Optimizing Functional Genomics Screening Libraries: Strategies for Enhanced Target Discovery in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing functional genomics screening libraries.

Optimizing Functional Genomics Screening Libraries: Strategies for Enhanced Target Discovery in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing functional genomics screening libraries. It covers foundational principles of library design, explores advanced methodological applications like CRISPR-Cas and RNAi, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges in data management and computational analysis, and establishes robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing current technologies and emerging trends such as AI integration and single-cell analysis, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency, reliability, and translational impact of functional genomics screens for accelerated therapeutic discovery.

Core Principles and Evolving Landscape of Screening Libraries

Core Concepts: Forward vs. Reverse Genetics

What is the fundamental difference between forward and reverse genetics?

In functional genomics, forward genetics and reverse genetics represent two distinct pathways for linking genes to their biological functions.

Forward Genetics: This is a phenotype-driven approach. Research begins with an observable trait or phenotype, and the goal is to identify the underlying genetic sequence responsible for it. This often involves screening populations with random genomic mutations to find which mutation causes the phenotype of interest, followed by mapping and sequencing the causative gene [1] [2].

Reverse Genetics: This is a gene-driven approach. Research starts with a known gene sequence, and the goal is to determine its function by deliberately disrupting or modifying the gene and then observing the resulting phenotypic changes [2].

The following workflow illustrates the contrasting paths of these two methodologies:

FAQs: Functional Genomics Screening

What are the main types of functional genomics screening libraries?

Several library types are available, each with distinct advantages and considerations for high-throughput screening [3]:

| Library Type | Key Features | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA | Transient knockdown; resuspension in buffer; delivery via transfection; peak silencing at 48-72 hours [3]. | Short-term knockdown in easy-to-transfect cells [3]. |

| shRNA (Plasmid) | Supplied as transformed E. coli; renewable resource; requires plasmid prep; transient silencing [3]. | Knockdown when a renewable reagent source is needed [3]. |

| shRNA/sgRNA (Pooled Lentiviral) | Pooled delivery; enables stable integration; suitable for primary and non-dividing cells; allows for selection strategies [3]. | Long-term silencing/knockout in diverse cell types, including in vivo screens [3]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA | Versatile, high knockout efficiency, less off-target effect compared to other technologies. It has become the preferred platform for large-scale gene function screening [4] [3]. | Genome-wide knockout, activation, or inhibition screens [4] [3]. |

How do I know if my CRISPR screen was successful?

The most reliable method is to include well-validated positive-control genes and their corresponding sgRNAs in your library. A successful screen will show these controls being significantly enriched or depleted in the expected direction. If such controls are not available, you can assess screening performance by examining the degree of cellular response to selection pressure and analyzing the distribution and log-fold change of sgRNA abundance in bioinformatics outputs [4].

Why might different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance?

Gene editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence. It is common for different sgRNAs against the same gene to have substantial variability in their editing efficiency. To ensure robust results, it is recommended to design at least 3-4 sgRNAs per gene to mitigate the impact of this variability [4].

Is a low mapping rate in NGS data a concern for CRISPR screen reliability?

A low mapping rate itself typically does not compromise the reliability of your results, as downstream analysis focuses only on the reads that successfully map to the sgRNA library. The critical factor is to ensure that the absolute number of mapped reads is sufficient to maintain a recommended sequencing depth of at least 200x coverage. Insufficient data volume is a more common source of variability and reduced accuracy than a low mapping rate percentage [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting CRISPR Screening Data Analysis

The table below outlines common issues encountered during CRISPR screen data analysis and their potential solutions [4].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No significant gene enrichment | Insufficient selection pressure during screening [4]. | Increase selection pressure and/or extend the screening duration [4]. |

| Large loss of sgRNAs in sample | Pre-screening: Insufficient initial sgRNA representation [4]. Post-screening: Excessive selection pressure [4]. | Re-establish library cell pool with adequate coverage. Re-evaluate and adjust selection pressure [4]. |

| Unexpected LFC values | Extreme values from individual sgRNAs can skew the median gene-level LFC calculated by algorithms like RRA [4]. | Interpret LFC in the context of the RRA score and the performance of all sgRNAs for a gene [4]. |

| High false positives/negatives in FACS-based screens | Often allows only a single round of enrichment, increasing technical noise [4]. | Increase the initial number of cells and perform multiple rounds of sorting where feasible [4]. |

| Low reproducibility between replicates | Technical variability or low signal-to-noise ratio [4]. | If Pearson correlation is >0.8, analyze replicates together. If low, perform pairwise comparisons and identify overlapping hits (e.g., via Venn diagrams) [4]. |

Troubleshooting Sequencing Library Preparation

Problems during Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library preparation can compromise screening data. Here are frequent issues and their diagnostics [5].

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Low yield; smear in electropherogram; low complexity [5]. | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [5]. |

| Fragmentation / Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks [5]. | Over-/under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio [5]. |

| Amplification / PCR | Over-amplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias [5]. | Too many PCR cycles; inefficient polymerase; primer exhaustion or mispriming [5]. |

| Purification / Cleanup | Incomplete removal of small fragments; sample loss; carryover of salts [5]. | Wrong bead ratio; over-drying beads; inefficient washing; pipetting error [5]. |

The following decision tree can help diagnose a failed sequencing reaction:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful functional genomics screen relies on a suite of well-validated reagents and tools. The table below details essential components and their functions.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Screening | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR gRNA Library | Guides Cas9 nuclease to specific genomic loci to create knockouts. The cornerstone of modern functional genomic screens [4] [3]. | Design includes 3-4 sgRNAs/gene for robustness. Must be reannotated against latest genome builds to maintain accuracy [4] [6]. |

| Lentiviral Delivery System | Efficiently delivers genetic material (e.g., sgRNAs, shRNAs) into a wide range of cells, including primary and non-dividing cells, enabling stable integration [3]. | Pooled formats are standard for high-throughput screens. Requires careful titer control [3]. |

| RNAi (siRNA/shRNA) Libraries | Mediates transient (siRNA) or stable (shRNA) gene knockdown at the mRNA level via the RNA interference pathway [3]. | shRNA in lentiviral vectors is ideal for long-term effects. siRNA is suitable for short-term knockdown in transferable cells [3]. |

| Analysis Software (MAGeCK) | A widely used computational tool for analyzing CRISPR screening data. It identifies positively and negatively selected genes from sgRNA read counts [4]. | Incorporates RRA (for single-condition) and MLE (for multi-condition) algorithms for robust statistical analysis [4]. |

| Positive Control sgRNAs | Target genes known to produce a strong phenotype (e.g., essential genes). They are included in the library to validate screening conditions [4]. | Critical for confirming that the screen worked. Their significant enrichment/depletion indicates successful selection [4]. |

| GX-674 | GX-674 is a highly selective Nav1.7 antagonist for pain and cancer metastasis research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human use. | |

| HTMT dimaleate | HTMT dimaleate, MF:C27H33F3N4O9, MW:614.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols & Best Practices

Ensuring Genomic Reagent Accuracy: Reannotation and Realignment

The genomic landscape is continuously evolving with improved sequencing technologies and annotations. To ensure functional genomics tools remain accurate, two processes are critical [6]:

- Reannotation: The process of remapping existing sgRNA or RNAi reagent sequences against the latest genome references (e.g., NCBI RefSeq). This ensures that the annotations for your reagents reflect current knowledge without changing the reagents themselves [6].

- Realignment: A more in-depth process that involves redesigning reagents using advanced bioinformatics and the most recent genomic insights. This can improve coverage of important gene variants and isoforms and reduce off-target effects caused by previously inaccurate genomic data [6].

Best Practice: When starting a new project, ensure you are using reagents that have undergone recent realignment or reannotation to maximize target coverage and experimental relevance [6].

