLs (caQTLs), and splicing QTLs (sQTLs) [10]. OPERA calculates posterior probabilities for different association configurations between molecular phenotypes and complex traits, enabling researchers to distinguish whether a GWAS signal is shared with specific molecular mechanisms through pleiotropy. This multi-omics integration is particularly powerful for identifying putative causal genes and functional mechanisms at GWAS loci, moving beyond mere association to propose testable biological hypotheses about regulatory mechanisms underlying complex traits.

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Causal Relationships

Multi-Omics Causal Variant Prioritization

Objective: Identify molecular phenotypes that share causal variants with complex traits of interest using summary-level data from GWAS and multiple xQTL studies.

Materials:

- GWAS summary statistics for target trait

- xQTL summary statistics for ≥2 molecular data types (eQTL, pQTL, mQTL, etc.)

- Genomic reference panel for linkage disequilibrium estimation

- OPERA software package or equivalent multi-omics integration tool

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and QC:

- Process all summary statistics to uniform genomic build

- Remove variants with minor allele frequency < 0.01 or imputation quality score < 0.6

- Annotate all variants with standardized genomic coordinates

Locus Definition:

- Identify independent GWAS signals using LD clumping (r² < 0.01 within 1Mb window)

- Define genomic loci as 2Mb windows centered on lead variants, merging overlapping regions

Prior Estimation:

- Select quasi-independent loci representing all molecular phenotypes

- Run Bayesian model to estimate prior probabilities (Ï€) for association configurations

Joint Association Testing:

- For each locus, compute SMR test statistics for all molecular phenotype-trait pairs

- Calculate posterior probabilities for all possible association configurations

- Compute marginal posterior probabilities of association (PPA) for each molecular phenotype

Multi-omics HEIDI Testing:

- Perform heterogeneity tests to distinguish pleiotropy from linkage

- Filter associations where distinct causal variants underlie xQTL and GWAS signals

Interpretation:

- Prioritize molecular phenotypes with PPA > 0.8 for functional validation

- Examine patterns of multi-omics convergence to infer regulatory hierarchies

Expected Output: A prioritized list of molecular phenotypes (genes, proteins, methylation sites) likely sharing causal variants with the trait of interest, with associated posterior probabilities and evidence strength across omics layers [10].

Causal Variant Discovery in Whole-Genome Sequencing Data

Objective: Detect and localize putative causal rare and common variants in whole-genome sequencing studies while controlling false discovery rate.

Materials:

- Whole-genome sequencing data (VCF format)

- Phenotypic data (case-control or quantitative)

- Covariate data (principal components, clinical covariates)

- KnockoffScreen software package

- High-performance computing cluster

Procedure:

- Knockoff Generation:

- Implement sequential knockoff generator to create synthetic variants

- Ensure exchangeability property: original and knockoff variants maintain identical correlation structure

- Generate multiple knockoff copies (typically 10-20) for improved power

Genome-wide Screening:

- Define scanning windows across the genome (suggested: 1-5kb sliding windows)

- For each window, compute association test statistics for original and knockoff variants

- Use ensemble testing approach combining burden, SKAT, and functional annotation tests

Feature Statistics Calculation:

- Compute importance measure W for each original window and its knockoff

- Calculate feature statistic for each window: ( W_j ) = original importance - max(knockoff importance)

- Repeat across multiple knockoff copies and aggregate statistics

FDR-Controlled Selection:

- Apply knockoff filter to select windows with feature statistics exceeding threshold

- Determine threshold to control FDR at desired level (e.g., 10%)

- Report selected windows as putative causal regions

Fine-mapping:

- Within significant windows, prioritize individual variants with highest contribution to association signal

- Annotate prioritized variants with functional genomic data (ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics)

Expected Output: A set of putative causal variants or genomic regions associated with the trait, with controlled false discovery rate, prioritized for functional validation [12].

Visualization and Data Interpretation Frameworks

Visual Workflows for Causal Inference

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting complex causal relationships in genomic data. The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and analytical frameworks using standardized visual grammar.

Diagram 1: Multi-domain phenotyping for enhanced GWAS power. Complex algorithms integrating multiple EHR domains improve causal variant discovery.

Diagram 2: OPERA multi-omics causal inference workflow. Integration of multiple molecular QTL datasets enhances identification of pleiotropic associations.

Visualization Tools for Genomic Data

Effective visualization bridges algorithmic approaches and researcher interpretation, particularly for complex 3D genomic relationships. Recent advances include Geometric Diagrams of Genomes (GDG), which provides a visual grammar for representing genome organization at different scales using standardized geometric forms: circles for chromosome territories, squares for compartments, triangles for domains, and lines for loops [15]. For accessibility, researchers should avoid red-green color combinations (problematic for color-blind readers) and instead use high-contrast alternatives like green-magenta or yellow-blue, with grayscale channels for individual data layers [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Causal Genomics

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Statistics | Data Resource | Provides association signals between variants and complex traits | Foundation for MR, colocalization, and multi-omics analyses [10] [11] |

| xQTL Datasets (eQTL, pQTL, mQTL, etc.) | Data Resource | Maps genetic variants to molecular phenotype associations | Enables identification of molecular intermediates in OPERA framework [10] |

| LD Reference Panels | Data Resource | Provides linkage disequilibrium structure for specific populations | Essential for knockoff generation, fine-mapping, and colocalization tests [10] [12] |

| OPERA Software | Computational Tool | Bayesian analysis of GWAS and multi-omics xQTL summary statistics | Joint identification of pleiotropic associations across omics layers [10] |

| KnockoffScreen | Computational Tool | Genome-wide screening with knockoff statistics | FDR-controlled discovery of putative causal variants in WGS data [12] |

| SHEPHERD | Computational Tool | Knowledge-grounded deep learning for rare disease diagnosis | Causal gene discovery using phenotypic and genotypic data [17] |

| PGA Grid | Visualization Tool | Interactive display of phenotype-genotype association results | Pattern identification across multiple traits and genetic models [13] |

| Human Phenotype Ontology | Ontology Resource | Standardized vocabulary for phenotypic abnormalities | Phenotypic characterization for rare disease diagnosis [17] |

| 4-Epiminocycline | 4-Epiminocycline, CAS:43168-51-0, MF:C23H27N3O7, MW:457.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dimethenamid-d3 | Dimethenamid-d3, MF:C12H18ClNO2S, MW:278.81 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Establishing causal links between genotype and phenotype requires moving beyond traditional association studies to integrated approaches that incorporate multiple evidence layers. Methodologies such as multi-omics integration, knockoff-based inference, and sophisticated phenotyping algorithms significantly enhance our ability to distinguish causal from correlative relationships. The experimental protocols and tools outlined in this guide provide a framework for researchers to implement these advanced approaches in their investigations. As functional genomics continues to evolve, the integration of increasingly diverse molecular data types—considering spatiotemporal context and cellular specificity—will further refine our capacity to identify true causal mechanisms underlying complex traits and diseases, ultimately accelerating therapeutic development and personalized medicine.

