From Gene to Trait: Decoding the Genotype-Phenotype Relationship for Precision Medicine and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex relationship between genotype and phenotype, a cornerstone concept in genetics with profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

From Gene to Trait: Decoding the Genotype-Phenotype Relationship for Precision Medicine and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex relationship between genotype and phenotype, a cornerstone concept in genetics with profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational principles, from the historical distinction made by Wilhelm Johannsen to the modern understanding of how genetic makeup, environmental factors, and epigenetic modifications interact to produce observable traits. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological applications, including the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning for phenotype prediction. It critically examines challenges in the field, such as data heterogeneity and model interpretability, and offers a comparative evaluation of computational and experimental validation strategies. The synthesis of these elements provides a roadmap for leveraging genetic insights to advance precision medicine, improve diagnostic accuracy, and accelerate targeted drug discovery.

The Biological Blueprint: Foundational Concepts and Complexity in Genotype-Phenotype Dynamics

The genotype–phenotype distinction represents one of the conceptual pillars of twentieth-century genetics and remains a fundamental framework in modern biological research [1]. First proposed by the Danish scientist Wilhelm Johannsen in 1909 and further developed in his 1911 seminal work, "The Genotype Conception of Heredity," this distinction provided a revolutionary departure from prior conceptualizations of heredity [1] [2] [3]. Johannsen's terminology offered a new lexicon for genetics, introducing not only the genotype-phenotype dichotomy but also the term "gene" as a unit of heredity free from speculative material connotations [4] [3]. This conceptual framework emerged from Johannsen's meticulous plant breeding experiments and was instrumental in refuting the "transmission conception" of heredity, which presumed that parental traits were directly transmitted to offspring [1] [2]. Within the context of contemporary research on genotype-phenotype relationships, understanding this historical foundation is crucial for appreciating how genetic variability propagates across biological levels to influence disease manifestation, therapeutic responses, and complex traits—a central challenge in precision medicine and functional genomics.

Historical Context and Intellectual Genesis

The Scientific Landscape circa 1900

Johannsen's work emerged during a period of intense debate within evolutionary biology regarding the mechanisms of heredity and variation [1] [3]. The scientific community was divided between Biometricians, who followed Darwin in emphasizing continuous variation and the efficacy of natural selection, and Mendelians, who argued for discontinuous evolution through mutational leaps [1] [3]. This controversy was exacerbated by the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's work in 1900 [3]. Competing theories included:

- Darwin's theory of pangenesis, which proposed that characteristics acquired during an organism's lifetime could be inherited [1] [5].

- August Weismann's germ-plasm theory, which postulated a strict separation between germ cells and somatic cells [1] [5].

- Galton's law of ancestral heredity, which stated that offspring tend to exhibit the average of their racial type rather than parental characteristics [3].

Johannsen's genius lay in his ability to transcend these debates through carefully designed experiments that differentiated between hereditary and non-hereditary variation.

Johannsen's Pure Line Experiments

Johannsen's conceptual breakthrough stemmed from his pure-line breeding experiments conducted on self-fertilizing plants, particularly the princess bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) [1] [4] [3]. His experimental protocol can be summarized as follows:

Table: Johannsen's Pure Line Experimental Protocol

| Experimental Phase | Methodology | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Population Selection | Selected 5,000 beans from a genetically heterogeneous population; measured and recorded individual seed weights [3]. | Found continuous variation in seed weight across the population [3]. |

| Line Establishment | Created pure lines through repeated self-fertilization of individual plants, ensuring each line was genetically homozygous [1] [4]. | Established that each pure line had a characteristic average seed weight [1]. |

| Selection Application | Within each pure line, selected and planted the heaviest and lightest seeds over multiple generations [1] [3]. | Demonstrated that selection within pure lines produced no hereditary change in seed weight; offspring regressed to the line's characteristic mean [1] [3]. |

| Statistical Analysis | Employed statistical methods to compare weight distributions between generations and across different pure lines [1]. | Distinguished between non-heritable "fluctuations" (within lines) and heritable differences (between lines) [1] [5]. |

Conceptual Formalization

From these experiments, Johannsen formalized his core concepts in his 1909 textbook Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre (The Elements of an Exact Theory of Heredity) [1] [3]:

- Phenotype: "All 'types' of organisms, distinguishable by direct inspection or only by finer methods of measuring or description" [5]. The phenotype represents the observable characteristics of an organism resulting from the interaction between its genotype and environmental factors during development [1] [2].

