A Standardized CRISPR Screening Workflow: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for standardizing CRISPR screening workflows, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Standardized CRISPR Screening Workflow: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for standardizing CRISPR screening workflows, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of CRISPR technology, explores advanced methodological applications and single-cell integration, details robust troubleshooting and optimization strategies for enhanced efficiency and specificity, and establishes a framework for the analytical validation and comparative analysis of screening data. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to enhance the reproducibility, reliability, and translational impact of CRISPR screens in biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and System Selection for CRISPR Screening

Core Concepts: From Bacterial Immunity to Gene Editing

What is the CRISPR-Cas9 system and how did it originate?

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and their associated protein (Cas-9) system originated as an adaptive immune mechanism in prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) to defend against viruses or bacteriophages [1]. The system allows these organisms to "remember" past infections by integrating short fragments of viral DNA (spacers) into their own genomes at a specific locus called the CRISPR array [1]. Upon re-infection, this genetic memory is used to recognize and cleave the foreign DNA, neutralizing the threat [2]. This natural defense mechanism was later repurposed by scientists into a highly versatile and programmable genome-editing tool [1] [2].

What are the key components of the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery?

The engineered CRISPR-Cas9 system for genome editing consists of two essential components [1] [3]:

- Cas9 Nuclease: Often called "molecular scissors," this protein is responsible for cutting the double-stranded DNA at a specific location. The most commonly used version comes from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) [1] [3].

- Guide RNA (gRNA): This is a synthetic RNA molecule that combines two natural RNAs: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which specifies the target DNA sequence through complementary base-pairing, and the trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 protein [1] [3]. The gRNA directs the Cas9 protein to the precise site in the genome that needs to be edited.

How does the CRISPR-Cas9 system achieve targeted DNA cleavage?

The mechanism can be broken down into three main steps: recognition, cleavage, and repair [1].

- Recognition: The gRNA directs the Cas9 protein to a target DNA sequence that is complementary to the 5' end of the gRNA. However, Cas9 will only bind to a target site if it is immediately followed by a short DNA sequence known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [3] [2]. For the common SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' (where "N" is any nucleotide) [1] [3].

- Cleavage: Once the Cas9-gRNA complex binds to the target DNA with the correct PAM, the Cas9 protein undergoes a conformational change that activates its two nuclease domains: the HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, and the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary strand [1] [4]. This results in a precise Double-Strand Break (DSB) in the DNA [1].

- Repair: The cell's innate DNA repair machinery then attempts to fix the break. There are two primary pathways [1] [2]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is an error-prone process that directly ligates the broken ends together, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt the gene's function, effectively creating a knockout [1] [5].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This is a more precise pathway that uses a donor DNA template to repair the break. Researchers can supply a custom donor template to introduce specific genetic changes, such as inserting a new gene or correcting a mutation, achieving a knock-in [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates this core mechanism and the resulting repair pathways:

Troubleshooting Common CRISPR Workflow Challenges

A standardized CRISPR workflow can encounter several technical hurdles. The table below outlines common issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Root Cause | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency [6] | Poor gRNA design, inefficient delivery, or low expression of components. | Verify gRNA targets a unique genomic site. Optimize delivery method (electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) for your specific cell type. Use robust promoters and confirm component quality. [6] |

| High Off-Target Effects [6] [5] | gRNA binding to sequences with high similarity to the target. | Design highly specific gRNAs using prediction tools. Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1). Employ paired nickase systems to double specificity requirements. [6] [5] |

| Cell Toxicity [6] | High concentrations of CRISPR components or prolonged Cas9 expression. | Titrate component concentrations to find balance between editing and viability. Use Cas9 protein or mRNA instead of plasmids for transient expression. Include a nuclear localization signal (NLS). [6] |

| Mosaicism [6] | Editing occurs after DNA replication in a subset of cells within a population. | Optimize timing of component delivery relative to cell cycle. Use inducible Cas9 systems. Isolate fully edited clonal cell lines via single-cell cloning. [6] |

| Inability to Detect Edits | Low sensitivity of genotyping method or inefficient editing. | Use robust detection methods: T7 Endonuclease I assay, Surveyor assay, or sequencing. Ensure your method is sensitive enough for the expected mutation rate. [6] |

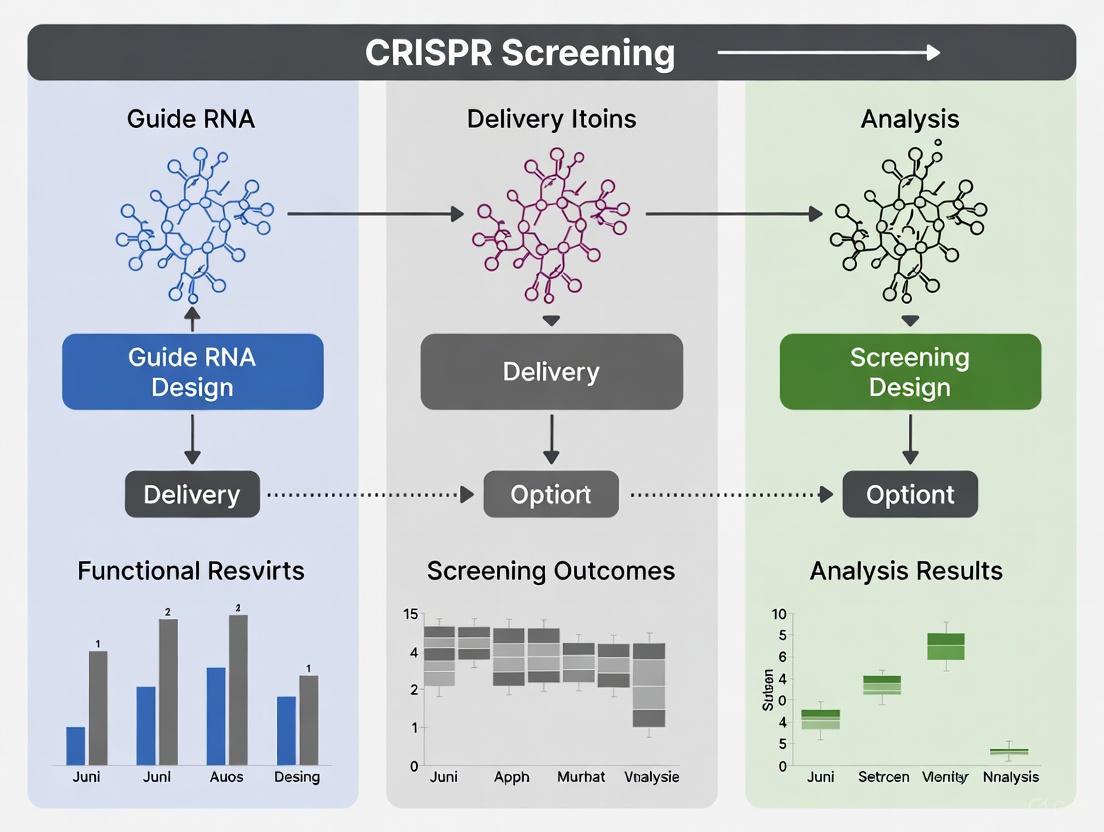

The following workflow diagram integrates these troubleshooting steps into a standardized experimental pipeline:

Advanced Applications & Clinical Translation

How is CRISPR being applied in clinical trials and therapy development?

CRISPR technology has rapidly moved from the lab to the clinic, with the first CRISPR-based medicine, Casgevy, approved for treating sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT) [7]. Clinical applications generally follow two strategies:

- Ex Vivo Editing: Cells (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells for SCD) are extracted from a patient, edited in the lab using CRISPR, and then infused back into the patient [8].

- In Vivo Editing: The CRISPR components are delivered directly into the patient's body to edit cells in situ [8]. A landmark case in 2025 involved a personalized in vivo therapy for an infant with a rare genetic liver disease (CPS1 deficiency), developed and delivered in just six months using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [7].

A major focus of current clinical research is on delivery. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have proven highly successful for targeting the liver, enabling treatments for diseases like hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and hereditary angioedema (HAE) [7]. LNPs also offer the potential for re-dosing, as they do not trigger the same immune responses as viral vectors [7].

What are the key regulatory and manufacturing challenges for clinical CRISPR therapies?