The Shift from Candidate-Gene to Genome-Wide, High-Throughput Approaches

The field of genetic research has undergone a profound transformation, moving from targeted candidate-gene studies to comprehensive genome-wide, high-throughput approaches. This paradigm shift represents a fundamental change in how researchers explore the relationship between genotype and phenotype. While candidate-gene studies focused on pre-selected genes based on existing biological knowledge, genome-wide approaches enable hypothesis-free exploration of the entire genome, allowing for novel discoveries beyond current understanding. This transition has been driven by technological advancements in sequencing technologies, computational power, and statistical methodologies, fundamentally reshaping functional genomics research tools and design principles.

The limitations of candidate-gene approaches have become increasingly apparent, including their reliance on incomplete biological knowledge, inherent biases toward known pathways, and inability to discover novel genetic associations. In contrast, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have illuminated the majority of the genotypic space for numerous organisms, including humans, maize, rice, and Arabidopsis [18]. For any researcher willing to define and score a phenotype across many individuals, GWAS presents a powerful tool to reconnect traits to their underlying genetics, enabling unprecedented insights into human biology and disease [19].

Technological Drivers of the Transition

The Rise of Next-Generation Sequencing

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics by making large-scale DNA and RNA sequencing faster, cheaper, and more accessible than ever. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, which was time-intensive and costly, NGS enables simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, democratizing genomic research and enabling high-impact projects like the 1000 Genomes Project and the UK Biobank [19].

Key Advancements in NGS Technology:

- Illumina's NovaSeq X has redefined high-throughput sequencing, offering unmatched speed and data output for large-scale projects

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies has expanded the boundaries of read length, enabling real-time, portable sequencing

- Continuing cost reduction has made large-scale genomic studies economically feasible for more research institutions

Computational and Analytical Advances

The massive scale and complexity of genomic datasets demand advanced computational tools for interpretation. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms have emerged as indispensable in genomic data analysis, uncovering patterns and insights that traditional methods might miss [19].

Critical Computational Innovations:

- Variant Calling: Tools like Google's DeepVariant utilize deep learning to identify genetic variants with greater accuracy than traditional methods

- Disease Risk Prediction: AI models analyze polygenic risk scores to predict an individual's susceptibility to complex diseases

- Cloud Computing: Platforms like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Genomics provide scalable infrastructure to store, process, and analyze terabytes of genomic data efficiently

- Statistical Methodologies: Advanced mixed models that account for population structure and relatedness have addressed early limitations in GWAS

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Analysis Approaches

| Feature | Candidate-Gene Approach | Genome-Wide Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis Framework | Targeted, hypothesis-driven | Untargeted, hypothesis-generating |

| Genomic Coverage | Limited to pre-selected genes | Comprehensive genome coverage |

| Discovery Potential | Restricted to known biology | Unbiased novel discovery |

| Throughput | Low to moderate | High to very high |

| Cost per Data Point | Higher for limited targets | Lower per data point due to scale |

| Technical Requirements | Standard molecular biology | Advanced computational infrastructure |

| Sample Size Requirements | Smaller cohorts | Large sample sizes for power |

| Multiple Testing Burden | Minimal | Substantial, requiring correction |

Methodological Comparison: Candidate-Gene vs. Genome-Wide Approaches

Fundamental Limitations of Candidate-Gene Studies

Candidate-gene studies suffer from two fundamental constraints that genome-wide approaches overcome. First, they can only assay allelic diversity within the pre-selected genes, potentially missing important associations elsewhere in the genome. Second, their resolution is limited by the initial selection criteria, which may be based on incomplete or inaccurate biological understanding [18]. This approach fundamentally assumes comprehensive prior knowledge of biological pathways, an assumption that often proves flawed given the complexity of biological systems.

The reliance on existing biological knowledge creates a self-reinforcing cycle where only known pathways are investigated, potentially missing novel biological mechanisms. Furthermore, the failure to account for population structure and cryptic relatedness in many candidate-gene studies has led to numerous false positives and non-replicable findings, undermining confidence in this approach.

Advantages of Genome-Wide Association Studies

GWAS overcome the main limitations of candidate-gene analysis by evaluating associations across the entire genome without prior assumptions about biological mechanisms. This approach was pioneered nearly a decade ago in human genetics, with nearly 1,500 published human GWAS to date, and has now been routinely applied to model organisms including Arabidopsis thaliana and mouse, as well as non-model systems including crops and cattle [18].

Key Advantages of GWAS:

- Comprehensive Coverage: Assays genetic variation across the entire genome

- Unbiased Discovery: Identifies novel associations beyond current biological knowledge

- High Resolution: Mapping resolution determined by natural recombination rates across populations

- Diverse Allelic Sampling: Captures genetic diversity present in natural populations rather than just lab crosses

The basic approach in GWAS involves evaluating the association between each genotyped marker and a phenotype of interest scored across a large number of individuals. This requires careful consideration of sample size, population structure, genetic architecture, and multiple testing corrections to ensure robust, replicable findings.

