CRISPR vs RNAi: A Comprehensive Comparison of Efficiency, Applications, and Best Practices for Genetic Research

This article provides a detailed comparison of CRISPR and RNA interference (RNAi) technologies for genetic perturbation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR vs RNAi: A Comprehensive Comparison of Efficiency, Applications, and Best Practices for Genetic Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of CRISPR and RNA interference (RNAi) technologies for genetic perturbation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational mechanisms of gene knockout (CRISPR) versus knockdown (RNAi), explores their methodological workflows and application-specific uses, offers troubleshooting guidance for optimizing efficiency and minimizing off-target effects, and presents a critical validation of their performance based on large-scale screening data. The synthesis aims to serve as a definitive guide for selecting the appropriate gene silencing tool based on experimental objectives.

Knockout vs. Knockdown: Understanding the Fundamental Mechanisms of CRISPR and RNAi

In the field of functional genomics, determining gene function most directly involves disrupting normal gene expression and studying the resulting phenotypes [1]. For over a decade, RNA interference (RNAi) has been the predominant method for gene silencing, offering researchers a way to reduce gene expression through mRNA degradation [2] [1]. However, the more recent advent of CRISPR-based technologies has provided an alternative approach that operates at the DNA level, enabling permanent gene disruption [2] [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their mechanisms, efficiency, specificity, and optimal applications in modern research and drug development contexts.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

The primary distinction between RNAi and CRISPR lies in their level of action and the permanence of their effects. RNAi functions at the mRNA level to achieve gene knockdown, while CRISPR acts at the DNA level to create permanent knockout.

RNA Interference (RNAi): The Knockdown Pioneer

RNAi utilizes an evolutionarily conserved endogenous pathway that regulates gene expression via small RNAs [1]. The process involves:

- Introduction of Trigger Molecules: Synthetic small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) are introduced into cells [2] [1].

- RISC Loading and Target Recognition: The introduced RNA is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which identifies complementary mRNA sequences [2] [1].

- mRNA Degradation: The argonaute protein within RISC cleaves the target mRNA, preventing translation and effectively reducing protein production [2].

This technology leverages natural cellular machinery present in practically every mammalian somatic cell, requiring no prior genetic manipulation of the target cell line [1]. The effects are typically transient and reversible, as the technique targets mRNA without altering the underlying DNA sequence [2].

CRISPR-Cas9: The Knockout Revolution

The CRISPR-Cas9 system operates through a fundamentally different mechanism:

- Two-Component System: CRISPR editing requires a guide RNA (gRNA) for target specificity and a CRISPR-associated endonuclease protein (Cas9) that cuts DNA [2].

- DNA Targeting and Cleavage: The gRNA directs Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences, where the nuclease creates double-strand breaks [2].

- Cellular Repair and Gene Disruption: The cell repairs these breaks via error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the reading frame and create null alleles [2].

This process results in permanent gene knockout at the DNA level, completely eliminating protein production rather than merely reducing it [2].

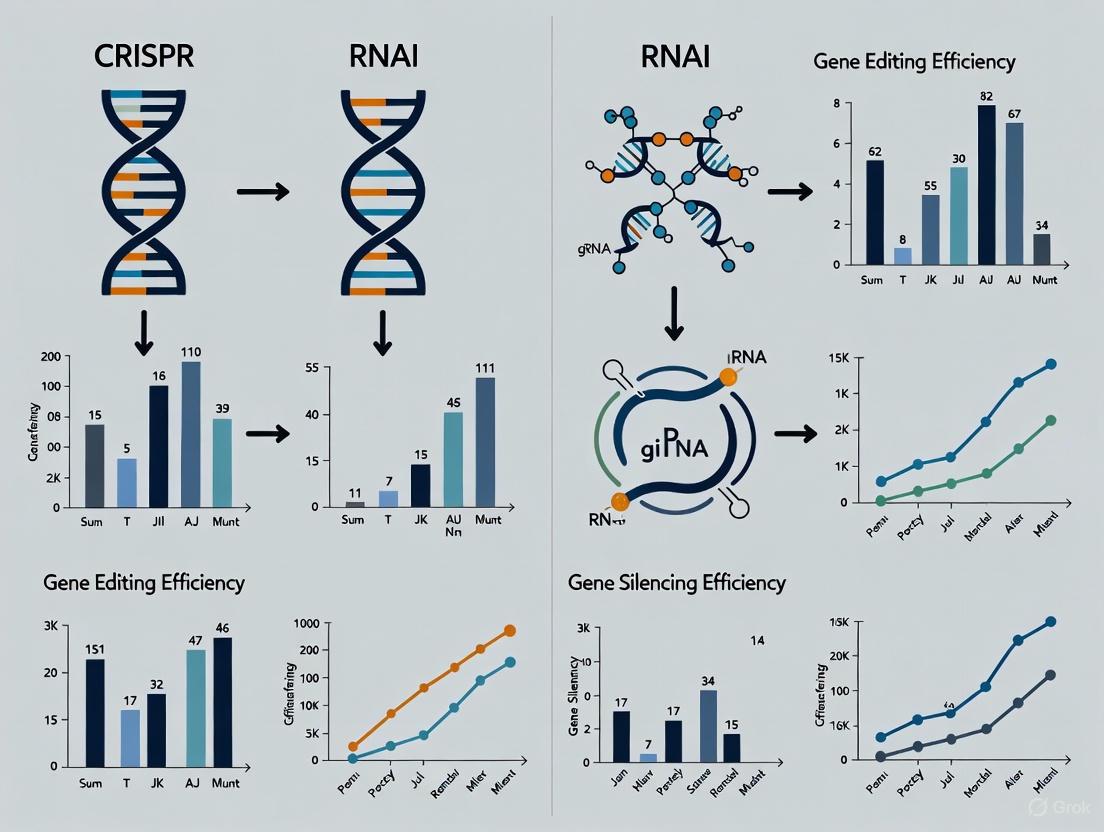

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanisms of each technology:

Comparative Efficiency and Specificity

Large-scale comparative studies have revealed significant differences in the efficiency and specificity profiles of RNAi versus CRISPR technologies.

On-Target Efficacy

Both technologies demonstrate strong on-target effects when properly designed:

- RNAi Efficacy: Well-designed shRNAs can achieve substantial reduction in target mRNA and protein levels, though complete silencing is rare [2] [3].

- CRISPR Efficacy: CRISPR generates complete gene knockout when successful indels occur, completely eliminating protein function [2].

- Direct Comparison: A large-scale study analyzing 13,000 shRNAs and 373 sgRNAs found that the on-target efficacies of both technologies are comparable in terms of producing measurable phenotypic effects [3] [4].

Off-Target Effects

This represents the most significant practical difference between the technologies:

- RNAi Off-Target Issues: RNAi suffers from pervasive sequence-specific off-target effects where the silencing trigger can enter the microRNA pathway, potentially repressing hundreds of transcripts with limited sequence complementarity [2] [3]. Analysis of gene expression profiles from over 13,000 shRNAs revealed that "microRNA-like off-target effects of RNAi are far stronger and more pervasive than generally appreciated" [3] [4].

- CRISPR Specificity: While early CRISPR systems showed some off-target cleavage activity, advances in guide RNA design, modified Cas9 variants, and improved delivery methods have substantially reduced these effects [2]. Comparative analysis shows "CRISPR technology is far less susceptible to systematic off-target effects" than RNAi [3] [4].

- Mitigation Strategies: For RNAi, computational approaches like consensus gene signatures (CGS) can help identify true on-target effects [3] [4]. For CRISPR, bioinformatics tools and chemically modified guide RNAs minimize off-target risks [2] [5].

Table: Comparative Analysis of RNAi vs. CRISPR Technologies

| Parameter | RNAi (Knockdown) | CRISPR (Knockout) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | mRNA degradation/translational inhibition [2] | DNA cleavage with permanent disruption [2] |

| Level of Effect | Transcriptional/translational level [2] | Genetic level [2] |

| Permanence | Transient, reversible [2] | Permanent, heritable [2] |

| On-Target Efficacy | Strong knockdown, rarely complete [2] [3] | Complete knockout when successful [2] |

| Off-Target Effects | High, pervasive miRNA-like effects [3] [4] | Lower, more controllable [2] [3] |

| Key Advantages | Reversible, studies essential genes, rapid implementation [2] | Complete elimination, better specificity, versatile platforms [2] [3] |

| Major Limitations | Off-target effects, incomplete silencing [2] [3] | Lethal for essential genes, ethical concerns for therapeutics [2] |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

The practical implementation of RNAi and CRISPR technologies involves distinct experimental workflows, each with specific requirements and considerations.