Translating CRISPR into approved therapies faces several hurdles [8] [9]:

- Regulatory Pathways: The existing FDA framework was designed for small-molecule drugs, not complex, living therapies. Navigating the requirements for Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) and determining when to use Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-grade materials can be challenging [8] [9].

- GMP Reagents: Therapies for human trials require GMP-grade Cas nucleases and gRNAs to ensure purity, safety, and efficacy. The supply of true GMP reagents is complex and demand is high [8].

- Manufacturing Consistency: Maintaining consistency in the manufacturing process from research to commercial scale is critical for patient safety and regulatory approval. Changing vendors can introduce variability and invalidate clinical data [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

| Item | Function & Role in Standardization |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) [6] [3] | Engineered versions of the Cas9 nuclease with reduced off-target effects, crucial for improving the specificity and safety of edits. |

| GMP-Grade gRNA & Cas Nuclease [8] | Manufactured under strict Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations. These are mandatory for clinical trials to ensure product purity, safety, and consistency. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [7] [5] | A non-viral delivery vehicle particularly efficient for in vivo delivery to the liver. LNPs are biocompatible and allow for potential re-dosing. |

| Viral Vectors (AAV, Lentivirus) [5] | Commonly used for efficient delivery of CRISPR components. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are often used for in vivo therapy, while lentiviruses are common for ex vivo cell engineering. |

| Donor DNA Template | A synthetic DNA molecule that serves as the repair blueprint for the Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway, enabling precise gene knock-in or correction. [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the biggest delivery challenges for in vivo CRISPR therapies?

The three biggest challenges are often cited as "delivery, delivery, and delivery" [7]. Key hurdles include ensuring the CRISPR components reach the correct cells and avoid off-target tissues, overcoming the limited packaging capacity of efficient viral vectors like AAV, and managing potential immune responses against the delivery vehicle or the bacterial-derived Cas9 protein itself [7] [5].

How can I improve the specificity of my gRNA and reduce off-target effects?

- Bioinformatic Design: Use established online tools and algorithms to design gRNAs and predict potential off-target sites before you begin your experiment. These tools can score gRNAs for predicted efficacy and specificity [6] [10].

- High-Fidelity Cas9: Replace the standard Cas9 with engineered high-fidelity variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) that have reduced off-target activity while maintaining on-target efficiency [6].

- Alternative Systems: Consider using Cas9 nickases, which require two gRNAs to bind in close proximity to create a single DSB, dramatically increasing specificity [2].

What are the key regulatory milestones for taking a CRISPR therapy to clinical trials?

The path from the lab to clinical trials is rigorous [9]:

- Pre-clinical Research: Proof-of-concept studies in cells and animal models to demonstrate efficacy and initial safety.

- INTERACT Meeting: An informal meeting with the FDA for early advice on CMC, toxicology, and clinical plans.

- Pre-IND Meeting: A formal meeting with the FDA to discuss if the pre-clinical data package is sufficient to support a clinical trial application.

- IND Application: Submission of an Investigational New Drug application to the FDA. Approval allows clinical trials to begin.

- Clinical Trial Phases: Progression through Phase I (safety/dosage), Phase II (efficacy/side effects), and Phase III (large-scale efficacy monitoring) trials [9].

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology has evolved beyond simple gene knockout, creating a versatile toolkit for precise genetic manipulation. For researchers aiming to standardize screening workflows, understanding the distinct applications and operational mechanisms of CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko), CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) is fundamental. These systems enable a range of functional genomic studies, from complete gene loss-of-function to tunable gene repression and activation.

Each tool functions through a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs a CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein to a specific DNA sequence [11] [12]. The choice of Cas protein and its functional state (active or deactivated) determines the outcome. This guide provides a comparative overview, detailed methodologies, and troubleshooting support to help you select and implement the optimal CRISPR system for your research goals, contributing to more standardized and reproducible screening outcomes.

CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko)

- Mechanism: CRISPRko utilizes an active nuclease, most commonly Cas9, to create a double-strand break (DSB) in the target gene's DNA [12]. The cell's primary repair mechanism, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the coding sequence, leading to a permanent and complete loss of gene function [13] [14].

- Best For: Essential gene identification, functional gene screening, and generating stable gene knockouts [15].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi)

- Mechanism: CRISPRi employs a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) that binds to DNA without cutting it [15]. When targeted to a gene's promoter region, dCas9 acts as a physical barrier to transcription. This effect is often enhanced by fusing dCas9 to transcriptional repressor domains (e.g., KRAB), resulting in robust and reversible gene silencing without altering the underlying DNA sequence [16] [15].

- Best For: Studying essential genes where knockout is lethal, analyzing reversible gene function, and modeling partial loss-of-function phenotypes.

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa)

- Mechanism: Like CRISPRi, CRISPRa uses dCas9, but it is fused to potent transcriptional activator domains (e.g., VP64, p65) [15]. By targeting these dCas9-activator complexes to gene promoter regions, researchers can specifically upregulate gene expression, enabling gain-of-function studies [16].

- Best For: Gene overexpression studies, genetic rescue experiments, and identifying genes that confer specific phenotypes or drug resistance when activated.

Direct Comparison of CRISPR Modalities

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa to guide your selection.

| Feature | CRISPRko (Knockout) | CRISPRi (Interference) | CRISPRa (Activation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Protein Used | Active Cas9 (or other nucleases like Cas12a) [12] | dCas9 (catalytically dead) [15] | dCas9 (catalytically dead) [15] |

| Molecular Mechanism | Creates double-strand breaks, repaired by error-prone NHEJ [13] [12] | Blocks RNA polymerase binding and recruitment of repressors [15] | Recruits transcriptional activators to the promoter [15] |

| Effect on Gene | Permanent gene disruption | Reversible gene knockdown | Targeted gene upregulation |

| Reversibility | No (Permanent) | Yes (Reversible) | Yes (Reversible) |

| Key Applications | Gene essentiality screens, functional knockout studies [15] | Silencing essential genes, tunable repression studies [15] | Gain-of-function screens, gene activation studies [15] |

| Primary Repair Pathway | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) [12] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

Diagram 1: A workflow to guide the selection of the appropriate CRISPR tool based on the experimental goal.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A standardized CRISPR screening workflow involves multiple critical steps, from initial design to final validation. The following diagram and detailed protocol outline this process.

Diagram 2: The four key phases of a standardized CRISPR gene editing workflow.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Experiment Design and gRNA Selection

- CRISPR System and Cas Enzyme Selection: Choose your system (ko, i, a) based on the comparison in Section 2. For CRISPRko, the most common nuclease is Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), which requires a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site [12]. Consider high-fidelity Cas9 variants to minimize off-target effects [6].

- gRNA Design: Design gRNAs to target the early exons of a gene for CRISPRko to maximize the chance of a disruptive frameshift. For CRISPRi and CRISPRa, gRNAs should be designed to target the promoter region or transcriptional start site (TSS) for optimal efficiency [16].

- Utilize Bioinformatics Tools: Use specialized tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP, CRISPResso) to design highly specific gRNAs and predict potential off-target sites [11]. Proprietary algorithms from commercial providers can also assess on-target efficiency [12].

- gRNA Format: Use a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) format, which combines crRNA and tracrRNA, for simplified design and delivery [12]. Consider chemical modifications (e.g., Alt-R modification) to enhance stability and reduce immune responses [12].

Step 2: Delivery of CRISPR Components

- Formulate Components: For highest efficiency and lowest off-target effects, pre-complex purified Cas9 protein (or dCas9 fusion proteins) with sgRNA to form a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for delivery [12].

- Choose Delivery Method: The optimal method depends on your cell type.

- Electroporation: Highly efficient for a wide range of cell types, including hard-to-transfect cells. Ideal for RNP delivery [12].

- Lipofection: A simpler, lipid-based method suitable for adherent cells that are easy to transfect [12].

- Lentiviral Transduction: Essential for pooled CRISPR screens as it allows for stable genomic integration and long-term expression. Ensure biosafety protocols are followed.

Step 3: Induction of Edits and Cellular Repair

- CRISPRko: After successful RNP delivery and Cas9-mediated DSB formation, the cell's innate NHEJ repair pathway is activated. No additional reagents are required to generate knockout indels [12].