Table 2: Technical Requirements for Genome-Wide Studies

| Component | Minimum Requirements | Optimal Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Hundreds for simple traits in inbred organisms | Thousands for complex traits in outbred populations |

| Marker Density | 250,000 SNPs for organisms like Arabidopsis | Millions of markers for human GWAS |

| Statistical Power | 80% power for large-effect variants | >95% power for small-effect variants |

| Multiple Testing Correction | Bonferroni correction | False Discovery Rate (FDR) methods |

| Population Structure Control | Principal Component Analysis | Mixed models with kinship matrices |

| Sequencing Depth | 30x for whole genome sequencing | 60x for comprehensive variant detection |

| Computational Storage | Terabytes for moderate studies | Petabytes for large consortium studies |

Experimental Design and Methodological Framework

GWAS Workflow and Experimental Protocol

The standard GWAS workflow involves multiple critical steps, each requiring careful execution to ensure valid results. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive process from study design through biological validation:

Detailed GWAS Experimental Protocol:

Study Design and Sample Collection

- Define precise phenotype measurement protocols

- Determine appropriate sample size based on power calculations

- Select diverse population samples to capture genetic variation

- Obtain informed consent and ethical approvals for human studies

Genotyping and Quality Control

- Perform high-density SNP genotyping using array technologies

- Apply sample quality filters: call rate >95%, gender verification, relatedness check (remove one from pairs with IBD >0.125)

- Apply variant quality filters: call rate >95%, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p > 1×10â»â¶, minor allele frequency appropriate for study power

- Assess population structure using principal component analysis

Imputation and Association Testing

- Impute to reference panels to increase marker density

- Perform association testing using mixed models accounting for genetic relatedness

- Apply genomic control to correct for residual population stratification

- Implement multiple testing correction (Bonferroni or False Discovery Rate)

Replication and Validation

- Identify top associated loci for replication in independent cohorts

- Perform meta-analysis across discovery and replication datasets

- Conduct functional validation experiments for prioritized variants

Integration with Functional Genomics Tools

Modern genome-wide approaches increasingly integrate with functional genomics tools to move from association to causation. This integration has created a powerful framework for biological discovery:

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Multi-Omics Integration in Functional Genomics

While genomics provides valuable insights into DNA sequences, it represents only one layer of biological information. Multi-omics approaches combine genomics with other data types to provide a comprehensive view of biological systems [19]. This integration has become increasingly important for understanding complex traits and diseases.

Key Multi-Omics Components:

- Transcriptomics: RNA expression levels to connect genetic variants to gene regulation

- Proteomics: Protein abundance and interactions to understand functional consequences

- Metabolomics: Metabolic pathways and compounds as intermediate phenotypes

- Epigenomics: Epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation and histone marks

Multi-omics integration has proven particularly valuable in cancer research, where it helps dissect the tumor microenvironment and reveal interactions between cancer cells and their surroundings. Similarly, in cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, combining genomics with other omics layers has identified critical biomarkers and pathways [19].

AI and Machine Learning in Genomic Analysis

Artificial intelligence has transformed genomic data analysis by providing tools to manage the enormous complexity and scale of genome-wide datasets. AI algorithms, particularly machine learning models, can identify patterns, predict genetic variations, and accelerate disease association discoveries that traditional methods might miss [19].

Critical AI Applications:

- Variant Calling: Deep learning models like DeepVariant achieve superior accuracy in identifying genetic variants from sequencing data

- Polygenic Risk Scoring: AI integrates multiple weak-effect variants to predict disease susceptibility

- Drug Target Identification: Machine learning analyzes genomic data to prioritize therapeutic targets

- Functional Prediction: AI models predict the functional impact of non-coding variants

The integration of AI with multi-omics data has further enhanced its capacity to predict biological outcomes, contributing significantly to advancements in precision medicine and functional genomics [19].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SNP Genotyping Arrays | Genome-wide variant profiling | Illumina Infinium, Affymetrix Axiom |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Comprehensive variant detection | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore |

| Library Preparation Kits | NGS sample preparation | Illumina Nextera, KAPA HyperPrep |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Selective region capture | Illumina TruSeq, Agilent SureSelect |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | Functional validation | Brunello, GeCKO, SAM libraries |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Kits | Cellular heterogeneity analysis | 10x Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Tissue context gene expression | 10x Visium, Nanostring GeoMx |

| Epigenetic Profiling Kits | DNA methylation, chromatin state | Illumina EPIC array, CUT&Tag kits |

Challenges and Future Directions

Statistical and Methodological Challenges

Despite their power, genome-wide approaches face significant challenges that require careful methodological consideration. The "winner's curse" phenomenon, where effect sizes are overestimated in discovery cohorts, remains a concern. Rare variants with potentially large effects are particularly difficult to detect without extremely large sample sizes or specialized statistical approaches [18].

Key Statistical Challenges:

- Rare Variant Detection: Variants with frequency <1% require specialized collapsing methods or enormous sample sizes

- Population Stratification: Residual confounding despite advanced statistical controls

- Polygenic Architecture: Many traits involve hundreds or thousands of small-effect variants

- Multiple Testing: Genome-wide significance thresholds (typically p < 5×10â»â¸) reduce power

- Genetic Heterogeneity: Different genetic variants can cause similar phenotypes in different populations

Sample size requirements vary substantially based on genetic architecture. While some traits in inbred organisms like Arabidopsis can be successfully analyzed with few hundred individuals, complex human diseases often require tens or hundreds of thousands of samples to detect variants with small effect sizes [18].

Ethical Considerations and Data Security

The rapid growth of genomic datasets has amplified concerns around data privacy and ethical use. Genomic data represents particularly sensitive information because it not only reveals personal health information but also information about relatives. Breaches can lead to genetic discrimination and misuse of personal health information [19].

Critical Ethical Considerations:

- Informed Consent: Ensuring participants understand data sharing implications in multi-omics studies

- Data Security: Implementing advanced encryption and access controls for sensitive genomic data

- Equitable Access: Addressing disparities in genomic service accessibility across different regions and populations

- Return of Results: Developing frameworks for communicating clinically actionable findings to participants

Cloud computing platforms have responded to these challenges by implementing strict regulatory frameworks compliant with HIPAA, GDPR, and other data protection standards, enabling secure collaboration while protecting participant privacy [19].

The shift from candidate-gene to genome-wide, high-throughput approaches represents one of the most significant transformations in modern genetics. This paradigm shift has enabled unprecedented discoveries of genetic variants underlying complex traits and diseases, moving beyond the constraints of prior biological knowledge to enable truly novel discoveries. The integration of genome-wide approaches with functional genomics tools, multi-omics technologies, and advanced computational methods has created a powerful framework for understanding the genetic architecture of complex traits.