RNAi Experimental Workflow

RNAi experiments typically follow this sequence:

- Design Phase: Design highly specific siRNAs or shRNAs that target only intended genes [2].

- Delivery: Introduce silencing triggers into cells using plasmid vectors, synthetic siRNAs, PCR products, or in vitro transcribed siRNAs [2].

- Validation: Measure silencing efficiency through qRT-PCR (mRNA levels), immunoblotting/immunofluorescence (protein levels), or phenotypic monitoring [2].

The endogenous presence of RNAi machinery (Dicer and RISC) in mammalian cells simplifies delivery and implementation [2].

CRISPR Experimental Workflow

CRISPR genome editing involves these critical steps:

- Guide RNA Design: Design efficient and specific guide RNAs using state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools [2].

- Component Delivery: Transfer CRISPR components into cells via plasmids, in vitro transcribed RNAs, or preassembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [2].

- Editing Validation: Analyze editing efficiency using methods such as ICE analysis, sequencing, or functional assays [2].

The RNP delivery format has emerged as the preferred choice for many researchers due to higher editing efficiencies and more reproducible results [2].

The experimental workflow for both technologies is summarized below:

Advanced Applications and Technical Variations

Both RNAi and CRISPR platforms have evolved beyond their core functions, developing into sophisticated toolkits for precise genetic manipulation.

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi)

A significant advancement in gene silencing technology is CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), which bridges the capabilities of both RNAi and traditional CRISPR:

- Mechanism: Uses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains like KRAB to block transcription without DNA cleavage [6].

- Advantages: Offers reversible silencing like RNAi but with DNA-level specificity like CRISPR [6].

- Efficiency: Studies in iPSCs show CRISPRi gene repression is "more efficient and homogenous across cell populations" compared to CRISPR nuclease approaches [6].

- Applications: Particularly valuable for studying essential genes where complete knockout would be lethal, or for modeling dosage-sensitive processes [2] [6].

High-Throughput Genetic Screening

Both technologies enable genome-scale functional screening, albeit with different strengths:

- RNAi Screening: Established approach with comprehensive libraries, but confounded by off-target effects that can produce inconsistent results between screens [2] [3] [7].

- CRISPR Screening: Emerging as the preferred tool for phenotypic screens due to higher specificity, with studies showing more reliable identification of essential genes [2] [3].

- Complementary Use: Some researchers now use both technologies in orthogonal validation approaches, where hits from RNAi screens are confirmed with CRISPR and vice versa [7].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Silencing Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNAi Triggers | Synthetic siRNA, shRNA vectors, PCR products | Induce transient gene knockdown; compatible with endogenous cellular machinery [2] |

| CRISPR Delivery Formats | Plasmid vectors, in vitro transcribed RNAs, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes | Enable permanent gene knockout; RNP format offers highest editing efficiency [2] |

| Validation Tools | qRT-PCR, Western blot, immunofluorescence, ICE analysis | Measure silencing efficiency at mRNA, protein, or DNA level [2] |

| Specialized Systems | dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi), base editors, prime editors | Enable precise gene regulation without double-strand breaks [6] [5] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Guide RNA design algorithms, off-target prediction software | Optimize specificity and efficiency of genetic perturbations [5] |

Selection Guidelines for Specific Research Applications

Choosing between RNAi and CRISPR depends on multiple factors, including research goals, gene characteristics, and experimental constraints.

When to Prefer RNAi (Knockdown)

RNAi remains the preferred choice in these scenarios:

- Essential Gene Studies: When studying genes whose complete knockout would be lethal, as RNAi enables partial reduction of function [2].

- Reversible Phenotypes: When investigating processes where temporal control and reversibility are important for mechanistic studies [2].

- Rapid Screening: For projects requiring quick implementation without extensive cell line engineering [1].

- Transcriptional Studies: When targeting nuclear transcripts or non-coding RNAs where the act of transcription itself may have functional consequences [1].

When to Prefer CRISPR (Knockout)

CRISPR offers significant advantages for these applications:

- Complete Loss-of-Function: When complete elimination of protein function is required to observe phenotypes [2].

- High-Throughput Screens: For genetic screens where specificity and minimal false positives are critical [2] [3].

- Therapeutic Development: For creating disease models with permanent genetic changes or developing gene therapies [8].

- Precision Editing: When using advanced variants like base editing or prime editing for specific nucleotide changes [5].

Emerging Best Practices

The research community is increasingly adopting these practices:

- Orthogonal Validation: Using both technologies in tandem to confirm critical findings [7].

- CRISPRi for Intermediate Approaches: Employing CRISPRi when reversible but highly specific silencing is needed [6].

- Advanced Bioinformatics: Leveraging machine learning and deep learning tools to optimize guide RNA and siRNA design [5].

The choice between permanent gene knockout using CRISPR and reversible gene knockdown using RNAi represents a fundamental strategic decision in experimental design. RNAi technology offers the advantage of reversible, tunable silencing that is valuable for studying essential genes and transient biological processes. However, it suffers from significant off-target effects that can complicate data interpretation. CRISPR technology provides more specific, permanent gene disruption but can be lethal for essential genes and raises additional ethical considerations for therapeutic applications. Rather than viewing these technologies as competitors, researchers should consider them complementary tools in the genetic toolbox [7]. The optimal choice depends on specific research questions, gene characteristics, and experimental requirements, with emerging approaches like CRISPRi bridging the gap between these platforms. As both technologies continue to evolve, particularly with advances in machine learning-guided design [5], researchers are equipped with an increasingly sophisticated arsenal for deciphering gene function and developing novel therapeutics.

In the field of functional genomics and therapeutic development, two powerful technologies enable researchers to suppress gene expression: the DNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas9 system and the mRNA-targeting RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) machinery. These systems operate at fundamentally different levels of the central dogma—CRISPR-Cas9 permanently modifies genomic DNA to create knockouts, while RISC transiently intercepts and destroys messenger RNA to create knockdowns [2]. Understanding their distinct mechanisms, experimental workflows, and performance characteristics is essential for selecting the appropriate gene silencing method for specific research or therapeutic objectives. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these technologies, framed within the broader context of CRISPR versus RNAi efficiency research, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Biological Origins

The RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) Machinery

Biological Origin and Discovery: The RNA interference (RNAi) pathway was first observed in plants in 1990, but its mechanism remained unclear until Andrew Fire and Craig Mello's seminal 1998 work in Caenorhabditis elegans, for which they received the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They demonstrated that double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)—but not single-stranded RNA—mediates sequence-specific gene silencing [2] [9]. This pathway mimics endogenous microRNA (miRNA) mechanisms that naturally regulate gene expression in eukaryotic cells.

Core Mechanism: The RISC machinery operates at the post-transcriptional level, targeting messenger RNA (mRNA) for degradation or translational inhibition. The process involves several key steps:

- Input Processing: Exogenous double-stranded RNAs (such as siRNAs or shRNAs) or endogenous pre-miRNAs are loaded into the cellular machinery. The endonuclease Dicer cleaves these dsRNAs into small fragments approximately 21 nucleotides in length [2] [9].

- RISC Loading: These small RNAs associate with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a multi-protein complex. The antisense (guide) strand is retained, while the sense strand is degraded.

- Target Recognition and Cleavage: The guide RNA directs RISC to complementary mRNA sequences. With perfect complementarity (typical of siRNAs), the Argonaute protein within RISC cleaves the mRNA, leading to its degradation. With imperfect pairing (typical of miRNAs), translation is stalled without mRNA cleavage, as the RISC complex physically blocks ribosomal progression [2] [9].

The primary function of this natural RNA interference is to regulate gene expression and, in some cases, confer resistance to pathogens [2]. The outcome is a reduction (knockdown) of protein expression, but rarely a complete abolition.

Diagram: The mRNA-Targeting RISC Machinery Pathway. The process begins with double-stranded RNA input, proceeds through Dicer processing and RISC loading, and culminates in mRNA cleavage or translational inhibition.