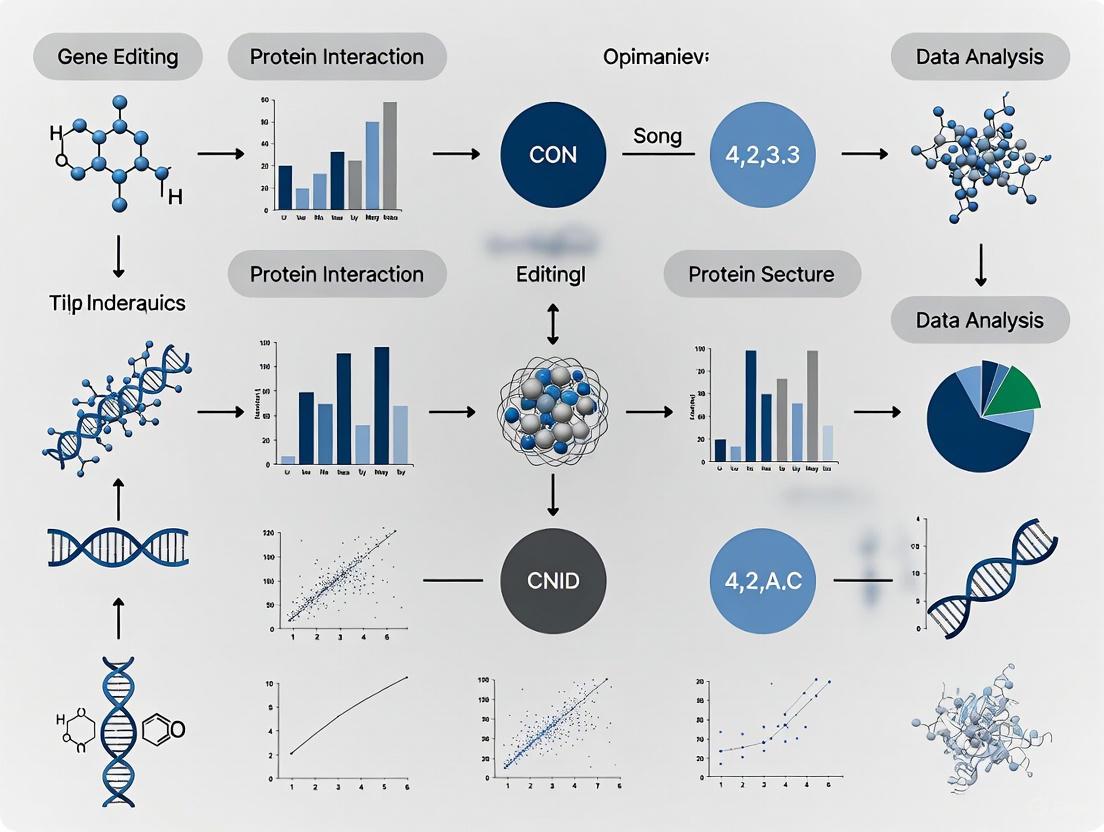

A General Workflow for High-Throughput Functional Genomics Screening

The diagram below outlines a standardized workflow for a high-throughput screening campaign, integrating both experimental and computational steps.

In the field of functional genomics, CRISPR screening has become an indispensable method for identifying gene functions and potential therapeutic targets. The two primary formats for these screens—pooled and arrayed—each offer distinct advantages and present unique challenges. Selecting the appropriate format is crucial for the success of a screening campaign and depends heavily on the specific research question, the biological model, the phenotypic readout, and available resources. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two fundamental approaches, offering troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols to help researchers optimize their functional genomics studies.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Selection Guidance

What is the fundamental difference between pooled and arrayed CRISPR screens?

The core difference lies in how the genetic perturbations are delivered and analyzed.

Pooled Screening: A mixture (pool) of guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting all genes of interest is delivered simultaneously to a single population of cells. The gRNAs are typically delivered via lentiviral vectors, which integrate into the host genome, allowing for the tracking of perturbations through next-generation sequencing (NGS). Deconvoluting which genetic perturbation caused a specific phenotype requires sequencing-based analysis of gRNA abundance before and after applying a selective pressure [7] [8].

Arrayed Screening: Each genetic perturbation is performed in an isolated well of a multiwell plate. Specifically, each well contains gRNAs targeting a single gene, often using multiple gRNAs per gene to enhance knockout confidence. This format directly links a genotype to a phenotype without the need for complex deconvolution, as the identity of the perturbed gene in each well is known from the outset [7] [9].

When should I choose a pooled screen over an arrayed screen?

A pooled screening format is generally the best choice under the following conditions:

- Genome-Wide Scope: Your screen aims to interrogate a very large number of genes (e.g., the entire genome) in an unbiased discovery phase [7].

- Simple, Selectable Phenotype: Your primary readout is a simple, binary phenotype that allows for the physical separation or selective enrichment/depletion of cell populations. Classic examples include:

- Resource Constraints: You have limited budget for upfront costs and lack access to high-throughput automation equipment for liquid handling and phenotypic analysis. Pooled screens require standard cell culture equipment and are more cost-effective for large-scale screens [10] [8].

What are the key advantages of arrayed screens that would justify their higher cost and complexity?

Arrayed screens provide several critical advantages that are essential for more complex biological questions:

- Complex Phenotypic Readouts: They are compatible with high-content and multiparametric assays. This includes detailed morphological analysis via microscopy, measurements of electrophysiological properties, and analysis of extracellular secretion [7] [8].

- Direct Genotype-Phenotype Link: Because each gene is targeted in a separate well, there is no need for NGS-based deconvolution. The phenotype measured in a well can be directly attributed to the known gene being targeted [8].

- Study of Complex Cellular Models: They are better suited for use with sensitive cell types like primary cells and neurons, which may not tolerate the lentiviral integration and extended expansion required in pooled screens [10] [8].

- Safety and Precision: Arrayed screens often use synthetic ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), avoiding the use of lentiviral vectors and their associated biosafety concerns. The RNP approach also prevents genomic integration of screening reagents, reducing potential confounding factors [7].

Can these screening approaches be used in combination?

Yes, a powerful and common strategy is to use both formats in a tiered screening workflow.

- Primary Screen (Pooled): A genome-wide pooled screen is conducted to identify a broad list of "hit" genes involved in a selectable phenotype (e.g., survival under drug treatment).

- Secondary Validation Screen (Arrayed): The hits from the primary screen are then validated using a targeted, arrayed screen. This confirms the findings in a more controlled setting and allows for deeper, more complex phenotypic analysis on the validated subset of genes [7] [8].

Table: Key Considerations for Choosing a Screening Format

| Factor | Pooled Screening | Arrayed Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Library Scale | Ideal for large, genome-wide libraries [7] | Ideal for focused, targeted libraries [7] |

| Phenotype Complexity | Simple, selectable phenotypes (e.g., viability) [8] | Complex, multiparametric phenotypes (e.g., morphology) [7] [8] |

| Cell Model | Best for robust, immortalized cell lines [8] | Suitable for primary cells and neurons [10] [8] |

| Equipment Needs | Standard cell culture equipment [10] | High-throughput automation, liquid handlers [10] |

| Data Analysis | Requires NGS and bioinformatics [8] | Direct correlation; often simpler analysis [8] |

| Upfront Cost | Lower [8] | Higher [8] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Gene Knockout Efficiency in Arrayed Screens

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Low Transfection Efficiency.

- Solution: Optimize transfection protocols for your specific cell line. Consider using electroporation systems (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector System) for higher efficiency, especially with RNP complexes [7]. Always include a fluorescent control to monitor efficiency.

- Cause: Ineffective gRNA Design.

- Solution: Use a qgRNA (quadruple-guide RNA) strategy. Targeting a single gene with four different gRNAs in the same well dramatically increases the probability of a complete knockout compared to a single gRNA [12]. Ensure your gRNA designs are based on the most current genome annotations to avoid targeting outdated sequences [6].

Issue 2: High False Positive/Negative Rates in Pooled Screens

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Library Coverage.

- Solution: Ensure you use a sufficient number of cells during transduction to maintain library diversity. A common guideline is to use 200-1000 cells per gRNA in your library to prevent stochastic loss of guides [8].

- Solution: Transduce cells at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI ~0.3) to minimize the chance of a single cell receiving multiple gRNAs, which can complicate data interpretation [8].

- Cause: Off-Target Effects.

- Solution: Design gRNAs with high on-target specificity using modern algorithms. For any hit, confirm the phenotype using multiple, independent gRNAs targeting the same gene in a follow-up arrayed validation experiment [7].