As genomic technologies continue to evolve, with single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and CRISPR functional genomics providing increasingly refined views of biological systems, the comprehensive nature of genome-wide approaches will continue to drive discoveries in basic biology and translational medicine. However, realizing the full potential of these approaches will require continued attention to methodological rigor, ethical considerations, and equitable implementation to ensure these powerful tools benefit all populations.

Functional genomics is undergoing a transformative shift, moving from observing static sequences to dynamically probing and designing biological systems. This evolution is powered by the convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), single-cell resolution technologies, and high-throughput genomic engineering. These tools are enabling researchers to address the foundational questions of gene function, the dynamics of gene regulation, and the complexity of genetic interaction networks with unprecedented precision and scale. This technical guide synthesizes the most advanced methodologies and tools that are redefining the functional genomics landscape, providing a framework for their application in research and drug development.

Deciphering Gene Function with AI and Functional Genomics

A primary challenge in genomics is moving from a gene sequence to an understanding of its function. Traditional methods are often slow and target single genes. Recent advances use AI to predict function from genomic context and large-scale functional genomics to experimentally validate these predictions across entire biological systems.

AI-Driven Functional Prediction and Design

Semantic Design with Genomic Language Models: A groundbreaking approach involves using genomic language models, such as Evo, to perform "semantic design." This method is predicated on the biological principle of "guilt by association," where genes with related functions are often co-located in genomes. Evo, trained on vast prokaryotic genomic datasets, learns these distributional semantics [20].

- Methodology: Researchers provide the model with a DNA "prompt" sequence encoding the genomic context of a known function (e.g., a characterized toxin gene). Evo then "autocompletes" this prompt by generating novel, syntactically correct DNA sequences that are semantically related to the input, effectively designing new genes or multi-gene systems [20].

- Experimental Validation: This approach has been experimentally validated by generating functional type II toxin–antitoxin (T2TA) systems and anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins. Generated sequences were filtered in silico for features like protein-protein interaction potential and novelty. Subsequent growth inhibition assays confirmed the function of novel toxins (e.g., EvoRelE1), while phage infection assays validated the activity of generated Acrs, some of which shared no significant sequence or predicted structural similarity to known natural proteins [20].

Predicting Disease-Reversal Targets with Graph Neural Networks: For complex diseases in human cells, where multi-gene dysregulation is common, tools like PDGrapher offer a paradigm shift from single-target to network-based targeting [21].

- Methodology: PDGrapher is a graph neural network that maps the complex relationships between genes, proteins, and signaling pathways inside cells. It is trained on datasets of diseased cells pre- and post-treatment. The model simulates the effects of inhibiting or activating specific gene targets, identifying the minimal set of interventions that can shift a cell from a diseased to a healthy state [21].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Profile: Create a molecular profile of a diseased cell.

- Model: Input the profile into PDGrapher to map the dysfunctional interaction network.

- Simulate: The model performs in-silico perturbations on network nodes (genes/proteins).

- Identify: It ranks single or combination drug targets that are predicted to reverse the disease phenotype.

- Validation: In tests across 19 datasets spanning 11 cancer types, PDGrapher accurately predicted known drug targets that were withheld from training and identified new candidates, such as KDR (VEGFR2) and TOP2A in non-small cell lung cancer, which align with emerging clinical and preclinical evidence [21].

High-Throughput Experimental Characterization

Large-scale functional genomics projects, such as those funded by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI), leverage omics technologies to link genes to functions in diverse organisms, from microbes to bioenergy crops. The table below summarizes key research directions and their methodologies [22].

Table 1: High-Throughput Functional Genomics Approaches

| Research Focus | Organism | Core Methodology | Key Functional Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought Tolerance & Wood Formation [22] | Poplar Trees | Transcriptional regulatory network mapping via DAP-seq | Identification of transcription factors controlling drought-resistance and wood-formation traits. |

| Cyanobacterial Energy Capture [22] | Cyanobacteria | High-throughput testing of rhodopsin variants; Machine Learning | Optimization of microbial light capture for bioenergy. |

| Secondary Metabolite Function [22] | Cyanobacteria | Linking Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) to metabolites | Determination of metabolite roles in ecosystem interactions (e.g., antifungal, anti-predation). |

| Silica Biomineralization [22] | Diatoms | DNA synthesis & sequencing to map regulatory proteins | Identification of genes controlling silica shell formation for biomaterials inspiration. |

| Anaerobic Chemical Production [22] | Eubacterium limosum | Engineering methanol conversion pathways | Production of succinate and isobutanol from renewable feedstocks. |

Analyzing Gene Regulation from Single Molecules to Single Cells

Understanding gene regulation requires observing the dynamic interactions of macromolecular complexes with DNA and RNA. Cutting-edge technologies now allow this observation at the ultimate resolutions: single molecules and single cells.

Single-Molecule Resolution of Regulatory Dynamics

Traditional genomics provides static snapshots of gene regulation. The emerging field of single-molecule genomics and microscopy directly observes the kinetics and dynamics of transcription, translation, and RNA processing in living cells [23].

- Key Techniques:

- Single-Molecule Microscopy: Allows direct visualization of the assembly, binding duration, and dissociation dynamics of transcription factors and RNA polymerase at specific genomic loci in real time [23].

- Single-Molecule Genomics (e.g., DNA Footprinting): Provides nucleotide-level information on protein-DNA interactions and chromatin accessibility, revealing the kinetics of regulatory processes [23].

- Applications: These methods are used to study fundamental parameters such as transcription factor binding kinetics, the role of phase-separated condensates in gene activation, and the dynamics of epigenetic memory [23]. The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized pipeline for a single-molecule genomics experiment.

Multi-Omic Single-Cell Analysis of Genomic Variants

Most disease-associated genetic variants lie in non-coding regulatory regions. The single-cell DNA-RNA-sequencing (SDR-seq) tool enables the simultaneous measurement of DNA sequence and RNA expression from thousands of individual cells, directly linking genetic variants to their functional transcriptional consequences [24].

- Methodology:

- Fixation: Cells are fixed to preserve RNA integrity.

- Emulsion Droplets: Single cells are compartmentalized in oil-water emulsion droplets.

- Parallel Barcoding: Both DNA and RNA from the same cell are tagged with a unique cellular barcode during library preparation.

