A Comprehensive Guide to Benchmarking Differential Gene Expression Tools: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review synthesizes current methodologies and best practices for benchmarking differential gene expression (DGE) analysis tools across diverse transcriptomic data types.

A Comprehensive Guide to Benchmarking Differential Gene Expression Tools: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current methodologies and best practices for benchmarking differential gene expression (DGE) analysis tools across diverse transcriptomic data types. We explore foundational principles of computational benchmarking, methodological approaches for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data, troubleshooting common analytical challenges, and validation frameworks for performance assessment. Drawing from recent benchmarking studies, we provide evidence-based recommendations for tool selection across various experimental designs, emphasizing robust statistical practices to enhance reproducibility in biomedical research. This guide serves researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in navigating the complex landscape of DGE analysis tools for biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification.

The Fundamentals of DGE Benchmarking: Principles, Metrics, and Experimental Design

Defining Benchmarking Scope and Purpose in DGE Analysis

Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis represents a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, enabling researchers to identify genes with statistically significant expression changes between biological conditions. The expanding landscape of statistical methods and normalization techniques has created an urgent need for comprehensive benchmarking studies to guide tool selection and experimental design. Well-defined benchmarking provides the critical framework for evaluating the performance, limitations, and optimal application domains of diverse DGE methodologies. Establishing standardized benchmarking protocols ensures that performance comparisons reflect true biological insights rather than methodological artifacts, thereby accelerating scientific discovery and therapeutic development in genomics research.

The Critical Importance of Benchmarking in DGE Analysis

Benchmarking in DGE analysis serves multiple essential functions for the research community. It provides empirical evidence for selecting appropriate tools based on specific experimental conditions, data characteristics, and research questions. For instance, performance characteristics can vary dramatically between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data, with methods like ALDEx2 demonstrating high precision for bulk data while mixed-effects models like NEBULA excel with single-cell data incorporating multiple biological replicates [1] [2]. Furthermore, benchmarking reveals how methodological performance depends on specific data parameters including sequencing depth, proportion of differentially expressed genes, presence of batch effects, and sample size [3] [4].

Comprehensive benchmarking also drives methodological improvements by identifying limitations in current approaches and establishing performance baselines for new method development. The rigorous evaluation of 46 integration workflows for single-cell DGE analysis by Tran et al. exemplifies how benchmarking can reveal unexpected patterns, such as the finding that batch-effect corrected data rarely improves analysis for sparse single-cell data [3]. Finally, properly conducted benchmarking studies enhance reproducibility by establishing best practices and highlighting potential pitfalls in analytical workflows, thereby strengthening the reliability of transcriptomic research findings.

Defining the Benchmarking Scope

Performance Metrics

A critical first step in benchmarking involves selecting appropriate performance metrics that capture different aspects of methodological performance. The table below summarizes key metrics used in comprehensive DGE benchmarking studies:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for DGE Benchmarking

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Classification Accuracy | Area Under ROC Curve (AUC), Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR/PR AUC), Partial AUC (pAUC) | Measures overall ability to distinguish truly differentially expressed genes from non-differential genes; pAUC focuses on relevant high-sensitivity regions [5] [4]. |

| Error Control | True False Discovery Rate (FDR), False Positive Counts (FPC), Type I Error Rate | Assesses reliability of significant findings and control of false positives under null hypothesis [4] [2]. |

| Power and Sensitivity | True Positive Rate (TPR), Power, Recall | Measures ability to detect truly differentially expressed genes [4]. |

| Robustness and Reliability | Reproducibility, Effect Size Bias (FC Bias), Tolerance to Missing Values | Evaluates consistency across replicates and robustness to data imperfections [5] [2]. |

Experimental Conditions and Data Characteristics

Benchmarking scope must encompass diverse experimental conditions that reflect real-world analytical challenges:

- Sample Size and Replication: Evaluating performance across varying sample sizes (from small pilot studies to large cohorts) and properly accounting for biological versus technical replicates [2] [6].

- Data Type and Technology: Distinct performance considerations for bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, proteomics data, and spatial transcriptomics, each with unique statistical characteristics [5] [3] [2].

- Data Quality Parameters: Sequencing depth, sparsity (zero-inflation), batch effects, and missing data patterns significantly impact tool performance [3] [4].

- Biological Context: Proportion of truly differentially expressed genes, effect sizes (fold changes), balanced versus unbalanced differential expression, and presence of covariates [4] [2].

Methodological Diversity

Comprehensive benchmarking should include multiple methodological approaches:

- Normalization Strategies: Methods like DESeq's median ratio, TMM (edgeR), and log-ratio transformations (ALDEx2) that address compositionality and library size differences [1] [7].

- Statistical Frameworks: Negative binomial models (DESeq2, edgeR), linear models (limma-voom), mixed-effects models (NEBULA), and non-parametric methods [4] [2] [6].

- Study Design Adaptations: Methods specific to longitudinal data (RolDE), multi-condition experiments, and integrated analysis across batches [5] [3].

Experimental Design and Benchmarking Protocols

Data Generation Strategies

Benchmarking requires appropriate data with known ground truth for rigorous performance evaluation:

Table 2: Data Generation Methods for DGE Benchmarking

| Data Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Experiments | Known quantities of synthetic RNA sequences spiked into biological samples [5] [4] | Provides exact fold-change expectations; models technical variability | May not capture full biological complexity; limited dynamic range |

| Fully Simulated Data | Computer-generated data based on statistical models (e.g., negative binomial) [4] [2] | Enables controlled evaluation of specific parameters; unlimited replicates | Model assumptions may not fully reflect real data characteristics |

| Semi-Simulated Data | Real data with simulated differential expression signals added [5] [3] | Preserves characteristics of real data while controlling ground truth | Complex implementation; potential interactions with real signal |

| Experimental Gold Standards | Well-characterized biological datasets with validated gene expression differences [1] [8] | Represents real biological scenarios; includes all technical complexities | Limited availability; may not represent all research contexts |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

A robust benchmarking protocol for DGE tools incorporates multiple experimental scenarios:

Protocol 1: Basic Performance Evaluation

- Generate simulated RNA-seq count data using negative binomial distribution with parameters estimated from real biological replicates [4]

- Introduce differential expression for a specified proportion of genes (typically 10-20%) with defined fold changes [4]

- Apply each DGE method with appropriate normalization procedures

- Compare reported significant genes to known ground truth using multiple performance metrics

- Repeat across varying sample sizes (3-20 per group) and sequencing depths

Protocol 2: Robustness to Real-World Data Challenges

- Incorporate batch effects of varying magnitudes using real datasets or realistic simulation [3]

- Introduce different patterns of missing data or zero-inflation relevant to single-cell data [3] [2]

- Evaluate performance with unbalanced experimental designs and confounding covariates [2]

- Test sensitivity to outliers through deliberate introduction of extreme values [4]

Protocol 3: Specialized Experimental Designs

- For longitudinal data: Generate time-series data with varying trajectory patterns (linear, sigmoidal, polynomial) and evaluate methods like RolDE, BETR, and Timecourse [5]

- For single-cell data: Implement multi-subject, multi-condition simulations that account for subject-to-subject variation and hierarchical data structure [2]

- For multi-batch studies: Evaluate batch effect correction methods and covariate modeling approaches using balanced study designs [3]

