Benchmarking Functional Genomics Computational Tools: A Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on benchmarking computational tools in functional genomics.

Benchmarking Functional Genomics Computational Tools: A Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on benchmarking computational tools in functional genomics. It covers the foundational principles of rigorous benchmarking, explores major tools and their applications in areas like drug discovery and single-cell analysis, addresses common computational challenges and optimization strategies, and reviews established benchmarks and validation frameworks. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select, validate, and optimally apply computational methods, thereby enhancing the reliability and impact of genomic research.

The Why and How of Benchmarking: Core Principles for Genomic Tool Evaluation

Defining the Purpose and Scope of a Benchmarking Study

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Selecting the Appropriate Benchmarking Study Type

Problem: A researcher is unsure whether to conduct a neutral benchmark for the community or a focused benchmark to demonstrate a new method's advantages.

Solution: Determine the study type based on your primary goal and available resources [1].

| Step | Action | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define primary objective | Community recommendation vs. new method demonstration [1] |

| 2 | Assess available resources | Time, computational power, dataset availability [1] |

| 3 | Determine method selection | Comprehensive vs. representative subset [1] |

| 4 | Plan evaluation metrics | Performance rankings vs. specific advantages [1] |

Guide: Resolving Ground Truth Limitations in Functional Genomics

Problem: A researcher cannot establish a reliable ground truth for evaluating computational tools on real genomic data.

Solution: Employ a combination of experimental and computational approaches to establish the most reliable benchmark possible [1] [2].

| Approach | Methodology | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Spike-in | Adding synthetic RNA/DNA at known concentrations [1] | Sequencing accuracy benchmarks [1] | May not reflect native molecular variability [1] |

| Cell Sorting | FACS sorting known subpopulations before scRNA-seq [1] | Cell type identification methods [1] | Technical artifacts from sorting process [1] |

| Mock Communities | Combining titrated proportions of known organisms [2] | Microbiome analysis tools [2] | Artificial, may oversimplify reality [2] |

| Integrated Arbitration | Consensus from multiple technologies and callers [2] | Variant calling benchmarks [2] | Disagreements may create incomplete standards [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental purpose of a benchmarking study in computational genomics?

Benchmarking studies aim to rigorously compare the performance of different computational methods using well-characterized datasets to determine their strengths and weaknesses, and provide recommendations for method selection [1]. They help bridge the gap between tool developers and biomedical researchers by providing scientifically rigorous knowledge of analytical tool performance [2].

How comprehensive should my method selection be for a neutral benchmark?

A neutral benchmark should be as comprehensive as possible, ideally including all available methods for a specific type of analysis [1]. You can define inclusion criteria such as: (1) freely available software implementations, (2) compatibility with common operating systems, and (3) successful installation without excessive troubleshooting. Any exclusion of widely used methods should be clearly justified [1].

What are the main types of reference datasets I can use, and when should I use each?

| Dataset Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated Data | Computer-generated with known ground truth [1] | Known true signal; can generate large volumes; systematic testing [1] | May not reflect real data complexity; model bias [1] |

| Real Experimental Data | From actual experiments; may lack ground truth [1] | Real biological variability; actual experimental conditions [1] | Difficult to calculate performance metrics; no known truth [1] |

| Designed Experimental Data | Engineered experiments with introduced truth [1] | Combines real data with known signals [1] | May not represent natural variability; complex to create [1] |

How can I avoid bias when benchmarking my own method against competitors?

To avoid self-assessment bias: (1) Use the same parameter tuning procedures for all methods, (2) Avoid extensively tuning your method while using defaults for others, (3) Consider involving original method authors, (4) Use blinding strategies where possible, and (5) Clearly report any limitations in the benchmarking design [1]. The benchmarking should accurately represent the relative merits of all methods, not disproportionately advantage your approach [1].

What are the key differences between community benchmarks like GUANinE or GenomicBenchmarks and individual research benchmarks?

| Aspect | Community Benchmarks | Individual Research Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Large-scale (e.g., ~70M training examples in GUANinE) [3] | Typically smaller, focused datasets [1] |

| Scope | Multiple tasks (e.g., functional element annotation, expression prediction) [3] | Specific to research question or method [1] |

| Data Control | Rigorous cleaning, repeat-downsampling, GC-balancing [3] | Variable control based on resources [1] |

| Adoption | Standardized comparability across studies [3] | Specific to publication needs [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Benchmarking | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | Standardized genomic coordinates for alignment and annotation [4] | GRCh38 (human), dm6 (drosophila) [4] |

| Epigenomic Data | Ground truth for regulatory element prediction [3] | ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics [1] [4] |

| Cell Line Mixtures | Controlled cellular inputs for method validation [1] | Mixed cell lines, pseudo-cells [1] |

| Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA/DNA molecules for quantification accuracy [1] | Commercial spike-in reagents (e.g., ERCC) [1] |

| Validated Element Sets | Curated positive controls for specific genomic elements [4] | FANTOM5 enhancers, EPD promoters [4] |

| Containerization Tools | Reproducible software environments for method comparison [2] | Docker, Singularity, Conda environments [2] |

| Benchmark Datasets | Standardized collections for model training and evaluation [4] [3] | genomic-benchmarks, GUANinE [4] [3] |

Selecting Methods for a Fair and Comprehensive Comparison

FAQs on Benchmarking Functional Genomics Tools

1. What are the most common pitfalls in benchmarking genomic tools, and how can I avoid them? A major pitfall is relying on incomplete or non-reproducible data and code from publications, which can consistently lead to tools underperforming in practice [5]. To avoid this, concentrate your benchmarking efforts on a smaller, representative set of tools for which the model baselines and data can be reliably obtained and reproduced [5]. Furthermore, ensure your evaluation uses tasks that are aligned with open biological questions, such as gene regulation, rather than generic classification tasks from machine learning literature that may be disconnected from real-world use [5].

2. My benchmark results are inconsistent. How can I improve the reliability of my comparisons? Inconsistency often stems from a lack of standardized data and procedures. You can address this by using curated, ready-to-use benchmarking datasets that represent a broad biological diversity, such as those from the EasyGeSe resource [6]. This resource provides data from multiple species (e.g., barley, maize, rice, soybean) in convenient formats, which standardizes the input data and evaluation procedures. This simplifies benchmarking and enables fair, reproducible comparisons between different methods [6].

3. How can I ensure my genomic annotation data is reusable and interoperable for future studies? To enhance data interoperability and reusability, ensure your annotations and their provenance are stored using a structured, semantic framework. Platforms like SAPP (Semantic Annotation Platform with Provenance) automatically store both the annotation results and their dataset- and element-wise provenance in a Linked Data format (RDF) using controlled vocabularies and ontologies [7]. This approach, which adheres to FAIR principles, allows for complex queries across multiple genomes and facilitates seamless integration with external resources [7].

4. What should I do if a tool fails to run during a benchmark?

First, check for common system issues. Use commands like ping to test basic network connectivity to any required servers and ip addr to view the status of all your system's network interfaces [8]. If the tool is containerized, ensure you are using the correct runtime environment. For example, the FANTASIA annotation tool is available as an open-access Singularity container, so verifying you have Singularity installed and the container image properly pulled is a key step [9].

5. How do I select the right performance metrics for my benchmark? The choice of metric should be dictated by your biological question. For genomic prediction tasks, a common quantitative metric is Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), which measures the correlation between predicted and observed phenotypic values [6]. You should also consider computational performance metrics like runtime and RAM usage, as these determine the practical utility of a tool, especially with large datasets [6]. A comprehensive benchmark should report on all these aspects: predictive performance, runtime, memory efficiency, and query precision [10].

Benchmarking Performance Data

The table below summarizes quantitative data from a benchmark of genomic prediction methods, illustrating how performance varies across species and algorithms [6].

| Species | Trait | Parametric Model (r) | Non-Parametric Model (r) | Performance Gain (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | Disease Resistance | 0.75 | 0.77 (XGBoost) | +0.02 |

| Common Bean | Days to Flowering | 0.65 | 0.68 (LightGBM) | +0.03 |

| Lentil | Days to Maturity | 0.70 | 0.72 (Random Forest) | +0.02 |

| Maize | Yield | 0.80 | 0.82 (XGBoost) | +0.02 |

| Average across 10 species | Various | ~0.62 | ~0.64 (XGBoost) | +0.025 |

Key Insights: Non-parametric machine learning methods like XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest generally offer modest but statistically significant gains in predictive accuracy compared to parametric methods. They also provide major computational advantages, with model fitting times typically an order of magnitude faster and RAM usage approximately 30% lower than Bayesian alternatives [6].

Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Benchmarking Genomic Tools

This protocol provides a generalizable methodology for conducting a fair and comprehensive comparison of computational tools in functional genomics.

1. Objective Definition and Task Design

- Define Biological Objective: Clearly state the biological question (e.g., predicting gene function in non-model organisms, identifying genomic intervals) [9] [10].

- Design Biologically-Aligned Tasks: Frame benchmarking tasks around open biological questions, such as gene regulation, rather than abstract machine learning challenges [5].

2. Tool and Dataset Curation

- Select a Representative Tool Set: Focus on a manageable set of tools for which code, models, and baseline data can be reliably obtained to ensure full reproducibility [5].

- Assemble Diverse and Curated Datasets: Use datasets from multiple species to ensure biological representativeness. Resources like EasyGeSe provide pre-filtered, formatted data from various species (barley, common bean, lentil, etc.), which removes practical barriers and ensures consistency [6].

3. Execution and Performance Measurement

- Run Standardized Comparisons: Execute all tools on the curated datasets using the same computational environment.

- Measure Multiple Metrics: Collect data on:

4. Data Management and FAIRness

- Capture Provenance: Use a platform like SAPP to automatically track and store both dataset-wise (tools, versions, parameters) and element-wise (individual prediction scores) provenance [7].

- Store in Interoperable Formats: Employ semantic web technologies (RDF, ontologies) to make annotation data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) [7].

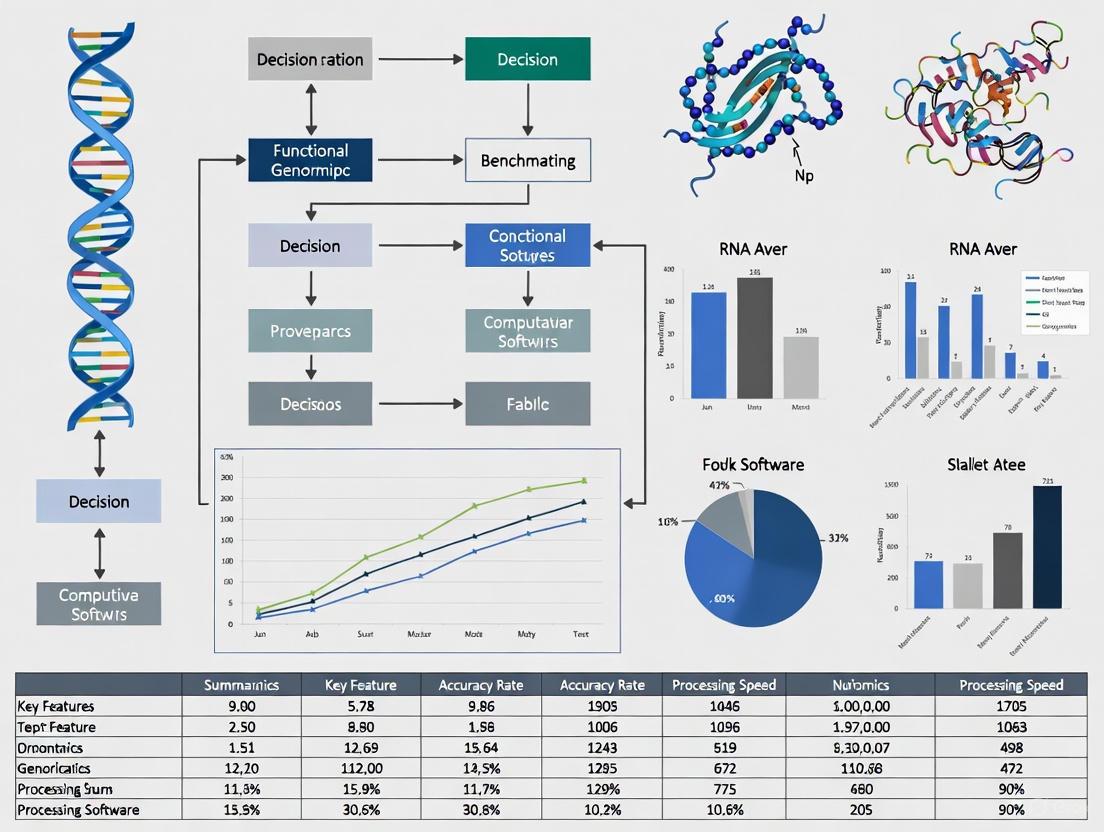

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this benchmarking process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists essential "research reagents" – key datasets, software, and infrastructure – required for conducting rigorous genomic tool benchmarks.

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| EasyGeSe Datasets [6] | Data Resource | Provides curated, multi-species genomic and phenotypic data in ready-to-use formats for standardized model testing. |

| segmeter Framework [10] | Benchmarking Software | A specialized framework for the systematic evaluation of genomic interval querying tools on runtime, memory, and precision. |

| SAPP Platform [7] | Semantic Infrastructure | An annotation platform that stores results and provenance in a FAIR-compliant Linked Data format, enabling complex queries and interoperability. |

| FANTASIA Pipeline [9] | Functional Annotation Tool | An open-access tool that uses protein language models for high-throughput functional annotation, especially useful for non-model organisms. |

| Singularity Container [9] | Computational Environment | Ensures tool dependency management and run-to-run reproducibility by encapsulating the entire software environment. |

Workflow for Functional Annotation Benchmarking

For a benchmark focused specifically on functional annotation tools, the process can be detailed in the following workflow, which highlights the role of modern AI-based methods.

In functional genomics research, the choice between using simulated (synthetic) or real datasets is a critical foundational step that directly impacts the reliability, scope, and applicability of your findings. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help researchers navigate this decision, framed within the context of benchmarking computational tools for functional genomics.

Quick Comparison: Simulated vs. Real Data

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each data type to help inform your initial selection.

| Feature | Simulated Data | Real Data |

|---|---|---|

| Data Origin | Artificially generated by computer algorithms [11] | Collected from empirical observations and natural events [11] |

| Privacy & Regulation | Avoids regulatory restrictions; no personal data exposure [11] | Subject to privacy laws (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR); requires anonymization [11] |

| Cost & Speed | High upfront investment in simulation setup; low cost to generate more data [11] | Continuously high costs for collection, storage, and curation [11] |

| Accuracy & Realism | Risk of oversimplification; may lack complex real-world correlations [11] | Authentically represents real-world biological complexity and noise [12] |

| Availability for Rare Events/Conditions | Can be programmed to include specific, rare scenarios on demand [11] | Naturally rare, making data collection difficult and expensive [11] |

| Bias Control | Can be designed to minimize inherent biases | May contain unknown or uncontrollable sampling and population biases |

| Ideal Application | Method validation, testing hypotheses, and modeling scenarios where real data is unavailable [13] [14] [12] | Model training for final validation, and studies where true representation is critical [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When is synthetic data the only viable option for my functional genomics study? Synthetic data is often the only choice when real data is inaccessible due to privacy constraints, is too costly to obtain, or when you need to model specific biological scenarios that have not yet been observed in reality. For instance, simulating genomic datasets with known genotype-phenotype associations is indispensable for validating new statistical methods designed to detect disease-predisposing genes [13] [14].

2. My machine learning model trained on synthetic data performs poorly on real-world data. What went wrong? This common issue, known as the "reality gap," often occurs when the synthetic data lacks the full complexity, noise, and intricate correlations present in real biological systems [11]. The synthetic dataset may have been oversimplified or failed to capture crucial outlier information. To troubleshoot, verify your simulation model against any available real data and consider augmenting your training set with a mixture of synthetic and real data, if possible.

3. How can I ensure my simulated genomic data is of high quality and useful? Quality assurance for simulated data involves several key steps:

- Validation: Compare the output of your simulator against established biological knowledge or any small-scale real datasets that are available. Check if key summary statistics (e.g., linkage disequilibrium patterns, allele frequency spectra) match expectations [12] [15].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test how changes in your simulation parameters affect the final output. A robust simulation should behave in a predictable and biologically plausible manner.