- Genotype: "The sum total of all the 'genes' in a gamete or in a zygote" [5]. The genotype constitutes the hereditary constitution of an organism, which Johannsen considered particularly stable and immune to environmental influences [1].

- Gene: A term Johannsen coined from de Vries' "pangene," defining it as a unit free from any hypothesis about its material nature, representing only the "securely ascertained fact" that many organismal properties are conditioned by separable factors in the gametes [4].

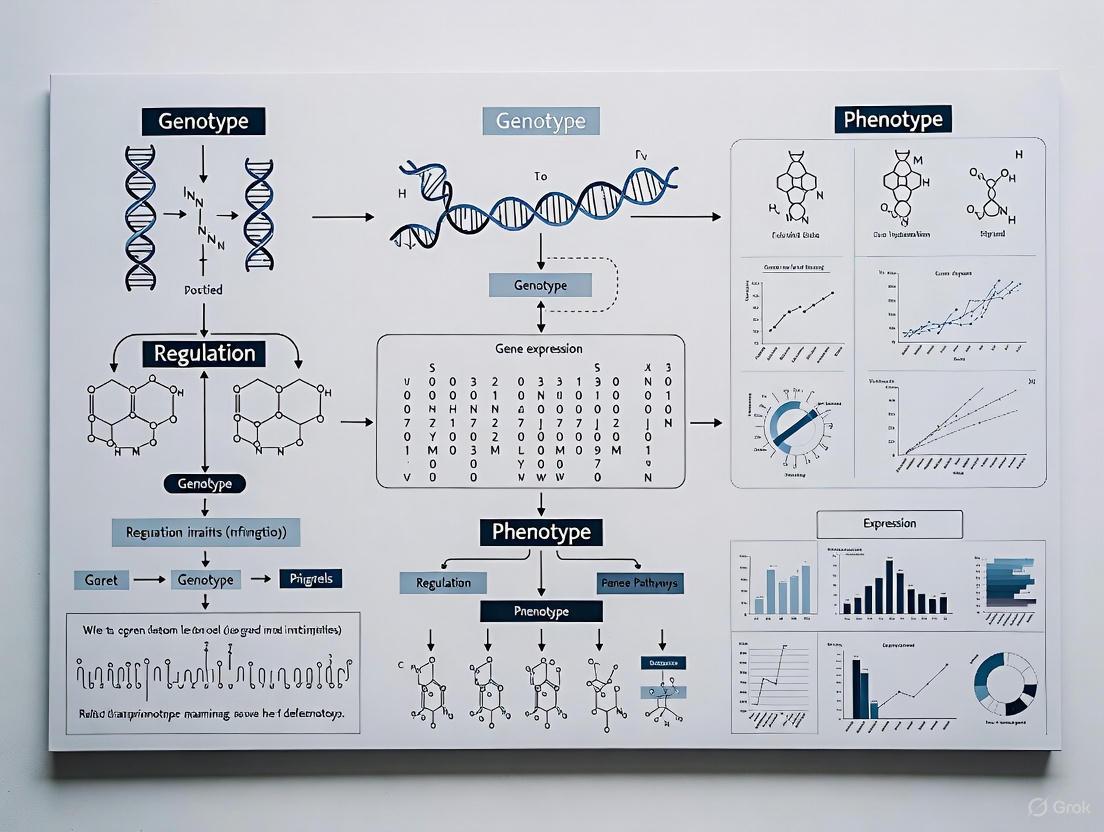

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and logical relationships of Johannsen's pure line experiment and the conceptual distinctions it revealed:

The Original Meaning and Its Evolution

Johannsen's Holistic Interpretation

Contrary to modern genocentric views, Johannsen maintained a holistic interpretation of the genotype [4]. He viewed the genotype not merely as a collection of discrete genes but as an integrated complex system. In his conception:

- The genotype represented the entire developmental potential of an organism [4].

- Genes were abstractly defined as "calculation units" or accounting devices to explain hereditary patterns, without commitment to their physical nature [4] [3].

- He explicitly rejected what he called the "transmission conception" of heredity, which assumed that parental traits were directly transmitted to offspring [1] [2].

- He equated the genotype with Richard Woltereck's concept of Reaktionsnorm (norm of reaction), emphasizing the range of potential phenotypic expressions across different environments [1].