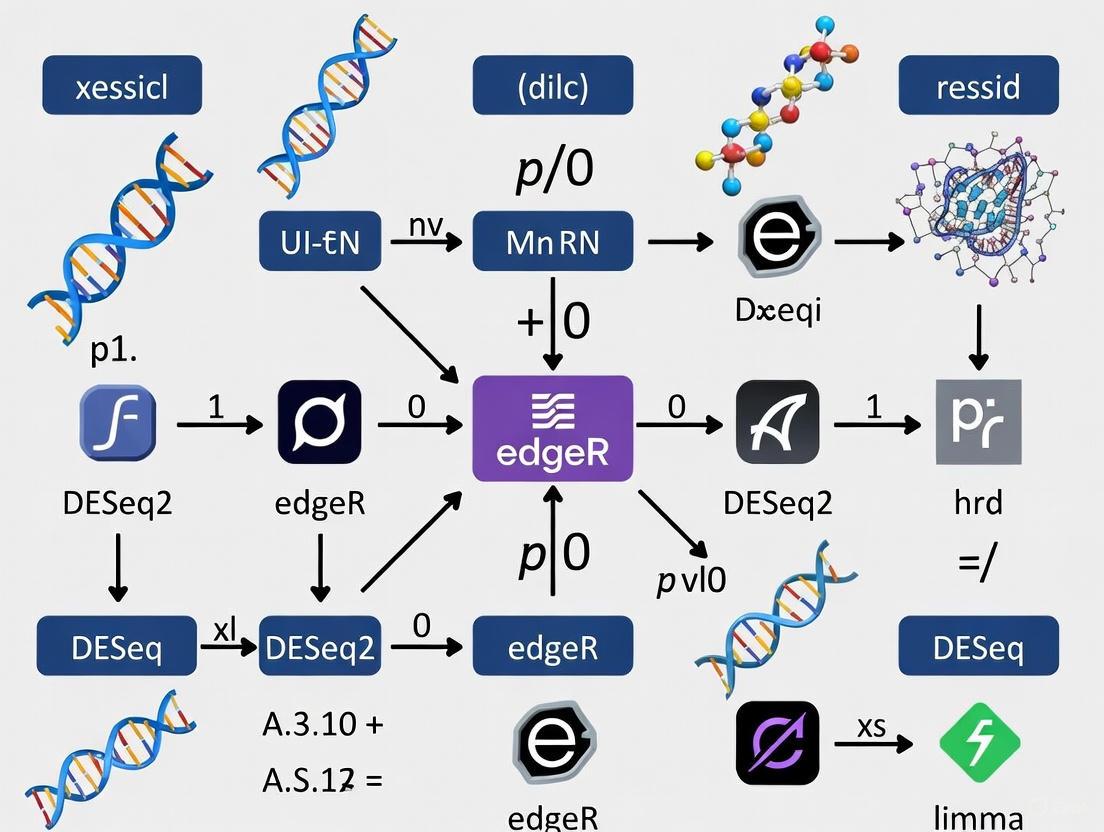

Visualization of Benchmarking Workflows

DGE Benchmarking Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for benchmarking differential gene expression analysis tools, from objective definition through data generation, method evaluation, and final interpretation.

Performance Comparison Across DGE Methods

Synthesizing results from multiple benchmarking studies reveals consistent patterns in methodological performance:

Table 3: Comparative Performance of DGE Method Categories

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Optimal Application Context | Key Strengths | Important Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial-Based | DESeq2, edgeR (exact test & GLM), edgeR robust [4] | Bulk RNA-seq with biological replicates; standard experimental designs | Overall good performance across conditions; DESeq2 shows steady performance regardless of outliers, sample size, or proportion of DE genes [4] | Performance can depend on proportion of DE genes; some edgeR variants yield more false positives [4] |

| Linear Model-Based | limma-voom (TMM & quantile), limma-trend, ROTS [3] [4] | Bulk RNA-seq with small sample sizes; single-cell pseudobulk approaches | Good performance for most cases; ROTS excels with unbalanced DE genes and large numbers of DE genes [4] | Relatively lower power compared to NB methods; voom performance decreases with increased proportion of DE genes [4] |

| Log-Ratio Transformation | ALDEx2 [1] | Data with compositional characteristics; meta-genomics and RNA-seq | High precision (few false positives); applicable to multiple sequencing modalities [1] | Performance depends on log-ratio transformation choice; requires certain assumptions [1] |

| Mixed Effects Models | NEBULA, glmmTMB [2] | Single-cell data with multiple subjects; hierarchical study designs | Accounts for subject-level variation; avoids pseudoreplication; outperforms for multi-subject scRNA-seq [2] | Computationally intensive for large datasets [6] |

| Distribution-Based | distinct, IDEAS, BSDE [6] | Single-cell data exploring beyond mean expression | Detects differences in distribution properties beyond mean expression [6] | Less established for standard differential expression analysis [6] |

| Longitudinal Methods | RolDE, BETR, Timecourse [5] | Time-course experiments with multiple time points | RolDE performs best with various trend types and missing values; good reproducibility [5] | Many longitudinal methods produce high false positives with small time points (<8) [5] |

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for DGE Benchmarking

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Splatter [3] | Simulates scRNA-seq count data based on negative binomial model | Generating realistic single-cell data for method evaluation | Allows parameter estimation from real data; models multiple cell types and differential expression |

| MSMC-Sim [2] | Multi-subject, multi-condition simulator for scRNA-seq | Benchmarking methods that account for subject-level variation | Captures subject-to-subject variation; accommodates covariates in simulation |

| polyester [1] | Simulates RNA-seq data as raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) | Evaluating impact of alignment and quantification methods on downstream analysis | Simulates data where relative abundances follow negative binomial model |

| PEREGGRN [8] | Benchmarking platform for expression forecasting methods | Evaluating prediction of genetic perturbation effects on transcriptome | Includes 11 quality-controlled perturbation datasets; configurable benchmarking software |

| muscat [6] | Implements mixed-effects models and pseudobulk methods for single-cell data | Multi-sample, multi-condition single-cell analysis | Provides multiple methodological approaches within unified framework |

| ZINB-WaVE [3] | Provides observation weights for zero-inflated data | Enabling bulk RNA-seq tools to handle single-cell data | Weights help discriminate biological vs. technical zeros; performance deteriorates with very low depths |

Effective benchmarking of differential gene expression analysis tools requires carefully defined scope, appropriate performance metrics, and standardized experimental protocols that reflect diverse biological scenarios. The expanding complexity of transcriptomic technologies demands continuous evolution of benchmarking frameworks to address emerging challenges including multi-omics integration, spatial transcriptomics, and large-scale single-cell atlases. Future benchmarking efforts should prioritize development of community standards for evaluation metrics, increased accessibility of gold standard datasets, and systematic assessment of computational efficiency alongside statistical performance. By establishing rigorous, comprehensive benchmarking practices, the scientific community can ensure continued advancement in transcriptomic data analysis methodologies, ultimately accelerating discoveries in basic biology and therapeutic development.

In the field of genomics and differential gene expression (DGE) analysis, the evaluation of computational tools and experimental protocols extends far beyond simple accuracy measurements. The performance of these methods directly impacts biological discovery, clinical diagnostic reliability, and drug development outcomes. For DGE tools, benchmarking requires a sophisticated understanding of multiple performance metrics that collectively capture different aspects of predictive capability, particularly when distinguishing subtle expression changes that characterize clinically relevant biological differences [9].

The fundamental challenge in benchmarking lies in the fact that no single metric provides a complete picture of tool performance. Sensitivity and specificity form the foundational binary classification metrics, while precision, recall, F1-score, AUC-ROC, and correlation coefficients offer complementary perspectives essential for comprehensive evaluation [10] [11]. The choice of appropriate metrics becomes especially critical when dealing with imbalanced datasets, which are commonplace in genomic studies where true positive cases are often rare compared to true negatives [11]. Furthermore, recent large-scale benchmarking initiatives have revealed that optimal metric selection depends heavily on the specific biological context and the nature of the expression changes being studied [8] [9].