- Documentation: Meticulously document all assumptions, parameters, and algorithms used in the simulation process. This transparency is crucial for other researchers to assess and build upon your work [14].

4. What are the main regulatory advantages of using synthetic data in drug development? Synthetic data does not contain personally identifiable information (PII), which resolves the privacy/usefulness dilemma inherent in using real patient data [11]. This eliminates concerns about violating regulations like HIPAA or GDPR, making it easier to share datasets with third-party collaborators, accelerate innovation, and monetize research tools without legal hurdles [11].

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation and Application

Protocol 1: Generating a Simulated Dataset for Tool Benchmarking

This protocol outlines the steps for using a forward-time population simulator to generate synthetic genomic data, a common method for creating realistic case-control study data [12].

1. Define Research Objective and Simulation Parameters: Clearly state the goal of your benchmark (e.g., testing a new variant-caller's power to detect rare variants). Define key parameters: * Demographic Model: Specify population size, growth curves, and migration events [15]. * Genetic Model: Set mutation and recombination rates, and define disease models (e.g., effect sizes for causal variants) [12]. * Study Design: Determine the number of cases and controls, and the genomic regions to simulate.

2. Select and Configure a Simulation Tool: Choose an appropriate simulator from resources like the Genetic Simulation Resources (GSR) catalogue [13] [14]. Configure the tool using the parameters from Step 1. Example tools include genomeSIMLA [12] or msprime [15].

3. Execute the Simulation and Generate Data: Run the simulation to output synthetic genomic data (e.g., in VCF format) and associated phenotypes. This dataset now has a known "ground truth."

4. Validate Simulated Data Quality: Compute population genetic statistics (e.g., allele frequencies, linkage disequilibrium decay) on the simulated data and compare them to empirical data from public repositories to ensure biological realism [12].

5. Apply Computational Tools for Benchmarking: Use the synthetic dataset as input for the computational tools you are benchmarking. Since you know the true positive variants and associations, you can precisely calculate performance metrics like sensitivity, specificity, and false discovery rate.

The workflow for this protocol is standardized as follows:

Protocol 2: A Machine Learning Workflow Combining Simulated and Real Data

This protocol is effective for training robust models when real data is limited, a technique successfully applied in demographic inference from genomic data [15].

1. Model and Parameter Definition: Define the demographic or genetic model and the parameters to be inferred (e.g., population split times, migration rates).

2. Large-Scale Simulation: Use a coalescent-based simulator like msprime to generate a massive number of synthetic datasets (e.g., 10,000) by drawing parameters from broad prior distributions [15].

3. Summary Statistics Calculation: For each simulated dataset, compute a comprehensive set of summary statistics (e.g., site frequency spectrum, Fst, LD statistics) that serve as features for the machine learning model [15].

4. Supervised Machine Learning Training: Train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., a Neural Network/MLP, Random Forest, or XGBoost) to learn the mapping from the summary statistics (input) to the simulation parameters (output) [15].

5. Model Validation and Application to Real Data: Validate the trained model on a held-out test set of simulated data. Finally, apply the model by inputting summary statistics calculated from your real, observed genomic data to infer the underlying parameters.

The workflow for this hybrid approach is as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Tools for Data Simulation

The table below lists essential software tools and resources for generating and working with simulated genetic data.

| Tool Name | Function | Key Application in Functional Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Simulation Resources (GSR) Catalogue | A curated database of genetic simulation software, allowing comparison of tools based on over 160 attributes [13] [14]. | Finding the most appropriate simulator for a specific research question and study design. |

| Forward-Time Simulators (e.g., genomeSIMLA, simuPOP) | Simulates the evolution of a population forward in time, generation by generation, allowing for complex modeling of demographic history and selection [13] [12]. | Simulating genome-wide association study (GWAS) data with realistic LD patterns and complex traits [12]. |

| Backward-Time (Coalescent) Simulators (e.g., msprime) | Constructs the genealogy of a sample retrospectively, which is computationally highly efficient for neutral evolution [13] [15]. | Generating large-scale genomic sequence data for population genetic inference and method testing [15]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., MLP, XGBoost) | Supervised learning algorithms that can be trained on simulated data to infer demographic and genetic parameters from real genomic data [15]. | Bridging the gap between simulation and reality for parameter inference and predictive modeling [15]. |

Establishing Ground Truth and Performance Metrics

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main types of ground truth used in functional genomics benchmarks? Ground truth in functional genomics benchmarks primarily comes from two sources: experimental and computational. Experimental ground truth includes spike-in controls with known concentrations (e.g., ERCC spike-ins for RNA-seq) and specially designed experimental datasets with predefined ratios, such as the UHR and HBR mixtures used in the SEQC project [16]. Computational ground truth is often established through simulation, where data is generated with known properties, though this relies on modeling assumptions that may introduce bias [16] [1].

Why is my benchmarking result showing inconsistent performance across different metrics? Different performance metrics capture distinct aspects of method performance. A method might excel in one area, such as identifying true positives (high recall), while performing poorly in another, such as minimizing false positives (low precision). It is essential to select a comprehensive set of metrics that align with your specific biological question and application needs. Inconsistent results often highlight inherent trade-offs in method design [1].

How do I handle a task failure due to insufficient memory for a Java process?

This common error often manifests as a command failing with a non-zero exit code. Check the job.err.log file for memory-related exceptions. The solution is to increase the value of the "Memory Per Job" parameter, which directly controls the -Xmx Java parameter [17].

My RNA-seq task failed with a chromosome name incompatibility error. What does this mean? This error occurs when the gene annotation file (GTF/GFF) and the genome reference file use different naming conventions (e.g., "1" vs. "chr1") or are from different genome builds (e.g., GRCh37/hg19 vs. GRCh38/hg38). Ensure that all your reference files are from the same build and use consistent chromosome naming conventions [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Normalization Performance Evaluation Without Ground Truth

Problem: You need to evaluate RNA-seq normalization methods but lack experimental ground truth data.

Diagnosis: Relying solely on downstream analyses like differential expression (DE) can be problematic, as the choice of DE tool introduces its own biases and parameters. Qualitative or data-driven metrics can be directly optimized by certain algorithms, making them unreliable for unbiased comparison [16].

Solution:

- Utilize Public Spike-in Datasets: Leverage existing public RNA-seq assays that include external spike-in controls. These provide an experimental ground truth for benchmarking [16].

- Adopt the cdev Metric: Use the condition-number based deviation (cdev) to quantitatively measure how much a normalized expression matrix differs from a ground-truth normalized matrix. A lower cdev value indicates better performance [16].

- Simulate Data Cautiously: If using simulated data, rigorously demonstrate that the simulations reflect key properties of real data to ensure relevant and meaningful results [1].

Issue: Benchmarking Fails to Differentiate Method Performance

Problem: Your benchmark results show that all methods perform similarly, making it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions.

Diagnosis: This can happen if the benchmark datasets are not sufficiently challenging, lack a clear ground truth, or if the evaluation metrics are not sensitive enough to capture key performance differences [18].

Solution:

- Select Diverse and Challenging Tasks: Choose tasks that represent realistic biological challenges. For example, DNALONGBENCH includes five distinct long-range DNA prediction tasks, such as contact map prediction and enhancer-target gene interaction, which present varying levels of difficulty for different models [18].

- Include a Variety of Models: Compare your methods against a range of models, including simple baselines (e.g., CNNs), state-of-the-art expert models, and modern foundation models. This helps contextualize the performance [18].

- Use Stratified Evaluation: For certain tasks, use metrics like the stratum-adjusted correlation coefficient, which can provide a more nuanced view of performance than a single global score [18].

Issue: Tool Execution Failure Due to Configuration Errors

Problem: A bioinformatics tool or workflow fails to execute on a computational platform (e.g., the Cancer Genomics Cloud).

Diagnosis: The error can stem from various configuration issues, such as incorrect Docker image names, insufficient disk space, or invalid input file structures [17].

Solution: Follow a systematic troubleshooting checklist:

- Check the Task Error Message: Start with the error message on the task page for immediate clues (e.g., "Docker image not found" or "Insufficient disk space") [17].

- Inspect Stats & Logs: If the error message is unclear, use the platform's "View stats & logs" panel.

