Comparative Functional Genomics Study Design: Principles, Methods, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to designing effective comparative functional genomics studies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Functional Genomics Study Design: Principles, Methods, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to designing effective comparative functional genomics studies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from defining core concepts and selecting model systems to leveraging public genomic databases. The guide details modern methodological approaches, including high-throughput sequencing workflows, CRISPR-Cas9 for functional validation, and computational tools for data integration. It addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, such as managing batch effects and ensuring reproducibility, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks through experimental follow-up and multi-omics correlation. By synthesizing these four intents, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to generate robust, interpretable, and clinically relevant insights from genomic data.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Exploratory Frameworks in Comparative Functional Genomics

Comparative genomics and functional genomics are two pivotal, interconnected disciplines that have revolutionized modern biological research and therapeutic development. Comparative genomics involves the systematic comparison of genomic features across different species or strains to understand evolutionary processes, identify conserved elements, and annotate functional regions. By aligning and analyzing genomes from diverse organisms, researchers can pinpoint genetic sequences fundamental to life and those responsible for species-specific adaptations. Functional genomics, in contrast, focuses on determining the biological functions of genes and non-coding elements on a genome-wide scale, moving beyond sequence analysis to explore dynamic molecular processes such as gene expression, regulation, and protein function. Together, these fields form the cornerstone of a comprehensive approach to understanding the relationship between genetic information and phenotypic expression, providing critical insights for disease mechanism research and drug discovery.

The integration of these domains has become increasingly important in the context of complex disease research and personalized medicine. For drug development professionals, understanding the scope and objectives of these fields is essential for identifying novel therapeutic targets, understanding drug mechanisms, and predicting treatment responses across diverse populations. This guide delineates the distinct yet complementary roles of comparative and functional genomics, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to contemporary research.

Field Definitions and Core Objectives

Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomics is founded on the principle that comparing genomic sequences across evolutionary lineages can reveal fundamental biological insights. The primary scope involves analyzing similarities and differences in genome structure, organization, and content across species, strains, or individuals. This field leverages evolutionary relationships to infer function through conservation patterns and identify genetic elements underlying specific phenotypes.

Key objectives include:

- Identifying evolutionarily conserved elements: Genomic sequences preserved across species often indicate functional importance, enabling the discovery of regulatory regions and non-coding RNAs that may be difficult to identify through other methods.

- Understanding evolutionary relationships and mechanisms: Comparative analyses reveal how genomes evolve through processes like gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer, and chromosomal rearrangement, providing insights into speciation and adaptation.

- Annotating genomes and predicting gene function: By transferring functional annotations from well-characterized organisms to less-studied species, researchers can rapidly generate hypotheses about gene function in non-model organisms.

- Linking genetic variation to phenotypic differences: Comparing genomes of organisms with divergent traits helps identify genetic variants responsible for disease susceptibility, morphological diversity, and physiological adaptations.

Functional Genomics

Functional genomics aims to characterize the functional elements of genomes and their dynamic activities across different biological conditions. Rather than focusing solely on sequence information, this field investigates how genomic components operate and interact within cellular systems.

Key objectives include:

- Cataloging functional elements: Systematically identifying all coding genes, non-coding RNAs, regulatory regions, and structural elements within genomes.

- Deciphering gene regulation networks: Mapping the complex interactions between transcription factors, regulatory sequences, and epigenetic modifications that control spatial and temporal gene expression patterns.

- Characterizing biological pathways: Elucidating how genes and their products interact within metabolic, signaling, and regulatory pathways to execute cellular processes.

- Linking genetic variation to molecular phenotypes: Understanding how sequence variants affect gene expression, protein function, and ultimately cellular and organismal traits, particularly in disease contexts.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Designs

Core Technologies and Workflows

Both comparative and functional genomics employ diverse technological platforms to address their specific research questions. The experimental design must be carefully tailored to the specific objectives, with proper consideration of technical and biological replicates, controls, and analytical approaches.

Table 1: Key Methodologies in Comparative and Functional Genomics

| Field | Primary Methods | Data Types Generated | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Genomics | Whole-genome sequencing, Multiple sequence alignment, Phylogenetic analysis, Synteny mapping, Molecular evolution analysis | Genome assemblies, Sequence alignments, Conservation scores, Phylogenetic trees, Selection pressure estimates | Evolutionary studies, Genome annotation, Regulatory element discovery, Species classification |

| Functional Genomics | RNA sequencing, Chromatin immunoprecipitation, CRISPR screens, Mass spectrometry, Spatial transcriptomics | Gene expression matrices, Protein-DNA interaction maps, Functional enrichment scores, Splicing profiles, Epigenetic marks | Pathway analysis, Drug target identification, Mechanism of action studies, Biomarker discovery |

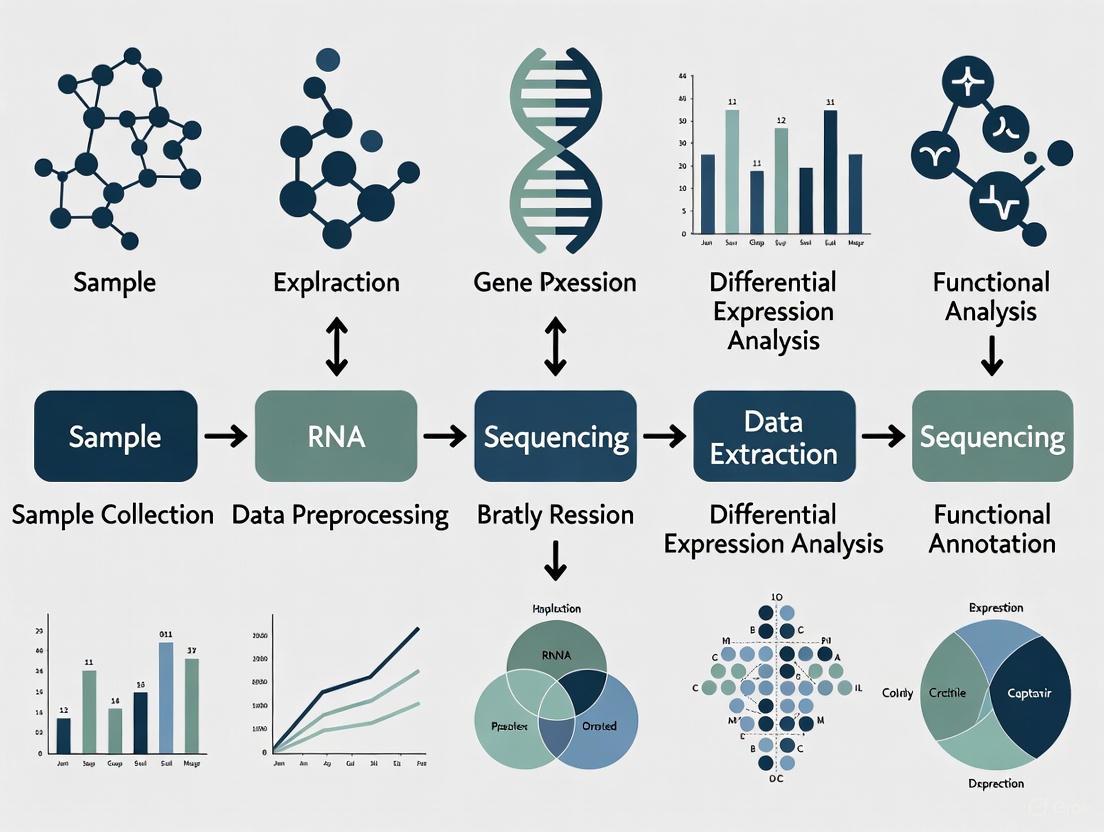

Diagram 1: Integrated workflows of comparative and functional genomics

Benchmarking Studies in Genomics

Robust benchmarking is essential for evaluating genomic methods. Recent studies have established comprehensive frameworks for assessing computational tools and experimental approaches across diverse biological contexts.

