sgRNA Design and Efficiency Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Genome Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing and optimizing single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for CRISPR applications.

sgRNA Design and Efficiency Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Genome Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing and optimizing single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for CRISPR applications. It covers foundational principles of CRISPR-Cas9 systems and sgRNA function, explores computational and experimental methodologies for guide design, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers validation strategies for assessing on-target efficiency and minimizing off-target effects. By integrating the latest computational tools, including deep learning models, with practical validation protocols, this resource aims to enhance the success and reliability of genome editing experiments in both research and therapeutic contexts.

The Essential Guide to CRISPR-Cas9 and sgRNA Fundamentals

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system represents a transformative genome editing technology that has revolutionized genetic engineering across diverse fields. Originally discovered as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, CRISPR-Cas9 provides bacteria and archaea with defense mechanisms against viral infections and plasmid transfer [1] [2]. This natural system has been repurposed into a highly precise, efficient, and programmable molecular tool for targeted genome modification in eukaryotic cells, including those of humans, plants, and other organisms [1] [3].

The significance of CRISPR-Cas9 extends far beyond its microbial origins, emerging as the most effective genome editing tool currently available [1]. Its relative simplicity compared to previous gene-editing technologies like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) has democratized genetic engineering, enabling researchers to perform targeted DNA modifications with unprecedented ease and precision [3] [2]. The technology now supports a broad spectrum of applications ranging from therapeutic development and functional genomics to agricultural improvement and disease modeling [1] [4].

Historical Context and Mechanism of Action

Evolution from Bacterial Immunity to Gene Editing Tool

The journey of CRISPR-Cas9 from biological curiosity to powerful biotechnology platform spans several decades. The CRISPR locus was first accidentally identified in 1987 by Ishino and colleagues studying Escherichia coli, who observed unusual repetitive palindromic DNA sequences interrupted by spacers [1]. Francisco Mojica later identified similar sequences in various prokaryotes and coined the term CRISPR in 1990, though its biological function remained unknown at the time [1] [2].

A critical breakthrough came in 2005 when researchers recognized that the spacer sequences in CRISPR arrays often derived from viral DNA, suggesting a role in adaptive immunity [2]. By 2007, experimental evidence confirmed CRISPR as a key component of the prokaryotic immune system, where bacterial cells become immunized against viruses by incorporating short fragments of viral DNA (spacers) into their CRISPR arrays [1]. This genetic memory enables prokaryotes to mount a targeted defense against subsequent viral attacks.

The modern gene-editing application emerged from seminal work by Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, who demonstrated in 2012 that the CRISPR-Cas9 system could be programmed to edit any desired DNA sequence by providing an appropriate RNA template [1] [2]. Their discovery, which earned them the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, established the foundation for harnessing this bacterial defense mechanism as a programmable gene-editing tool.

Molecular Components and Mechanism

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions through two essential components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [1]. The Cas9 protein, most commonly derived from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), is a large multi-domain DNA endonuclease that cleaves target DNA to create double-stranded breaks [1]. Structurally, Cas9 consists of two primary lobes: the recognition lobe (REC), responsible for binding guide RNA, and the nuclease lobe (NUC), containing RuvC and HNH domains that cleave each DNA strand, along with a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) interacting domain that initiates target DNA binding [1].

The guide RNA is a synthetic fusion of two natural RNA components: CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains the 18-20 base pair sequence complementary to the target DNA, and trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a binding scaffold for Cas9 nuclease [1] [3]. This chimeric single-guide RNA (sgRNA) directs Cas9 to specific genomic loci through complementary base pairing [1].

The mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing involves three sequential steps: recognition, cleavage, and repair. The sgRNA directs Cas9 to recognize the target sequence in the gene of interest through complementary base pairing. Cas9 then creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at a site 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence, which for SpCas9 is 5'-NGG-3' (where N can be any nucleotide base) [1]. Finally, the cellular DNA repair machinery resolves these breaks through either Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Multi-domain DNA endonuclease (typically 1368 amino acids from S. pyogenes) | Creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Synthetic fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA | Directs Cas9 to specific genomic loci through complementary base pairing |

| crRNA | 18-20 base pair RNA sequence | Specifies target DNA through complementary binding |

| tracrRNA | Longer structural RNA | Serves as binding scaffold for Cas9 nuclease |

| PAM Sequence | Short conserved sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) | Essential for Cas9 recognition and initiation of DNA binding |

DNA Repair Pathways

The fate of CRISPR-Cas9-induced DNA breaks depends on which cellular repair pathway is engaged. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is an error-prone mechanism that directly ligates broken DNA ends without a template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site [1] [3]. These indels can generate frameshift mutations that disrupt gene function, making NHEJ particularly useful for gene knockout applications [1].

In contrast, Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a precise repair mechanism that uses a homologous DNA template to faithfully restore the damaged sequence [1]. In CRISPR applications, researchers can exploit HDR by providing an exogenous donor template containing desired modifications flanked by homology arms, enabling precise gene insertion or correction [1] [3]. However, HDR occurs at much lower frequency than NHEJ and is primarily active in late cell cycle phases, presenting challenges for high-efficiency precise editing [1].

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism showing key steps from target recognition to DNA repair

Optimization of sgRNA Design and Editing Efficiency

Critical Factors in sgRNA Design

The design of single-guide RNA represents the most crucial determinant of CRISPR-Cas9 editing success, as the sgRNA sequence defines the genomic target for Cas9 cleavage [5]. Efficient sgRNA design requires consideration of multiple parameters, including genomic context, specificity, structural stability, and computational predictions [4] [5].

Recent research has demonstrated that sgRNA efficacy varies significantly depending on target site selection, with some sgRNAs exhibiting high cleavage activity while others prove ineffective despite inducing high INDEL frequencies at the DNA level [4]. This highlights the importance of experimental validation beyond computational prediction alone.

For complex genomes, such as hexaploid wheat with its large genome size (17.1 Gb) and high repetitive DNA content (>80%), specialized sgRNA design strategies are essential [5]. Key considerations include ensuring target uniqueness across subgenomes, minimizing off-target potential against homologous sequences, and optimizing physical parameters like GC content and secondary structure stability [5].

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Efficiency

Recent optimization efforts using inducible Cas9 systems in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) have achieved remarkable editing efficiencies. Through systematic refinement of parameters including cell tolerance to nucleofection stress, transfection methods, sgRNA stability, nucleofection frequency, and cell-to-sgRNA ratios, researchers have established protocols yielding:

Table 2: Achievable Editing Efficiencies with Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 Systems

| Editing Type | Efficiency Range | Key Optimization Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Gene Knockout | 82-93% INDEL efficiency | Optimized nucleofection, chemical sgRNA modifications, cell-to-sgRNA ratio |

| Double-Gene Knockout | >80% INDEL efficiency | Co-delivery of multiple sgRNAs, repeated nucleofection |

| Large Fragment Deletion | Up to 37.5% homozygous deletion | Dual sgRNA targeting, enhanced HDR conditions |

| Point Mutation Knock-in | Variable (HDR-dependent) | ssODN donor design, cell cycle synchronization, NHEJ inhibition |

Notably, comprehensive evaluation of sgRNA scoring algorithms has revealed that Benchling provides the most accurate predictions of cleavage efficiency among commonly used tools [4]. However, researchers identified that certain sgRNAs, such as one targeting exon 2 of ACE2, can exhibit high INDEL rates (80%) while failing to eliminate target protein expression—highlighting a class of "ineffective sgRNAs" that necessitate protein-level validation [4].

Advanced Delivery Methods and Format Considerations

Effective delivery of CRISPR components remains a critical factor in editing efficiency. The format of CRISPR delivery—as DNA, RNA, or pre-complexed ribonucleoprotein (RNP)—significantly impacts editing kinetics, specificity, and cellular toxicity [6].

Table 3: CRISPR Component Delivery Formats and Transfection Methods

| Delivery Format | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Transfection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Cost-effective, stable | Requires transcription/translation, prolonged Cas9 expression increases off-target risk | Lipofection, electroporation |

| mRNA | Faster expression than DNA, no nuclear entry required | Requires translation, immunogenic potential | Electroporation, nucleofection |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Immediate activity, reduced off-target effects, minimal immunogenicity | More expensive, rapid degradation | Nucleofection, microinjection (highest efficiency) |

For sensitive cell types like human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), nucleofection of pre-complexed RNPs has emerged as the gold standard, combining high efficiency with reduced cellular toxicity [4] [6]. Recent advances include chemical modifications to sgRNAs, such as 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both 5' and 3' ends, which significantly enhance sgRNA stability within cells and improve editing outcomes [4].