- Sequencing & Analysis: High-throughput sequencing is followed by computational deconvolution using custom tools to link variants to gene expression patterns cell-by-cell [24].

- Application: In a study of B-cell lymphoma, SDR-seq revealed that cancer cells with a higher burden of genetic variants were more likely to be in a malignant state, demonstrating a direct link between non-coding variant load and disease aggression [24].

Mapping Genetic Interaction Networks

Complex phenotypes and diseases often arise from non-linear interactions between multiple genes and pathways. Mapping these epistatic networks is a major challenge, now being addressed by interpretable AI models.

Visible Neural Networks for Epistasis Detection

Standard neural networks can model genetic interactions but are often "black boxes." Visible Neural Networks (VNNs), such as those in the GenNet framework, embed prior biological knowledge (e.g., SNP-gene-pathway hierarchies) directly into the network architecture, creating a sparse and interpretable model [25].

- Methodology:

- Structured Architecture: The input layer consists of SNPs, which are connected to nodes representing the genes they belong to. These gene nodes connect to pathway nodes, which finally connect to the output (e.g., disease risk) [25].

- Training: The network is trained on genotyping data (e.g., from GWAS) to predict a phenotype.

- Interaction Detection: Post-training, specialized interpretation methods like Neural Interaction Detection (NID) and Deep Feature Interaction Maps (DFIM) are applied to the trained VNN to detect significant non-linear interactions between genes and pathways [25].

- Validation: On simulated genetic data from GAMETES and EpiGEN, these methods successfully recovered known ground-truth epistatic pairs. When applied to an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) case-control dataset, they identified seven significant epistasis pairs, demonstrating utility in real-world complex disease genetics [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

The following table catalogs key computational and experimental platforms that constitute the modern toolkit for functional genomics research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Functional Genomics

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evo [20] | Genomic Language Model | Generative AI for DNA sequence design | Semantic design of novel functional genes and multi-gene systems. |

| PDGrapher [21] | Graph Neural Network | Identifying disease-reversal drug targets | Predicting single/combination therapies for complex diseases like cancer. |

| CRISPR-GPT [26] | AI Assistant / LLM | Gene-editing experiment copilot | Automating CRISPR design, troubleshooting, and optimizing protocols for novices and experts. |

| SDR-seq [24] | Wet-lab Protocol | Simultaneous scDNA & scRNA sequencing | Directly linking non-coding genetic variants to gene expression changes in thousands of single cells. |

| GenNet VNN [25] | Interpretable AI Framework | Modeling hierarchical genetic data | Detecting non-linear gene-gene interactions in GWAS data with built-in interpretability. |

| DAVID [27] | Bioinformatics Database | Functional annotation of gene lists | Identifying enriched biological themes (GO terms, pathways) from large-scale genomic data. |

| Capsiamide-d3 | Capsiamide-d3, MF:C17H35NO, MW:272.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Hydroxy Bosentan-d4 | Hydroxy Bosentan-d4, CAS:1065472-91-4, MF:C27H29N5O7S, MW:571.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Semantic Design of a Toxin-Antitoxin System

This protocol outlines the steps for using the Evo model to design and validate a novel type II toxin-antitoxin (T2TA) system [20].

- Prompt Engineering:

- Curate a set of genomic sequence prompts from known T2TA systems. Prompts can include the toxin gene, antitoxin gene, their reverse complements, or upstream/downstream genomic context.

- Input these prompts into the Evo 1.5 model to generate a library of novel DNA sequence responses.

- In Silico Filtering and Analysis:

- Translate generated sequences and filter for open reading frames (ORFs).

- Predict protein-protein interactions between generated toxin and antitoxin pairs.

- Apply a novelty filter (e.g., <70% sequence identity to known proteins in databases) to ensure exploration of new sequence space.

- Molecular Cloning:

- Synthesize the top candidate toxin and antitoxin gene pairs.

- Clone the toxin gene alone, and the toxin-antitoxin pair together, into inducible expression plasmids.

- Functional Validation - Growth Inhibition Assay:

- Transform the toxin-only plasmid and the toxin-antitoxin plasmid into an appropriate bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli).

- Culture transformed bacteria in liquid media and induce toxin expression.

- Measure cell density (OD600) over time for both cultures and an empty-vector control.

- Expected Outcome: Cultures expressing only the toxin will show significant growth inhibition compared to the control, while cultures co-expressing the toxin and its cognate antitoxin will show restored growth, confirming a functional pair.

Protocol: Single-Cell DNA-RNA Sequencing (SDR-seq)

This protocol describes the steps for using SDR-seq to link genetic variants to gene expression in a population of cells (e.g., cancer cells) [24].

- Cell Fixation:

- Harvest and wash cells. Resuspend in a fixative solution (e.g., formaldehyde-based) to crosslink and preserve nucleic acids. Quench the cross-linking reaction.

- Single-Cell Partitioning and Barcoding:

- Load fixed cells, lysis reagents, and barcoded beads into a microfluidic device to generate oil-water emulsion droplets, ensuring a high probability of one cell per droplet.

- Within each droplet, cells are lysed, and both genomic DNA and RNA are reverse-crosslinked and released.

- The barcoded beads release primers that uniquely tag all DNA and RNA from a single cell with the same cellular barcode during subsequent steps.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Perform separate but coordinated library preparations for DNA and RNA from the pooled droplet contents.

- The DNA library captures genetic variants, while the RNA library captures the transcriptome.

- Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput NGS platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq X).

- Computational Analysis:

- Use a custom computational decoder to demultiplex the sequenced reads based on their cellular barcodes, assigning each read to its cell of origin.

- Call genetic variants (SNPs, indels) from the DNA reads for each cell.

- Quantify gene expression (e.g., count transcripts) from the RNA reads for each cell.

- Perform association analysis to correlate the presence of specific variants with changes in gene expression across the single-cell population.

Core Technologies and Workflows: CRISPR, NGS, and Multi-Omics Integration

Gene editing and perturbation tools are foundational to modern functional genomics research, enabling scientists to dissect gene function, model diseases, and develop novel therapeutic strategies. These technologies have evolved from early gene silencing methods to sophisticated systems capable of making precise, targeted changes to the genome. Within the context of functional genomics, these tools allow for the systematic interrogation of gene function on a genome-wide scale, accelerating the identification and validation of drug targets. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core technologies—CRISPR-Cas9, base editing, and RNA interference (RNAi)—detailing their mechanisms, applications, and experimental protocols for a scientific audience engaged in drug development and basic research.