Issue 3: Confounding Paracrine Effects in Pooled Screens

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: In a pooled culture, a cell with one gene knockout may secrete factors (e.g., inducing inflammation or senescence) that affect the growth or phenotype of neighboring cells with different knockouts. This "bystander effect" can lead to the misattribution of a phenotype [7].

- Solution: If your screen involves phenotypes where cell-cell signaling is a concern, an arrayed format is superior. In an arrayed screen, all cells in a well have the same knockout, so any paracrine effects are confined to that well and can still be correctly linked to the targeted gene [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Workflow for a Pooled CRISPR Knockout Screen

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing a pooled viability screen to identify genes essential for cell survival or drug response.

Detailed Methodology:

Library Construction:

- Begin with a pooled plasmid library as an E. coli glycerol stock. Amplify the plasmid library and prepare maxipreps. Validate the library representation by NGS to ensure all gRNAs are present at roughly equal abundance [8].

- Package the sgRNA plasmids into lentiviral particles. Purify and titer the virus to determine the concentration.

Cell Transduction & Selection:

- Transduce your Cas9-expressing cell line with the lentiviral library at a low MOI (e.g., ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one gRNA. Include a selection marker (e.g., puromycin) in the library vector.

- 24 hours post-transduction, add puromycin to the culture media to select for successfully transduced cells. Maintain the culture for several days to allow for gene editing and turnover of the target protein.

Apply Selective Pressure & Analysis:

- Split the cell population into two groups: a reference control (harvested at the start of selection) and the experimental group. For a negative selection screen (e.g., essential genes), passage the experimental group for 2-3 weeks without any pressure; cells with essential genes knocked out will drop out. For a positive selection screen (e.g., drug resistance), treat the experimental group with the drug for a defined period [8].

- Harvest genomic DNA from both the reference control and the final experimental cell population.

- Use PCR to amplify the integrated gRNA sequences from the genomic DNA. These amplicons are then subjected to NGS.

- Bioinformatically count the frequency of each gRNA in the pre- and post-selection samples. gRNAs that are significantly depleted (in a negative screen) or enriched (in a positive screen) identify genes involved in the phenotype [8] [11].

Protocol 2: Workflow for an Arrayed CRISPR Screen Using Synthetic RNPs

This protocol describes a high-throughput arrayed screen using synthetic gRNAs complexed with Cas9 protein (RNP), a method favored for its efficiency and safety.

Detailed Methodology:

Plate Setup and RNP Formation:

- Obtain a custom synthetic gRNA library pre-dispensed into 384-well plates. For increased robustness, use a qgRNA format where each well contains a mix of four gRNAs targeting the same gene [12].

- In each well, complex the gRNAs with recombinant Cas9 protein to form ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) in a buffer suitable for your delivery method.

Delivery to Cells:

- Seed Cas9-expressing cells or wild-type cells directly into the wells containing the pre-formed RNPs. For efficient delivery, especially in hard-to-transfect cells, use an electroporation-based system like the Lonza 4D-Nucleofector with a 384-well shuttle attachment [7].

- Incubate the cells for a sufficient duration to allow for gene editing and the manifestation of the phenotype (typically 3-7 days).

Phenotypic Assay and Analysis:

- Apply your assay to measure the phenotype. This could be a high-content imaging assay for morphology, a FACS-based assay for surface markers, an ELISA for secreted factors, or treatment with a drug to measure viability [9].

- Since each well corresponds to a single gene target, data analysis involves comparing the phenotypic readout of each test well to control wells (e.g., non-targeting gRNAs). Statistical analysis (e.g., Z-score calculation) identifies significant hits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for CRISPR Screening

| Item | Function in Screening | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| crRNA/tracrRNA (2-part) | Synthetic guide RNA components that anneal to form the functional gRNA. | Often used in arrayed RNP screens for high editing efficiency and low off-target effects [9]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Vehicle for stable integration of gRNA constructs into the host cell genome. | Essential for pooled screens; requires biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) precautions [8]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and gRNA. | Used in arrayed screens; enables rapid, high-efficiency editing without genomic integration [7]. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cell Line | A cell line engineered to stably express the Cas9 nuclease. | Simplifies screen execution; required if gRNA delivery vector does not encode Cas9. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Robotics for dispensing nanoliter volumes in 384/1536-well plates. | Critical for high-throughput arrayed screens to ensure accuracy and reproducibility [10]. |

| High-Content Imager | Automated microscope for capturing multiparametric image-based data. | Enables complex phenotypic readouts in arrayed screens (morphology, cell count, etc.) [8]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencer | Platform for deep sequencing of gRNA amplicons. | Required for the final readout and deconvolution of pooled screens [8]. |

| Hydroxy-PEG2-acid | Hydroxy-PEG2-acid, MF:C7H14O5, MW:178.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Iberdomide | Iberdomide (CC-220)|CELMoD|CRBN E3 Ligase Modulator | Iberdomide is a potent, novel cereblon E3 ligase modulator (CELMoD) for cancer and autoimmune disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The evolution from RNA interference (RNAi) to CRISPR-Cas systems represents a paradigm shift in functional genomics research. For scientists engaged in high-throughput screening to identify gene function, this transition offers new possibilities alongside unique challenges. RNAi, the established method for gene knockdown, utilizes the cell's natural RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to degrade target messenger RNA (mRNA), resulting in reduced gene expression [13] [14]. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas systems achieve permanent gene knockout by creating double-strand breaks in DNA that are repaired through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often resulting in frameshift mutations and complete loss of gene function [13] [14]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and FAQs to help researchers optimize their functional genomics screening strategies within this evolving technological landscape.

Technology Comparison: RNAi vs. CRISPR-Cas

Core Mechanisms and Applications

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between RNAi and CRISPR-Cas Technologies

| Feature | RNAi (Knockdown) | CRISPR-Cas (Knockout) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Post-transcriptional gene silencing via mRNA degradation or translational inhibition [13] | DNA-level gene editing via double-strand breaks and error-prone repair [13] |

| Target Molecule | mRNA [13] [14] | Genomic DNA [13] [14] |

| Effect on Gene Expression | Partial reduction (knockdown) [14] | Complete and permanent silencing (knockout) [14] |

| Key Components | siRNA, shRNA, Dicer, RISC complex [13] | Guide RNA (gRNA/sgRNA), Cas nuclease [13] |

| Typical Efficiency | Variable; 70-90% protein reduction common [13] | High; near-complete knockout achievable [13] |

| Duration of Effect | Transient (days to weeks) [3] | Permanent and heritable [13] |

| Primary Applications | Study of essential genes, transient silencing, drug target validation [13] | Complete gene ablation, functional domain mapping, gene therapy [13] |

Performance Characteristics in Genomic Screening

Table 2: Screening Performance Comparison Between shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9

| Performance Metric | shRNA Screening | CRISPR-Cas9 Screening | Combined Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision (AUC) | >0.90 [15] | >0.90 [15] | 0.98 [15] |

| True Positive Rate at 1% FPR | >60% [15] | >60% [15] | >85% [15] |

| Number of Genes Identified | ~3,100 [15] | ~4,500 [15] | ~4,500 [15] |

| Off-target Effects | Higher incidence, both sequence-dependent and independent [13] | Reduced with optimized guide design [13] | Mitigated through orthogonal validation |

| Biological Process Detection | Strong for: chaperonin-containing T-complex [15] | Strong for: electron transport chain [15] | Comprehensive coverage of both [15] |

| Correlation Between Technologies | Low correlation observed (R²<0.25) [15] | Low correlation observed (R²<0.25) [15] | Complementary information |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Technology Selection Guidance

Q1: When should I choose RNAi over CRISPR for my functional genomics screen?

Choose RNAi when:

- Studying essential genes where complete knockout would be lethal [13]

- Investigating gene function in systems where DNA damage response is a concern

- Seeking transient gene suppression to study reversible phenotypes [13]

- Working with genes where haploinsufficiency effects are important

- Utilizing established RNAi screening infrastructure and validation protocols

Q2: Why does my CRISPR screen identify different essential genes compared to previous RNAi screens?

This occurs because:

- CRISPR and RNAi screens show low correlation (R²<0.25) and identify distinct biological processes [15]

- CRISPR detects DNA-level essentiality while RNAi detects mRNA-level essentiality

- Technical differences include timing of effect (immediate vs. delayed) and mechanism (transcriptional vs. post-transcriptional)

- Combination of both technologies provides the most comprehensive view of gene essentiality [15]

Q3: How can I improve the accuracy of my functional genomics screens?

