Evaluating Sensitivity and Specificity in Functional Assays: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Research and Development

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of functional assays.

Evaluating Sensitivity and Specificity in Functional Assays: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of functional assays. It covers foundational principles, practical methodologies, advanced troubleshooting for optimization, and rigorous validation protocols. By integrating theoretical knowledge with actionable strategies, this guide aims to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and regulatory compliance of assays used in drug discovery, diagnostics, and clinical research.

Core Principles: Defining Sensitivity and Specificity in a Functional Context

Understanding Diagnostic vs. Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

In the field of research and drug development, the terms "sensitivity" and "specificity" are fundamental metrics for evaluating assay performance. However, their meaning shifts significantly depending on whether they are used in an analytical or diagnostic context. This distinction is not merely semantic but represents a fundamental difference in what is being measured: the technical capability of an assay versus its real-world effectiveness in classifying samples. Analytical performance focuses on an assay's technical precision under controlled conditions, specifically its ability to detect minute quantities of an analyte (sensitivity) and to distinguish it from interfering substances (specificity) [1] [2]. In contrast, diagnostic performance evaluates the assay's accuracy in correctly identifying individuals with a given condition (sensitivity) and without it (specificity) within a target population [1] [3].

Confusing these terms can lead to significant errors in test interpretation, assay selection, and ultimately, decision-making in the drug development pipeline. A test with exquisite analytical sensitivity may be capable of detecting a single molecule of a target analyte, yet still perform poorly as a diagnostic tool if the target is not a definitive biomarker for the disease in question [1] [4]. Therefore, researchers and scientists must always qualify these terms with the appropriate adjectives—"analytical" or "diagnostic"—to ensure clear communication and accurate assessment of an assay's capabilities and limitations [2].

Conceptual Comparison: Analytical vs. Diagnostic

The core difference between analytical and diagnostic measures lies in their focus and application. The following table provides a concise comparison of these concepts:

| Feature | Analytical Sensitivity & Specificity | Diagnostic Sensitivity & Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Technical performance of the assay itself [1] | Accuracy in classifying a patient's condition [1] |

| Context | Controlled laboratory conditions [1] | Real-world clinical or preclinical population [1] [5] |

| What is Measured | Detection and discrimination of an analyte [2] | Identification of presence or absence of a disease/condition [3] |

| Key Question | "Can the assay reliably detect and measure the target?" | "Can the test correctly identify sick and healthy individuals?" [3] |

| Impact of Result | Affects accuracy and precision of quantitative data. | Directly impacts false positives/negatives and predictive value [6]. |

The Inverse Relationship and the Trade-Off

In the realm of diagnostic testing, sensitivity and specificity often exist in an inverse relationship [6]. Modifying a test's threshold to increase its sensitivity (catch all true positives) typically reduces its specificity (introduces more false positives), and vice versa [5] [3]. This trade-off is a critical consideration in both medical diagnostics and preclinical drug development.

In preclinical models, for example, this trade-off can be "dialed in" by setting a specific threshold on the model's quantitative output [5]. A model could be tuned for perfect sensitivity (flagging all toxic drugs) but at the cost of misclassifying many safe drugs as toxic (low specificity). Conversely, a model can be tuned for perfect specificity (never misclassifying a safe drug as toxic), which may slightly reduce its sensitivity [5]. The optimal balance depends on the context: for a serious disease with a good treatment, high sensitivity is prioritized to avoid missing cases; for a condition where a false positive leads to invasive follow-up, high specificity is key [3].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Comparison

The evaluation of analytical and diagnostic parameters requires distinct experimental approaches and yields different types of data. The following table summarizes the key performance indicators, their definitions, and how they are determined experimentally.

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Experimental Protocol & Data Output |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity (LoD) | The smallest amount of an analyte in a sample that can be accurately measured [1] [7]. | Protocol: Test multiple replicates (e.g., 20 measurements) of samples at different concentrations, including levels near the expected detection limit [7]. Output: A specific concentration (e.g., 0.1 ng/mL) representing the lowest reliably detectable level [7]. |

| Analytical Specificity | The ability of an assay to measure only the intended analyte without cross-reactivity or interference [1]. | Protocol: Conduct interference studies using specimens spiked with potentially cross-reacting analytes or interfering substances (e.g., medications, endogenous substances) [1] [7]. Output: A list of substances that do or do not cause cross-reactivity or interference, often reported as a percentage [1]. |

| Diagnostic Sensitivity | The proportion of individuals with a disease who are correctly identified as positive by the test [6] [3]. | Protocol: Perform the test on a cohort of subjects with confirmed disease (via a gold standard method) and calculate the proportion testing positive [8]. Output: A percentage (e.g., 99.2%) derived from: TP / (TP + FN) [8]. |

| Diagnostic Specificity | The proportion of individuals without a disease who are correctly identified as negative by the test [6] [3]. | Protocol: Perform the test on a cohort of healthy subjects (confirmed by gold standard) and calculate the proportion testing negative [8]. Output: A percentage (e.g., 83.1%) derived from: TN / (TN + FP) [8]. |

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Determining Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection)

Establishing the Limit of Detection (LoD) for an assay is a rigorous process. A best practice approach involves:

- Replicate Testing: Perform a minimum of 20 independent measurements at, above, and below the suspected LoD [7]. This provides a robust statistical basis for the calculation.

- Appropriate Controls: For molecular assays involving nucleic acid extraction, a control must be included to monitor the efficiency of the extraction process itself. Using whole organisms (e.g., bacteria or viruses) as control material is recommended to challenge the entire workflow from extraction to detection [7].

- Data Analysis: The LoD is determined as the lowest concentration at which ≥95% of the replicates test positive, confirming consistent and reliable detection at that level.

Establishing Analytical Specificity

Evaluating analytical specificity involves testing the assay's resilience to interference and cross-reactivity.

- Interference Studies: Test specimens spiked with high concentrations of potential interfering agents against non-spiked specimens. Interferents can include endogenous substances (like lipids or bilirubin), exogenous substances (common medications), or substances from sample collection (e.g., powdered gloves) [1] [7].

- Cross-Reactivity Panels: Assess a panel of genetically or structurally related organisms or analytes to identify potential sources of false-positive results. For example, an assay for Virus A should be tested against closely related Virus B and Virus C to ensure it does not generate a positive signal [7].

- Matrix Studies: These studies should be conducted for each specimen type (e.g., serum, plasma, saliva) that will be used with the assay, as the matrix can influence interference [7].