- CRISPRi/a: The dCas9-effector fusion proteins (e.g., dCas9-KRAB for i, dCas9-VP64 for a) will bind to the target site upon delivery and immediately begin repressing or activating transcription without altering the DNA sequence [15].

Step 4: Analysis and Validation of Edits

- Genotypic Validation: Confirm editing efficiency.

- For CRISPRko: Use the T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor assay to detect indels. Confirm with Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products or next-generation sequencing (NGS) [6].

- For CRISPRi/a: Since the DNA is not cut, sequencing is not used for validation. Instead, measure mRNA levels using qRT-PCR to confirm knockdown or activation. Protein-level validation via western blotting is highly recommended [16].

- Phenotypic Validation: Perform functional assays relevant to your gene and biological question (e.g., proliferation assays, flow cytometry for surface markers, differentiation assays).

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My editing efficiency is low. What can I do to improve it?

- Cause: Poor gRNA design or low activity [6].

- Cause: Inefficient delivery of CRISPR components [6].

- Solution: Optimize your delivery method. For electroporation, titrate voltage and pulse length. For lipofection, test different lipid reagents. Consider using an RNP complex for more immediate and efficient activity [12]. Enrich for transfected cells by adding antibiotic selection or FACS sorting [17].

- Cause: The Cas9 nuclease or dCas9 effector is not expressing well.

- Solution: Confirm that the promoter driving Cas9/dCas9 expression is suitable for your cell type. Use codon-optimized versions of Cas9 for your host organism [6].

Q2: I suspect there are off-target effects. How can I minimize and detect them?

- Cause: The gRNA binds to and cleaves/modifies sequences with high similarity to the target.

- Prevention: Design gRNAs with high specificity using multiple prediction algorithms [11] [6]. Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) that have been engineered to reduce off-target cleavage [6]. For CRISPRko, using RNP complexes instead of plasmid DNA can reduce the temporal window for off-target activity [12].

- Detection: Perform whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on edited clones for a comprehensive view. Alternatively, use targeted sequencing of in silico predicted off-target sites.

Q3: For CRISPRko, I see a mixture of edited and unedited cells (mosaicism). How can I address this?

- Cause: Editing occurred after the target cells had already divided.

- Solution: To isolate a pure population, perform single-cell cloning (limiting dilution or FACS sorting) from the edited cell pool. Genotype individual clones to identify those with homogeneous edits [6].

Q4: My CRISPRi/a experiment is not showing the expected transcriptional change. What's wrong?

- Cause: The gRNA is not targeted to the optimal regulatory region.

- Cause: The dCas9-effector fusion is not potent enough.

- Solution: Use enhanced effector systems. For CRISPRi, dCas9-KRAB is standard. For CRISPRa, consider stronger synthetic activators like the SunTag system or VPR (VP64-p65-Rta) fusion [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 / dCas9 Effector Proteins | CRISPRko: Creates DSBs.CRISPRi/a: Serves as a targeting scaffold. | Use wild-type Cas9 for KO. Use dCas9 fused to KRAB (i) or VP64 (a) domains. High-fidelity variants reduce off-targets [6]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs the Cas/dCas protein to the specific DNA target sequence. | Chemically modified sgRNAs can increase stability and editing efficiency [12]. |

| Delivery Vectors/Reagents | Introduces CRISPR components into cells. | Plasmids/Lentivirus: For stable expression. RNP + Electroporation: For high efficiency and minimal off-targets [12]. |

| Selection Markers | Enriches for successfully transfected/transduced cells. | Puromycin is commonly used. Adding selection or FACS sorting improves editing efficiency [17]. |

| Genomic DNA Isolation Kit | Provides high-quality DNA for genotyping analysis. | Essential for post-editing validation. |

| Validation Assays | Confirms genetic and phenotypic edits. | T7E1/Surveyor Assay: For indel detection (KO). qRT-PCR: For transcript level changes (i/a). NGS: For comprehensive analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When should I choose CRISPRi over CRISPRko for a loss-of-function study?

A: Choose CRISPRi when studying essential genes, as a complete knockout might be lethal to the cell, preventing analysis. CRISPRi's reversible knockdown allows you to study the temporal effects of gene silencing. It is also preferable when you want to model partial loss-of-function or hypomorphic alleles [15].

Q: Can I use the same gRNA for CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa?

A: Not optimally. While a gRNA designed for CRISPRko might bind successfully in a CRISPRi/a context, its efficiency can vary. gRNAs for CRISPRko are designed to target coding exons and are selected for minimal off-targets across the genome. gRNAs for CRISPRi and CRISPRa are specifically designed to bind promoter regions and are optimized for their position relative to the transcriptional start site to maximize transcriptional modulation [16] [15].

Q: What are the primary regulatory and safety considerations when working with these systems?

A: All work should adhere to institutional biosafety committee (IBC) guidelines. A key consideration, especially for CRISPRko, is the potential for off-target effects and their impact on data interpretation and therapeutic applications [13] [6]. For any research with therapeutic potential, rigorous validation and adherence to evolving FDA/EMA guidelines on gene therapies are critical [13]. The use of lentiviral delivery systems requires appropriate biosafety level (BSL-2) containment.

This technical support guide addresses common questions and challenges in pooled CRISPR screening, providing standardized protocols and troubleshooting advice to ensure robust and reproducible results for functional genomics research.

Core Concepts and Library Design

What are the essential design principles for a genome-wide sgRNA library?

A well-designed sgRNA library is the foundation of a successful pooled CRISPR screen. The key is to maximize on-target efficiency while minimizing off-target effects.

Table 1: Comparison of Publicly Available Genome-Wide sgRNA Libraries [18]

| Library Name | Average Guides per Gene | Reported Performance in Essentiality Screens |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna-single (top3-VBC) | 3 | Strongest depletion of essential genes; performs as well or better than larger libraries. |

| Yusa v3 | 6 | Consistently one of the weaker-performing libraries in benchmark tests. |

| Croatan | 10 | One of the best-performing libraries, but larger in size. |

| MinLib-Cas9 (2-guide) | 2 | Incomplete benchmark data suggests it may be a top performer. |

Key design principles include:

- Guide Quantity and Quality: While traditional libraries use 4 or more guides per gene, newer, more efficient designs like the Vienna library (using the top 3 guides per gene selected by VBC scores) demonstrate that smaller libraries can preserve or even enhance sensitivity and specificity [18].

- Dual vs. Single Targeting: Dual-targeting libraries, where two sgRNAs target the same gene, can create more effective knockouts and show stronger depletion of essential genes. However, they may also trigger a heightened DNA damage response, as evidenced by a fitness reduction even in non-essential genes. This strategy is promising for library compression but requires caution [18].

- Control Elements: Libraries must include both positive and negative controls. Non-targeting control (NTC) guides are essential for establishing a baseline, while sgRNAs targeting known essential genes serve as positive controls for assay performance [18] [19].

How do I choose between a single-targeting and a dual-targeting library?

The choice depends on your experimental goals and model system.

Table 2: Single vs. Dual-Targeting sgRNA Library Strategy [18]

| Consideration | Single-Targeting Library | Dual-Targeting Library |

|---|---|---|

| Knockout Efficiency | Good, but depends on individual guide efficiency. | Superior; dual guides can create deletions for more effective knockouts. |

| Library Size | Larger, as it requires more guides for confidence. | Can be smaller, enabling screening in complex models. |

| Potential Pitfalls | Variable performance between guides for the same gene. | Possible fitness cost from increased DNA damage. |

| Ideal Use Case | Standard in vitro screens with ample cell numbers. | Screens with limited material (e.g., in vivo, organoids). |

Experimental Setup and Execution

What controls are critical for a pooled CRISPR screen?

Including the correct controls is non-negotiable for validating your screen and interpreting results [19].

- Positive Editing Controls: These are validated sgRNAs with known high editing efficiency, often targeting common genes like TRAC or RELA in human cells. They confirm that your transfection and editing conditions are working optimally [19].

- Negative Editing Controls: These establish the baseline cellular behavior and help distinguish true phenotype from experimental noise. Options include:

- Mock Control: Cells subjected to the transfection stress (e.g., electroporation) without receiving any CRISPR components. This controls for effects caused by the delivery process itself [19].

What is the recommended sequencing depth and coverage for a genome-wide screen?