Foundational Metrics: Definitions and Relationships

Core Metric Definitions

The evaluation of binary classification performance begins with four fundamental outcomes derived from confusion matrices: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) [10] [11]. These basic building blocks form the basis for calculating the most essential performance metrics:

- Sensitivity (Recall/True Positive Rate): Measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified: ( \frac{TP}{TP + FN} ) [11]

- Specificity (True Negative Rate): Measures the proportion of actual negatives correctly identified: ( \frac{TN}{TN + FP} ) [11]

- Precision (Positive Predictive Value): Measures the proportion of positive identifications that are actually correct: ( \frac{TP}{TP + FP} ) [10]

- F1-Score: Represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall: ( 2 \times \frac{Precision \times Recall}{Precision + Recall} ) [10]

These metrics are visually summarized and their relationships depicted in the following diagnostic metric decision diagram:

Metric Selection Criteria

The choice between emphasizing sensitivity-specificity versus precision-recall depends primarily on dataset characteristics and research objectives. Balanced datasets with approximately equal positive and negative cases are well-served by sensitivity and specificity, as both true positive and true negative rates carry comparable importance [11]. However, genomic contexts frequently involve significant class imbalance, such as in variant calling where true variants are vastly outnumbered by non-variant sites [11]. In these situations, precision and recall provide more meaningful assessment because they focus specifically on the positive class (e.g., truly differentially expressed genes) while ignoring the potentially misleading influence of numerous true negatives [11].

The inherent trade-off between sensitivity and specificity manifests clearly when adjusting classification thresholds. As sensitivity increases, specificity typically decreases, and vice versa [11]. This relationship necessitates careful threshold selection based on the relative costs of false positives versus false negatives for each specific application. In clinical diagnostics, for instance, high sensitivity is often prioritized to avoid missing true cases, while in preliminary screening tests, high specificity might be preferred to reduce false alarms [11].

Advanced Metrics and Analysis Frameworks

Comprehensive Metric Taxonomy

Beyond the fundamental metrics, sophisticated benchmarking of differential gene expression tools requires additional specialized measurements that capture different performance dimensions:

- Area Under ROC Curve (AUC-ROC): Measures the overall classification performance across all possible thresholds, providing a single scalar value representing the probability that a random positive example is ranked higher than a random negative example [10].

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE): Regression-based metrics used particularly in expression forecasting to quantify the magnitude of prediction errors in continuous expression values [8].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): A metric employed in large-scale RNA-seq benchmarking to quantify the ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise, especially important for detecting subtle differential expression [9].

- Spearman Correlation: Assesses the rank-order relationship between predicted and actual expression values, capturing monotonic associations without assuming linearity [8].

Recent benchmarking efforts have revealed that different metrics can yield substantially different conclusions about method performance, emphasizing the importance of metric selection aligned with specific biological questions and applications [8].

Integrated Assessment Frameworks

Comprehensive tool evaluation requires multi-dimensional assessment frameworks that incorporate multiple metric types. The PEREGGRN benchmarking platform, for instance, employs a tiered metric approach including: (1) standard performance metrics (MAE, MSE, Spearman correlation), (2) metrics focused on the most differentially expressed genes, and (3) cell type classification accuracy for reprogramming studies [8]. This stratified approach acknowledges that different applications prioritize different aspects of performance.

Large-scale consortium-led efforts like the Quartet project have developed sophisticated assessment frameworks that combine multiple "ground truth" reference sets, including built-in truths (spike-in controls with known ratios) and external validation datasets (TaqMan measurements) [9]. This multi-faceted approach enables robust characterization of RNA-seq performance across accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity dimensions.

Experimental Benchmarking Data from Recent Studies

Large-Scale Benchmarking Insights

Recent multi-center studies have generated comprehensive quantitative data on the performance of differential gene expression methodologies. The 2024 Quartet project, encompassing 45 laboratories and 140 bioinformatics pipelines, revealed substantial inter-laboratory variations in detecting subtle differential expression [9]. The study found that performance metrics were significantly influenced by both experimental factors (mRNA enrichment strategies, library strandedness) and computational factors (normalization methods, gene annotations).

Table 1: Performance Metrics from Multi-Center RNA-Seq Benchmarking

| Assessment Category | Specific Metric | Performance Range | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | PCA-based Signal-to-Noise Ratio | 0.3-37.6 (Quartet) vs. 11.2-45.2 (MAQC) | Library preparation, sequencing depth |

| Expression Accuracy | Correlation with TaqMan data | 0.738-0.856 (MAQC) vs. 0.835-0.906 (Quartet) | mRNA enrichment, strandedness |

| Spike-In Recovery | ERCC correlation | 0.828-0.963 | Normalization methods, quantification tools |

| DEG Reproducibility | Inter-lab concordance | Significant variation | Bioinformatics pipelines, gene annotation |

The benchmarking demonstrated that quality assessments based solely on samples with large biological differences (like MAQC references) may not ensure accurate detection of clinically relevant subtle expression changes, highlighting the need for more sensitive metric frameworks [9].

Method-Specific Performance Comparisons

The 2025 PEREGGRN expression forecasting benchmark evaluated diverse machine learning methods against simple baselines across 11 large-scale perturbation datasets [8]. This systematic comparison revealed that only a minority of specialized methods consistently outperformed simple dummy predictors (mean or median expression), emphasizing the challenge of genuine expression forecasting.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Genomic Selection Methods

| Method Type | Model Name | Key Characteristics | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression-Based | RC (Bayesian BLP) | Standard genomic best linear unbiased predictor | Baseline performance |

| Regression-Optimal | RO | Optimized threshold balancing sensitivity/specificity | Superior F1-score (9.62-60.87% improvement) |

| Bayesian Classification | B (Threshold Bayesian Probit) | Binary classification with 0.5 threshold | Lower sensitivity |

| Bayesian-Optimal | BO | Optimized probability threshold | Second-best performance after RO |

| Threshold-Based | R | RC model with classification threshold | Intermediate performance |

The RO (Regression Optimal) method emerged as particularly effective, outperforming other models in F1-score (by 9.62-60.87%), Kappa coefficient (by 3.95-52.18%), and sensitivity (by 86.20-250.41%) across five real datasets [12]. This superior performance was attributed to its optimized threshold selection that balances sensitivity and specificity.

Experimental Protocols for Tool Benchmarking

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

Robust evaluation of differential gene expression tools requires carefully controlled experimental designs and analysis protocols. The following workflow diagram illustrates key stages in a comprehensive benchmarking pipeline:

The Quartet project implemented a rigorous benchmarking protocol utilizing well-characterized RNA reference materials from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines, spiked with External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) RNA controls at defined ratios [9]. This design incorporated multiple types of "ground truth," including built-in truths (known spike-in ratios and sample mixtures) and external reference datasets (TaqMan validation measurements). Each of the 45 participating laboratories processed identical reference samples using their local RNA-seq workflows, generating 1080 libraries representing diverse experimental protocols and sequencing platforms [9].

Differential Expression Analysis Pipeline

For the bioinformatics comparison, researchers applied 140 distinct analysis pipelines systematically varying each processing step: two gene annotations (GENCODE, RefSeq), three genome alignment tools (HISAT2, STAR, others), eight quantification tools (featureCounts, Salmon, etc.), six normalization methods (TPM, FPKM, and others), and five differential analysis tools (DESeq2, edgeR, etc.) [9]. This comprehensive approach enabled precise identification of variability sources throughout the analytical chain.

The DEAPR (Differential Expression and Pathway Ranking) methodology exemplifies a specialized bioinformatic approach for evaluating RNA-sequencing results, particularly with small sample sizes [13]. DEAPR employs two novel gene selection methods: Differential Expression of Low-Variability (DELV) genes and Separation of Ranges by Minimum and Maximum (SRMM) values. The method selects protein-coding genes with either absolute fold-change differences ≥2 between average FPKMs (for DELV genes) or absolute SRMM ≥2.0 (for genes failing DELV but meeting SRMM criteria), then ranks genes by both fold change (90% weight) and FPKM difference (10% weight) [13].