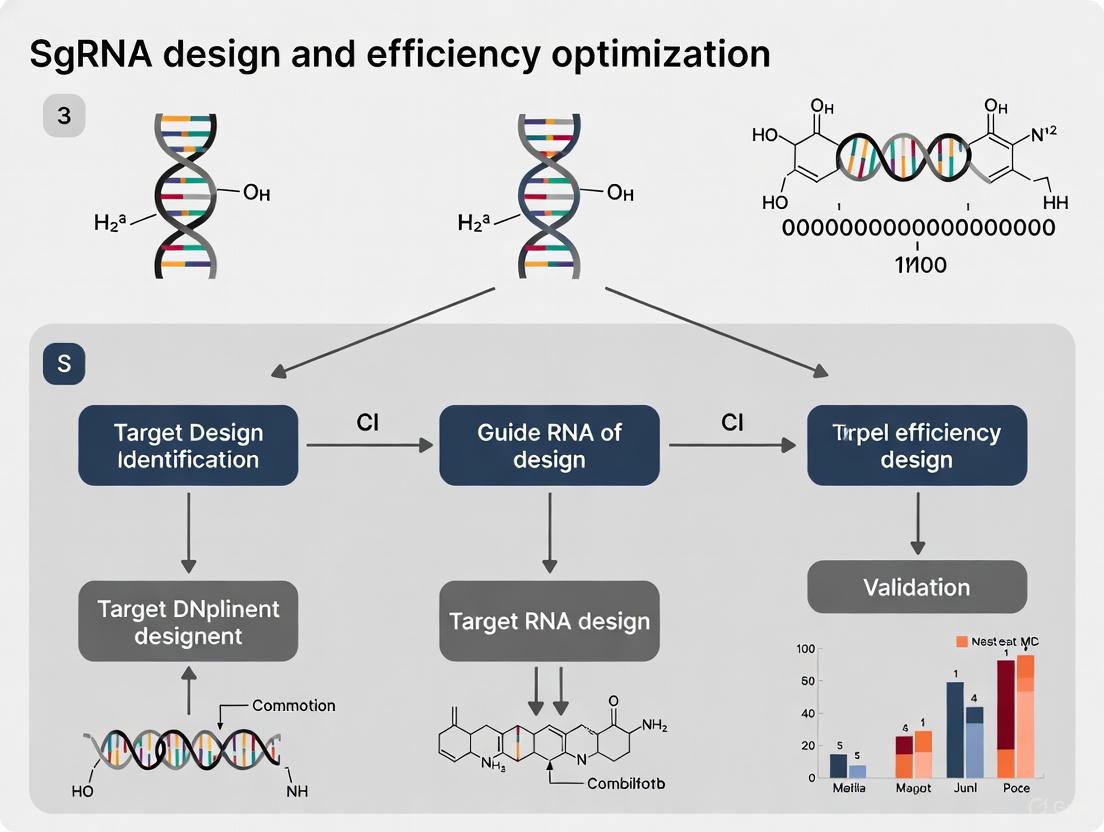

Diagram 2: Workflow for optimizing sgRNA design and CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency

Applications in Research and Therapy

Therapeutic Applications

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has demonstrated remarkable potential across diverse therapeutic areas, with several approaches advancing to clinical trials. In gene therapy, CRISPR-Cas9 offers advantages over traditional methods by enabling precise correction of disease-causing mutations at their native genomic location, potentially avoiding insertional oncogenesis associated with viral vector-mediated gene addition [3].

Promising therapeutic applications include:

Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia: CRISPR-based approaches target the β-globin gene to correct point mutations causing these inherited hemoglobinopathies, with multiple therapies in clinical trials [1] [3].

Oncology: Engineered CAR-T cells with disrupted HLA genes create "universal" allogeneic cell products that evade immune rejection, while tumor-specific mutations are being targeted directly in cancer cells [7].

Monogenic Disorders: Investigations are underway for cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and other single-gene disorders through either gene correction or disruption of disease-causing mutations [1].

Ophthalmic Diseases: Prime editing has successfully corrected pathogenic PRPH2 mutations causing inherited retinal diseases in human induced pluripotent stem cells, restoring normal gene expression without off-target effects [7].

Recent clinical advances include the first successful treatment of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder using allogeneic BCMA-targeted Universal CAR-T therapy developed with CRISPR gene editing, demonstrating the technology's expanding therapeutic reach [7].

Agricultural and Industrial Applications

In agriculture, CRISPR-Cas9 enables the development of improved crop varieties with enhanced nutritional profiles, disease resistance, and environmental resilience [1] [5]. The regulatory distinction for SDN1 and SDN2 genome-edited plants—considered non-transgenic in many countries including the United States, Japan, Australia, and India—has accelerated the adoption of CRISPR technology for crop improvement [5].

In microalgae like Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, optimized CRISPR protocols have facilitated the generation of knockout mutants for studying photosynthesis, metabolism, and developing algal biotechnology applications [8] [9]. Streamlined protocols using commercially available reagents enable rapid mutant generation within five weeks from design to sequencing [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | spCas9, Inducible iCas9 systems, Cas9-modRNA | Provides nuclease activity; inducible systems allow temporal control of editing |

| sgRNA Synthesis | IVT-sgRNA, chemically synthesized modified sgRNA (CSM-sgRNA) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci; chemical modifications enhance stability |

| Delivery Reagents | 4D-Nucleofector systems, lipid nanoparticles, AAV vectors | Introduces CRISPR components into cells; method depends on cell type and application |

| HDR Donor Templates | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), double-stranded DNA donors | Provides repair template for precise edits; ssODNs ideal for point mutations |

| Editing Detection | ICE, TIDE algorithms, T7 endonuclease I assay, next-generation sequencing | Quantifies editing efficiency and characterizes mutation profiles |

| Cell Culture Systems | Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), primary cells, immortalized cell lines | Provide cellular context for editing experiments; hPSCs enable disease modeling |

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its transformative potential, CRISPR-Cas9 technology faces several challenges that require further optimization. Off-target effects remain a primary concern, with studies reporting off-target editing frequencies of ≥50% in some cases [3] [10]. Ongoing efforts to address this limitation include engineered high-fidelity Cas9 variants, optimized guide designs with enhanced specificity, and novel base editor architectures that reduce Cas9-dependent off-target DNA effects [3] [7].

Delivery represents another significant barrier, particularly for in vivo therapeutic applications. While viral vectors like aden-associated virus (AAV) offer high efficiency, they suffer from limited packaging capacity and immunogenicity concerns [3] [2]. Non-viral delivery systems, including lipid nanoparticles and polymer-based vectors, show promise for overcoming these limitations but require further development to achieve clinical-grade efficiency and safety [2].

Ethical considerations surrounding heritable genome editing continue to evolve, with ongoing debates about appropriate applications in human embryos and germline modifications [3]. The scientific community has established temporary moratoriums on certain clinical applications while developing frameworks for responsible research.

Future directions include the development of more precise editing tools like base editors and prime editors, enhanced delivery systems with tissue-specific targeting capabilities, and expanded applications in multiplexed gene regulation and epigenetic modification [7] [2]. As the technology continues to mature, CRISPR-Cas9 is poised to revolutionize both basic research and clinical medicine, offering unprecedented opportunities for understanding and treating genetic diseases.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has emerged as the most versatile and accessible genome editing platform, transforming biological research and therapeutic development. From its origins as a bacterial immune mechanism, CRISPR-Cas9 has been repurposed into a programmable molecular tool that enables precise genetic modifications across diverse organisms. While challenges remain in optimizing sgRNA design, editing efficiency, and delivery specificity, ongoing research continues to address these limitations through novel Cas variants, improved computational tools, and advanced delivery methods. As the technology evolves, CRISPR-Cas9 promises to accelerate both basic research and clinical translation, ultimately enabling new treatments for genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases that have previously proven intractable to conventional therapies.

The single-guide RNA (sgRNA) serves as the indispensable navigational component of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, conferring specificity and precision to this revolutionary genome-editing technology. Structurally, sgRNA is a chimeric non-coding RNA composed of two distinct functional domains: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) component, which contains a user-defined 17-20 nucleotide spacer sequence that confers DNA target specificity through Watson-Crick base pairing, and the trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) scaffold, which facilitates complex formation with the Cas9 nuclease [11]. This synthetic fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA into a single molecule significantly simplified the CRISPR system for experimental and therapeutic applications [12] [11].

The molecular mechanism of sgRNA-guided targeting begins with the formation of a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with Cas9. Once assembled, this complex surveils the genome, with the sgRNA's spacer region probing for complementary DNA sequences [12]. Successful binding and cleavage require two critical conditions: first, the DNA target must demonstrate perfect or near-perfect complementarity to the sgRNA's spacer sequence, particularly in the "seed sequence" region (8-10 bases at the 3' end of the targeting sequence); second, the target must be immediately adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [12] [13]. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" represents any nucleotide [12] [11]. Upon recognizing a valid target sequence, Cas9 undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH), generating a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [12]. This precise molecular targeting mechanism establishes sgRNA as the fundamental determinant of Cas9 precision and efficiency.

Table: Core Components of the sgRNA-Cas9 Complex

| Component | Structure | Function |

|---|---|---|

| crRNA Domain | 17-20 nucleotide variable sequence | Determines DNA target specificity through complementary base pairing |

| tracrRNA Domain | Constant scaffold sequence | Binds Cas9 protein and facilitates RNP complex formation |

| Linker Loop | Connects crRNA and tracrRNA | Structural element in synthetic sgRNA designs [11] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Endonuclease with RuvC and HNH domains | Generates double-strand breaks at targeted DNA sites [12] |

Strategic sgRNA Design for Optimal Performance

Computational Design and Selection Criteria

The design phase represents the most critical determinant of sgRNA performance, influencing both on-target efficiency and off-target effects. Modern sgRNA design incorporates multiple computational parameters to maximize success:

Sequence-Specific Features: Optimal sgRNAs typically demonstrate 40-80% GC content, as higher GC content enhances sgRNA stability while avoiding excessive GC richness that may promote off-target binding [11]. The target sequence should be unique compared to the rest of the genome to ensure specificity, with particular attention to the seed region where mismatches are most disruptive to Cas9 binding [12].

PAM Considerations: The PAM requirement restricts potential target sites but ensures specific genomic targeting. While SpCas9 requires 5'-NGG-3', engineered Cas variants like xCas9 and SpCas9-NG recognize alternative PAM sequences (NG, GAA, GAT), expanding the targetable genomic landscape [12].

Genomic Context: sgRNAs should target regions within 30 base pairs of the desired edit site, particularly for homology-directed repair applications [13]. Accessibility to the target DNA, influenced by chromatin state and epigenetic modifications, significantly affects editing efficiency [14].

Algorithmic Selection and Benchmarking

Several algorithms have been developed to predict sgRNA efficacy, with objective benchmarking essential for protocol optimization. A 2025 study systematically evaluated three widely used scoring algorithms in human pluripotent stem cells with inducible Cas9 expression, finding that Benchling provided the most accurate predictions of sgRNA activity [4]. This empirical validation highlights the importance of algorithm selection in experimental design.

The development of these tools has evolved through analysis of large-scale screening data. Earlier work established Rule Set 1 for sgRNA design based on examination of 1,841 sgRNAs, which was subsequently implemented in genome-wide libraries (Avana and Asiago) [15]. These optimized libraries demonstrated improved performance in both positive and negative selection screens compared to previous designs, identifying 92 hits at FDR < 10% in a vemurafenib resistance screen versus 60 genes with GeCKOv2 [15].

Table: Comparison of sgRNA Design Tools and Features

| Tool Name | Key Features | Cas9 Compatibility | Specialized Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCTop | Off-target prediction, user-defined parameters [4] | SpCas9 and others | Provides off-target sites with mismatch information |

| CHOPCHOP | Visualizes target sites, efficiency scores [13] [11] | Multiple Cas nucleases | Primer design, variant effect prediction |

| CRISPR Design Tool | On/off-target scoring, specificity analysis | Primarily SpCas9 | Oligo design for cloning |

| Synthego Design Tool | 120,000+ genome library, editing efficiency prediction [11] | Multiple platforms | Validates guides from other design methods |

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Efficiency

Methodological Comparison for Efficiency Validation

Rigorous quantification of editing efficiency is essential for evaluating sgRNA performance and validating experimental outcomes. Multiple methods have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay: This mismatch cleavage assay detects heteroduplex DNA formation between wild-type and indel-containing sequences, producing distinguishable bands on agarose gels [14]. While rapid and inexpensive, T7EI provides only semi-quantitative results with limited sensitivity compared to advanced quantitative techniques [14].

Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE): This computational method decomposes Sanger sequencing chromatograms to quantify insertion and deletion frequencies [4] [14]. TIDE provides more quantitative data than T7EI but depends heavily on sequencing quality [14].

Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE): Similar to TIDE, ICE analyzes Sanger sequencing traces through decomposition algorithms but has demonstrated superior accuracy in validation studies [4]. In comparative analyses, ICE predictions showed strong correlation with actual editing outcomes from single-cell clones [4].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): This highly precise method uses differentially labeled fluorescent probes to quantify editing frequencies at single-molecule resolution [14]. ddPCR is particularly valuable for discriminating between different edit types (e.g., NHEJ vs. HDR) and assessing edited versus unedited cell frequencies [14].

A comprehensive 2025 comparative study evaluated these methods using plasmid targets with predefined editing frequencies, providing rigorous benchmarking of their performance characteristics [14]. The selection of an appropriate assessment method should consider required precision, throughput, and available resources.

Experimental Performance Metrics

Recent optimization efforts have dramatically improved achievable editing efficiencies. Through systematic refinement of parameters including cell tolerance to nucleofection stress, transfection methods, sgRNA stability, and cell-to-sgRNA ratios, researchers achieved stable INDEL efficiencies of 82-93% for single-gene knockouts, over 80% for double-gene knockouts, and up to 37.5% homozygous knockout efficiency for large DNA fragment deletions in human pluripotent stem cells [4].

Notably, high INDEL frequency does not always guarantee functional knockout, underscoring the importance of protein-level validation. One study identified an ineffective sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 where edited cells exhibited 80% INDELs but retained ACE2 protein expression, highlighting the critical need for functional validation beyond genotyping [4].

Table: Performance Metrics of Editing Efficiency Assessment Methods

| Method | Sensitivity | Quantitative Capability | Throughput | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7EI Assay | Moderate | Semi-quantitative [14] | High | Limited sensitivity, gel-based quantification |

| TIDE Analysis | Moderate-High | Quantitative [14] | Medium | Dependent on sequencing quality [14] |

| ICE Analysis | High | Quantitative [4] [14] | Medium | Requires validation with reference standard [4] |

| ddPCR | Very High | Highly precise quantification [14] | Medium-High | Requires specific probe design, higher cost |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Variable | Quantitative in live cells [14] | Very High | Artificial context, engineering required [14] |

Experimental Protocols for sgRNA Validation

Workflow for sgRNA Validation in hPSCs

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for sgRNA validation in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), adapted from optimized systems that achieve high-efficiency editing [4]:

Phase 1: sgRNA Preparation

- Design: Select 3-5 sgRNAs per target using computational tools (e.g., Benchling, CCTop) [4]. Prioritize targets with high on-target and low off-target scores.

- Synthesis: Chemically synthesize sgRNAs with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both 5' and 3' ends to enhance stability [4]. Alternatively, employ in vitro transcription for initial screening.

- Quality Control: Quantify sgRNA concentration and verify integrity by electrophoresis.

Phase 2: Delivery and Editing

- Cell Preparation: Culture hPSCs-iCas9 in Pluripotency Growth Medium on Matrigel-coated plates until 80-90% confluency [4].

- Nucleofection: Dissociate cells with EDTA and resuspend in nucleofection buffer. Electroporate using 5μg sgRNA per 8×10^5 cells with program CA137 on Lonza Nucleofector [4].

- Induction: Add doxycycline (dox) to culture medium to induce Cas9 expression (typically 0.5-2μg/mL, concentration requires optimization for specific cell lines).

Phase 3: Efficiency Assessment

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-nucleofection and extract genomic DNA.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target region using high-fidelity polymerase with primers flanking the cut site.

- Editing Quantification: Analyze PCR products by ICE analysis of Sanger sequencing chromatograms [4]. Validate with alternate method (e.g., TIDE or ddPCR) for confirmation.

- Functional Validation: Perform Western blotting to confirm protein knockout, as high INDEL frequency may not always correlate with functional loss [4].

Critical Parameters for Optimization

- Cell-to-sgRNA Ratio: Systematic optimization has demonstrated that 5μg sgRNA for 8×10^5 cells significantly enhances editing efficiency compared to lower ratios [4].

- Nucleofection Frequency: Repeated nucleofection 3 days after initial transfection can boost editing rates for recalcitrant targets [4].

- Control Inclusion: Always include positive control (validated sgRNA) and negative control (non-targeting sgRNA) in each experiment.

- Multi-target Validation: For essential genes, confirm phenotype with multiple independent sgRNAs to rule out off-target effects.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for sgRNA Experimental Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | hPSCs-iCas9 (dox-inducible) [4], lentiCRISPRv2 [15] | Provides tunable nuclease expression with temporal control |

| sgRNA Synthesis | Chemical synthesis with stabilization modifications [4], IVT-sgRNA [4] | Generates functional guide RNAs with enhanced nuclease resistance |

| Delivery Tools | 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza) with P3 Primary Cell Kit [4] | Enables efficient RNP complex delivery to difficult-to-transfect cells |

| Editing Assessment | ICE Analysis [4], TIDE [14], ddPCR [14] | Quantifies on-target efficiency and characterizes editing profiles |

| Cell Culture | PGM1 Medium [4], Matrigel-coated plates [4] | Maintains pluripotency during and after editing procedures |

| Validation Reagents | Western blot antibodies [4], Flow cytometry assays [15] | Confirms functional protein knockout beyond genotyping |

Visualizing sgRNA Structure and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: sgRNA Structure and CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism illustrating the components of sgRNA and its role in directing Cas9 to genomic targets.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for sgRNA Validation depicting the key stages from design to functional validation.

sgRNA stands as the fundamental navigator for Cas9 precision, with its design and optimization critically influencing genome editing outcomes. The integration of sophisticated computational design tools, chemical modifications for enhanced stability, and rigorous validation protocols has enabled remarkable advances in editing efficiency, now achieving >80% INDEL rates in optimized systems [4]. The critical importance of functional validation beyond genotyping, coupled with the availability of diverse assessment methodologies, provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for developing highly effective sgRNAs. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve, refined sgRNA design and delivery approaches will further enhance precision, expanding the therapeutic and research applications of this transformative technology.

The revolutionary precision of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing is orchestrated by two core RNA components that direct the Cas9 nuclease to its DNA target: the crRNA (CRISPR RNA) and the tracrRNA (trans-activating CRISPR RNA). In native bacterial immune systems, these exist as separate molecules [16] [17]. The crRNA contains a customizable 17-20 nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA, serving as the homing device for the system. The tracrRNA, in contrast, features a constant scaffold sequence that is essential for binding to the Cas9 protein, forming the functional backbone of the complex [11] [16].

To simplify the system for laboratory and therapeutic applications, these two independent RNA molecules were engineered into a single chimeric molecule termed the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [11] [13]. This fusion connects the 3' end of the crRNA to the 5' end of the tracrRNA via an artificial linker loop, creating a single RNA transcript that retains the key functions of both original components [11]. This sgRNA chimera has become the predominant format in research due to its experimental convenience, though both systems remain in use and are supported by commercial reagent suppliers [17].

Structural and Functional Analysis of Guide RNA Components

crRNA: The Target-Specific Guide

The crRNA component is the programmable element of the CRISPR system. Its spacer sequence determines the precise genomic locus that will be targeted by the Cas9 nuclease. This sequence must be unique within the genome to ensure specificity and must be immediately adjacent to a short DNA sequence known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which is essential for Cas9 recognition and binding [12]. For the commonly used SpCas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide [11] [12].

tracrRNA: The Cas9 Binding Scaffold

The tracrRNA provides the structural foundation for Cas9 binding and activation. Through extensive base-pairing interactions with the repeat region of the crRNA, the tracrRNA facilitates the maturation of the guide RNA complex and induces a conformational change in the Cas9 protein that shifts it into its active DNA-binding configuration [16] [12]. This activation is crucial for the nuclease activity of Cas9, as the protein remains catalytically inert until properly complexed with the guide RNA [12].

sgRNA: The Engineered Chimera

The chimeric sgRNA combines the crRNA and tracrRNA into a single molecule with six distinct secondary structural modules: spacer, lower stem, bulge, upper stem, nexus, and hairpins (Figure 1) [16]. Mutational analyses have revealed that the bulge and nexus regions are particularly sensitive to disruption and are critically important for DNA cleavage activity [16]. The upper stem, in contrast, exhibits greater tolerance to modification while still maintaining DNA cleavage function. Extensions to the stem-loop structure can enhance sgRNA stability and improve its assembly with SpCas9 [16].

Figure 1: Structural relationship between native two-part guide RNAs and engineered single-guide RNA.

Comparative Analysis of Guide RNA Formats

Performance Comparison of Two-Part vs. Single-Guide RNA Systems

Empirical studies have demonstrated that both two-part guide RNAs (crRNA:tracrRNA duplexes) and chimeric sgRNAs can achieve high editing efficiencies, though performance varies depending on the specific target site. A large-scale study evaluating 255 randomly selected target sites across the genome revealed that the majority (74%) showed genome editing levels exceeding 80%, regardless of the guide RNA format used [17]. However, significant differences were observed at specific target loci, with two-part guide RNAs outperforming sgRNAs at 26.7% of sites, while sgRNAs showed superior activity at 16.9% of sites [17]. The remaining 56.4% of target sites showed no statistically significant difference in editing efficiency between the two formats [17].

Table 1: Comparative analysis of two-part versus single-guide RNA systems

| Parameter | Two-Part Guide RNA | Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Native Structure | Separate crRNA and tracrRNA molecules [16] [17] | Chimeric fusion with linker loop [11] |

| Chemical Synthesis | Shorter oligonucleotides, higher yield, lower cost [17] | Longer oligonucleotide, lower synthesis yield, higher cost [17] |

| Nuclease Susceptibility | More susceptible (4 exposed ends) [17] | Less susceptible (2 exposed ends) [17] |

| Optimal Delivery Method | RNP complexes (direct protein delivery) [17] | Plasmid or mRNA Cas9 delivery (longer stability) [17] |

| Advantages | Potential for enhanced chemical modification [17] | Experimental simplicity, stability with extended expression [17] |

| Editing Efficiency Distribution | Superior at 26.7% of target sites [17] | Superior at 16.9% of target sites [17] |

Strategic Selection Guide for Research Applications

The choice between two-part and single-guide RNA systems should be guided by experimental constraints and objectives. For projects with budget limitations and no other constraints, two-part guide RNAs are generally recommended due to their lower cost [17]. In cellular environments with high nuclease activity, sgRNAs are preferred initially, followed by chemically modified two-part guide RNAs if the first choice proves insufficient [17]. When delivering pre-formed Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, both formats work effectively, though two-part systems are often preferred [17]. Conversely, when using indirect Cas9 delivery methods such as plasmid DNA or mRNA, sgRNAs are recommended due to their superior stability over longer timeframes [17]. If experiencing poor editing efficiency with one format, switching to the alternative format or trying different target sites are both validated troubleshooting strategies [17].

Advanced sgRNA Design Principles and Optimization Protocols

Computational Design and Efficiency Prediction

The design of highly functional sgRNAs has been significantly advanced through large-scale empirical studies and machine learning approaches. Initial sgRNA design rules (Rule Set 1) were developed from the analysis of 1,841 sgRNAs, identifying sequence features correlated with increased efficacy [15]. These rules were implemented in genome-wide libraries (Avana for human, Asiago for mouse) and demonstrated superior performance in both positive and negative selection screens compared to earlier libraries [15]. In positive selection screens, the Avana library identified 92 hits at FDR < 10%, compared to 60 for GeCKOv2 and 27 for GeCKOv1 [15]. For negative selection screens assessing essential genes, the Avana library achieved an AUC of 0.77-0.80, significantly outperforming GeCKO libraries (AUC 0.67-0.70) [15].

Table 2: Key parameters for optimized sgRNA design

| Design Parameter | Optimal Characteristics | Impact on Editing |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 40-80% [11] | Higher GC increases stability; extreme values reduce efficiency |

| Seed Sequence | 8-10 bases at 3' end of spacer [12] | Critical for target recognition; mismatches prevent cleavage |

| Spacer Length | 17-23 nucleotides [11] | Shorter sequences reduce off-target effects but may lose specificity |

| PAM Proximity | Immediate 5' adjacency to spacer [12] | Essential for Cas9 recognition and binding |

| Off-Target Prediction | Minimize sites with ≤3 mismatches [15] | Reduces unintended genomic alterations |

| Target Location | Within 30 bp of desired edit site [13] | Maximizes HDR efficiency for precision editing |

Protocol: High-Efficiency sgRNA Design and Validation

sgRNA Selection and In Silico Analysis

Initiate the design process by selecting an appropriate target gene and region, prioritizing exonic sequences for gene knockouts. Utilize established bioinformatic tools such as CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Design Tool, or Benchling for sgRNA identification [13]. When designing sgRNAs, consider the location of the PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) immediately adjacent to the 3' end of the target sequence [12]. Evaluate potential sgRNAs for optimal GC content (40-80%) and avoid extreme values that may impair function [11]. Perform comprehensive off-target analysis by identifying genomic sites with significant homology, particularly those with minimal mismatches in the seed region [15]. Select 3-5 candidate sgRNAs per target to account for unpredictable activity variations.

Experimental Validation of Editing Efficiency

For transcriptional cloning, clone validated sgRNA sequences into appropriate expression vectors such as lentiCRISPRv2 or lentiGuide that enable co-expression with Cas9 and selection markers [15] [13]. For synthetic approaches, employ chemically modified sgRNAs with stabilization enhancements such as 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both 5' and 3' ends [4]. Deliver CRISPR components using optimized methods—RNP nucleofection for minimal off-target effects or lentiviral transduction for challenging cell types [4] [13]. For human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), implement a doxycycline-inducible Cas9 system (iCas9) to control nuclease expression timing and enhance editing efficiency [4]. Quantify editing efficiency 72-96 hours post-delivery using T7 Endonuclease I assays or targeted deep sequencing to calculate INDEL percentages [4] [13]. For stringent validation of protein knockout, complement DNA-level analysis with Western blotting to confirm loss of target protein expression, as high INDEL frequencies do not always correlate with complete protein ablation [4].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for sgRNA design and validation.

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for guide RNA experimentation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Design Platforms | Benchling, CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Design Tool [13] | In silico design with efficiency prediction |

| Off-Target Prediction | Cas-OFFinder, Off-Spotter [11] | Identification of potential off-target sites |

| Commercial sgRNA Solutions | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 System (IDT) [17] | Chemically modified synthetic guide RNAs |

| Validation Algorithms | ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits), TIDE [4] | Quantification of editing efficiency from sequencing |

| Specialized Cas9 Variants | eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 [12] | Enhanced specificity mutants with reduced off-targets |

| Inducible Systems | Doxycycline-inducible Cas9 (iCas9) [4] | Tunable nuclease expression in sensitive cell models |

| Structure Visualization | FORNA, R2DT [18] [19] | RNA secondary structure analysis and visualization |

Future Directions: AI-Enhanced Editor Design and Structural Innovations

The field of CRISPR guide RNA design is rapidly evolving beyond simple sequence-to-activity prediction. Recent advances demonstrate that large language models (LMs) trained on massive CRISPR-Cas sequence datasets can generate highly functional genome editors with optimal properties that bypass evolutionary constraints [20]. By curating a dataset of more than 1 million CRISPR operons and fine-tuning models on this atlas, researchers have successfully generated Cas9-like effector proteins that are 400 mutations away from natural sequences yet show comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 [20]. This AI-enabled approach has produced 4.8 times the number of protein clusters across CRISPR-Cas families found in nature, dramatically expanding the functional sequence space beyond natural diversity [20].

These AI-designed editors, such as OpenCRISPR-1, represent the next frontier in genome engineering, exhibiting compatibility with base editing and other precision applications [20]. The integration of structural insights with machine learning promises to further refine sgRNA design principles, potentially enabling customized guide architectures optimized for specific genomic contexts or functional outcomes. As these technologies mature, the core components of crRNA, tracrRNA, and their chimeric sgRNA derivative will continue to serve as the fundamental targeting machinery that can be increasingly optimized through computational approaches for enhanced research and therapeutic applications.

In CRISPR-Cas genome editing systems, the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) serves as an essential recognition signal that initiates and licenses DNA cleavage. This short, specific DNA sequence adjacent to the target site is indispensable for distinguishing self from non-self DNA, preventing autoimmunity in bacterial adaptive immunity and enabling precise target selection in genome editing applications. The PAM requirement, however, represents a significant constraint on targeting flexibility, as the Cas nuclease can only bind and cleave DNA at sites flanked by a compatible PAM sequence.

Recent advances have illuminated the complex mechanisms of PAM recognition, revealing it to be a sophisticated process involving not only direct protein-DNA contacts but also long-range allosteric networks and dynamic conformational changes within the Cas protein structure. Engineering Cas variants with altered PAM specificities has emerged as a paramount strategy for expanding the targeting scope of CRISPR technologies, with implications for basic research, therapeutic development, and agricultural biotechnology.

Molecular Mechanisms of PAM Recognition

Structural Basis of PAM Interaction

The molecular recognition of PAM sequences occurs through specific interactions between DNA bases and amino acid residues within the PAM-interacting domain of the Cas protein. For Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the canonical NGG PAM recognition is mediated primarily by an arginine dyad (R1333 and R1335) that forms specific contacts with the guanine bases [21]. Structural analyses reveal that these arginine residues engage in both major groove interactions with nucleobases and backbone contacts, creating a highly specific binding interface.

Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that in wild-type SpCas9, these arginine residues maintain remarkable rigidity, enforcing strict selection for guanine-containing PAM sequences [21]. This rigidity ensures fidelity but limits targeting range. The molecular basis for this specificity stems from arginine's chemical preference for guanine, which offers optimal hydrogen bonding patterns and electrostatic complementarity compared to other nucleobases [21].

Mechanisms of Expanded PAM Recognition

Engineering Cas variants with altered PAM specificities has revealed surprising complexities in PAM recognition mechanisms. Studies on evolved variants like xCas9 demonstrate that expanded PAM compatibility arises not merely from altered direct contacts but from nuanced changes in protein dynamics and allosteric regulation [21].

The xCas9 variant incorporates seven amino acid substitutions throughout the protein, with only one (E1219V) located in the PAM-interacting domain, and even this mutation does not directly contact the PAM DNA [21]. Instead, this substitution introduces flexibility in R1335, enabling this key residue to sample alternative conformations that facilitate recognition of both guanine and adenine-containing PAM sequences [21]. This increased flexibility confers a pronounced entropic preference that improves recognition of both canonical and non-canonical PAMs.

Allosteric Networks in PAM Recognition

Recent research has revealed that efficient PAM recognition requires not only local stabilization but also preservation of long-range allosteric communication with distal protein domains, particularly the REC3 domain that serves as a hub for relaying signals to the HNH nuclease domain [22]. Molecular dynamics simulations and graph-theory analyses demonstrate that mutations which successfully expand PAM compatibility (such as those in VQR, VRER, and EQR variants) maintain these allosteric networks, while unsuccessful engineering attempts disrupt essential communication pathways [22].

Specifically, the D1135V/E substitution—present in multiple successful Cas9 variants—enables stable DNA binding by preserving key interactions (K1107 and S1109) that secure PAM engagement while maintaining allosteric coupling to HNH [22]. This highlights that PAM recognition involves integrated local stabilization, distal coupling, and entropic tuning rather than being a simple consequence of base-specific contacts.

Experimental Characterization of PAM Requirements

GenomePAM: A Novel Method for PAM Characterization

The recent development of GenomePAM represents a significant advancement in PAM characterization methodology, enabling direct determination of PAM preferences in mammalian cells without requiring protein purification or synthetic oligo libraries [23]. This approach leverages naturally occurring repetitive sequences in the mammalian genome as built-in target sites, with each human diploid cell containing approximately 16,942 occurrences of a specific 20-nt protospacer (5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′, termed Rep-1) flanked by nearly random sequences [23].

Table 1: Key Genomic Repeits for PAM Characterization in GenomePAM

| Repeat Name | Sequence (5' to 3') | Occurrences in Human Diploid Genome | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rep-1 | GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC | ~16,942 | Type II nucleases (3' PAM) |

| Rep-1RC | GGCCAGGCACAGTGGCTCAC | ~16,942 | Type V nucleases (5' PAM) |

The GenomePAM workflow involves introducing a guide RNA targeting the repetitive sequence along with a plasmid encoding the candidate Cas nuclease into mammalian cells (typically HEK293T), followed by capture of cleaved genomic sites using GUIDE-seq methodology [23]. Bioinformatic analysis of cleavage sites reveals the PAM sequences that enabled functional recognition and cleavage, providing a comprehensive profile of PAM preferences in a relevant cellular context.

Validation of GenomePAM with Established Nucleases

GenomePAM has been rigorously validated using Cas nucleases with well-characterized PAM requirements, accurately reproducing known specificities [23]:

- SpCas9: Confirmed NGG preference at 3' end of spacer, with 65.6% of edited targets containing G at position 3 and 94.1% of targets containing GG at positions 2-3 [23]

- SaCas9: Identified NNGRRT (R = G/A) PAM requirement, consistent with established literature [23]

- FnCas12a: Verified YYN (Y = T/C) 5' PAM preference using the Rep-1RC target sequence [23]

The method simultaneously assesses activities and fidelities across thousands of match and mismatch sites, providing additional insights into nuclease performance beyond PAM recognition alone [23].

The GenomePAM approach enables quantitative assessment of PAM preferences through calculation of PAM Cleavage Values (PCV), which represent the relative cleavage efficiency across different PAM sequences [23]. This quantitative data can be visualized through sequence logos and heat maps that depict both conservation and tolerance at each PAM position.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined PAM Preferences of Characterized Cas Nucleases

| Cas Nuclease | PAM Sequence | PAM Location | Key Recognizing Residues | Cleavage Efficiency Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (WT) | NGG | 3' | R1333, R1335 | High for NGG, minimal for NGA |

| xCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT | 3' | Flexible R1335 | Broadened with maintained efficiency |

| SaCas9 | NNGRRT | 3' | Not specified in sources | High for NNGRRT |

| FnCas12a | YYN | 5' | Not specified in sources | Dependent on YYN composition |

Computational and AI-Driven Approaches to PAM Analysis

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Advanced computational methods, particularly molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, have provided unprecedented insights into the mechanisms of PAM recognition. Multi-microsecond MD simulations of Cas9 variants bound to different PAM sequences have revealed how flexibility and entropy govern PAM compatibility [21].

These simulations demonstrate that while wild-type SpCas9 maintains rigid arginine residues that enforce strict guanine selection, engineered variants like xCas9 introduce controlled flexibility that enables recognition of alternative PAM sequences while maintaining specificity against non-functional PAMs [21]. For example, xCas9 exhibits specific interaction patterns with recognized PAMs (TGG, GAT, AAG) but shows no significant interactions with ignored PAMs (CCT, TTA, ATC) [21].

AI and Machine Learning for PAM Prediction

Artificial intelligence approaches have revolutionized our ability to predict PAM preferences and design optimized Cas variants. Deep learning models trained on large-scale CRISPR screening data can now accurately forecast the activity of guides across different PAM contexts [24].

Notable AI frameworks include:

- CRISPRon: Integrates sequence features with epigenomic information to predict Cas9 efficiency across different PAM contexts [24]

- Kim et al. model: Specifically predicts activity of SpCas9 variants (xCas9, Cas9-NG) with altered PAM specificities [24]

- Multitask models: Simultaneously optimize for both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity, revealing trade-offs in PAM selection [24]

These AI approaches have revealed that PAM recognition involves complex interdependencies between sequence features, structural constraints, and cellular context, moving beyond simple base-resolution recognition models.

Research Reagent Solutions for PAM Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PAM Characterization Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Plasmids | SpCas9, SaCas9, FnCas12a, xCas9 variants | Provide nuclease source with different inherent PAM requirements |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors | U6-promoter driven backbones | Enable expression of guide RNAs targeting repetitive elements |

| Delivery Tools | Lipofectamine 3000, electroporation systems | Introduce CRISPR components into mammalian cells |

| DSB Capture Reagents | GUIDE-seq dsODN, AMP-seq primers | Tag and amplify double-strand break sites for sequencing |

| Bioinformatic Tools | GenomePAM analysis pipeline, SeqLogo generators | Process sequencing data and visualize PAM preferences |

| Control gRNAs | Validated Rep-1 and Rep-1RC targeting guides | Ensure proper system functionality in PAM characterization |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: PAM Determination Using GenomePAM

Cell Culture and Transfection

- Cell Preparation: Culture HEK293T cells in appropriate medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) until 70-80% confluent.

- Plasmid Transfection: Co-transfect 500 ng Cas9 expression plasmid and 500 ng Rep-1-targeting gRNA plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 according to manufacturer specifications.

- Controls: Include transfection-only controls and non-targeting gRNA controls.

- Incubation: Maintain transfected cells for 48 hours before harvest to allow sufficient editing and dsODN integration.

GUIDE-seq Library Preparation

- dsODN Integration: Introduce GUIDE-seq dsODN during or immediately after plasmid transfection as described [23].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using standard silica-column methods.

- Library Amplification: Perform GUIDE-seq AMP-PCR with primers specific to the dsODN and adapters for next-generation sequencing.

- Quality Control: Verify library quality and size distribution using bioanalyzer or tape station.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Sequence amplified libraries on Illumina platform (minimum 5 million reads per sample).

- Read Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome (hg38) using BWA or Bowtie2.

- Break Site Identification: Identify DSB sites based on read clusters and dsODN integration sites.

- PAM Extraction: Extract 10-bp sequences flanking the Rep-1 target site using custom scripts.

- Logo Generation: Generate sequence logos using WebLogo or similar tools with read counts as weights.

Specificity and Efficiency Assessment

The GenomePAM data enables simultaneous assessment of:

- PAM Specificity: Comprehensive profile of tolerated PAM sequences

- Editing Efficiency: Relative cleavage rates across different PAM contexts

- Off-target Propensity: Analysis of mismatch tolerance across the genome

Understanding PAM recognition mechanisms provides the foundation for expanding CRISPR targeting capabilities and developing next-generation genome editing tools. The integration of innovative experimental methods like GenomePAM with advanced computational approaches and AI-driven design creates a powerful framework for comprehensively characterizing and engineering PAM specificities.

Future directions will likely focus on developing more sophisticated Cas variants with minimal PAM requirements while maintaining high specificity, ultimately working toward truly PAM-less targeting without compromising editing precision. These advances will further expand the therapeutic and research applications of CRISPR technologies, enabling targeting of previously inaccessible genomic loci.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by functioning as highly programmable molecular scissors that create double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations [25] [26]. However, the CRISPR machinery itself does not perform the genetic modification; rather, it initiates a cellular response whereby the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms produce the actual edit while joining the two cut ends [25]. The outcome of a CRISPR editing experiment is therefore determined by which of these competing cellular repair pathways is engaged following the DSB [27].

Two principal pathways dominate DSB repair: Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [25] [26]. These pathways operate concurrently in the cell, and researchers can steer the outcome toward a desired edit by strategically manipulating experimental conditions and designing appropriate repair templates [28]. The decision between NHEJ and HDR is fundamental to experimental design, as NHEJ is ideally suited for gene knockout studies, while HDR enables precise knock-ins [25]. Understanding the mechanistic basis of these pathways and their interplay is crucial for optimizing sgRNA design and overall editing efficiency within the broader context of genome engineering research.

DNA Repair Pathway Mechanisms

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The Rapid Response Mechanism

NHEJ is an error-prone DNA repair pathway that functions throughout the cell cycle by directly rejoining broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [25]. This mechanism often relies on microhomology regions—short sequences of 2-20 nucleotides—flanking the break site, and the repair process frequently results in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) [29] [26]. The stochastic nature of these INDELs makes NHEJ ideal for gene knockout studies, as they can disrupt the coding sequence and lead to frameshift mutations, premature stop codons, and ultimately, loss of gene function [26].

The distinguishing feature of NHEJ is its speed and efficiency, operating as the cell's first responder to DSBs. However, this speed comes at the cost of precision [26]. While traditionally viewed as a method for generating random mutations, with appropriate strategy, NHEJ can also be leveraged for gene knockin generation, albeit with less precision than HDR-based approaches [25].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): The Precision Engineering Pathway

HDR is a precise DNA repair mechanism that utilizes homologous sequences as a template for error-free repair [25]. Unlike NHEJ, HDR is restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, where sister chromatids are available as natural templates [26]. In CRISPR-mediated editing, researchers supply an exogenous donor template containing the desired edit flanked by homology arms—sequences identical to those surrounding the target DSB [25] [30].

This pathway enables sophisticated genetic modifications including:

- Introduction of specific point mutations or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [30]

- Insertion of epitope tags or fluorescent protein sequences [29] [28]

- Precise gene corrections for disease modeling [28]

- Creation of conditional alleles [25]

The principal advantage of HDR is its precision, but this comes with significantly lower efficiency compared to NHEJ, posing a major challenge for researchers [28] [30].

Pathway Competition and Alternative Repair Mechanisms

NHEJ and HDR pathways operate competitively, with NHEJ typically dominating due to its activity throughout the cell cycle and faster kinetics [27]. This competition significantly impacts experimental outcomes, as the majority of DSBs are repaired via the error-prone NHEJ pathway even when an HDR template is provided [28].

Beyond these two primary pathways, additional repair mechanisms contribute to DSB repair outcomes:

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): Utilizes microhomologous sequences (2-20 nt) for repair, often resulting in deletions [29]

- Single-Strand Annealing (SSA): Requires longer homologous sequences and is Rad52-dependent [29]

Recent research indicates that even with NHEJ inhibition, perfect HDR events account for less than 100% of integration events due to the activity of these alternative pathways [29]. The complex interplay between multiple DSB repair pathways necessitates sophisticated experimental design to achieve high rates of precise editing.

The following diagram illustrates the competitive relationship between these key repair pathways following a CRISPR-induced double-strand break:

Quantitative Comparison of NHEJ and HDR

The relative activities of NHEJ and HDR vary significantly depending on experimental conditions. Systematic quantification using digital PCR-based assays reveals that multiple factors influence the HDR/NHEJ ratio, including gene locus, nuclease platform, and cell type [27].

Table 1: Comparative Efficiencies of NHEJ and HDR Under Different Conditions

| Cell Type | Nuclease Platform | Target Locus | HDR Efficiency | NHEJ Efficiency | HDR/NHEJ Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293T | Cas9 | RBM20 | 6.9% | 3.3% | 2.09 |

| HEK293T | Cas9 | GRN | 3.7% | 2.5% | 1.48 |

| HEK293T | Cas9 D10A nickase | RBM20 | 4.2% | 1.6% | 2.63 |

| HeLa | Cas9 | RBM20 | 2.5% | 1.2% | 2.08 |

| Human iPSCs | Cas9 | RBM20 | 1.1% | 0.9% | 1.22 |

Notably, contrary to the common assumption that NHEJ generally occurs more frequently than HDR, studies have found that under multiple conditions, more HDR than NHEJ was induced, with HDR/NHEJ ratios highly dependent on experimental parameters [27].

Table 2: HDR Efficiency Optimization Using Double-Cut Donor Strategy

| Donor Type | Homology Arm Length | Cell Type | HDR Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circular Plasmid | 300 bp | 293T | 0.22% | [30] |

| Circular Plasmid | 600 bp | 293T | 2.5% | [30] |

| Circular Plasmid | 900 bp | 293T | 10.0% | [30] |

| Double-Cut Donor | 300 bp | 293T | 7.5% | [30] |

| Double-Cut Donor | 600 bp | 293T | 20.0% | [30] |

| Double-Cut Donor | 600 bp (+CCND1) | iPSCs | Up to 30% | [30] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Gene Knockout via NHEJ

Objective: To generate gene knockout by exploiting error-prone NHEJ repair to create frameshift mutations.

Materials:

- Cas9 nuclease (protein or plasmid delivery)

- sgRNA complexed with Cas9 (either pre-complexed as RNP or delivered via plasmid)

- Appropriate delivery system (electroporation, lipofection)

- Cell culture reagents

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and sequencing primers for validation

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs targeting early exons of the gene of interest to maximize likelihood of functional knockout. Use algorithms like Benchling for prediction of on-target efficiency [4].

- Complex Formation: Complex Cas9 with sgRNA to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Delivery: Introduce RNP complexes into cells via electroporation. For hPSCs with inducible Cas9, use program CA137 on Lonza Nucleofector [4].

- Recovery: Allow cells to recover for 72-96 hours to enable repair and turnover of native proteins.

- Validation: Extract genomic DNA and amplify target region by PCR. Sequence amplicons and analyze using algorithms like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) to quantify INDEL efficiency [4].

Troubleshooting:

- Low editing efficiency: Optimize cell-to-sgRNA ratio; for hPSCs, use 5μg sgRNA for 8×10ⵠcells [4].

- Cell viability issues: Test cell tolerance to nucleofection stress; consider chemical modifications to enhance sgRNA stability [4].

Protocol for Precise Knock-in via HDR

Objective: To achieve precise insertion of desired sequence using HDR with donor template.

Materials:

- Cas9 nuclease (high-fidelity variants preferred)

- Validated sgRNA with high on-target efficiency

- Donor template (ssODN for small edits, double-cut plasmid for large insertions)

- NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2)

- Cell cycle synchronizers (e.g., Nocodazole, CCND1)

- Flow cytometry reagents if using reporter system

Procedure:

- Donor Design:

- Synchronization: Synchronize cells at G2/M phase using Nocodazole (50-100 ng/mL for 16-18 hours) to favor HDR [30].

- Co-delivery: Co-deliver Cas9-sgRNA RNP complexes with donor template at optimal ratio (e.g., 1:3 for plasmid DNA:donor).

- Pathway Inhibition: Add NHEJ inhibitors immediately after electroporation and maintain for 24 hours [29].

- HDR Enhancement: Consider small molecules that transiently inhibit MMEJ/SSA pathways (e.g., ART558 for POLQ inhibition, D-I03 for Rad52 inhibition) [29].

- Screening: Allow 4-7 days for repair and screen using flow cytometry, antibiotic selection, or single-cell cloning.

Validation:

- For precise edits, use long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio) with computational frameworks like knock-knock for comprehensive genotyping [29].

- Verify absence of random integration and off-target effects.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel experimental paths for creating knockouts versus knock-ins:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Platforms | Wild-type Cas9, Cas12a (Cpf1), Cas9 D10A nickase | Creates DSBs or nicks at target sites; different nucleases have varying PAM requirements and cleavage patterns [29] | Cas9 nickases reduce off-target effects; Cas12a creates staggered ends potentially enhancing HDR [27] |

| Donor Templates | ssODNs (90-200 nt), Double-cut plasmid donors, PCR fragments | Provides homologous template for HDR; double-cut donors show 2-5x higher HDR efficiency [30] | For plasmid donors, 600 bp homology arms optimal; chemical modification of ssODNs enhances stability [4] [30] |

| Pathway Modulators | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi), ART558 (POLQ/MMEJi), D-I03 (Rad52/SSAi) | Inhibits competing repair pathways to enhance HDR efficiency; NHEJ inhibition can increase knock-in efficiency by ~3-fold [29] | Treatment duration critical (typically 24h post-electroporation); combinatorial inhibition shows additive effects [29] |

| Cell Cycle Regulators | Nocodazole, CCND1 (Cyclin D1) | Synchronizes cells in HDR-permissive phases (S/G2); combined use doubles HDR efficiency in iPSCs [30] | Timing crucial; apply before/during editing; concentration optimization required for different cell types [30] |

| Analysis Tools | ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits), TIDE, Knock-knock, Long-read amplicon sequencing | Quantifies editing efficiency and characterizes repair outcomes; long-read sequencing reveals complex integration patterns [29] [4] | ICE provides accurate INDEL quantification; long-read sequencing essential for detecting complex rearrangement [29] [4] |

| Benzyl-PEG2-Azide | Benzyl-PEG2-Azide, MF:C11H15N3O2, MW:221.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Benzyl-PEG5-Amine | Benzyl-PEG5-Amine|PROTAC Linker | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Optimization Strategies

sgRNA Design and Artificial Intelligence

sgRNA design critically influences both editing efficiency and specificity. Advanced algorithms incorporating AI and quantum biology principles are being developed to improve sgRNA design for optimal cutting efficiency [31]. Benchmarking of widely used scoring algorithms indicates that Benchling provides the most accurate predictions for sgRNA efficiency [4]. Notably, sgRNA effectiveness must be empirically validated, as some sgRNAs targeting exon 2 of ACE2 exhibited 80% INDELs but retained protein expression, highlighting the limitation of in silico predictions alone [4].