Achieving sufficient sequencing depth and cellular coverage is critical to avoid stochastic noise and false positives.

- Sequencing Depth: It is generally recommended to sequence each sample to a depth of at least 200x per sgRNA. For a typical genome-wide library, this often translates to roughly 10 Gb of sequencing data per sample [20].

- Cellular Coverage: The gold standard for in vitro Cas9 knockout screens is to have at least 250-500 cells per sgRNA in your library at the start of the screen. This ensures each guide is adequately represented to withstand bottlenecks and drift [21]. However, note that for in vivo screens, achieving this coverage is often challenging due to engraftment bottlenecks [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Why do I see high variability between different sgRNAs targeting the same gene?

This is a common observation due to the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence, which lead to variable editing efficiencies [20]. Some guides simply work better than others. This is precisely why designing libraries with multiple sgRNAs (e.g., 3-4) per gene is crucial—it mitigates the impact of a single underperforming guide and provides a more robust, gene-level signal [20].

What should I do if no significant gene enrichment or depletion is observed?

The absence of significant hits is more often a problem of insufficient selection pressure rather than a statistical error [20]. If the selective pressure applied to the cells is too mild, the phenotypic difference between cells with different knockouts will be too small to detect. To address this, you should optimize your screen by increasing the selection pressure (e.g., a higher drug concentration) and/or extending the duration of the screen to allow for greater enrichment or depletion of specific sgRNAs [20].

If sequencing shows a large loss of sgRNAs, what does this indicate?

This depends on when the loss occurs [20]:

- In the initial library cell pool: This indicates insufficient initial sgRNA representation. The library pool must be re-established with a higher complexity to ensure all guides are present before selection begins.

- In the final experimental sample: This likely reflects excessive selection pressure, which has caused the loss of many guides and their corresponding cells. The selection conditions should be re-titrated to a less stringent level [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Pooled CRISPR Screening [19] [23] [24]

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Validated Positive Control sgRNAs | Essential for optimizing transfection and confirming editing efficiency (e.g., targeting human TRAC or mouse ROSA26) [19]. |

| Non-Targeting Control (NTC) sgRNAs | Critical for establishing a baseline and identifying false positives caused by the screening process [19]. |

| Chemically Modified Synthetic sgRNAs | Improves guide stability, increases editing efficiency, and reduces immune stimulation compared to in vitro transcribed (IVT) guides [24]. |

| Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) | Complexing Cas9 protein with sgRNA into an RNP allows for high-efficiency, "DNA-free" editing and can reduce off-target effects [24]. |

| Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Kits | Enables high-resolution, multiomic readouts of perturbation effects (transcriptome, surface proteins, and guide identity) in single cells [23]. |

Standardized Pooled CRISPR Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a standardized pooled CRISPR screening workflow, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology has revolutionized genetic research and therapeutic development. For researchers and drug development professionals working to standardize CRISPR screening workflows, understanding the capabilities and limitations of the available tools—from classic Cas9 nucleases to advanced base and prime editors—is fundamental. This guide provides a technical overview and troubleshooting resource for the most commonly used CRISPR genome editors, focusing on their mechanisms, applications, and solutions to common experimental challenges.

The Core Toolkit: Types of CRISPR Genome Editors

The CRISPR toolkit has expanded significantly beyond the original Cas9 nuclease. The table below summarizes the key types of editors, their mechanisms, and primary applications.

Table: Comparison of Major CRISPR Genome-Editing Tools

| Editor Type | Core Components | Editing Mechanism | Primary Editing Outcomes | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Cas9 enzyme, sgRNA | Creates Double-Strand Breaks (DSBs) [1] | Indels via NHEJ; precise edits via HDR with a template [25] | Simple, effective gene knockout | Functional gene knockout, gene insertion (with HDR) |

| Base Editors (BEs) | Cas9 nickase fused to deaminase enzyme, sgRNA [26] | Chemical conversion of one base to another without DSBs [26] | C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C conversions [27] | High efficiency, no DSBs, low indels | Disease modeling, correcting point mutations |

| Prime Editors (PEs) | Cas9 nickase fused to Reverse Transcriptase, pegRNA [26] | "Search-and-replace" using RT and pegRNA template without DSBs [26] | All 12 base-to-base conversions, small insertions, deletions [26] | Unprecedented precision, broad editing scope, no DSBs | Correcting a wide range of pathogenic mutations |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms of these three core editor types.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: How can I improve the efficiency of my prime editing experiments?

Low editing efficiency is a common hurdle with prime editing. The following solutions are recommended:

- Use Updated PE Systems: The efficiency of prime editing has improved with successive versions. If using an older system (e.g., PE1 or PE2), upgrade to PE3, PE4, or PE5. These systems incorporate additional strategies like nicking the non-edited strand (PE3) or suppressing the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway (PE4/PE5) to significantly boost efficiency [26].

- Optimize pegRNA Design: The pegRNA is critical. Use specialized bioinformatics tools to design pegRNAs with optimal length for the reverse transcriptase template (RTT) and primer binding site (PBS). Consider using engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) that include structured RNA motifs to enhance stability and reduce degradation [26].

- Modulate Cellular Repair Pathways: Co-expressing a dominant-negative MMR protein (MLH1dn) can increase prime editing efficiency by up to ~70% in HEK293T cells, as seen in PE4 and PE5 systems. This prevents the cell from rejecting the newly edited strand [26].

Table: Evolution of Prime Editor Systems and Their Efficiencies

| Prime Editor Version | Key Features and Modifications | Reported Editing Frequency (in HEK293T cells) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Original version; Cas9 nickase (H840A) fused to M-MLV RT | ~10–20% | [26] |

| PE2 | Optimized reverse transcriptase for higher stability and processivity | ~20–40% | [26] |

| PE3 | PE2 + additional sgRNA to nick the non-edited strand | ~30–50% | [26] |

| PE4 | PE2 + dominant-negative MLH1 to inhibit mismatch repair | ~50–70% | [26] |

| PE5 | PE3 + dominant-negative MLH1 to inhibit mismatch repair | ~60–80% | [26] |

| PE6 & PE7 | Compact RT variants, stabilized epegRNAs, La protein fusion | ~70–95% | [26] |

FAQ 2: What can I do to minimize off-target effects?

Off-target editing remains a critical concern for all therapeutic applications.

- Choose High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Wild-type SpCas9 is prone to off-target effects. Use engineered high-fidelity variants like eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, or HypaCas9. These versions have mutations that reduce non-specific interactions with DNA [25].

- Utilize Cas Nickases: For edits requiring HDR, use a pair of Cas9 nickases (D10A mutation) that target opposite strands. A DSB is only formed when both nickases bind in close proximity, dramatically increasing specificity [25].

- Select Optimal gRNAs with Bioinformatics Tools: Always design gRNAs using rigorous computational tools. Software like CHOPCHOP and Cas-OFFinder can help select gRNAs with maximal on-target and minimal off-target activity by scanning the genome for similar sequences [11].

- Delivery Method Matters: Transient delivery of CRISPR components as ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) instead of using plasmid DNA that leads to prolonged expression can reduce off-target effects [27].

FAQ 3: Which delivery method should I use for my experiment?

The choice of delivery method is crucial and depends on the application (in vivo vs. in vitro) and the target cell type.

- In Vitro Delivery to Cultured Cells:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Highly effective for delivering CRISPR RNPs or mRNA to a wide range of cell types, including primary cells [7].

- Viral Vectors (Lentivirus, AAV): Provide high transduction efficiency but have limitations. AAV has a small packaging capacity, making it unsuitable for large Cas9 orthologues, and viral vectors can trigger immune responses [27].

- In Vivo Therapeutic Delivery:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): The leading non-viral platform for systemic in vivo delivery. LNPs naturally accumulate in the liver, making them ideal for targeting liver-specific diseases, as demonstrated in clinical trials for hATTR and HAE [7]. A key advantage is the potential for re-dosing, which is difficult with viral vectors [7].

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV): Widely used but has limitations on cargo size and can elicit immune responses. Often used for ex vivo therapies.

The decision flow for selecting a delivery method is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful CRISPR experiment relies on high-quality, well-characterized reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their functions.