Critical Experimental Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RNA-Seq Benchmarking

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Application in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet RNA samples (M8, F7, D5, D6) | Provide samples with subtle biological differences for sensitivity assessment |

| Spike-In Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | Built-in truth for absolute quantification and ratio recovery |

| Validation Assays | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Orthogonal validation method for expression measurements |

| Library Prep Kits | Diverse commercial kits (Illumina, etc.) | Assessing protocol-specific performance variations |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, HiSeq, etc. | Evaluating platform-specific effects on metrics |

| Reference Genomes | GRCh38, GENCODE annotations | Standardized alignment and quantification references |

Bioinformatics Tools and Databases

The benchmarking studies evaluated numerous computational tools and resources critical for differential expression analysis [9]. Alignment tools including HISAT2 and STAR were assessed for their impact on downstream metrics [13]. Quantification methods ranging from count-based (featureCounts) to transcript-level (Salmon) were compared for their effects on sensitivity and specificity. Normalization approaches including TPM, FPKM, and size-factor methods (DESeq2, edgeR) were systematically evaluated for their ability to improve cross-sample comparability [9].

Specialized resources like the GeneAnalytics pathway analysis platform with its PathCards unification database provided functional interpretation capabilities, with pathway scores calculated using binomial distribution models corrected for false discovery rates [13]. These bioinformatics resources formed the foundation for comprehensive performance assessment across multiple analytical dimensions.

Implications for Research and Diagnostic Applications

The rigorous benchmarking of performance metrics has profound implications for both basic research and clinical applications. In drug development, where accurate identification of differentially expressed genes can inform target discovery and mechanism of action studies, understanding the sensitivity and specificity limitations of analytical methods is crucial for minimizing false leads and optimizing resource allocation [14]. The finding that subtle differential expression detection shows greater inter-laboratory variation than large expression changes underscores the importance of standardized protocols for clinical diagnostic applications [9].

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing and other high-resolution transcriptomic technologies further amplifies the need for sophisticated metric frameworks that can account for cellular heterogeneity, technical noise, and sparse expression patterns [14]. As expression forecasting methods evolve toward predicting effects of novel genetic perturbations [8], the development of appropriate performance metrics will remain essential for translating computational predictions into biological insights and clinical applications.

In the rigorous field of genomics, benchmarking computational methods is essential for driving scientific progress. A foundational aspect of this process is the use of gold standard datasets, which provide a known ground truth against which the performance of analytical tools is evaluated. These reference data broadly fall into two categories: experimentally derived and simulated datasets. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two paradigms, focusing on their application in benchmarking differential gene expression (DGE) tools, to help researchers and drug development professionals make informed methodological choices.

Defining Gold Standard Datasets

A gold standard dataset is a curated collection of data that serves as a benchmark for evaluating the performance of computational models and algorithms [15]. For the evaluation to be credible, this dataset must be considered a source of ground truth—the definitive answer key against which predictions are compared [15]. The core attributes of a high-quality gold standard include:

- Accuracy: Data must be obtained from qualified sources and be free from errors and inconsistencies [15].

- Completeness: The dataset should cover all relevant aspects of the real-world phenomenon, including edge cases [15].

- Consistency: Data should be in a uniform format with standardized labels to avoid ambiguity [15].

In the context of benchmarking DGE tools, the "ground truth" typically refers to a validated set of genes that are known to be differentially expressed or non-differentially expressed between conditions.

Experimental Reference Data

Experimental, or empirical, reference data are generated through controlled laboratory techniques where the "true" biological signal is established using trusted methods.

The following table summarizes common types of experimental reference data used in genomics.

Table 1: Types of Experimental Reference Data for DGE Benchmarking

| Data Type | Description | Example Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Controls [16] | Synthetic RNA molecules from an external species (e.g., ERCC standards) are added to the sample at known concentrations before library preparation. | 1. Dilute spike-in RNA mixes to create a known concentration gradient. 2. Add a consistent volume to each sample prior to RNA extraction. 3. Proceed with standard RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing. |

| Cell Mixture Experiments [16] | Genetically distinct cell lines are mixed in predefined proportions to create samples with known cellular composition. | 1. Culture different cell lines (e.g., human and mouse). 2. Count cells and mix at specific ratios (e.g., 50:50, 90:10). 3. Extract RNA from the mixture or perform single-cell RNA-seq. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [16] | Cells are sorted into known, biologically defined subpopulations using fluorescent markers prior to sequencing. | 1. Dissociate tissue into a single-cell suspension. 2. Label cells with fluorescent antibodies against known surface markers. 3. Use FACS to isolate pure populations of interest (e.g., T-cells, neurons). 4. Sequence the sorted populations separately. |

| Orthogonal Validation [16] | A subset of genes identified as DE by sequencing is validated using a different technology, such as qPCR. | 1. Perform RNA-seq on samples to get a list of candidate DE genes. 2. Design primers for a subset of these genes. 3. Run quantitative PCR (qPCR) on the same RNA samples. 4. Treat the qPCR results as a high-confidence gold standard for the selected genes. |

Simulated Reference Data

Simulated data are generated in silico using statistical or machine learning models to replicate the properties of real biological data, with a known ground truth programmed into the data from the start.

Simulation Methods and Workflows

Simulation methods for RNA-seq data typically use a two-step process: first, they estimate parameters (e.g., gene mean expression, dispersion, dropout rates) from a real experimental dataset; second, they use these parameters to generate new synthetic count data based on an underlying statistical model [17]. The following diagram illustrates this general workflow and its application in benchmarking.

A wide variety of simulation tools have been developed, each employing different statistical frameworks to model the complexities of gene expression data [17].

Table 2: Common Statistical Models for Simulating RNA-seq Data

| Model Type | Representative Tools | Key Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial (NB) | DESeq, edgeR [18] | Models count data; accounts for overdispersion common in biological replicates. | Benchmarking under realistic biological variability. |

| Zero-Inflated NB (ZINB) | ZINB-WaVE [17] | Adds an extra parameter to model "dropouts" (excess zeros) common in scRNA-seq. | Evaluating performance on sparse single-cell data. |

| Non-Parametric | SAMseq [18] | Makes fewer assumptions about data distribution; uses resampling. | Robust benchmarking when distributional assumptions are uncertain. |

| Deep Learning (VAE) | Generative VAEs [19] | Learns a low-dimensional representation of data to generate realistic samples. | Creating complex, highly realistic datasets from large compendia. |

Comparative Analysis: Simulated vs. Experimental Data

The choice between simulated and experimental reference data involves trade-offs. A comprehensive benchmarking study will often leverage both to obtain the most complete picture of a tool's performance [16].

Table 3: Objective Comparison of Gold Standard Data Types

| Evaluation Criterion | Experimental Reference Data | Simulated Reference Data |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth Certainty | High for validated genes, but can be imperfect or incomplete [20]. | Perfect and complete by design; every gene's status is known [16]. |

| Biological Fidelity | Inherently high; reflects true biological and technical noise [16]. | Varies by method; may not capture all complex properties of real data [17]. |

| Scalability & Cost | Limited and expensive to produce at large scale [16]. | Highly scalable and cost-effective; unlimited data can be generated [16]. |

| Flexibility & Control | Low; difficult to control specific parameters like effect size or sample size. | High; full control over parameters like sample size, effect size, and noise level [16]. |

| Primary Use Case | Final validation and to demonstrate real-world applicability [16]. | Initial method development, extensive power analyses, and stress-testing [17] [16]. |

Key performance insights from benchmark studies include:

- No single simulation method outperforms all others across every evaluation criterion (e.g., data property estimation, biological signal retention, scalability), highlighting the importance of method selection [17].

- Methods that perform well on one task (e.g., capturing data properties) may show trade-offs in computational scalability [17]. For instance, SPsimSeq captures gene-wise correlations well but can be slow for large-scale simulations.