The DNA-Targeting CRISPR-Cas9 Complex

Biological Origin and Discovery: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins function as an adaptive immune system in bacteria. First identified in 1987, their significance in microbial immunity was established in 2007 [2] [10]. The system protects bacteria from viral infection by storing fragments of viral DNA and using them to create guide RNAs that direct Cas nucleases to cleave matching viral sequences upon re-infection. This natural system was repurposed for programmable genome editing in eukaryotic cells by 2013 [2].

Core Mechanism: CRISPR-Cas9 operates at the DNA level, creating permanent genetic modifications. The system requires two components: a guide RNA (gRNA) and a Cas9 nuclease [10].

- Complex Assembly: The gRNA, composed of a scaffold sequence for Cas9-binding and a ~20-nucleotide spacer that defines the genomic target, forms a ribonucleoprotein complex with the Cas9 enzyme [10].

- Target Localization: This complex scans the genome for a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence (e.g., NGG for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9). Upon locating a PAM, the gRNA's seed sequence anneals to the target DNA. Sufficient homology between the gRNA and the target DNA induces a conformational change in Cas9 [10].

- DNA Cleavage: The Cas9 nuclease domains RuvC and HNH create a double-strand break (DSB) in the target DNA, typically ~3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [2] [10].

- DNA Repair and Outcome: The cell repairs the DSB primarily via the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). These indels can disrupt the open reading frame, leading to a complete knockout of the gene [2] [10]. Alternatively, in the presence of a donor DNA template, the break can be repaired via homology-directed repair (HDR) to introduce specific edits or insertions.

Diagram: The DNA-Targeting CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism. The guide RNA and Cas9 nuclease form a complex that binds DNA adjacent to a PAM sequence, introduces a double-strand break, and triggers cellular repair that often results in gene knockout.

Comparative Performance and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters

The following table summarizes critical performance metrics for CRISPR-Cas9 and RISC-based RNAi, drawing from comparative studies and experimental data.

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 System | RISC/RNAi System |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | Genomic DNA [2] | Messenger RNA (mRNA) [2] |

| Genetic Outcome | Permanent knockout (via frameshift indels) [2] [10] | Transient knockdown (via mRNA degradation) [2] |

| Typical Efficiency | High editing efficiency; near-complete protein loss [2] | Variable; rarely achieves >90% protein knockdown [2] |

| Specificity & Off-Target Effects | Lower sequence-specific off-target effects; can be minimized with high-fidelity Cas9 variants and optimized sgRNAs [2] | High off-target potential due to seed-sequence-mediated and interferon-pathway activation [2] [9] |

| Duration of Effect | Stable, permanent modification [2] | Transient; requires re-delivery or stable vector integration [9] |

| Key Applications | Complete loss-of-function studies, gene knockout generation, therapeutic correction of mutations [2] [11] | Studies of essential genes, transient suppression, functional validation in same cells via reversibility [2] |

Key Experimental Evidence and Validation Data

Off-Target Effects Profile: A significant comparative limitation of RNAi is its propensity for off-target effects. These can be sequence-dependent (targeting mRNAs with partial complementarity, particularly in the "seed" region) or sequence-independent (e.g., triggering an interferon response) [2] [9]. Studies have shown that control, non-targeting shRNAs can cause unexpected phenotypic changes, such as synaptic retraction in neurons or learning deficits in rodents, confounding data interpretation [9]. While CRISPR also had initial issues with off-target cleavage, advances in guide RNA design tools and engineered high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) have substantially reduced this problem. Recent comparative studies confirm that CRISPR has far fewer off-target effects than RNAi [2].

Efficacy in Genetic Screens: Both technologies are used in high-throughput loss-of-function screens. Initially, RNAi libraries were the standard tool. However, CRISPR knockout (CRISPRn) libraries have now largely supplanted them for such applications because they produce more complete and consistent phenotypes due to permanent gene disruption. The higher specificity and potency of CRISPR lead to a lower false-positive and false-negative rate in identifying essential genes and drug targets [2] [12]. The drive for efficiency has led to the development of minimal, focused genome-wide libraries that are 50% smaller while preserving sensitivity and specificity, enabling broader deployment at scale [12].

Detailed Experimental Workflows

RNAi Workflow Using shRNA/siRNA

Step 1: Design of Silencing RNAs

- siRNA: Design synthetic 21-23 nt duplex RNAs with perfect complementarity to the target mRNA. Specificity is a primary concern, and algorithms help select sequences that minimize off-targeting [2] [9].

- shRNA: Design DNA vectors encoding short hairpin RNAs, typically under the control of a U6 RNA polymerase III promoter. The shRNA transcript folds into a stem-loop structure that is processed by Dicer into a functional siRNA [9].

Step 2: Delivery into Cells

- siRNA: Transient transfection of synthetic RNA duplexes using lipid-based or other transfection reagents. Effects are transient, typically lasting 3-7 days [2].

- shRNA: Delivery via plasmid vectors or viral vectors (lentivirus, AAV) for stable genomic integration and long-term, continuous expression [2] [9].

Step 3: Validation of Knockdown Efficiency

- mRNA Quantification: Measure transcript levels using quantitative RT-PCR 24-72 hours post-transfection [2].

- Protein Analysis: Assess protein reduction 48-96 hours post-transfection using immunoblotting (Western blot) or immunofluorescence [2].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Monitor for expected phenotypic changes resulting from target gene suppression [2].

Diagram: RNAi Experimental Workflow. The process involves designing silencing RNAs, delivering them into cells, and validating knockdown efficacy at the molecular and phenotypic levels.

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Gene Knockout

Step 1: Guide RNA (gRNA) Design

- Use state-of-the-art design tools to select a ~20 nt spacer sequence with high on-target activity and minimal off-target potential. The target site must be adjacent to a PAM sequence (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) [2] [10]. Advanced models like CRISPR_HNN, a hybrid deep neural network, are now being developed to further improve the prediction accuracy of sgRNA on-target activity [13].

Step 2: Delivery of CRISPR Components

- Plasmid Vectors: Transfect cells with plasmids encoding both the gRNA and the Cas9 nuclease.

- In Vitro Transcribed (IVT) RNAs: Deliver IVT gRNA and Cas9 mRNA.

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes: The preferred method for high efficiency and reproducibility involves delivering pre-assembled complexes of purified Cas9 protein and synthetic gRNA. This method reduces off-target effects and avoids the need for in vivo transcription [2] [10].

Step 3: Validation of Editing and Knockout

- DNA Analysis: Assess editing efficiency at the target locus using methods such as ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) analysis, T7E1 assay, or Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products [2] [10].

- Functional Validation: Confirm loss of protein expression via immunoblotting and/or assess the resulting phenotypic consequence of gene knockout [2] [10].

Diagram: CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Experimental Workflow. The key steps involve computational gRNA design, delivery of editing components in various formats, and multi-layered validation of the resulting genetic and phenotypic changes.

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease Variants | Engineered versions of the Cas9 protein with improved properties. | SpCas9: Wild-type; HF-Cas9: High-fidelity (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9); Cas9-NG: PAM-flexible (NG PAM) [10]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Synthetic RNA or DNA template directing Cas9 to target locus. | Chemically modified sgRNA: Increases stability and reduces off-target effects; crRNA:tracrRNA duplex: Two-part system for some Cas orthologs [2] [10]. |

| Delivery Vectors & Particles | Vehicles for introducing components into cells. | Plasmids: For gRNA and Cas9; Viral Vectors (Lentivirus, AAV): For stable delivery; Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): For efficient RNP or RNA delivery, especially in vivo [2] [11]. |

| Design & Analysis Software | Computational tools for experiment planning and data validation. | gRNA Design Tools: (e.g., from Synthego, Broad Institute); Off-target prediction algorithms; ICE Analysis: Tool for quantifying editing efficiency from Sanger data [2] [13] [10]. |

| Benchmarking Resources | Reference data and software for quality control. | R Package for Screen QC: For assessing quality of genome-wide CRISPR screens (e.g., HT-29 benchmark data) [14]. |

The choice between DNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas9 and mRNA-targeting RISC machinery is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather depends on the specific research question. CRISPR-Cas9 is generally the preferred tool for complete, permanent gene knockout with higher specificity, making it ideal for definitive loss-of-function studies, genetic screening, and therapeutic gene disruption [2] [11]. In contrast, RISC/RNAi is suitable for studying the effects of partial, transient gene knockdown, which can be essential for investigating the function of essential genes or achieving reversible phenotypes [2] [9].