This holistic view contrasted sharply with the increasingly reductionist direction that genetics would take in subsequent decades, particularly with the rise of the chromosome theory [4].

Contrast with Modern Meanings

Table: Evolution of Genotype-Phenotype Terminology

| Concept | Johannsen's Original Meaning (1909-1911) | Predominant Modern Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | The class identity of a group of organisms sharing the same hereditary constitution; a holistic concept [2] [4]. | The specific DNA sequence inherited from parents [2]. |

| Phenotype | The variable appearances of individuals within a genotype, influenced by environment [2] [3]. | The observable physical and behavioral traits of an organism [2]. |

| Gene | A unit of calculation for hereditary patterns; explicitly non-hypothetical about material basis [4] [3]. | A specific DNA sequence encoding functional product [4]. |

| Primary Application | Describing differences between pure lines or populations [2]. | Describing individuals and their specific genetic makeup [2]. |

Philosophical and Scientific Implications

Johannsen's distinction carried profound implications for biological thought:

- It established an "ahistorical" conception of heredity, wherein the genotype passed unchanged from generation to generation, immune to environmental influences experienced by the organism during its lifetime [1].

- It created a conceptual framework that explicitly separated the study of heredity from the study of development [1]. Developmental biology became the study of how genotypes give rise to phenotypes, contrary to embryologists who viewed heredity and development as inseparable processes [1].

- It provided a resolution to the debate between Biometricians and Mendelians by demonstrating that continuous variation could contain both heritable and non-heritable components [1] [5].

- It limited the power of natural selection to "sort out pre-existing genotypes within heterogeneous natural populations" rather than creating new variation [1].

Modern Research Applications and Methodologies

Contemporary Genotype-Phenotype Correlation Studies

Modern research has dramatically expanded the scope and methodology of genotype-phenotype mapping, particularly in medical genetics. Current approaches include:

4.1.1 Cross-Sectional Studies of Genetic Syndromes Recent investigations into Noonan syndrome (NS) and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (NSML) demonstrate sophisticated genotype-phenotype correlation methods [6]. These studies:

- Recruit individuals with specific genetic variants (e.g., in PTPN11, SOS1, RAF1 genes)

- Use standardized behavioral questionnaires (e.g., SRS-2 for social responsiveness, CBCL for emotional problems)

- Correlise specific mutations with biochemical profiling (e.g., SHP2 enzyme activity assays)

- Employ logistic regression to quantify how specific genetic functional changes (e.g., fold activation of SHP2) increase the likelihood of particular phenotypic traits (e.g., restricted and repetitive behaviors) [6]

4.1.2 Large-Scale Database Integration The development of specialized databases addresses the challenge of interpreting numerous genetic variants:

- NMPhenogen: A comprehensive database for neuromuscular genetic disorders (NMGDs) correlating genotypes from 747 nuclear and mitochondrial genes with detailed phenotypic information [7].

- Utilizes the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines for standardized variant classification [7].

- Integrates population data, computational predictions, and functional assays to establish clinically relevant correlations [7].

4.1.3 Functional Genomics and Spatial Transcriptomics Cutting-edge approaches now enable high-resolution mapping:

- PERTURB-CAST: A method integrating combinatorial genetic perturbations with spatial transcriptomics to decode genotype-phenotype relationships in tumor ecosystems [8].

- CHOCOLAT-G2P: A scalable framework for studying higher-order combinatorial perturbations that mimic tumor heterogeneity [8].

- These technologies allow researchers to investigate how complex genetic alterations manifest in tissue-level phenotypes while preserving spatial context [8].

The Multi-Level Phenotype Concept

The modern conception of phenotype has expanded dramatically beyond Johannsen's original definition. Today, phenotypes are investigated at multiple biological levels:

This expansion means that important genetic and evolutionary features can differ significantly depending on the phenotypic level considered, with variation at one level not necessarily propagating predictably to other levels [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Genotype-Phenotype Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Field Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Lines | Genetically homogeneous populations for distinguishing hereditary vs. environmental variation [1]. | Johannsen's bean lines; inbred model organisms [1] [4]. |

| Standardized Behavioral Assessments | Quantitatively measure behavioral phenotypes for correlation with genetic variants [6]. | SRS-2 for autism-related traits; CBCL for emotional problems [6]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | Map gene expression patterns within tissue architecture to understand phenotypic consequences [8]. | 10X Visium used in PERTURB-CAST for tumor ecosystem analysis [8]. |

| Functional Assay Reagents | Measure biochemical consequences of genetic variants in experimental systems [6]. | SHP2 activity assays for PTPN11 variants in Noonan syndrome [6]. |

| Curated Variant Databases | Classify and interpret pathogenicity of genetic variants using standardized criteria [7]. | ACMG guidelines implementation in NMPhenogen for neuromuscular disorders [7]. |

| Combinatorial Perturbation Systems | Study complex genetic interactions that mimic disease heterogeneity [8]. | CHOCOLAT-G2P framework for investigating higher-order combinatorial mutations [8]. |

Wilhelm Johannsen's genotype-phenotype distinction established a conceptual foundation that continues to shape biological research more than a century after its introduction. While the predominant meanings of these terms have evolved—particularly with the molecular biological revolution that identified DNA as the material basis of heredity—the essential framework remains remarkably prescient [2]. Johannsen's insight that the genotype represents potentialities whose expression depends on developmental processes and environmental contexts anticipated modern concepts of phenotypic plasticity, genetic canalization, and norm of reaction [1] [9].

In contemporary research, particularly in the age of precision medicine and functional genomics, the relationship between genotype and phenotype remains a central research program. The challenge has expanded from Johannsen's statistical analysis of seed weight variations to understanding how genetic variation propagates across multiple phenotypic levels—from molecular and cellular traits to organismal and clinical manifestations—to ultimately shape fitness and disease susceptibility [5]. Johannsen's holistic perspective on the genotype as an integrated system rather than a mere collection of discrete genes has regained relevance as researchers grapple with polygenic inheritance, epistasis, and the complexities of gene regulatory networks [4].

The enduring utility of Johannsen's conceptual framework lies in its ability to accommodate increasingly sophisticated methodologies while maintaining the essential distinction between hereditary potential and manifested characteristics. As modern biology develops increasingly powerful tools for probing the genotype-phenotype relationship—from single-cell omics to spatial transcriptomics and genome editing—the foundational concepts articulated by Johannsen continue to provide the "conceptual pillars" upon which our understanding of heredity and biological variation rests [1].

The relationship between genotype and phenotype represents one of the most fundamental concepts in biology. Traditionally viewed through a lens of direct causality, this paradigm has undergone substantial revision with increasing appreciation for the complex interplay between genetic information and environmental influences. Phenotypic plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce multiple phenotypes in response to environmental conditions—has emerged as a critical mechanism enabling organisms to cope with environmental variation [10] [11]. This capacity for responsive adaptation operates across all domains of life, from the decision between lytic and lysogenic cycles in bacteriophages to seasonal polyphenisms in butterflies and acclimation responses in plants [11] [12].

Contemporary research frameworks now recognize that the developmental trajectory from genetic blueprint to functional organism involves sophisticated regulatory processes that integrate environmental signals. As West-Eberhard articulated, the origin of novelty often begins with environmentally responsive, developmentally plastic organisms [11]. This perspective does not diminish the importance of genetic factors but rather emphasizes how environmental influences act through epigenetic mechanisms to shape phenotypic outcomes, creating a more dynamic and responsive relationship between genes and traits. Understanding these mechanisms is particularly relevant for drug development professionals seeking to comprehend individual variation in treatment response and for researchers investigating complex disease etiologies that cannot be explained by genetic variation alone [13].

Biological Mechanisms: Epigenetic Pathways and Environmental Sensing

Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Regulation

Epigenetic regulation comprises molecular processes that modulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These mechanisms provide the molecular infrastructure for phenotypic plasticity by translating environmental experiences into stable cellular phenotypes [13]. The major epigenetic pathways include:

- DNA methylation: The addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases, primarily at CpG dinucleotides, typically associated with transcriptional repression when occurring in promoter regions. This modification represents a high-energy carbon-carbon bond that can be stable through cell divisions [13] [14].

- Histone modifications: Post-translational alterations to histone proteins including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and ADP-ribosylation. These modifications influence chromatin structure and DNA accessibility [13]. For example, acetylation of lysine residues on histone H3 (K14, K9) is generally associated with active transcription, while methylation of H3-K9 is linked to transcriptional silencing [13].

- Non-coding RNAs: RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, including microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [13] [15].