- Benchmarking with very small sample sizes, common in RNA-seq, is problematic for all DGE tools, and results from such conditions should be interpreted cautiously [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources used in generating and working with gold standard data for DGE benchmarking.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for DGE Benchmarking

| Item | Function in Benchmarking | Example Products/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | Provides a set of transcripts at known concentrations added to samples before sequencing to create an internal standard for evaluating sensitivity and accuracy [16]. | Thermo Fisher Scientific ERCC Spike-In Mixes |

| Reference RNA Samples | Commercially available, well-characterized RNA from various tissues or cell lines, used as a consistent baseline across experiments and labs. | Stratagene Universal Human Reference RNA, Microarray Quality Control (MAQC) samples |

| Curated Public Datasets | Experimental datasets with established ground truth, used for community-wide benchmarking and tool comparison. | Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) [21], Sequence Read Archive (SRA), refine.bio [19] |

| Simulation Software | In silico generation of RNA-seq count data with a known ground truth for controlled performance testing. | SPARSim, ZINB-WaVE, SymSim [17]; ART, NEAT for sequencing reads [21] |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | Pre-built pipelines and packages that facilitate the standardized comparison of multiple computational methods. | SimBench [17], muscat [6] |

Both experimental and simulated gold standards are indispensable for the robust benchmarking of differential gene expression tools. Experimental data provides biological verisimilitude, while simulated data offers unparalleled control and scalability. The most rigorous benchmarking strategy is a hybrid one.

Best Practices for Researchers:

- Define the Benchmarking Goal: Clearly state whether you are stress-testing a method under specific conditions (favoring simulation) or validating its real-world readiness (requiring experimental data) [16].

- Use Both Data Types: Use simulated data for initial, extensive testing and power analysis. Validate conclusive findings on a smaller set of high-quality experimental reference data [16].

- Select Appropriate Simulation Tools: Choose a simulator whose strengths (e.g., capturing dropout rates, gene-wise correlations) align with your benchmarking goals, and be aware of its limitations [17].

- Ensure Data Quality and Relevance: For experimental data, prioritize accuracy and completeness through rigorous annotation and validation [15]. For simulated data, always check that the synthetic data captures key properties of the real biological system under study [16].

By thoughtfully integrating both types of gold standard data, researchers can obtain a comprehensive and reliable evaluation of computational tools, thereby accelerating the development of more accurate and robust methods for genomic research and drug development.

The Self-Assessment Trap in Algorithm Development

In the rapidly advancing field of genomic science, the development of new algorithms for differential gene expression (DGE) analysis represents a critical frontier for biological discovery and therapeutic development. However, this progress is threatened by a pervasive "self-assessment trap" – a methodological pitfall wherein developers benchmark their tools using limited datasets, oversimplified experimental conditions, or inappropriate performance metrics that favor their own methods. This trap compromises the real-world utility of analytical tools, potentially leading to false biological conclusions and misallocated research resources.

Substantial evidence indicates this problem is widespread. A 2023 benchmark study evaluating 46 differential expression workflows revealed that technical factors including batch effects, sequencing depth, and data sparsity substantially impact performance, yet these variables are frequently overlooked in method development [3]. Similarly, a 2025 comparison of expression forecasting methods found that "it is uncommon for expression forecasting methods to outperform simple baselines" when subjected to rigorous testing on diverse datasets [8]. These findings underscore how inadequate benchmarking practices can lead to overoptimistic performance claims that fail to materialize in real-world applications.

The stakes for avoiding these pitfalls are exceptionally high. With the global gene expression analysis market projected to reach $7.84 billion by 2030 and researchers increasingly relying on computational predictions to prioritize experimental targets, the consequences of flawed benchmarking extend beyond academic circles to affect drug development pipelines and clinical decision-making [14]. This review examines the current state of benchmarking practices for differential gene expression tools, identifies common shortcomings, and provides experimental frameworks for more rigorous algorithm evaluation.

The Benchmarking Crisis in Computational Biology

Prevalence of the Self-Assessment Trap

Multiple large-scale independent evaluations have revealed significant disparities between developer-reported performance and real-world utility of DGE tools. Several factors contribute to this phenomenon:

- Limited contextual testing: Methods are frequently tested in only a small number of cellular contexts, despite evidence that performance varies substantially across biological systems [8]

- Inadequate data splitting: Many evaluations fail to properly separate training and test data, with some studies allowing the same perturbation conditions to appear in both sets, creating artificially inflated performance metrics [8]

- Overreliance on synthetic data: Benchmarks based primarily on simulated data may not capture the full complexity of real biological systems, leading to tools that perform well in theory but poorly in practice

The 2025 PEREGGRN benchmarking platform study highlighted these issues, noting that "existing empirical results have shortcomings" and that "researcher degrees of freedom" in iterative testing can lead to "overoptimistic results" [8]. This problem is particularly acute for methods claiming to forecast gene expression changes in response to novel genetic perturbations, where proper experimental design is crucial for meaningful validation.

Consequences of Inadequate Benchmarking

The repercussions of insufficient benchmarking extend throughout the research pipeline:

- Irreproducible findings: A 2018 comprehensive evaluation of 25 DGE pipelines found that "about half of the methods showed a substantial excess of false discoveries, making these methods unreliable for DE analysis and jeopardizing reproducible science" [22]

- Reduced translational potential: Tools optimized for performance on idealized datasets frequently fail when applied to complex clinical samples, where factors like cellular heterogeneity, technical noise, and batch effects complicate analysis

- Resource misallocation: Laboratories may invest substantial time and resources implementing tools that appear promising in publications but prove inadequate for their specific research needs

Table 1: Common Benchmarking Deficiencies and Their Impacts

| Benchmarking Deficiency | Frequency | Primary Impact | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited dataset diversity | Common [8] | Reduced generalizability | Testing on only 1-2 cell types |

| Improper train-test splitting | Common [8] | Inflated performance metrics | Same perturbations in training and test sets |

| Inadequate positive controls | Occasional [23] | Uncalibrated error rates | No spike-in RNA controls |

| Overfitting to simulation parameters | Frequent [3] | Poor real-world performance | Tools optimized for specific distribution assumptions |

Methodological Standards for Rigorous Benchmarking

Experimental Design Considerations

Robust benchmarking requires careful experimental design that anticipates the diverse conditions under which tools will be deployed:

- Balanced study designs: For batch effect correction evaluation, implement "balanced" designs where "each batch contained both the sample conditions to be compared" [3]. This approach enables proper separation of technical and biological variability.

- Comprehensive positive controls: Integrate external spike-in RNA controls with known abundance ratios, such as the ERCC control mixtures, which provide "a truth set to benchmark the accuracy of endogenous transcript ratio measurements" [23].

- Appropriate data splitting: For perturbation forecasting benchmarks, ensure that "no perturbation condition is allowed to occur in both the training and the test set" [8]. This validates the method's ability to generalize to truly novel conditions.

Performance Metrics and Evaluation

Selecting appropriate performance metrics is crucial for meaningful benchmarking:

- Multiple metric classes: The PEREGGRN framework categorizes metrics into three classes: (1) standard performance metrics (MAE, MSE, correlation), (2) metrics focused on top differentially expressed genes, and (3) cell type classification accuracy [8].

- Bias-variance tradeoffs: Different metrics emphasize different aspects of performance, with MSE emphasizing large errors and rank-based metrics prioritizing gene ordering [8].

- Precision-oriented measures: For sparse single-cell data, consider F~0.5~-scores and partial AUPR that "weigh precision higher than recall" because "precision has been of particular importance because we often needed to identify a small number of marker genes from sparse and noisy scRNA-seq data" [3].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Benchmarking Workflow. A robust benchmarking framework encompasses three phases: design, implementation, and evaluation, with specific considerations at each stage.

Comparative Analysis of Differential Expression Methods

Performance Across Experimental Conditions

Large-scale benchmarking studies have revealed that method performance varies significantly across different experimental conditions:

- Sequencing depth impact: As depth decreases, "the relative performances of Wilcoxon test and FEM for log-normalized data were distinctly enhanced for low depths, whereas scVI improved limmatrend no more" [3].

- Batch effect sensitivity: For large batch effects, "covariate modeling overall improved DE analysis," but "its benefit was diminished for very low depths" [3].

- Data type considerations: Methods optimized for mRNA data often "exhibit inferior performance for lncRNAs compared to mRNAs across all simulated scenarios and benchmark RNA-seq datasets" [22].