The field continues to evolve rapidly. For CRISPR, efforts are focused on improving delivery (e.g., with LNPs), enhancing specificity with novel Cas variants, and expanding into new modalities like base editing and prime editing [10] [11]. In the RNAi space, chemical modifications to siRNAs are being used to improve stability and reduce off-target effects [9]. Furthermore, the lines between these technologies are blurring, with the development of CRISPR systems that target RNA (e.g., Cas13) and CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) using dCas9 to block transcription without cutting DNA, offering a reversible alternative akin to RNAi [2] [10]. This ongoing innovation provides researchers with an ever-expanding and precise toolkit for interrogating gene function and developing novel therapeutics.

The debate between CRISPR and RNAi technologies is a pivotal one in modern genetic research. At the heart of this discussion are their fundamental components: the guide RNA and Cas nuclease for CRISPR, and the siRNA/shRNA and Dicer enzyme for RNAi. These core elements dictate the mechanisms, efficiencies, and specificities of gene silencing and editing. This guide provides an objective comparison of these systems, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate gene perturbation tools.

Core Components and Mechanisms of Action

The fundamental difference between these technologies lies in their target and mechanism: CRISPR-Cas systems act at the DNA level to create permanent genetic changes, while RNAi operates at the mRNA level to achieve temporary gene silencing [2] [15] [16].

CRISPR-Cas System: DNA-Level Intervention

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, repurposed for precise genome editing. Its operation requires two core components:

- Guide RNA (gRNA): A synthetic RNA molecule composed of a ~20 nucleotide sequence designed to be complementary to a specific target DNA locus. It acts as a homing device, guiding the Cas nuclease to the intended genomic location [2] [16].

- Cas Nuclease (e.g., Cas9): An enzyme that functions as a "molecular scissor." Upon binding to the target DNA site specified by the gRNA, the Cas nuclease induces a double-strand break (DSB) [2].

The subsequent cellular repair of this DSB leads to the genetic outcome:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels). When these indels occur within a gene's coding sequence, they can disrupt the reading frame, leading to a complete gene knockout [2] [17].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that can be co-opted with a donor DNA template to introduce specific sequence changes or insertions, known as knock-in [15].

RNAi System: mRNA-Level Intervention

RNA interference is a natural cellular process for post-transcriptional gene regulation. Its experimental application relies on the following core components:

- siRNA (small interfering RNA) or shRNA (short hairpin RNA): These are the effector molecules that initiate silencing.

- siRNA: Synthetic, double-stranded RNA molecules (~21-23 nucleotides) that are directly introduced into the cell cytoplasm [18] [17].

- shRNA: A DNA vector is delivered to the cell, which is then transcribed into an RNA molecule that folds into a tight hairpin structure. This shRNA is exported to the cytoplasm [18].

- Dicer: A cytoplasmic endonuclease that is a key part of the cell's native RNAi machinery. It processes long double-stranded RNA or shRNA into mature siRNA fragments [2] [17].

The mechanism proceeds as follows:

- Processing: shRNA is cleaved by Dicer into siRNA [18].

- RISC Loading: The siRNA duplex is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The complex is activated, and the passenger strand of the siRNA is discarded [2] [17].

- Targeting and Cleavage: The guide strand within RISC binds to a complementary mRNA sequence. The "Slicer" enzyme (a component of RISC, such as Argonaute 2) then cleaves the target mRNA, leading to its degradation and preventing translation. This results in a transient gene knockdown, reducing but not eliminating gene expression [2] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the distinct operational pathways of these two systems.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in the efficiency, specificity, and functional outcomes of CRISPR and RNAi technologies.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics derived from published comparative studies.

| Feature | CRISPR/Cas9 System | RNAi (shRNA/siRNA) System |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Outcome | Permanent knockout (at DNA level) [15] [16] | Reversible knockdown (at mRNA level) [15] [16] |

| Silencing Efficiency | High (Complete gene disruption) [19] | Moderate to Low (Incomplete protein knockdown) [19] [16] |

| Off-Target Effects | Low (With optimized gRNA design) [2] [19] | High (Due to partial complementarity) [2] [18] [19] |

| Key Advantage | Complete elimination of gene function; high specificity [16] | Ability to study essential genes via dose-dependent silencing [16] |

| Primary Limitation | Lethal when targeting essential genes [16] | Incomplete knockdown can lead to ambiguous results [16] |

Supporting Experimental Data: A Head-to-Head Screen

A seminal study directly compared genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 and shRNA screens in the human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line K562 to identify genes essential for cell growth [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Library Design: A CRISPR library (4 sgRNAs per gene) and an shRNA library (25 shRNAs per gene) were used.

- Delivery: Both libraries were delivered into K562 cells via lentiviral infection.

- Screening: Cells were passaged for two weeks to allow depletion of cells bearing essential gene perturbations.

- Analysis: Deep sequencing was used to quantify the abundance of each gRNA or shRNA at the beginning (T0) and end (T14) of the experiment. Depleted guides indicated essential genes.

Key Findings:

- Precision: Both screens performed well in distinguishing known essential and non-essential genes (Area Under the Curve, AUC > 0.90) [20].

- Scope Discrepancy: The CRISPR screen identified ~4,500 candidate essential genes at a 10% false positive rate, while the shRNA screen identified only ~3,100. Only about 1,200 genes were identified by both technologies, indicating low correlation and suggesting each method reveals distinct biological information [20].

- Biological Pathways: The screens enriched for different essential biological processes. For example, CRISPR uniquely identified genes in the electron transport chain as essential, whereas the shRNA screen specifically identified all subunits of the chaperonin-containing T-complex [20].

- Synergistic Value: A statistical framework (casTLE) developed to combine data from both screens achieved superior performance (AUC of 0.98), demonstrating that the technologies are complementary [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

For researchers seeking to implement these comparisons, detailed methodologies are critical.

Protocol for a Parallel CRISPR and RNAi Screening Experiment

This protocol is adapted from the systematic comparison by et al. in Nature Biotechnology (2016) [20].

Objective: To identify genes essential for cell proliferation in a human cell line using parallel CRISPR knockout and shRNA knockdown.

Materials:

- Cell Line: K562 chronic myelogenous leukemia cells (or other cell line of interest).

- Libraries: Genome-wide lentiviral CRISPR knockout library (e.g., 4 sgRNAs/gene) and genome-wide lentiviral shRNA library (e.g., 25 shRNAs/gene).

- Reagents: Lentiviral packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G), polybrene, puromycin, cell culture media, and reagents for genomic DNA extraction and PCR.

Procedure:

- Virus Production: Produce lentivirus for both the CRISPR and shRNA libraries in HEK293T cells via transfection.

- Cell Infection & Selection:

- Infect K562 cells at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI < 0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one viral construct.

- At 24 hours post-infection, treat cells with puromycin for 3-5 days to select for successfully transduced cells.

- Screen Execution:

- Harvest a representative sample of the selected cell population as the "T0" reference time point.

- Split the remaining population into biological replicates and continue passaging for approximately 14 population doublings (T14), maintaining sufficient library representation.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Extract genomic DNA from T0 and T14 samples.

- Amplify the integrated shRNA or gRNA sequences by PCR using specific primers.

- Subject the PCR products to high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis:

- Map sequencing reads to the library manifest to count the abundance of each guide.

- Use algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK for CRISPR, RIGER for shRNA) to identify significantly depleted guides in T14 vs. T0, which correspond to essential genes.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents required for executing such genetic screens.

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral gRNA/shRNA Library | Delivers the genetic perturbation elements (gRNA or shRNA) stably into the host cell genome. | Genome-wide or pathway-focused loss-of-function screens [20]. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cell Line | Provides a constant source of the Cas9 nuclease for CRISPR knockout experiments. | Creating stable cell lines for repetitive CRISPR screening [19]. |

| Lentiviral Packaging Plasmids | psPAX2 (packaging) and pMD2.G (envelope) are used to produce replication-incompetent lentiviral particles. | Generating the virus for library delivery in HEK293T cells [20]. |

| Puromycin | A selection antibiotic; cells expressing a puromycin resistance gene from the lentiviral vector survive. | Enriching for successfully transduced cells post-infection [20]. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically synthesized, high-purity guide RNA for RNP complex formation. | Offers highest editing efficiency and reduced off-target effects in CRISPR experiments [2]. |

| dCas9-KRAB Fusion | Catalytically "dead" Cas9 fused to a transcriptional repressor domain (KRAB). | Used in CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for reversible gene knockdown without altering DNA [17]. |

The core components of CRISPR and RNAi dictate their distinct applications in genetic research. The guide RNA and Cas nuclease of CRISPR work in concert to create permanent, high-specificity knockouts at the DNA level, making it the superior tool for definitive loss-of-function studies and screening. In contrast, the siRNA/shRNA and Dicer enzyme of the RNAi pathway mediate a transient, mRNA-level knockdown, which remains valuable for studying essential genes and achieving titratable silencing. Experimental evidence confirms that while CRISPR generally offers higher efficiency and lower off-target effects, the two technologies are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary. A synergistic approach, leveraging the strengths of both systems, often provides the most robust and biologically insightful validation of gene function in drug discovery and basic research.

The exploration of cellular repair pathways is pivotal for advancing genetic engineering techniques, particularly when comparing the mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9 and RNA interference (RNAi). While both technologies enable gene silencing, they operate through fundamentally distinct cellular machinery: CRISPR-Cas9 induces permanent DNA breaks repaired via pathways like non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), whereas endogenous RNAi utilizes the cell's native machinery for post-transcriptional gene regulation without altering DNA sequence [2]. This distinction creates significant implications for experimental design, therapeutic applications, and functional genomics screening.

The core difference lies in their level of action and persistence. CRISPR-Cas9 generates knockouts through permanent genetic modifications at the DNA level, while RNAi produces knockdowns through temporary suppression at the mRNA level [2]. CRISPR-Cas9 achieves this by introducing double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which the cell primarily repairs via the error-prone NHEJ pathway, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function [2] [21]. In contrast, RNAi employs endogenous cellular machinery including Dicer and the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to degrade or translationally repress target mRNA molecules, providing reversible and titratable gene suppression [2] [22].

Molecular Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis

The CRISPR-Cas9 and NHEJ Pathway

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as a programmable DNA-editing tool derived from bacterial adaptive immunity [21]. This system requires two key components: a guide RNA (gRNA) that specifies the target DNA sequence through complementary base pairing, and the Cas9 nuclease that creates double-strand breaks at the targeted site [2]. The process begins with the formation of a ribonucleoprotein complex where the gRNA directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence [21]. Upon binding, Cas9 undergoes conformational changes that activate its nuclease domains, generating a blunt-ended DSB [2].

Cellular response to these breaks immediately engages DNA repair machinery, with NHEJ representing the dominant pathway in most mammalian cells [2] [21]. The NHEJ pathway operates through a series of coordinated steps: first, the Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer recognizes and binds to the broken DNA ends; then, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) recruits and activates additional repair factors; next, Artemis nuclease processes damaged ends; and finally, DNA ligase IV (LigIV), in complex with XRCC4 and XLF, catalyzes DNA end ligation [23] [21]. This repair process is inherently error-prone due to occasional nucleotide insertions or deletions during end processing, making it ideal for generating gene knockouts when precise editing is not required [2].

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 and NHEJ Pathway. The CRISPR-Cas9 system creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are repaired via the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining pathway, often resulting in gene-disrupting insertions or deletions (indels).

Endogenous RNA Interference Machinery

The endogenous RNAi pathway represents a natural cellular mechanism for sequence-specific gene regulation that operates at the post-transcriptional level [2] [22]. This conserved biological pathway utilizes small non-coding RNAs as guide molecules to identify complementary mRNA targets for degradation or translational repression. The two primary classes of small RNAs involved in RNAi are small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) derived from exogenous sources or long double-stranded RNA, and microRNAs (miRNAs) encoded by endogenous genes [2]. Both pathways converge on the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which executes the silencing function.

The RNAi mechanism begins with the introduction or cellular production of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules. These dsRNA substrates are recognized and processed by the RNase III enzyme Dicer, which cleaves them into small 21-23 nucleotide fragments with characteristic 2-nucleotide overhangs on their 3' ends [2]. These small RNA duplexes are then loaded into the RISC complex, where the passenger strand is removed and degraded while the guide strand is retained. The mature RISC complex uses this guide strand to identify complementary mRNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing [2]. Upon binding, the catalytic component Argonaute (Ago) within RISC cleaves the target mRNA if there is perfect or near-perfect complementarity (siRNA pathway), or alternatively, translational repression occurs with imperfect pairing (miRNA pathway) [2]. The silenced mRNA is subsequently degraded by cellular nucleases, preventing protein production without altering the underlying DNA sequence.

Figure 2: Endogenous RNAi Machinery. Double-stranded RNA is processed by Dicer and loaded into RISC, which guides sequence-specific mRNA cleavage or translational repression without altering genomic DNA.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

CRISPR-Cas9 Screening with NHEJ Utilization

CRISPR knockout screening represents a powerful approach for identifying essential genes and functional genetic elements through targeted disruption of coding sequences [2] [20]. The experimental workflow begins with the design and synthesis of guide RNA (gRNA) libraries targeting the genes of interest. State-of-the-art design tools help identify optimal gRNA sequences with maximal on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects [2]. A typical high-quality library includes 4-6 gRNAs per gene to ensure statistical robustness and account for potential variation in individual gRNA efficiency [20].

The delivery of CRISPR components into target cells represents a critical step in the experimental process. While early approaches utilized plasmid vectors encoding both Cas9 and gRNA sequences, recent advancements favor ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes consisting of preassembled Cas9 protein and synthetic gRNA [2]. RNP delivery offers significant advantages including reduced off-target effects, higher editing efficiency, and immediate nuclease activity without delays from transcription and translation. Following delivery, cells are cultured for several days to allow for protein turnover, enabling the phenotypic consequences of gene knockout to manifest.

The effectiveness of CRISPR screening depends heavily on the efficient generation and identification of knockout cells. Editing efficiency is typically analyzed using methods such as Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) analysis or T7 endonuclease I (T7EI) assays [2] [23]. For positive selection screens, edited cells are subjected to selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment), and gRNA abundance is tracked through next-generation sequencing to identify enrichments associated with resistance. In negative selection screens, essential genes are identified by quantifying the depletion of corresponding gRNAs from the population over time [20]. Recent studies demonstrate that CRISPR screens achieve high performance in detecting essential genes, with area under the curve (AUC) metrics exceeding 0.90 in validation experiments [20].

RNA Interference Screening Protocols

RNAi screening employs a distinct methodological approach centered on post-transcriptional gene silencing rather than genomic alteration [2] [20]. The process initiates with the design of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting specific mRNA sequences. Optimal design parameters include GC content between 30-50%, specificity for the target transcript, and minimal similarity to unrelated genes to reduce off-target effects. For large-scale screens, libraries typically incorporate multiple RNAi constructs per gene (often 5-10 hairpins) to account for variations in knockdown efficiency [20].

Delivery methods for RNAi components depend on the selected modality. Synthetic siRNAs are typically introduced via lipid-based transfection, providing transient knockdown lasting 3-7 days. For stable gene silencing, shRNA sequences are cloned into lentiviral or retroviral vectors that integrate into the host genome, enabling long-term suppression [2] [20]. Following delivery, a critical incubation period of 48-72 hours allows for cellular processing of RNAi triggers, degradation of existing target proteins, and manifestation of phenotypic effects.

Validation of knockdown efficiency represents an essential quality control step in RNAi screening. Quantitative RT-PCR measures reduction in target mRNA levels, while immunoblotting or immunofluorescence assesses decreases in protein expression [2]. In high-throughput formats, successful screens incorporate robust normalization procedures to account for variations in transfection efficiency and cell viability. Modern RNAi libraries have demonstrated improved performance in identifying essential genes compared to earlier iterations, with studies reporting AUC values >0.90 when using optimized designs [20].

Comparative Performance Data

Quantitative Comparison of Screening Technologies

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the performance characteristics of CRISPR and RNAi technologies for functional genomics. A systematic comparison conducted in the human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line K562 evaluated parallel screens using both a 4 sgRNA/gene CRISPR-Cas9 library and a 25 hairpin/gene shRNA library [20]. Both technologies demonstrated high performance in detecting essential genes, with area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve exceeding 0.90 for each method [20].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CRISPR-Cas9 and RNAi Genetic Screens

| Performance Metric | CRISPR-Cas9 | RNAi | Combined Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | >0.90 [20] | >0.90 [20] | 0.98 [20] |

| True Positive Rate (at 1% FPR) | >60% [20] | >60% [20] | >85% [20] |

| Genes Identified (at 10% FPR) | ~4,500 [20] | ~3,100 [20] | ~4,500 [20] |

| Overlap Between Technologies | ~1,200 genes identified by both methods [20] | ||

| Gene Knockdown/Knockout Efficiency | Complete protein disruption [2] | Partial to near-complete protein reduction [2] | Complementary coverage |

| Biological Processes Identified | Electron transport chain genes [20] | Chaperonin-containing T-complex [20] | Comprehensive coverage |

Despite similar precision metrics, the two technologies exhibited surprisingly low correlation in hit identification, suggesting they may reveal different aspects of biology [20]. The CRISPR screen identified approximately 4,500 genes with growth phenotypes compared to 3,100 genes in the shRNA screen, with only about 1,200 genes overlapping between the two approaches [20]. This partial overlap highlights the complementary nature of these technologies rather than direct redundancy.

Technology-Specific Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Characteristics of CRISPR-Cas9 and RNAi Technologies

| Characteristic | CRISPR-Cas9 | RNAi |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | DNA-level knockout via NHEJ [2] | mRNA-level knockdown [2] |

| Persistence of Effect | Permanent [2] | Transient (days to weeks) [2] |

| Specificity | High (with optimized gRNA design) [2] | Moderate (off-target effects common) [2] [20] |

| Efficiency | High knockout rates [2] | Variable knockdown efficiency [20] |

| Applications | Complete gene disruption, essential gene identification [2] [20] | Titratable knockdown, essential gene studies [2] [20] |

| Key Advantages | Complete gene disruption; High specificity; Permanent effect [2] | Titratable knockdown; Reversible; Studies of essential genes [2] |

| Major Limitations | Lethal for essential genes; Off-target effects (reduced with RNP) [2] | High off-target effects; Incomplete knockdown [2] [20] |

Biological context significantly influences technology performance. CRISPR screens preferentially identified genes involved in processes such as the electron transport chain, while RNAi screens more effectively detected essential components of complexes like the chaperonin-containing T-complex [20]. This differentiation may stem from fundamental methodological differences: CRISPR generates complete knockout populations, while RNAi produces partial knockdowns that may better tolerate essential gene targeting [20]. Additionally, CRISPR's DNA-level action independent of transcriptional activity may enhance detection of genes with low transcription rates, whereas RNAi efficacy correlates with transcript abundance [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR and RNAi Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA, RNP complexes [2] | Direct DNA cleavage for gene knockout |

| RNAi Triggers | siRNA, shRNA, miRNA mimics/inhibitors [2] | mRNA targeting for gene knockdown |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation [2] | Intracellular delivery of editing components |

| NHEJ Pathway Tools | Ku70/Ku80 inhibitors, Ligase IV inhibitors [23] | Modulate DNA repair pathway choice |

| RNAi Machinery Components | Dicer substrates, RISC components [2] | Enhance RNAi efficiency and specificity |

| Editing Efficiency Assays | T7E1 assay, ICE analysis, NGS validation [2] [23] | Quantify genome editing efficiency |

| Knockdown Validation | qRT-PCR, Western blot, immunofluorescence [2] | Measure reduction in target expression |

| Cell Lines | NHEJ-deficient cells (Ku70, Ku80, LigIV knockouts) [23] | Enhance HDR efficiency for precise editing |

The selection of appropriate reagents significantly influences experimental outcomes. For CRISPR studies, the format of editing components affects both efficiency and specificity. Plasmid-based expression systems offer convenience but may increase off-target effects, while synthetic ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes provide immediate activity, reduced off-target effects, and higher editing efficiency [2]. For RNAi experiments, chemically modified siRNAs with improved stability and reduced immunostimulation have enhanced reproducibility compared to early generation reagents. The development of NHEJ-deficient cell lines through knockout of key pathway components (Ku70, Ku80, LigIV, XRCC4, XLF) has provided valuable tools for enhancing homology-directed repair efficiency, with studies demonstrating up to 7-fold improvement in precise editing outcomes [23].

The comparative analysis of cellular repair pathways in CRISPR-Cas9 and endogenous RNAi machinery reveals two technologically distinct approaches with complementary strengths. The NHEJ-mediated CRISPR knockout system provides permanent, complete gene disruption at the DNA level, making it ideal for studies requiring absolute gene ablation and identification of essential genetic elements [2] [20]. In contrast, the endogenous RNAi pathway enables reversible, titratable gene suppression at the mRNA level, offering advantages for studying essential genes and achieving partial loss-of-function phenotypes [2].

Strategic selection between these technologies should be guided by experimental objectives rather than perceived technological superiority. CRISPR excels in comprehensive functional genomics screens, therapeutic applications requiring permanent correction, and situations demanding complete protein ablation [2] [8]. RNAi remains valuable for studying dose-dependent gene effects, validating candidate genes, and manipulating gene expression in sensitive systems where DNA damage response would be detrimental [2] [20]. Notably, combined implementation of both technologies provides superior biological insight, as evidenced by improved performance metrics (AUC 0.98) when integrating data from parallel CRISPR and RNAi screens [20].

Future directions will likely emphasize integrated approaches that leverage the unique advantages of each technology while addressing their limitations through continued innovation. Base editing and prime editing technologies already offer more precise genetic modifications without relying on NHEJ, while enhanced RNAi platforms with reduced off-target effects maintain the reversibility and titratability crucial for many applications [8]. For researchers pursuing functional genomics and therapeutic development, the strategic combination of CRISPR and RNAi technologies, informed by their distinct cellular repair pathways, will continue to accelerate biological discovery and therapeutic innovation.

The specificity of CRISPR and RNAi (RNA interference) technologies is governed by distinct and inherent molecular mechanisms. CRISPR systems achieve DNA-level targeting through a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence that must flank the target site for recognition by Cas proteins [24] [25]. In contrast, RNAi operates at the mRNA level through the seed region, a 6-8 nucleotide segment at the 5' end of the small RNA guide that is the primary determinant for target binding [4]. These fundamental recognition rules create different specificity profiles and experimental constraints for each technology. This guide provides an objective comparison of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform their application in research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Specificity Determinants

Table 1: Core Characteristics of PAM Sequences and Seed Regions

| Feature | CRISPR PAM Sequence | RNAi Seed Region |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Nature | Short DNA sequence (typically 2-5 bp) in the target DNA [25] | 6-8 nucleotide segment at the 5' end of the small RNA guide (e.g., siRNA, miRNA) [4] |

| Primary Function | Enables self/non-self discrimination; initiates DNA interrogation by Cas effector proteins [24] [26] | Serves as the primary determinant for target mRNA recognition and binding by the RISC complex [4] |

| Location | Flanks the protospacer in the target DNA (5' or 3' depending on Cas protein) [24] [27] | Located within the guide RNA itself (nucleotides 2-8 of the antisense strand) [4] |

| Impact on Target Range | Restricts targetable genomic sites; a nuclease with an NGG PAM can target ~1 in 8 bases in DNA [26] | Does not restrict targetable genes, but dictates a profile of potential off-target mRNAs via seed matching [4] |

| Consequence of Absence | Perfectly complementary targets without a PAM are completely ignored by Cas nuclease [26] | Target mRNA binding is inefficient or does not occur |

| Common Off-Target Effects | Sequence-dependent cleavage at genomic sites with similar protospacer and a PAM [2] | Widespread, miRNA-like silencing of dozens to hundreds of transcripts with complementary seed matches [4] |

Table 2: Experimentally Observed Specificity Profiles

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 | RNAi (shRNA) |

|---|---|---|

| On-Target Efficacy | Highly effective at generating gene knockouts [2] [4] | Effective at reducing mRNA transcript levels (knockdown) [2] [4] |

| Prevalence of Systematic Off-Targets | Lower susceptibility to systematic off-target effects; off-targets are more predictable and manageable through gRNA design [4] | High and pervasive; a larger component of gene expression changes is often a consequence of the seed sequence rather than on-target knockdown [4] |

| Correlation of Signatures (CMAP Data) | Signatures from the same sgRNA correlate, while different sgRNAs do not [4] | Strong correlation between reagents sharing a seed sequence, often stronger than correlation between reagents targeting the same gene [4] |

| Primary Confounding Factor in Screens | Toxicity from a large number of non-specific DNA cuts by low-specificity gRNAs [28] | Seed-based off-target effects can silence numerous non-target genes, leading to erroneous phenotypic conclusions [4] |

Visualizing Core Recognition Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental target recognition pathways for CRISPR and RNAi technologies, highlighting the roles of the PAM and seed region.