A 2025 benchmarking study evaluated 28 single-cell clustering algorithms on 10 paired transcriptomic and proteomic datasets, assessing performance through multiple metrics including Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), clustering accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness [1]. This systematic comparison revealed that methods like scAIDE, scDCC, and FlowSOM consistently demonstrated top performance across different omics data types, providing crucial guidance for researchers selecting analytical approaches for their specific applications.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Single-Cell Clustering Algorithms [1]

| Algorithm | Transcriptomic ARI (Mean) | Proteomic ARI (Mean) | Memory Efficiency | Time Efficiency | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scAIDE | 0.78 | 0.82 | Medium | Medium | Cross-modality integration |

| scDCC | 0.81 | 0.79 | High | Medium | Memory-constrained studies |

| FlowSOM | 0.76 | 0.80 | Medium | High | Large-scale datasets |

| CarDEC | 0.75 | 0.61 | Low | Low | Transcriptomics-specific |

| PARC | 0.73 | 0.58 | Medium | High | Rapid transcriptomic screening |

The importance of proper benchmarking methodologies is further emphasized by research highlighting that "the most truthful model for real data is real data," underscoring the need to validate methods using experimental datasets in addition to simulated data [2]. This is particularly relevant for drug development applications where analytical accuracy directly impacts target identification and validation.

Advanced Research Applications

Semantic Design in Functional Genomics

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have opened new possibilities for functional genomics research. The semantic design approach leverages genomic language models to generate novel functional sequences based on genomic context and known functional associations [3].

This methodology employs models like Evo, trained on prokaryotic genomic sequences, which learns the "distributional semantics" of gene function - the principle that "you shall know a gene by the company it keeps" [3]. By prompting the model with sequences of known function, researchers can generate novel genes enriched for targeted biological activities, effectively performing function-guided design beyond natural sequence space.

Experimental validation of this approach demonstrated its utility for generating functional multi-component systems. For type II toxin-antitoxin systems, semantic design generated novel toxic proteins and their corresponding antitoxins, with experimental validation confirming robust activity despite limited sequence similarity to natural proteins [3]. This methodology presents significant implications for drug discovery, enabling the generation of novel therapeutic proteins and regulatory elements not constrained by natural evolutionary histories.

Diagram 2: Semantic design workflow using genomic language models

Multi-Omics Integration in Complex Disease Research

The integration of comparative and functional genomics approaches is particularly powerful in studying complex human diseases. Multi-omics studies combine genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data to unravel disease mechanisms from multiple molecular perspectives.

In perinatal depression research, functional genomics approaches have identified distinctive gene expression signatures and epigenetic modifications associated with the disorder [4]. Studies examining peripheral blood samples have revealed dysregulation in biological processes including oxytocin signaling, glucocorticoid response, estrogen signaling, and immune function, providing insights into potential mechanistic pathways and biomarker candidates.

The Cell Village experimental platform represents an innovative approach that combines elements of both comparative and functional genomics [5]. This method involves co-culturing genetically diverse cell lines in a shared environment, enabling population-scale genetic studies under controlled conditions. The platform facilitates investigation of genetic, molecular, and phenotypic heterogeneity, streamlining the process from variant identification to mechanistic insight for applications in QTL mapping, pharmacogenomics, and functional phenotyping.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful genomics research requires carefully selected reagents and computational tools tailored to specific experimental designs. The following toolkit represents essential resources for contemporary comparative and functional genomics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Genomics Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Long-read sequencers, Single-cell RNA-seq, CITE-seq, ECCITE-seq | Generate molecular profiling data | Transcriptome assembly, Multi-omics profiling, Epigenetic analysis |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR libraries, Prime editing, Growth inhibition assays | Confirm gene function | Target validation, Functional screening, Mechanism studies |

| Computational Tools | Evo genomic language model, Clustering algorithms, Genome browsers | Data analysis and interpretation | Sequence generation, Cell type identification, Genomic visualization |

| Data Resources | SynGenome, EasyGeSe, SPDB | Provide reference datasets | Method benchmarking, Model training, Comparative analysis |

| Integration Platforms | moETM, sciPENN, totalVI, JUMAP | Combine multi-omics data | Data integration, Dimension reduction, Pattern discovery |

Comparative and functional genomics represent complementary approaches to unraveling the complexity of biological systems. While comparative genomics provides evolutionary context and identifies functionally important elements through conservation patterns, functional genomics characterizes the dynamic activities of these elements across diverse biological conditions. The integration of these fields, particularly through multi-omics approaches and advanced computational methods like semantic design, continues to drive innovations in basic research and therapeutic development.

For drug development professionals, understanding the scope, objectives, and methodologies of these fields is crucial for leveraging genomic information in target identification, mechanism elucidation, and biomarker discovery. The ongoing development of benchmarking resources and standardized evaluation protocols will further enhance the reliability and translational potential of genomic research, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for complex diseases.

Selecting Appropriate Model Organisms and Experimental Systems

The field of comparative functional genomics relies on selecting appropriate model organisms and experimental systems to unravel gene function and its impact on phenotype. This selection process requires careful consideration of biological similarities, practical handling, and specific research applications. With advances in genomic technologies and high-throughput screening methods, researchers now have an expanded toolkit for functional genomics studies. This guide provides an objective comparison of model organisms and experimental systems, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform research design in drug development and basic biological research.

Comparative Analysis of Model Organisms

The table below summarizes key model organisms used in functional genomics research, their distinctive advantages, and primary research applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Model Organisms for Functional Genomics

| Organism | Key Advantages | Research Applications | Technical Features | Genetic Tools Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | External embryo development, translucent embryos, high fecundity | Developmental studies, cellular mechanisms, disease modeling [6] | Biallelic gene disruption possible; 99% success rate for CRISPR mutagenesis; 28% average germline transmission rate [7] | CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, morpholinos [7] |

| Mouse | Close genetic similarity to humans, well-characterized physiology | Disease modeling, mammalian biology, therapeutic development [6] | CRISPR-Cas9 achieves 14-20% gene disruption efficiency in one-cell embryos [7] | CRISPR-Cas9, base editors, prime editors [7] |

| Pig | Similar organ size and physiology to humans | Xenotransplantation, immunology, regenerative medicine [6] | CRISPR used to modify multiple genes involved in immune rejection [6] | CRISPR-Cas9 for multi-gene editing [6] |

| Syrian Golden Hamster | Susceptible to human respiratory viruses, similar ACE2 proteins to humans | Respiratory virus studies, COVID-19 pathogenesis, vaccine development [6] | Excellent model for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis at systems and cellular levels [6] | Knock-out models for impeding adaptive immunity [6] |

| Killifish | Extremely short lifespan (4-6 months) among vertebrates | Aging research, lifespan studies, environmental adaptation [6] | One of shortest vertebrate lifespans; 22 aging-related genes identified including those for human progeria syndromes [6] | Comparative genomics for environmental adaptations [6] |

| Thirteen-Lined Ground Squirrel | Natural hibernation ability, metabolic flexibility | Metabolism studies, hibernation physiology, neuromuscular disorders [6] | Lowers body temperature to near freezing; switches metabolism from glucose to lipid-based [6] | Studies of nNOS enzyme localization during torpor [6] |

| Bats | Tolerant of viral infections, low cancer incidence, long lifespan | Viral reservoir studies, cancer resistance, immunology [6] | Reduced inflammatory response; lower NLRP3 inflammasome activation [6] | Comparative genomics of immune genes [6] |

High-Throughput Screening Technologies

High-throughput screening (HTS) technologies enable functional genomics at scale. The global HTS market is projected to grow from USD 26.12 billion in 2025 to USD 53.21 billion by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 10.7% [8]. The table below compares major HTS technology platforms.

Table 2: Comparison of High-Throughput Screening Technologies

| Technology Platform | Market Share (2025) | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assays | 33.4% [8] | Drug discovery, toxicity testing, functional genomics | Physiologically relevant data; insights into cellular processes | Higher complexity; more variables to control |

| Liquid Handling Systems | 49.3% (instruments segment) [8] | Sample preparation, assay assembly, compound screening | Automation of repetitive tasks; nanoliter-scale precision | High initial investment; requires technical expertise |

| CRISPR-based Screening | Emerging | Functional genomics, target identification, pathway analysis | High specificity; programmable; genome-wide capability | Off-target effects; delivery challenges in some systems |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | Growing | Cellular heterogeneity, transcriptomics, developmental biology | Single-cell resolution; reveals population diversity | Data sparsity; high per-cell cost |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics in Vertebrate Models

CRISPR-Cas technologies have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling precise genetic manipulations in various model organisms [7]. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for CRISPR-based screening:

Guide RNA Design: Design single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting genes of interest using established algorithms (20 nucleotide target sequence + NGG PAM sequence for S. pyogenes Cas9).

Library Construction: Clone sgRNAs into appropriate delivery vectors (lentiviral, plasmid). For large-scale screens, pooled libraries with 3-10 sgRNAs per gene are recommended.

Delivery System:

- In vitro: Transfect or transduce cells with CRISPR constructs.

- In vivo: Microinject CRISPR components into zygotes (mice, zebrafish).

Perturbation and Selection: Apply appropriate selection pressure (antibiotics, growth conditions) for 7-14 days to allow phenotypic manifestation.

Phenotypic Analysis:

- Sequencing-based readouts: Amplify and sequence genomic regions or barcodes.

- Imaging-based readouts: Use Cell Painting or morphological profiling.

- Functional assays: Measure proliferation, apoptosis, or pathway-specific reporters.

Data Analysis: Map sgRNA abundances to identify hits using specialized algorithms (MAGeCK, BAGEL).

This protocol has been successfully implemented in zebrafish to screen 254 genes for hair cell regeneration [7] and over 300 genes for retinal regeneration [7].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell CRISPRclean (scCLEAN) for Enhanced Transcriptome Profiling

The scCLEAN method addresses limitations in single-cell RNA sequencing by redistributing sequencing reads toward less abundant transcripts [9]:

Library Preparation: Generate full-length cDNA using standard single-cell RNA-seq protocols (10X Genomics 3' v3.1).

Target Identification: Identify highly abundant, low-variance transcripts for removal (255 protein-coding genes identified in human tissues).

CRISPR-Cas9 Treatment:

- Design sgRNA arrays against genomic-defined intervals, rRNAs, and exonic regions of target genes.

- Incubate dsDNA library with Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes.

Clean-up and Sequencing: Remove cleaved fragments and prepare sequencing library.

Data Analysis: Process data using standard single-cell analysis pipelines (Seurat, Scanpy).

This method redistributes approximately 50% of reads toward less abundant transcripts, enhancing detection of biologically distinct molecules [9].

Protocol 3: Prime Editor-Based Screening for Synonymous Mutations

Recent research has demonstrated that synonymous mutations can have functional impacts contrary to traditional understanding [10]:

Library Design: Design prime-editing guide RNA (pegRNA) library targeting synonymous mutation sites (297,900 engineered pegRNAs).

Delivery and Editing: Transfect cells with PEmax system components and pegRNA library.

Selection and Screening: Culture cells for multiple generations, monitoring fitness changes.

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA at multiple time points.

- Amplify target regions and sequence to determine pegRNA abundance.

- Use specialized machine learning tools to identify functional mutations.

Validation: Confirm hits using orthogonal assays (splicing assays, translation efficiency measurements).

This approach has identified functional synonymous mutations affecting mRNA splicing, transcription, and RNA folding [10].

Visualization of Key Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: CRISPR Functional Genomics Workflow

CRISPR Screening Steps

Diagram 2: Enhancer Interaction Analysis

Enhancer Interaction Modeling

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential research reagents and their applications in functional genomics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Genomics

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specifications | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Targeted genome editing, transcriptional modulation, epigenome editing | Cas9 nucleases, base editors, prime editors, CRISPRi/a [7] | Gene knockout, knock-in, gene regulation studies |

| Liquid Handling Systems | Automated sample preparation, assay assembly | Beckman Coulter Cydem VT, Tecan Veya, SPT Labtech firefly+ [8] | High-throughput screening, compound management |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Kits | Single-cell transcriptome profiling | 10X Genomics Chromium, MAS-Seq | Cellular heterogeneity, developmental biology |

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | Functional analysis in physiological contexts | INDIGO Melanocortin Receptor Reporter Assays [8] | Drug discovery, receptor biology, signaling studies |

| Model Organism Resources | Specialized strains and breeding | Zebrafish mutants, mouse knockouts, killifish strains | Disease modeling, phenotypic screening |

Selecting appropriate model organisms and experimental systems requires balancing biological relevance, practical considerations, and research objectives. Traditional models like mice and zebrafish continue to provide valuable insights, while emerging models such as killifish, ground squirrels, and bats offer unique advantages for specific research areas. The integration of advanced technologies like CRISPR screening, single-cell genomics, and high-throughput automation has dramatically expanded our ability to conduct functional genomics studies at scale. By carefully matching research questions with appropriate models and methodologies, scientists can optimize their experimental designs for more predictive and translatable results in both basic research and drug development.

This guide provides an objective comparison of commercial variant calling software that leverages public genomic resources, enabling researchers without extensive bioinformatics expertise to conduct robust functional genomics analyses. We focus on performance metrics derived from benchmarking studies that utilize gold-standard reference materials, presenting critical data on accuracy, sensitivity, and computational efficiency to inform software selection for research and clinical applications.

Public genomic databases provide foundational resources that empower researchers to conduct sophisticated genomic analyses without requiring massive in-house sequencing capacity. Three resources are particularly fundamental to comparative functional genomics: the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) serves as the primary repository for raw sequencing data from diverse studies and technologies [11]. The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Project systematically maps functional elements—including protein-coding genes, non-coding RNAs, and regulatory elements—across the human genome [12]. Finally, the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium provides high-confidence reference genomes and benchmark variants that serve as gold standards for validating genomic methodologies [13] [14].

These resources create an ecosystem where researchers can benchmark analytical tools against validated standards, access diverse genomic datasets without additional sequencing costs, and develop methods with properly controlled reference data. For commercial software developers, these public resources enable rigorous validation and continuous improvement of analytical pipelines. For researchers, they provide the reference standards needed to objectively evaluate tool performance for specific applications.

Benchmarking Experimental Design for Variant Calling Software

Experimental Protocol for Performance Validation

Objective benchmarking of variant calling software requires a standardized experimental framework that eliminates variables unrelated to software performance. The following protocol, adapted from contemporary benchmarking studies, ensures reproducible and scientifically valid comparisons [13] [14]:

1. Reference Dataset Selection: Utilize whole-exome sequencing data from the GIAB consortium for three established reference samples (HG001, HG002, HG003). These samples represent diverse ancestral backgrounds and are sequenced using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon Kit V5 with paired-end sequencing (minimum 125 bp read length). The GIAB provides established "truth sets" of high-confidence variants for these samples.

2. Data Preprocessing and Alignment: Download sequencing reads from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive using the following accession numbers: ERR1905890 (HG001), SRR2962669 (HG002), and SRR2962692 (HG003). Align all sequences to the human reference genome GRCh38 using the aligner specified by each software's default pipeline.

3. Variant Calling Execution: Process the aligned sequences through each variant calling software using default settings and germline variant calling modes. The tested software includes Illumina BaseSpace Sequence Hub (DRAGEN Enrichment), CLC Genomics Workbench (Lightspeed to Germline variants), Partek Flow (using both GATK and Freebayes+Samtools unionized calls), and Varsome Clinical (single sample germline analysis).

4. Performance Assessment: Compare output VCF files against GIAB high-confidence truth sets (v4.2.1) using the Variant Calling Assessment Tool (VCAT). VCAT employs hap.py for preprocessing and variant comparison, calculating true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) for both single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (indels) within exome capture regions.

5. Metric Calculation: Compute precision (TP/[TP+FP]), recall (TP/[TP+FN]), and F1 scores (harmonic mean of precision and recall) for each software. Additional metrics include runtime measurement and comparative analysis of variant overlap between tools.

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the standardized benchmarking workflow used to evaluate variant calling performance across software platforms.

Performance Comparison of Variant Calling Software

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize the performance characteristics of four commercial variant calling platforms when analyzed using the standardized benchmarking protocol described above. All data derived from benchmarking against GIAB gold standard datasets HG001, HG002, and HG003 [13] [14].

Table 1: Variant Calling Accuracy Metrics

| Software Platform | Variant Type | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) | True Positives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina DRAGEN | SNV | 99.5 | 99.3 | 99.4 | Highest |

| Indel | 97.1 | 95.8 | 96.4 | Highest | |

| CLC Genomics | SNV | 98.9 | 98.5 | 98.7 | High |

| Indel | 94.3 | 92.7 | 93.5 | High | |

| Partek Flow (GATK) | SNV | 98.2 | 97.8 | 98.0 | Moderate |

| Indel | 91.5 | 89.2 | 90.3 | Moderate | |

| Partek Flow (F+S) | SNV | 97.5 | 96.9 | 97.2 | Moderate |

| Indel | 88.7 | 86.4 | 87.5 | Lowest | |

| Varsome Clinical | SNV | 98.7 | 98.2 | 98.4 | High |

| Indel | 93.8 | 91.9 | 92.8 | High |

Table 2: Computational Efficiency and Practical Considerations

| Software Platform | Runtime Range (minutes) | Computing Environment | Cost Model (Annual SGD) | Programming Skills Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina DRAGEN | 29-36 | Cloud (SaaS) | $735 + credits | No |

| CLC Genomics | 6-25 | Local or Cloud | $8,450-$22,249 | No |

| Partek Flow | 216-1,782 | Cloud | $7,828 | No |

| Varsome Clinical | Not specified | Cloud | ~$2,490 (project-based) | No |

Performance Analysis and Interpretation

The benchmarking data reveals several critical patterns for software selection. Illumina DRAGEN Enrichment demonstrated superior performance across all accuracy metrics, achieving >99% precision and recall for SNVs and >96% for indels, while also maintaining competitive processing times (29-36 minutes) [13]. This combination of high accuracy and rapid analysis makes it particularly suitable for clinical applications where both precision and turnaround time are critical.

CLC Genomics Workbench offered the fastest processing times (6-25 minutes) with strong accuracy metrics, positioning it as an optimal solution for high-throughput research environments where computational efficiency is prioritized [13]. Varsome Clinical provided balanced performance with competitive accuracy and a flexible cost structure based on variant counts, which may be advantageous for projects with variable sample volumes.

All four software platforms shared 98-99% similarity in true positive variant calls, indicating substantial consensus on high-confidence variants [13]. The primary differentiators emerged in indel detection performance, false positive rates, and computational efficiency—factors that should guide selection based on specific research needs and resource constraints.

Table 3: Key Public Data Resources for Functional Genomics

| Resource | Primary Function | Application in Benchmarking | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) | Provides gold-standard reference genomes with validated variant calls | Truth sets for calculating precision/recall metrics | https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/genome-bottle |

| NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) | Repository for raw sequencing data from diverse studies | Source of test datasets (HG001/002/003) for benchmarking | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra |

| ENCODE Portal | Comprehensive collection of functional genomic elements | Provides regulatory context for variant interpretation | https://www.encodeproject.org |

| Variant Calling Assessment Tool (VCAT) | Standardized framework for variant calling evaluation | Performance assessment against GIAB benchmarks | Available within Illumina BaseSpace |

Table 4: Commercial Variant Calling Software Solutions

| Software | Variant Calling Engine | Key Strengths | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina DRAGEN | DRAGEN with machine learning | Highest SNV/indel accuracy; fast processing | Cloud-based with subscription model |

| CLC Genomics | Lightspeed algorithm | Fastest runtime; local or cloud deployment | Highest license cost for local installation |

| Partek Flow | GATK, Freebayes, Samtools | Flexible pipeline configuration | Slowest processing time |

| Varsome Clinical | Sentieon aligner & DNAscope | Pay-per-use pricing; integrated interpretation | Cost varies by project scale |

Accessing and Utilizing ENCODE Data

The ENCODE portal provides multiple access pathways for functional genomic data. Researchers can search metadata using text queries in the portal's interface or utilize the faceted browser to filter by assay type, biosample, or target. For programmatic access, the ENCODE REST API enables bulk download of data and metadata, facilitating integration into automated analysis pipelines [15].

Visualization tools represent another key feature, with a "Visualize Data" button available on assay pages that launches a Genome Browser track hub for genomic context exploration [15]. ENCODE data is also distributed through partner resources including the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) for processed data and the Sequence Read Archive for raw sequencing files, providing multiple access points depending on researcher preferences and analytical needs [15] [16].

Leveraging SRA for Comparative Genomics

The Sequence Read Archive contains vast amounts of sequencing data that can be repurposed for comparative analyses and validation studies. Effective utilization requires addressing several challenges: metadata heterogeneity, varying data quality across studies, and inconsistent experimental protocols [11]. Successful strategies include implementing rigorous quality control measures, applying batch effect correction when combining datasets, and utilizing standardized annotation pipelines to enhance comparability.

Advanced approaches for SRA data mining incorporate natural language processing to extract meaningful information from unstructured metadata fields, network analysis to identify relationships between sample collections, and integration with clinical databases to enhance translational relevance [11]. These methodologies enable researchers to construct larger, more powerful datasets by combining related studies while accounting for technical variability.

Based on comprehensive benchmarking against gold standard references, we provide the following recommendations for software selection in different research contexts:

For clinical applications requiring the highest accuracy: Illumina DRAGEN provides superior variant detection performance for both SNVs and indels, with processing times suitable for diagnostic timelines.

For high-throughput research environments: CLC Genomics offers the best balance of reasonable accuracy with exceptional processing speed, significantly reducing computational bottlenecks in large-scale studies.

For cost-sensitive projects with variable workloads: Varsome Clinical's flexible pricing model and competitive performance make it suitable for research groups with fluctuating analysis needs.

For method development and comparative studies: Partek Flow's flexible pipeline configuration allows researchers to evaluate different calling algorithms, though with longer processing times.

The integration of public resources like GIAB, SRA, and ENCODE provides the foundational infrastructure for objective software evaluation and enhances the reproducibility of genomic analyses. By leveraging these validated benchmarks and performance metrics, researchers can make informed decisions that align software capabilities with specific research objectives and operational constraints.

Formulating Clear Research Hypotheses and Comparative Questions

In comparative functional genomics, the precision of experimental outcomes is fundamentally determined by the initial clarity of the research hypothesis and comparative questions. This foundational step transcends mere academic formality, serving as the critical framework that guides experimental design, technology selection, and data interpretation. The primary objective of this guide is to provide researchers with a structured approach to formulating testable hypotheses and meaningful comparative questions, particularly within the context of functional genomics study design. We will objectively compare prevailing methodological approaches—ranging from established guilt-by-association techniques to emerging artificial intelligence (AI)-driven semantic design—by examining their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and applications through empirical data and standardized protocols.