- Review Job Logs: Examine the

job.err.logfile for application-specific error messages (e.g., memory exceptions for Java tools) [17]. - Verify Input Files and Metadata: Ensure input files are compatible and have the required metadata. For RNA-seq tools, confirm that genome and gene annotation references are from the same build [17].

- Check Resource Allocation: Ensure that the computational instance allocated for the task has sufficient memory, CPU, and disk space as required by the tool [17].

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking Data

Table 1: Common Performance Metrics for Functional Genomics Tool Benchmarking

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Application Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Performance | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) | Enhancer annotation, eQTL prediction [18] | Measures the ability to distinguish between classes; higher is better. |

| Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) | Enhancer annotation, eQTL prediction [18] | More informative than AUROC for imbalanced datasets; higher is better. | |

| Regression & Correlation | Pearson Correlation | Contact map prediction, gene expression prediction [18] | Measures linear relationship between predicted and true values. |

| Stratum-Adjusted Correlation Coefficient (SCC) | Contact map prediction [18] | Evaluates reproducibility of contact maps, accounting for stratum effects. | |

| Normalization Quality | Condition-number based deviation (cdev) | RNA-seq normalization [16] | Quantifies deviation from a ground-truth expression matrix; lower is better. |

| Error Measurement | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Transcription initiation signal prediction [18] | Measures the average squared difference between predicted and true values. |

Table 2: Overview of Benchmarking Datasets and Their Applications

| Benchmark Suite | Featured Tasks | Sequence Length | Key Applications | Ground Truth Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNALONGBENCH [18] | Enhancer-target gene interaction, eQTL, 3D genome organization, regulatory activity, transcription initiation | Up to 1 million bp | Evaluating DNA foundation models, long-range dependency modeling | Experimental data (e.g., ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, Hi-C) |

| cdev & Spike-in Collection [16] | RNA-seq normalization | N/A | Evaluating and comparing RNA-seq normalization methods | Public RNA-seq assays with external spike-in controls |

| BEND & LRB [18] | Regulatory element identification, gene expression prediction | Thousands to long-range | Benchmarking DNA language models | Experimental and simulated data |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Ground Truth with RNA-seq Spike-ins

Purpose: To create a benchmark dataset for evaluating RNA-seq normalization methods using external RNA spike-in controls [16].

Materials:

- Biological RNA samples

- External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) spike-in mix

- RNA-seq library preparation kit

- Sequencing platform

Methodology:

- Spike-in Addition: Add a known, constant concentration of ERCC spike-ins to each biological RNA sample prior to library preparation [16].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed with standard RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing protocols.

- Data Processing: Map sequencing reads to a combined reference genome that includes both the target organism's genome and the ERCC spike-in sequences.

- Ground Truth Establishment: The known concentration and identity of the spike-ins serve as the ground truth. A correctly normalized dataset should minimize variation in the measured levels of these spike-ins across samples [16].

Protocol 2: Designing a Neutral Benchmarking Study

Purpose: To conduct an unbiased, systematic comparison of multiple computational methods for a specific functional genomics analysis [1].

Materials:

- A set of computational methods to be evaluated

- Reference datasets (simulated and/or experimental)

- High-performance computing resources

Methodology:

- Define Scope and Select Methods: Clearly define the goal of the benchmark. For a neutral benchmark, aim to include all relevant methods, or define clear, unbiased inclusion criteria (e.g., software availability, ease of installation). Justify the exclusion of any widely used methods [1].

- Curate Benchmarking Datasets: Select a variety of datasets that represent different challenges and conditions. These can include:

- Execute Method Comparisons: Run all selected methods on the benchmark datasets. To ensure fairness, avoid extensively tuning parameters for one method while using defaults for others. Involving method authors can help ensure each method is evaluated under optimal conditions [1].

- Analyze and Report Results: Use a comprehensive set of performance metrics. Summarize results in the context of the benchmark's purpose, providing clear guidelines for users and highlighting weaknesses for developers [1].

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Diagram 1: Functional Genomics Benchmarking Workflow

Functional Genomics Benchmarking Workflow

Diagram 2: Systematic Troubleshooting Logic

Systematic Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Benchmarking

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Provides known-concentration RNA transcripts added to samples before sequencing to create an experimental ground truth for normalization [16]. | Benchmarking RNA-seq normalization methods [16]. |

| UHR/HBR Sample Mixtures | Commercially available reference RNA samples mixed at predefined ratios (e.g., 1:3, 3:1) to create samples with known expression ratios [16]. | Validating gene expression measurements and titration orders in RNA-seq data [16]. |

| Public Dataset Collections | Pre-compiled, well-annotated experimental data (e.g., from ENCODE, SEQC) used as benchmark datasets, often including various assays like ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq [18]. | Training and evaluating models for tasks like enhancer annotation or chromatin interaction prediction [18]. |

| Specialized Benchmark Suites | Integrated collections of tasks and datasets designed for standardized evaluation of computational models (e.g., DNALONGBENCH, BEND) [18]. | Rigorously testing the performance of DNA foundation models and other deep learning tools on long-range dependency tasks [18]. |

Essential Guidelines for Rigorous and Unbiased Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Benchmarking Design

FAQ 1: What is the primary purpose of a neutral benchmarking study in computational biology? A neutral benchmarking study aims to provide a systematic, unbiased comparison of different computational methods to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate tool for their specific analytical tasks and data types. Unlike benchmarks conducted by method developers to showcase their own tools, neutral studies focus on comprehensive evaluation without favoring any particular method, thereby offering the community trustworthy performance assessments [1].

FAQ 2: What are the common challenges when selecting a gold standard dataset for benchmarking? A major challenge is the lack of consensus on what constitutes a gold standard dataset for many applications. Key issues include determining the minimum number of samples, adequate data coverage and fidelity, and whether molecular confirmation is needed. Furthermore, generating experimental gold standards is complex and labor-intensive. While simulated data offers a known ground truth, it may not fully capture the complexity and variability of real biological data [19] [1].

FAQ 3: How can I avoid the "self-assessment trap" in benchmarking? The "self-assessment trap" refers to the potential bias introduced when developers evaluate their own tools. To avoid this, strive for neutrality by being equally familiar with all methods being benchmarked or by involving the original method authors to ensure each tool is evaluated under optimal conditions. It is also critical to avoid practices like extensively tuning parameters for a new method while using only default parameters for competing methods [19] [1].

FAQ 4: What should I do if a computational tool is too difficult to install or run? Document these instances in a log file. This documentation saves time for other researchers and provides valuable context for the practical usability of computational tools, which is an important aspect of method selection. Including only tools that can be successfully installed and run after a reasonable amount of troubleshooting is a valid inclusion criterion [19].

FAQ 5: Why is parameter optimization important in a benchmarking study? Parameter optimization is crucial because the performance of a computational method can be highly sensitive to its parameter settings. To ensure a fair comparison, the optimal parameters for each tool and given dataset should be identified and used. In a competition-based benchmark, participants handle this themselves. In an independent study, the benchmarkers need to test different parameter combinations to find the best-performing setup for each algorithm [19].

Troubleshooting Common Benchmarking Issues

Issue 1: Incomplete or Non-Reproducible Code from Publications

- Problem: You cannot reproduce the results of a published tool due to missing code, data, or incomplete documentation.

- Solution: Focus on a representative subset of tools for which code and data can be reliably obtained and adapted. When developing new methods, ensure all code, data, and parameters are thoroughly documented and shared in a structured manner, such as using containerized environments (e.g., Docker) to encapsulate all dependencies [5] [19].

Issue 2: Overly Simplistic Simulations Skewing Results

- Problem: Benchmarking results derived from simulated data do not align with performance on real experimental data.

- Solution: Validate simulated data by ensuring it accurately reflects key properties of real data. Use empirical summaries (e.g., dropout profiles for single-cell RNA-seq, error profiles for sequencing data) to compare simulated and real datasets. Whenever possible, complement benchmarking with experimental datasets to assess performance under real-world conditions [1].

Issue 3: Selecting Appropriate Performance Metrics

- Problem: The chosen evaluation metrics do not align with the biological question, leading to misleading conclusions.