- Use combined analysis approaches like casTLE that integrate data from both RNAi and CRISPR screens [15]

- Implement updated genome annotations and regularly reannotate/realign your screening libraries [6]

- Employ chemically modified sgRNAs to reduce off-target effects in CRISPR screens [13]

- Utilize multiple reagents per gene to control for sequence-specific off-target effects [15]

- Validate hits with orthogonal technologies to confirm biological relevance

Technical Troubleshooting

Q4: My RNAi screen shows high off-target effects. How can I address this?

- Redesign siRNAs with improved algorithms that account for seed region effects

- Use pooled siRNA approaches with multiple constructs per gene

- Lower transfection concentrations to reduce interferon response [13]

- Implement chemical modifications to reduce sequence-independent off-target effects

- Validate findings with CRISPR to confirm on-target effects [15]

Q5: My CRISPR editing efficiency is low. What optimization steps should I take?

- Switch to ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery format for highest editing efficiency [13]

- Validate guide RNA designs using updated bioinformatics tools

- Screen multiple guide RNAs per gene to account for variability in cutting efficiency

- Optimize delivery method (lentiviral vs. synthetic guide) for your cell type

- Consider alternative Cas enzymes (Cas12a, Cas13) for specific applications [16] [17]

Q6: How do I handle genes that show conflicting results between RNAi and CRISPR screens?

- Investigate potential dosage-sensitive effects where partial knockdown vs. complete knockout produces different phenotypes

- Analyze gene expression levels, as some technologies perform better at certain expression thresholds [15]

- Consider biological context, including protein half-life and feedback mechanisms

- Use the combination of both technologies as they may reveal complementary biological insights [15]

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

High-Throughput Functional Genomics Screening Workflow

Detailed Protocol: Parallel RNAi and CRISPR Screening

Objective: Identify essential genes for cell growth using both RNAi and CRISPR technologies [15]

Materials and Reagents:

- 25 hairpin/gene shRNA library [15] OR 4 sgRNA/gene CRISPR-Cas9 library [15]

- Appropriate packaging cells (HEK293T) for lentiviral production

- Target cells (K562 or your cell line of interest)

- Selection antibiotics (puromycin for shRNA, blasticidin for Cas9)

- Nucleic acid extraction kit

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

Library Preparation and Viral Production

- For shRNA: Amplify plasmid library and produce lentiviral particles

- For CRISPR: Package sgRNA library with Cas9-containing lentivirus

- Determine viral titer for both libraries

Cell Infection and Selection

- Infect target cells at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single integration events

- Apply selection pressure (puromycin for shRNA, appropriate antibiotic for CRISPR)

- Maintain minimum coverage of 500 cells per shRNA/sgRNA

Phenotype Development

- Split cells into replicate populations at time zero

- Culture cells for 14 population doublings under standard conditions

- Passage cells regularly to maintain logarithmic growth

Sample Collection and Sequencing

- Collect genomic DNA at baseline and endpoint (day 14)

- Amplify integrated shRNA/sgRNA sequences with barcoded primers

- Sequence amplified products using next-generation sequencing

Data Analysis

- Calculate enrichment/depletion of each shRNA/sgRNA using standardized pipelines

- Apply statistical framework (e.g., casTLE) to combine data from multiple reagents [15]

- Compare hits between technologies and validate essential genes

Timeline: 4-6 weeks from library preparation to initial hit identification

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Genomics Screening

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA Libraries | siGENOME SMARTpool, ON-TARGETplus [3] | Gene knockdown in arrayed format | Chemically modified for reduced off-targets [3] |

| shRNA Libraries | GIPZ Lentiviral shRNA [3] | Stable gene knockdown | Enable long-term silencing studies [3] |

| CRISPR Knockout Libraries | 4 sgRNA/gene designs [15] | Whole-genome knockout screening | Improved coverage with multiple guides per gene [18] |

| CRISPR Modification Systems | Base editors, Prime editors [17] | Precise genome editing without double-strand breaks | Reduced genomic disruption [17] |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral particles, synthetic sgRNA [13] | Efficient reagent delivery | RNP format provides highest editing efficiency [13] |

| Validation Tools | CRISPR Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit [14] | Edit confirmation | Essential for verifying knockout efficiency |

| Specialized Cas Enzymes | Cas12a, Cas13, Cas7-11 [16] [17] | Expanded targeting capabilities | RNA targeting (Cas13), multiplex editing (Cas12a) [16] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of functional genomics continues to evolve with several emerging technologies:

Novel CRISPR Systems: Cas7-11 and Cas10 enzymes offer new RNA targeting capabilities [16], while hypercompact variants like CasΦ enhance delivery possibilities in constrained systems [17].

Advanced Screening Modalities: Base editing and prime editing enable precise nucleotide substitutions without double-strand breaks [17], and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) / activation (CRISPRa) systems allow reversible control of gene expression [17].

Integrated Approaches: Combination of RNAi and CRISPR screening data using statistical frameworks like casTLE provides more robust identification of essential genes [15], while multi-omics integration delivers comprehensive biological insights [19].

Improved Specificity: Continuous refinement of guide RNA designs, chemical modifications, and bioinformatic tools are progressively reducing off-target effects in both RNAi and CRISPR systems [6] [13].

Key Market Drivers and Growth Catalysts in Functional Genomics

Functional genomics is a dynamic field that bridges the gap between raw genetic information and biological meaning, employing cutting-edge computational methods and high-throughput technologies to decode complex relationships between genes, their regulation, and the traits they produce [20]. The global functional genomics market is experiencing significant growth, estimated to be valued at USD 11.34 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 28.55 billion by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.1% [21]. This expansion is primarily driven by increasing investments in genomics research, advancements in sequencing technologies, and rising demand for personalized medicine [21]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and FAQs to help researchers optimize their functional genomics screening libraries within this rapidly evolving landscape.

Quantitative Market Segmentation

Table 1: Functional Genomics Market Share by Segment (2025 Projections)

| Segment Category | Leading Sub-segment | Market Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Product and Service | Kits and Reagents | 68.1% [21] |

| Technology | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | 32.5% [21] |

| Application | Transcriptomics | 23.4% [21] |

| Region | North America | 39.6% [21] |

Table 2: Related Market Growth Indicators

| Market | 2024 Value | 2032 Projection | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Preparation [22] | USD 1.79 Billion | USD 4.83 Billion | 13.30% |

| DNA-encoded Libraries [23] | USD 759 Million (2024) | USD 2.6 Billion (2034) | 13.5% |

Primary Market Drivers

The robust growth of the functional genomics market is catalyzed by several interconnected factors:

Technological Advancements: Continuous innovation in NGS platforms, such as Roche's Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology, enables ultra-rapid, scalable sequencing, reducing the time from sample to genome [21]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning further accelerates data analysis, guides the engineering of tools like CRISPR, and enhances the prediction of gene function and editing outcomes [20] [24].

Rising Demand for Personalized Medicine: There is a growing reliance on genomic insights to guide therapy decisions, particularly in oncology, rare genetic disorders, and infectious diseases [22]. Functional genomics is crucial for identifying disease biomarkers and developing targeted treatments, with tools like predictive clinical tests for cardiovascular disease and cancer becoming more widespread [21].

Substantial Investments and Strategic Initiatives: Governments, especially in the U.S. and EU, are increasing funding for genomics research [21]. National strategies like China’s "Made in China 2025" and India’s "Biotechnology Vision 2025" aim to build domestic genomics research capacity, fueling market expansion, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, which is the fastest-growing market [21].

Expanding Applications in Drug Discovery: Functional genomics is revolutionizing target identification and validation. Technologies like DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) allow for the high-throughput screening of billions of compounds, significantly speeding up the hit identification process in early drug discovery [23].