CRISPR-Cas9

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, derived from a bacterial adaptive immune system, has become the most widely adopted genome-editing platform due to its simplicity, efficiency, and versatility [28] [29]. The system functions as a RNA-guided DNA endonuclease. The core components include a Cas9 nuclease and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that is composed of a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) sequence, which confers genomic targeting through complementary base pairing, and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) scaffold that recruits the Cas9 nuclease [28] [30]. Upon sgRNA binding to the complementary DNA sequence adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), typically a 5'-NGG-3' sequence for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the Cas9 nuclease induces a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA [29].

The cellular repair of this DSB determines the editing outcome. The dominant repair pathway, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), is error-prone and often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function by causing frameshift mutations or premature stop codons [30]. The less frequent pathway, homology-directed repair (HDR), can be harnessed to introduce precise genetic modifications, but requires a DNA repair template and is restricted to specific cell cycle phases [29].

Base Editing

Base editing represents a significant advancement in precision genome editing, enabling the direct, irreversible chemical conversion of one DNA base pair into another without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates [31] [32]. Base editors are fusion proteins that consist of a catalytically impaired Cas9 nuclease (nCas9), which creates a single-strand break, tethered to a DNA-modifying enzyme [31] [33]. Two primary classes of base editors have been developed:

- Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) catalyze the conversion of a C•G base pair to a T•A base pair. They use cytidine deaminase enzymes (e.g., from the APOBEC family) to deaminate cytidine to uridine within a small editing window (typically positions 4-8 within the protospacer) [31] [32]. The subsequent DNA mismatch repair machinery then fixes this change.

- Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) catalyze the conversion of an A•T base pair to a G•C base pair. They use engineered tRNA adenosine deaminases (e.g., TadA) to deaminate adenine to inosine [31] [32].

A key advantage of base editing is the reduction of undesirable indels that are common with standard CRISPR-Cas9 editing [32] [33]. Its primary limitation is the restriction to transition mutations (purine to purine or pyrimidine to pyrimidine) rather than transversions [31].

RNA Interference (RNAi)

RNA interference (RNAi) is a conserved biological pathway for sequence-specific post-transcriptional gene silencing [34]. It utilizes small double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules, approximately 21-22 base pairs in length, to guide the degradation of complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences. The two primary synthetic RNAi triggers used in research are:

- Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs): These are synthetic 21-22 bp dsRNAs with 2-nucleotide 3' overhangs. They are pre-loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Within RISC, the "passenger" strand is cleaved and discarded, while the "guide" strand directs RISC to complementary mRNA targets for endonucleolytic cleavage by Argonaute 2 (Ago2) [34].

- Short Hairpin RNAs (shRNAs): These are DNA-encoded RNA molecules that fold into a stem-loop structure. They are transcribed in the nucleus and exported to the cytoplasm, where they are processed by the enzyme Dicer into siRNA-like molecules that subsequently enter the RISC pathway [34]. shRNAs enable long-term, stable gene silencing through viral integration.

The major advantage of RNAi is its potency and specificity for knocking down gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. However, it is primarily a tool for loss-of-function studies and can have off-target effects due to partial complementarity with non-target mRNAs [34] [35].

Quantitative Technology Comparison

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and performance metrics of CRISPR-Cas9, base editing, and RNAi technologies, providing a direct comparison to inform experimental design.

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics and applications of gene editing tools.

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | Base Editing | RNAi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | RNA-guided DNA endonuclease creates DSBs [29] | Catalytically impaired Cas9 fused to deaminase; single-base chemical conversion [31] [32] | siRNA/shRNA guides mRNA cleavage via RISC [34] |

| Genetic Outcome | Gene knockouts (via indels) or knock-ins (via HDR) [29] [30] | Single nucleotide substitutions (C>T or A>G) [31] [33] | Transient or stable gene knockdown (mRNA degradation) [34] |

| Key Components | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA [28] | nCas9-deaminase fusion, sgRNA [31] | siRNA (synthetic) or shRNA (expressed) [34] |

| Delivery Methods | Plasmid DNA, RNA, ribonucleoprotein (RNP); viral vectors [29] | Plasmid DNA, mRNA, RNP; viral vectors [31] | Lipid nanoparticles (siRNA); viral vectors (shRNA) [34] |

| Primary Applications | Functional gene knockouts, large deletions, gene insertion, disease modeling [28] [29] | Pathogenic SNP correction, disease modeling, introducing precise point mutations [31] [33] | High-throughput screens, transient gene knockdown, therapeutic target validation [34] |

| Typical Editing Efficiency | Highly variable; can reach >70% in easily transfected cells [30] | Variable (10-50%); can exceed 90% in optimized systems [31] | Variable; ~60-80% mRNA knockdown is common [35] |

Table 2: Performance metrics and practical considerations for research use.

| Consideration | CRISPR-Cas9 | Base Editing | RNAi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Moderate to high; subject to off-target indels [29] | High for single-base changes; potential for "bystander" editing within window [31] [32] | High on-target, but seed-based off-targets are common [34] [35] |

| Scalability | Excellent for high-throughput screening [29] | Moderate; improving for screening applications | Excellent for high-throughput screening [34] |

| Ease of Use | Simple sgRNA design and cloning [29] | Simple sgRNA design; target base must be within activity window [31] | Simple siRNA design; algorithms predict effective sequences [34] |

| Cost | Low (relative to ZFNs/TALENs) [29] | Moderate to low | Low for siRNA; moderate for viral shRNA |

| Throughput | High (enables genome-wide libraries) [19] | Moderate to high | High (enables genome-wide libraries) [34] |

| Key Limitations | Off-target effects, PAM requirement, HDR inefficiency [29] | Restricted to transition mutations, limited editing window, PAM requirement [31] [32] | Transient effect (siRNA), potential for immune activation, compensatory effects [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CRISPR-Cas9 Protocol for Gene Knockout

The following protocol details the steps for generating a gene knockout in cultured cells using CRISPR-Cas9, based on methodologies successfully applied in chicken primordial germ cells (PGCs) and other systems [30].