- Solution: Carefully select metrics that are relevant to the biological task. Move beyond standard machine learning metrics by designing evaluations tied to open questions in biology, such as gene regulation. Package the evaluation scripts for community reuse [19] [5].

Experimental Protocols for Key Benchmarking Steps

Protocol 1: Designing a Benchmarking Study with a Balanced Dataset Collection

Objective: To construct a robust set of reference datasets that provides a comprehensive evaluation of computational methods under diverse conditions.

Methodology:

- Integrate Data Types: Combine both simulated and real experimental datasets.

- Simulated Data Generation: Use models that introduce a known ground truth (e.g., spiked-in synthetic RNA, known differential expression) and validate that the simulations mirror empirical properties of real data.

- Experimental Data Curation: Source publicly available datasets. When a ground truth is unavailable, use accepted alternatives such as:

- Variety and Scope: Include datasets with varying levels of complexity, coverage, and from different biological conditions to test the generalizability and robustness of the methods.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Containerized Workflow for Reproducibility

Objective: To ensure that all benchmarked tools run in an identical, reproducible software environment across different computing platforms.

Methodology:

- Containerization: Package each computational tool and its dependencies into a container (e.g., using Docker).

- Dependency Management: Document all software dependencies, library versions, and system requirements within the container configuration file.

- Command Standardization: Record the exact commands, parameters, and input pre-processing steps used for each tool in a centralized spreadsheet.

- Output Standardization: Develop and share scripts to convert the output of each tool into a universal format, facilitating fair and consistent comparison using the same evaluation metrics [19].

Performance Metrics and Data Tables

Table 1: Common Performance Metrics for Computational Genomics Tool Benchmarking

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Primary Use Case | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Accuracy | Precision, Recall, F1-Score | Evaluating variant calling, feature selection | Measures a tool's ability to correctly identify true positives while minimizing false positives and false negatives. |

| Statistical Power | AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) | Differential expression analysis, binary classification | Assesses the ability to distinguish between classes across all classification thresholds. |

| Effect Size & Agreement | Correlation Coefficients (e.g., Pearson, Spearman) | Comparing expression estimates, epigenetic modifications | Quantifies the strength and direction of the relationship between a tool's output and a reference. |

| Scalability & Efficiency | CPU Time, Peak Memory Usage | Assessing practical utility on large datasets | Measures computational resource consumption, critical for large-scale omics data. |

| Reproducibility & Stability | Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Replicate analysis, cluster stability | Evaluates the consistency of results under slightly varying conditions or across replicates. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for a Benchmarking Toolkit

| Resource | Function in Benchmarking | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard Datasets | Serves as ground truth for evaluating tool accuracy. | Can be experimental (e.g., Sanger sequencing, spiked-in controls) or carefully validated simulated data [19] [1]. |

| Containerization Software (e.g., Docker) | Packages tools and dependencies into a portable, reproducible computing environment [19]. | Ensures consistent execution across different operating systems and hardware. |

| Version-Controlled Code Repository (e.g., Git) | Manages scripts for simulation, tool execution, and metric calculation. | Essential for tracking changes, collaborating, and ensuring the provenance of the analysis. |

| Public Data Repositories (e.g., NMDC, SRA) | Sources of real experimental data for benchmarking and validation [20]. | Provide diverse, large-scale datasets to test tool performance under real-world conditions. |

| Computational Platforms (e.g., KBase) | Integrated platforms for data analysis and sharing computational workflows [20]. | Promote transparency and allow other researchers to reproduce and build upon the benchmarking study. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Benchmarking Workflow

Data Strategy

A Landscape of Tools and Their Real-World Applications

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and foundational knowledge for researchers working at the intersection of next-generation sequencing (NGS), CRISPR genome editing, and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML). The content is framed within a broader thesis on benchmarking functional genomics computational tools.

NGS Platform Troubleshooting

Next-Generation Sequencing is the foundation of modern genomic data acquisition. The table below summarizes common experimental issues and their solutions [21] [22].

Table: Troubleshooting Common NGS Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low sequencing data yield | Inadequate library concentration, cluster generation failure, flow cell issues | Quantify library using fluorometry; verify cluster optimization; inspect flow cell quality control reports | Perform accurate library quantification; calibrate sequencing instrument regularly |

| High duplicate read rate | Insufficient input DNA, over-amplification during PCR, low library complexity | Increase input DNA; optimize PCR cycles; use amplification-free library prep kits | Use sufficient starting material (≥50 ng); normalize libraries before sequencing |

| Poor base quality scores (Q-score <30) | Signal intensity decay over cycles, phasing/pre-phasing issues, reagent degradation | Monitor quality metrics in real-time (Illumina); clean optics; use fresh sequencing reagents | Perform regular instrument maintenance; store reagents properly; use appropriate cycle numbers |

| Sequence-specific bias | GC-content extremes, repetitive regions, secondary structures | Use PCR additives; fragment DNA to optimal size; employ matched normalization controls | Check GC-content of target regions; use specialized kits for extreme GC regions |

| Low alignment rate | Sample contamination, adapter sequence presence, poor read quality, reference genome mismatch | Screen for contaminants; trim adapter sequences; perform quality filtering; verify reference genome version and assembly | Use quality control (QC) tools (FastQC) pre-alignment; select appropriate reference genome |

NGS Experimental Protocol: Standard RNA-Seq Workflow

Objective: Transcriptome profiling for differential gene expression analysis. Applications: Disease biomarker discovery, drug response studies, developmental biology [21].

Methodology:

- RNA Extraction & QC: Isolate total RNA using silica-column or magnetic bead-based methods. Assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥8.0 using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation.

- Library Preparation:

- Deplete ribosomal RNA or enrich poly-A tails to isolate mRNA.

- Fragment RNA to 200-300 base pairs.

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

- Ligate platform-specific adapters and sample barcodes (indexes).

- Amplify library with 10-15 PCR cycles.

- Library QC & Normalization: Quantify with Qubit fluorometer. Validate fragment size distribution (Bioanalyzer). Pool libraries at equimolar concentrations.

- Sequencing: Load normalized pool onto sequencer (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq X). Use paired-end sequencing (2x150 bp) for >80 million reads per sample.

- Data Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to samples using barcode information.

- QC & Trimming: Use FastQC for quality check and Trimmomatic to remove adapters/low-quality bases.

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome/transcriptome using STAR or HISAT2 aligners.

- Quantification: Generate counts per gene using featureCounts or HTSeq.

- Differential Expression: Analyze with DESeq2 or edgeR in R.

NGS RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

NGS Platform FAQs

Q1: Our NGS data shows high duplication rates. How can we improve library complexity for future experiments? A1: High duplication rates often stem from insufficient starting material or over-amplification. To improve complexity: increase input DNA/RNA to manufacturer's recommended levels (e.g., 50-1000 ng for WGS); reduce PCR cycles during library prep; consider using PCR-free protocols for DNA sequencing; and accurately quantify material with fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than spectrophotometry [22].

Q2: What are the critical quality control checkpoints in an NGS workflow? A2: Implement QC at these critical points: (1) Sample Input: Assess RNA/DNA quality (RIN >8, DIN >7); (2) Post-Library Prep: Verify fragment size distribution and concentration; (3) Pre-Sequencing: Confirm molarity of pooled libraries; (4) Post-Sequencing: Review Q-scores, alignment rates, and duplication metrics using MultiQC. Always include a positive control sample when possible [21] [22].

Q3: How do we choose between short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Nanopore, PacBio) sequencing platforms? A3: Platform choice depends on application. Use short-reads for: variant discovery, transcript quantification, targeted panels, and ChIP-seq where high accuracy and depth are needed. Choose long-reads for: genome assembly, structural variant detection, isoform sequencing, and resolving repetitive regions, as they provide greater contiguity. Hybrid approaches often provide the most comprehensive view [21].

CRISPR Experiment Troubleshooting

CRISPR genome editing faces challenges with efficiency and specificity. The table below outlines common issues encountered in CRISPR experiments [23] [24].