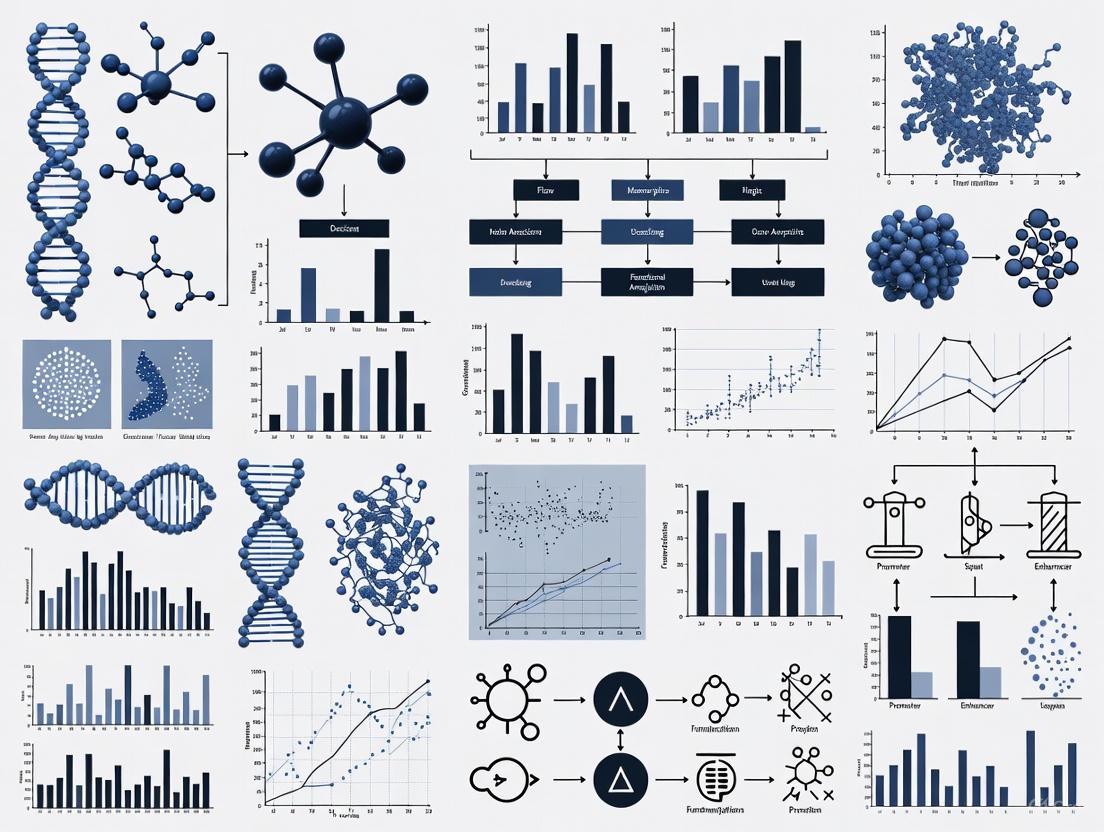

Workflow for Comprehensive Assay Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression and key components involved in characterizing both the analytical and diagnostic performance of an assay, highlighting their distinct roles in the development pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and tools required for the rigorous validation of sensitivity and specificity in assay development.

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized materials with known analyte concentrations, essential for calibrating instruments and establishing a standard curve for quantitative assays. |

| Linear/Performance Panels | Commercially available panels of samples across a range of concentrations, used to determine linearity, analytical measurement range, and Limit of Detection (LoD) [7]. |

| Cross-Reactivity Panels | Panels containing related but distinct organisms or analytes, critical for testing and demonstrating the analytical specificity of an assay [7]. |

| ACCURUN-type Controls | Third-party controls that are typically whole-organism or whole-cell, used to appropriately challenge the entire assay workflow from extraction to detection, verifying performance [7]. |

| Interference Kits | Standardized kits containing common interfering substances (e.g., bilirubin, hemoglobin, lipids) to systematically evaluate an assay's susceptibility to interference [7]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Systems like the I.DOT liquid handler automate liquid dispensing, improving precision, minimizing human error, and enhancing the reproducibility of validation data [9]. |

A clear and unwavering distinction between analytical and diagnostic sensitivity and specificity is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals. Analytical metrics define the technical ceiling of an assay in a controlled environment, while diagnostic metrics reveal its practical utility in the messy reality of biological populations. Understanding that a high analytical sensitivity does not automatically confer a high diagnostic sensitivity is a cornerstone of robust assay development and interpretation [1]. The strategic "dialing in" of the sensitivity-specificity trade-off, guided by the specific context of use—whether to avoid missing a toxic drug candidate or to prevent the costly misclassification of a safe one—is a critical skill [5]. By adhering to best practices in experimental validation and leveraging the appropriate tools and controls, scientists can generate reliable, meaningful data that accelerates the drug development pipeline and ultimately leads to safer and more effective therapeutics.

The Critical Role of a Gold Standard in Assay Validation

In the rigorous world of diagnostic and functional assay development, the gold standard serves as the critical benchmark against which all new tests are measured. Often characterized as the "best available" reference method rather than a perfect one, this standard constitutes what has been termed an "alloyed gold standard" in practical applications [10]. The validation of any new assay relies fundamentally on comparing its performance—typically measured through sensitivity (ability to correctly identify true positives) and specificity (ability to correctly identify true negatives)—against this reference point [10]. When developing tests to detect a condition of interest, researchers must measure diagnostic accuracy against an existing gold standard, with the implication that sensitivity and specificity are inherent attributes of the test itself [10].

The process of assay validation comprehensively demonstrates that a test is fit for its intended purpose, systematically evaluating every aspect to ensure it provides accurate, reliable, and meaningful data [11]. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), validation establishes "the reliability and relevance of a particular approach, method, process or assessment for a defined purpose" [12]. This process is particularly crucial in biomedical fields, where validated assays provide the reliable data needed for informed clinical decisions [11].

The Imperfect Reality: "Alloyed" Gold Standards and Their Consequences

Theoretical Framework of Imperfect Reference Standards

Despite their critical role, gold standards are frequently imperfect in practice, with sensitivity or specificity less than 100% [10]. This imperfection can significantly impact conclusions about the validity of tests measured against it. Foundational work by Gart and Buck (1966) demonstrated that assuming a gold standard is perfect when it is not can dramatically perturb estimates of diagnostic accuracy [10]. They showed formally that when a reference test used as a gold standard is imperfect, observed rates of co-positivity and co-negativity can vary markedly with disease prevalence [10].

The terminology of "gold standard" should be understood to mean that the standard is "the best available" rather than perfect [10]. In reality, no test is inherently perfect, and regulatory agencies have come to accept data from various model systems despite acknowledging inherent shortcomings [12]. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines validation as "assessing [an] assay and its measurement performance characteristics [and] determining the range of conditions under which the assay will give reproducible and accurate data" [12].

Quantitative Impact on Measured Specificity

Recent simulation studies examining the impact of imperfect gold standard sensitivity on measured test specificity reveal striking effects, particularly at different levels of condition prevalence [10]. When gold standard sensitivity decreases, researchers observe increasing underestimation of test specificity, with the extent of underestimation magnified at higher prevalence levels [10].

Table 1: Impact of Imperfect Gold Standard Sensitivity on Measured Specificity

| Death Prevalence | Gold Standard Sensitivity | True Test Specificity | Measured Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 98% | 99% | 100% | <67% |

| High (>90%) | 90-99% | 100% | Significantly suppressed |

| 50% | 90% | 100% | Minimal suppression |

This phenomenon was demonstrated in real-world oncology research using the National Death Index (NDI) as a gold standard for mortality endpoints [10]. The NDI aggregates death certificates from all U.S. states, representing the most complete source of certified death information, yet still suffers from imperfect sensitivity due to delays in death reporting and processing [10]. At 98% death prevalence, even near-perfect gold standard sensitivity (99%) resulted in suppression of specificity from the true value of 100% to a measured value of <67% [10].

The following diagram illustrates how an imperfect gold standard affects validation outcomes:

Statistical Correction Methods for Imperfect Reference Standards

When confronting an imperfect gold standard, researchers have developed several statistical correction methods to estimate the true sensitivity and specificity of a new test. The most prominent approaches include:

- Gart and Buck Correction Method: Uses algebraic functions to adjust estimates based on known sensitivity and specificity of the imperfect reference standard [13]

- Staquet et al. Correction Method: Equivalent to the Gart and Buck approach, providing estimators for when the index test and reference standard are conditionally independent [13]

- Brenner Correction Method: Offers estimators for both conditionally independent and dependent scenarios [13]

These "correction methods" aim to correct the estimated sensitivity and specificity of the index test using available information about the imperfect reference standard via algebraic functions, without requiring probabilistic modeling like latent class models [13].

