Unlocking Functional Genomics: How NGS is Revolutionizing Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and its transformative role in functional genomics for researchers and drug development professionals.

Unlocking Functional Genomics: How NGS is Revolutionizing Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and its transformative role in functional genomics for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of NGS, details key methodologies like RNA-seq and ChIP-seq, and addresses critical challenges in data analysis and workflow optimization. Furthermore, it covers validation guidelines for clinical applications and offers a comparative analysis of accelerated computing platforms, synthesizing current trends to outline future directions in precision medicine and AI-driven discovery.

From Code to Function: How NGS Deciphers Genomic Secrets

Functional genomics represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving beyond static DNA sequences to dynamic genome-wide functional analysis. This whitepaper defines core concepts in functional genomics and establishes its critical dependence on next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. We examine how this field bridges the gap between genotype and phenotype by studying gene functions, interactions, and regulatory mechanisms at unprecedented scale. For researchers and drug development professionals, we provide detailed experimental methodologies, technical workflows, and analytical frameworks that are transforming target identification, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development. The integration of functional genomics with NGS has created a powerful paradigm for deciphering complex biological systems and advancing precision medicine.

The completion of the Human Genome Project marked a pivotal achievement, providing the first map of our genetic code. However, a map is not a manual—and our journey to truly unlock the genome's power required a new scientific discipline [1]. Functional genomics has emerged as this critical field, bridging the gap between our genetic code (genotype) and our observable traits and health (phenotype) [2] [1].

Defining Functional Genomics

Functional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to describe gene (and protein) functions and interactions on a genome-wide scale [3]. It focuses on the dynamic aspects such as gene transcription, translation, regulation of gene expression, and protein-protein interactions, as opposed to the static aspects of genomic information such as DNA sequence or structures [3]. This approach represents a "new phase of genome analysis" that followed the initial "structural genomics" phase of physical mapping and sequencing [4].

A key characteristic distinguishing functional genomics from traditional genetics is its genome-wide approach. While genetics often examines single genes in isolation, functional genomics employs high-throughput methods to investigate how all components of a biological system—genes, transcripts, proteins, metabolites—work together to produce a given phenotype [3] [4]. This systems-level perspective enables researchers to capture the complexity of how genomes operate in the dynamic environment of our cells and tissues [2].

The Critical Role of the "Dark Genome"

A fundamental insight driving functional genomics is that only approximately 2% of our genome consists of protein-coding genes, while the remaining 98%—once dismissed as "junk" DNA but now known as the "dark genome" or non-coding genome—contains crucial regulatory elements [1]. This dark genome acts as a complex set of switches and dials, directing our 20,000-25,000 genes to work together in specific ways, allowing different cell types to develop and respond to changes [1].

Significantly, approximately 90% of disease-associated genetic changes occur not in protein-coding regions but within this dark genome, where they can impact when, where, and how much of a protein is produced [1]. This understanding has made functional genomics essential for interpreting how most genetic variants influence disease risk and progression.

The Functional Genomics Toolkit: Core Technologies and Methodologies

Next-Generation Sequencing: The Foundation of Modern Functional Genomics

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized functional genomics by providing massively parallel sequencing technology that offers ultra-high throughput, scalability, and speed [5]. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, NGS enables simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, providing comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [6].

Key NGS Platforms and Characteristics:

Table: Comparison of Major NGS Technologies

| Technology | Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Key Applications in Functional Genomics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina [6] | Sequencing by synthesis (reversible terminators) | 36-300 bp (short-read) | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptomics, epigenomics | Potential signal crowding with sample overload |

| PacBio SMRT [6] | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp (long-read) | De novo genome assembly, full-length transcript sequencing | Higher cost per gigabase compared to short-read |

| Oxford Nanopore [7] [6] | Detection of electrical impedance changes as DNA passes through nanopores | 10,000-30,000 bp (long-read) | Real-time sequencing, direct RNA sequencing, portable sequencing | Error rate can reach 15% without correction |

| Gatifloxacin-d4 | Gatifloxacin-d4 Stable Isotope | Gatifloxacin-d4 is a deuterated internal standard for precise pharmacokinetic and antimicrobial resistance research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Progesterone-d9 | Progesterone-d9, CAS:15775-74-3, MF:C21H30O2, MW:323.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Key Methodological Approaches by Molecular Level

Functional genomics employs diverse methodologies targeting different levels of cellular information flow:

At the DNA Level:

- Genetic Interaction Mapping: Systematic pairwise deletion or inhibition of genes to identify functional relationships through epistasis analysis [3].

- DNA/Protein Interactions: Techniques like ChIP-sequencing identify protein-DNA binding sites genome-wide [3].

- DNA Accessibility Mapping: Assays including ATAC-seq and DNase-Seq identify accessible chromatin regions representing candidate regulatory elements [3].

At the RNA Level:

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq): Has largely replaced microarrays as the most efficient method for studying transcription and gene expression, enabling discovery of novel RNA variants, splice sites, and quantitative mRNA analysis [3] [5].

- Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs): Library-based approaches to test the cis-regulatory activity of thousands of DNA sequences in parallel [3].

- Perturb-seq: Combines CRISPR-mediated gene knockdown with single-cell RNA sequencing to quantify effects on global gene expression patterns [3].

At the Protein Level:

- Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Systems: High-throughput method to identify physical protein-protein interactions by testing "bait" proteins against libraries of potential "prey" interacting partners [3].

- Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP/MS): Identifies protein complexes and interaction networks by purifying complexes using tagged "bait" proteins followed by mass spectrometry [3].

- Deep Mutational Scanning: Multiplexed approach that assays the functional consequences of thousands of protein variants simultaneously using barcoded libraries [3].

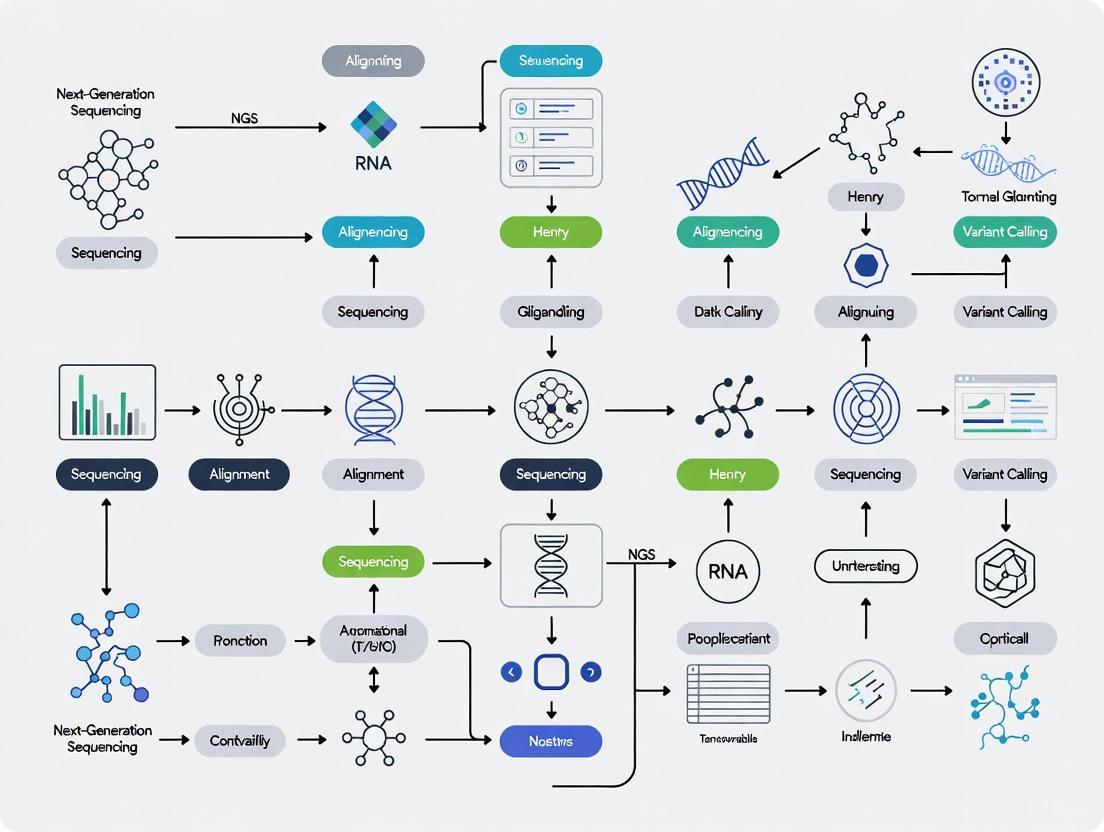

Experimental Workflows in Functional Genomics

Bulk RNA Sequencing Workflow:

Functional Genomic Screening with CRISPR:

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The functional genomics workflow depends on specialized reagents and tools that enable high-throughput analysis. The kits and reagents segment dominates the functional genomics market, accounting for an estimated 68.1% share in 2025 [8]. These components are indispensable for simplifying complex experimental workflows and providing reliable data.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Functional Genomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | DNA/RNA purification kits, magnetic bead-based systems | Isolation of high-quality genetic material from diverse sample types | Critical for reducing protocol variability; influences downstream analysis accuracy [8] |

| Library Preparation Kits | NGS library prep kits, transposase-based tagmentation kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries with appropriate adapters and barcodes | Enable multiplexing; reduce hands-on time through workflow standardization [5] |

| CRISPR Reagents | sgRNA libraries, Cas9 expression systems, screening libraries | Targeted gene perturbation for functional characterization | Library complexity and coverage essential for comprehensive screening [3] [9] |

| Enzymatic Mixes | Reverse transcriptases, polymerases, ligases | cDNA synthesis, amplification, and fragment joining | High fidelity and processivity required for accurate representation [8] |

| Probes and Primers | Targeted sequencing panels, qPCR assays, hybridization probes | Specific target enrichment and quantification | Design critical for specificity and coverage uniformity [4] |

Applications in Drug Development and Precision Medicine

Transforming Target Discovery and Validation

Functional genomics has become indispensable for pharmaceutical R&D, enabling de-risking of drug discovery pipelines. Drugs developed with genetic evidence are twice as likely to achieve market approval—a vital improvement in a sector where nearly 90% of drug candidates fail, with average development costs exceeding $1 billion and timelines spanning 10–15 years [1].

Companies across the sector are leveraging functional genomics to refine disease models and optimize precision medicine strategies. For instance, CardiaTec Biosciences applies functional genomics to dissect the genetic architecture of heart disease, identifying novel targets and understanding disease mechanisms at a cellular level [1]. Similarly, Nucleome Therapeutics focuses on mapping genetic variants in the "dark genome" to their functional impact on gene regulation, discovering novel drug targets for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [1].

Clinical Applications in Oncology

Functional genomics has demonstrated particular success in cancer research and treatment. The discovery that the HER2 gene is overexpressed in certain breast cancers—enabling development of the targeted therapy Herceptin—represents an early success story of functional genomics guiding drug development [9]. This paradigm of linking specific genetic alterations to targeted treatments now forms the foundation of precision oncology.

RNA sequencing has been shown to successfully detect relapsing cancer up to 200 days before relapse appears on CT scans, leading to its increasing adoption in cancer diagnostics [9]. The UK's National Health Service Genomic Medicine Service has begun implementing functional genomic pathways for cancer diagnosis, representing a significant advancement in clinical genomics [9].

Functional Genomics in Biomedical Research

The integration of functional genomics with advanced model systems is accelerating disease mechanism discovery. The Milner Therapeutics Institute's Functional Genomics Screening Laboratory utilizes state-of-the-art liquid handling robotics and automated systems to enable high-throughput, low-noise arrayed CRISPR screens across the UK [1]. This capability allows researchers to investigate fundamental disease mechanisms in more physiologically relevant contexts, particularly using human in vitro models like organoids.

Single-cell genomics and spatial transcriptomics represent cutting-edge applications that reveal cellular heterogeneity within tissues and map gene expression in the context of tissue architecture [7]. These technologies provide unprecedented resolution for studying tumor microenvironments, identifying resistant subclones within cancers, and understanding cellular differentiation during development [7].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Analytical Hurdles

Despite rapid progress, functional genomics faces several significant challenges:

Data Volume and Complexity: NGS technologies generate terabytes of data per project, creating substantial storage and computational demands [7]. Cloud computing platforms like Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud Genomics have emerged as essential solutions, providing scalable infrastructure for data analysis [7].

Ethnic Diversity Gaps: Genomic studies suffer from severe population representation imbalances, with approximately 78% of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) based on European ancestry, while African, Asian, and other ethnicities remain dramatically underrepresented [9]. This disparity threatens to create precision medicine benefits that are not equally accessible across populations.

Functional Annotation Limitations: Interpretation of genetic variants remains challenging due to incomplete understanding of biological function [9]. While comprehensive functionally annotated genomes are being assembled, the dynamic nature of the transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, and metabolome creates substantial analytical complexity.

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

The functional genomics landscape continues to evolve rapidly, driven by several technological trends:

AI and Machine Learning Integration: Tools like Google's DeepVariant utilize deep learning to identify genetic variants with greater accuracy than traditional methods [7]. AI models are increasingly used to analyze polygenic risk scores for disease prediction and to identify novel drug targets by integrating multi-omics data [7].

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics provides a more comprehensive view of biological systems [7] [4]. This integrative approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex diseases like cancer, where genetics alone does not provide a complete picture [7].

Long-Read Sequencing Advancements: Platforms from Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore Technologies are overcoming traditional short-read limitations, enabling more complete genome assembly and direct detection of epigenetic modifications [6].

The global functional genomics market reflects this growth trajectory, estimated at USD 11.34 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 28.55 billion by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate of 14.1% [8]. This expansion underscores the field's transformative potential across basic research, therapeutic development, and clinical application.

Functional genomics represents the essential evolution from cataloging genetic elements to understanding their dynamic functions within biological systems. By leveraging NGS technologies and high-throughput experimental approaches, this field has transformed our ability to connect genetic variation to phenotype, revealing the complex regulatory networks that underlie health and disease. For researchers and drug development professionals, functional genomics provides powerful tools for target identification, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development—ultimately enabling more precise and effective medicines. As technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, functional genomics will increasingly form the foundation of biological discovery and precision medicine.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in molecular biology, transforming genetic analysis from a targeted, small-scale endeavor to a comprehensive, genome-wide scientific tool. This revolution has unfolded through distinct technological generations, each overcoming limitations of its predecessor while introducing new capabilities for functional genomics research. The journey from short-read to long-read technologies has not merely been an incremental improvement but a complete reimagining of how we decode and interpret genetic information, enabling researchers to explore biological systems at unprecedented resolution and scale. Within functional genomics, this evolution has been particularly transformative, allowing scientists to move from static sequence analysis to dynamic investigations of gene regulation, expression, and function across diverse biological contexts and timepoints [10].

The impact of this sequencing revolution extends across the entire biomedical research spectrum. In drug development, NGS technologies now inform target identification, biomarker discovery, pharmacogenomics, and companion diagnostic development [11]. The ability to generate massive amounts of genetic data quickly and cost-effectively has accelerated our understanding of disease mechanisms and enabled more personalized therapeutic approaches. This technical guide explores the historical development, methodological principles, and practical applications of NGS technologies, with particular emphasis on their transformative role in functional genomics research and drug development.

Historical Evolution of Sequencing Technologies

From Sanger to Massively Parallel Sequencing

The history of DNA sequencing began with first-generation methods, notably Sanger sequencing, developed in 1977. This chain-termination method was groundbreaking, allowing scientists to read genetic code for the first time, and became the workhorse for the landmark Human Genome Project. While highly accurate (99.99%), this technology was constrained by its ability to process only one DNA fragment at a time, making whole-genome sequencing a monumental effort requiring 13 years and nearly $3 billion [12] [13].

The early 2000s witnessed the emergence of second-generation sequencing, characterized by massively parallel analysis. This "next-generation" approach could simultaneously sequence millions of DNA fragments, dramatically improving speed and reducing costs. The first major NGS technology was pyrosequencing, which detected pyrophosphate release during DNA synthesis. However, this was soon surpassed by Illumina's Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) technology, which used reversible terminator-bound nucleotides and quickly became the dominant platform following the launch of its first sequencing machine in 2007 [13]. This revolutionary approach transformed genetics into a high-speed, industrial operation, reducing the cost of sequencing a human genome from billions to under $1,000 and the time required from years to mere hours [12].

The Rise of Third-Generation Sequencing

Despite their transformative impact, short-read technologies faced inherent limitations in resolving repetitive regions, detecting large structural variants, and phasing haplotypes. This led to the development of third-generation sequencing, represented by two main technologies: Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing from Pacific Biosciences (introduced in 2011) and nanopore sequencing from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (launched in 2015) [13].

These long-read technologies sequence single DNA molecules without amplification, eliminating PCR bias and enabling the detection of epigenetic modifications. PacBio's SMRT sequencing uses fluorescent signals from nucleotide incorporation by DNA polymerase immobilized in tiny wells, while nanopore sequencing detects changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [13] [14]. Oxford Nanopore's platform notably demonstrated the capability to produce extremely long reads—up to 1 million base pairs—though with initially higher error rates that have improved significantly through technological refinements [15].

Table 1: Evolution of DNA Sequencing Technologies

| Generation | Technology Examples | Key Features | Read Length | Accuracy | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Sanger Sequencing | Processes one DNA fragment at a time; chain-termination method | 500-1000 bp | ~99.99% | Targeted sequencing; validation of variants |

| Second Generation | Illumina SBS, Ion Torrent | Massively parallel sequencing; requires DNA amplification | 50-600 bp | >99% per base | Whole-genome sequencing; transcriptomics; targeted panels |

| Third Generation | PacBio SMRT, Oxford Nanopore | Single-molecule sequencing; no amplification needed | 1,000-20,000+ bp (PacBio); up to 1M+ bp (Nanopore) | ~99.9% (PacBio HiFi); variable (Nanopore) | De novo assembly; complex variant detection; haplotype phasing |

Technical Foundations: From Short-Read to Long-Read Sequencing

Short-Read Sequencing Technologies and Methodologies

Short-read sequencing technologies, dominated by Illumina's Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), operate on the principle of massively parallel sequencing of DNA fragments typically between 50-600 bases in length [16]. The fundamental workflow consists of four main stages:

Library Preparation: DNA is fragmented into manageable pieces, and specialized adapter sequences are ligated to the ends. These adapters enable binding to the sequencing platform and serve as priming sites for amplification and sequencing. For targeted approaches, fragments of interest may be enriched using PCR amplification or hybrid capture with specific probes [16].

Cluster Generation: The DNA library is loaded onto a flow cell, where fragments bind to its surface and are amplified in situ through bridge amplification. This process creates millions of clusters, each containing thousands of identical copies of the original DNA fragment, providing sufficient signal intensity for detection [12].

Sequencing by Synthesis: The flow cell is flooded with fluorescently-labeled nucleotides that incorporate into the growing DNA strands. After each incorporation, the flow cell is imaged, the fluorescent signal is recorded, and the termination reversible is cleaved to allow the next incorporation cycle. The specific fluorescence pattern at each cluster determines the sequence of bases [12] [16].

Data Analysis: The raw image data is converted into sequence reads through base-calling algorithms. These short reads are then aligned to a reference genome, and genetic variants are identified through specialized bioinformatics pipelines [16] [10].

Short-read sequencing workflows follow a structured process from sample preparation to data analysis, with each stage building upon the previous one to generate final variant calls.

Alternative short-read technologies include Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing, which detects pH changes during nucleotide incorporation rather than fluorescence, and Element Biosciences' AVITI System, which uses sequencing by binding (SBB) to create a more natural DNA synthesis process [15]. While these platforms differ in detection methods, they share the fundamental characteristic of generating short DNA reads that provide high accuracy but limited contextual information across complex genomic regions.

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies and Methodologies

Long-read sequencing technologies address the fundamental limitation of short-read approaches by sequencing much longer DNA fragments—typically thousands to tens of thousands of bases—from single molecules without amplification [14]. The two primary technologies have distinct operational principles:

PacBio Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing: This technology uses a nanofluidic chip called a SMRT Cell containing millions of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs)—tiny wells that confine light observation volume. Within each ZMW, a single DNA polymerase enzyme is immobilized and synthesizes a complementary strand to the template DNA. As nucleotides incorporate, they fluoresce, with each nucleotide type emitting a distinct color. The key innovation is HiFi sequencing, which uses circularized DNA templates to enable the polymerase to read the same molecule multiple times (circular consensus sequencing), generating highly accurate long reads (15,000-20,000 bases) with 99.9% accuracy [14].

Oxford Nanopore Sequencing: This technology measures changes in electrical current as single-stranded DNA passes through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane. Each nucleotide disrupts the current in a characteristic way, allowing real-time base identification. A significant advantage is the ability to produce extremely long reads (theoretically up to 1 million bases), direct RNA sequencing, and detection of epigenetic modifications without additional processing [15].

Illumina Complete Long Reads: While technically a short-read technology, Illumina's approach leverages novel library preparation and informatics to generate long-range information. Long DNA templates are introduced directly to the flow cell, and proximity information from clusters in neighboring nanowells is used to reconstruct long-range genomic insights while maintaining the high accuracy of short-read SBS chemistry [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

| Parameter | Short-Read Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-600 bases | 1,000-20,000+ bases (PacBio); up to 1M+ bases (Nanopore) |

| Accuracy | >99% per base (Illumina) | ~99.9% (PacBio HiFi); variable (Nanopore, improved with consensus) |

| DNA Input | Amplified DNA copies | Often uses native DNA without amplification |

| Primary Advantages | High accuracy; low cost per base; established protocols | Resolves repetitive regions; detects structural variants; enables haplotype phasing |

| Primary Limitations | Struggles with repetitive regions; limited phasing information | Historically higher cost; higher DNA input requirements; computationally intensive |

| Ideal Applications | Variant discovery; transcriptome profiling; targeted sequencing | De novo assembly; complex variant detection; haplotype phasing; epigenetic modification detection |

Long-read sequencing workflows maintain the native state of DNA throughout the process, enabling detection of base modifications and structural variants that are challenging for short-read technologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of NGS technologies in functional genomics research requires careful selection of platforms and reagents tailored to specific research questions. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Applications in Functional Genomics

| Product/Technology | Provider | Primary Function | Applications in Functional Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina SBS Chemistry | Illumina | Sequencing by Synthesis with reversible terminators | Whole-genome sequencing; transcriptomics; epigenomics |

| PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Pacific Biosciences | Long-read, high-fidelity sequencing via circular consensus | De novo assembly; haplotype phasing; structural variant detection |

| Oxford Nanopore Kits | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Library preparation for nanopore sequencing | Real-time sequencing; direct RNA sequencing; metagenomics |

| TruSight Oncology 500 | Illumina | Comprehensive genomic profiling from tissue and blood | Cancer biomarker discovery; therapy selection; clinical research |

| AVITI System | Element Biosciences | Sequencing by binding with improved accuracy | Variant detection; gene expression profiling; multimodal studies |

| DNBSEQ Platforms | MGI | DNA nanoball-based sequencing | Large-scale population studies; agricultural genomics |

| Ion Torrent Semiconductor | Thermo Fisher | pH-based detection of nucleotide incorporation | Infectious disease monitoring; cancer research; genetic screening |

| Iomeprol | `Iomeprol | Iomeprol is a non-ionic, low-osmolar contrast medium for diagnostic imaging research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| (S)-Acenocoumarol | (S)-Acenocoumarol|Potent VKOR Inhibitor for Research | (S)-Acenocoumarol is a high-potency enantiomer used in anticoagulation research and melanogenesis studies. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Functional Genomics and Drug Development

Functional Genomics Applications

The evolution of NGS technologies has dramatically expanded the toolbox for functional genomics research, enabling comprehensive investigation of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic features:

Whole Genome Sequencing: Both short-read and long-read technologies enable comprehensive variant discovery across the entire genome. Short-read WGS excels at detecting single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels), while long-read WGS provides superior resolution of structural variants, repetitive elements, and complex regions [10] [17].

Transcriptome Sequencing: RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides quantitative and qualitative analysis of transcriptomes. Short-read RNA-seq is ideal for quantifying gene expression levels and detecting alternative splicing events, while long-read RNA-seq enables full-length transcript sequencing without assembly, revealing isoform diversity and complex splicing patterns [10].

Epigenomic Profiling: NGS methods like ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation sequencing) and bisulfite sequencing map protein-DNA interactions and DNA methylation patterns, respectively. Long-read technologies additionally enable direct detection of epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation without chemical treatment [14] [17].

Single-Cell Genomics: Combining NGS with single-cell isolation techniques allows characterization of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic heterogeneity at cellular resolution, revealing complex biological processes in development, cancer, and neurobiology [12].

Drug Development Applications

In pharmaceutical research and development, NGS technologies have become indispensable across the entire pipeline:

Target Identification and Validation: Whole-genome and exome sequencing of patient cohorts identifies genetic variants associated with disease susceptibility and progression, highlighting potential therapeutic targets. Integration with functional genomics data further validates targets and suggests mechanism of action [11] [18].

Biomarker Discovery: Comprehensive genomic profiling identifies predictive biomarkers for patient stratification, enabling precision medicine approaches. For example, tumor sequencing identifies mutations guiding targeted therapy selection, while germline sequencing informs pharmacogenetics [11].

Pharmacogenomics: NGS enables comprehensive profiling of pharmacogenes, identifying both common and rare variants that influence drug metabolism, transport, and response. This facilitates personalized dosing and drug selection to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity [18].

Companion Diagnostic Development: Targeted NGS panels are increasingly used as companion diagnostics to identify patients most likely to respond to specific therapies, particularly in oncology where tumor molecular profiling guides treatment decisions [11].

Experimental Design and Protocol Considerations

Designing NGS Experiments for Functional Genomics

Effective experimental design is critical for generating robust, interpretable NGS data. Key considerations include:

Selection of Appropriate Technology: Choose between short-read and long-read technologies based on research goals. Short-read platforms are ideal for variant detection, expression quantification, and targeted sequencing, while long-read technologies excel at de novo assembly, resolving structural variants, and haplotype phasing [15] [17].

Sample Preparation and Quality Control: DNA/RNA quality significantly impacts sequencing results. For short-read sequencing, standard extraction methods are typically sufficient, while long-read sequencing often requires high molecular weight DNA. Quality control steps should include quantification, purity assessment, and integrity evaluation [16] [14].

Sequencing Depth and Coverage: Determine appropriate sequencing depth based on application. Variant detection typically requires 30x coverage for whole genomes, while rare variant detection may need 100x or higher. RNA-seq experiments require 20-50 million reads per sample for differential expression, with higher depth needed for isoform discovery [10].

Experimental Replicates: Include sufficient biological replicates to ensure statistical power—typically at least three for RNA-seq experiments. Technical replicates can assess protocol variability but cannot substitute for biological replicates [10].

Data Analysis Pipelines

NGS data analysis requires specialized bioinformatics tools and pipelines:

Read Processing and Quality Control: Raw sequencing data undergoes quality assessment using tools like FastQC, followed by adapter trimming and quality filtering with tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [10].

Read Alignment: Processed reads are aligned to reference genomes using aligners optimized for specific technologies: BWA-MEM or Bowtie2 for short reads, and Minimap2 or NGMLR for long reads [10].

Variant Calling: Genetic variants are identified using callers such as GATK for short reads and tools like PBSV or Sniffles for long-read structural variant detection [10].

Downstream Analysis: Specialized tools address specific applications: DESeq2 or edgeR for differential expression analysis in RNA-seq; MACS2 for peak calling in ChIP-seq; and various tools for pathway enrichment, visualization, and integration of multi-omics datasets [10].

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The evolution of NGS technologies continues at a rapid pace, with several emerging trends shaping the future of functional genomics and drug development:

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data from the same samples provides comprehensive views of biological systems. Long-read technologies facilitate this integration by simultaneously capturing sequence and modification information [14] [17].

Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Advances in single-cell technologies enable coupled measurements of genomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics from individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity and lineage relationships in development and disease [12].

Spatial Transcriptomics: Integrating NGS with spatial information preserves tissue architecture while capturing molecular profiles, enabling studies of cellular organization and microenvironment interactions [11].

Point-of-Care Sequencing: Miniaturization of sequencing technologies, particularly nanopore devices, enables real-time genomic analysis in clinical, field, and resource-limited settings, with applications in infectious disease monitoring, environmental monitoring, and rapid diagnostics [15].

Artificial Intelligence in Genomics: Machine learning and AI approaches are increasingly applied to NGS data for variant interpretation, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling, enhancing our ability to extract biological insights from complex datasets [12] [11].

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, they will further democratize genomic research and clinical application, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine through comprehensive genetic understanding.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized functional genomics research by enabling comprehensive analysis of biological systems at unprecedented resolution and scale. This high-throughput, massively parallel sequencing technology allows researchers to move beyond static DNA sequence analysis to dynamic investigations of gene expression regulation, epigenetic modifications, and protein-level interactions [5]. The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of genomics research, facilitating sophisticated studies on transcriptional regulation, chromatin dynamics, and multi-layered molecular control mechanisms that govern cellular behavior in health and disease [6].

NGS technologies have effectively bridged the gap between genomic sequence information and functional interpretation by providing powerful tools to investigate the transcriptome and epigenome in tandem. These technologies offer several advantages over traditional approaches, including higher dynamic range, single-nucleotide resolution, and the ability to profile nanogram quantities of input material without requiring prior knowledge of genomic features [19]. The integration of NGS across transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic applications has accelerated breakthroughs in understanding complex biological phenomena, from cellular differentiation and development to disease mechanisms and drug responses [20].

Transcriptomics: Comprehensive RNA Analysis

Core Methodologies and Applications

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) represents one of the most widely adopted NGS applications, providing sensitive, accurate measurement of gene expression across the entire transcriptome [21]. This approach enables researchers to detect known and novel RNA variants, identify alternative splice sites, quantify mRNA expression levels, and characterize non-coding RNA species [5]. The digital nature of NGS-based transcriptome analysis offers a broader dynamic range compared to legacy technologies like microarrays, eliminating issues with signal saturation at high expression levels and background noise at low expression levels [5].

Bulk RNA-seq analysis provides a population-average view of gene expression patterns, making it suitable for identifying differentially expressed genes between experimental conditions, disease states, or developmental stages [21]. More recently, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity within complex tissues and revealing rare cell populations that would be masked in bulk analyses [22]. Spatial transcriptomics has further expanded these capabilities by mapping gene expression patterns within the context of tissue architecture, preserving critical spatial information that informs cellular function and interactions [21].

Experimental Protocol: RNA Sequencing

Library Preparation: Total RNA is extracted from cells or tissue samples, followed by enrichment of mRNA using poly-A capture methods or ribosomal RNA depletion. The RNA is fragmented and converted to cDNA using reverse transcriptase. Adapter sequences are ligated to the cDNA fragments, and the resulting library is amplified by PCR [21] [22].

Sequencing: The prepared library is loaded onto an NGS platform such as Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000, MiSeq i100 Series, or comparable systems. For standard RNA-seq, single-end or paired-end reads of 50-300 bp are typically generated, with read depth adjusted based on experimental complexity and desired sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts [21].

Data Analysis: Raw sequencing reads are quality-filtered and aligned to a reference genome. Following alignment, reads are assembled into transcripts and quantified using tools like Cufflinks, StringTie, or direct count-based methods. Differential expression analysis is performed using statistical packages such as DESeq2 or edgeR, with functional interpretation through gene ontology (GO) enrichment, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, and gene set variation analysis (GSVA) [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics

Table 1: Essential Reagents for RNA Sequencing Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enriches for eukaryotic mRNA by binding poly-adenylated tails | mRNA sequencing, gene expression profiling |

| Ribo-depletion Reagents | Removes ribosomal RNA for total RNA sequencing | Bacterial transcriptomics, non-coding RNA discovery |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates | Library preparation for all RNA-seq methods |

| Template Switching Oligos | Enhances full-length cDNA capture | Single-cell RNA sequencing, full-length isoform detection |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tags individual molecules to correct for PCR bias | Digital gene expression counting, single-cell analysis |

| Spatial Barcoding Beads | Captures location-specific RNA sequences | Spatial transcriptomics, tissue mapping |

Epigenomics: Profiling Regulatory Landscapes

Core Methodologies and Applications

Epigenomics focuses on the molecular modifications that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, with NGS enabling genome-wide profiling of these dynamic marks [5]. Key applications include DNA methylation analysis through bisulfite sequencing or methylated DNA immunoprecipitation, histone modification mapping via chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq), and chromatin accessibility assessment using Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) [21] [20]. These approaches provide critical insights into the regulatory mechanisms that control cell identity, differentiation, and response to environmental stimuli.

NGS-based epigenomic profiling has revealed how epigenetic patterns are disrupted in various disease states, particularly cancer, where DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and global hypomethylation contribute to oncogenesis [6]. In developmental biology, these techniques have illuminated how epigenetic landscapes are reprogrammed during cellular differentiation, maintaining lineage-specific gene expression patterns. The integration of multiple epigenomic datasets enables researchers to reconstruct regulatory networks and identify key transcriptional regulators driving biological processes of interest [22].

Experimental Protocol: ATAC-Seq

Cell Preparation: Cells are collected and washed in cold PBS. For nuclei isolation, cells are lysed using a mild detergent-containing buffer. The nuclei are then purified by centrifugation and resuspended in transposase reaction buffer [21].

Tagmentation: The Tn5 transposase, pre-loaded with sequencing adapters, is added to the nuclei preparation. This enzyme simultaneously fragments accessible chromatin regions and tags the resulting fragments with adapter sequences. The reaction is incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes [21].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: The tagmented DNA is purified using a PCR cleanup kit. The library is then amplified with barcoded primers for multiplexing. After purification and quality control, the library is sequenced on an appropriate NGS platform, typically generating paired-end reads [21].

Data Analysis: Sequencing reads are aligned to the reference genome, and peaks representing open chromatin regions are called using specialized tools such as MACS2. These accessible regions are then analyzed for transcription factor binding motifs, overlap with regulatory elements, and correlation with gene expression data from complementary transcriptomic assays [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenomics

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Epigenomic Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | Fragments accessible DNA and adds sequencing adapters | ATAC-seq, chromatin accessibility profiling |

| Methylation-Specific Enzymes | Distinguishes methylated cytosines during sequencing | Bisulfite sequencing, methylome analysis |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Antibodies | Enriches for specific histone modifications or DNA-binding proteins | ChIP-seq, histone modification mapping |

| Crosslinking Reagents | Preserves protein-DNA interactions | ChIP-seq, chromatin conformation studies |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils | DNA methylation analysis, epigenetic clocks |

| Magnetic Protein A/G Beads | Captures antibody-bound chromatin complexes | ChIP-seq, epigenomic profiling |

Proteomics Integration: Connecting Genotype to Phenotype

Multiomics Approaches

While NGS primarily analyzes nucleic acids, its integration with proteomic methods has created powerful multiomics approaches for connecting genetic information to functional protein-level effects [23]. Technologies like CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing) enable simultaneous measurement of transcriptome and cell surface protein data in single cells, using oligonucleotide-labeled antibodies that can be sequenced alongside cDNA [22]. This integration provides a more comprehensive understanding of cellular states by capturing information from multiple molecular layers that may have complex, non-linear relationships.

The combination of NGS with proteomic analyses has proven particularly valuable in immunology and cancer research, where it enables detailed characterization of immune cell populations and their functional states [22]. In drug development, multiomics approaches help identify mechanistic biomarkers and therapeutic targets by revealing how genetic variants influence protein expression and function. The emerging field of spatial multiomics further extends these capabilities by mapping protein expression within tissue microenvironments, revealing how cellular interactions influence disease processes and treatment responses [23].

Experimental Protocol: CITE-Seq

Antibody-Oligo Conjugation: Antibodies against cell surface proteins are conjugated to oligonucleotides containing a PCR handle, antibody barcode, and poly(A) sequence. These custom reagents are now also commercially available from multiple vendors [22].

Cell Staining: A single-cell suspension is incubated with the conjugated antibody panel, allowing binding to cell surface epitopes. Cells are washed to remove unbound antibodies [22].

Single-Cell Partitioning: Stained cells are loaded onto a microfluidic device (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium system) along with barcoded beads containing oligo(dT) primers with cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). Each cell is co-encapsulated in a droplet with a single bead [22].

Library Preparation: Within droplets, mRNA and antibody-derived oligonucleotides are reverse-transcribed using the barcoded beads as templates. The resulting cDNA is amplified and split for separate library construction—one library for transcriptome analysis and another for antibody-derived tags (ADT) [22].

Sequencing and Data Analysis: Libraries are sequenced on NGS platforms. Bioinformatic analysis involves separating transcript and ADT reads, demultiplexing cells, and performing quality control. ADT counts are normalized using methods like centered log-ratio transformation, then integrated with transcriptomic data for combined cell type identification and characterization [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Multiomics

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Multiomics Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo-Conjugated Antibodies | Enables sequencing-based protein detection | CITE-seq, REAP-seq, protein epitope sequencing |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Labels samples with barcodes for multiplexing | Single-cell multiplexing, sample pooling |

| Viability Staining Reagents | Distinguishes live/dead cells for sequencing | Quality control in single-cell protocols |

| Cell Partitioning Reagents | Enables single-cell isolation in emulsions | Droplet-based single-cell sequencing |

| Barcoded Beads | Delivers cell-specific barcodes during RT | Single-cell RNA-seq, multiomics |

| Multimodal Capture Beads | Simultaneously captures RNA and protein data | Commercial single-cell multiomics systems |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The NGS landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping the future of transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic applications. Single-cell multiomics technologies represent a particularly promising direction, enabling simultaneous measurement of various data types from the same cell and providing unprecedented resolution for mapping cellular heterogeneity and developmental trajectories [22]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with multiomics datasets is also accelerating discoveries, with tools like Google's DeepVariant demonstrating enhanced accuracy for variant calling and AI models enabling the prediction of disease risk from complex molecular signatures [7].

Spatial biology represents another frontier, with new sequencing-based methods enabling in situ sequencing of cells within intact tissue architecture [23]. These approaches preserve critical spatial context that is lost in single-cell dissociation protocols, allowing researchers to explore complex cellular interactions and microenvironmental influences on gene expression and protein function. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they are expected to unlock routine 3D spatial studies that comprehensively assess cellular interactions in tissue microenvironments, particularly using clinically relevant FFPE samples [23].

The ongoing innovation in NGS platforms, including the development of XLEAP-SBS chemistry, patterned flow cell technology, and semiconductor sequencing, continues to drive improvements in speed, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness [5]. The recent introduction of platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq X Series, which can sequence more than 20,000 whole genomes annually at approximately $200 per genome, exemplifies how technological advances are democratizing access to large-scale genomic applications [24]. These developments, combined with advances in bioinformatics and data analysis, ensure that NGS will remain at the forefront of functional genomics research, enabling increasingly sophisticated investigations into the complex interplay between transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic regulators in health and disease.

The convergence of personalized medicine, CRISPR-based gene editing, and advanced chronic disease research is fundamentally reshaping therapeutic development and clinical applications. This transformation is underpinned by the analytical power of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) within functional genomics research, which enables the precise identification of genetic targets and the development of highly specific interventions. The global precision medicine market, valued at USD 118.52 billion in 2025, is a testament to this shift, driven by the rising prevalence of chronic diseases and technological advancements in genomics and artificial intelligence (AI) [25]. CRISPR technologies are moving beyond research tools into clinical assets, with over 150 active clinical trials as of February 2025, targeting a wide spectrum of conditions from hemoglobinopathies and cancers to cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases [26]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the key market drivers, details specific experimental protocols leveraging NGS and CRISPR, and outlines the essential toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this integrated landscape.

Market Landscape and Quantitative Analysis

Key Market Drivers and Financial Projections

The synergistic growth of personalized medicine and CRISPR-based therapies is fueled by several interdependent factors. The following tables summarize the core market drivers and their associated quantitative metrics.

Table 1: Key Market Drivers and Their Impact

| Market Driver | Description and Impact |

|---|---|

| Rising Chronic Disease Prevalence | Increasing global burden of cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders necessitates more effective, tailored treatments beyond traditional one-size-fits-all approaches [25]. |

| Advancements in Genomic Technologies | NGS and other high-throughput technologies allow for rapid, cost-effective analysis of patient genomes, facilitating the identification of disease-driving biomarkers and genetic variants [27] [24]. |

| Integration of AI and Data Analytics | AI and machine learning are critical for analyzing complex multi-omics datasets, improving guide RNA design for CRISPR, predicting off-target effects, and matching patients with optimal therapies [28] [25]. |

| Supportive Regulatory and Policy Environment | Regulatory bodies like the FDA have developed frameworks for precision medicines and companion diagnostics, while government initiatives (e.g., the All of Us Research Program) support data collection and infrastructure [27] [24]. |

Table 2: Market Size and Growth Projections for Key Converging Technologies

| Technology/Sector | 2024 Market Size | 2025 Market Size | 2033/2034 Projected Market Size | CAGR | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision Medicine (Global) | USD 101.86 Bn [25] | USD 118.52 Bn [25] | USD 463.11 Bn (2034) [25] | 16.35% (2025-2034) [25] | |

| Personalized Medicine (US) | USD 169.56 Bn [27] | - | USD 307.04 Bn (2033) [27] | 6.82% (2025-2033) [27] | |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (US) | USD 3.88 Bn [24] | - | USD 16.57 Bn (2033) [24] | 17.5% (2025-2033) [24] | |

| AI in Precision Medicine (Global) | USD 2.74 Bn [25] | - | USD 26.66 Bn (2034) [25] | 25.54% (2024-2034) [25] |

Clinical Trial Landscape for CRISPR-Based Therapies

The clinical pipeline for CRISPR therapies has expanded dramatically, demonstrating a direct application of personalized medicine principles. As of early 2025, CRISPR Medicine News was tracking approximately 250 gene-editing clinical trials, with over 150 currently active [26]. These trials span a diverse range of therapeutic areas, with a significant concentration on chronic diseases.

Table 3: Selected CRISPR Clinical Trials in Chronic Diseases (2025)

| Therapy / Candidate | Target Condition | Editing Approach | Delivery Method | Development Stage | Key Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy | Sickle Cell Disease, Beta Thalassemia | CRISPR-Cas9 | Ex Vivo | Approved (2023) | First approved CRISPR-based medicine. | [29] [26] |

| NTLA-2001 (nex-z) | Transthyretin Amyloidosis (ATTR) | CRISPR-Cas9 | LNP (in vivo) | Phase III (paused) | Paused due to a Grade 4 liver toxicity event; investigation ongoing. | [29] [28] [30] |

| NTLA-2002 | Hereditary Angioedema (HAE) | CRISPR-Cas9 | LNP (in vivo) | Phase I/II | Targets KLKB1 gene; showed ~86% reduction in disease-causing protein. | [29] [30] |

| VERVE-101 & VERVE-102 | Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia | Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | LNP (in vivo) | Phase Ib | Targets PCSK9 gene to lower LDL-C. VERVE-101 enrollment paused; VERVE-102 ongoing. | [26] [30] |

| FT819 | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | CRISPR-Cas9 | Ex Vivo CAR T-cell | Phase I | Off-the-shelf CAR T-cell therapy; showed significant disease improvement. | [28] |

| HG-302 | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) | hfCas12Max (Cas12) | AAV (in vivo) | Phase I | Compact nuclease for exon skipping; first patient dosed in 2024. | [30] |

| PM359 | Chronic Granomatous Disease (CGD) | Prime Editing | Ex Vivo HSC | Phase I (planned) | Corrects mutations in NCF1 gene; IND cleared in 2024. | [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The integration of NGS and CRISPR is a cornerstone of modern functional genomics research and therapeutic development. The following section outlines detailed protocols for key experiments.

Protocol 1: In Vivo CRISPR Therapeutic Development for a Monogenic Liver Disease

This protocol, exemplified by therapies for hATTR and HAE, details the process of developing and validating an LNP-delivered CRISPR therapy to knock out a disease-causing gene in the liver [29] [30].

1. Target Identification and Guide RNA (gRNA) Design:

- Objective: Identify a gene whose protein product drives pathology (e.g., TTR for hATTR, KLKB1 for HAE).

- Methodology:

- Use NGS (e.g., whole-genome or exome sequencing) on patient cohorts to confirm gene-disease association.

- Design multiple gRNAs targeting early exons of the gene to ensure a frameshift and complete knockout.

- Utilize AI/ML tools to predict gRNA on-target efficiency and potential off-target sites across the genome.

2. In Vitro Efficacy and Specificity Screening:

- Objective: Select the most effective and specific gRNA.

- Methodology:

- Clone gRNA candidates into a CRISPR plasmid vector containing the Cas9 nuclease.

- Transfect the constructs into relevant human hepatocyte cell lines (e.g., HepG2).

- NGS Workflow:

- Harvest genomic DNA 72 hours post-transfection.

- Amplify the target region and potential off-target sites via PCR.

- Prepare NGS libraries and sequence on a platform such as Illumina's NovaSeq X.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Use tools like BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) for sequence alignment to the reference genome (hg38) [31].

- Utilize CRISPResso2 or similar software to quantify the percentage of insertions/deletions (indels) at the target site.

- Analyze off-target sites by assessing alignment metrics and variant calling (e.g., using GATK) to confirm absence of significant editing [31].

3. In Vivo Preclinical Validation:

- Objective: Test safety and efficacy in an animal model.

- Methodology:

- Formulate the lead gRNA and Cas9 mRNA into lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) optimized for hepatocyte tropism.

- Administer a single intravenous dose of LNP-CRISPR to a humanized murine or non-human primate model.

- Monitor animals for adverse events.

- Assessment:

- Efficacy: Periodically collect plasma via venipuncture. Quantify the reduction in the target protein (e.g., TTR) using ELISA. At endpoint, harvest liver tissue to confirm editing rates via NGS.

- Safety: Perform whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on liver DNA to comprehensively assess off-target editing. Conduct histopathological examination of major organs.

4. Clinical Trial Biomarker Monitoring:

- Objective: Assess therapeutic effect in human trials.

- Methodology:

Diagram 1: In Vivo CRISPR Therapeutic Development Workflow

Protocol 2: AI-Driven Design and Functional Characterization of a Novel CRISPR Nuclease

This protocol is based on the 2025 Nature publication describing the design of OpenCRISPR-1, an AI-generated Cas9-like nuclease [32].

1. Data Curation and Model Training:

- Objective: Create a generative AI model to design novel CRISPR effector proteins.

- Methodology:

- CRISPR–Cas Atlas Construction: Systematically mine 26.2 terabases of assembled microbial genomes and metagenomes to compile a dataset of over 1 million CRISPR operons [32].

- Model Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune a large language model (e.g., ProGen2-base) on the CRISPR–Cas Atlas to learn the constraints and diversity of natural CRISPR proteins [32].

2. Protein Generation and In Silico Filtering:

- Objective: Generate and select novel nuclease sequences for testing.

- Methodology:

- Generate millions of protein sequences unconditionally or prompted with N/C-terminal of known Cas9s.

- Apply strict sequence viability filters and cluster generated sequences.

- Use AlphaFold2 to predict the 3D structure of generated proteins and select those with high confidence (mean pLDDT >80) and correct folds [32].

3. Experimental Validation in Human Cells:

- Objective: Test the function of AI-designed nucleases.

- Methodology:

- Cloning: Synthesize the gene for the top candidate (e.g., OpenCRISPR-1) and clone it into a mammalian expression plasmid. Clone a panel of gRNAs targeting various genomic loci into a companion plasmid.

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the nuclease and gRNA plasmids.

- NGS-Based Editing Analysis:

- Harvest genomic DNA 3-5 days post-transfection.

- Amplify target sites via PCR and prepare NGS libraries with unique molecular barcodes.

- Sequence using a MiSeq or similar system.

- Analyze data with a customized pipeline to calculate indel percentages and profile the spectrum of insertions and deletions.

- Specificity Assessment: Use methods like CIRCLE-seq or DISCOVER-Seq on transfected cells to identify potential off-target sites, which are then deep-sequenced to quantify off-target editing rates [32] [28].

4. Comparison to Natural Effectors:

- Objective: Benchmark the novel nuclease against existing tools (e.g., SpCas9).

- Methodology: Run the above validation steps in parallel for the novel nuclease and SpCas9, comparing editing efficiency and specificity across multiple target sites.

Diagram 2: AI-Driven CRISPR Nuclease Design Pipeline

Protocol 3: Epigenetic Editing for Neurological Disease Modeling

This protocol outlines the use of CRISPR-based epigenetic editors to manipulate gene expression in neurological disease models, as demonstrated in studies targeting memory formation and Prader-Willi syndrome [28] [33].

1. Epigenetic Editor Assembly:

- Objective: Construct a CRISPR system to modify chromatin state at a specific locus.

- Methodology:

- Clone a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) into a plasmid.

- Fuse dCas9 to an epigenetic effector domain (e.g., p300 core acetyltransferase for activation [CRISPRa] or KRAB repressor domain for repression [CRISPRi]).

- Clone a gRNA specific to the promoter of the target gene (e.g., Arc for memory, Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting control region).

2. In Vitro Validation in Neuronal Cells:

- Objective: Confirm the system's functionality.

- Methodology:

- Transfect the dCas9-effector and gRNA plasmids into human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neuronal progenitor cells.

- NGS-Based Validation:

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq): Perform 7 days post-transfection to assess changes in chromatin accessibility at the target site.

- RNA-seq: Perform to analyze genome-wide changes in gene expression, confirming up/downregulation of the target gene and identifying any unintended transcriptomic effects.

- Differentiate corrected iPSCs into hypothalamic organoids for further study [28].

3. In Vivo Delivery and Analysis in Animal Models:

- Objective: Modulate gene function in the living brain.

- Methodology:

- Package the epigenetic editor into an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector with a neuron-specific promoter.

- Stereotactically inject the AAV into the target brain region (e.g., hippocampus) of a mouse model.

- Functional and Molecular Analysis:

- Behavioral Assays: Conduct tests (e.g., fear conditioning for memory) to assess functional outcomes.

- NGS Analysis: Harvest brain tissue after behavioral testing. Use ATAC-seq and RNA-seq on isolated nuclei/RNA from the injected region to correlate epigenetic and transcriptomic changes with behavior.

- Reversibility: Express anti-CRISPR proteins in a subsequent AAV injection to demonstrate the reversibility of the epigenetic modification and its functional effects [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and tools essential for conducting research at the convergence of NGS, CRISPR, and personalized medicine.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Category | Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Editing Machinery | Cas9 Nuclease (SpCas9) | Creates double-strand breaks in DNA for gene knockout. | Prototypical nuclease for initial proof-of-concept studies. |

| Base Editors (ABE, CBE) | Chemically converts one DNA base into another without double-strand breaks. | Correcting point mutations (e.g., sickle cell disease) [28]. | |

| Prime Editors | Uses a reverse transcriptase to "write" new genetic information directly into a target site. | Correcting pathogenic COL17A1 variants for epidermolysis bullosa [28]. | |

| dCas9-Epigenetic Effectors (dCas9-p300, dCas9-KRAB) | Modifies chromatin state to activate or repress gene expression. | Bidirectionally controlling memory formation via Arc gene expression [28]. | |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery of CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) or mRNA to target organs (e.g., liver). | Delivery of NTLA-2001 for hATTR amyloidosis [29] [30]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | In vivo delivery of CRISPR constructs to target tissues, including the CNS. | Delivery of epigenetic editors to the brain for neurological disease modeling [33]. | |

| NGS & Analytical Tools | Illumina NovaSeq X Series | High-throughput sequencing for whole genomes, exomes, and transcriptomes. | Primary tool for WGS-based off-target assessment and RNA-seq. |

| BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) | Aligns sequencing reads to a reference genome. | First step in most NGS analysis pipelines for variant discovery [31]. | |

| GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) | Variant discovery and genotyping from NGS data. | Used for rigorous identification of single nucleotide variants and indels [31]. | |

| DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform | Hardware-accelerated secondary analysis of NGS data (alignment, variant calling). | Integrated with Illumina systems for rapid on-instrument data processing [24]. | |

| AI & Bioinformatics | Protein Language Models (e.g., ProGen2) | AI models trained on protein sequences to generate novel, functional proteins. | Design of novel CRISPR effectors like OpenCRISPR-1 [32]. |

| gRNA Design & Off-Target Prediction Tools | In silico prediction of gRNA efficiency and potential off-target sites. | Initial screening of gRNAs to select the best candidates for experimental testing. | |

| Cell Culture & Models | Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-derived cells that can be differentiated into various cell types. | Modeling rare genetic diseases; source for ex vivo cell therapies. |

| Organoids | 3D cell cultures that mimic organ structure and function. | Testing CRISPR corrections in a physiologically relevant model (e.g., hypothalamic organoids for PWS) [28]. | |

| Fluorene-13C6 | Fluorene-13C6, CAS:1189497-69-5, MF:C13H10, MW:172.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Albaconazole-d3 | Albaconazole-d3, MF:C20H16ClF2N5O2, MW:434.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

NGS in Action: Core Methodologies and Breakthrough Applications in Research

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics, enabling genome-wide quantification of gene expression and the analysis of complex RNA processing events such as alternative splicing. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to RNA-seq methodologies, focusing on differential expression analysis and the demarcation of alternative splicing events. We detail experimental protocols, computational workflows, and normalization techniques essential for robust data interpretation. Furthermore, we explore the application of long-read sequencing in distinguishing cis- and trans-directed splicing regulation. Framed within the broader context of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in functional genomics, this review equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to design and execute rigorous RNA-seq studies, extract meaningful biological insights, and understand their implications for disease mechanisms and therapeutic discovery.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has transformed genomics from a specialized pursuit into a cornerstone of modern biological research and clinical diagnostics [7] [12]. Unlike first-generation Sanger sequencing, NGS employs a massively parallel approach, processing millions of DNA fragments simultaneously to deliver unprecedented speed and cost-efficiency [12]. The cost of sequencing a whole human genome has plummeted from billions of dollars to under \$1,000, making large-scale genomic studies feasible [7]. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a pivotal NGS application that allows for the comprehensive, genome-wide inspection of transcriptomes by converting RNA populations into complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries that are subsequently sequenced [34].

The power of RNA-seq lies in its ability to quantitatively address a diverse array of biological questions. Key applications include:

- Differential Gene Expression (DGE): Identifying genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated between conditions, such as diseased versus healthy tissues or treated versus control samples [34].

- Alternative Splicing (AS) Analysis: Detecting and quantifying the inclusion or exclusion of exons and introns, which generates multiple mRNA isoforms from a single gene and greatly expands the functional proteome [35] [36].

- Variant Discovery: Identifying individual-specific genetic mutations from transcriptomic data, which can reveal allele-specific expression or somatic mutations in cancers [37] [31].

- Cell-Type Deconvolution: Estimating the cellular composition of complex tissues from bulk RNA-seq data using computational methods and single-cell reference datasets [37].

This whitepaper provides a detailed guide to the core principles and methodologies of RNA-seq data analysis, with a particular emphasis on differential expression and the rapidly advancing field of alternative splicing analysis using long-read technologies.

Core Principles and Experimental Design

From Sequencing to Expression Quantification

The RNA-seq workflow begins with the conversion of RNA samples into a library of cDNA fragments to which adapters are ligated, enabling sequencing on platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq X [7] [12]. The primary output is millions of short DNA sequences, or reads, which represent fragments of the RNA molecules present in the original sample [34]. A critical challenge in converting these reads into a gene expression matrix involves two levels of uncertainty: first, determining the most likely transcript of origin for each read, and second, converting these read assignments into a count of expression that models the inherent uncertainty in the process [38].

Two primary computational approaches address this:

- Alignment-Based Mapping: Tools like STAR or HISAT2 perform splice-aware alignment of reads to a reference genome, recording the exact coordinates of matches. This generates SAM/BAM format files and is valuable for generating comprehensive quality control metrics [38] [34].

- Pseudo-Alignment: Tools such as Salmon and kallisto use faster, probabilistic methods to determine the locus of origin without base-level alignment. These are highly efficient for large datasets and simultaneously handle read assignment and quantification [38] [34].

A recommended best practice is a hybrid approach: using STAR for initial alignment to generate QC metrics, followed by Salmon in its alignment-based mode to perform statistically robust expression quantification [38]. The final step is read quantification, where tools like featureCounts tally the number of reads mapped to each gene, producing a raw count matrix that serves as the foundation for all subsequent differential expression analysis [34].

Foundational Experimental Design

The reliability of conclusions drawn from an RNA-seq experiment hinges on a robust experimental design. Two key parameters are biological replication and sequencing depth.

- Biological Replicates: These are essential for estimating biological variability and ensuring statistical power. While differential expression analysis is technically possible with two replicates, the ability to control false discovery rates is greatly reduced. Three replicates per condition is often considered the minimum standard, though more are recommended when biological variability is high [34].

- Sequencing Depth: This refers to the number of reads sequenced per sample. Deeper sequencing increases sensitivity for detecting lowly expressed genes. For standard DGE analysis, approximately 20–30 million reads per sample is often sufficient [34]. The required depth can be estimated using power analysis tools like Scotty and should be guided by pilot data or existing literature in similar biological systems.

A Technical Guide to Differential Expression Analysis

Preprocessing and Normalization

Once a raw count matrix is obtained, several preprocessing steps are required before statistical testing. Data cleaning involves filtering out genes with low or no expression across the majority of samples to reduce noise. A common threshold is to keep only genes with counts above zero in at least 80% of the samples in the smallest group [39].

Normalization is critical because raw counts are not directly comparable between samples. The total number of reads obtained per sample, known as the sequencing depth, differs between libraries. Furthermore, a few highly expressed genes can consume a large fraction of reads in a sample, skewing the representation of all other genes—a bias known as library composition [34]. Various normalization methods correct for these factors to a different extent, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Common Normalization Methods for RNA-seq Data

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts per Million) | Yes | No | No | No |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| median-of-ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values, edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

For differential expression analysis, the normalization methods implemented in specialized tools like DESeq2 (median-of-ratios) and edgeR (TMM) are recommended because they effectively correct for both sequencing depth and library composition differences, which is essential for valid statistical comparisons [34] [39].

Statistical Testing for Differential Expression

The core of DGE analysis involves testing, for each gene, the null hypothesis that its expression does not vary between conditions. This is performed using statistical models that account for the count-based nature of the data. A standard workflow, as implemented in tools like limma-voom, DESeq2, and edgeR, involves the following steps [38] [39]:

- Normalization: Apply a method like TMM to the raw counts.

- Model Fitting: Fit a generalized linear model (GLM) to the normalized counts for each gene. The model includes the experimental conditions as predictors.

- Statistical Testing: Perform hypothesis testing (e.g., a moderated t-test in

limma) to compute a p-value and a false discovery rate (FDR) for each gene, indicating the significance of the expression change. - Result Interpretation: The primary output is a table of genes including:

- logFC: The log2-fold change in expression between conditions.

- P-value: The probability of observing the data if the null hypothesis is true.

- Adjusted P-value (FDR): A p-value corrected for multiple testing to control the rate of false positives.

The following workflow diagram (Figure 1) outlines the key steps in a comprehensive RNA-seq analysis, from raw data to biological insight.

Figure 1: RNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard steps for processing bulk RNA-seq data, from raw sequencing files to the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and biological interpretation.

Advanced Analysis: Demarcating Alternative Splicing

The Complexity of Splicing Regulation

Alternative splicing (AS) is a critical post-transcriptional mechanism that enables a single gene to produce multiple protein isoforms, substantially expanding the functional capacity of the genome. Over 95% of multi-exon human genes undergo AS, generating vast transcriptomic diversity [35]. Splicing is regulated by the interplay between cis-acting elements (DNA sequence features) and trans-acting factors (e.g., RNA-binding proteins). Disruptions in this regulation are a primary link between genetic variation and disease [36].

A key challenge is distinguishing whether an AS event is primarily directed by cis- or trans- mechanisms. cis-directed events are those where genetic variants on a haplotype directly influence splicing patterns (e.g., by creating or destroying a splice site). In contrast, trans-directed events show no linkage to the haplotype and are controlled by the cellular abundance of trans-acting factors [36].

Long-Read RNA-seq and the isoLASER Method

Short-read RNA-seq struggles to accurately resolve full-length transcript isoforms, particularly for complex genes. Long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio Sequel II, Oxford Nanopore) are game-changers for splicing analysis because they sequence entire RNA molecules in a single pass [36]. This allows for the direct observation of haplotype-specific splicing when combined with genotype information.

A novel computational method, isoLASER, leverages long-read RNA-seq to clearly segregate cis- and trans-directed splicing events in individual samples [36]. The method performs three major tasks:

- De novo variant calling from long-read data with high precision.

- Gene-level phasing of variants to assign reads to maternal or paternal haplotypes.

- Linkage testing between phased haplotypes and alternatively spliced exonic segments to quantify allelic imbalance in splicing.

Application of isoLASER to data from human and mouse revealed that while global splicing profiles cluster by tissue type (a trans-driven pattern), the genetic linkage of splicing is highly individual-specific, underscoring the pervasive role of an individual's genetic background in shaping their transcriptome [36]. This demarcation is crucial for understanding the genetic basis of disease, as it helps prioritize cis-directed events that are more directly linked to genotype.