Table: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Genome Editing Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Directs the Cas protein to the specific genomic target site. | Can be synthesized as crRNA+tracrRNA or as a single guide RNA (sgRNA). Quality is critical. |

| pegRNA | Specialized guide for Prime Editing; contains both targeting spacer and template for edit. | Design is more complex than sgRNA; requires optimization of PBS and RTT lengths [26]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Effector protein that creates a double-strand break at the target DNA. | Choose between wild-type (SpCas9), high-fidelity variants (SpCas9-HF1), or nickases (Cas9n). |

| Base Editor Protein | Fusion protein (e.g., Cas9 nickase-cytidine deaminase) for chemical base conversion. | Be aware of bystander editing within the activity window [26]. |

| Prime Editor Protein | Fusion protein (Cas9 nickase-Reverse Transcriptase) for precise template-driven edits. | Later versions (PE4, PE5, PE6) show dramatically improved efficiency [26]. |

| Delivery Vector | Plasmid, virus, or nanoparticle used to introduce CRISPR components into cells. | Choice affects kinetics and persistence; non-viral methods (LNPs, electroporation) are preferred for transient expression. |

| HDR Donor Template | DNA template containing the desired edit, used for precise repair after a DSB. | Can be single-stranded or double-stranded DNA; include homologous arms. |

| Validation Assays | Methods (e.g., Sanger sequencing, NGS, T7E1 assay) to confirm editing efficiency and specificity. | Essential for any experiment; use NGS for unbiased off-target assessment. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for a Prime Editing Experiment

This protocol outlines key steps for a prime editing experiment in cultured mammalian cells, based on the systems described in the literature [26].

Target Selection and pegRNA Design: Identify your target genomic locus. Design a pegRNA using a specialized tool. The pegRNA must contain:

- A spacer sequence (~20 nt) complementary to the target DNA.

- A primer binding site (PBS), typically 10-15 nucleotides long.

- A reverse transcription template (RTT) that encodes your desired edit.

Component Cloning: Clone your designed pegRNA sequence into an appropriate expression plasmid. Co-clone or obtain a separate plasmid expressing the prime editor protein (e.g., PE2, PE3, PE4).

Cell Transfection: Transfect your target cell line (e.g., HEK293T) with the prime editor and pegRNA plasmids (or deliver as mRNA and synthetic pegRNA). Include a negative control (cells only) and a non-targeting pegRNA control.

Harvest and DNA Extraction: Allow 48-72 hours for editing to occur. Harvest the cells and extract genomic DNA.

Efficiency Validation:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target genomic region by PCR.

- Sequencing Analysis: Subject the PCR product to Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify the percentage of alleles containing the desired edit.

Off-Target Assessment: Use in silico tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) to predict potential off-target sites. Amplify and sequence the top predicted off-target sites from the edited cell population to assess specificity.

Executing the Screen: From Experimental Design to High-Content Readouts

The following diagram illustrates the complete standardized workflow for a pooled CRISPR-Cas9 screening experiment, from initial library design to final hit identification.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Phase 1: Experimental Design and sgRNA Library

Library Design Principles:

- Design 6-8 sgRNAs per gene to ensure comprehensive coverage [28]

- Include both negative controls (non-targeting sgRNAs) and positive controls (sgRNAs targeting known essential genes) [28]

- For genome-wide screens, ensure library contains sufficient complexity (typically 100,000+ sgRNAs) [28]

Representation Calculation:

- Infect at least 500 cells per sgRNA to ensure statistical power [28]

- Maintain multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.3 to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA [28] [29]

- Calculate total cells needed based on: (Number of sgRNAs × 500) / MOI [28]

Phase 2: Library Transduction and Selection

Day 1-3: Cell Preparation

- Culture Cas9-expressing cells to 60-80% confluency [28]

- For lentiviral production, use approved biosafety level 2 facilities [28]

Day 4: Transduction

- Transduce cells with lentiviral sgRNA library at MOI of 0.3 in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL) [28] [29]

- Include untransduced control cells for selection optimization

Day 5-7: Selection

- Begin antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin 1-5 μg/mL) 24-48 hours post-transduction [29]

- Maintain selection until all control cells are dead (typically 3-7 days)

- Harvest pre-selection sample (T0) for reference by collecting ~5 million cells [29]

Phase 3: Phenotypic Selection and Passaging

Experimental Setup:

- Split transduced cells into experimental and control conditions

- Apply selective pressure (drug treatment, nutrient stress, etc.) to experimental condition

- Maintain control condition in normal growth medium

Cell Passaging:

- Passage cells at consistent densities to maintain logarithmic growth

- Ensure minimum of 16 cell doublings to allow phenotypic manifestation [29]

- Maintain cell representation of at least 500 cells per sgRNA at each passage [28]

Cell Harvest:

- Harvest minimum number of cells based on library representation requirements (Table 1)

- Pellet cells at 300 × g for 3 minutes at 20°C [29]

- Store dry cell pellets at -80°C or proceed to gDNA extraction

Phase 4: Genomic DNA Extraction and NGS Library Preparation

gDNA Extraction:

- Extract gDNA using commercial kits (e.g., PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit) [29]

- Do not process more than 5 million cells per spin column to prevent clogging [29]

- Elute gDNA in Molecular Grade Water, aiming for concentration ≥190 ng/μL [29]

PCR Amplification:

- Perform PCR amplification in decontaminated workstation to avoid cross-contamination [29]

- Use staggered primers with Illumina adapters to increase sequence diversity [29]

- Include sample barcodes for multiplex sequencing

Quality Control:

- Quantify DNA using Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit [29]

- Verify amplification by running 5 μL PCR product on 2% agarose gel [29]

- Purify PCR products using commercial purification kits

Critical Parameters and Calculations

Table 1: Library Representation Calculations for gDNA Extraction

| Library Size (sgRNAs) | Minimum Cells for 300X Coverage | Total gDNA Required | Parallel PCR Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000-2,000 | 760,000 | 4 μg | 1 |

| 3,000-3,500 | 2,300,000 | 12 μg | 3 |

| 5,000+ | 4,600,000 | 24 μg | 6 |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | Poor gRNA design or delivery | Verify gRNA targets unique genomic sequence; optimize delivery method for cell type [6] |

| High off-target effects | Non-specific gRNA binding | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants; design gRNAs with online prediction tools [6] |

| Cell toxicity | High CRISPR component concentration | Titrate component concentrations; use nuclear localization signals [6] |

| Mosaicism (mixed edited/unedited cells) | Suboptimal delivery timing | Synchronize cell cycle; use inducible Cas9 systems [6] |

| Inability to detect edits | Insensitive detection methods | Use T7 endonuclease I assay, Surveyor assay, or sequencing [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Lentiviral sgRNA pools, Saturn V library [29] | Delivers genetic perturbations | Maintain >1000X coverage of library size [28] |

| Cas9 Source | Stable Cas9 cell lines, Cas9-lentivirus co-delivery [28] | Executes genomic cutting | Verify Cas9 activity before screening |

| Delivery Tools | Lentivirus, electroporation, lipofection [6] | Introduces CRISPR components | Optimize for specific cell type; use MOI ~0.3 [28] |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, blasticidin, GFP sorting | Enriches for transduced cells | Determine optimal concentration beforehand |

| gDNA Extraction | PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit [29] | Isolates genomic DNA for NGS | Maximum 5 million cells per column [29] |

| Quantification | Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit [29] | Accurately measures DNA concentration | More accurate than spectrophotometry for gDNA |

| NGS Preparation | Herculase reagents, barcoded primers [29] | Amplifies sgRNA regions for sequencing | Perform in decontaminated workstation [29] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the minimum library representation required for a successful screen? A: For high-quality NGS results, maintain library representation of at least 300X, though higher coverage (500-1000X) provides more robust results [29]. This means having at least 300 cells per sgRNA in your population.

Q: How do I calculate the number of cells needed for my specific library? A: Use this formula: Minimum cells = (Number of sgRNAs in library × Desired coverage) / Transduction efficiency. For example, a 5,000 sgRNA library with 500X coverage and 30% transduction efficiency requires: (5,000 × 500) / 0.3 = 8.3 million cells [28] [29].

Q: What are the essential controls to include in my screen? A: Your screen should include: (1) Non-targeting negative control sgRNAs; (2) sgRNAs targeting genomic "safe harbor" regions; and (3) Positive control sgRNAs targeting known essential genes relevant to your phenotype [28].