Combinatorial Pathway Manipulation

While NHEJ inhibition alone significantly improves HDR efficiency, recent evidence shows that imprecise integration still accounts for nearly half of all integration events despite NHEJ inhibition [29]. This suggests involvement of alternative pathways like MMEJ and SSA. Combinatorial inhibition of NHEJ along with MMEJ or SSA pathways reduces nucleotide deletions around the cut site and decreases asymmetric HDR, where only one side of donor DNA is precisely integrated [29]. This multi-pathway suppression approach represents the next frontier in precision editing optimization.

Donor Engineering and Delivery Innovations

The design of the donor template significantly impacts HDR efficiency. Double-cut HDR donors, flanked by sgRNA-PAM sequences and released after CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage, increase HDR efficiency by twofold to fivefold relative to circular plasmid donors [30]. This approach synchronizes genomic DSB formation with donor linearization, enhancing recombination efficiency. For large fragment insertion, 600 bp homology arms provide near-maximal efficiency with 97-100% of donor insertion events mediated by HDR [30].

Strategic sgRNA Design: From Computational Tools to Application-Specific Workflows

The success of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing hinges on the design of the single guide RNA (sgRNA), a molecule that directs the Cas9 nuclease to a specific genomic locus. The core challenge in sgRNA design lies in simultaneously optimizing three interdependent principles: GC content, specificity, and secondary structure. These factors collectively determine the efficiency and accuracy of genomic editing, influencing everything from experimental reproducibility to therapeutic safety. This protocol details comprehensive methodologies for designing and validating sgRNAs that maintain an optimal balance between these principles, providing researchers with a framework for achieving precise and efficient genome editing outcomes.

Quantitative Design Parameters

The thermodynamic and sequence-specific properties of an sgRNA are primary determinants of its performance. The table below summarizes the optimal ranges for key design parameters supported by empirical studies.

Table 1: Key sgRNA Design Parameters and Their Optimal Ranges

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Editing | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Content [32] [33] | 40% - 60% | Editing efficiency increases proportionally with GC content up to ~65%; higher values risk increased off-target effects. [32] | Study in grapevine showed 65% GC content yielded highest editing efficiency. [32] |

| sgRNA Length (spacer sequence) [33] | 17-23 nucleotides | Longer sequences increase off-target risk; shorter sequences compromise specificity. | Standard for SpCas9 system. |

| Self-Folding Free Energy (ΔG) [34] | Higher (less negative) values preferred | Non-functional sgRNAs have significantly lower ΔG (more stable self-folding; ΔG = -3.1) than functional ones (ΔG = -1.9). [34] | Thermodynamic analysis of functional vs. non-functional guides. [34] |

| Duplex Stability (ΔG of gRNA:DNA) [34] | Higher (less negative) values preferred | Non-functional guides form more stable RNA/DNA duplexes (ΔG = -17.2) than functional ones (ΔG = -15.7). [34] | Analysis of RNA/DNA heteroduplex stability. |

| Repetitive Bases [34] | Avoid | Contiguous guanines (GGGG) or other repetitive sequences correlate with poor CRISPR activity and synthesis issues. [34] | Functional gRNAs are significantly depleted of repetitive bases. [34] |

Experimental Protocols for sgRNA Design and Validation

Protocol: In Silico Design and Specificity Analysis

This protocol outlines the bioinformatic workflow for selecting candidate sgRNAs with high predicted on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential.

Materials:

- Software Tools: CRISPOR, Chop-Chop, or Benchling for sgRNA design and off-target prediction. [35]

- Genome Database: Reference genome for your organism (e.g., EnsemblPlants for wheat, GRCh38 for human). [36]

Procedure:

- Input Target Sequence: Obtain the cDNA or genomic DNA sequence of the target gene from a verified database.

- Identify Candidate sgRNAs: Use design software to scan the input sequence for all available protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs, e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) and generate a list of candidate sgRNAs.

- Filter by Specificity:

- For each candidate, review the list of potential off-target sites generated by the software.

- Prioritize sgRNAs with a high on-target score but, crucially, a low number of potential off-target sites and low off-target prediction scores. [35]

- Cross-reference with chromatin accessibility data (e.g., DNase I hypersensitive sites) if available; prefer targets in open chromatin regions for higher efficiency and lower dosage requirements. [35]

- Filter by Sequence Properties:

- Select Final Candidates: Based on the combined analysis, select 3-5 top-ranking sgRNAs for empirical validation.

Protocol: Empirical Validation of sgRNA Efficiency

This protocol describes a standard method for transfecting cells and quantifying the editing efficiency of candidate sgRNAs.

Materials:

- Cell Line: A suitable cell line for your experiment (e.g., human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), NCI-H1703 lung cancer cells). [37] [38]

- CRISPR Components: Plasmid DNA expressing Cas9 and sgRNA, OR in vitro transcribed mRNA for Cas9 and synthetic sgRNA, OR pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. [37] [35]

- Delivery System: Lipofection or electroporation equipment. [37]

- Lysis Buffer: Genomic DNA extraction kit or lysis buffer (e.g., CTAB buffer for plant cells). [32]

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, primers flanking the target site.

- Analysis Method: Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform.

Procedure:

- Deliver CRISPR Components:

- Culture and prepare cells according to standard protocols.

- Co-transfect cells with your chosen form of Cas9 and the candidate sgRNAs. Include a negative control (e.g., cells transfected with a non-targeting sgRNA).

- Recommendation: For the highest specificity and lowest off-target effects, use RNP delivery. [35]

- Harvest Genomic DNA:

- Incubate cells for 5-7 days to allow for editing and protein turnover.

- Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit or method like CTAB. [32]

- Amplify Target Locus:

- Design primers to amplify a 300-500 bp region surrounding the sgRNA target site.

- Perform PCR using a high-fidelity polymerase to minimize amplification errors.

- Quantify Editing Efficiency:

- Sanger Sequencing & Deconvolution: Purify the PCR product and submit for Sanger sequencing. Analyze the resulting chromatogram using a tool like TIDE (Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition) to quantify the percentage of insertions and deletions (indels).

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For a more accurate and quantitative result, prepare an NGS library from the PCR amplicons. Sequence the library and use bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., CRISPResso2) to align sequences and precisely calculate the indel frequency relative to the control.

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for optimizing sgRNA design based on GC content, specificity, and secondary structure:

sgRNA Design Optimization Workflow

Protocol: Implementing Advanced gRNA Designs to Overcome Refractory Sites

Some genomic targets are resistant to editing due to sgRNA misfolding. This protocol utilizes engineered "GOLD" (Genome-editing Optimized Locked Design) gRNAs to address this challenge. [37]

Materials:

- GOLD-gRNA Components: Chemically synthesized crRNA and tracrRNA with a highly stable hairpin (e.g., melting temperature of 71°C) in its constant region, plus proprietary chemical modifications (phosphorothioate bonds and 2'OMe residues, excluding the nexus loop). [37]

- Control: Standard, unmodified sgRNA.

Procedure:

- Design and Synthesize: Design the GOLD-tracrRNA with an elongated, stable hairpin 3' of the nexus. For the crRNA, ensure chemical modifications do not include the nexus loop to preserve protein interactions. [37]

- Test in Cell Culture: Electroporate or lipofect the GOLD-gRNA complex (crRNA duplexed with GOLD-tracrRNA) into Cas9-expressing cells alongside a control standard sgRNA complex. [37]

- Evaluate Efficiency: After 5 days, extract genomic DNA, amplify the target locus by PCR, and sequence the products. Compare the editing efficiency of the GOLD-gRNA to the standard gRNA. Studies have shown this design can increase editing efficiency at refractory sites by up to 1000-fold (from 0.08% to 80.5%). [37]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Optimized sgRNA Design and Validation

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, SpCas9-HiFi) [35] | Reduces off-target effects while maintaining high on-target activity. | Engineered to be more sensitive to base mismatches between sgRNA and DNA. SpCas9-HiFi offers an excellent balance for primary cells. [35] |

| Chemically Modified Synthetic sgRNA [37] [35] | Enhances sgRNA stability and can improve specificity. | Includes phosphorothioate (PS) bonds at ends for nuclease resistance and internal 2'OMe modifications. |