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Evidence

Assessing RNAi Seed-Based Off-Target Effects

Objective: To quantify the pervasive off-target effects in RNAi resulting from the seed sequence mechanism [4].

Methodology:

- Dataset Construction: Analyze gene expression signatures from the Connectivity Map (CMAP) comprising over 13,000 shRNAs profiled across 9 human cell lines [4].

- Signature Correlation: Calculate pairwise correlations between gene expression signatures from different shRNAs. Two comparison classes are established:

- Same-Gene Pairs: shRNAs with different seed sequences that target the same gene.

- Same-Seed Pairs: shRNAs designed to target different genes but which share the same 7-nucleotide seed sequence.

- Holdout Validation: Apply a holdout method for genes targeted by ≥6 shRNAs. Disjoint groups of shRNAs are used to generate independent Consensus Gene Signatures (CGS), which are then correlated to evaluate the fidelity of the inferred on-target signature [4].

- Data Analysis: Compare the distribution of correlation coefficients for same-gene pairs versus same-seed pairs against a null distribution of all possible pairwise correlations.

Key Findings:

- shRNAs sharing the same seed sequence showed a significantly stronger correlation in their gene expression signatures than shRNAs targeting the same gene but having different seeds [4].

- This indicates that a larger component of the transcriptional response to an shRNA is determined by its seed sequence rather than the knockdown of its intended target [4].

- Reliance on a single shRNA for phenotypic assessment is highly prone to error due to these pervasive seed-driven effects [4].

Evaluating CRISPR-Cas9 Specificity and PAM Role

Objective: To determine the role of the PAM in ensuring efficient on-target editing and to compare the specificity of CRISPR to RNAi [29] [4].

Methodology:

- Comparative Analysis: Analyze gene expression signatures from 373 single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) across 6 cell lines from the CMAP dataset and compare the profile to the RNAi data [4].

- Specificity Assessment: Examine correlations between biological replicates of the same sgRNA and between different sgRNAs to assess reproducibility and the absence of systematic off-target transcriptional signatures [4].

- Biochemical Investigation (Two-Step Capture): Use biochemical, biophysical, and cell-based assays on Cas9 variants with different PAM-binding specificities.

- Measure kinetics of DNA binding and unwinding.

- Assess how reduced PAM specificity (broadened PAM recognition) affects non-selective DNA binding and the efficiency of stable R-loop formation [29].

- Editing Efficiency Measurement: Quantify genome-editing efficiency in cells for the different Cas9 variants to correlate PAM specificity with functional outcomes [29].

Key Findings:

- CRISPR-Cas9 demonstrates significantly lower susceptibility to systematic off-target effects compared to RNAi, with on-target efficacies being comparable between the technologies [4].

- There is a fundamental trade-off between PAM recognition breadth and editing effectiveness. Variants with overly relaxed PAM requirements suffer from persistent non-selective DNA binding and recurrent failure to engage the correct target, leading to reduced editing efficiency [29].

- High-efficiency editing relies on an optimized two-step target capture: selective (but low-affinity) PAM binding followed by rapid DNA unwinding and R-loop formation [29].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Specificity-Driven Experiments

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GuideScan2 Software [28] | A computational tool for genome-wide design and specificity analysis of CRISPR gRNAs. Uses a novel algorithm to enumerate off-targets and score gRNA specificity accurately. | Designing high-specificity gRNA libraries for knockout (CRISPRko), interference (CRISPRi), or activation (CRISPRa) screens to minimize off-target confounders. |

| Consensus Gene Signature (CGS) [4] | A computational method to generate a weighted average gene expression signature from multiple shRNAs (with different seeds) targeting the same gene. | Mitigating RNAi seed-based off-target effects in transcriptomic analyses to derive a more reliable on-target signature. |

| PAM-SCANR Assay [25] | A high-throughput in vivo method (PAM screen achieved by NOT-gate repression) using dCas9 to identify functional PAM sequences for a given Cas protein. | Characterizing the PAM preferences of novel or engineered Cas nucleases. |

| High-Specificity gRNA Library [28] | A ready-to-use library (e.g., from GuideScan2) designed with six high-specificity gRNAs per gene, plus control gRNAs. | Performing genome-wide CRISPR screens with reduced off-target effects and minimal confounding fitness signals. |

| RNP Complex (Ribonucleoprotein) [2] | A preassembled complex of synthetic guide RNA and purified Cas9 protein. | CRISPR delivery format that promotes high editing efficiency and reduces off-target effects by shortening the exposure time of genomic DNA to the nuclease. |

| Artificial miRNAs (amiRNAs) [30] | Designed miRNAs expressed from a Pol II promoter within a natural miRNA scaffold (e.g., miR-30) to target specific RNA sequences. | Used in conjunction with enhancers like enoxacin to quantitatively inhibit CRISPR function or to study specific RNAi effects. |

Discussion and Research Implications

The inherent specificity mechanisms of CRISPR and RNAi present a clear trade-off for researchers. The PAM requirement of CRISPR imposes a targeting constraint but, in doing so, enforces a high barrier to action that results in fewer systematic off-targets and more reliable genetic screens [2] [4]. Conversely, the seed-based targeting of RNAi offers theoretical flexibility but introduces pervasive and potent miRNA-like off-target effects that can confound phenotypic interpretation [4]. The choice between technologies therefore depends heavily on the experimental question.

For definitive loss-of-function studies requiring high confidence in genotype-phenotype relationships, CRISPR is often the superior tool. However, for studies of essential genes where complete knockout is lethal, or where transient and reversible silencing is desired, RNAi remains valuable, provided that rigorous controls—such as using multiple shRNAs with different seeds and employing Consensus Gene Signatures for transcriptomic analysis—are implemented [2] [4]. Future directions in CRISPR engineering aim to relax the PAM constraint without sacrificing efficiency [26], while advances in RNAi focus on better understanding and controlling for seed-based effects. For both, the development of sophisticated design tools like GuideScan2 and analytical methods like CGS is critical for empowering researchers to generate more reliable and interpretable data [28] [4].

Choosing Your Tool: Experimental Workflows and Application-Specific Use Cases

This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of CRISPR and RNAi experimental workflows, from initial design to final validation. Understanding these distinctions is critical for selecting the optimal gene silencing method for your research, particularly in drug discovery and functional genomics.

CRISPR and RNAi are powerful technologies for probing gene function, but they operate through fundamentally distinct biochemical mechanisms, which in turn dictate their experimental workflows and outcomes.

RNAi (RNA Interference): This technology achieves gene knockdown by degrading or blocking the translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) in the cytoplasm. It utilizes the cell's native RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Introduced double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is processed by the Dicer enzyme into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or microRNAs (miRNAs), which guide RISC to complementary mRNA sequences for cleavage or translational inhibition [2]. Its effects are transient and reversible.

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) - Cas9: This technology typically creates a gene knockout by introducing permanent, targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in genomic DNA. The Cas9 nuclease is directed by a guide RNA (gRNA) to a specific DNA sequence. The cell's repair of this break via the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the gene's coding sequence [2]. Its effects are generally permanent.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms and the consequent high-level workflows for each technology.