Troubleshooting Guides for Functional Genomics Workflows

Genomic DNA Extraction and Purification

High-quality DNA is the foundational input for reliable functional genomics data. The table below outlines common issues and solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Genomic DNA Extraction

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Incomplete cell lysis; clogged membrane; sample degradation [25]. | Thaw cell pellets on ice; cut tissue into small pieces; ensure complete Proteinase K digestion before adding lysis buffer; do not exceed recommended input amounts [25]. |

| DNA Degradation | High nuclease activity in tissues (e.g., liver, pancreas); improper sample storage [25]. | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen; store at -80°C; keep samples on ice during preparation; process tissues quickly [25]. |

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete digestion; indigestible tissue fibers clogging the column [25]. | Extend lysis time; centrifuge lysate to remove fibers before column loading; reduce input for fibrous tissues [25]. |

| Salt Contamination | Carryover of guanidine salts from the binding buffer [25]. | Avoid pipetting onto the upper column area; close caps gently to prevent splashing; perform wash steps thoroughly [25]. |

NGS Library Preparation

Library preparation is a critical step that can introduce bias and artifacts if not optimized.

Table 4: Troubleshooting NGS Library Preparation

| Problem | Common Signals | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Library Yield | Poor input quality; inaccurate quantification; inefficient fragmentation/ligation [5]. | Re-purify input DNA; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over UV; optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert ratios [5]. |

| Adapter Dimer Contamination | Sharp ~70-90 bp peak on bioanalyzer; suboptimal ligation conditions [5]. | Optimize adapter-to-insert molar ratio; use bead-based cleanup with adjusted ratios to exclude small fragments [5]. |

| High Duplication Rates | Over-amplification; low input complexity; PCR bias [5]. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; increase input DNA amount; use PCR enzymes designed for high complexity [5]. |

| Biased Coverage | Inefficient or uneven fragmentation (e.g., in GC-rich regions) [5]. | Optimize fragmentation conditions (time, energy); consider alternative enzyme-based fragmentation kits [5]. |

qPCR for Validation

qPCR is often used for target validation and requires precision.

Table 5: Troubleshooting qPCR Assays

| Issue | Potential Reasons | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Amplification | Poor sample quality, reagent degradation, incorrect primer design [26]. | Check RNA/DNA integrity; use fresh, properly stored reagents; validate primer specificity with in silico tools [26]. |

| High Ct (Cycle Threshold) Values | Low template concentration, presence of inhibitors, inefficient primers [26]. | Increase template concentration (within kit limits); re-purify sample; re-design and optimize primers [26]. |

| Non-Specific Amplification | Suboptimal annealing temperature, primer-dimer formation [26]. | Perform a temperature gradient PCR to optimize annealing; use a Hot-Start PCR kit to reduce primer-dimer artifacts [26]. |

| Inconsistent Replicates | Pipetting errors, incomplete mixing, contaminated equipment [26]. | Calibrate pipettes; prepare a master mix for all reactions; use sterile techniques and clean workspaces [26]. |

FAQs for Functional Genomics Screening

Q1: How do I decide between RNAi and CRISPR for my functional genomics screen? The choice depends on your experimental goal. CRISPR knockout (using Cas9) provides permanent, complete gene knockout and is ideal for studying essential genes and loss-of-function phenotypes. RNAi (siRNA/shRNA) mediates transient gene knockdown, which is useful for studying essential genes that would be lethal if completely knocked out and for mimicking partial inhibition that might be achieved with drugs. Consider the duration of your experiment and the required level of gene silencing when selecting your tool.

Q2: Why is my negative control showing phenotypic effects in my screen? This often indicates off-target effects. For RNAi screens, this can be due to seed-sequence-based miRNA-like effects. For CRISPR screens, it can result from guide RNAs (gRNAs) with off-target activity. Solutions include: using validated, pre-designed libraries with minimal off-target potential; employing multiple independent gRNAs/siRNAs per gene to confirm phenotype; and using controls with scrambled sequences. Continuously updated genome annotations also help in designing more specific reagents [6].

Q3: What are the key considerations for NGS library prep from low-quality or low-quantity samples? For low-input samples (e.g., single-cells or FFPE-derived DNA), use library prep kits specifically designed for low input that incorporate whole-genome amplification or specialized ligation chemistries. For degraded RNA (low RIN), consider using rRNA depletion instead of poly-A selection for RNA-seq, as it is less dependent on RNA integrity. Always use fluorometric methods for accurate quantification of scarce samples.

Q4: How can I ensure my screening library remains relevant with evolving genome annotations? Genome assemblies and annotations are continuously refined. To ensure your reagents (like sgRNAs or RNAi) remain accurate, work with providers who practice reannotation and realignment [6]. Reannotation involves remapping existing reagents against the latest genome references. Realignment is a deeper process that involves redesigning reagents using advanced bioinformatics and recent genomic insights to ensure broader coverage of gene isoforms and variants, reducing the instance of false positives [6].

Q5: Our lab is seeing inconsistent screening results between different operators. How can we improve reproducibility? Intermittent failures often trace back to human error in manual protocols [5]. To improve consistency:

- Introduce detailed, step-by-step SOPs with critical steps highlighted.

- Use master mixes for reactions to reduce pipetting error and variability.

- Implement technician checklists and cross-checking.

- Consider automation for key steps like liquid handling to minimize operator-to-operator variation [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Essential Reagents and Kits for Functional Genomics

| Reagent / Kit Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits [25] | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from various sample types (tissue, blood, cells). | Choose based on sample type and yield requirements. Assess protocols for nuclease-rich tissues and options for low-input samples. |

| NGS Library Prep Kits [22] [5] | Convert purified nucleic acids into sequencer-compatible libraries. | Select based on application (WGS, WES, targeted, RNA-seq), input requirements, and need for automation. Look for kits that minimize bias and adapter dimer formation. |

| CRISPR Reagents [6] [24] | Enable precise gene knockout, base editing, or modulation. | Opt for reagents with high on-target efficiency and low off-target effects. Ensure gRNA designs are aligned to the latest genome build [6]. Consider Cas enzyme variants with different PAM specificities. |

| RNAi Reagents (siRNA/shRNA) [6] | Mediate transient or stable gene knockdown. | Select reagents with validated efficiency and specificity. Libraries should be frequently reannotated to the current transcriptome to ensure target relevance [6]. |

| qPCR Master Mixes [26] | Enable precise quantification of gene expression or validation of targets. | Use Hot-Start enzymes to improve specificity. Choose mixes compatible with your detection chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan probes). |

| Functional Genomics Libraries [21] [23] | Pre-designed collections of CRISPR gRNAs or RNAi molecules for large-scale screens. | Ensure library coverage is comprehensive for your target gene set. Prefer libraries that are empirically validated and designed with multiple guides/RNAs per gene for robust results. |

| Icosabutate | Icosabutate FFAR1/FFAR4 Agonist|MASH Research | Icosabutate is an oral, liver-targeted FFAR1/FFAR4 agonist for MASH research. It demonstrates anti-fibrotic effects in clinical trials. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| iRucaparib-AP6 | iRucaparib-AP6, MF:C46H55FN6O11, MW:887.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a functional genomics screening project, from initial design to data interpretation, highlighting key decision points.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Genome-Scale CRISPR Knockout Screen

- Library Design: Use a pre-validated, genome-scale sgRNA library (e.g., Brunello or GeCKO). Ensure the library is aligned to the most recent genome assembly for your model organism [6].

- Virus Production: Package the sgRNA library into lentiviral particles in a large-scale transfection of HEK293T cells. Titrate the virus to achieve a low MOI (Multiplicity of Infection ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA.

- Cell Transduction: Infect your target cells at a high coverage (e.g., 500x representation per sgRNA) to maintain library diversity. Select transduced cells with puromycin for 3-5 days.

- Phenotypic Selection: Split the cells into experimental and control arms. Apply the selective pressure (e.g., a drug treatment) to the experimental arm for an extended period (e.g., 2-3 weeks), while the control arm is passaged normally.

- Sequencing Library Prep: Harvest genomic DNA from both arms at the end point. Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences using PCR with barcoded primers to create sequencing libraries [5].

- Data Analysis: Sequence the libraries and count the reads for each sgRNA. Use specialized software (e.g., MAGeCK or CERES) to compare sgRNA abundance between control and experimental conditions, identifying genes for which sgRNAs are significantly depleted (essential genes) or enriched (resistance genes).

Protocol 2: Hit Validation Using Orthogonal Methods

- Prioritization: Select top candidate genes from the primary screen for validation.

- Orthogonal Tool Validation: For a hit identified by CRISPR, validate using independent siRNA oligos. Conversely, validate an RNAi hit using CRISPR with independently designed gRNAs targeting the same gene.

- Phenotypic Re-confirmation: In a low-throughput format, transfect/transduce the validation reagents into fresh cells and re-measure the phenotype using a different, quantitative assay than the primary screen (e.g., if the screen used cell proliferation, validate with a caspase assay for apoptosis or a Western blot for a downstream pathway protein).

- Rescue Experiments: To confirm specificity, perform a rescue experiment by expressing an RNAi-resistant or CRISPR-resistant cDNA version of the target gene and demonstrate that this reverses the observed phenotypic effect.

The functional genomics field is propelled by powerful technological advancements and growing integration with AI and multi-omics data. Success in this environment depends not only on accessing the latest tools but also on mastering the foundational techniques. This technical support center, with its detailed troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and workflow visualizations, provides a resource for researchers to optimize their screening libraries, troubleshoot common pitfalls, and generate robust, reproducible data that accelerates the journey from genetic association to biological understanding and therapeutic discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key considerations when designing a gRNA library? Designing an effective gRNA library requires balancing three primary factors: specificity (minimizing off-target effects), efficacy (efficiently guiding the nuclease to create the desired edit), and coverage (comprehensively targeting all genes or genomic regions of interest). [27] Advanced design now often incorporates machine learning algorithms trained on vast experimental datasets to predict and enhance gRNA performance. [27]

2. Can smaller gRNA libraries be as effective as larger ones? Yes, recent research demonstrates that smaller, more optimized libraries can perform as well as, or even better than, larger conventional libraries. The key is using principled criteria for gRNA selection. One study showed that a minimal library with only the top 3 guides per gene, chosen based on high VBC scores, achieved stronger depletion of essential genes than larger 6-guide libraries. [28]

3. What is a dual-targeting library and what are its advantages? A dual-targeting library uses two gRNAs designed to target the same gene. This strategy can create more effective knockouts by inducing a deletion between the two cut sites. It has been shown to produce stronger depletion of essential genes and weaker enrichment of non-essential genes compared to single gRNAs, potentially boosting screening efficiency. [28] However, it may also trigger a heightened DNA damage response due to creating twice the number of DNA breaks. [28]

4. How can I improve the uniformity of my cloned gRNA library? Library uniformity—having all gRNAs represented at roughly equal abundance—is critical for screening quality. Key cloning optimizations to reduce bias include [29]:

- Ordering oligo templates in both forward and reverse complement orientations to counteract synthesis biases.

- Minimizing PCR cycles during insert preparation to avoid over-amplification.

- Using low temperatures (4°C) during insert gel elution to prevent biased dropout of inserts with lower melting temperatures. These steps can produce libraries with a 90/10 skew ratio under 2, significantly more uniform than legacy protocols. [29]

5. What are the main methods for validating CRISPR editing efficiency? Common validation methods include enzymatic mismatch assays and next-generation sequencing. [30]

- Enzymatic assays (e.g., using T7 Endonuclease I or Authenticase) detect heteroduplex DNA formed by edited and unedited sequences, providing an estimate of efficiency.

- Sequencing-based methods, such as amplicon sequencing, allow for accurate genotyping and precise quantification of editing events, including the detection of specific alterations. [30]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor On-Target Editing Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inefficient gRNA sequence | Redesign gRNAs using predictors that incorporate machine learning and empirical data (e.g., VBC scores, Rule Set 3). [27] [28] |

| Low library uniformity | Optimize library cloning by ordering oligos in both orientations, reducing PCR cycles, and eluting at 4°C. [29] |

| Chromatin inaccessibility | Consult epigenomic data for the target cell type; consider CRISPRa/i screens to modulate activity without cutting. [18] |

Problem: High Off-Target Effects

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| gRNA sequences with low specificity | Use advanced computational tools that employ machine learning models (e.g., RNN-GRU, feedforward neural networks) for off-target prediction. [31] |

| High nuclease expression | Deliver CRISPR components as preassembled Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) to limit activity duration. [30] |

| - | Consider using high-fidelity or engineered Cas variants (e.g., eSpOT-ON, hfCas12Max) with improved specificity. [32] |

Problem: Inconsistent Screen Results

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inadequate library coverage | Ensure sufficient cell coverage per gRNA. Improved library uniformity allows for lower coverage (e.g., 50x), but standard screens often require 500-1000x. [29] |

| Variable gRNA representation | Sequence the plasmid library to check uniformity. A skewed distribution requires re-cloning with optimized protocols. [29] |

| High noise in negative controls | Use dual-targeting gRNAs for stronger signal-to-noise for essential genes, but be cautious of potential DNA damage response. [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Editing Efficiency via Enzymatic Mismatch Detection

This protocol uses enzymes to detect indels in a pooled cell population. [30]

- Isolate Genomic DNA: Extract genomic DNA from the CRISPR-edited cell population.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target genomic locus from the isolated DNA.

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and re-anneal the PCR product. This creates heteroduplexes (mismatched double-stranded DNA) if indels are present.

- Digestion: Treat the re-annealed DNA with a mismatch-sensitive enzyme (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I or Authenticase).

- Analysis: Run the digested product on a gel. Cleaved bands indicate the presence of indels. The ratio of cleaved to uncleaved product provides an estimate of editing efficiency.

Protocol 2: A Benchmarking Workflow for gRNA Library Performance

This methodology describes how to systematically compare the efficacy of different gRNA library designs. [28]

- Library Design: Create a benchmark library by combining gRNAs from several established libraries (e.g., Brunello, Yusa v3) targeting a defined set of essential and non-essential genes.

- Cell Screening: Conduct pooled CRISPR lethality screens in multiple relevant cell lines (e.g., HCT116, HT-29).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate log-fold changes for each gRNA to measure depletion (for essential genes) or enrichment.

- Use algorithms like Chronos to model gene fitness effects across time points.

- Compare the performance of different gRNA sets by analyzing the strength of depletion curves for essential genes.

- Validation: Perform a secondary, biologically relevant screen (e.g., a drug-gene interaction screen) to confirm the hits and performance identified in the lethality screen.

Diagrams

gRNA Library Design and Screen Workflow

Optimized Library Cloning for Uniformity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas Nucleases (e.g., eSpOT-ON, hfCas12Max) | Engineered Cas proteins designed to minimize off-target effects while maintaining high on-target activity. [32] |

| GMP-Grade gRNAs | gRNAs manufactured under Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations, ensuring purity, safety, and consistency, which is critical for clinical development. [33] |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit | A kit for preparing high-quality next-generation sequencing libraries to accurately genotype editing events and analyze screen results. [30] |

| Enzymatic Mismatch Detection Kits (e.g., Authenticase) | Reagents for quick and sensitive detection of indel mutations in edited cell pools, providing an estimate of editing efficiency. [30] |

| Validated Genome-Wide Libraries (e.g., Vienna, Yusa v3) | Pre-designed and tested sets of gRNAs targeting every gene in the genome, enabling systematic functional genomics screens. [28] |

| Jarin-1 | Jarin-1|JAR1 Inhibitor|For Research Use |

| Jms-053 | Jms-053, CAS:1954650-11-3, MF:C13H8N2O2S, MW:256.28 g/mol |

Advanced Screening Methodologies and Translational Applications

While CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (CRISPRko) technology has revolutionized loss-of-function genetic screening, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) offer more nuanced approaches for functional genomics research. These technologies enable precise, reversible modulation of gene expression without permanently altering DNA sequences. CRISPRi uses a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressor domains to reduce gene transcription, whereas CRISPRa employs dCas9 fused to activator domains to enhance it [34]. For researchers optimizing functional genomics screening libraries, these tools provide powerful alternatives to traditional knockout screens, particularly for studying essential genes, modeling pharmacological effects, and investigating gain-of-function phenotypes [34] [35]. This technical support center addresses the specific experimental challenges and considerations when implementing CRISPRi and CRISPRa in your screening workflows.

Section 1: Fundamental Concepts & Applications

How do CRISPRi and CRISPRa Systems Work?

The core of both CRISPRi and CRISPRa systems is a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) that binds to DNA based on guide RNA (gRNA) complementarity but cannot cut the DNA backbone [34]. The transcriptional outcome is determined by the protein domain fused to dCas9.