Comparative Performance of Correction Methods

Simulation studies comparing these correction methods reveal distinct performance characteristics under different conditions:

Table 2: Comparison of Statistical Correction Methods for Imperfect Gold Standards

| Method | Key Assumption | Performance Under Ideal Conditions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staquet et al. | Conditional independence | Outperforms Brenner method | Produces illogical results (outside [0,1]) with very high (>0.9) or low (<0.1) prevalence |

| Brenner | Conditional independence | Good performance | Outperformed by Staquet et al. under most conditions |

| Both Methods | Conditional dependence | Fail to estimate accurately when covariance terms not near zero | Require alternative approaches like latent class models |

Under the assumption of conditional independence, the Staquet et al. correction method generally outperforms the Brenner correction method, regardless of disease prevalence and whether the performance of the reference standard is better or worse than the index test [13]. However, when disease prevalence is very high (>0.9) or low (<0.1), the Staquet et al. method can produce illogical results outside the [0,1] range [13]. When tests are conditionally dependent, both methods fail to accurately estimate sensitivity and specificity, particularly when covariance terms between the index test and reference standard are not close to zero [13].

Case Study: Functional Assays for BRCA1 Variant Classification

Experimental Framework and Validation Protocol

The application of rigorous validation principles is exemplified in functional assays for classifying BRCA1 variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Women who inherit inactivating mutations in BRCA1 face significantly increased risks of early-onset breast and ovarian cancers, making accurate variant classification critical for clinical management [14]. The integration of functional data has emerged as a powerful approach to determine whether missense variants lead to loss of function [15].

In one comprehensive study, researchers collected, curated, and harmonized functional data for 2,701 missense variants representing 24.5% of possible missense variants in BRCA1 [15]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Literature Curation and Data Extraction: Annotating all published functional data for BRCA1 missense variants, with specific assay instances tracked as "tracks" [15]

- Data Harmonization: Converting diverse experimental data into binary categorical variables (functional impact versus no functional impact) to enable cross-study comparison [15]

- Reference Panel Establishment: Using a stringent reference panel combining data from the ENIGMA consortium and ClinVar to assess track accuracy [15]

- Evidence Integration: Applying American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) variant interpretation guidelines to assign evidence criteria [15]

The following workflow diagrams the functional assay validation process:

Validation Outcomes and Performance Metrics

The functional assay validation demonstrated exceptional performance characteristics. Using a reference panel of known variants classified by multifactorial models, the validated assay displayed 1.0 sensitivity (lower bound of 95% confidence interval=0.75) and 1.0 specificity (lower bound of 95% confidence interval=0.83) [14]. This analysis achieved excellent separation of known neutral and pathogenic variants [14].

The integration of data from validated assays provided ACMG/AMP evidence criteria for an overwhelming majority of variants assessed: evidence in favor of pathogenicity for 297 variants or against pathogenicity for 2,058 variants, representing 96.2% of current VUS functionally assessed [15]. This approach significantly reduced the number of VUS associated with the C-terminal region of the BRCA1 protein by approximately 87% [14].

Table 3: BRCA1 Functional Assay Validation Results

| Parameter | Result | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 1.0 (95% CI lower bound: 0.75) | Excellent detection of pathogenic variants |

| Specificity | 1.0 (95% CI lower bound: 0.83) | Excellent identification of neutral variants |

| Variants with Evidence | 96.2% of VUS assessed | Dramatic reduction in classification uncertainty |

| VUS Reduction | ~87% decrease in C-terminal region | Significant clinical clarity improvement |

Regulatory Frameworks and Validation Guidelines

International Validation Standards

Formal validation processes have been established across major regulatory jurisdictions to ensure assay reliability and relevance:

United States (ICCVAM): The Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM) was established by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) to address the growing need for obtaining regulatory acceptance of new toxicity-testing methods [12]. ICCVAM evaluates fundamental performance characteristics including accuracy, reproducibility, sensitivity, and specificity [11].

European Union (EURL ECVAM): The European Union Reference Laboratory for Alternatives to Animal Testing (EURL ECVAM) coordinates the independent evaluation of the relevance and reliability of tests for specific purposes at the European level [12].

International (OECD): The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has established formal international processes for validating test methods, creating guidelines for development and adoption of OECD test guidelines [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Assay Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Variants | Benchmarking assay performance against known pathogenic/neutral variants | BRCA1 classification using ENIGMA and ClinVar variants [15] |

| Binary Categorization Framework | Harmonizing diverse data sources into standardized format | Converting functional data to impact/no impact classification [15] |

| Validated Functional Assays | Providing high-quality evidence for variant classification | Transcriptional activation assays for BRCA1 [14] |

| Statistical Correction Methods | Adjusting for imperfect reference standards | Staquet et al. and Brenner methods for accuracy estimation [13] |

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines | Structured framework for evidence integration | Clinical variant classification standards [15] |

The critical role of the gold standard in assay validation cannot be overstated, yet researchers must acknowledge and account for its inherent imperfections. The assumption of a perfect reference standard when validating new tests can lead to significantly biased estimates of sensitivity and specificity, particularly in high-prevalence settings [10]. Through sophisticated statistical correction methods, rigorous validation frameworks like those demonstrated in BRCA1 functional assays, and adherence to international regulatory standards, researchers can navigate the challenges of "alloyed gold standards" to generate reliable, clinically actionable data.

New validation research and review of existing validation studies must consider the prevalence of the conditions being assessed and the potential impact of an imperfect gold standard on sensitivity and specificity measurements [10]. By implementing comprehensive validation programs that encompass both method validation and calibration, laboratories can ensure they generate high-quality data capable of supporting critical research and clinical decisions [11].

Contents

- Core Definitions and Context

- The Confusion Matrix: A Framework for Calculation

- Step-by-Step Calculation Guide

- Advanced Metrics and Threshold Effects

- Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

- Essential Research Toolkit

Core Definitions and Context

In the evaluation of specificity and sensitivity in functional assays, particularly within drug development and biomedical research, the accurate calculation of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) is foundational. These metrics form the basis for assessing the performance of diagnostic tests, classification models, and assays by comparing their outputs against a known reference standard, often termed the "ground truth" or "gold standard" [16] [6]. A deep understanding of these concepts allows researchers to quantify the validity and reliability of their methods, a critical step in translating research findings into clinical applications [6].

The core definitions are as follows:

- True Positive (TP): An instance where the test correctly identifies the presence of a condition or the success of an assay. For example, a diseased patient is correctly classified as diseased, or a successful drug interaction is correctly flagged [16] [3].

- False Positive (FP): An instance where the test incorrectly indicates the presence of a condition when it is objectively absent. This is also known as a Type I error [16] [17]. In a functional assay, this might represent a compound incorrectly identified as active.

- True Negative (TN): An instance where the test correctly identifies the absence of a condition. A healthy patient is correctly classified as healthy, or an inactive compound is correctly identified [16] [3].

- False Negative (FN): An instance where the test fails to detect a condition that is present. This is also known as a Type II error [16] [17]. In research, this could be a therapeutically active compound that the assay fails to detect.

These outcomes are fundamental to deriving essential performance metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, which are prevalence-dependent and crucial for understanding a test's utility in a specific population [6] [3].

The Confusion Matrix: A Framework for Calculation

The confusion matrix, also known as an error matrix, is the standard table layout used to visualize and calculate TP, TN, FP, and FN [18]. It provides a concise summary of the performance of a classification algorithm or diagnostic test. The matrix contrasts the actual condition (ground truth) against the predicted condition (test result).

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure and relationships within a standard binary confusion matrix.

The structure of the confusion matrix allows researchers to quickly grasp the distribution of correct and incorrect predictions. The diagonal cells (TP and TN) represent correct classifications, while the off-diagonal cells (FP and FN) represent the two types of errors [18]. This visualization is critical for identifying whether a test is prone to over-diagnosis (high FP) or under-diagnosis (high FN), enabling targeted improvements in assay design or model training. The terminology is applied consistently across different fields, from clinical medicine to machine learning [16] [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Outcome Terminology Across Domains

| Actual Condition | Predicted/Test Outcome | Outcome Term | Clinical Context | Machine Learning Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Positive | True Positive (TP) | Diseased patient correctly identified | Spam email correctly classified as spam |

| Positive | Negative | False Negative (FN) | Diseased patient missed by test | Spam email incorrectly sent to inbox |

| Negative | Positive | False Positive (FP) | Healthy patient incorrectly flagged | Legitimate email incorrectly marked as spam |

| Negative | Negative | True Negative (TN) | Healthy patient correctly identified | Legitimate email correctly delivered to inbox |

Step-by-Step Calculation Guide

Calculating TP, TN, FP, and FN requires a dataset with known ground truth labels and corresponding test or model predictions. The process involves systematically comparing each pair of results and tallying them into the four outcome categories [18].