Table: Troubleshooting Common CRISPR Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | Poor gRNA design, inefficient delivery, low Cas9 expression, difficult-to-edit cell type, chromatin accessibility | Use AI-designed gRNAs (DeepCRISPR); optimize delivery method; validate Cas9 activity; use chromatin-modulating agents | Select gRNAs with high predicted efficiency scores; use validated positive controls; choose optimal cell type |

| High off-target effects | gRNA sequence similarity to non-target sites, high Cas9 expression, prolonged expression | Use AI prediction tools (CRISPR-M); employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants (eSpCas9); optimize delivery to limit exposure time; use ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery | Design gRNAs with minimal off-target potential; use modified Cas9 versions; titrate delivery amount |

| Cell toxicity | Excessive DNA damage, high off-target activity, innate immune activation, delivery method toxicity | Switch to milder editors (base/prime editing); reduce Cas9/gRNA amount; use RNP delivery; test different delivery methods (LNP vs. virus) | Titrate editing components; use control to distinguish delivery vs. editing toxicity; consider cell health indicators |

| Inefficient homology-directed repair (HDR) | Dominant NHEJ pathway, cell cycle status, insufficient donor template, poor HDR design | Synchronize cells in S/G2 phase; use NHEJ inhibitors; optimize donor design and concentration; use single-stranded DNA donors; employ Cas9 nickases | Increase donor template amount; use chemical enhancers (RS-1); validate HDR donors with proper homology arms |

| Variable editing across cell populations | Inefficient delivery, mixed cell states, transcriptional silencing | Use FACS to isolate successfully transfected cells; employ reporter systems; optimize delivery for specific cell type; use constitutive promoters | Use uniform cell population (synchronize if needed); employ high-efficiency delivery (nucleofection); use validated delivery protocols |

CRISPR Experimental Protocol: Mammalian Cell Gene Knockout

Objective: Generate functional gene knockouts in mammalian cells via CRISPR-Cas9 induced indels. Applications: Functional gene validation, disease modeling, drug target identification [25] [24].

Methodology:

- gRNA Design:

- Use AI-powered tools (CRISPR-GPT, DeepCRISPR) to design 3-5 gRNAs targeting early coding exons.

- Select gRNAs with >80% predicted efficiency and <0.2 off-target score.

- Include a positive control gRNA (e.g., targeting a known essential gene).

- Construct Preparation:

- Clone gRNAs into Cas9 expression plasmid (e.g., lentiCRISPRv2).

- Verify sequences by Sanger sequencing.

- Alternatively, synthesize chemically modified sgRNAs for RNP formation.

- Cell Transfection:

- Seed 2x10^5 cells/well in 12-well plate 24h pre-transfection.

- For plasmids: Use lipofectamine 3000 with 1 µg plasmid DNA.

- For RNP: Complex 2 µg Alt-R S.p. Cas9 nuclease with 1 µg synthetic gRNA, deliver via nucleofection.

- Validation & Screening:

- 72h post-transfection: Harvest genomic DNA using silica-column method.

- Perform T7 Endonuclease I assay or Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) analysis to assess editing efficiency.

- Day 7-14: Single-cell clone isolation via limiting dilution. Expand clones for 2-3 weeks.

- Screen clones by PCR + Sanger sequencing of target region.

- Confirm protein knockout by Western blot (if antibody available).

CRISPR Gene Knockout Workflow

CRISPR Platform FAQs

Q1: Despite good gRNA predictions, our editing efficiency remains low. What factors should we investigate? A1: If gRNA design is optimal, investigate: (1) Delivery efficiency - measure Cas9-GFP expression or use flow cytometry to quantify delivery rates; (2) Cell health - ensure >90% viability pre-transfection; (3) gRNA formatting - verify U6 promoter expression and gRNA scaffold integrity; (4) Chromatin accessibility - check ATAC-seq or histone modification data for target region; (5) Cas9 activity - test with positive control gRNA. Consider switching to high-efficiency systems like Cas12a if Cas9 fails [24].

Q2: What strategies are most effective for minimizing off-target effects in therapeutic applications? A2: Implement a multi-layered approach: (1) Computational design - use AI tools (CRISPR-M, DeepCRISPR) that integrate epigenetic and sequence context; (2) High-fidelity enzymes - use eSpCas9(1.1) or SpCas9-HF1 variants; (3) Delivery optimization - use RNP complexes with short cellular exposure instead of plasmid DNA; (4) Dosage control - titrate to lowest effective concentration; (5) Comprehensive assessment - validate with GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq methods pre-clinically [23] [24].

Q3: How does AI actually improve CRISPR experiment design compared to traditional methods? A3: AI transforms CRISPR design by: (1) Pattern recognition - identifying subtle sequence features affecting gRNA efficiency beyond simple rules; (2) Multi-modal integration - combining epigenetic, structural, and cellular context data; (3) Predictive accuracy - achieving >95% prediction accuracy for editing outcomes in some applications; (4) Novel system design - generating entirely new CRISPR proteins (e.g., OpenCRISPR-1) with improved properties; (5) Automation - systems like CRISPR-GPT can automate experimental planning from start to finish [23] [25] [26].

AI/ML Platform Troubleshooting

AI/ML platforms face unique challenges in genomic applications. The table below outlines common issues and solutions [22] [27].

Table: Troubleshooting Common AI/ML Platform Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor model generalizability (works on training but not validation data) | Overfitting, biased training data, dataset shift, inadequate feature selection | Increase training data; apply regularization; use cross-validation; perform data augmentation; balance dataset classes | Collect diverse, representative data; use simpler models; implement feature selection; validate on external datasets |

| Long training times | Large model complexity, insufficient computational resources, inefficient data pipelines, suboptimal hyperparameters | Use distributed training; leverage GPU acceleration (NVIDIA Parabricks); optimize data loading; implement early stopping; use cloud computing (AWS, Google Cloud) | Start with pretrained models; use appropriate hardware; profile code bottlenecks; set up efficient data preprocessing |

| Difficulty interpreting model predictions ("black box" problem) | Complex deep learning architectures, lack of explainability measures | Use SHAP or LIME for interpretability; switch to simpler models when possible; incorporate attention mechanisms; generate feature importance scores | Choose interpretable models by default; build in explainability from start; use visualization tools; document prediction confidence |

| Data quality issues | Missing values, batch effects, inconsistent labeling, noisy biological data | Implement rigorous data preprocessing; remove batch effects (ComBat); use imputation techniques; employ data augmentation; establish labeling protocols | Standardize data collection; use controlled vocabularies; implement data versioning; perform exploratory data analysis before modeling |

| Integration challenges with existing workflows | Incompatible data formats, API limitations, computational resource constraints, skill gaps | Use containerization (Docker); develop standardized APIs; create wrapper scripts; utilize cloud solutions; provide team training | Plan integration early; choose platforms with good documentation; pilot test on small scale; involve computational biologists in experimental design |

AI/ML Experimental Protocol: Variant Calling Analysis with DeepVariant

Objective: Accurately identify genetic variants (SNPs, indels) from NGS data using deep learning. Applications: Disease variant discovery, population genetics, cancer genomics [22] [27].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Input: Sequence Alignment Map (BAM/CRAM) files and reference genome (FASTA).

- Preprocess: Ensure proper read alignment, duplicate marking, and base quality score recalibration.

- Split data: 80% for training, 10% for validation, 10% for testing.

- Model Configuration:

- Use DeepVariant (CNN architecture) which creates images from sequencing data.

- Configure input parameters: read length, sequencing technology (Illumina, PacBio), ploidy.

- For custom training: Prepare truth variant calls (VCF) from validated datasets.

- Variant Calling:

- Run inference on test data:

run_deepvariant --model_type=WGS --ref=reference.fasta --reads=input.bam --output_vcf=output.vcf - For large datasets: Use GPU acceleration (NVIDIA Parabricks) for 10-50x speed improvement.

- Run inference on test data:

- Validation & Benchmarking:

- Compare against ground truth using hap.py for precision/recall metrics.

- Validate novel variants by Sanger sequencing (random subset of 20-30 variants).

- Benchmark against GATK pipeline for sensitivity/specificity comparison.

AI-Based Variant Calling Workflow

AI/ML Platform FAQs

Q1: What are the key considerations when selecting an AI tool for genomic analysis? A1: Consider: (1) Accuracy - benchmark against gold standards (e.g., GIAB for variant calling); (2) Dataset compatibility - ensure support for your sequencing type and organisms; (3) Computational requirements - assess GPU/CPU needs and cloud vs. on-premise deployment; (4) Regulatory compliance - for clinical use, verify HIPAA/GxP compliance (e.g., DNAnexus Titan); (5) Integration support - check for APIs and workflow management features; (6) Scalability - evaluate performance on large cohort sizes [27].

Q2: How much training data is typically needed to develop accurate genomic AI models? A2: Requirements vary by task: (1) Variant calling - models like DeepVariant benefit from thousands of genomes with validated variants; (2) gRNA efficiency - tools like DeepCRISPR were trained on 10,000+ gRNAs with measured activities; (3) Clinical prediction - typically requires hundreds to thousands of labeled cases. For custom models, start with at least 100-500 positive examples per class. Transfer learning from pre-trained models can reduce data needs by up to 80% for related tasks [22] [23].

Q3: Our institution has limited computational resources. What are the most resource-efficient options for implementing AI in genomics? A3: Several strategies maximize efficiency: (1) Cloud-based solutions - use Google Cloud Genomics or AWS with spot instances to minimize costs; (2) Pre-trained models - leverage models like DeepVariant without retraining; (3) Web-based platforms - use Benchling or CRISPR-GPT that require no local infrastructure; (4) Hybrid approaches - do preprocessing locally and intensive training in cloud; (5) Optimized tools - select tools with hardware acceleration (NVIDIA Parabricks for GPU, DRAGEN for FPGA). Start with free tools like DeepVariant before investing in commercial platforms [27].

Integrated Workflow: NGS + CRISPR + AI/ML

Modern functional genomics increasingly combines NGS, CRISPR, and AI/ML in integrated workflows. The diagram below illustrates how these technologies interconnect in a typical functional genomics pipeline [21] [22] [23].

Integrated Functional Genomics Workflow

Integrated Experimental Protocol: AI-Guided Functional Genomics Screen

Objective: Identify and validate novel disease genes through integrated NGS, CRISPR, and AI analysis. Applications: Drug target discovery, disease mechanism elucidation, biomarker identification [25] [24].

Methodology:

Target Identification Phase:

- NGS Component: Perform whole genome/exome sequencing of patient cohorts and controls.

- AI Component: Use DeepVariant for variant calling; train ML models to prioritize pathogenic variants; integrate multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) using neural networks.

- Output: Rank-ordered list of candidate genes with predicted functional impact.

Experimental Design Phase:

- AI Component: Input candidate genes into CRISPR-GPT for automated experimental planning.

- Output: Complete experimental workflow including: gRNA designs (3-5 per gene), appropriate CRISPR modality (knockout, activation, base editing), delivery method recommendations, and validation assays.

Functional Validation Phase:

- CRISPR Component: Execute pooled or arrayed CRISPR screens in relevant cellular models.

- NGS Component: Pre-screen baseline transcriptome (RNA-seq) and post-screen phenotyping (single-cell RNA-seq or targeted sequencing).

- Quality Control: Include positive/negative controls; assess editing efficiency by NGS of target sites.

Integrative Analysis Phase:

- AI Component: Apply ML models to identify hit genes whose perturbation produces disease-relevant phenotypes.

- Validation: Confirm top hits in orthogonal models (primary cells, organoids).

- Multi-omics Integration: Combine CRISPR screening data with original patient NGS data to establish clinical relevance.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential research reagents and computational tools for functional genomics experiments integrating NGS, CRISPR, and AI/ML platforms [27] [25] [24].

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function | Example Products/Tools | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Wet Lab | Library Prep Kits | Convert nucleic acids to sequencer-compatible libraries | Illumina DNA Prep; KAPA HyperPrep; NEBNext Ultra II | Select based on input material, application, and desired yield |

| NGS Wet Lab | Sequencing Reagents | Provide enzymes, nucleotides, and buffers for sequencing-by-synthesis | Illumina SBS Chemistry; Nanopore R9/R10 flow cells | Match to platform; monitor lot-to-lot variability |

| NGS Analysis | Alignment Tools | Map sequencing reads to reference genomes | BWA-MEM; STAR (RNA-seq); Bowtie2 (ChIP-seq) | Optimize parameters for specific applications and read lengths |

| NGS Analysis | Variant Callers | Identify genetic variants from aligned reads | GATK; DeepVariant; FreeBayes | Choose based on variant type and sequencing technology |

| CRISPR Wet Lab | Cas Enzymes | RNA-guided nucleases for targeted DNA cleavage | Wild-type SpCas9; High-fidelity variants; Cas12a; AI-designed OpenCRISPR-1 | Select based on PAM requirements, specificity needs, and size constraints |

| CRISPR Wet Lab | gRNA Synthesis | Produce guide RNAs for targeting Cas enzymes | Chemical synthesis (IDT); Plasmid-based expression; in vitro transcription | Chemical modification can enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity |

| CRISPR Wet Lab | Delivery Systems | Introduce CRISPR components into cells | Lipofectamine; Nucleofection; Lentivirus; AAV; Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Choose based on cell type, efficiency requirements, and safety considerations |

| CRISPR Analysis | gRNA Design Tools | Predict efficient gRNAs with minimal off-target effects | CRISPR-GPT; DeepCRISPR; CRISPOR; CHOPCHOP | AI-powered tools generally outperform traditional algorithms |

| CRISPR Analysis | Off-Target Assessment | Identify and quantify unintended editing sites | GUIDE-seq; CIRCLE-seq; CRISPResso2; AI prediction tools (CRISPR-M) | Use complementary methods for comprehensive assessment |

| AI/ML Platforms | Variant Analysis | Accurately call and interpret genetic variants using deep learning | DeepVariant; NVIDIA Clara Parabricks; Illumina DRAGEN | GPU acceleration significantly improves processing speed for large datasets |

| AI/ML Platforms | Multi-Omics Integration | Combine and analyze multiple data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) | DNAnexus Titan; Seven Bridges; Benchling R&D Cloud | Ensure platform supports required data types and analysis workflows |

| AI/ML Platforms | Automated Experimentation | Plan and optimize biological experiments using AI | CRISPR-GPT; Benchling AI tools; Synthace | Particularly valuable for complex experimental designs and novice researchers |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Sequencing Platform Troubleshooting

Q: How to troubleshoot MiSeq runs taking longer than usual or expected? A: Extended run times can be caused by various instrument issues. Consult the manufacturer's troubleshooting guide for specific error messages and recommended actions, which may include checking fluidics systems, flow cells, or software configurations [28].

Q: What are the best practices to avoid low cluster density on the MiSeq? A: Low cluster density can significantly impact data quality. Ensure proper library quantification and normalization, and verify the integrity of all reagents. Follow the manufacturer's established best practices for library preparation and loading [28].

Q: How to troubleshoot elevated PhiX alignment in sequencing runs? A: Elevated PhiX alignment often indicates issues with the library preparation. This can be due to adapter dimers, low library diversity, or insufficient quantity of the target library. Review library QC steps and ensure proper removal of adapter dimers before sequencing [29].

Computational Tool FAQs

Q: What is the primary difference between DNABERT-2 and Nucleotide Transformer? A: The primary differences lie in their tokenization strategies, architectural choices, and training data. DNABERT-2 uses Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) for tokenization and incorporates Attention with Linear Biases (ALiBi) to handle long sequences efficiently [30] [31]. Nucleotide Transformer employs non-overlapping k-mer tokenization (typically 6-mers) and rotary positional embeddings, and it is trained on a broader set of species [32] [33].

Q: I encounter memory errors when running DNABERT-2. What should I do? A: Try reducing the batch size of your input data. Also, ensure you have the latest versions of PyTorch and the Hugging Face Transformers library installed, as these may include optimizations that reduce memory footprint [34].

Q: Which foundation model is best for predicting epigenetic modifications? A: According to a comprehensive benchmarking study, Nucleotide Transformer version-2 (NT-v2) excels in tasks related to epigenetic modification detection, while DNABERT-2 shows the most consistent performance across a wider range of human genome-related tasks [32].

Q: How can I get started with the Nucleotide Transformer models? A: The pre-trained models and inference code are available on GitHub and Hugging Face. You can clone the repository, set up a Python virtual environment, install the required dependencies, and then load the models using the provided examples [35].