Table 1: Core Components of a Research Hypothesis in Functional Genomics

| Component | Description | Example from Genomic Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | The biological entities or states being measured or compared. | Gene expression levels, variant impact, protein druggability. |

| Predicted Relationship | The expected causal or correlative link between variables. | A non-coding variant (variable) will alter the expression (relationship) of a specific oncogene. |

| Experimental System | The biological model and technological platform used for testing. | Primary B-cell lymphoma samples analyzed via single-cell DNA-RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) [17]. |

| Measurable Outcome | The quantitative or qualitative data used to support or refute the hypothesis. | Significant change in gene expression measured in transcripts per million (TPM) linked to a specific genotype [17]. |

Foundational Concepts: From "Guilt-by-Association" to Semantic Design

Traditional comparative genomics has long relied on the "guilt-by-association" principle, which posits that genes functioning together in pathways or complexes are often co-localized in genomes, such as in prokaryotic operons [3]. This principle leverages the genomic context of a gene—specifically, its proximity to other genes of known function—to infer its own role. While this approach has successfully identified numerous gene functions, its power is inherently limited by existing biological knowledge and observable evolutionary conservation.

A transformative shift is underway with the advent of semantic design, a generative AI approach that uses genomic language models like Evo. This method learns the "distributional semantics" of gene function across prokaryotic genomes, effectively understanding a gene by the company it keeps [3]. Rather than simply inferring the function of an existing gene, semantic design uses a DNA "prompt" encoding a desired genomic context to generate completely novel nucleotide sequences that are statistically enriched for targeted biological functions. This allows researchers to explore novel regions of functional sequence space, moving beyond the constraints of natural evolution to design synthetic genes and systems with desired properties [3].

Experimental Platforms & Comparative Frameworks

The choice of experimental platform is a critical determinant of the types of comparative questions a study can address. Below, we compare two foundational technologies for gene expression analysis and a novel integrated method for functional phenotyping.

Gene Expression Profiling: Microarrays vs. RNA-Seq

Gene expression profiling is a cornerstone of functional genomics, and the choice between microarray and RNA-Seq technologies represents a classic trade-off between cost, throughput, and informational depth.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Gene Expression Profiling Technologies

| Parameter | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Principle | Hybridization of fluorescently labeled cDNA to nucleic acid probes on a glass slide [18]. | High-throughput sequencing of cDNA fragments in parallel [18]. |

| Throughput & Cost | Reliable and more cost-effective (~$300/sample) [18]. | Higher cost per sample (up to $1000/sample) [18]. |

| Resolution & Dynamic Range | Capable of detecting a 2-fold change with reliability [18]. | Higher resolution; can accurately measure a 1.25-fold change; unlimited dynamic range [18]. |

| Genomic Discovery | Limited to transcripts represented on the array design [18]. | Can detect novel transcripts, splice variants, and non-coding RNA without prior knowledge [18]. |

| Key Application Strength | Cost-effective gene expression profiling in model organisms with well-annotated genomes [18]. | Discovery-driven research, non-model organisms, and comprehensive transcriptome characterization [18]. |

Functional Phenotyping of Genomic Variants

A significant challenge in genomics is linking genetic variants, especially non-coding ones, to their functional outcomes. Single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) is a novel platform that addresses this by enabling simultaneous profiling of genomic DNA loci and transcriptome in thousands of single cells [17].

Diagram 1: SDR-seq Workflow for Functional Phenotyping.

Experimental Protocol: SDR-seq for Variant Phenotyping [17]

- Cell Preparation: Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension and fix with paraformaldehyde (PFA) or glyoxal. Glyoxal is often preferred for superior RNA target detection and reduced nucleic acid cross-linking.

- In Situ Reverse Transcription: Perform reverse transcription inside fixed cells using custom primers to add a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI), sample barcode, and capture sequence to cDNA molecules.

- Droplet Partitioning & Lysis: Load cells onto a microfluidics platform (e.g., Mission Bio Tapestri) to encapsulate single cells into droplets. Subsequently, lyse cells within droplets to release gDNA and cDNA.

- Multiplexed Targeted PCR: Inside each droplet, perform a multiplexed PCR using panels of forward and reverse primers specific for hundreds of targeted gDNA loci (e.g., coding/non-coding variants) and RNA transcripts.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Break emulsions, pool amplicons, and prepare separate next-generation sequencing libraries for gDNA and RNA using distinct overhangs on the primers. This allows for optimized sequencing of both modalities.

- Data Integration: Confidently link precise genotypes from gDNA sequencing to gene expression changes from RNA sequencing within the same single cell.

Hypothesis Formulation in Practice: Key Research Paradigms

AI-Driven Generative Genomics

The Evo model exemplifies how AI can be directed by a clear hypothesis to explore new sequence space. The core hypothesis is that a generative genomic language model, when prompted with a functional genomic context, can design novel, functional genes that diverge significantly from natural sequences [3].

Supporting Experimental Data:

- Researchers prompted Evo with the context of toxin-antitoxin systems to generate novel toxic proteins. One generated toxin, EvoRelE1, exhibited strong growth inhibition (≈70% reduction in relative survival) in E. coli, despite having only 71% sequence identity to the nearest known RelE toxin [3].

- When subsequently prompted with the EvoRelE1 sequence, the model generated conjugate antitoxin genes, which were then experimentally validated to neutralize the toxin's activity [3]. This demonstrates a success rate for generating functional multi-component systems.

Machine Learning for Target Discovery

In drug discovery, a common comparative question is: "Can sequence-derived features accurately predict a protein's potential as a drug target?" This was tested in a study that compared multiple machine learning algorithms using 443 protein features [19] [20].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Druggable Protein Prediction

| Algorithm | Reported Accuracy | Key Strengths | Feature Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Network (NN) | 89.98% [19] | Superior accuracy in classifying druggable proteins based on sequence features. | 443 sequence-derived features [19]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | N/A | Used for feature selection, identifying the optimal set of 130 most-relevant features [19]. | Optimized set of 130 features. |

| Other Algorithms | Varied | Comparative analysis included multiple common classifiers to identify the best performer [20]. | Various feature sets. |

Comparative Genomics of Host Adaptation

Hypotheses regarding the genetic basis of niche specialization can be tested through large-scale comparative genomics. For instance, a study of 4,366 bacterial genomes hypothesized that human-associated pathogens would exhibit distinct genomic signatures of adaptation compared to those from animal or environmental sources [21].

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Genomic Analysis [21]

- Genome Dataset Curation: Collect high-quality, non-redundant bacterial genomes from public databases, annotated with ecological niche (e.g., human, animal, environment).

- Functional Annotation: Predict open reading frames and annotate genes using databases like COG (functional categories), dbCAN (carbohydrate-active enzymes), VFDB (virulence factors), and CARD (antibiotic resistance genes).

- Phylogenetic Construction: Build a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using universal single-copy genes to account for evolutionary relationships.

- Statistical & Machine Learning Analysis: Use genome-wide association studies (GWAS) tools like Scoary and machine learning algorithms to identify genes and features significantly enriched in specific niches, controlling for phylogenetic relatedness.

Key Finding: The study confirmed the hypothesis, revealing that human-associated bacteria from the phylum Pseudomonadota exhibited a strategy of gene acquisition (e.g., higher counts of virulence factors), while Actinomycetota and Bacillota often employed genome reduction for adaptation [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Functional Genomics

| Tool / Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Evo Genomic Language Model | Generative AI model trained on prokaryotic DNA to design novel functional sequences based on genomic context prompts [3]. | Semantic design of de novo genes and multi-gene systems (e.g., toxin-antitoxin systems, anti-CRISPRs). |

| SynGenome Database | A publicly available database containing over 120 billion base pairs of AI-generated genomic sequences [3]. | Provides a resource for semantic design across thousands of functional terms. |

| SDR-seq Platform | A droplet-based method for simultaneous targeted gDNA and RNA sequencing in thousands of single cells [17]. | Functional phenotyping of coding and non-coding genomic variants in their endogenous context. |

| Mission Bio Tapestri | A microfluidics instrument and platform for performing single-cell targeted DNA and multi-ome analyses [17]. | The underlying technology enabling the high-throughput multiplexed PCR in SDR-seq. |

| Polyamine Oxidase (PAO) Genes | A gene family studied as a model for functional analysis of stress response in plants [22]. | Comparative genomics and expression analysis to identify candidates for drought-resilient crop breeding (e.g., SbPAO5/6 in sorghum). |

Formulating a powerful research hypothesis in comparative functional genomics requires integrating deep biological inquiry with a clear understanding of technological capabilities and limitations. The most robust studies are those that leverage a comparative framework—whether contrasting traditional and AI-driven methods, different algorithmic approaches, or evolutionary adaptations across niches—to generate unambiguous, data-driven conclusions.