1. Experimental Protocol for Data Collection:

- Define Gold Standard: Establish a reliable reference method (e.g., a clinically proven diagnostic test, mass spectrometry confirmation, or expert manual review) to determine the true condition of each sample [6].

- Run Test Method: Apply the new assay or classification model to the same set of samples.

- Record Results: For each sample, record both the result from the gold standard (Actual Condition) and the result from the test method (Predicted Condition).

2. Workflow for Populating the Confusion Matrix: The following workflow diagram outlines the logical decision process for categorizing each sample result into TP, TN, FP, or FN.

3. Worked Calculation Example:

Consider a study evaluating a new blood test for a disease on a cohort of 1,000 individuals [6]. The results were summarized as follows:

- A total of 427 individuals had positive test findings, and 573 had negative findings.

- Out of the 427 with positive findings, 369 actually had the disease.

- Out of the 573 with negative findings, 558 did not have the disease.

To calculate the four core metrics, we first construct the 2x2 confusion matrix.

Table 2: Confusion Matrix for Blood Test Example

| Predicted Condition (Test Result) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Actual Condition (Gold Standard) | Positive | True Positive (TP) = 369 | False Negative (FN) = ? |

| Negative | False Positive (FP) = ? | True Negative (TN) = 558 |

The missing values can be calculated using the row and column totals:

- Total Actual Positives (P): The total number of individuals who truly had the disease. This is not directly given but can be derived. We know from the positive test column that TP = 369. We also know the total number of positive tests is 427.

- False Positives (FP): The number of individuals without the disease who tested positive. FP = Total Positive Tests - TP = 427 - 369 = 58 [6].

- Total Actual Negatives (N): The total number of individuals without the disease. We know TN = 558. We also know the total number of negative tests is 573.

- False Negatives (FN): The number of individuals with the disease who tested negative. FN = Total Negative Tests - TN = 573 - 558 = 15 [6].

- Total Actual Positives (P) confirmed: TP + FN = 369 + 15 = 384.

- Total Actual Negatives (N) confirmed: FP + TN = 58 + 558 = 616.

The completed confusion matrix is shown below.

Table 3: Completed Confusion Matrix for Blood Test Example

| Predicted Condition (Test Result) | Total (Actual) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| Actual Condition (Gold Standard) | Positive | TP = 369 | FN = 15 | P = 384 |

| Negative | FP = 58 | TN = 558 | N = 616 | |

| Total (Predicted) | PP = 427 | PN = 573 | Total = 1000 |

From this matrix, key performance metrics are derived [6] [3]:

- Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN) = 369 / 384 ≈ 0.961 or 96.1%

- Specificity = TN / (TN + FP) = 558 / 616 ≈ 0.906 or 90.6%

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV) = TP / (TP + FP) = 369 / 427 ≈ 0.864 or 86.4%

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV) = TN / (TN + FN) = 558 / 573 ≈ 0.974 or 97.4%

Advanced Metrics and Threshold Effects

The classification threshold is a critical concept that directly influences the values in the confusion matrix. It is the probability cut-off point used to assign a continuous output (e.g., from a logistic regression model) to a positive or negative class [17]. For instance, in spam detection, if an email's predicted probability of being spam is above the threshold (e.g., 0.5), it is classified as "spam"; otherwise, it is "not spam" [17].

Effect of Threshold Adjustment:

- Increasing the Threshold: Makes the test more stringent.

- Fewer False Positives (FP): The test is less likely to incorrectly label a negative as positive.

- Potentially More False Negatives (FN): The test may now miss some true positives that have scores just below the higher threshold.

- Result: Specificity increases, Sensitivity decreases [17].

- Decreasing the Threshold: Makes the test more lenient.

- Fewer False Negatives (FN): The test is more likely to catch true positives.

- Potentially More False Positives (FP): The test may now incorrectly label more negatives as positives.

- Result: Sensitivity increases, Specificity decreases [17].

This trade-off between sensitivity and specificity is inherent to all diagnostic tests and classification systems [19] [3]. The optimal threshold is not always 0.5; it must be chosen based on the relative costs of FP and FN errors in a specific application. For example, in cancer screening, a low threshold might be preferred to minimize FN (missed cancers), even at the cost of more FP (leading to further testing) [17].

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve The ROC curve is a fundamental tool for visualizing the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity across all possible classification thresholds [19]. It plots the True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against the False Positive Rate (1 - Specificity) at various threshold settings.

- The Area Under the Curve (AUC) provides a single metric to evaluate the overall performance of a test. An AUC of 1.0 represents a perfect test, while an AUC of 0.5 represents a test with no discriminative power, equivalent to random guessing [19].

- Researchers use ROC curves to compare different assays or models and to select the optimal operating point (threshold) for their specific needs [19].

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

In the context of evaluating specificity and sensitivity in functional assays, the calculation of the confusion matrix is integrated into rigorous experimental protocols.

Protocol for Assay Validation:

- Sample Preparation: Create a blinded panel of samples with known activity states (e.g., using recombinant proteins, cell lines with known genetic mutations, or compounds with confirmed bioactivity). The "gold standard" should be a well-characterized and orthogonal method [6].

- Assay Execution: Run the functional assay on the entire panel according to standardized operating procedures. Record the raw output data (e.g., fluorescence intensity, cell count, enzymatic rate).

- Data Analysis and Thresholding: Convert raw data into categorical results (Positive/Negative) by applying a pre-defined threshold. This threshold may be established from control samples or using ROC analysis on a training set [19].

- Unblinding and Matrix Construction: Unblind the samples and construct the confusion matrix by comparing the assay's categorical results to the known sample states.

- Performance Calculation: Calculate sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and other relevant metrics (e.g., Likelihood Ratios, Accuracy) from the matrix [6].

Application in High-Throughput Screening (HTS): In drug discovery, HTS assays screen thousands of compounds. The confusion matrix helps quantify the assay's quality. A high rate of false positives leads to wasted resources on follow-up studies, while false negatives mean missing potential drug candidates. Metrics derived from the matrix are used to optimize assay conditions and set hit-selection thresholds that balance sensitivity and specificity [6].

Essential Research Toolkit

The following table details key reagents, tools, and resources essential for conducting research involving the calculation and application of classification metrics.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Assay Evaluation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevance to Specificity/Sensitivity Research |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard Reference Material | Provides the ground truth for sample status (e.g., purified active/inactive compound, genetically defined cell line). | Critical for accurately determining TP, TN, FP, and FN. The validity of all calculated metrics depends on the accuracy of the gold standard [6]. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SciVal) | Used for data analysis, calculation of metrics, generation of confusion matrices, and plotting ROC curves. | Automates the computation of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC. Essential for handling large datasets from high-throughput experiments [19] [20]. |

| Blinded Sample Panels | A set of samples where the experimenter is unaware of the true status during testing to prevent bias. | Ensures the objectivity of the test results, leading to a more reliable and unbiased confusion matrix [6]. |

| Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) & CiteScore | Bibliometric tools for comparing journal impact and influence. | Used by researchers to identify high-quality journals in which to publish findings related to assay validation and diagnostic accuracy [20]. |

| FDA Drug Development Tool (DDT) Qualification Programs | Regulatory pathways for qualifying drug development tools for a specific context of use. | Provides a framework for validating biomarkers and other tools, where demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity is often a key requirement [21]. |

In the realm of diagnostic testing and assay development, sensitivity and specificity are foundational metrics that mathematically describe the accuracy of a test in classifying the presence or absence of a target condition [3]. These metrics are particularly crucial in functional assays research, where evaluating the performance of new detection methods against reference standards is essential for validating their clinical and research utility.