Q: How long should the phenotypic selection phase last? A: Most screens require 14-21 days (approximately 16+ cell doublings) to allow sufficient time for phenotypic manifestation and sgRNA enrichment/depletion [29]. The exact duration depends on your specific experimental model and selection pressure.

Q: What sequencing depth is required for the NGS step? A: Aim for 100-200 reads per sgRNA to ensure accurate quantification of sgRNA abundance. For a 5,000 sgRNA library, this translates to 500,000-1,000,000 total reads per sample [29].

Core Advantages of RNP Delivery

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, which consist of a pre-assembled Cas protein and a guide RNA (sgRNA), offer a superior delivery format for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing compared to DNA- or RNA-based methods. The principal benefits stem from their transient activity and immediate functionality upon delivery.

- Enhanced Specificity and Reduced Off-Target Effects: RNP complexes enter the nucleus and become active almost immediately, but their activity is short-lived as they are rapidly degraded by cellular proteases. This brief window of activity—typically around 24 hours—significantly reduces the opportunity for the Cas9 nuclease to cut at unintended, off-target sites in the genome. Studies have consistently shown a 28-fold lower ratio of off-target to on-target mutations when using RNPs compared to plasmid DNA transfection [30].

- High Editing Efficiency and Precision: Because the functional complex is formed in vitro prior to delivery, RNPs bypass the need for intracellular transcription and translation. This leads to a faster onset of editing and more predictable results. The quality of both the Cas9 protein and the sgRNA can be verified before transfection, ensuring a highly precise and efficient complex [30].

- Improved Cell Viability and Reduced Cytotoxicity: Transfection with CRISPR components as plasmids can be stressful to cells and often leads to significant cytotoxicity. In contrast, delivery of pre-formed RNPs is notably less toxic. Experiments have demonstrated that cell viability remains significantly higher with RNP delivery, often above 80%, even in sensitive primary cells and stem cells [31] [30].

- Elimination of Genomic Integration Risk: Unlike plasmid-based systems, which carry a risk of random parts of the plasmid DNA integrating into the host genome, RNP delivery involves no DNA. This completely avoids the risk of insertional mutagenesis, a critical safety advantage for both basic research and therapeutic applications [30] [32].

Quantitative Comparison of CRISPR Delivery Formats

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of different CRISPR cargo formats, highlighting the distinct advantages of RNPs.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR Cargo Formats [30] [32]

| Feature | Plasmid DNA | mRNA + gRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Activity | Slow (24-48 hrs) | Moderate (12-24 hrs) | Fast (<4 hrs) |

| Duration of Activity | Prolonged (days to weeks) | Moderate (a few days) | Short (~24 hrs) |

| Typical Editing Efficiency | Variable, often lower | Moderate | High (often >70%) |

| Off-Target Effect Risk | High | Moderate | Low |

| Risk of Host Genome Integration | Yes | No | No |

| Cytotoxicity | High | Moderate | Low |

| Experimental Timeline | Longer | Moderate | Shorter (up to 50% faster) |

Experimental Protocol: RNP Delivery via Electroporation

This protocol details a standard method for delivering RNPs into mammalian cells via electroporation, a highly efficient physical delivery method.

Materials and Reagents

- Purified Cas9 protein (e.g., SpCas9)

- Chemically synthesized or in vitro transcribed target-specific sgRNA

- Electroporation buffer (compatible with your cell type, e.g., PBS or proprietary buffers)

- The cell line of interest (e.g., primary T cells, iPSCs, immortalized cell lines)

- Electroporation device and corresponding cuvettes

- Pre-warmed complete cell culture medium

Step-by-Step Procedure

RNP Complex Formation:

- Resuspend the sgRNA in nuclease-free buffer to a stock concentration of 100 µM.

- In a sterile microcentrifuge tube, combine purified Cas9 protein and the sgRNA at a molar ratio typically between 1:1 and 1:2 (Cas9:sgRNA). For example, mix 5 µg of Cas9 (~0.1 nmol) with a 1.2x molar excess of sgRNA.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow the RNP complex to form.

Cell Preparation:

- Harvest the target cells and wash them thoroughly with electroporation buffer to remove any residual media containing serum or antibiotics.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in electroporation buffer at a high concentration (e.g., 1-10 x 10^6 cells per 100 µL).

Electroporation:

- Combine the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex. Gently mix.

- Transfer the entire mixture into an electroporation cuvette.

- Electroporate the cells using the optimized electrical parameters (voltage, pulse length, number of pulses) for your specific cell type. For many primary cells, a single pulse of 1500-2500 V for 10-20 ms is effective.

Post-Transfection Recovery:

- Immediately after electroporation, transfer the cells from the cuvette into a pre-warmed culture plate containing complete medium.

- Incubate the cells at 37°C and 5% CO₂. Analyze editing efficiency, typically 48-72 hours post-electroporation, using methods like T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

Advanced RNP Delivery: Optimized Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

For in vivo applications, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) provide a potent and clinically relevant method for systemic RNP delivery. Recent research has focused on optimizing LNP formulations specifically for RNP encapsulation.

LNP Formulation Optimization

- Ionizable Lipids: Screening of ionizable cationic lipids is crucial. The lipid SM102 has been identified as highly effective for RNP delivery, leading to a dramatic increase in editing efficiency [33].

- Stability Enhancement: Encapsulating the pre-assembled RNP, rather than its individual components, within LNPs protects the complex from degradation. The inclusion of stabilizers like 10% (w/v) sucrose in the formulation further enhances RNP stability [33].

- Efficiency Gains: Optimized LNP-RNP formulations have demonstrated remarkable results, achieving in vivo editing efficiency enhancements larger than 300-fold compared to the delivery of naked RNP, without detectable off-target edits [33].

Diagram 1: LNP-RNP delivery workflow.

Troubleshooting Common RNP Delivery Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for RNP-Based Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency | RNP complex is unstable or degraded. | Verify protein and sgRNA quality. Form RNP complex immediately before use and use stabilizers like sucrose [33]. |

| Inefficient delivery into cells. | Optimize delivery parameters (e.g., voltage for electroporation, lipid ratios for LNPs). Consider different transfection reagents. | |

| Poor Cell Viability Post-Delivery | Excessive cytotoxicity from delivery method. | Titrate the RNP concentration to the lowest effective dose. For electroporation, optimize electrical parameters to reduce cell stress [32]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Variable RNP formation or delivery. | Standardize the RNP assembly protocol (incubation time, temperature, molar ratios). Ensure consistent cell quality and count. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: For which cell types is RNP delivery particularly advantageous? RNP delivery is highly beneficial for hard-to-transfect cells, including primary cells (like T-cells and hematopoietic stem cells), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and differentiated cells. Its high efficiency and low toxicity make it the preferred choice where cell health and precision are paramount [30] [32].

Q2: My RNP experiment is not yielding high editing efficiency. What should I check first? First, verify the quality and concentration of your Cas9 protein and sgRNA. Then, ensure your delivery method is optimized for your specific cell type. For electroporation, this means testing different voltage/pulse settings. For lipid-based methods, screen different reagents. Finally, titrate the RNP concentration to find the optimal dose for your experiment [30] [33].

Q3: Are there any downsides to using RNPs? The main challenges are the higher cost and more complex production of purified Cas9 protein compared to plasmids, and the relative instability of the protein complex, which requires careful handling and storage. However, the benefits of high efficiency, low off-targets, and superior safety often outweigh these limitations [32].

Q4: Can RNPs be used for homology-directed repair (HDR) or knock-in experiments? Yes. In fact, RNP delivery is excellent for HDR-based knock-in. The rapid and transient activity of RNPs creates a defined window for the Cas9 cut, which can be strategically timed with the delivery of a donor DNA template to enhance the relative efficiency of HDR over the error-prone NHEJ pathway [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RNP Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNP-Based CRISPR Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Cas9 Nuclease | The enzyme component of the RNP complex that performs the DNA cleavage. | Opt for high-purity, endotoxin-free grades. Cas9 variants with higher fidelity (e.g., HiFi Cas9) can further reduce off-target effects. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | The guide RNA that directs Cas9 to the specific genomic target. | Chemically synthesized sgRNA offers high consistency and allows for chemical modifications to enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity. |

| Electroporation System | A physical method to introduce RNPs into cells by creating temporary pores in the cell membrane. | Systems like the Neon (Thermo Fisher) or Nucleofector (Lonza) are industry standards. Cell-type-specific kits are available. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic nanocarriers for efficient in vivo RNP delivery. | Formulations must be optimized for RNP encapsulation. The ionizable lipid SM102 has shown high efficacy in recent studies [33]. |

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., Ppoly) | A class of non-viral delivery vehicles that can form stable complexes with RNPs via electrostatic interactions. | A modified cationic hyper-branched cyclodextrin-based polymer (Ppoly) has shown >90% encapsulation efficiency and minimal cytotoxicity [31]. |

What are the fundamental differences between Perturb-seq and CROP-seq?