- CRISPRi (Interference): When targeted to a gene's promoter region, the dCas9 protein physically blocks RNA polymerase, leading to transcriptional repression. In mammalian cells, enhanced repression is achieved by fusing dCas9 to a transcriptional repressor domain like the Krüppel associated box (KRAB), which recruits additional proteins to silence gene expression in an inducible, reversible, and non-toxic manner [34].

- CRISPRa (Activation): This system uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators such as VP64 and p65. When guided to a promoter or enhancer region, these fusion proteins recruit the cellular transcription machinery to initiate or enhance gene expression. More robust activation systems, like the SunTag scaffold, use protein scaffolds to recruit multiple activator domains simultaneously, significantly boosting transcription levels [34].

Key Applications in Functional Genomics

CRISPRi and CRISPRa have become indispensable for sophisticated functional genomic screens, enabling researchers to probe gene function with unprecedented precision.

- Gain-of-Function (GOF) Screening with CRISPRa: CRISPRa is particularly valuable for identifying genes that confer desirable traits when overexpressed. For example, it has been used to screen long non-coding RNAs that mediate resistance to chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia and to drive endogenous gene expression in vivo to identify proto-oncogenes in mouse liver models [34]. In plants, CRISPRa has successfully upregulated defense genes, enhancing disease resistance in crops like tomato and bean [35].

- Loss-of-Function (LOF) Screening with CRISPRi: CRISPRi is ideal for studying essential genes, where complete knockout would be lethal to the cell. It provides a partial, reversible knockdown that more closely mimics drug action [34]. It has been successfully deployed in diverse cell types, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and human iPSC-derived neurons, to identify cell-type-specific essential genes [34].

- Modeling Pharmacotherapy: Because drugs often partially reduce rather than completely eliminate a gene's activity, the transient knockdown achieved by CRISPRi can mimic drug action more accurately than a full knockout [34].

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanisms of CRISPRi and CRISPRa systems.

Section 2: Experimental Design & Workflow

Essential Research Reagents

Successful CRISPRi/a screening depends on a core set of well-designed reagents. The table below summarizes these key components and their functions.

| Component | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Fusion Protein | Core effector; binds DNA and recruits transcriptional modulators. | Choose KRAB repressor for CRISPRi; VP64/p65 or SunTag activator for CRISPRa [34]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Library | Targets dCas9 to specific genomic loci. | Design for promoter/enhancer regions; requires high-quality genome annotation [6] [34]. |

| Lentiviral Delivery System | Efficiently delivers genetic components into cells. | Use low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI ~0.3-0.5) to ensure single gRNA integration per cell [36]. |

| Cell Pool | A population of cells transduced with the full gRNA library. | Maintain high library coverage (>200x) to ensure all gRNAs are represented [4]. |

Critical Steps for Library Design and Screening

A robust experimental workflow is crucial for generating meaningful screening data. The following protocol outlines the key steps, from design to analysis.

gRNA Library Design and Selection

- Target Region: Design gRNAs to bind within ~200 base pairs upstream of the Transcription Start Site (TSS) for optimal activity in CRISPRi/a, unlike CRISPRko which targets coding exons [34].

- Bioinformatic Tools: Utilize established algorithms and design tools that incorporate data from genome-wide validation screens to select highly effective gRNAs [34].

- Reannotation: Continuously remap gRNA sequences to the most current genome assemblies (e.g., NCBI RefSeq) to account for updates in genomic annotations and ensure target specificity [6].

Library Delivery and Cell Pool Generation

- Viral Transduction: Deliver the pooled gRNA library using lentiviral vectors at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI of 0.3-0.5) to maximize the probability that each cell receives only one gRNA [36].

- Selection and Expansion: Apply antibiotics to select successfully transduced cells and expand the population while maintaining a high representation of each gRNA (minimum 500 cells per gRNA, with a sequencing depth of at least 200x recommended) [4] [36].

Phenotypic Screening and Sequencing

- Apply Selection Pressure: Split the cell pool into experimental and control groups. Apply a relevant selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment, nutrient stress, or cell sorting based on a marker).

- Genomic DNA Extraction and NGS: Harvest cells after selection, extract genomic DNA, amplify the integrated gRNA sequences with barcoding, and perform next-generation sequencing to quantify gRNA abundance in each sample [36].

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Identify Hits: Use specialized software tools like MAGeCK to compare gRNA read counts between experimental and control groups. This identifies gRNAs that are significantly enriched or depleted, pointing to genes that confer a fitness advantage or disadvantage under the selection pressure [4] [36].

- Hit Validation: Always confirm screening hits using orthogonal assays, such as individual gRNA validation with RT-qPCR to measure changes in target gene expression.

The following workflow provides a visual summary of a typical pooled CRISPRi/a screening experiment.

Section 3: Troubleshooting FAQs

Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My CRISPRi/a screen shows low gene modulation efficiency. What could be wrong?

- gRNA Design: Ensure your gRNAs are targeting the promoter region effectively. Promoter accessibility and accurate TSS annotation are critical. Use bioinformatic tools that are specifically validated for CRISPRi/a gRNA design [34].

- dCas9 Expression: Confirm that the promoter driving your dCas9-effector fusion is active in your specific cell type. Low expression of the core effector will lead to weak modulation [37].

- Delivery Efficiency: Optimize your viral transduction protocol for your cell line. Different cell types may require different delivery strategies, such as spinfection or the use of enhancer solutions [37].

Q2: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance? This is a common occurrence due to the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence, which affect its binding affinity and the local chromatin environment. To ensure reliable results, it is standard practice to design libraries with 3-4 sgRNAs per gene. The final analysis then aggregates the results across all sgRNAs targeting the same gene to confidently identify true hits [4].

Q3: I am observing high cell toxicity after transduction, not related to the phenotype. How can I mitigate this?

- dCas9 Toxicity: High levels of dCas9 can be toxic to some cell types. To mitigate this, titrate the amount of viral vector used for transduction and use lower expression vectors if available. Engineered dCas9 variants with reduced non-specific binding are also being developed [37] [34].

- Delivery Method: Using a Cas9 protein with a nuclear localization signal can enhance targeting efficiency and reduce cytotoxicity associated with plasmid DNA delivery [37].

Troubleshooting Data Analysis

Q4: If no significant gene enrichment/depletion is observed, is it a problem with my statistical analysis? In most cases, the absence of significant hits is not a statistical error but rather a result of insufficient selection pressure during the screen. If the selective condition is too mild, the phenotypic difference between cells with different gRNAs will be too small to detect. To address this, increase the strength or duration of the selection pressure to enhance the enrichment or depletion signal [4].

Q5: How can I determine if my CRISPR screen was successful? The most reliable method is to include positive control gRNAs in your library that target genes with known, strong effects on your phenotype of interest. The significant enrichment or depletion of these controls in your final dataset is a strong indicator that the screening conditions were effective [4].

Q6: How should I prioritize candidate genes from my screening results?

- Primary Prioritization: Use the results from algorithms like the Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) in MAGeCK, which provide a comprehensive gene-level score and ranking. Genes ranked highest by RRA are most likely to be true hits [4].

- Alternative Approach: You can also prioritize genes by applying thresholds for Log-Fold Change (LFC) and p-value. However, this method may yield more false positives than the RRA-based ranking [4].

Q7: What are the most commonly used tools for CRISPR screen data analysis? The MAGeCK (Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout) tool suite is currently the most widely used. It incorporates two main statistical algorithms: RRA for simple treatment-vs-control comparisons, and MLE for more complex, multi-condition experimental designs [4] [36].

Section 4: Advanced Applications & Future Directions

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to significantly advance CRISPR-based technologies. AI and deep learning models are now being used to optimize the activity of gene editors, guide the engineering of novel tools, and predict functional outcomes of gene modulation [24]. For instance, AI can help predict the most effective gRNA sequences and model the complex outcomes of genome editing, such as the likelihood of generating large deletions or complex rearrangements [24]. Furthermore, the combination of AI with spatial omics data is helping to propel CRISPR screening towards greater precision and context-specific understanding [18]. These advancements will continue to enhance the precision and power of CRISPRi and CRISPRa in functional genomics research.