Table 2: Differential Expression Tool Performance Across Conditions

| Tool Category | High Sequencing Depth | Low Sequencing Depth | Large Batch Effects | Single-Cell Data | lncRNA Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| limma/limma-trend | Excellent [3] | Good [3] | Good with covariates [3] | Variable [3] | Good [22] |

| DESeq2 | Excellent [3] [24] | Good [3] | Good with covariates [3] | Moderate [3] | Moderate [22] |

| edgeR | Excellent [24] | Good [3] | Good with covariates [3] | Good with ZINB-WaVE [3] | Moderate [22] |

| Wilcoxon Test | Moderate [3] | Excellent [3] | Poor [3] | Good [3] | Not recommended [22] |

| MAST | Good [3] | Good [3] | Excellent with covariates [3] | Excellent [3] | Not evaluated |

| SAMSeq | Good [22] | Good [22] | Moderate [22] | Not evaluated | Best in class [22] |

Emerging Methods and Performance Claims

Recent methodological advances promise improved performance but require rigorous independent validation:

- DiSC: A novel method for individual-level differential expression analysis in single-cell data that claims to be "approximately 100 times faster than other state-of-the-art methods" while maintaining competitive false discovery rate control [25].

- IDEAS and BSDE: Approaches that "analyze the full distributional characteristics of gene expression using distance metrics, but they are computationally intensive and may not scale well to large datasets" [25].

- Covariate modeling: Approaches that incorporate batch information as covariates in statistical models generally outperform methods that rely on pre-corrected data, particularly for large batch effects [3].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Framework

Based on recent large-scale evaluations, the following protocol provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking differential expression tools:

Dataset Curation

- Select diverse datasets encompassing multiple biological contexts, perturbation types, and sequencing technologies

- Include datasets with external spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA controls) to establish ground truth [23]

- For single-cell methods, incorporate data with varying levels of sparsity and cellular heterogeneity

Experimental Conditions

- Test performance across a range of sequencing depths (e.g., depth-4, depth-10, depth-77) to assess robustness [3]

- Evaluate sensitivity to batch effects by intentionally introducing technical covariates or utilizing naturally batch-structured data

- Assess performance across different levels of biological effect sizes and proportions of truly differentially expressed genes

Comparison Framework

- Implement multiple competing methods using consistent preprocessing and normalization approaches

- Utilize standardized metric calculations to ensure fair comparisons

- Perform statistical testing to determine whether performance differences are significant rather than relying on point estimates alone

Specialized Benchmarking Scenarios

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Benchmarking

The growth of single-cell technologies necessitates specialized benchmarking approaches:

- Individual-level analysis: With scRNA-seq studies now including multiple individuals, novel approaches like DiSC address "individual-to-individual variability, upon cell-to-cell variability within the same individual" [25].

- Pseudobulk approaches: These methods "showed good pAUPRs for small batch effects; however, they performed the worst for large batch effects" [3].

- Covariate adjustment: For large batch effects in single-cell data, "covariate modeling overall improved DE analysis" for methods like MAST and ZINB-WaVE weighted edgeR [3].

Long-Read RNA-Seq Benchmarking

Emerencing long-read technologies present unique benchmarking challenges:

- Isoform-level analysis: Benchmarking studies have identified StringTie2 and bambu as top-performing for isoform detection, while "DESeq2, edgeR and limma-voom were best amongst the 5 differential transcript expression tools tested" [24].

- Spike-in controls: Studies utilizing synthetic spike-in RNAs ("sequins") provide ground truth for evaluating isoform-level quantification accuracy [24].

Diagram 2: Multi-Dimensional Evaluation Framework. Comprehensive benchmarking assesses technical performance, computational efficiency, and biological relevance to provide a complete picture of method utility.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of differential expression analysis depends on both computational methods and experimental reagents. The following table outlines critical resources for robust benchmarking studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Differential Expression Benchmarking

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Key Features | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | External RNA controls with defined abundance ratios [23] | 92 RNA transcripts with known ratios across mixtures; provides ground truth for differential expression | Technical performance assessment; limit of detection calculation; interlaboratory comparisons |

| Sequins (Synthetic Spike-Ins) | Artificial RNA sequences spiked into samples [24] | Designed to mimic natural transcripts; enables isoform-level benchmarking | Long-read RNA-seq method evaluation; differential transcript usage analysis |

| Reference RNA Materials | Standardized RNA samples from specific tissues [23] | Well-characterized composition; enables cross-platform and cross-laboratory comparisons | Method reproducibility assessment; platform performance evaluation |

| 10x Genomics Platforms | Single-cell RNA sequencing solutions [14] | High-throughput single-cell profiling; reveals cellular heterogeneity | Single-cell method benchmarking; cellular heterogeneity studies |

| Validated Positive Control Genes | Genes with established expression patterns | Known differential expression across conditions; biological ground truth | Biological validation of computational predictions |

Escaping the self-assessment trap in algorithm development requires a fundamental shift in how we evaluate computational methods for differential gene expression analysis. The evidence from recent large-scale benchmarking studies consistently demonstrates that methodological performance is highly context-dependent, with factors such as sequencing depth, data sparsity, batch effects, and biological system significantly influencing results.

To foster development of more robust and reliable tools, the field should embrace:

- Standardized benchmarking platforms like PEREGGRN that enable "neutral evaluation across varied methods, parameters, datasets, and evaluation schemes" [8]

- Transparent reporting of limitations and failure modes alongside performance claims

- Community-wide adoption of rigorous benchmarking practices that prioritize real-world utility over optimized performance on idealized datasets

By implementing the comprehensive benchmarking frameworks and experimental protocols outlined in this review, researchers can avoid the self-assessment trap and develop computational tools that genuinely advance biological discovery and therapeutic development.

In the analysis of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data, accurately modeling count distributions represents a fundamental statistical challenge with direct implications for differential expression (DE) analysis. The digital nature of RNA-seq data, where expression is quantified as the number of reads mapping to a gene, requires specialized statistical approaches that account for its unique characteristics. Two dominant families of distributions have emerged: the Negative Binomial (NB) distribution, which has become the standard for bulk RNA-seq analysis, and various Zero-Inflated models, which have been increasingly applied to single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data to handle excess zeros. The choice between these distributions profoundly impacts the identification of differentially expressed genes, potentially leading to different biological interpretations.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these key statistical distributions within the context of benchmarking differential gene expression tools. We examine their theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and performance characteristics based on experimental data, providing researchers with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate methodologies.

Core Statistical Distributions for RNA-seq Data

Negative Binomial Distribution

The Negative Binomial distribution has become the cornerstone model for bulk RNA-seq data analysis, implemented in widely used tools such as DESeq2 and edgeR. Its fundamental equation is defined as follows for a random variable Y (read count) with mean μ and dispersion φ:

$$ P(Y=y) = \frac{\Gamma(y + \frac{1}{\phi})}{\Gamma(y+1)\Gamma(\frac{1}{\phi})} \left(\frac{1}{1+\mu\phi}\right)^{\frac{1}{\phi}} \left(\frac{\mu}{\frac{1}{\phi}+\mu}\right)^y $$

The critical advantage of the NB distribution lies in its ability to model overdispersion—a phenomenon where the variance of the data exceeds the mean, which is consistently observed in RNA-seq data [26] [27]. The dispersion parameter φ quantifies this extra-Poisson variation, with larger values indicating greater overdispersion. In practice, the NB model accounts for both technical variance (from sequencing) and biological variance (from true biological differences between replicates) [27].

Proper dispersion estimation is crucial for reliable DE detection. Underestimation of dispersion may lead to false discoveries, while overestimation reduces statistical power to detect truly differentially expressed genes [26]. Methods such as those implemented in DESeq2 and edgeR use Bayesian shrinkage approaches to stabilize dispersion estimates by borrowing information across genes, significantly improving the stability and reliability of DE testing [26] [28].