Performance Benchmarking Data

Table 1: Benchmarking Comparison of DNA Foundation Models

| Model | Primary Architecture | Tokenization Strategy | Training Data (Number of Species) | Optimal Embedding Method (AUC Improvement) | Key Benchmarking Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNABERT-2 | Transformer (BERT-like) | Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) | 135 [31] | Mean Token Embedding (+9.7%) [32] | Most consistent on human genome tasks [32] |

| Nucleotide Transformer v2 (NT-v2) | Transformer (BERT-like) | Non-overlapping 6-mers | 850 [32] | Mean Token Embedding (+4.3%) [32] | Excels in epigenetic modification detection [32] |

| HyenaDNA | Decoder-based with Hyena operators | Single Nucleotide | Human genome only [32] | Mean Token Embedding [32] | Best runtime & long sequence handling [32] |

Table 2: Model Configuration and Efficiency Metrics

| Model | Model Size (Parameters) | Output Embedding Dimension | Maximum Sequence Length | Relative GPU Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNABERT-2 | 117 million [32] | 768 [32] | No hard limit [32] | ~92x less than NT [30] |

| NT-v2-500M | 500 million [32] | 1024 [32] | 12,000 nucleotides [32] | Baseline for comparison |

| HyenaDNA-160K | ~30 million [32] | 256 [32] | 1 million nucleotides [32] | N/A |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Embeddings with DNABERT-2

Purpose: To obtain numerical representations (embeddings) of DNA sequences using the DNABERT-2 model for downstream genomic tasks.

Steps:

- Import Libraries: Ensure you have PyTorch and the Hugging Face Transformers library installed.

- Load Model and Tokenizer:

Tokenize DNA Sequence: Input your DNA sequence (e.g., "ACGTAGCATCGGATCTATCTATCGACACTTGGTTATCGATCTACGAGCATCTCGTTAGC") and convert it into tensors.

Extract Hidden States: Pass the tokenized input through the model to get the hidden states.

Generate Sequence Embedding (Mean Pooling): Summarize the token embeddings into a single sequence-level embedding by taking the mean across the sequence dimension.

Note: Benchmarking studies strongly recommend using mean token embedding over the default sentence-level summary token for better performance, with an average AUC improvement of 9.7% for DNABERT-2 [32].

Protocol 2: Zero-Shot Benchmarking of Foundation Model Embeddings

Purpose: To objectively evaluate the inherent quality of pre-trained model embeddings without the confounding factors introduced by fine-tuning.

Steps:

- Dataset Curation: Collect diverse genomic datasets with DNA sequences labeled for specific biological traits (e.g., 4mC site detection across multiple species) [32].

- Embedding Generation: For each model (DNABERT-2, NT-v2, HyenaDNA), generate embeddings for all sequences in the benchmark datasets using the mean token embedding method. Keep all model weights frozen (zero-shot) [32].

- Downstream Model Training: Use the generated embeddings as input features to efficient, simple machine learning models (e.g., tree-based models or small MLPs). This minimizes inductive bias and allows for a thorough hyperparameter search [32].

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the downstream models on held-out test sets using relevant metrics (e.g., AUC for classification tasks). Compare the performance across different DNA foundation models to assess their embedding quality [32].

Workflow Visualization

Foundation Model Analysis Workflow

Troubleshooting Decision Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Genomic Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNABERT-2 | Pre-trained Foundation Model | Generates context-aware embeddings from DNA sequences for tasks like regulatory element prediction. | Hugging Face: zhihan1996/DNABERT-2-117M [34] |

| Nucleotide Transformer (NT) | Pre-trained Foundation Model | Provides nucleotide representations for molecular phenotype prediction and variant effect prioritization. | GitHub: instadeepai/nucleotide-transformer [35] |

| GUE Benchmark | Standardized Benchmark Dataset | Evaluates and compares genome foundation models across multiple species and tasks. | GitHub: MAGICS-LAB/DNABERT_2 [30] |

| Hugging Face Transformers | Software Library | Provides the API to load, train, and run transformer models like DNABERT-2. | Python Package: pip install transformers [34] |

| PyTorch | Deep Learning Framework | Enables tensor computation and deep neural networks for model training and inference. | Python Package: pip install torch [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is specialized benchmarking crucial for AI-based target discovery platforms, and why aren't general-purpose LLMs sufficient?

Specialized benchmarking is essential because drug discovery requires disease-specific predictive models and standardized evaluation. General-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4o, Claude-Opus-4, and DeepSeek-R1 significantly underperform compared to purpose-built systems. For example, in head-to-head benchmarks, disease-specific models achieved a 71.6% clinical target retrieval rate, which is a 2–3x improvement over LLMs, which typically range between 15% and 40% [36]. Furthermore, LLMs struggle with key practical requirements, showing high levels of "AI hallucination" in genomics tasks and performing poorly when generating longer target lists [36] [37]. Dedicated benchmarks like TargetBench 1.0 and CARA are designed to evaluate models on biologically relevant tasks and real-world data distributions, which is critical for reliable application in early drug discovery [36] [38].

Q2: What are the most common pitfalls when benchmarking a new target identification method, and how can I avoid them?

Common pitfalls include using inappropriate data splits, non-standardized metrics, and failing to account for real-world data characteristics.

- Inadequate Data Splitting: Using random splits can lead to data leakage and over-optimistic performance, especially when similar compounds are in both training and test sets. Instead, use temporal splits (based on approval dates) or design splits that separate congeneric compounds (common in lead optimization) from diverse compound libraries (common in virtual screening) [39] [38].

- Ignoring Data Source Bias: Public data often has biased protein exposure, where a few well-studied targets dominate the data. Benchmarking should account for this to ensure models generalize to less-studied targets [38].

- Using Irrelevant Metrics: Relying solely on metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC) can be misleading. Complement them with interpretable metrics like recall, precision, and accuracy at specific, biologically relevant thresholds [39].

Q3: My model performs well on public datasets but fails in internal validation. What could be the reason?

This is a classic sign of overfitting to the characteristics of public benchmark datasets, which may not mirror the sparse, unbalanced, and multi-source data found in real-world industrial settings [38]. The performance of models can be correlated with factors like the number of known drugs per indication and the chemical similarity within an indication [39]. To improve real-world applicability:

- Use benchmarks like CARA or EasyGeSe that are specifically curated from diverse real-world assays and multiple species [38] [6].

- Employ benchmarking frameworks like TargetBench that standardize evaluation across different models and datasets, providing a more reliable measure of translational potential [36].

- Ensure your internal data is used in a hold-out test set during development to simulate real-world performance from the beginning.

Q4: How can I assess the "druggability" and translational potential of novel targets predicted by my model?

Beyond mere prediction accuracy, a translatable target should have certain supporting evidence. When Insilico Medicine's TargetPro identifies novel targets, it evaluates them on several practical criteria, which you can adopt [36]:

- Structure Availability: 95.7% of its novel targets had resolved 3D protein structures, which is crucial for structure-based drug design.

- Druggability: 86.5% were classified as druggable, meaning they possess binding pockets or other properties that make them amenable to modulation by small molecules or biologics.

- Repurposing Potential: 46% overlapped with approved drugs for other indications, providing de-risking evidence from human pharmacology.

- Experimental Readiness: Nominated targets had, on average, over 500 associated bioassay datasets published, which is 1.4 times higher than competing systems, facilitating faster experimental validation.

Performance Benchmarking Tables

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of AI Target Identification Platforms

This table compares the performance of various platforms on key metrics for target identification, highlighting the superiority of disease-specific AI models. [36]

| Platform / Model | Clinical Target Retrieval Rate | Novel Targets: Structure Availability | Novel Targets: Druggability | Novel Targets: Repurposing Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TargetPro (AI, Disease-Specific) | 71.6% | 95.7% | 86.5% | 46.0% |

| LLMs (GPT-4o, Claude, etc.) | 15% - 40% | 60% - 91% | 39% - 70% | Significantly Lower |

| Open Targets (Public Platform) | ~20% | Information Not Available | Information Not Available | Information Not Available |

Table 2: Performance of Compound Activity Prediction Models on the CARA Benchmark

This table summarizes the performance of different model types on the CARA benchmark for real-world compound activity prediction tasks (VS: Virtual Screening, LO: Lead Optimization). [38]

| Model Type / Training Strategy | Virtual Screening (VS) Assays | Lead Optimization (LO) Assays | Key Findings & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|