Sensitivity, or the true positive rate, is defined as the probability that a test correctly classifies an individual as 'diseased' or 'positive' when the condition is truly present [22]. It answers the question: "If the condition is present, how likely is the test to detect it?" [3]. Mathematically, sensitivity is calculated as the number of true positives divided by the sum of true positives and false negatives [3] [6]. A test with 100% sensitivity would identify all actual positive cases, meaning there would be no false negatives.

Specificity, or the true negative rate, is defined as the probability that a test correctly classifies an individual as 'disease-free' or 'negative' when the condition is truly absent [22]. It answers the question: "If the condition is absent, how likely is the test to correctly exclude it?" [3]. Mathematically, specificity is calculated as the number of true negatives divided by the sum of true negatives and false positives [3] [6]. A test with 100% specificity would correctly identify all actual negative cases, meaning there would be no false positives.

These metrics are intrinsically linked to the concept of a reference standard (often referred to as a gold standard), which is the best available method for definitively diagnosing the condition of interest [22]. New diagnostic tests or functional assays are validated by comparing their performance against this reference standard, typically using a 2x2 contingency table to categorize results into true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives [23] [22].

The Fundamental Trade-off: Theory and Mechanisms

The inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity represents a core challenge in diagnostic test and assay development [3] [22]. This trade-off means that as sensitivity increases, specificity typically decreases, and vice-versa [6]. This phenomenon is not due to error in test design, but rather an inherent property of classification systems, particularly when distinguishing between conditions based on a continuous measurement.

The primary mechanism driving this trade-off is the positioning of the decision threshold or cutoff point on a continuous measurement scale [24]. Many diagnostic tests, including immunoassays and molecular detection assays, produce results on a continuum. Establishing a cutoff point to dichotomize results into "positive" or "negative" categories forces a balance between the two types of classification errors: false negatives and false positives.

- A highly sensitive test uses a liberal cutoff that minimizes false negatives but accepts more false positives, thereby reducing specificity [3]. This approach is exemplified by a test configured to cast a wide net, ensuring it catches all true cases but also captures some non-cases.

- A highly specific test uses a conservative cutoff that minimizes false positives but accepts more false negatives, thereby reducing sensitivity [3]. This approach is exemplified by a test configured to only identify the most clear-cut cases, missing some true cases but rarely misclassifying non-cases.

This relationship is powerfully summarized by the mnemonics SnNOUT and SpPIN:

- SnNOUT: A highly SeNsitive test, when Negative, rules OUT the disease [22]. This is because the test rarely misses true positive cases.

- SpPIN: A highly SPecific test, when Positive, rules IN the disease [22]. This is because the test rarely misclassifies healthy individuals as positive.

The following diagram illustrates how moving the decision threshold affects the balance between sensitivity and specificity, false positives, and false negatives:

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

The inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity is consistently demonstrated across diverse research domains, from medical diagnostics to machine learning. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from various studies that illustrate this trade-off in practice.

Table 1: Experimental Data Demonstrating Sensitivity-Specificity Trade-offs Across Fields

| Field/Application | Test/Condition | High Sensitivity Scenario | High Specificity Scenario | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Diagnostic Principle | Cut-off Adjustment | Sensitivity: ~91%, Specificity: ~82% | Sensitivity: ~82%, Specificity: ~91% | [3] |

| Medical Diagnostics (IOP) | Intraocular Pressure for Glaucoma | Lower cut-off (e.g., 12 mmHg): High Sensitivity, Low Specificity | Higher cut-off (e.g., 35 mmHg): Low Sensitivity, High Specificity (SpPIN) | [22] |

| Cancer Detection (Liquid Biopsy) | Early-Stage Lung Cancer | Sensitivity: 84%, Specificity: 100% (as reported in one study) | N/A | [24] |

| Machine Learning / Public Health | Model Optimization | Context: High cost of missing disease (e.g., cancer). High Sensitivity prioritized. | Context: High cost of false alarms (e.g., drug side effects). High Specificity prioritized. | [25] |

The data from general diagnostic principles shows a clear inverse correlation, where a configuration favoring one metric (e.g., ~91% sensitivity) results in a lower value for the other (e.g., ~82% specificity), and vice versa [3]. The example of using intraocular pressure (IOP) for glaucoma screening perfectly encapsulates the trade-off. A low cutoff pressure (e.g., 12 mmHg) ensures almost no glaucoma cases are missed (high sensitivity, fulfilling SnNOUT) but incorrectly flags many healthy individuals (low specificity). Conversely, a very high cutoff (e.g., 35 mmHg) means a positive result is almost certainly correct (high specificity, fulfilling SpPIN) but misses many true glaucoma cases (low sensitivity) [22].

Context is critical in interpreting these trade-offs. In cancer detection via liquid biopsy, a reported 84% sensitivity and 100% specificity would be considered an excellent profile for a screening test, as it prioritizes ruling out the disease without generating excessive false positives [24]. The prioritization of sensitivity versus specificity is ultimately a strategic decision based on the consequences of error [25].

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

The development and optimization of functional assays with defined sensitivity and specificity profiles depend on a suite of critical research reagents and methodologies. The selection and quality of these components directly influence the assay's performance, reproducibility, and ultimately, the position of its decision threshold.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Assay Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Assay Development | Impact on Sensitivity & Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Material | Provides the definitive measurement against which the new test is validated; considered the 'truth' for categorizing samples in the 2x2 table [22]. | The validity of the entire sensitivity/specificity analysis depends on the accuracy of the reference standard. An imperfect standard introduces misclassification errors [23]. |

| Well-Characterized Biobanked Samples | Comprise panels of known positive and negative samples used to calibrate the assay and establish initial performance metrics [24]. | Using samples with clearly defined status is crucial for accurately calculating true positive and true negative rates during the assay validation phase. |

| High-Affinity Binding Partners | Includes monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies, aptamers, or receptors that specifically capture and detect the target analyte [24]. | High affinity and specificity reduce cross-reactivity (improving specificity) and enhance the signal from genuine positives (improving sensitivity). |

| Signal Amplification Systems | Enzymatic (e.g., HRP, ALP), fluorescent, or chemiluminescent systems that amplify the detection signal from low-abundance targets. | Directly enhances the ability to detect low levels of analyte, a key factor in improving the analytical sensitivity of an assay. |

| Blocking Agents & Buffer Components | Reduce non-specific binding and background noise in the assay system (e.g., BSA, non-fat milk, proprietary blocking buffers). | Critical for minimizing false positive signals, thereby directly improving the specificity of the assay. |

The experimental protocol for establishing an assay's sensitivity and specificity involves a clear, multi-stage workflow that moves from sample collection and testing to result calculation and threshold optimization, as illustrated below:

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

Sample Collection and Reference Standard Testing: A cohort of subjects is recruited, and each undergoes testing with the reference standard to definitively classify them as either having the condition (Diseased) or not having the condition (Healthy) [22]. This establishes the "true" status for each subject.

Experimental Assay Performance and Measurement: All subjects, regardless of their reference standard status, are then tested using the new experimental assay or diagnostic test. The results from this test are recorded, typically as continuous or ordinal data [23].

Result Categorization (2x2 Table Construction): The results from the reference standard and the experimental test are compared for each subject, and subjects are assigned to one of four categories in a 2x2 contingency table [6] [22]:

- True Positives (TP): Subjects with the condition who test positive on the experimental assay.

- False Negatives (FN): Subjects with the condition who test negative on the experimental assay.

- False Positives (FP): Subjects without the condition who test positive on the experimental assay.

- True Negatives (TN): Subjects without the condition who test negative on the experimental assay.

Metric Calculation: Sensitivity and Specificity are calculated using the values from the 2x2 table [3] [6]:

- Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN)

- Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)

Threshold Optimization and ROC Analysis: If the experimental assay produces a continuous output, steps 3 and 4 are repeated for multiple potential decision thresholds. The resulting pairs of sensitivity and specificity values are plotted to generate a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve [26]. The area under this curve (AUC) provides a single measure of overall test discriminative ability, independent of any single threshold.

Implications for Research and Drug Development

Understanding and strategically managing the sensitivity-specificity trade-off is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals. This balance directly impacts various stages of the pipeline, from initial biomarker discovery to clinical trial enrollment and companion diagnostic development.

In biomarker discovery and validation, the choice between a high-sensitivity or high-specificity assay configuration depends on the intended application. A screening assay designed to identify potential candidates from a large population often prioritizes high sensitivity to minimize false negatives, ensuring few true cases are missed for further investigation [3] [24]. Conversely, a confirmatory assay used to validate hits from a primary screen must prioritize high specificity to minimize false positives, thereby ensuring that only truly promising candidates advance in the costly and resource-intensive drug development pipeline [3].

For patient stratification and clinical trial enrollment, diagnostics with high specificity are crucial. Enrolling patients into a trial based on a biomarker requires high confidence that the biomarker is truly present (SpPIN) to ensure the trial population is homogenous and accurately defined [22]. This increases the statistical power of the trial and the likelihood of demonstrating a true treatment effect. Misclassification due to a low-specificity test can dilute the treatment effect by including biomarker-negative patients, potentially leading to trial failure.

The trade-off also fundamentally influences risk assessment and decision-making. The consequences of false negatives versus false positives differ vastly across contexts [25]. In diseases like cancer, where missing a diagnosis (false negative) can be fatal, high sensitivity is paramount. In contrast, for conditions where a false positive diagnosis may lead to invasive, risky, or expensive follow-up procedures or treatments, high specificity becomes the critical metric [3] [25]. Researchers must quantitatively evaluate this trade-off using tools like the ROC curve to select a threshold that aligns with the clinical and research objectives, a process that is as much strategic as it is statistical [26].

In the evaluation of specificity and sensitivity in functional assays, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) represent critical performance metrics that bridge statistical measurement with clinical and research utility [23]. While sensitivity and specificity describe the inherent accuracy of a test relative to a reference standard, PPV and NPV quantify the practical usefulness of test results in real-world contexts [27] [28]. These predictive values answer fundamentally important questions for researchers and clinicians: When a test yields a positive result, what is the probability that the target condition is truly present? Conversely, when a test yields a negative result, what is the probability that the condition is truly absent? [29] [30]

Unlike sensitivity and specificity, which are considered intrinsic test characteristics, PPV and NPV possess the crucial attribute of being dependent on disease prevalence within the study population [27] [31] [28]. This prevalence dependence creates a dynamic relationship that must be thoroughly understood to properly interpret test performance across different populations and settings. For researchers developing diagnostic assays, appreciating this relationship is essential for designing appropriate validation studies and establishing clinically relevant performance requirements [30].

Defining Key Performance Metrics

Fundamental Definitions and Calculations

The evaluation of diagnostic tests typically begins with a 2×2 contingency table that cross-classifies subjects based on their true disease status (as determined by a reference standard) and their test results [32] [33]. This classification generates four fundamental categories:

- True Positives (TP): Subjects with the disease who test positive

- False Positives (FP): Subjects without the disease who test positive

- False Negatives (FN): Subjects with the disease who test negative

- True Negatives (TN): Subjects without the disease who test negative [32]

From these categories, the key performance metrics are calculated as follows:

- Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN) × 100 [33] [23]

- Specificity = TN / (TN + FP) × 100 [33] [23]

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV) = TP / (TP + FP) × 100 [32] [33] [30]

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV) = TN / (TN + FN) × 100 [32] [33] [30]

- Prevalence = (TP + FN) / (TP + FN + FP + TN) × 100 [31] [30]

Conceptual Distinctions Between Test Characteristics

A critical conceptual distinction exists between sensitivity/specificity and predictive values [23]. Sensitivity and specificity are test-oriented metrics that evaluate the assay's performance against a reference standard. In contrast, PPV and NPV are result-oriented metrics that assess the clinical meaning of a specific test result [28]. This distinction has profound implications for how these statistics are interpreted and applied in research and clinical practice.

Sensitivity and specificity remain constant for a given test regardless of the population being tested (assuming consistent test implementation) because they are calculated vertically in the 2×2 table [30]. Conversely, PPV and NPV fluctuate substantially with changes in disease prevalence because they are calculated horizontally across the 2×2 table [27] [28]. This fundamental difference explains why a test with excellent sensitivity and specificity may perform poorly in certain populations with unusually high or low disease prevalence.

The Mathematical Relationship Between Prevalence and Predictive Values

Formulas Connecting Prevalence to Predictive Values

The mathematical relationship between prevalence, test characteristics, and predictive values can be expressed through Bayesian probability principles [32] [29]. The formulas for calculating PPV and NPV from sensitivity, specificity, and prevalence are:

PPV = (Sensitivity × Prevalence) / [(Sensitivity × Prevalence) + (1 - Specificity) × (1 - Prevalence)] [32] [29]

NPV = [Specificity × (1 - Prevalence)] / [Specificity × (1 - Prevalence) + (1 - Sensitivity) × Prevalence] [32] [29]

These formulas demonstrate mathematically how predictive values are functions of both test performance (sensitivity and specificity) and population characteristics (prevalence) [34]. The relationship can be visualized through the following conceptual diagram:

Conceptual diagram showing how prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity influence PPV and NPV.

Impact of Prevalence Changes on Predictive Values

The direction and magnitude of prevalence's effect on predictive values follow predictable patterns [27] [31] [28]:

- As prevalence increases: PPV increases while NPV decreases

- As prevalence decreases: PPV decreases while NPV increases

This relationship occurs because as a disease becomes more common in a population (higher prevalence), a positive test result is more likely to represent a true positive than a false positive, thereby increasing PPV [31]. Simultaneously, in high-prevalence populations, a negative test result is more likely to represent a false negative than a true negative, thereby decreasing NPV [28]. The inverse relationship applies when prevalence decreases.

The following table demonstrates how prevalence impacts PPV and NPV for a test with 95% sensitivity and 90% specificity:

| Prevalence | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 8.8% | >99.9% |

| 5% | 33.3% | 99.7% |

| 10% | 51.4% | 99.4% |

| 20% | 70.4% | 98.7% |

| 50% | 90.5% | 94.7% |

Table 1: Impact of prevalence on PPV and NPV for a test with 95% sensitivity and 90% specificity [27] [30].

Experimental Evidence and Practical Demonstrations

Case Study: Acetaminophen Toxicity Test

A compelling example of prevalence impact comes from a study of a point-of-care test (POCT) for acetaminophen toxicity [28]. Researchers evaluated the test characteristics across two populations with different prevalence rates:

Population A (6% prevalence):

- Sensitivity: 50%, Specificity: 68%

- PPV: 9%, NPV: 96%

Population B (1% prevalence):

- Sensitivity: 50%, Specificity: 68%

- PPV: 2%, NPV: 99%

This case demonstrates that despite identical sensitivity and specificity, the PPV dropped dramatically from 9% to 2% when prevalence decreased from 6% to 1%, while NPV increased slightly from 96% to 99% [28]. For researchers, this highlights the critical importance of selecting appropriate validation populations that reflect the intended use setting for the assay.

Experimental Protocol for Evaluating Predictive Values

To properly evaluate PPV and NPV in diagnostic assay development, researchers should implement the following methodological protocol:

Define Reference Standard: Establish and document the criterion (gold standard) method that will serve as the reference for determining true disease status [33] [23]. This standard must be applied consistently to all study participants.

Select Study Population: Recruit a representative sample that reflects the spectrum of disease severity and patient characteristics expected in the target use population [33]. The sample size should provide sufficient statistical power for precise estimates.

Blinded Testing: Perform both the index test (new assay) and reference standard test on all participants under blinded conditions where test interpreters are unaware of the other test's results [23].

Construct 2×2 Table: Tabulate results comparing the index test against the reference standard [32] [30].

Calculate Metrics: Compute sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and prevalence with corresponding confidence intervals [35].

Stratified Analysis: If possible, analyze performance across subgroups with different prevalence rates to demonstrate how predictive values vary [28].

Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Value Studies

The following reagents and methodologies are essential for conducting robust evaluations of diagnostic test performance:

| Research Reagent/Methodology | Function in Predictive Value Studies |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard Materials | Establish definitive disease status for calculating true positives and negatives [33] [23] |

| Validated Positive Controls | Ensure test sensitivity by confirming detection of known positive samples [30] |

| Validated Negative Controls | Ensure test specificity by confirming non-reactivity with known negative samples [30] |

| Population Characterization Assays | Accurately determine prevalence in study populations through independent methods [31] [28] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Compute performance metrics with confidence intervals (e.g., R, SAS) [35] |

| Blinded Assessment Protocols | Minimize bias in test interpretation and result recording [23] |

Table 2: Essential research reagents and methodologies for evaluating predictive values in diagnostic studies.

Implications for Diagnostic Assay Development and Evaluation

Setting Appropriate Performance Requirements

When establishing sensitivity and specificity requirements for new assays, researchers must consider the intended use population's prevalence and the desired PPV and NPV [30]. For example, if a test must achieve ≥90% PPV and ≥99% NPV with an expected prevalence of 20%, the required sensitivity and specificity would be approximately 96% and 98% respectively [30]. This forward-thinking approach ensures that tests demonstrate adequate predictive performance in their target implementation settings.

Applications in Screening vs Diagnostic Contexts

The relationship between prevalence and predictive values has particular significance when considering screening versus diagnostic applications [23]. Screening tests are typically applied to populations with lower disease prevalence, which consequently produces lower PPVs even with reasonably high sensitivity and specificity [29]. This explains why positive screening tests often require confirmation with more specific diagnostic tests [23]. Researchers developing screening assays must recognize that apparently strong sensitivity and specificity may translate to clinically unacceptable PPV in low-prevalence populations.

PPV and NPV serve as crucial connectors between abstract test characteristics and practical diagnostic utility. Understanding how these predictive values fluctuate with disease prevalence is essential for designing appropriate validation studies, interpreting diagnostic test results, and establishing clinically relevant performance requirements. For researchers working with specificity and sensitivity functional assays, incorporating prevalence considerations into assay development and evaluation represents a critical step toward creating diagnostically useful tools that perform reliably in their intended settings. The mathematical relationships and experimental evidence presented provide a foundation for making informed decisions throughout the diagnostic development process.

Practical Measurement: Techniques for Quantifying Assay Performance

Establishing a Validated Panel of Positive and Negative Controls

In the rigorous field of biomolecular research and diagnostic assay development, the establishment of a validated panel of positive and negative controls is a critical foundation for ensuring data integrity, reproducibility, and translational relevance. Controls serve as the benchmark against which experimental results are calibrated, providing evidence that an immunohistochemistry (IHC) test or other functional assay is performing with its expected sensitivity and specificity as characterized during technical optimization [36]. Within the context of evaluating specificity and sensitivity in functional assays, a well-designed control panel transcends mere quality checking; it becomes an indispensable tool for differentiating true biological signals from experimental artifacts, thereby directly impacting the reliability of scientific conclusions and, in clinical contexts, patient care decisions.

The fundamental principle behind controls is relatively straightforward: positive controls confirm that the experimental setup is capable of producing a positive result under the known conditions, while negative controls verify that observed effects are due to the specific experimental variable and not nonspecific interactions or procedural errors [37]. However, the practical implementation of a comprehensive and validated panel requires careful consideration of biological context, technical parameters, and the specific assay platform employed. This guide provides a systematic approach to establishing such a panel, objectively comparing performance across common assay platforms, and detailing the experimental protocols necessary for rigorous validation.

Theoretical Foundations: Types and Purposes of Controls

A validated control panel is not monolithic; it comprises several distinct types of controls, each designed to monitor different aspects of assay performance. Understanding the classification and specific purpose of each control type is the first step in constructing a robust panel.

Positive Controls

Positive controls are samples or tissues known to express the target antigen or exhibit the phenomenon under investigation. They primarily monitor the calibration of the assay system and protocol sensitivity [36]. A comprehensive panel should include:

- External Positive Tissue Controls (Ext-PTC): Separate tissue sections or cell lines known to express the target antigen. These should ideally undergo fixation and processing identical to the test samples to ensure comparable performance [36].

- Internal Positive Tissue Controls (Int-PTC): Native, intrinsic elements within the patient's own test tissue that are known to consistently express the target antigen. The presence of expected staining in these internal controls provides strong evidence of proper assay function for that specific sample [36].

For maximum confidence, positive controls should represent a range of expression levels, including both low-expression and high-expression samples, to demonstrate that the assay sensitivity is sufficient to detect the target across its biological spectrum [38] [36].

Negative Controls

Negative controls are essential for evaluating the specificity of an IHC test and for identifying false-positive staining reactions [36]. They are categorized based on their preparation and specific application:

- Negative Reagent Controls (NRCs): These controls involve replacing the primary antibody with a non-immune immunoglobulin of the same species, isotype, and concentration. This identifies false-positive reactions due to nonspecific binding of the primary antibody or components of the detection system [36].

- Negative Tissue Controls (NTCs): These consist of tissues or cells where the target protein is known to be absent. The absence of staining in these samples confirms that the detected signal in test samples is specific to the target antigen and not due to cross-reactivity or other artifacts [38].

Table 1: Classification and Application of Key Control Types

| Control Type | Purpose | Composition | Interpretation of Valid Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Positive Control (Ext-PTC) | Monitor assay sensitivity and calibration | Tissue/cell line with known target expression, processed like test samples | Positive staining in expected distribution and intensity |

| Internal Positive Control (Int-PTC) | Monitor assay performance for a specific sample | Indigenous elements within the test tissue known to express the target | Positive staining in expected indigenous elements |

| Negative Reagent Control (NRC) | Identify false-positives from antibody/detection system | Primary antibody replaced with non-immune Ig | Absence of specific staining |

| Negative Tissue Control (NTC) | Confirm target-specific staining | Tissue/cell line known to lack the target antigen | Absence of specific staining |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for incorporating these different controls into a validated assay system, ensuring both sensitivity and specificity are monitored.

Diagram: Control Implementation Logic for Assay Validation

Establishing a Validated Control Panel: A Step-by-Step Methodology

Building a validated panel requires a strategic approach that encompasses material selection, experimental design, and data interpretation. The following protocols provide a framework for this process.

Selection and Sourcing of Control Materials

The foundation of a reliable control panel is the careful selection of its components.

- Cell Lines and Tissues: Cell lines that endogenously express or lack the protein of interest are widely used as controls [38]. For instance, in validating a CD19 antibody, the RAJI B-cell line served as a positive control, while JURKAT (T-cell) and U937 (monocytic) lines acted as negative controls [38]. The use of well-characterized tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing both positive and negative control tissues on a single slide is a powerful approach for efficient validation [38].

- Transfected Cells: For targets where naturally expressing cell lines are unavailable, transfected cells (e.g., COS-7, HEK293T) expressing the target antigen via cDNA are valuable positive controls. The negative control in this case should consist of cells transfected with the empty vector only [38]. A critical preliminary step is to verify that the host cell line does not endogenously express the target or a cross-reactive protein.

- Purified Proteins: Purified proteins or peptides are ideal positive controls in techniques like Western blot and ELISA. They can be used to verify antibody specificity and, in ELISA, to generate standard curves for quantification [37].

- Induced Systems: For inducible targets, systems that allow controlled expression, such as the tetracycline (TetON)-inducible system in transgenic mice used for Nanog validation, provide dynamic positive controls with varying expression levels [38].

Experimental Protocol for Control Panel Validation via Western Blot

Western blotting is a cornerstone technique for protein analysis, and its validation requires a multi-faceted control panel.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Test Samples: Lyse cells or tissues of interest in an appropriate RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Positive Controls: Use a cell lysate known to express the target protein (e.g., a characterized cell line or a lysate from Rockland, which offers pre-validated products) [37]. For transfected systems, use lysates from cells expressing the recombinant target.

- Negative Controls: Use a cell lysate from a source known to lack the target protein (e.g., a different cell lineage) or from empty-vector transfectants [38].

- Loading Control: Prepare samples for a constitutively expressed housekeeping protein (e.g., β-actin, GAPDH, α-tubulin) with a molecular weight distinct from the target to verify equal protein loading across all lanes [37].

2. Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer:

- Load equal amounts of protein (20-30 µg) from each sample, including positive, negative, and loading controls, onto an SDS-PAGE gel (4-20% gradient).

- Perform electrophoresis and transfer to a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane using standard protocols.

3. Immunoblotting:

- Block the membrane with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 hour.

- Incubate with the primary antibody against your target protein, diluted in blocking buffer, overnight at 4°C.

- Include a separate blot or strip for the loading control antibody.

- Wash the membrane and incubate with an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Detect the signal using a chemiluminescent substrate and image the blot.

4. Interpretation:

- A valid result shows a band at the expected molecular weight in the positive control and test samples, with no band in the negative control.

- The loading control should show uniform band intensity across all lanes, confirming equal loading.

Table 2: Example Control Panel for a CD19 Western Blot

| Sample Type | Expected Result (CD19) | Purpose | Example Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Control | Band at ~95 kDa | Confirm assay works | RAJI B-cell lysate [38] |

| Negative Control | No band | Confirm antibody specificity | JURKAT T-cell lysate [38] |

| Loading Control | Uniform band (e.g., 42 kDa for β-actin) | Verify equal protein loading | All sample lanes |

Experimental Protocol for Control Panel Validation via Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC presents unique challenges for validation, particularly concerning tissue integrity and staining interpretation.

1. Slide Preparation:

- Test Tissues: Section formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) test tissues.

- Positive Control Tissues: Use a multi-tissue block (TMA) containing cores from tissues known to express the target (e.g., lymph node for PD-1) [38]. The Ext-PTC should have undergone similar fixation and processing.

- Negative Control Tissues: Use a TMA containing cores from tissues known to lack the target (e.g., kidney, heart for PD-1) [38].

- Consecutive Sections: For NRCs, use a consecutive section from the test block itself.

2. Staining Protocol:

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate the slides.

- Perform antigen retrieval using a method optimized for the target.

- Block endogenous peroxidases and apply a protein block to reduce nonspecific binding.

- For the test slide: Apply the validated primary antibody.

- For the Negative Reagent Control (NRC) slide: Apply a non-immune immunoglobulin of the same isotype and concentration as the primary antibody [36].

- Apply the detection system (e.g., polymer-based system) and chromogen.

- Counterstain, dehydrate, and mount.

3. Interpretation:

- The test slide should show specific staining in the test tissue and the Ext-PTC.

- The NRC slide should show an absence of specific staining, confirming the primary antibody's specificity.

- The Int-PTC, if present, should show appropriate staining.

- Staining patterns should be compared with another antibody against the same target, if available, to strengthen confidence [38].

Comparative Performance Across Assay Platforms

The performance and requirements for control panels can vary significantly across different analytical platforms. The following comparison highlights how control strategies are applied in two common but distinct techniques: the traditional ELISA and the more modern Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR).

ELISA vs. SPR: A Control Perspective

ELISAs are standard plate-based assays relying on enzyme-linked antibodies for detection, while SPR is a label-free, real-time method that measures binding via changes in refractive index [39].

Table 3: Platform Comparison for Biomolecular Detection and Control Application

| Parameter | ELISA | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Measurement | End-point, quantitative (affinity only) | Real-time, quantitative (affinity & kinetics) [39] |

| Label Requirement | Yes (enzyme-conjugated antibody) | No (label-free) [39] |

| Assay Time | Long (>1 day), multiple steps | Short (minutes to hours), streamlined [39] |

| Low-Affinity Interaction Detection | Poor (washed away in steps) | Excellent (real-time monitoring) [39] |

| Positive Control Role | Verify enzyme and detection chemistry | Verify ligand immobilization and system response |

| Negative Control Role | Identify cross-reactivity of antibodies | Identify nonspecific binding to sensor chip |

| Typical Positive Control | Sample with known target concentration | Purified analyte with known kinetics |

| Typical Negative Control | Sample without target / Isotype control | A non-interacting analyte / blank flow cell |

The workflow for these two techniques, from setup to data analysis, differs substantially, as outlined below.

Diagram: Comparative Workflows of ELISA and SPR Assays

Supporting Data from Comparative Studies

Empirical evidence underscores the importance of platform selection and rigorous control. A 2024 study comparing an in-house ELISA with six commercial ELISA kits for detecting anti-Bordetella pertussis antibodies revealed significant variability. The detection of IgA and IgG antibodies at a significant level ranged from 5.0% to 27.0% and 12.0% to 70.0% of patient sera, respectively, across different kits. Furthermore, the results from the commercial kits were consistent for IgG in only 17.5% of cases, highlighting that even with controlled formats, performance can differ dramatically [40]. This variability reinforces the necessity for labs to establish and validate their own control panels tailored to their specific protocols.

Conversely, studies comparing ELISA with SPR demonstrate SPR's superior ability to detect low-affinity interactions. In one investigation, SPR detected a 4% positivity rate for low-affinity anti-drug antibodies (ADAs), compared to only 0.3% by ELISA, showcasing SPR's higher sensitivity for these clinically relevant molecules [39]. This has direct implications for control panel design; validating an assay for low-affinity binders requires controls that can challenge the system's lower detection limits, for which SPR is inherently more suited.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A properly equipped laboratory is fundamental to establishing and maintaining a validated control panel. The following table details key reagents and their functions in this process.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Control Panel Establishment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Control Panels | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Cell Lines | Serve as reproducible sources of positive and negative control material. | RAJI (CD19+), JURKAT (CD19-) for flow cytometry [38]. |

| Control Cell Lysates & Nuclear Extracts | Ready-to-use positive controls for Western blot, ensuring lot-to-lot reproducibility. | Rockland's whole-cell lysates or nuclear extracts from specific cell lines or tissues [37]. |

| Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) | Allow simultaneous testing on multiple validated tissues on a single slide for IHC. | TMAs containing lymph node, spleen (positive) and kidney, heart (negative) for PD-1 [38]. |

| Purified Proteins/Peptides | Act as positive controls and standards for quantification in ELISA and Western blot. | Used to verify antibody specificity in a competition assay or generate a standard curve [37]. |

| Loading Control Antibodies | Detect housekeeping proteins to verify equal sample loading in Western blot. | Antibodies against β-actin, GAPDH, or α-tubulin [37]. |

| Isotype Controls | Serve as critical negative reagent controls (NRCs) for techniques like flow cytometry and IHC. | Non-immune mouse IgG2a used when testing with a mouse IgG2a monoclonal antibody [36]. |

| Low Endotoxin Control IgGs | Act as critical controls in sensitive biological assays like neutralization experiments. | Low endotoxin mouse or rabbit IgG to rule out endotoxin effects in cell-based assays [37]. |