Zero-Inflated Models

Zero-Inflated models address a key characteristic of scRNA-seq data: the excess of zero counts beyond what standard count distributions predict. These models combine two components: a point mass at zero (representing excess zeros) and a standard count distribution (Poisson or Negative Binomial). The fundamental equation for a Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) distribution is:

$$ f{ZINB}(y{ij};\mu{ij},\thetaj,\pi{ij}) = \pi{ij}\delta0(y{ij}) + (1-\pi{ij})f{NB}(y{ij};\mu{ij},\theta_j) $$

Where:

- $π{ij}$ is the probability that a count $y{ij}$ is an excess zero

- $δ_0$ is the Dirac delta function (point mass at zero)

- $f_{NB}$ is the standard Negative Binomial probability mass function

- $μ_{ij}$ is the mean parameter

- $θ_j$ is the dispersion parameter [29]

These models conceptualize two types of zeros: biological zeros (true absence of gene expression) and technical zeros (also called "dropout" events, where technical limitations prevent detection of truly expressed genes) [30]. The controversy in the field centers on whether zeros in scRNA-seq data should be primarily treated as biological signals or as missing data to be corrected [30].

Table 1: Types of Zeros in scRNA-seq Data

| Type | Description | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Zeros | True absence of gene transcripts in a cell | Unexpressed genes or transcriptional bursting |

| Technical Zeros | Failure to detect truly expressed transcripts | Imperfect mRNA capture efficiency during reverse transcription |

| Sampling Zeros | Undetected expression due to limited sequencing depth | Limited sequencing depth or inefficient cDNA amplification [30] |

Two main frameworks implement zero-inflation modeling:

- Zero-Inflated Models: Proper two-component mixture models that can only increase the probability of P(Y=0) [31]

- Hurdle Models: Two-part models that first model the probability of a zero versus non-zero, then model the non-zero values using a zero-truncated distribution [31]

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Benchmarking Methodologies

Robust benchmarking of statistical methods requires carefully designed simulation studies that reflect real data characteristics. The following experimental approaches have been employed in comparative studies:

Simulation Based on Real Data Characteristics: One approach involves simulating datasets from the negative binomial model using fundamental information from real datasets while preserving observed relationships between dispersions and gene-specific mean counts [26]. This maintains biological realism while allowing controlled performance comparisons.

Real Data-Based Semiparametric Simulation: For correlated microbiome data (which shares characteristics with scRNA-seq), researchers have developed a semiparametric framework that draws random samples from a large reference dataset (non-parametric component) and adds covariate effects parametrically [32]. This approach circumvents difficulties in modeling complex inter-subject variation while maintaining realistic data structures.

Weighting Strategy Evaluation: To evaluate zero-inflation handling, researchers have implemented a weighting approach based on ZINB-WaVE, which identifies excess zero counts and generates gene- and cell-specific weights. These weights are then incorporated into bulk RNA-seq DE pipelines (edgeR, DESeq2, limma-voom) to evaluate performance improvements with zero-inflated data [29].

The performance metrics typically used in these benchmarks include:

- False discovery rate (FDR) control

- Statistical power to detect true differential expression

- Accuracy and precision of parameter estimation

- Mean squared error (MSE) for parameter estimates

- Computational efficiency

Performance Comparison Results

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Statistical Distributions for RNA-seq Data

| Distribution | Best For | Strengths | Limitations | Key Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial | Bulk RNA-seq data | Handles overdispersion effectively; Established statistical framework | May overestimate dispersion with excess zeros, reducing power | DESeq2, edgeR |

| Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial | scRNA-seq data with excess zeros | Explicitly models excess zeros; More biologically realistic for sparse data | Increased model complexity; Computational intensity | ZINB-WaVE + edgeR/DESeq2 |

| Zero-Inflated Poisson | Count data with overdispersion and zero inflation | Simpler than ZINB; Good for moderate overdispersion | Cannot handle severe overdispersion alone | PScl package, gamlss |

| Hurdle Models | Zero-inflated count data | Flexible two-part modeling; Interpretable components | May have reduced efficiency if zeros are not structural | pcsl, mhurdle |

Studies evaluating DE analysis in scRNA-seq data have revealed that traditional bulk RNA-seq tools (based on NB models) can be successfully applied to single-cell data when appropriately weighted to handle zero inflation [29]. In fact, combinations like edgeR-zinbwave and DESeq2-zinbwave have demonstrated competitive performance compared to methods specifically designed for scRNA-seq data [33].

For bulk RNA-seq data, methods employing a moderate degree of dispersion shrinkage—such as DSS, Tagwise wqCML, and Tagwise APL—have shown optimal test performance when combined with the QLShrink test in the QuasiSeq R package [26]. Linear model-based methods like LinDA, MaAsLin2, and LDM have demonstrated greater robustness than generalized linear model-based methods in correlated microbiome data, with LinDA specifically maintaining reasonable performance in the presence of strong compositional effects [32].

Decision Framework and Research Toolkit

Distribution Selection Guide

The relationship between data characteristics and appropriate statistical models can be visualized as follows:

This decision framework emphasizes that data type (bulk vs. single-cell) and specific characteristics (overdispersion, zero percentage) should drive distribution selection rather than methodological trends.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RNA-seq Distribution Analysis

| Tool/Package | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial-based DE analysis | R/Bioconductor |

| edgeR | Negative Binomial and quasi-likelihood methods | R/Bioconductor |

| ZINB-WaVE | Zero-inflated negative binomial model with weights | R/Bioconductor |

| limma-voom | Linear modeling of log-counts with precision weights | R/Bioconductor |

| MAST | Hurdle model for scRNA-seq data | R/Bioconductor |

| scMMST | Mixed model score tests for zero-inflated scRNA-seq data | R/Bioconductor |

| NBAMSeq | Negative binomial additive models for nonlinear effects | R/Bioconductor |

Advanced Modeling Considerations

Addressing Nonlinear Relationships

While standard NB and ZINB models assume linear covariate effects, real RNA-seq data often exhibits nonlinear relationships between covariates and gene expression. For example, in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) data, 30 out of 250 age-associated genes showed significant nonlinear patterns that would be missed by standard linear models [28]. The NBAMSeq package addresses this through generalized additive models (GAMs) based on the negative binomial distribution, allowing for smooth nonlinear effects while maintaining the advantages of information sharing across genes for dispersion estimation [28].

Handling Multicollinearity in Zero-Inflated Models

In zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINBR) models, high correlations between predictor variables (multicollinearity) can compromise the stability and reliability of parameter estimates. New two-parameter hybrid estimators have been developed to address this problem, combining existing biased estimators (Ridge and Liu, Kibria-Lukman, modified Ridge) to mitigate multicollinearity effects [34]. Simulation studies show these hybrid estimators consistently outperform conventional methods, especially under high multicollinearity conditions, producing more stable and accurate parameter estimates [34].

The selection between Negative Binomial and Zero-Inflated distributions for RNA-seq data analysis should be guided by data characteristics rather than methodological preference. For bulk RNA-seq data, where overdispersion is the primary concern, the Negative Binomial distribution remains the gold standard, with shrinkage-based dispersion estimation providing optimal performance. For scRNA-seq data, where zero inflation presents additional challenges, Zero-Inflated models or weighted approaches that augment traditional NB methods generally provide superior performance.

Future methodological development will likely focus on integrating these approaches with emerging computational challenges, including large-scale datasets, complex experimental designs, and multi-omics integration. As the field progresses, continuous benchmarking using standardized frameworks will remain essential for validating new methodological claims and providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for biological discovery.

DGE Tool Categories and Their Applications Across Transcriptomic Data Types

Differential expression (DE) analysis of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data is a fundamental step in understanding how genes respond to different biological conditions, from disease states to experimental treatments. The field has converged on three principal tools as statistical workhorses: edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom. Each provides a distinct approach to handling the count-based, over-dispersed nature of RNA-seq data while accounting for biological variability and technical noise. Understanding their unique statistical foundations, performance characteristics, and optimal applications is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on accurate transcriptome analysis for discovery and validation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these tools based on current benchmarking evidence, detailing their fundamental methodologies and empirical performance across various experimental conditions.