1. gRNA Design and Cloning:

- Target Selection: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence within an early exon of the gene of interest. The sequence must be directly 5' of an NGG PAM sequence.

- Specificity Check: Use tools like BLAST or specialized CRISPR design software to ensure minimal off-target binding in the relevant genome.

- Oligonucleotide Annealing: Synthesize and anneal complementary oligonucleotides encoding the target sequence.

- Plasmid Ligation: Clone the annealed oligonucleotides into a CRISPR plasmid vector expressing both the sgRNA and the Cas9 nuclease (e.g., px330). Verify the construct by Sanger sequencing.

2. Cell Transfection and Selection:

- Delivery: Transfect the CRISPR plasmid into the target cells using an appropriate method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection). A puromycin resistance marker on the plasmid can be used for selection. As reported in a study on chicken PGCs, transfection efficiency can be critical, and high-fidelity Cas9 variants have shown higher deletion efficiency (69%) compared to wildtype Cas9 (29%) in some contexts [30].

- Selection: Treat cells with the appropriate selection antibiotic (e.g., 1-2 µg/mL puromycin) for 48-72 hours post-transfection to enrich for successfully transfected cells.

3. Analysis of Editing Efficiency:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 3-5 days post-transfection and isolate genomic DNA.

- Target Amplification: Perform PCR using primers flanking the genomic target site.

- Mutation Detection:

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay: Hybridize the PCR products, digest with T7EI (which cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA), and analyze the cleavage pattern by gel electrophoresis [30].

- Digital PCR (dPCR): For absolute quantification of deletion efficiency, use a dPCR assay with probes specific for the wildtype and deleted alleles. This method is highly sensitive and allows for the detection of low-frequency editing events [30].

4. Clonal Isolation and Validation:

- Single-Cell Sorting: Dilute the transfected cell population to a density of ~1 cell/100 µL and plate into 96-well plates.

- Clone Expansion: Culture the cells for 2-3 weeks to allow clonal expansion.

- Genotyping: Screen expanded clones by PCR and Sanger sequencing to identify clones with homozygous frameshift mutations.

Base Editing Experimental Workflow

This protocol outlines the key steps for implementing a base editing experiment in mammalian cells, incorporating optimization strategies from recent literature [31] [32].

1. sgRNA Design for Base Editing:

- Window Positioning: Design sgRNAs such that the target base (C for CBEs, A for ABEs) is located within the effective editing window of the base editor (typically positions 4-8 for original BE3 and ABE7.10 systems). Note that newer variants may have altered windows [31].

- Bystander Analysis: Check the protospacer sequence for additional editable bases (other C or A nucleotides) within the activity window, as these may undergo concurrent, potentially undesired "bystander" editing [32].

- Specificity and PAM: Perform standard specificity checks and ensure the presence of a compatible PAM. For targets with non-NGG PAMs, consider using Cas9 variants like xCas9 or SpCas9-NG, though their activity with base editors may require empirical testing [31].

2. Base Editor Delivery:

- Plasmid Transfection: Co-transfect the base editor expression plasmid (e.g., BE4 for CBE, ABE7.10 for ABE) and the sgRNA expression plasmid into the target cells.

- Optimized Constructs: For higher efficiency, consider using codon-optimized base editors with enhanced nuclear localization signals (NLS), such as bipartite NLSs, which have been shown to significantly increase editing rates [31].

3. Validation and Analysis:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 3-7 days post-transfection.

- Targeted Sequencing: Amplify the target region by PCR and subject the product to Sanger sequencing or, for a more quantitative assessment, next-generation sequencing (NGS). NGS allows for precise quantification of editing efficiency and the detection of bystander edits and low-frequency indels [31] [32].

- Functional Assay: Where possible, couple genotypic validation with a phenotypic assay to confirm the functional consequence of the base edit (e.g., altered protein function, drug resistance).

RNAi Knockdown Protocol

This protocol describes gene silencing using synthetic siRNAs, a common approach for transient knockdown, and touches on shRNA strategies for stable silencing [34].

1. siRNA Design and Selection:

- Algorithmic Design: Use established design rules, which often favor siRNAs with asymmetric thermodynamic stability of the duplex ends (weaker binding at the 5' end of the antisense strand) to promote proper RISC loading [34].

- Validation: Whenever possible, select multiple (e.g., 3-4) pre-validated siRNAs targeting different regions of the same mRNA from commercial vendors to control for sequence-specific efficacy and off-target effects.

2. Cell Transfection and Optimization:

- Reverse Transfection: Plate cells and transfer siRNAs simultaneously to increase efficiency. Complex the siRNAs with a lipid-based transfection reagent optimized for RNAi.

- Dose Titration: Perform a dose-response experiment (typically 1-50 nM final siRNA concentration) to determine the optimal concentration that maximizes knockdown while minimizing cytotoxicity and off-target effects.

- Controls: Include both a negative control siRNA (scrambled sequence) and a positive control siRNA (targeting a constitutively expressed gene) in every experiment.

3. Efficiency Validation:

- Time Course: Analyze knockdown efficiency 48-96 hours post-transfection, as the peak effect is often observed within this window.

- qRT-PCR: Isolve total RNA and perform quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to measure the reduction in target mRNA levels. A fold change (FC) of 0.5 (i.e., 50% knockdown) or lower is often considered successful, though efficiency varies by cell line and target [35].

- Western Blotting: If a suitable antibody is available, confirm the knockdown at the protein level 72-96 hours post-transfection. Studies have shown that validation by Western blot often correlates with higher observed silencing efficiency [35].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools for implementing the gene editing and perturbation technologies discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Key research reagents and resources for gene perturbation experiments.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Plasmids | Express Cas9 and sgRNA from a single vector for convenient delivery. | px330, lentiCRISPR v2. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Reduce off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity. | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1 [30]. |

| Base Editor Plasmids | All-in-one vectors for cytosine or adenine base editing. | BE4 (CBE), ABE7.10 (ABE) [31] [32]. |

| Synthetic siRNAs | Pre-designed, chemically modified duplex RNAs for transient knockdown. | ON-TARGETplus (Dharmacon), Silencer Select (Ambion); chemical modifications (2'F, 2'O-Me) enhance stability [34]. |

| shRNA Expression Vectors | DNA templates for long-term, stable gene silencing via viral delivery. | pLKO.1 (lentiviral); part of genome-wide libraries [34]. |

| Transfection Reagents | Facilitate intracellular delivery of nucleic acids. | Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX (for RNP), Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (for siRNA), electroporation systems [34] [30]. |

| Editing Validation Kits | Detect and quantify nuclease-induced mutations. | T7 Endonuclease I Kit (for indels), Digital PCR Assays (for absolute quantification) [30]. |

| Genome-Wide Libraries | Collections of pre-cloned guides/shRNAs for high-throughput functional genomics screens. | CRISPRko libraries (e.g., Brunello), shRNA libraries (e.g., TRC), RNAi consortium collections [34] [19]. |

| Alignment & Design Tools | Bioinformatics platforms for designing and validating guide RNAs or siRNAs against current genome builds. | CRISPOR, DESKGEN; tools must be continuously reannotated against updated genome assemblies (e.g., GRCh38) for accuracy [9]. |