Both Perturb-seq and CROP-seq are pioneering single-cell CRISPR screening methods that combine pooled CRISPR perturbations with single-cell RNA sequencing. They enable researchers to investigate functional genetic screening at single-cell resolution by linking guide RNA (gRNA) identities to transcriptomic profiles in individual cells. The key technical difference lies in how they capture the gRNA information [34].

Perturb-seq initially utilized indirect gRNA capture through polyadenylated barcode sequences. This approach placed a separate barcode with a poly-A tail on the lentiviral vector, which was captured alongside cellular mRNAs during standard single-cell RNA sequencing workflows. However, this method suffered from a significant limitation: the physical distance (approximately 2.5 kb) between the gRNA and its barcode sequence led to high "barcode-swapping" frequencies due to lentiviral recombination. This resulted in misassignment of gRNAs to cells, with approximately 50% of all gRNAs affected in early Perturb-seq implementations [34].

CROP-seq introduced a more integrated approach by engineering a polyadenylated gRNA transcript. The CROP-seq vector produces two transcripts: the functional gRNA (driven by a U6 promoter) and a separate transcript that includes both a selection cassette and the gRNA sequence, driven by an EF1a promoter. This design allows the gRNA itself to be detected in standard single-cell assays that capture poly-A tails without requiring specialized capture sequences [35].

Modern implementations, particularly commercial platforms, have evolved to use direct gRNA capture through Feature Barcode technology. This approach adds specific capture sequences directly to the sgRNA scaffold, enabling dedicated capture and sequencing of gRNAs separately from the transcriptome. This method eliminates barcode-swapping issues and reduces sequencing burdens compared to CROP-seq [23].

Method Comparison & Selection Guide

Table: Comparison of Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Methods

| Method | gRNA Capture Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Perturb-seq | Indirect capture via polyadenylated barcode | Compatible with standard scRNA-seq | High barcode-swapping rates (~50%) [34] | Historical reference only |

| CROP-seq | Polyadenylated gRNA transcript | No special capture sequences needed; all-in-one vector [35] | gRNA detection requires deeper transcriptome sequencing [23] | Academic labs with standard scRNA-seq capabilities |

| Direct Capture Perturb-seq | Feature Barcode technology | Minimal barcode swapping; separate CRISPR library reduces sequencing burden [23] | Requires capture sequence integration for 3' assays [23] | High-precision perturbation studies |

| 10x Genomics 5' CRISPR Screening | Direct capture of native gRNAs | Compatible with existing CRISPR libraries; multi-ome capability (transcriptome + surface proteins) [23] | Platform-specific | Studies requiring multi-omic readouts or using existing gRNA libraries |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guide

Experimental Design FAQs

What cellular processes are best suited for single-cell CRISPR screening?

Single-cell CRISPR screening is most effective when studying cell-autonomous processes with clear transcriptional phenotypes. The perturbation should primarily affect the cell's own phenotype rather than depending on interacting cells. Ideal applications include: transcription factor networks, signaling pathway activation, differentiation trajectories, and metabolic reprogramming. Processes with minimal transcriptional signatures (e.g., cell death mechanisms without characteristic gene expression changes) are less suitable [23].

How many cells and guides should I plan for my experiment?

For homogeneous sample types, plan for approximately 100 cells per gene to achieve sufficient statistical power. Scale your cell numbers accordingly—for thousands of genes, you'll need hundreds of thousands of cells. A single high-throughput run can analyze up to 320,000 cells, sufficient for approximately 3,200 genes [23].

Common Technical Issues & Solutions

Problem: Low gRNA detection efficiency

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control steps during library preparation. Verify perturbation effect size in bulk before single-cell analysis. For CROP-seq, ensure adequate sequencing depth for transcriptome libraries to detect gRNAs [35] [36].

Problem: High noise and sparse data in scRNA-seq readouts

- Solution: Use computational tools like MUSIC that incorporate data imputation (SAVER) and specialized filtering. Filter out perturbed cells with invalid edits and perturbations with insufficient cells per guide (recommended minimum varies by experiment scale) [36].

Problem: Inaccurate gRNA-to-cell assignment

- Solution: For new experiments, choose direct capture methods (Feature Barcoding) over indirect capture to avoid barcode-swapping issues. If using historical Perturb-seq data, employ computational correction methods that account for swapping rates [34].

Problem: Weak perturbation effects

- Solution: Optimize gRNA design for efficiency. Consider alternative CRISPR modalities: CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB) for enhanced repression, especially at regulatory elements; CRISPRa (dCas9-activators) for gene activation [35].

Experimental Protocols

Essential Protocol: CROP-seq Workflow

- Vector Design: Clone sgRNAs into the CROP-seq vector containing both U6-driven sgRNA and EF1a-driven selection cassette [35].

- Library Generation: Produce lentiviral sgRNA library at appropriate titer to ensure single integration events.

- Cell Transduction: Transduce Cas9-expressing cells at low MOI (<0.3) to ensure most cells receive single guides.

- Selection: Apply appropriate selection (e.g., puromycin) 24-48 hours post-transduction.

- Single-Cell Processing: Prepare single-cell suspensions for 3' scRNA-seq platforms.

- Library Sequencing: Sequence both transcriptome and gRNA libraries. For CROP-seq, sequence transcriptome library deeply enough to detect gRNAs [23].

Essential Protocol: Direct Capture Perturb-seq

- Library Design: Design sgRNAs with appropriate capture sequences for your platform (if using 3' assays) or use existing libraries (for 5' assays) [23].

- Cell Processing: Follow standard single-cell suspension protocols for your platform (10x Genomics 5' or 3').

- Library Preparation: Prepare separate libraries for gene expression and CRISPR guides using Feature Barcode technology.

- Sequencing: Balance sequencing depth between gene expression and CRISPR libraries based on platform recommendations.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The analysis of single-cell CRISPR screening data presents unique computational challenges, including data sparsity, technical noise, and the need to link perturbations to transcriptional outcomes [36]. Below is a generalized workflow for data analysis:

Key Computational Tools:

- MUSIC: An integrated pipeline for model-based understanding of single-cell CRISPR screening data that uses topic models to quantify perturbation effects [36].

- CellOT: A neural optimal transport framework for predicting single-cell perturbation responses by learning maps between control and perturbed cell states [37].

- GLiMMIRS: A generalized linear modeling framework for interrogating enhancer effects from single-cell CRISPR experiments [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Single-Cell CRISPR Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Vectors | CROP-seq plasmid, Perturb-seq vectors | Deliver sgRNA and enable detection in single-cell assays | CROP-seq: all-in-one design; Perturb-seq: requires separate barcode design [35] |

| gRNA Libraries | Custom-designed sgRNA libraries | Target genes of interest with minimal off-target effects | Genome-wide or focused designs; efficiency validation critical [39] |

| Cas9 Variants | Wild-type Cas9, dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi), dCas9-activator (CRISPRa) | Enable knockout, inhibition, or activation | CRISPRi preferred for regulatory elements; CRISPRa for gene activation [35] |

| Capture Reagents | Feature Barcode oligos, poly-dT primers | Enable gRNA detection in single-cell platforms | Direct capture reduces barcode swapping [23] |

| Cell Preparation Kits | Single-cell suspension kits, viability stains | Ensure high cell quality and recovery | Critical for data quality; >85% viability recommended |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for CRISPR Screening

Q1: Why are my CRISPR screening results different from the expected or published outcomes?