Diagram 2: Hypothesis-Driven Research Workflow.

By adopting the structured approaches and utilizing the toolkit outlined in this guide, researchers can design studies that not only answer fundamental biological questions but also push the boundaries of discovery through the strategic application of comparative functional genomics.

The principle of Guilt by Association (GBA) represents a cornerstone methodology in functional genomics, operating on the premise that genes with shared functions tend to co-occur across biological contexts [23]. This foundational concept underpins diverse gene discovery approaches, from phylogenetic profiling in eukaryotes to operon-based predictions in prokaryotes [24] [25]. The core hypothesis suggests that functionally related genes maintain associations through evolutionary conservation, genomic co-localization, or coordinated expression, enabling researchers to infer unknown gene functions from their associated partners with characterized roles [23].

As genomic technologies have advanced, GBA strategies have evolved from focused, small-scale analyses to genome-wide computational approaches [23]. These methods now form an essential component of the functional genomics toolkit, enabling systematic gene function prediction across diverse species. However, different GBA implementations yield substantially different results, with varying degrees of validation and applicability to drug development pipelines [26] [27]. This comparative analysis examines the methodological spectrum of GBA approaches, their performance characteristics, and their utility in pharmaceutical research and development.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Principles

Conceptual Framework of Gene Association

The GBA paradigm operates through multiple biological mechanisms that create detectable associations between functionally related genes. Phylogenetic profiling detects functional linkages by correlating the presence and absence patterns of homologs across diverse species, where genes functioning together in a pathway or complex tend to be jointly gained or lost during evolution [24]. This approach successfully identified human cilia genes and mitochondrial calcium influx genes by tracking their co-occurrence across eukaryotic species [24].

In prokaryotic systems, genomic context methods leverage operon structures where functionally related genes cluster together on chromosomes [3] [25]. The development of genomic language models like Evo demonstrates that these contextual relationships can be learned from sequence data alone, enabling semantic design of novel genes with specified functions based on their genomic neighborhood [3]. This approach effectively operationalizes the distributional hypothesis that "you shall know a gene by the company it keeps" [3].

Methodological Variations in GBA Implementation

- Network-based GBA: Constructs gene association networks from protein interactions, genetic interactions, or co-expression data, then propagates functional annotations across network edges [23] [26]. Performance depends heavily on network quality and the algorithms used for annotation transfer.

- Phylogenetic profiling: Employs evolutionary co-occurrence patterns to identify functional modules [24]. The human OrthoGroup Phylogenetic (hOP) profiling method overcame historical challenges with gene duplication events by automatically profiling over 30,000 groups of homologous human genes across 177 eukaryotic species [24].

- Operon-based GBA: Utilizes conserved gene adjacency in bacterial and archaeal genomes to infer functional relationships [25]. Metagenomic applications face unique challenges in resolving functional associations from sequence fragments [25].

- Machine learning integration: Combines multiple association types through algorithms that weight different evidence sources to improve prediction accuracy [26].

Comparative Performance of GBA Methodologies

Quantitative Assessment Across Biological Contexts

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of GBA Approaches

| Method Category | Typical Data Sources | Strengths | Limitations | Validation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network-Based GBA | Protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions, co-expression | Captures diverse relationship types; applicable to any organism | Highly biased toward well-studied genes; limited novel discoveries | Limited utility for identifying autism risk genes [26] |

| Phylogenetic Profiling | Genomic sequences across multiple species | Evolutionarily informative; identifies co-evolved modules | Requires many sequenced genomes; sensitive to homology detection | Successfully identified WASH complex and cilia/basal body genes [24] |

| Operon-Based GBA | Bacterial genomic sequences | High precision in prokaryotes; homology-free predictions | Limited to prokaryotes; requires operon prediction | 85% positive predictive value for metagenomic operons [25] |

| Genomic Language Models | Whole genome sequences | Generates novel functional sequences; no prior functional knowledge required | Black-box nature; limited explainability | Functional anti-CRISPRs and toxin-antitoxin systems validated [3] |

Comparison with Genetic Association Studies

Table 2: GBA vs. Genetic Association for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Gene Discovery

| Study Type | Number of Studies | Performance with Known ASD Genes (SFARI-HC) | Performance with Novel ASD Genes | Bias Toward Multifunctional Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBA Machine Learning | 13 published studies | Moderate performance in cross-validation | Poor performance with novel genes not used in training | Significant bias toward generic gene annotations [26] |

| Genetic Association (TADA) | 5 major studies | High performance with known genes | Successfully identified novel high-confidence ASD genes | Minimal bias; based on statistical evidence from sequencing [26] |

When evaluated against established benchmarks, GBA methods demonstrated limited utility for identifying novel autism spectrum disorder risk genes compared to genetic association studies [26]. The machine learning approaches performed comparably to generic measures of gene constraint (e.g., pLI scores) rather than providing ASD-specific predictions [26]. This suggests that apparent GBA performance in cross-validation may reflect biases toward well-studied, multifunctional genes rather than genuine biological insights.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Phylogenetic Profiling Workflow

The human OrthoGroup Phylogenetic (hOP) profiling method exemplifies a robust GBA implementation for eukaryotic gene discovery [24]. The protocol involves:

Orthogroup Construction: Iteratively cluster human genes into 31,406 orthogroups using a modified bidirectional best hit strategy with BLASTp bit scores, addressing challenges from gene duplication events [24].

Profile Generation: Create binary phylogenetic profiles for each orthogroup across 177 eukaryotic species, with presence/absence calls determined by sequence homology thresholds [24].

Co-occurrence Scoring: Calculate pairwise similarity between profiles using a specialized metric that accounts for phylogenetic tree topology and shared evolutionary losses [24].

Module Identification: Cluster correlated profiles into functional modules (hOP-modules) ranging from 2 to over 50 genes, predicting functions for uncharacterized members based on associated genes [24].

This approach successfully predicted functions for hundreds of poorly characterized human genes and identified evolutionary constraints distinguishing protein complexes from signaling networks [24].

Genomic Language Model Protocol

The Evo model demonstrates a novel approach to GBA through in-context generation of functional sequences [3]:

Model Training: Pretrain transformer architecture on diverse prokaryotic genomic sequences from OpenGenome database at single-nucleotide resolution [3].

Context Prompting: Supply genomic context (e.g., genes of known function) as input prompts to guide generation of novel sequences with related functions [3].

Sequence Generation: Autocomplete partial genes or operons using Evo 1.5 model with 131K context length, trained on 450 billion tokens [3].

Functional Filtering: Apply in silico filters for protein-protein interaction potential and novelty requirements before experimental testing [3].

This semantic design approach generated functional anti-CRISPR proteins and toxin-antitoxin systems, including de novo genes without significant sequence similarity to natural proteins [3].

Metagenomic Operon Analysis

For metagenomic functional annotation, operon-based GBA employs distinct methodology [25]:

Data Acquisition: Obtain metagenomic sequences from public repositories (e.g., IMG/M database), implementing stringent quality control including N50 ≥50,000 bp and CheckM completeness ≥95% [25].

Operon Prediction: Identify potential operons using co-directional intergenic distances with confidence threshold equivalent to positive predictive value of 0.85 based on E. coli K12 operons from RegulonDB [25].

Annotation Transfer: Apply guilt by association within predicted operons, transferring functional annotations between co-operonic genes based on Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) categories excluding [R] and [S] categories [25].

This homology-free approach enables functional annotation for metagenomic sequences without reference genomes, though performance depends on operon prediction accuracy [25].