Performance and Efficiency Comparison

Systematic comparisons and large-scale screens reveal significant differences in the performance of CRISPR and RNAi technologies, particularly regarding their efficacy and false positive rates.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CRISPR and RNAi from Functional Genomic Screens

| Performance Metric | CRISPR-Cas9 | RNAi | Supporting Data & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-Target Efficacy | High; achieves complete gene knockout [20]. | Variable; produces partial gene knockdown, efficacy is reagent-dependent [20]. | Both screens in K562 cells showed high performance (AUC >0.90) in detecting essential genes [20]. |

| Off-Target Effects | Generally lower and more manageable [3]. Susceptible to sequence-specific DNA off-targets, but improved gRNA design and modified sgRNAs reduce this [2]. | High and pervasive [3]. Dominated by miRNA-like seed-based off-target effects, silencing hundreds of unintended transcripts [3]. | Large-scale gene expression profiling found RNAi's off-target effects are "far stronger and more pervasive than generally appreciated" [3]. |

| Correlation Between Technologies | Low correlation with RNAi screen results [20]. | Low correlation with CRISPR screen results [20]. | A 2016 study found ~1,200 essential genes identified by both, but ~4,500 unique to CRISPR and ~3,100 unique to RNAi [20]. |

| Identification of Biological Processes | Can identify distinct essential biological processes (e.g., electron transport chain) [20]. | Can identify distinct essential biological processes (e.g., chaperonin-containing T-complex) [20]. | Combining data from both screens using a statistical framework (casTLE) improved identification of essential genes and biological terms [20]. |

| Performance by Gene Expression Level | Strong performance for highly expressed essential genes [31]. | Outperforms CRISPR for identifying lowly expressed essential genes; strong performance for highly expressed genes [31]. | A 2024 analysis of 254 cell lines showed shRNA's superior performance for low-expression genes. Combining both platforms is suggested for high-expression genes [31]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section details the standard protocols for executing loss-of-function experiments using both CRISPR and RNAi.

RNAi Experimental Workflow

The RNAi workflow focuses on designing and delivering RNA molecules that harness the cell's endogenous machinery to silence target mRNA.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNAi

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| siRNA (synthetic) or shRNA (expressed) | The effector molecule; a designed double-stranded RNA that is processed and loaded into RISC to guide target mRNA recognition. |

| Dicer Enzyme | An endogenous endoribonuclease that processes long dsRNA or pre-shRNA into short, ~21 nucleotide siRNAs. |

| RISC (RNA-induced Silencing Complex) | The endogenous multi-protein complex that uses the siRNA guide strand to identify and cleave complementary mRNA targets. |

| Transfection Reagents / Viral Vectors | Methods for delivering synthetic siRNAs or shRNA-encoding plasmids/vectors into the target cells. |

| Quantitative RT-PCR Assay | The standard method for validating the success of the experiment by quantifying the reduction in target mRNA levels. |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Design and Selection: Design highly specific siRNAs or shRNAs that target only the intended gene sequence. Tools are used to minimize off-target effects, though this remains challenging [2].

- Delivery: Introduce the designed siRNA (synthetic) or shRNA (via plasmid vectors, PCR products, or in vitro transcription) into the target cells. A key advantage is that mammalian cells possess the endogenous Dicer and RISC machinery, so few external components need delivery [2].

- Gene Silencing: Inside the cell, the dsRNA is processed by Dicer and loaded into RISC. The complex binds to and cleaves or sterically blocks the target mRNA, preventing its translation into protein [2].

- Validation: Measure the efficiency of gene silencing 24-72 hours post-delivery. This is typically done by:

- Quantifying mRNA transcript levels using quantitative RT-PCR.

- Measuring protein levels using immunoblotting (Western blot) or immunofluorescence.

- Monitoring associated phenotypic changes [2].

CRISPR-Cas9 Experimental Workflow

The CRISPR workflow involves the delivery of a custom guide RNA and the Cas9 nuclease to create targeted, permanent changes to the genome.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | The targeting component; a chimeric RNA molecule that combines tracerRNA and crRNA functions to direct Cas9 to a specific genomic locus. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | The effector protein; an endonuclease that creates a double-strand break in the target DNA upon gRNA binding. |

| Repair Template (for HDR) | An exogenous DNA template used to introduce specific point mutations or insertions via the Homology-Directed Repair pathway. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | A pre-formed complex of gRNA and Cas9 protein. Delivery of RNP complexes increases editing efficiency and reduces off-target effects [2]. |

| ICE Analysis Software | A bioinformatics tool (Inference of CRISPR Edits) used to analyze Sanger sequencing data from edited cell populations and quantify editing efficiency [2]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- gRNA Design and Synthesis: Design efficient and specific guide RNAs using state-of-the-art design tools. This is a critical step for success and minimizing off-target activity [2].

- Delivery of CRISPR Components: Choose a delivery format for the gRNA and Cas9 nuclease. While transfecting plasmids is common, the availability of high-quality synthetic gRNA allows for the formation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. The RNP format is now the preferred choice for many researchers as it enables the highest editing efficiencies and reproducibility [2].

- Genome Editing and Repair: The gRNA directs Cas9 to the target DNA sequence, where it induces a double-strand break. The cell repairs this break via the error-prone NHEJ pathway, leading to insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the gene and create a knockout [2].

- Validation and Analysis: Analyze editing efficiency 2-7 days post-delivery. This can be done by:

- Using tools like ICE to analyze Sanger sequencing data from a mixed population of cells.

- Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) analysis.

- Sanger sequencing of isolated clonal lines to confirm biallelic knockout.

- Measuring protein loss via Western blot to confirm functional knockout [2].

Application in Genetic Screening and Validation

Both technologies are widely used in high-throughput genetic screening, but their performance and optimal use cases differ.

High-Throughput Screening: Prior to CRISPR, RNAi libraries were the standard for genome-wide loss-of-function screens. However, RNAi screens have been historically plagued by poor reproducibility due to high off-target effects, leading to high false positive rates [2] [3]. CRISPR has now emerged as a primary tool for target identification and validation in pooled screens due to its higher specificity and ability to create complete knockouts [2] [32]. A typical pooled CRISPR screen involves introducing a library of gRNAs into a large pool of Cas9-expressing cells, applying a biological challenge (e.g., drug treatment), and then sequencing the gRNAs to identify哪些genes whose loss confers sensitivity or resistance [32].

Validation of Screening Hits: The low correlation between hits identified in CRISPR and RNAi screens suggests that they can capture distinct biological insights [20]. Therefore, a powerful strategy is to validate screening hits using the alternative technology. A hit from a primary CRISPR screen can be confirmed using RNAi-mediated knockdown, and vice-versa. This orthogonal validation helps control for technology-specific artifacts and false positives [20]. Furthermore, combination analysis frameworks like casTLE (Cas9 high-Throughput maximum Likelihood Estimator) have been developed to integrate data from both CRISPR and RNAi screens, resulting in a more robust identification of true essential genes and biological pathways [20].

The choice between CRISPR and RNAi is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific biological question and experimental context.

CRISPR-Cas9 is generally the preferred method for achieving complete and permanent gene knockout, especially in applications where high specificity and definitive loss-of-function are required, such as in functional genomic screens and disease modeling. Its primary drawbacks are the potential for longer experimental timelines (particularly for generating clonal knockout lines) and greater complexity in delivery [33].

RNAi remains a valuable tool for studying the effects of partial, transient gene knockdown. It is particularly useful for investigating essential genes, where complete knockout would be lethal, or for performing rapid, reversible functional studies. Its major limitation is the high prevalence of off-target effects, which necessitates careful controls and validation [2] [3].

Emerging technologies like CRISPRi (which uses a dead Cas9 to block transcription without cutting DNA) and AI-designed editors like OpenCRISPR-1 are further expanding the toolbox, offering new possibilities for gene modulation with potentially enhanced properties [2] [34]. For the most comprehensive and robust results, particularly in high-stakes drug discovery and development, a combination of both CRISPR and RNAi technologies often provides the most stringent validation and deepest biological insight [20] [31].

The comparison between Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and RNA interference (RNAi) represents a fundamental consideration in genetic research methodology. While both techniques enable gene silencing, they operate through fundamentally distinct mechanisms: CRISPR generates permanent knockouts at the DNA level, whereas RNAi produces temporary knockdowns at the mRNA level [2]. This mechanistic difference dictates their optimal applications in research and therapeutic development.