Several factors can cause discrepancies in your results. A common issue is inconsistent data processing. Differences in parameters during sequencing adapter trimming, such as those set in tools like CutAdapt, can significantly alter downstream results [40]. Furthermore, using a subset of sequencing data for practice instead of the full dataset for final analysis will not yield the same graphics or enrichment results [40]. Finally, a low signal, where no significant gene enrichment is observed, is often not a statistical error but a result of insufficient selection pressure during the screening process. Increasing the selection pressure or extending the screening duration can help enrich for meaningful phenotypes [20].

Q2: How much sequencing depth is required for a reliable CRISPR screen?

Achieving adequate sequencing depth is critical for data quality. It is generally recommended to aim for a sequencing depth of at least 200x for each sample [20]. The required data volume can be calculated using the formula: Required Data Volume = Sequencing Depth × Library Coverage × Number of sgRNAs / Mapping Rate. For example, a typical human whole-genome knockout library might require approximately 10 Gb of sequencing data per sample [20].

Q3: Is a low mapping rate a concern for the reliability of my screening results?

A low mapping rate itself does not necessarily compromise the reliability of your results. The analysis pipeline focuses only on the reads that successfully map to the sgRNA library, excluding unmapped reads. The key concern is to ensure the absolute number of mapped reads is sufficient to maintain the recommended sequencing depth (≥200x). Insufficient data volume, not the mapping rate percentage, is what introduces variability and reduces accuracy [20].

Q4: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance?

Editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence. Some sgRNAs may exhibit little to no activity due to their specific sequence context [20]. To ensure robust and reliable results, it is recommended to design at least 3–4 sgRNAs per gene. This strategy mitigates the impact of variability from any single, poorly performing sgRNA [20].

Q5: How can I determine if my CRISPR screen was successful?

The most reliable method is to include well-validated positive-control genes and their corresponding sgRNAs in your library. If these controls are significantly enriched or depleted as expected, it strongly indicates effective screening conditions [20]. In the absence of known controls, you can evaluate performance by assessing the cellular response to selection pressure (e.g., degree of cell death) and examining bioinformatics outputs, such as the distribution and log-fold change of sgRNA abundance [20].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Large Loss of sgRNAs in Sequencing Results

Problem: A substantial number of sgRNAs are missing from the sequencing data. Solution: The solution depends on when the loss occurs [20]:

- If the loss is in the initial library cell pool: This indicates insufficient initial sgRNA representation. You should re-establish the CRISPR library cell pool with adequate coverage to ensure all genes are represented.

- If the loss occurs in the experimental group after screening: This suggests excessive selection pressure was applied. You should optimize the screening conditions to reduce the pressure.

Issue 2: Interpreting Unexpected Log-Fold Change (LFC) Values

Problem: Positive LFC values appear in a negative screen (where sgRNAs should be depleted), or negative LFC values appear in a positive screen (where sgRNAs should be enriched). Solution: This can occur due to the statistical method used. When the Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) algorithm calculates the gene-level LFC as the median of its sgRNA-level LFCs, extreme values from individual sgRNAs can skew the results and produce unexpected signs [20]. Inspecting the behavior of individual sgRNAs for the gene of interest is recommended.

Issue 3: Low or No Significant Gene Enrichment

Problem: The screen fails to identify any genes that are significantly enriched or depleted. Solution: This is typically caused by insufficient selection pressure [20]. The experimental group may not have exhibited a strong enough phenotype to distinguish from controls.

- Remedy: Increase the selection pressure (e.g., higher drug concentration, longer antibiotic treatment) and/or extend the duration of the screen to allow for greater enrichment of cells with the desired phenotype.

Key Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

CRISPR Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a CRISPR knockout screen, from library design to hit identification.

Distinguishing Between Positive and Negative Screening

Understanding your screening goal is fundamental to experimental design and data interpretation.

| Screening Type | Selection Pressure | Phenotypic Goal | sgRNA/Gene Outcome in Surviving Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Screening | Relatively mild; only a small subset of cells die [20] | Identify genes essential for cell survival under the condition [20] | Depleted [20] |

| Positive Screening | Strong; most cells die, a small number survive [20] | Identify genes whose disruption confers a selective advantage (e.g., resistance) [20] | Enriched [20] |

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

A successful screen relies on high-quality, well-validated reagents.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Collection of guides targeting genes of interest; the core of the screen. | Ensure >99% library coverage and low coefficient of variation (<10%) in the cell pool [20]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Executes the genomic cut. Can be delivered as plasmid, ribonucleoprotein (RNP), etc. | High-efficiency delivery is critical. For in vivo screens, consider delivery methods like Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [7]. |

| Cell Line | The biological system for the screen. | Use a well-characterized line with high transduction efficiency. iPSC-derived cells are used for disease modeling [41]. |

| Selection Agents | Apply the pressure to select for a phenotype (e.g., antibiotics, drugs). | Titrate concentration and duration to avoid overly harsh (total sgRNA loss) or weak (no enrichment) pressure [20]. |

| GMP-Grade Reagents | Cas nuclease and gRNAs manufactured for clinical use. | Essential for therapeutic development. Ensure suppliers provide "true GMP," not just "GMP-like" materials [8]. |

Data Analysis Tools and Candidate Gene Selection

The table below summarizes common tools and strategies for analyzing CRISPR screening data.

| Tool / Metric | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MAGeCK | A widely used tool for analyzing genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens [20]. | Incorporates RRA (for single-condition comparisons) and MLE (for multi-condition modeling) algorithms [20]. |

| RRA Score | A composite score from the RRA algorithm that provides a comprehensive ranking of genes [20]. | Prioritize candidate genes based on this rank. Genes with higher ranks (lower RRA scores) are more likely to be true hits [20]. |

| LFC & p-value | Traditional metrics for selecting differentially represented genes. | Allows explicit cutoff setting but may yield a higher proportion of false positives compared to RRA rank-based selection [20]. |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Pathway Identification Logic

CRISPR screens can reveal entire functional pathways. The diagram below outlines the logical process of going from a list of candidate genes to an identified signaling pathway.

Application in Cancer Target Discovery

CRISPR screening has proven powerful in identifying novel therapeutic targets for cancers. For example:

- In metastatic uveal melanoma, a CRISPR-Cas9 screen targeting chromatin regulators identified SETDB1 as essential for cancer cell survival. Its inhibition curtailed tumor growth, establishing it as a promising therapeutic target [42].

- In prostate cancer, a genome-scale CRISPRi screen using a live-cell androgen receptor (AR) reporter identified PTGES3 as a key modulator of AR protein stability. Targeting PTGES3 destabilized AR and induced cell death, positioning it as a potential target to overcome treatment resistance [42].

- In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), genome-wide screens identified the XPO7-NPAT pathway as a critical vulnerability in TP53-mutated cases, revealing a target for a notoriously resistant cancer [42].

Integration with Single-Cell Technologies

The convergence of CRISPR screening with single-cell multi-omics technologies (e.g., scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq) allows for the systematic investigation of gene function and perturbation effects at an unprecedented resolution [43]. This integration enables the identification of complex gene regulatory networks and cellular responses in heterogeneous populations, providing deeper insights into disease mechanisms and potential drug targets [43].

Enhancing Screen Performance: A Guide to Troubleshooting and Optimization

Core Guide RNA Design Principles

Q: What are the most critical factors to consider when designing a guide RNA for a gene knockout experiment?

A successful gene knockout (KO) experiment relies on generating frameshift mutations that disrupt protein function. The target site selection for your guide RNA (gRNA) is paramount [44].

- Target Early, Common Exons: To maximize the probability of a complete knockout, design your gRNA to target an exon that appears early in the gene sequence and is common to all major protein-coding isoforms [45] [44]. Targeting too close to the N- or C-terminus should be avoided, as the cell might find an alternative start codon or the edited region may code for a non-essential part of the protein [44].

- Maximize On-Target Activity: Use established scoring algorithms like the "Doench rules" to predict gRNA sequences with high on-target activity. These rules are implemented in modern design tools and help select guides with the highest likelihood of efficient cutting [44].

- Minimize Off-Target Effects: A key step in design is to computationally assess the gRNA sequence for potential off-target binding sites across the genome. Tools can compare the gRNA sequence with the rest of the genome to predict and limit unintended cuts, which is crucial for experimental validity [45] [44].

Q: How does the experimental goal influence gRNA design strategy?

The "perfect" gRNA does not exist; its design is heavily dependent on your final application [44]. The table below summarizes the key considerations for different experiment types.