CRISPR-Cas9, base editing, and RNAi constitute a powerful toolkit for functional genomics and drug discovery research. CRISPR-Cas9 excels at generating complete gene knockouts and larger structural variations. Base editing offers superior precision for modeling and correcting point mutations with fewer genotoxic byproducts. RNAi remains a rapid and cost-effective solution for transient gene knockdown and high-throughput screening. The choice of technology depends critically on the experimental question, desired genetic outcome, and model system. As these tools continue to evolve—with improvements in specificity, efficiency, and delivery—their integration with multi-omics data and advanced analytics will further solidify their role in deconvoluting biological complexity and accelerating therapeutic development.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, bringing about a paradigm shift in how scientists analyze DNA and RNA molecules. This transformative technology provides unparalleled capabilities for high-throughput, cost-effective analysis of genetic information, swiftly propelling advancements across diverse genomic domains [36]. NGS allows for the simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, delivering comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [36]. The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of genomics research, facilitating critical studies on rare genetic diseases, cancer genomics, microbiome analysis, infectious diseases, and population genetics [36].

The evolution of sequencing technologies has progressed rapidly over the past two decades, leading to the emergence of three distinct generations of sequencing methods. First-generation sequencing, pioneered by Sanger's chain-termination method, enabled the production of sequence reads up to a few hundred nucleotides and was instrumental in early genomic breakthroughs [36]. The advent of second-generation sequencing methods revolutionized DNA sequencing by enabling massive parallel sequencing of thousands to millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, dramatically increasing throughput and reducing costs [36]. Third-generation technologies further advanced the field by offering long-read sequencing capabilities that bypass PCR amplification, enabling the direct sequencing of single DNA molecules [36].

NGS Technology Platforms and Market Landscape

Current NGS Platforms and Technologies

The contemporary NGS landscape features a diverse array of platforms employing different sequencing chemistries, each with distinct advantages and limitations. These technologies can be broadly categorized into short-read and long-read sequencing platforms, with ongoing innovation continuously pushing the boundaries of what's possible in genomic analysis [36] [37].

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms and Technologies

| Platform | Sequencing Technology | Read Length | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) with reversible dye-terminators | 36-300 bp (short-read) | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, targeted sequencing | Potential signal overcrowding; ~1% error rate [36] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing (detects H+ ions) | 200-400 bp (short-read) | Whole genome sequencing, targeted sequencing | Homopolymer sequence errors [36] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp (long-read) | De novo genome assembly, full-length transcript sequencing | Higher cost per sample [36] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing (electrical impedance detection) | 10,000-30,000 bp (long-read) | Real-time sequencing, field applications | Error rates can reach 15% [36] |

| Roche 454 | Pyrosequencing | 400-1,000 bp | Amplicon sequencing, metagenomics | Inefficient homopolymer determination [36] |

The global NGS market reflects the growing adoption and importance of these technologies, with the market size calculated at US$10.27 billion in 2024 and projected to reach approximately US$73.47 billion by 2034, expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.74% [38]. This growth is driven by applications in disease diagnosis, particularly in oncology, and the increasing integration of NGS in clinical and research settings [38].

Emerging Sequencing Technologies

The NGS landscape continues to evolve with the introduction of novel sequencing approaches. Roche's recently unveiled Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology represents a promising new category of NGS that addresses fundamental limitations of existing methods [39] [40]. SBX employs a sophisticated biochemical process that encodes the sequence of target nucleic acids into a measurable surrogate polymer called an Xpandomer, which is fifty times longer than the original molecule [40]. These Xpandomers encode sequence information into high signal-to-noise reporters, enabling highly accurate single-molecule nanopore sequencing with a CMOS-based sensor module [39]. This approach allows hundreds of millions of bases to be accurately detected every second, potentially reducing the time from sample to genome from days to hours [40].

RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Experimental Design

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has transformed transcriptomic research by enabling large-scale inspection of mRNA levels in living cells, providing comprehensive insights into gene expression profiles under various biological conditions [41]. This powerful technique allows researchers to quantify transcript abundance, identify novel transcripts, detect alternative splicing events, and characterize genetic variation in transcribed regions [42]. The growing applicability of RNA-Seq to diverse scientific investigations has made the analysis of NGS data an essential skill, though it remains challenging for researchers without bioinformatics backgrounds [41].

Proper experimental design is crucial for successful RNA-Seq studies. Best practices include careful consideration of controls and replicates, as these decisions can significantly impact experimental outcomes [42]. Two primary RNA sequencing approaches are commonly employed: whole transcriptome sequencing and 3' mRNA sequencing [42]. Whole transcriptome sequencing provides comprehensive coverage of transcripts, enabling the detection of alternative splicing events and novel transcripts, while 3' mRNA sequencing offers a more focused approach that is particularly efficient for gene expression quantification in large sample sets [42].

RNA-Seq Workflow and Data Analysis

The RNA-Seq workflow encompasses both laboratory procedures (wet lab) and computational analysis (dry lab). The process begins with sample collection and storage, followed by RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing [43] [41]. Computational analysis typically starts with quality assessment of raw sequencing data (.fastq files) using tools like FastQC, followed by read trimming to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases with programs such as Trimmomatic [41]. Quality-controlled reads are then aligned to a reference genome using spliced aligners like HISAT2, after which gene counts are quantified to generate expression matrices [41].

RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow