Batch Effect Correction in Genomic Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of batch effects in genomic data analysis.

Batch Effect Correction in Genomic Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of batch effects in genomic data analysis. It covers foundational concepts, explores method-specific correction strategies for diverse data types including RNA-seq, single-cell, DNA methylation, and proteomics, discusses troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and delivers a comparative analysis of leading correction tools. By synthesizing the latest methodologies and validation frameworks, this guide aims to empower scientists to enhance data reliability, improve reproducibility, and ensure the biological validity of their genomic findings.

What Are Batch Effects? Diagnosing Technical Noise in Your Genomic Datasets

FAQs on Batch Effects

1. What is a batch effect? A batch effect is a form of non-biological variation introduced into high-throughput data due to technical differences when samples are processed and measured in separate groups or "batches." These variations are unrelated to the biological question under investigation but can systematically alter the measurements, potentially leading to inaccurate conclusions [1] [2].

2. What are the most common causes of batch effects? Batch effects can arise at virtually every stage of an experiment. Key sources include [1] [2]:

- Reagent Lots: Using different batches or lots of chemicals and kits.

- Personnel: Differences in technique between individual researchers.

- Instrumentation: Using different machines or sequencers for measurement.

- Laboratory Conditions: Fluctuations in temperature, humidity, or other environmental factors.

- Time: Conducting experiments on different days or over extended periods.

- Protocols: Variations in sample preparation, storage, or analysis pipelines.

3. Why are batch effects particularly problematic in single-cell and multi-omics studies? Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data is especially prone to strong batch effects due to its inherently low RNA input, high dropout rates (where a gene is expressed but not detected), and significant cell-to-cell variation [2] [3]. In multi-omics studies, which integrate data from different platforms (e.g., genomics, proteomics), the challenge is magnified because batch effects can have different distributions and scales across data types, making integration difficult [2].

4. Can batch effects really lead to serious consequences? Yes, the impact can be profound. In one clinical trial, a change in the RNA-extraction solution introduced a batch effect that led to an incorrect gene-based risk calculation. This resulted in 162 patients being misclassified, 28 of whom received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy [2]. Batch effects are also a paramount factor contributing to the irreproducibility of scientific findings, sometimes leading to retracted papers and financial losses [2].

5. Is it better to correct for batch effects computationally or during experimental design? Prevention during experimental design is always superior. The most effective strategy is to minimize the potential for batch effects by randomizing samples and balancing biological groups across batches [1] [4]. Computational correction is a necessary tool when prevention is not possible, but it should not be relied upon as a primary solution, especially in unbalanced designs where it can inadvertently remove biological signal [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Batch Effects in Your Dataset

Before attempting any correction, you must first identify if batch effects are present.

- Objective: To visually and statistically assess the presence of technical variation across batches.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Begin with your normalized gene expression matrix (e.g., counts per million - CPM for RNA-seq).

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the dataset.

- Visualization: Create a PCA plot where samples are colored by their batch identifier (e.g., sequencing run, processing date) and, separately, by their biological group (e.g., disease vs. control).

- Interpretation: If samples cluster more strongly by batch than by biological group in the PCA plot, a significant batch effect is likely present [5]. For a more quantitative assessment, statistical tests like the k-nearest neighbor batch-effect test (kBET) can be used [3].

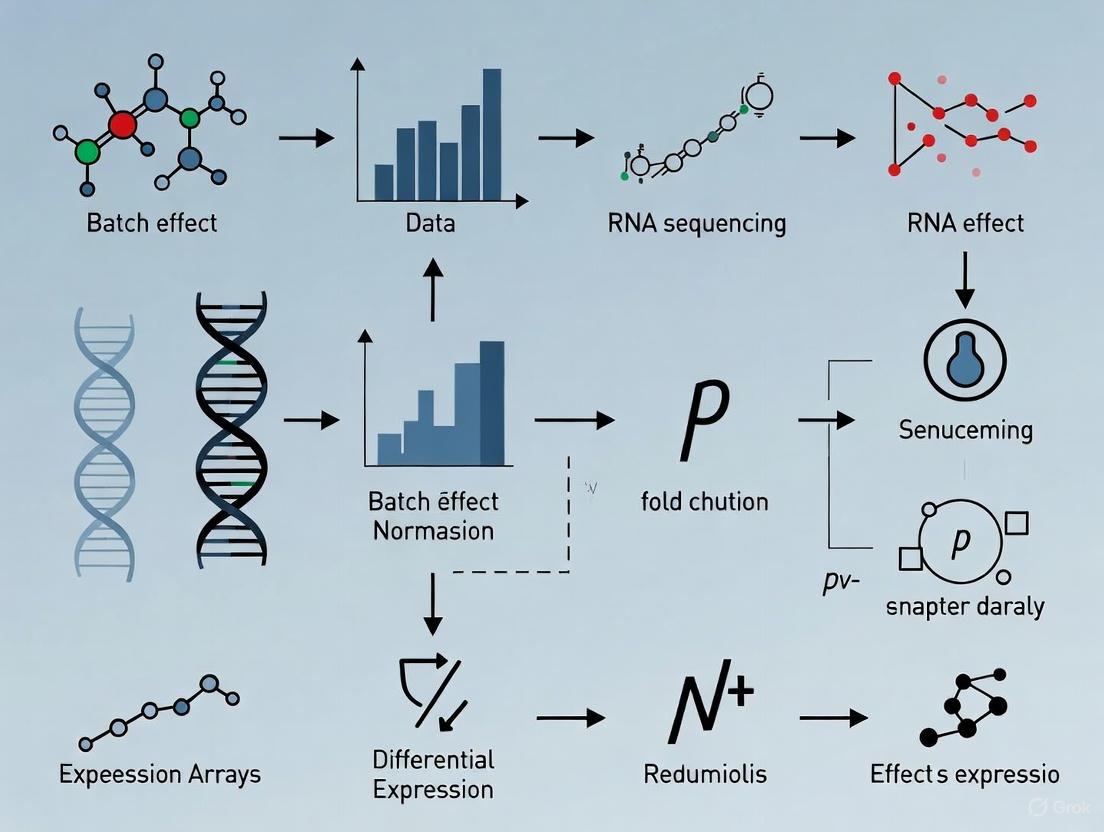

The diagram below illustrates this diagnostic workflow.

Guide 2: Correcting Batch Effects in scRNA-seq Data

For single-cell data, specific methods are required to handle its unique characteristics.

- Objective: To integrate multiple batches of scRNA-seq data, removing technical variation while preserving biological heterogeneity.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Preprocessing: Normalize your raw count data and identify highly variable genes using a standard scRNA-seq pipeline (e.g., in Seurat or Scanpy).

- Method Selection: Choose a batch correction method designed for single-cell data. Based on comprehensive benchmarks, the most effective methods are [3]:

- Harmony: Fast and effective, uses iterative clustering to remove batch effects.

- Seurat Integration: Uses Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and mutual nearest neighbors (MNNs) to find "anchors" between datasets.

- LIGER: Uses integrative non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to distinguish shared and dataset-specific factors.

- Application: Run the chosen method following its specific tutorial and documentation.

- Validation: Visualize the integrated data using UMAP or t-SNE. After successful correction, cells of the same type from different batches should mix together, while distinct cell types should remain separate.

The following workflow outlines the key steps for single-cell data integration.

Performance Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Algorithms

The table below summarizes the performance of top-performing methods from a large-scale benchmark of scRNA-seq data [3]. Harmony, Seurat 3, and LIGER are generally recommended, with Harmony often favored for its computational speed.

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Runtime | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony [3] | Iterative clustering in PCA space | General use, large datasets | Fastest | Low-dimensional embedding |

| Seurat 3 [6] [3] | CCA and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) | Identifying shared cell types across batches | Moderate | Corrected expression matrix |

| LIGER [3] | Integrative Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) | Distinguishing technical from biological variation | Moderate | Factorized matrices |

| ComBat-seq [5] [7] | Empirical Bayes model | Bulk or single-cell RNA-seq count data | Fast | Corrected count matrix |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details common reagents and materials that are frequent sources of batch effects, emphasizing the need for careful tracking and, where possible, standardization.

| Item | Function | Batch Effect Risk & Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) [2] | Provides nutrients and growth factors for cell culture. | High risk. Bioactive components can vary significantly between lots, affecting cell growth and gene expression. Mitigation: Test new lots for performance; use a single lot for an entire study. |

| RNA-Extraction Kits [2] | Isolate and purify RNA from samples. | High risk. Changes in reagent composition or protocol can alter yield and quality. Mitigation: Use the same kit and lot number; if a change is unavoidable, process samples from all groups with both lots to account for the effect. |

| Sequencing Kits & Flow Cells [6] | Prepare libraries and perform sequencing. | High risk. Different lots can have varying efficiencies, leading to batch-specific biases in sequencing depth and quality. Mitigation: Multiplex samples from different biological groups across all sequencing runs. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Reverse Transcriptase) [6] | Converts RNA to cDNA in RNA-seq workflows. | Moderate risk. Variations in enzyme efficiency can affect amplification and library complexity. Mitigation: Use the same reagent batch for a related set of experiments. |

Special Considerations and Limitations

- Unbalanced Designs: Batch effect correction methods can produce misleading results and introduce false positives if your experimental design is unbalanced (e.g., all control samples were processed in one batch and all disease samples in another) [4]. Always aim for a balanced design.

- Over-Correction: Aggressive batch correction can inadvertently remove biologically meaningful signal, especially if there are unknown biological subgroups that are confounded with batch [1] [4]. It is crucial to validate that known biological differences are preserved after correction.

This guide is part of a broader thesis on ensuring data reproducibility in genomic research.

Batch effects are technical variations introduced during experimental processes that are unrelated to the biological signals of interest. They represent a significant challenge in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, potentially leading to misleading outcomes, irreproducible results, and invalidated research findings [8] [2]. This technical support center article details the common sources of batch effects and provides actionable troubleshooting guidance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Batch effects can arise at virtually every stage of a high-throughput study, from initial study design to final data generation [8]. The table below summarizes the most frequently encountered sources of technical variation.

Table 1: Common Sources of Batch Effects in Omics Studies

| Source Category | Specific Examples | Affected Omics Types |

|---|---|---|

| Reagents & Kits | Different lots of RNA-extraction solutions, fetal bovine serum (FBS), enzyme batches for cell dissociation, and reagent quality [8] [9] [2]. | Common to all (Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics) |

| Instruments & Platforms | Different sequencing machines (e.g., Illumina vs. Ion Torrent), mass spectrometers, laboratory equipment, and changes in hardware calibration [9] [10]. | Common to all |

| Personnel & Protocols | Variations in techniques between different handlers or technicians, differences in sample processing protocols, and deviations in standard operating procedures [10] [5]. | Common to all |

| Lab Conditions | Fluctuations in ambient temperature during cell capture, humidity, ozone levels, and sample storage conditions (e.g., temperature, duration, freeze-thaw cycles) [9] [10]. | Common to all |

| Sample Preparation & Storage | Variables in sample collection, centrifugal forces during plasma separation, time and temperatures prior to centrifugation, and storage duration [8] [2]. | Common to all |

| Sequencing Runs | Processing samples across different days, weeks, or months; different sequencing lanes or flow cells; and variations in PCR amplification efficiency [6] [10]. | Common to all, especially Transcriptomics |

| Flawed Study Design | Non-randomized sample collection, processing batches highly correlated with biological outcomes, and imbalanced cell types across samples [8] [11] [2]. | Common to all |

The following diagram illustrates how these sources introduce variation throughout a typical experimental workflow.

Figure 1: Potential points of batch effect introduction in a high-throughput omics workflow.

How can I detect batch effects in my data?

Before applying corrective measures, it is crucial to assess whether your data suffers from batch effects. Both visual and quantitative methods are available.

Visual Assessment Methods

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on your raw data and color the data points by batch. If the top principal components show clear separation of samples by batch rather than by biological condition, this indicates strong batch effects [11] [12] [5].

- t-SNE or UMAP Plots: Visualize your data using t-SNE or UMAP and overlay the batch labels. In the presence of batch effects, cells or samples from different batches will form distinct clusters instead of mixing based on biological similarity (e.g., cell type or disease condition) [11] [12].

- Clustering and Heatmaps: Generate hierarchical clustering dendrograms or heatmaps of your data. If samples cluster primarily by batch instead of by treatment group, it signals a batch effect [11].

Quantitative Metrics

For a less biased assessment, several quantitative metrics can be employed. These are particularly useful for benchmarking the success of batch correction methods.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Batch Effects

| Metric Name | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| kBET (k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test) | Tests whether the local neighborhood of a cell matches the global batch composition [9] [13]. | A rejection of the null hypothesis indicates poor local batch mixing. |

| LISI (Local Inverse Simpson's Index) | Measures both batch mixing (Batch LISI) and cell type separation (Cell Type LISI) [9]. | A higher Batch LISI indicates better batch mixing. A higher Cell Type LISI indicates better biological signal preservation. |

| ARI (Adjusted Rand Index) | Measures the similarity between two clusterings (e.g., before and after correction) [12]. | Values closer to 1 indicate better preservation of clustering structure. |

| NMI (Normalized Mutual Information) | Measures the mutual dependence between clustering outcomes and batch labels [12]. | Lower values indicate less dependence on batch, suggesting successful correction. |

| PCR_batch | Percentage of corrected random pairs within batches [12]. | Aids in evaluating the integration of cells from different samples. |

What is the difference between normalization and batch effect correction?

Researchers often confuse these two distinct preprocessing steps. The table below clarifies their different objectives and operational scales.

Table 3: Normalization vs. Batch Effect Correction

| Aspect | Normalization | Batch Effect Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Adjusts for cell-specific technical biases to make expression counts comparable across cells. | Removes technical variations that are systematically associated with different batches of experiments. |

| Technical Variations Addressed | Sequencing depth (library size), RNA capture efficiency, amplification bias, and gene length [12] [9]. | Different sequencing platforms, processing times, reagent lots, personnel, and laboratory conditions [12]. |

| Typical Input | Raw count matrix (cells x genes) [12]. | Often uses normalized (and sometimes dimensionally-reduced) data, though some methods correct the full expression matrix [12]. |

| Examples | Log normalization, SCTransform, Scran's pooling-based normalization, CLR [9]. | Harmony, Seurat Integration, ComBat, MNN Correct, LIGER [6] [11] [12]. |

The following workflow chart demonstrates how these processes fit into a typical single-cell RNA-seq analysis pipeline.

Figure 2: Placement of normalization and batch effect correction in a standard scRNA-seq analysis workflow.

How do I choose an appropriate batch effect correction method?

Selecting a suitable method depends on your data type, size, and the nature of the biological question. There is no one-size-fits-all solution [8].

Table 4: Commonly Used Batch Effect Correction Methods for Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Method | Underlying Algorithm | Input Data | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony [6] [12] [9] | Iterative clustering and linear correction in PCA space. | Normalized count matrix. | Fast, scalable, preserves biological variation well [9] [14]. | Limited native visualization tools [9]. |

| Seurat Integration [6] [12] [9] | Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN). | Normalized count matrix. | High biological fidelity, integrates with Seurat's comprehensive toolkit [9]. | Computationally intensive for large datasets [9]. |

| BBKNN [9] | Batch Balanced K-Nearest Neighbors. | k-NN graph. | Computationally efficient, lightweight [9]. | Less effective for complex non-linear batch effects; parameter sensitive [9]. |

| scANVI [9] | Deep generative model (variational autoencoder). | Raw or normalized counts. | Handles complex batch effects; can incorporate cell labels. | Requires GPU; demands technical expertise [9]. |

| ComBat/ComBat-seq [14] [5] | Empirical Bayes framework. | Raw count matrix (ComBat-seq) or normalized data (ComBat). | Established method; good for bulk or single-cell RNA-seq. | Can introduce artifacts; assumptions of linear batch effects [14]. |

| MNN Correct [12] | Mutual Nearest Neighbors. | Normalized count matrix. | Does not require identical cell type compositions. | Computationally demanding; can alter data considerably [12] [14]. |

| LIGER [6] [12] | Integrative non-negative matrix factorization (NMF). | Normalized count matrix. | Effective for large, complex datasets. | Can be aggressive, potentially removing biological signal [14]. |

Practical Correction Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol, adaptable in tools like R or Python, outlines a typical batch correction process using a popular method.

Protocol: Batch Effect Correction using Harmony on scRNA-seq Data

Objective: To integrate multiple single-cell RNA-seq datasets and remove technical batch effects while preserving biological heterogeneity.

Software Requirements: R programming environment, Harmony library, and single-cell analysis toolkit (e.g., Seurat).

Data Preprocessing and Normalization:

- Load your raw count matrices and metadata (containing batch information) into your analysis environment.

- Normalize the data to account for differences in sequencing depth. A common method is log-normalization.

- Select Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) to focus the analysis on genes containing the most biological signal.

- Scale the data and perform principal component analysis (PCA) to obtain a low-dimensional representation.

Assess Batch Effects:

- Visualize the PCA results, coloring cells by their batch of origin. Observe if batches form separate clusters.

- Optionally, compute quantitative metrics like kBET or LISI on the pre-correction PCA embedding to establish a baseline.

Run Harmony Integration:

- Use the

RunHarmonyfunction, providing the PCA embedding and the batch variable (e.g.,batch_var = "processing_date"). - Harmony will iteratively cluster cells and correct the PCA embeddings, returning a new, batch-corrected embedding.

- Use the

Post-Correction Analysis and Validation:

- Use the corrected Harmony embedding to build a k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) graph and perform clustering and UMAP visualization.

- Validate the correction:

- Color the new UMAP by batch. Batches should be well-mixed within biological clusters.

- Color the UMAP by cell type. Distinct cell types should remain separate, confirming biological signals were preserved.

- Be vigilant for signs of over-correction, such as distinct cell types being forced together or a complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions [11].

What are the signs of over-correction and how can I avoid it?

Over-correction occurs when a batch effect correction method removes not only technical variation but also genuine biological signal. This can be as detrimental as not correcting at all.

Key Signs of Over-Correction:

- Loss of Biological Distinction: Distinct cell types are clustered together on dimensionality reduction plots (UMAP, t-SNE) when they should be separate [11] [12].

- Unrealistic Overlap: A complete overlap of samples originating from very different biological conditions or experiments, especially when minor differences are central to the experimental design [11].

- Compromised Marker Genes: A significant portion of cluster-specific markers are composed of genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) instead of canonical cell-type-specific markers. There may also be a notable absence of expected differential expression hits [11] [12].

Strategies to Avoid Over-Correction:

- Benchmark Methods: Test multiple batch correction methods on your data. Begin with methods known for good performance, such as Harmony, which has been recommended for being well-calibrated and introducing fewer artifacts [14].

- Use Quantitative Metrics: Employ metrics like LISI that measure both batch mixing (iLISI) and cell type separation (cLISI). A good correction should increase iLISI (better batch mixing) without significantly decreasing cLISI (preserved biological separation) [9].

- Iterative Evaluation: Always compare pre- and post-correction visualizations and metrics. Be critical of results that show perfect mixing at the expense of known biological structure.

Table 5: Essential Experimental and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Batch Effect Management |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Protocols | Detailed, written procedures for sample processing. | Minimizes personnel-induced variation and ensures consistency across experiments and time [6]. |

| Single Reagent Lot | Using the same manufacturing batch of key reagents (e.g., FBS, enzymes) for an entire study. | Prevents a major source of technical variation [8] [6]. |

| Sample Multiplexing | Processing multiple samples together in a single sequencing run using cell hashing or similar techniques. | Reduces confounding of batch and sample identity [11]. |

| Reference Samples | Including control or reference samples in every processing batch. | Provides a technical baseline to monitor and correct for inter-batch variation. |

| Harmony | Computational batch correction tool. | A robust and widely recommended method for integrating single-cell data with minimal artifacts [6] [9] [14]. |

| Seurat | Comprehensive single-cell analysis suite. | Provides a full workflow, including its own high-fidelity integration method [6] [9]. |

| Scanpy | Python-based single-cell analysis toolkit. | Offers multiple integrated batch correction methods like BBKNN and Scanorama [9]. |

| Polly | Data management and processing platform. | Automates batch effect correction and provides "Polly Verified" reports to ensure data quality [12]. |

In the era of large-scale biological data, batch effects represent a fundamental challenge that can compromise the utility of high-throughput genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets. Batch effects are technical variations introduced into data due to differences in experimental conditions, processing times, personnel, reagent lots, or measurement technologies [15] [2]. These non-biological variations create structured patterns of distortion that permeate all replicates within a processing batch and vary markedly between batches [16]. The consequences range from reduced statistical power to completely misleading findings when batch effects confound true biological signals [2] [16]. This technical support article examines the profound implications of uncorrected batch effects and provides practical guidance for researchers navigating this complex analytical challenge.

FAQ: Understanding Batch Effects

What exactly are batch effects and how do they arise?

Batch effects are technical variations in data that are unrelated to the biological questions under investigation. They arise from differences in experimental conditions across multiple aspects of data generation [2]:

- Sample processing: Variations in personnel, protocols, reagent lots, or equipment across different laboratories or processing days

- Technical platforms: Different sequencing technologies, microarray platforms, or measurement instruments

- Temporal factors: Data collected at different times, even within the same laboratory

- Sample storage: Differences in how samples are collected, prepared, and stored before analysis

The fundamental cause can be partially attributed to fluctuations in the relationship between the actual biological abundance of an analyte and its measured intensity across different experimental conditions [2].

Why are batch effects particularly problematic in genomic studies?

Batch effects have profound negative impacts on genomic studies because they can:

- Reduce statistical power by introducing extra variation that dilutes true biological signals [2] [16]

- Generate false positives when batch effects correlate with outcomes of interest, leading to incorrect conclusions [2]

- Hinder reproducibility across studies and laboratories, potentially resulting in retracted articles and invalidated findings [2]

- Complicate data integration from multiple sources, limiting the value of consortium efforts and meta-analyses [17]

In one documented case, a change in RNA-extraction solution caused a shift in gene-based risk calculations, resulting in incorrect classification for 162 patients, 28 of whom received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy regimens [2].

How can I determine if my data has batch effects?

Several approaches can help identify batch effects in your data:

Table 1: Methods for Batch Effect Detection

| Method | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| PCA Visualization | Perform PCA on raw data and color points by batch | Separation of samples by batch in top principal components suggests batch effects |

| t-SNE/UMAP Plots | Project data using t-SNE or UMAP and overlay batch labels | Clustering of samples by batch rather than biological factors indicates batch effects |

| Clustering Analysis | Examine dendrograms or heatmaps of samples | Samples clustering by processing batch rather than treatment group signals batch effects |

| Quantitative Metrics | Use metrics like kBET, LISI, or ASW | Statistical measures of batch mixing that reduce human bias in assessment [11] |

What are the signs that I may have over-corrected batch effects?

Over-correction occurs when batch effect removal also eliminates genuine biological signals. Warning signs include [11]:

- Distinct cell types clustering together on dimensionality reduction plots (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP)

- Complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions or experiments

- Cluster-specific markers comprised mainly of genes with widespread high expression across cell types (e.g., ribosomal genes)

- Loss of expected biological variation that should differentiate sample groups

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Batch Effect Scenarios

Scenario 1: Fully Confounded Study Design

Problem: In a fully confounded design, biological groups completely separate by batches (e.g., all controls in one batch, all cases in another), making it impossible to distinguish biological effects from batch effects [15].

Solutions:

- Remeasurement strategy: If possible, remeasure a subset of samples across batches. Research shows that when between-batch correlation is high, remeasuring even a small subset can rescue most statistical power [18].

- Statistical approaches: Methods like "ReMeasure" specifically address highly confounded case-control studies by leveraging remeasured samples in the maximum likelihood framework [18].

- Prevention: Always design studies with balanced distribution of biological groups across batches when possible.

Scenario 2: Choosing an Inappropriate Correction Method

Problem: Different batch effect correction methods have varying assumptions and performance characteristics. Selecting an inappropriate method can lead to poor correction or over-correction.

Solutions:

- Method benchmarking: Consult comprehensive benchmarking studies that evaluate multiple methods across various data types and scenarios [3] [17].

- Data-type consideration: Choose methods appropriate for your data type and distribution:

- Multiple testing: Try several methods and compare results to ensure robustness.

Scenario 3: Sample Imbalance Across Batches

Problem: Differences in cell type numbers, cell counts per type, and cell type proportions across samples (common in cancer biology) can substantially impact integration results and biological interpretation [11].

Solutions:

- Acknowledge limitations: Recognize that most batch correction methods assume similar cell type compositions across batches.

- Specialized approaches: Consider methods like LIGER, which aims to remove only technical variations while preserving biological differences between batches [3].

- Guidance adherence: Follow refined guidelines for data integration in imbalanced settings, as proposed by Maan et al. (2024) [11].

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Management

Protocol 1: Batch Effect Assessment Workflow

- Data Preparation: Begin with raw, unnormalized data from all batches.

- Initial Visualization: Perform PCA and color points by batch identity and biological groups.

- Cluster Analysis: Generate heatmaps and dendrograms to examine sample clustering patterns.

- Quantitative Assessment: Apply metrics like kBET or LISI for objective batch effect quantification.

- Document Findings: Record the extent and nature of batch effects before proceeding with correction.

Figure 1: Batch effect assessment workflow for identifying technical variations in omics data

Protocol 2: Comparative Evaluation of Batch Correction Methods

- Select Multiple Methods: Choose 3-4 methods representing different approaches (e.g., Harmony, Seurat, ComBat).

- Apply Corrections: Implement each method following author recommendations and default parameters.

- Visual Evaluation: Generate UMAP/t-SNE plots of corrected data colored by batch and cell type.

- Quantitative Evaluation: Calculate batch mixing metrics (kBET, LISI) and biological preservation metrics (ASW, ARI).

- Method Selection: Choose the method that best balances batch removal with biological signal preservation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Batch Effect Correction Methods

Computational Correction Tools

Table 2: Batch Effect Correction Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Approach | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony | Mixture model-based integration | Single-cell RNA-seq, image-based profiling | Fast runtime, good performance across scenarios [17] [3] |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes, location-scale adjustment | Microarray, bulk RNA-seq data | Assumes Gaussian distribution after transformation [19] [16] |

| Seurat | CCA or RPCA with mutual nearest neighbors | Single-cell RNA-seq data | Multiple integration options (CCA, RPCA) with different strengths [17] |

| LIGER | Integrative non-negative matrix factorization | Datasets with biological differences between batches | Preserves biological variation while removing technical effects [3] |

| Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) | Nearest neighbor matching across batches | Single-cell RNA-seq | Pioneering approach for single-cell data; basis for several other methods [3] |

| scVI | Variational autoencoder | Large, complex single-cell datasets | Neural network approach; requires substantial computational resources [17] |

Experimental Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagents and Materials for Batch Effect Mitigation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Batch Effect Control | Implementation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Normalization across batches and platforms | Include identical reference samples in each batch to quantify technical variation |

| Control Samples | Assessment of technical variability | Process positive and negative controls in each batch to monitor performance |

| Standardized Reagent Lots | Reduce batch-to-batch variation | Use the same reagent lots for all samples in a study when possible |

| Sample Multiplexing Kits | Internal batch effect control | Label samples with barcodes and process together to minimize technical variation |

Advanced Topics in Batch Effect Correction

Batch Effects in Emerging Technologies

As new technologies evolve, they present unique batch effect challenges:

Single-cell RNA sequencing: scRNA-seq data suffers from higher technical variations than bulk RNA-seq, including lower RNA input, higher dropout rates, and greater cell-to-cell variation, making batch effects more severe [2].

Image-based profiling: Technologies like Cell Painting, which extracts morphological features from cellular images, face batch effects from different microscopes, staining concentrations, and cell growth conditions across laboratories [17] [20].

Multi-omics integration: Combining data from different omics layers (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) introduces additional complexity as each data type has different distributions, scales, and batch effect characteristics [2].

The Role of Experimental Design in Batch Effect Prevention

Proper experimental design remains the most effective strategy for managing batch effects:

- Balance and randomization: Distribute biological groups of interest equally across all processing batches [15] [16]

- Batch recording: Meticulously document all potential batch variables (processing date, personnel, reagent lots, instrument ID)

- Reference samples: Include technical replicates and reference materials in each batch to facilitate downstream correction

- Block designs: Structure experiments so that biological comparisons of interest are made within rather than between batches

Figure 2: Experimental design strategies to prevent batch effects and ensure valid biological conclusions

Batch effects represent a fundamental challenge in modern biological research that cannot be ignored or easily eliminated. The consequences of uncorrected batches range from reduced statistical power to completely misleading biological conclusions, with potentially serious implications for both basic research and clinical applications. Successful navigation of this landscape requires a multi-faceted approach: vigilant experimental design to minimize batch effects at source, comprehensive assessment to quantify their impact, appropriate correction methods tailored to specific data types and research questions, and careful evaluation to avoid over-correction that removes biological signal along with technical noise. As technologies evolve and datasets grow in size and complexity, continued development and benchmarking of batch effect correction methods will remain essential for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of biological findings.

A technical support guide for genomic researchers

What are batch effects and why is detecting them crucial?

In transcriptomics, a batch effect refers to systematic, non-biological variation introduced into gene expression data by technical inconsistencies. These can arise from differences in sample collection, library preparation, sequencing machines, reagent lots, or personnel [21].

If undetected, these technical variations can obscure true biological signals, leading to misleading conclusions, false positives in differential expression analysis, or missed discoveries [21]. Visual diagnostic tools like PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP provide a first and intuitive way to detect these unwanted patterns.

How do I use PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP to spot batch effects?

The core principle is simple: in the presence of a strong batch effect, cells or samples will cluster by their technical batch rather than by their biological identity (e.g., cell type or treatment condition) [11].

The table below summarizes the standard approach for each method.

| Method | How to Perform Detection | What Indicates a Batch Effect? |

|---|---|---|

| PCA | Perform PCA on raw data and create scatter plots of the top principal components (e.g., PC1 vs. PC2) [11]. | Data points separate into distinct groups based on batch identity along one or more principal components [11]. |

| t-SNE / UMAP | Generate t-SNE or UMAP plots and color the data points by their batch of origin [11]. | Clear separation of batches into distinct, non-overlapping clusters on the 2D plot [21] [11]. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for visual diagnosis and subsequent correction of batch effects.

My data shows batch effects. What correction method should I use?

Several statistical and machine learning methods have been developed to correct for batch effects. The choice of method can depend on your data type (e.g., bulk vs. single-cell RNA-seq) and the complexity of the batch effect.

Recent independent benchmarking studies have compared the performance of various methods. The following table summarizes findings from a 2025 study that compared eight widely used methods for single-cell RNA-seq data [22].

| Method | Reported Performance | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Harmony | Consistently performed well in all tests; only method recommended by the study [22]. | Often noted for fast runtime in other benchmarks [11]. |

| ComBat | Introduced measurable artifacts in the test setup [22]. | Uses an empirical Bayes framework; widely used but requires known batch info [21]. |

| ComBat-Seq | Introduced measurable artifacts in the test setup [22]. | Variant for RNA-Seq raw count data [23]. |

| Seurat | Introduced measurable artifacts in the test setup [22]. | Often used in single-cell analyses; earlier versions used CCA, later versions use MNNs [24]. |

| BBKNN | Introduced measurable artifacts in the test setup [22]. | A fast method that works by creating a batch-balanced k-nearest neighbour graph [25]. |

| MNN | Performed poorly, often altering data considerably [22]. | Mutual Nearest Neighbors; a foundational algorithm used by other tools [24]. |

| SCVI | Performed poorly, often altering data considerably [22]. | A neural network-based approach (Variational Autoencoder) [24]. |

| LIGER | Performed poorly, often altering data considerably [22]. | Based on integrative non-negative matrix factorization [11]. |

Note: Another large-scale benchmark (Luecken et al., 2022) suggested that scANVI (a neural network-based method) performs best, while Harmony is a good but less scalable option [11]. It is advisable to test a few methods on your specific dataset.

How can I be sure I haven't over-corrected and removed biology?

Over-correction is a valid concern, where the correction method removes true biological variation along with the technical noise [21]. Watch for these indicative signs:

- Distinct Cell Types Merge: After correction, previously separate cell types are clustered together on your UMAP/t-SNE plot [11].

- Implausible Overlap: A complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions (e.g., healthy and diseased) where some differences are expected [11].

- Non-informative Markers: Cluster-specific markers identified after correction are dominated by genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) instead of biologically meaningful markers [11].

If you suspect over-correction, try a less aggressive correction method or adjust its parameters.

A Researcher's Toolkit: Key Metrics for Quantifying Batch Effects

While visual tools are essential for a first pass, quantitative metrics provide an objective assessment of batch effect strength and correction quality. The table below lists key metrics used in the field [26] [21] [24].

| Metric Name | Type | What It Measures | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Silhouette Width (ASW) | Cell type-specific | How well clusters are separated and cohesive. Higher values indicate better-defined clusters [26] [21]. | Values close to 1 indicate tight, well-separated clusters. Batch effects reduce ASW [21]. |

| k-Nearest Neighbour Batch Effect Test (kBET) | Cell type-specific / Cell-specific | Tests if batch proportions in a cell's neighbourhood match the global proportions [26] [21]. | A high acceptance rate indicates good batch mixing within cell types [21] [24]. |

| Local Inverse Simpson's Index (LISI) | Cell-specific | The effective number of batches in a cell's neighbourhood [26] [21]. | Higher LISI scores indicate better mixing, with an ideal score equal to the number of batches [21]. |

| Cell-specific Mixing Score (cms) | Cell-specific | Tests if distance distributions in a cell's neighbourhood are batch-specific [26]. | A p-value indicating the probability of observed differences assuming no batch effect. Lower p-values suggest local batch bias [26]. |

| Graph Connectivity (GC) | Cell type-specific | The fraction of cells that remain connected in a graph after batch correction [24]. | Higher values (closer to 1) indicate better preservation of biological group structure [24]. |

Essential Materials and Reagents for scRNA-seq Batch Effect Investigation

The following table details key reagents and computational tools frequently mentioned in batch effect research.

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Harmony | A robust batch correction algorithm that uses PCA and iterative clustering to integrate data across batches [22] [24]. |

| Seurat | A comprehensive R toolkit for single-cell genomics, which includes data integration functions [22] [24]. |

| CellMixS | An R/Bioconductor package that provides the cell-specific mixing score (cms) to quantify and visualize batch effects [26]. |

| BBKNN | A batch effect removal tool that quickly computes a batch-balanced k-nearest neighbour graph [25]. |

| scGen / FedscGen | A neural network-based method (VAE) for batch correction. FedscGen is a privacy-preserving, federated version [24]. |

| pyComBat | A Python implementation of the empirical Bayes methods ComBat and ComBat-Seq for correcting batch effects [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Visual Batch Effect Diagnosis

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for detecting batch effects using visual tools, as commonly implemented in tools like Scanpy or Seurat.

Objective: To visually assess the presence of technical batch effects in a single-cell RNA sequencing dataset.

Materials:

- A compiled single-cell dataset (e.g., an AnnData object in Scanpy or a Seurat object) containing cells from multiple batches.

- Bioinformatics environment with Python (Scanpy, NumPy) or R (Seurat) installed.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Perform standard preprocessing on your raw count matrix. This typically includes quality control filtering, normalization, and log-transformation. Identify highly variable genes.

- Dimensionality Reduction (PCA):

- Scale the data to unit variance and zero mean.

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the scaled data of highly variable genes.

- Visualization: Create a scatter plot of the first two principal components (PC1 vs. PC2). Color the data points by their batch identifier (e.g., sequencing run, donor).

- Interpretation: Observe if points cluster strongly by batch. Proceed to the next step regardless.

- Non-Linear Embedding (UMAP/t-SNE):

- Construct a k-nearest neighbour (k-NN) graph based on the top principal components (e.g., first 20-50 PCs).

- Generate a UMAP (or t-SNE) plot from this k-NN graph.

- Visualization: Create the UMAP plot and color the data points by batch. Generate a second UMAP plot colored by cell type or biological condition.

- Interpretation: Compare the two plots. In the "batch" plot, check for strong, separate clusters based on batch. In the "cell type" plot, check if the same cell type from different batches forms separate clusters instead of mixing together.

- Documentation and Decision:

- Save all plots.

- If visual inspection reveals strong batch clustering, proceed to batch correction using a method of choice (see FAQ above). After correction, always repeat steps 2 and 3 to validate that the batch effect has been reduced and biological structures are preserved.

This workflow is encapsulated in the following diagram, which also includes the iterative validation step after correction.

What are the primary formal statistical tests for batch effect detection?

Several formal statistical tests exist to diagnose batch effects, moving beyond visual inspection of PCA plots. The table below summarizes the key methods:

| Method Name | Underlying Principle | Key Metric | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| findBATCH [27] | Probabilistic Principal Component and Covariates Analysis (PPCCA) | 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for batch effect on each probabilistic PC | pPCs with 95% CIs not including zero have a significant batch effect |

| Guided PCA (gPCA) [28] | Guided Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) using a batch indicator matrix | δ statistic (proportion of variance due to batch) | δ near 1 implies a large batch effect; significance is assessed via permutation testing (p-value) |

| Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) [27] [29] | Hybrid approach combining PCA and variance components analysis | Proportion of variance explained by the batch factor | A higher proportion indicates a greater influence of batch effects on the data |

Can you provide a protocol for implementing the findBATCH and gPCA tests?

Experimental Protocol: Statistical Testing for Batch Effects

A. Implementation of findBATCH using the exploBATCH R Package

- Data Pre-processing and Normalization: Independently pre-process and normalize each individual dataset according to the technology used (e.g., microarray, RNA-seq). [27]

- Data Pooling: Pool the processed datasets based on common identifiers, such as gene names or probes. [27]

- Optimal Component Selection: Run the

findBATCHfunction. It will first select the optimal number of probabilistic Principal Components (pPCs) based on the highest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) value. These pPCs explain the majority of the data variability. [27] - Statistical Testing and Visualization: The function computes the estimated batch effect (as a regression coefficient) and its 95% Confidence Interval for each pPC. Results are typically displayed in a forest plot. [27]

- Interpretation: Identify pPCs where the 95% CI for the batch effect does not include zero. These are the components significantly associated with batch effects. [27]

B. Implementation of Guided PCA (gPCA) using the gPCA R Package

- Batch Indicator Matrix: Create a batch indicator matrix (

Y) where rows represent samples and columns represent different batches. [28] - Perform gPCA: Conduct a guided PCA on the matrix

X'Y, whereXis your centered genomic data matrix (e.g., gene expression). This guides the analysis to find directions of variation associated with the predefined batches. [28] - Calculate the δ Statistic: Compute the test statistic

δ, which is the ratio of the variance explained by the first principal component from gPCA to the variance explained by the first principal component from traditional, unguided PCA. [28]δ = (Variance of PC1 from gPCA) / (Variance of PC1 from unguided PCA) - Permutation Test for Significance:

- Permute the batch labels of the samples (e.g., 1000 times).

- For each permutation, recalculate the δ statistic (

δ_p). - The p-value is the proportion of permuted

δ_pvalues that are greater than or equal to the observed δ value from the original data. [28]

- Interpretation: A significant p-value (e.g., < 0.05) indicates the presence of a statistically significant batch effect in the data. [28]

What are the common metrics for evaluating batch effect correction performance?

After applying a batch correction method, its performance can be quantitatively evaluated using the following sample-based and feature-based metrics:

| Metric Category | Metric Name | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample-Based Metrics | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) [29] | Evaluates the resolution in differentiating known biological groups (e.g., using PCA). Higher SNR indicates better preservation of biological signal. | Used when sample group labels are known. |

| Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) [29] | Quantifies the proportion of total variance in the data explained by biological factors versus batch factors. A successful correction reduces the variance component for batch. | General purpose for partitioned variance. | |

| Feature-Based Metrics | Coefficient of Variation (CV) [29] | Measures the variability of a feature (e.g., a gene) across technical replicates within and between batches. Lower CV after correction indicates improved precision. | Requires technical replicates. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) & Pearson Correlation (RC) [29] | Assess the accuracy of identifying Differentially Expressed Genes/Proteins (DEGs/DEPs). MCC is more robust for unbalanced designs. Used with simulated data where the "truth" is known. | Benchmarking with simulated data. |

What statistical pitfalls should I be aware of during batch correction?

A major consideration is the choice between a one-step and a two-step correction process, which can significantly impact downstream statistical inference. [30]

- One-Step Correction: Batch variables are included directly in the statistical model during the primary analysis (e.g., differential expression). This is statistically sound but can be inflexible for complex downstream analyses. [30]

- Two-Step Correction: Batch effects are removed in a preprocessing step, and the "cleaned" data is used for all downstream analyses. While popular and flexible, this approach has a critical pitfall: the correction process introduces a correlation structure between samples within the same batch. [30]

- The Problem: If this induced correlation is ignored in downstream analyses (e.g., by using a standard linear model that assumes independent samples), it can lead to either exaggerated significance (increased false positives) or diminished significance (loss of power). This is especially problematic in unbalanced designs where biological groups are not uniformly distributed across batches. [30]

- The Solution: If using a two-step method like ComBat, one proposed solution is to use the ComBat+Cor approach. This involves estimating the sample correlation matrix of the batch-corrected data and incorporating it into the downstream model using Generalized Least Squares (GLS) to account for the dependencies. [30]

| Item / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | The primary environment for implementing most statistical batch effect tests and corrections. [27] [28] |

exploBATCH R Package |

Provides the implementation for the findBATCH (detection) and correctBATCH (correction) methods based on PPCCA. [27] |

gPCA R Package |

Provides functionality to perform guided PCA and the associated statistical test for batch effects. [28] |

sva / ComBat-seq R Package |

Contains the ComBat and ComBat-seq algorithms for two-step batch effect correction, widely used as a standard. [31] [7] |

| Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet Project) | Well-characterized control samples (like the Quartet protein reference materials) profiled across multiple batches and labs to benchmark and evaluate batch effect correction methods. [29] |

| Simulated Data with Known Truth | Datasets with built-in batch effects and known differential expression patterns, used for controlled method validation and calculation of metrics like MCC. [29] |

A Methodologist's Toolkit: Choosing and Applying the Right Correction Algorithm

The integration of large-scale genomics data has become fundamental to modern biological research and drug development. However, this integration is routinely hindered by unwanted technical variations known as batch effects—systematic differences between datasets generated under different experimental conditions, times, or platforms [32]. These effects can obscure true biological signals, reduce statistical power, and potentially lead to false positive findings if not properly addressed [33] [34].

The Empirical Bayes framework ComBat has emerged as a powerful approach for correcting these technical artifacts. Originally developed for microarray gene expression data, ComBat estimates and removes additive and multiplicative batch effects using an empirical Bayes approach that effectively borrows information across features [35]. This method has seen widespread adoption across genomic technologies due to its ability to handle small sample sizes while avoiding over-correction.

More recently, the field has witnessed the development of ComBat-met, a specialized extension designed to address the unique characteristics of DNA methylation data [32]. Unlike other genomic data types, DNA methylation is quantified as β-values (methylation percentages) constrained between 0 and 1, often exhibiting skewness and over-dispersion that violate the normality assumptions of standard ComBat [32] [34]. ComBat-met employs a beta regression framework specifically tailored to these distributional properties, representing a significant evolution in the ComBat methodology for epigenomic applications.

ComBat-met: Technical Framework and Implementation

Core Methodology

ComBat-met addresses the fundamental limitation of standard ComBat when applied to DNA methylation data. Traditional ComBat assumes normally distributed data, making it suboptimal for β-values that are proportion measurements bounded between 0 and 1 [32]. The ComBat-met framework introduces several key innovations:

Beta Regression Model: Instead of using normal distribution assumptions, ComBat-met models β-values using a beta distribution parameterized by mean (μ) and precision (φ) parameters [32]. This better captures the characteristic distribution of methylation data.

Quantile-Matching Adjustment: The adjustment procedure calculates batch-free distributions and maps the quantiles of the estimated distributions to their batch-free counterparts [32]. This non-parametric approach preserves the distributional properties of the corrected data.

Reference-Based Option: Unlike the standard ComBat which typically aligns batches to an overall mean, ComBat-met provides the option to adjust all batches to a designated reference batch, preserving the technical characteristics of a specific dataset [32].

The method can be represented by the following statistical model:

Let ( y_{ij} ) denote the β-value of a feature in sample ( j ) from batch ( i ). The beta regression model is defined as:

[ \begin{align} y_{ij} &\sim \text{Beta}(\mu_{ij}, \phi_i) \ \text{logit}(\mu_{ij}) &= \alpha + X\beta + \gamma_i \end{align} ]

Where ( \alpha ) represents the common cross-batch average, ( X\beta ) captures biological covariates, and ( \gamma_i ) represents the batch-associated additive effect [32].

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete ComBat-met workflow from data input through batch-corrected output:

Figure 1: ComBat-met analysis workflow showing the sequence from raw data input through processing steps to corrected output.

Practical Implementation

For researchers implementing ComBat-met, the following code example demonstrates the basic function call using the R package:

The package supports advanced features including reference-batch correction and parallelization to improve computational efficiency with large datasets [36].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Experimental Design for Method Validation

To validate the performance of ComBat-met, comprehensive benchmarking analyses were conducted using simulated data with known ground truth. The simulation setup included:

- Dataset Characteristics: 1000 features with a balanced design involving two biological conditions and two batches across 20 samples [32].

- Differential Methylation: 100 out of 1000 features were simulated as truly differentially methylated, with methylation percentages higher under condition 2 than condition 1 by 10% [32].

- Batch Effects: Introduction of varying batch effect magnitudes, with methylation percentages in one batch differing by 0%, 2%, 5%, or 10%, and precision parameters varying from 1- to 10-fold between batches [32].

The simulation was repeated 1000 times, followed by differential methylation analysis. Performance was assessed using true positive rates (TPR) and false positive rates (FPR), calculated as the proportion of significant features among those that were and were not truly differentially methylated, respectively [32].

Comparative Performance Results

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance comparison between ComBat-met and alternative batch correction methods based on simulation studies:

Table 1: Performance comparison of batch correction methods for DNA methylation data

| Method | Core Approach | Median TPR | Median FPR | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-met | Beta regression with quantile matching | Highest | Controlled (0.05) | Preserves β-value distribution; Optimized for methylation data | Requires sufficient sample size per batch |

| M-value ComBat | Logit transformation followed by standard ComBat | Moderate | Controlled | Widely available; Familiar framework | Distributional inaccuracy for extreme β-values |

| SVA | Surrogate variable analysis on M-values | Moderate | Variable | Handles unknown batch effects | Can remove biological signal if confounded |

| Include Batch in Model | Direct covariate adjustment in linear model | Lower | Controlled | Simple implementation | Limited for complex batch structures |

| BEclear | Latent factor models | Lower | Slightly elevated | Directly models β-values | Less effective for strong batch effects |

| RUVm | Control-based removal of unwanted variation | Moderate | Variable | Uses control features | Requires appropriate control probes |

Note: TPR = True Positive Rate; FPR = False Positive Rate. Performance metrics based on simulated data with known ground truth [32] [36].

Application to TCGA Data

The practical utility of ComBat-met was demonstrated through application to breast cancer methylation data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Results showed that:

- Variance Explanation: ComBat-met consistently achieved the smallest percentage of batch-associated variation in both normal and tumor samples compared to alternative methods [36].

- Classification Improvement: In machine learning applications, batch adjustment using ComBat-met consistently improved classification accuracy of normal versus cancerous samples when using randomly selected methylation probes [36].

- Biological Signal Recovery: The method effectively recovered biologically meaningful signals while removing technical variations, as validated through known breast cancer subtype classifications [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Implementation Challenges

False Positive Results and p-value Inflation

Issue: Unexpectedly high numbers of significant results after batch correction, potentially indicating false positives.

Background: Several studies have reported that standard ComBat can systematically introduce false positive findings in DNA methylation data under certain conditions [33]. One study demonstrated that applying ComBat to randomly generated data produced alarming numbers of false discoveries, even with Bonferroni correction [33].

Solutions:

- Validate with Simulated Null Data: Generate data with no biological signal but similar experimental structure to assess baseline false positive rates [33].

- Check Batch-Condition Confounding: Ensure biological conditions are not completely confounded with batch structure, as this makes separation of technical and biological variance difficult [34].

- Avoid Over-Correction: Limit the number of batch factors corrected, as increasing the number of corrected factors exponentially increases false positive rates [33].

- Use Appropriate Sample Sizes: Larger sample sizes reduce but do not completely prevent false positive inflation [33].

Data Distribution Violations

Issue: Poor performance when data distribution assumptions are violated.

Background: Standard ComBat assumes normality, making it inappropriate for raw β-values. Even with M-value transformation, distributional issues may persist [32] [34].

Solutions:

- Use Distribution-Appropriate Methods: Apply ComBat-met instead of standard ComBat for β-values to respect their bounded nature [32].

- Diagnose Distribution Fit: Check Q-Q plots and distribution diagnostics before and after correction.

- Consider Alternative Transformations: For standard ComBat, ensure proper transformation to M-values, though ComBat-met eliminates this requirement [32].

Reference Batch Selection

Issue: Suboptimal performance when using reference batch adjustment.

Background: ComBat-met allows alignment to a reference batch, but inappropriate reference selection can introduce biases [32].

Solutions:

- Choose Technically Superior Batches: Select reference batches with highest data quality based on quality control metrics.

- Consider Biological Representation: Ensure reference batch adequately represents biological groups of interest.

- Validate Choice Sensitivity: Test multiple reference batches to assess result robustness.

Probe-Specific Batch Effects

Issue: Residual batch effects in specific probes after correction.

Background: Certain methylation probes are particularly susceptible to batch effects due to sequence characteristics, with 4649 probes consistently requiring high amounts of correction across datasets [34].

Solutions:

- Filter Problematic Probes: Consider removing persistently problematic probes identified in previous studies [34].

- Apply Probe-Specific Adjustments: Use methods that account for probe-specific technical characteristics.

- Implement Post-Correction Diagnostics: Check for residual batch effects stratified by probe type.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key software tools and resources for ComBat and ComBat-met implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-met | Beta regression-based batch correction | DNA methylation β-values | R package: ComBat_met() function |

| sva Package | Standard ComBat implementation | Gene expression, M-values | R package: combat() function |

| ChAMP Pipeline | Integrated methylation analysis | EPIC/450K array data | Includes ComBat as option |

| methylKit | DNA methylation analysis | Simulation and differential analysis | Used for performance benchmarking |

| betareg | Beta regression modeling | General proportional data | Core dependency for ComBat-met |

| TCGA Data | Real-world validation dataset | Breast cancer and other malignancies | Publicly available from NCI |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive Batch Effect Correction Protocol

For researchers implementing batch effect correction in DNA methylation studies, the following detailed protocol ensures robust results:

Pre-correction Quality Control

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize batch-associated clustering

- Calculate variance explained by batch versus biological factors

- Identify potential batch-condition confounding

- Check for missing data patterns correlated with batch

Method Selection Criteria

- Use ComBat-met for β-values without transformation

- Consider M-value ComBat only for small datasets when ComBat-met is computationally prohibitive

- Apply reference batch correction when aligning to a specific dataset

- Use cross-batch averaging for balanced multi-batch studies

Parameter Optimization

- For small sample sizes (n < 10 per batch), enable parameter shrinkage

- For large datasets, implement parallel processing to reduce computation time

- Adjust model specifications to include biological covariates when appropriate

Post-correction Validation

- Re-run PCA to confirm batch effect removal

- Verify biological signals are preserved using known positive controls

- Check that corrected values maintain appropriate distribution (β-values between 0-1)

- Test sensitivity to parameter variations

Neural Network Validation Protocol

To evaluate the impact of batch correction on downstream predictive models, the following protocol can be implemented:

Probe Selection: Randomly select three methylation probes in each iteration to simulate minimal, unbiased feature sets [36].

Classifier Architecture: Implement a feed-forward, fully connected neural network with two hidden layers for classifying normal versus cancerous samples [36].

Performance Assessment: Calculate and compare accuracy for models trained on unadjusted versus batch-adjusted data across multiple iterations [36].

This approach demonstrates the practical utility of batch correction in improving predictive modeling performance while avoiding cherry-picking of features that might artificially inflate performance metrics.

Critical Methodological Considerations

When to Avoid ComBat Methods

Despite their utility, ComBat methods should be avoided in certain scenarios:

- Complete Confounding: When batch and biological conditions are perfectly confounded, no statistical method can reliably separate technical from biological variance [34].

- Extreme Small Sample Sizes: With fewer than 5 samples per batch, parameter estimates become unstable, potentially introducing more artifacts than they remove [33].

- Inappropriate Data Types: Standard ComBat should not be applied to β-values without transformation, as distributional assumptions are violated [32].

Emerging Alternatives and Extensions

The field continues to evolve with new approaches addressing ComBat limitations:

- iComBat: An incremental framework for batch effect correction in DNA methylation array data, particularly useful for repeated measurements [37].

- Harmonization Methods: Approaches like those used in medical imaging may offer alternative strategies for certain data types [35].

- Cross-Platform Validation: Always validate findings using multiple batch correction approaches to ensure result robustness.

Visual Decision Framework

The following diagram provides a systematic approach for selecting appropriate batch correction strategies based on data characteristics:

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting appropriate batch correction methods based on data characteristics and experimental design.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I NOT apply batch correction to my single-cell RNA-seq data? Batch correction is not always appropriate. You should avoid or carefully evaluate using it when:

- Your "batches" are actually different biological conditions, treatments, or time points that you want to compare. Over-correction can remove the biological variation you are trying to study [38].

- You are analyzing a homogeneous population of cells (e.g., a single cell line) with limited inherent biological variation to anchor the integration, as this can lead to spurious alignment [38].

- Your goal is to identify dataset-specific cell states or population structures, as aggressive integration can mask these differences [39].

2. My data is over-corrected after using Seurat's CCA. What can I do? Seurat's CCA method can sometimes be overly aggressive in removing variation. A recommended alternative is to use Seurat's RPCA (Reciprocal PCA) workflow, which is designed to prioritize the conservation of biological variation over complete batch removal [38]. Benchmarking studies have shown that different methods balance batch removal and bio-conservation differently, so trying a less aggressive method like RPCA, Scanorama, or scVI may be beneficial [40].

3. How do I choose between Harmony, Seurat, and LIGER for my project? The choice depends on your data and goals. The table below summarizes key characteristics based on independent benchmarking [40]:

| Method | Key Strength | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Harmony | Fast, sensitive, accurate; performs well on scATAC-seq data [41] [40] | Large datasets; integrating data from multiple donors, tissues, or technologies [41]. |

| Seurat (CCA & RPCA) | Well-established, comprehensive workflow; RPCA prioritizes bio-conservation [38] [40] | Standard integration tasks; when a full-featured pipeline is desired [40]. |

| LIGER | Identifies shared and dataset-specific factors; good for cross-species and multi-omic integration [39] [42] [40] | Comparing and contrasting datasets; multi-modal integration (e.g., RNA-seq + ATAC-seq) [39] [42]. |

4. Should I use SCTransform normalization before integration?

While SCTransform is a powerful normalization method, its use before integration requires caution. The SCTransform method can be used, but it is not a direct substitute for batch correction algorithms like Harmony or IntegrateData [43]. For some integration methods, using standard log-normalization may be more straightforward and equally effective [38]. It is critical to follow the specific requirements of your chosen integration method, as some may not accept SCTransform-scaled data [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Mixing After Integration

Problem: After running an integration method (e.g., Harmony, Seurat), cells from different batches still form separate clusters in visualizations like UMAP.

Solutions:

- Check Biological Overlap: Confirm that the same cell types are present across all batches. Integration methods can only align shared cell types or states [38].

- Adjust Method Parameters: Increase the strength of the integration. In Harmony, you can increase the

thetaparameter, which controls the diversity penalty, to encourage better mixing. Re-run the algorithm with more iterations if it did not converge [44]. - Try an Alternative Method: If one method fails, try another. Benchmarking has shown that no single method outperforms all others in every scenario [40]. For example, if Seurat's CCA is too aggressive, try RPCA or Scanorama [38] [40].

Issue 2: Loss of Biological Variation After Integration

Problem: Biologically distinct cell populations (e.g., different treatment conditions or known subtypes) are artificially merged after integration.

Solutions:

- Re-evaluate the Need for Correction: This is a classic sign of over-correction. If the "batch" you are correcting for is a key biological variable, you should not integrate across it [38].

- Use a Less Aggressive Workflow: Switch to an integration method known to better preserve biological variation. Seurat's RPCA and Scanorama have been benchmarked to prioritize bio-conservation [38] [40].

- Validate with Marker Genes: Always check the expression of known marker genes for the lost populations in the integrated space to confirm they have been erroneously merged [45].

Issue 3: Harmony Fails to Converge or is Slow

Problem: Harmony throws warnings like "did not converge in 25 iterations" or runs very slowly on large datasets.

Solutions:

- Increase Iterations: Set the

max.iter.harmonyparameter to a higher value (e.g., 50 or 100) to allow the algorithm more time to converge [44]. - Optimize Performance:

- Ensure your R installation is linked with OPENBLAS instead of BLAS, as this can substantially speed up Harmony's performance [46].

- By default, Harmony turns off multi-threading to avoid inefficient CPU usage. For very large datasets (>1 million cells), you can try gradually increasing the

ncoresparameter to utilize multiple threads [46].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Generic Workflow for Single-Cell Data Integration

The following diagram outlines the standard steps for integrating single-cell datasets, which is common to most analysis pipelines.

Detailed Method-Specific Protocols

1. Harmony Integration within a Seurat Workflow This protocol details how to run Harmony on a Seurat object after standard preprocessing.

- Input: A Seurat object containing multiple datasets, with PCA computed.

- Code Example:

- Key Parameters:

2. LIGER for Multi-Modal Integration LIGER uses integrative Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (iNMF) to jointly define shared and dataset-specific factors.

- Input: Multiple normalized count matrices (e.g., from scRNA-seq and snATAC-seq).

- Workflow Diagram:

- Key Parameters:

k: The number of factors (metagenes). This is a critical parameter that determines the granularity of the inferred biological signals [39].lambda: The tuning parameter that adjusts the relative strength of dataset-specific versus shared factors. A higherlambdavalue yields more dataset-specific factors [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key computational "reagents" and tools essential for performing single-cell data integration.

| Item | Function & Explanation | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger | A set of analysis pipelines from 10x Genomics that process raw sequencing data (FASTQ) into aligned reads and a feature-barcode matrix. This is the foundational starting point for many analyses [47]. | Data Preprocessing |

| Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) | A filtered set of genes that exhibit high cell-to-cell variation. Focusing on HVGs reduces noise and computational load, and has been shown to improve the performance of data integration methods [40]. | Normalization & Feature Selection |

| PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | A linear dimensionality reduction technique. It is the default method in many workflows to create an initial low-dimensional embedding of the data, which is often used as direct input for integration algorithms like Harmony [41] [44]. | Dimensionality Reduction |

| UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) | A non-linear dimensionality reduction technique used widely for visualizing single-cell data in 2D or 3D. It allows researchers to visually assess the effectiveness of integration and the structure of cell clusters [47]. | Visualization & Exploration |

| Benchmarking Metrics (e.g., kBET, ASW, LISI) | A set of quantitative metrics used to evaluate integration quality. They separately measure batch effect removal (e.g., kBet, iLISI) and biological conservation (e.g., cell-type ASW, cLISI), providing an objective score for method performance [40]. | Result Validation |

Batch effects represent systematic technical variations between datasets generated under different conditions (e.g., different sequencing runs, protocols, or laboratories). These non-biological variations can obscure true biological signals and lead to incorrect conclusions in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis [9]. Traditional batch effect correction methods often fail to preserve the intrinsic order of gene expression levels within cells, potentially disrupting biologically meaningful patterns crucial for downstream analysis [48].

Order-preserving batch effect correction addresses this limitation by maintaining the relative rankings of gene expression levels during the correction process. This approach ensures that biologically significant expression patterns remain intact after integration, providing more reliable data for identifying cell types, differential expression, and gene regulatory relationships [48].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Batch Effect: Systematic technical differences between datasets that are not due to biological variation. These can stem from differences in sample preparation, sequencing runs, reagents, or instrumentation [9].

Order-Preserving Feature: A property of batch effect correction methods that maintains the relative rankings or relationships of gene expression levels within each batch after correction [48].

Monotonic Deep Learning Network: A specialized neural network architecture that preserves the order relationships in data during transformation, making it particularly suitable for order-preserving batch correction [48].

Inter-gene Correlation: The statistical relationship between expression patterns of different genes, which should be preserved after batch correction to maintain biological validity [48].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Monotonic Deep Learning Framework for Batch Correction

Protocol Title: Implementation of Order-Preserving Batch Effect Correction Using Monotonic Deep Learning Networks

Primary Citation: [48]

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Preprocessing: Begin with raw scRNA-seq count matrices from multiple batches. Perform standard quality control including removal of low-quality cells, normalization for sequencing depth, and identification of highly variable genes.

Initial Clustering: Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., graph-based clustering) within each batch to identify preliminary cell groupings. Estimate probability of each cell belonging to each cluster.

Similarity Calculation: Utilize both within-batch and between-batch nearest neighbor information to evaluate similarity among obtained clusters. Perform intra-batch merging and inter-batch matching of similar clusters.