Platform Comparison: siRNA, shRNA, and esiRNA

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and considerations for the three main RNAi screening platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Major RNAi Screening Platforms

| Feature | siRNA | shRNA | esiRNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Small Interfering RNA | Short Hairpin RNA | Endoribonuclease-prepared siRNA |

| Form | Synthetic, double-stranded RNA | DNA vector expressed in cells | Heterogeneous mixture of siRNAs |

| Delivery | Transfection (e.g., lipids) | Viral transduction (e.g., lentivirus) or plasmid transfection [3] | Transfection (e.g., lipids) [38] |

| Knockdown Duration | Transient (typically 3-7 days) [3] | Stable, long-term [3] | Transient [38] |

| Typical Format | Arrayed in well plates [39] | Arrayed or Pooled lentiviral [3] | Individual or library [38] |

| Key Advantage | Ready-to-use; rapid knockdown; defined sequences | Stable integration for long-term studies; suitable for difficult-to-transfect cells [3] | Highly specific; reduced off-target effects due to heterogeneous mixture [38] |

| Primary Consideration | Transfection efficiency required; transient effect | Labor-intensive viral production; potential for insertional mutagenesis | Design requires a minimum 500 bp target region [38] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

General RNAi Screening Questions

Q1: What are the main advantages of using RNAi screening in functional genomics? RNAi screening allows for the systematic knockdown of a wide range of genes to identify those involved in specific biological processes or disease pathways. It is particularly valuable for validating novel drug targets when specific small-molecule inhibitors are not available, providing high specificity through target-specific knockdown [40].

Q2: How reliable and reproducible are RNAi screens? While replicates within a single screen are usually highly self-consistent, the reproducibility of primary hits in secondary screens can be variable [40]. Reliability can be influenced by several biological factors, including the efficiency of protein knockdown, functional redundancy of the target protein, and off-target effects of the RNAi reagent. Therefore, data from multiple screens or with complementary readouts is often necessary for a complete picture [40].

Platform-Specific and Experimental Troubleshooting

Q3: My esiRNA is not available for my gene of interest. What are my options? Many suppliers offer a custom esiRNA synthesis service (often called esiOPEN). This service is independent of the species and requires you to provide a target sequence with a minimum length of 500 base pairs [38].

Q4: How can I validate an observed RNAi phenotype? The best practice is to use an independent reagent that targets a different region of the same mRNA transcript. For esiRNA, this is available as a product called "esiSEC" [38]. For siRNA platforms, this typically involves using a different individual siRNA sequence from the set of three usually provided per gene [39].

Q5: I am getting a weak knockdown phenotype. What should I do?

- Optimize Transfection: Perform a dose-response curve for both the transfection reagent and the RNAi reagent itself. Use a positive control (e.g., Eg5/KIF11 for esiRNA) and a negative control (e.g., Renilla Luciferase) to determine optimal conditions [38].

- Check Protein Turnover: The timing of your assay is critical. For proteins with a slow turnover rate, the maximum knockdown may not be observed until 96 hours post-transfection [38].

- Use a Secondary Reagent: If optimization fails, use a secondary, independently designed reagent (e.g., esiSEC or another siRNA sequence) to rule out issues with the first reagent's design [38].

Q6: How should I handle and store my siRNA library plates?

- Resuspension: Centrifuge plates before opening. Resuspend dried siRNA in nuclease-free water to a stock concentration of ≥1 µM (10 µM is ideal for long-term storage). Pipette up and down gently and incubate at room temperature for at least 10 minutes to ensure complete resuspension [41].

- Aliquoting: Aliquot the resuspended siRNA into working plates to limit freeze-thaw cycles [41].

- Storage: Store resuspended siRNA in a non-frost-free freezer at –20°C or lower. Frost-free freezers should be avoided as their temperature cycles can degrade the RNA [41].

- Freeze-Thaw Limits: Limit freeze-thaw cycles to less than 10 for standard Silencer siRNA and less than 50 for Silencer Select siRNA [41].

Essential Protocols and Workflows

General Workflow for an Arrayed RNAi Screen

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a typical high-throughput, arrayed RNAi screening experiment.

Protocol: Transfection Optimization for siRNA/esiRNA

A critical pre-screening step is to optimize transfection conditions for your specific cell line.

Key Steps:

- Plate Setup: Use a 96-well plate. Include positive control (e.g., Eg5/KIF11, which causes a rounded cell phenotype) and negative control (e.g., Renilla Luciferase siRNA) wells [38].

- Dose-Response: Test a range of concentrations for both the transfection reagent and the RNAi reagent (e.g., 30-200 ng per well for a 96-well plate format) [38] [41].

- Transfection: Use a reverse transfection protocol where the transfection mix is prepared first and cells are added directly to it [41].

- Analysis: After 48-72 hours, analyze the positive control wells for the expected phenotype (e.g., rounded cells for Eg5) and the negative control wells for cytotoxicity. The conditions that yield the strongest phenotype with minimal cytotoxicity are optimal [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNAi Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Silencer Select siRNA Library [39] | A predefined library of highly potent and specific siRNAs; features chemical modifications to reduce off-target effects. Ideal for genome-wide or pathway-focused screens. |

| Mission esiRNA [38] | A heterogeneous mixture of siRNAs targeting a single mRNA; reduces off-target effects. Available as individual genes or custom (esiOPEN). |

| Pooled Lentiviral shRNA Library [3] | A pool of hundreds/thousands of shRNAs delivered via lentivirus; enables genetic screens in hard-to-transfect cells and in vivo studies. |

| Lipid-Based Transfection Reagent | Essential for delivering synthetic RNAi molecules (siRNA, esiRNA) into cells; requires optimization for each cell line [38]. |

| HybEZ Hybridization System [42] | Maintains optimum humidity and temperature during specific assay workflows like RNAscope ISH, which can be used for validating screening hits. |

| Positive Control siRNA (e.g., KIF11/Eg5) [38] | Induces a clear mitotic arrest phenotype (rounded cells); crucial for optimizing transfection efficiency and assessing assay performance. |

| Negative Control siRNA (e.g., RLUC) [38] | A non-targeting siRNA sequence; critical for measuring background noise and ruling out non-specific effects caused by the transfection process itself. |

| JNJ-61432059 | JNJ-61432059, CAS:2035814-50-5, MF:C25H22FN5O2, MW:443.4824 |

| Kahweol oleate | Kahweol Oleate |

High-Content and Automated Screening Integration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between High-Content Imaging (HCI), High-Content Screening (HCS), and High-Content Analysis (HCA)?

While often used interchangeably, these terms describe distinct parts of the workflow [43] [44]:

- High-Content Imaging (HCI): Refers to the automated microscopy technology used to capture high-resolution cellular images.

- High-Content Screening (HCS): Describes the overall high-throughput experiment that applies HCI to screen hundreds to thousands of compounds or genetic perturbations [45].

- High-Content Analysis (HCA): Involves the computational processing of acquired images to extract and analyze quantitative, multiparametric data [46] [43].

Q2: Our automated HCS workflow is producing inconsistent results. What should we check?

Inconsistent results often stem from process control issues. Focus on these areas:

- Instrument Calibration: Ensure automated imagers and liquid handlers are regularly calibrated. Standardized protocols are critical for reproducible image analysis [46].

- Environmental Control: Verify that integrated incubators maintain consistent temperature and COâ‚‚ levels. Automated workcells often use incubated carousels to maintain cell health during extended runs [47] [48].

- Liquid Handling Verification: Check the accuracy of integrated liquid handlers and plate washers. System integration should include real-time data tracking to catalog and protect sample integrity throughout multi-day assays [48].

Q3: How can we improve the analysis of complex biological samples, like 3D organoids, in HCS?

Complex samples like organoids present challenges in scale and data analysis [45].

- Imaging Strategy: For large specimens, use semi-automated methods. Low-magnification prescreening can help identify regions of interest (e.g., specific tissues in zebrafish embryos) for subsequent high-resolution imaging, saving time and resources [49].

- AI-Driven Analysis: Implement machine learning and deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for improved segmentation and feature extraction in heterogeneous samples like 3D models [46].

Q4: What are the key considerations for scaling a lab automation system for HCS?

Start-up systems can be modular and scaled as research needs grow [47].

- Starter Systems: Begin with walk-away automation for core tasks like plate handling and imaging.