Critical Limitations and Methodological Constraints

Systemic Biases in GBA Applications

The theoretical foundation of GBA faces significant challenges in practical implementation. Multifunctionality bias represents a critical limitation, where highly connected "hub" genes in biological networks tend to accumulate numerous functional annotations regardless of specific biological relevance [23]. This bias enables GBA methods to perform well in cross-validation by simply associating new functions with already well-characterized genes, without providing genuine novel biological insights [23] [26].

Research demonstrates that functional information within gene networks typically concentrates in a tiny fraction of interactions whose properties cannot be generalized across the network [23]. In one striking example, a million-edge network could be reduced to just 23 critical associations while retaining most GBA performance, indicating that cross-validation metrics dramatically overestimate generalizable function prediction capability [23].

Evolutionary Constraints on Detection Sensitivity

The evolutionary processes shaping genomes create fundamental detection limits for different GBA approaches. Genes affecting multiple traits ("multitrait genes") often undergo strong purifying selection that removes severe functional variants from populations [27]. Consequently, burden tests focusing on protein-altering variants struggle to detect these genes, while genome-wide association studies (GWAS) can identify them through regulatory variants with more limited effects [27].

This evolutionary filtering creates a systematic blind spot where genes with broad biological importance become invisible to certain discovery methods, skewing functional predictions toward specialized genes with limited pleiotropy [27]. The complementary strengths of different approaches highlight the need for method selection based on specific biological questions rather than one-size-fits-all applications.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for GBA Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | IMG/M [25], OpenGenome [3], gcPathogen [21] | Source of genomic and metagenomic sequences | All GBA approaches requiring multi-species genomic data |

| Orthology Resources | OrthoGroup profiles [24], COG database [25] | Evolutionary classification of genes | Phylogenetic profiling, functional annotation |

| Analysis Tools | Scoary [21], CheckM [21], Prokka [21] | Genome comparison, quality control, annotation | Comparative genomics, operon prediction |

| Experimental Validation | Growth inhibition assays [3], Interaction assays | Functional confirmation of predictions | All discovery pipelines requiring biological validation |

| Specialized Algorithms | Evo genomic language model [3], hOP-profile analysis [24] | Novel sequence generation, co-evolution detection | Specific methodological applications |

Guilt by association remains a valuable heuristic for gene discovery, but its utility depends critically on methodological implementation and biological context. Phylogenetic profiling provides evolutionarily validated functional predictions for eukaryotic systems [24], while operon-based methods offer high precision for prokaryotic gene annotation [25]. Emerging approaches like genomic language models demonstrate potential for generating novel functional sequences beyond natural evolutionary boundaries [3].

For drug development applications, GBA methods should complement rather than replace genetic association studies [26] [27]. The limited real-world success of GBA in identifying bona fide disease genes underscores the importance of statistical genetic evidence for target validation [26]. Future methodological development should focus on correcting multifunctionality biases [23] and integrating evolutionary constraints [27] to improve prediction specificity and translational applicability.

From Data to Insight: Methodologies, Workflows, and Practical Applications

Functional genomics aims to understand how genes and intergenic regions contribute to biological processes by studying the genome's dynamic components on a system-wide scale [28]. This field investigates the flow of genetic information across multiple molecular levels, from DNA to RNA to protein, to build comprehensive models linking genotype to phenotype [28]. Among the most powerful tools enabling this research are high-throughput sequencing technologies, particularly RNA-seq for analyzing transcriptomes, ChIP-seq for mapping protein-DNA interactions, and ATAC-seq for profiling chromatin accessibility. These technologies have revolutionized our ability to decipher the regulatory code underlying cellular function, disease mechanisms, and developmental processes.

Each technique interrogates a distinct layer of genomic regulation: RNA-seq captures gene expression outputs, ChIP-seq identifies transcription factor binding sites and histone modifications, and ATAC-seq reveals the accessible chromatin landscape where regulatory activity occurs. When integrated, these data types provide a multi-dimensional view of the genomic regulatory network, offering unprecedented insights into how genetic information is controlled and executed in biological systems [29]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these foundational technologies, their performance characteristics, experimental considerations, and applications in functional genomics research.

Technology Comparison at a Glance

Table 1: Comparative overview of RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, and ATAC-seq technologies

| Feature | RNA-seq | ChIP-seq | ATAC-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Gene expression quantification, transcript discovery, splicing analysis | Transcription factor binding, histone modification profiling | Genome-wide chromatin accessibility, open chromatin regions |

| Molecular Target | RNA transcripts | Protein-bound DNA fragments | Accessible DNA regions |

| Typical Input | Total RNA or mRNA | Crosslinked or native chromatin (10⁵-10⁷ cells for conventional) [30] | 500-50,000 cells [31] |

| Key Steps | RNA extraction, library prep, sequencing | Crosslinking, fragmentation, immunoprecipitation, library prep | Transposase fragmentation and tagging, PCR amplification |

| Sequencing Depth | 20-50 million reads (standard) | 20-60 million reads (TF ChIP-seq) | 50 million reads (open chromatin) [31] |

| Key Advantages | Comprehensive transcriptome view, no prior knowledge needed | High specificity for protein-DNA interactions, precise binding site mapping | Simple protocol, low input requirement, fast processing time |

| Main Limitations | RNA instability, bias in library prep | Antibody quality critical, high input requirements, complex protocol | Mitochondrial DNA contamination, background noise |

Table 2: Typical data output characteristics and analysis requirements

| Parameter | RNA-seq | ChIP-seq | ATAC-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analysis | Read alignment, transcript assembly, quantification | Read alignment, peak calling, motif analysis | Read alignment, peak calling, nucleosome positioning |

| Differential Analysis Tools | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [32] | DESeq2, MACS2 | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [32] |

| Specialized Analyses | Alternative splicing, fusion genes, novel transcripts | Footprinting, histone modification enrichment | Nucleosome positioning, footprinting, chromatin state |

| ENCODE Pipeline | Available [33] | Available [33] | Available [33] |

RNA-seq: Transcriptome Profiling Technology

Principles and Applications

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides a comprehensive snapshot of the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample at a specific moment. This technology has largely supplanted microarrays due to its higher sensitivity, broader dynamic range, and ability to discover novel transcripts and splicing variants without requiring prior knowledge of the genome [28]. In functional genomics, RNA-seq enables researchers to quantify expression levels across different conditions, identify differentially expressed genes, characterize splice variants, and detect fusion transcripts in cancer. The technique is particularly valuable for connecting genetic variation to phenotypic outcomes through expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis and for understanding temporal changes during development or disease progression.

Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Library Construction:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction or commercial kits, assessing quality via RNA Integrity Number (RIN > 8 recommended).

- RNA Selection: Perform poly-A selection for mRNA enrichment or ribosomal RNA depletion for total RNA analysis.

- Fragmentation: Fragment RNA to 200-300 nucleotides using divalent cations under elevated temperature.

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe fragmented RNA using random hexamer priming to generate first-strand cDNA, followed by second-strand synthesis.

- Library Preparation: Ligate sequencing adapters, optionally incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for PCR duplicates, and perform size selection.

- Sequencing: Conduct paired-end sequencing on Illumina platforms (typically 75-150 bp read length) to a depth of 20-50 million reads per sample.

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Quality Control: Assess raw read quality using FastQC, trim adapters with Trimmomatic or cutadapt.

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using splice-aware aligners (STAR, HISAT2).

- Quantification: Generate count matrices using featureCounts or HTSeq.

- Differential Expression: Identify significantly changed genes using DESeq2 or edgeR.

- Advanced Analysis: Perform pathway enrichment, alternative splicing, and variant calling.

Figure 1: RNA-seq experimental and computational workflow

ChIP-seq: Protein-DNA Interaction Mapping

Principles and Applications

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) identifies genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors and histone modifications, providing critical insights into the epigenetic regulatory landscape [30]. The technique relies on antibodies to capture specific DNA-binding proteins or histone modifications along with their associated DNA fragments. ChIP-seq has been instrumental in mapping enhancers, promoters, insulators, and other regulatory elements, and in understanding how chromatin states influence gene expression programs in development and disease. Advanced variations like CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag have further improved the resolution and reduced input requirements, enabling applications in limited cell populations [30].

Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Immunoprecipitation:

- Crosslinking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10-15 minutes at room temperature to fix protein-DNA interactions (X-ChIP). For histone modifications, native ChIP (N-ChIP) without crosslinking can be used [30].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells and isolate nuclei using appropriate buffers.

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Sonicate chromatin to 200-600 bp fragments (for crosslinked samples) or use micrococcal nuclease digestion (for native samples).

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate fragmented chromatin with validated, specific antibodies overnight at 4°C. Use protein A/G beads to capture antibody-bound complexes.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads extensively with low- and high-salt buffers to remove non-specific binding. Elute complexes with elution buffer.

- Reverse Crosslinking: Incubate at 65°C overnight with high salt to reverse crosslinks.

- DNA Purification: Treat with RNase A and proteinase K, then purify DNA using phenol-chloroform extraction or columns.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries using standard methods and sequence on Illumina platforms.

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Quality Control: Assess read quality and adapter contamination.

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using Bowtie2 or BWA.

- Peak Calling: Identify significant enrichment regions using MACS2, SICER, or HOMER.

- Motif Analysis: Discover enriched transcription factor binding motifs.

- Differential Binding: Compare conditions using tools like DESeq2 or diffBind.

Figure 2: ChIP-seq experimental and computational workflow

ATAC-seq: Chromatin Accessibility Profiling

Principles and Applications

The Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) identifies genomically accessible regions where the chromatin structure is "open" and potentially available for transcription factor binding [31]. This technique utilizes a hyperactive Tn5 transposase that simultaneously cuts open chromatin regions and inserts sequencing adapters, providing a rapid, sensitive method for mapping regulatory elements with low input requirements (500-50,000 cells) [31]. ATAC-seq has largely replaced DNase-seq and FAIRE-seq due to its simpler protocol, higher signal-to-noise ratio, and ability to simultaneously map nucleosome positions. The technique is particularly valuable for identifying cell-type-specific enhancers and promoters, mapping regulatory changes during differentiation, and understanding disease-associated genetic variants in non-coding regions.

Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Tagmentation:

- Nuclei Preparation: Isolate nuclei from cells using lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630).

- Tagmentation Reaction: Incubate nuclei with Tn5 transposase (37°C for 30 minutes) to fragment accessible DNA and add adapters simultaneously.

- DNA Purification: Clean up tagmented DNA using silica membrane columns or SPRI beads.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify library with 10-12 cycles using barcoded primers.

- Size Selection: Purify libraries (typically 100-700 bp) using SPRI beads.

- Sequencing: Perform high-depth sequencing on Illumina platforms (50-200 million reads for nucleosome positioning).

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Quality Control: Assess fragment size distribution for nucleosome patterning.

- Alignment: Map reads using BWA-MEM or Bowtie2 after removing mitochondrial reads.

- Peak Calling: Identify open chromatin regions using MACS2 or specialized tools.

- Nucleosome Positioning: Analyze fragment size distribution to map nucleosome positions.

- Footprinting: Detect transcription factor binding within accessible regions.

- Differential Accessibility: Identify changes using DESeq2, edgeR, or limma [32].

Figure 3: ATAC-seq experimental and computational workflow

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Technical Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance benchmarks across sequencing technologies

| Performance Metric | RNA-seq | ChIP-seq | ATAC-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Requirements | 10 ng - 1 μg total RNA | 10⁵-10⁷ cells (conventional) [30], 100-1000 cells (CUT&RUN) [30] | 500-50,000 cells [31] |

| Protocol Duration | 2-3 days | 3-4 days (conventional), 1 day (CUT&Tag) | 1 day |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | 20-50 million reads | 20-60 million reads | 50-200 million reads |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (dual indexes) | Moderate to high | High (dual indexes) |

| Batch Effect Sensitivity | Moderate | High | High (needs correction) [32] |

| Reproducibility | High (ICC: 0.8-0.95) | Moderate to high (antibody-dependent) | High (ICC: 0.85-0.95) |

Analytical Performance and Statistical Considerations

Statistical methods for differential analysis represent a critical aspect of technology performance. For both RNA-seq and ATAC-seq, tools based on negative binomial distributions (DESeq2, edgeR) are widely used, though their performance varies significantly with signal strength and sample size [32]. Benchmarking studies using simulated ATAC-seq data have shown that limma achieves highest sensitivity for low-signal regions (1 CPM), while DESeq2 maintains the lowest false positive rates (<1%) across different signal levels [32]. Sample size dramatically affects statistical power, with methods requiring different numbers of replicates to achieve optimal sensitivity - for ATAC-seq, at least 3-4 replicates are recommended for robust differential analysis, though ENCODE standards typically require only 2 replicates [32].

Batch effects present significant challenges in all high-throughput sequencing technologies, particularly for ATAC-seq where batch-effect correction can dramatically improve sensitivity in differential analysis [32]. Specialized tools like BeCorrect have been developed specifically for batch effect correction and visualization of ATAC-seq data [32]. For ChIP-seq, antibody quality and specificity remain the primary factors influencing data quality, with recommendations to use validated antibodies and include appropriate controls.

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis

Data Integration Strategies

The true power of functional genomics emerges when multiple data types are integrated to build comprehensive regulatory models. A typical integrative analysis might combine ATAC-seq or ChIP-seq data with RNA-seq to link regulatory elements to target genes and ultimately to phenotypic outcomes [29]. The general workflow for such integration includes:

- Independent Processing: Each data type is processed through its specialized pipeline (peak calling for ATAC-seq/ChIP-seq, quantification for RNA-seq).

- Element Classification: Regulatory elements are grouped by their activity patterns (e.g., activated, repressed) across conditions.

- Gene Grouping: Genes are clustered by expression patterns and annotated for functional enrichment.

- Regulatory Linking: Putative regulatory elements are connected to target genes based on genomic proximity and correlation between accessibility/occupancy and expression.

- Network Inference: Transcription factors are linked to their targets through motif analysis, binding data, and expression correlation.

This approach enables the identification of active cis- and trans-regulatory pathways that drive biological processes, such as differentiation or disease progression [29]. Validation of these networks typically involves chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) to confirm physical interactions, CRISPR-based genome editing to test functional importance, and additional ChIP-seq experiments to verify transcription factor binding [29].

The Research Toolkit

Table 4: Essential research reagents and computational tools for sequencing technologies

| Category | RNA-seq | ChIP-seq | ATAC-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Reagents | Poly-T oligos, RNase inhibitors, reverse transcriptase | High-quality antibodies, protein A/G beads, formaldehyde | Tn5 transposase, cell permeabilization reagents, nucleases |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina TruSeq, NEBNext Ultra II | Illumina TruSeq ChIP Library Prep | Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1, Nextera DNA Flex |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, RSeQC, MultiQC [31] | FastQC, ChIPQC, MultiQC [31] | FastQC, ATACseqQC [31], MultiQC |

| Primary Analysis Tools | STAR, HISAT2, featureCounts | Bowtie2, BWA, MACS2 | BWA-MEM, Bowtie2, MACS2 |

| Differential Analysis | DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom | DESeq2, diffBind | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [32] |

| Specialized Tools | StringTie (assembly), DEXSeq (splicing) | HOMER (motifs), CentriMo (motif discovery) | HINT-ATAC (footprinting), NucleoATAC (nucleosome) |

RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, and ATAC-seq each provide unique and complementary views of the functional genome, enabling researchers to dissect the complex regulatory networks underlying biological systems. While RNA-seq captures the transcriptional output and ChIP-seq maps specific protein-DNA interactions, ATAC-seq offers a comprehensive view of the accessible chromatin landscape with simplified experimental requirements. The choice between these technologies depends on the specific research question, with considerations for input material, resolution needs, and analytical resources.