Statistical Foundations and Core Methodologies

The three tools employ different but related statistical strategies to identify differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq count data. The table below summarizes their core approaches, normalization methods, and variance handling techniques.

Table 1: Statistical Foundations of edgeR, DESeq2, and limma

| Aspect | limma | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation |

| Data Transformation | voom transformation converts counts to log-CPM values |

Internal normalization based on geometric mean | TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) normalization by default |

| Variance Handling | Empirical Bayes moderation improves variance estimates for small sample sizes | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes | Flexible options for common, trended, or tagged dispersion |

| Key Components | • voom transformation• Linear modeling• Empirical Bayes moderation• Precision weights |

• Normalization• Dispersion estimation• GLM fitting• Hypothesis testing | • Normalization• Dispersion modeling• GLM/QLF testing• Exact testing option |

limma-voom Framework

Originally developed for microarray data, limma (Linear Models for Microarray Data) employs linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation to analyze gene expression experiments. For RNA-seq data, the voom (variance modeling at the observational level) function transforms count data into continuous values suitable for linear modeling. The voom function converts counts to log-CPM (counts per million) values and estimates precision weights based on the mean-variance relationship, which are then incorporated into the linear modeling process. This approach allows limma to leverage its powerful empirical Bayes methods that borrow information across genes to stabilize variance estimates, particularly beneficial for studies with small sample sizes [35] [36].

DESeq2 Approach

DESeq2 utilizes a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) with empirical Bayes shrinkage for dispersion estimation and fold change stabilization. Its core normalization method, RLE (Relative Log Expression), calculates size factors by comparing each sample to a geometric mean reference sample. DESeq2 implements sophisticated shrinkage estimators for both dispersion parameters and log2 fold changes, which improve stability and reproducibility, especially for genes with low counts or small sample sizes. The package also includes automatic outlier detection and independent filtering to increase detection power [35] [37].

edgeR Methodology

edgeR also employs negative binomial models but offers more flexible dispersion estimation options. Its default TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) normalization effectively handles composition biases between samples. edgeR provides multiple testing frameworks, including likelihood ratio tests for GLMs, exact tests for simple designs, and quasi-likelihood F-tests that account for uncertainty in dispersion estimation. This flexibility allows users to tailor the analysis approach to their specific experimental design and data characteristics [35] [37].

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Evidence

Multiple independent studies have evaluated the performance of these tools across various experimental conditions. The table below summarizes their relative strengths and optimal use cases.

Table 2: Performance Comparison and Ideal Use Cases

| Aspect | limma | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates per condition | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples |

| Best Use Cases | • Small sample sizes• Multi-factor experiments• Time-series data• Integration with other omics | • Moderate to large sample sizes• High biological variability• Subtle expression changes• Strong FDR control | • Very small sample sizes• Large datasets• Technical replicates• Flexible modeling needs |

| Computational Efficiency | Very efficient, scales well | Can be computationally intensive | Highly efficient, fast processing |

| Limitations | • May not handle extreme overdispersion well• Requires careful QC of voom transformation | • Computationally intensive for large datasets• Conservative fold change estimates | • Requires careful parameter tuning• Common dispersion may miss gene-specific patterns |

Real-World Benchmarking Studies

A 2024 multi-center benchmarking study using Quartet and MAQC reference materials across 45 laboratories provided significant insights into real-world RNA-seq performance. This extensive analysis found that despite different methodological approaches, the tools generally show substantial agreement in identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs), particularly for experiments with larger biological differences. However, the study revealed greater inter-laboratory variations in detecting subtle differential expression (minor expression differences between sample groups with similar transcriptome profiles), which is particularly relevant for clinical diagnostics where differences between disease subtypes or stages may be minimal [9].

When examining false discovery rate (FDR) control and sensitivity, analyses of the Bottomly et al. mouse RNA-seq dataset showed that all methods generally maintain FDR close to target levels. However, in 3 vs 3 sample comparisons, DESeq2 and edgeR detected approximately 700 significant genes compared to about 400 for limma-voom, suggesting potentially higher sensitivity for the negative binomial-based methods in very small sample sizes [37].

Robustness and Concordance

A rigorous appraisal of robustness to sequencing alterations using fixed count matrices from breast cancer data found that performance patterns were largely dataset-agnostic when sample sizes were sufficiently large. The study reported the following robustness ranking: NOISeq > edgeR > voom > EBSeq > DESeq2, though all methods showed reasonable performance [38].

Across multiple benchmarks, DESeq2 and edgeR typically show about 80-90% overlap in their significant gene calls, with each method capturing a small subset of unique genes. These unique calls often represent biologically relevant findings rather than false positives, indicating complementary strengths [37].

Practical Implementation and Workflow

Data Preparation and Quality Control

Proper data preprocessing is essential for reliable differential expression analysis. The initial steps include:

- Quality Control and Trimming: Tools like fastp or Trim Galore (which integrates Cutadapt and FastQC) remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases. Studies show fastp significantly enhances processed data quality and improves subsequent alignment rates [39].

- Read Alignment and Quantification: Sequences are aligned to a reference genome/transcriptome using specialized aligners, followed by generation of count matrices.

- Filtering Low-Expressed Genes: Remove uninformative genes with minimal expression. A common approach is keeping genes expressed (CPM > 1) in at least 80% of samples [35] [40].

Figure 1: RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

Normalization Methods Comparison

Normalization addresses technical variations in sequencing depth and RNA composition. The principal methods include:

Table 3: Comparison of Normalization Methods

| Method | Package | Approach | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | edgeR | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Robust to differentially expressed genes; less correlated with library size |

| RLE | DESeq2 | Relative Log Expression | Based on geometric mean; comparable to MRN |

| MRN | - | Median Ratio Normalization | Similar to RLE; performs slightly better in some simulations |

Studies indicate that while these methods differ mathematically, they produce similar results in practice, particularly for simple experimental designs. For complex designs, the choice of normalization method becomes more critical [41] [42].

Differential Analysis Code Framework

Each tool has a distinct implementation workflow in R:

DESeq2 Pipeline:

edgeR Pipeline:

limma-voom Pipeline:

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Reference Material Design

Robust benchmarking requires appropriate reference materials with known expression differences:

- MAQC Reference Samples: Derived from cancer cell lines (MAQC A) and human brain tissue (MAQC B) with large biological differences [9].

- Quartet Reference Materials: Derived from B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family with subtle biological differences, better mimicking clinical scenarios where expression differences between conditions may be minimal [9].

- ERCC Spike-In Controls: Synthetic RNA controls with known concentrations spiked into samples provide built-in truth for absolute expression assessment [9].

Performance Assessment Metrics

Comprehensive benchmarking utilizes multiple complementary metrics:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Based on principal component analysis to quantify separation between biological signals versus technical noise [9].

- Accuracy of Expression Measurements: Correlation with ground truth data from TaqMan assays or known spike-in concentrations [9].

- False Discovery Rate Assessment: Comparison of positive calls in small subsets versus larger reference sets to estimate FDR [37].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Proportion of true positives detected from a reference set of differentially expressed genes [37].

Figure 2: Benchmarking Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Provide ground truth for method validation | Quartet project samples, MAQC samples, ERCC spike-in controls |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess raw read quality and adapter contamination | FastQC, MultiQC, fastp, Trim Galore |

| Alignment Software | Map sequencing reads to reference genome | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 |

| Quantification Tools | Generate count matrices from aligned reads | featureCounts, HTSeq-count, Salmon |

| Differential Expression Packages | Identify statistically significant expression changes | edgeR, DESeq2, limma-voom |

| Visualization Tools | Explore and present results | ggplot2, EnhancedVolcano, pheatmap |