These mechanisms function interdependently; for instance, methyl-CpG binding proteins (MeCP2) can recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs) to establish repressive chromatin states, demonstrating how DNA methylation and histone modifications act synergistically [13].

Environmental Sensing and Response

Epigenetic mechanisms serve as molecular interpreters that translate environmental signals into coordinated gene expression responses. This environmental sensing capacity enables phenotypic adjustments across diverse timescales, from rapid physiological responses to transgenerational adaptations [10] [16]. Examples include:

- Nutritional sensing: Dietary composition influences digestive enzyme plasticity through epigenetic mechanisms, as demonstrated in house sparrows that show increased maltase activity when transitioning from insect-based to seed-based diets [12].

- Thermal acclimation: Ectothermic organisms adjust membrane lipid composition through epigenetic regulation to maintain fluidity across temperature ranges [12].

- Stress responses: Maternal care behaviors in rats program offspring stress responses through epigenetic modification of glucocorticoid receptor genes, particularly in the hippocampal region [14].

The reliability of environmental cues significantly determines whether plastic responses prove adaptive. When environmental signals become unreliable due to anthropogenic change, formerly adaptive plasticity can become maladaptive, creating ecological traps [10].

Empirical Evidence: From Model Systems to Human Health

Plant and Animal Model Systems

Research in model systems has been instrumental in elucidating the mechanisms and evolutionary consequences of phenotypic plasticity:

Table 1: Empirical Evidence of Phenotypic Plasticity Across Taxa

| Organism | Plastic Trait | Environmental Cue | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ludwigia arcuata (aquatic plant) | Leaf morphology (aerial vs. submerged) | Air/water contact | ABA and ethylene hormone signaling | [12] |

| Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid) | Reproductive mode (asexual/sexual), wing development | Population density | Unknown developmental switch | [12] |

| Pristimantis mutabilis (mutable rain frog) | Skin texture | Unknown | Rapid morphological change | [12] |

| Theodoxus fluviatilis (snail) | Osmolyte concentration | Water salinity | Stress-induced epigenetic modifications | [16] |

| Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) | Metabolic traits (triglyceride levels) | Parental environment | Parent-of-origin effects | [10] |

| House sparrows | Digestive enzyme activity | Dietary composition (insect vs. seed) | Modulation of maltase and aminopeptidase-N | [12] |

These examples demonstrate the taxonomic breadth of phenotypic plasticity and highlight how different organisms have evolved specialized mechanisms to respond to environmental challenges.

Human Health and Disease Implications

In humans, epigenetic mechanisms mediate gene-environment interactions that influence disease susceptibility and developmental outcomes [13] [17]. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis posits that early-life environmental exposures program long-term health trajectories through epigenetic mechanisms [17]. Key evidence includes:

- Maternal care effects: In rodent models, variations in maternal licking and grooming behavior produce stable epigenetic modifications in offspring, affecting glucocorticoid receptor expression and stress responsiveness throughout life [14].

- Metabolic disease: Both maternal undernutrition and overnutrition during critical developmental windows can produce epigenetic changes that increase susceptibility to obesity and type 2 diabetes in adulthood [13].

- Mental health: Early-life adversity associates with persistent epigenetic changes in genes regulating stress response, neurotransmitter function, and neural plasticity, potentially mediating risk for psychiatric disorders [14].

These findings have profound implications for preventive medicine and therapeutic development, suggesting that epigenetic biomarkers could identify individuals at elevated risk for certain conditions and that interventions targeting epigenetic mechanisms might reverse or mitigate the effects of adverse early experiences.

Methodologies: Investigating Plasticity and Epigenetic Regulation

Experimental Approaches and Workflows

Research in phenotypic plasticity and epigenetics employs specialized methodologies to disentangle genetic, environmental, and epigenetic contributions to phenotypic variation:

Table 2: Key Methodological Approaches in Plasticity Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Profiling | Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), MeDIP-Seq | Genome-wide DNA methylation mapping | Bisulfite conversion efficiency; cell type heterogeneity impacts data quality [15] |

| Chromatin Analysis | ChIP-Seq, ATAC-Seq, Hi-C | Histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, 3D genome architecture | Antibody specificity; cross-linking artifacts |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-Seq, Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Gene expression responses to environmental variation | Batch effects; normalization methods |

| Population Genomics | GWAS, pangenome graphs, structural variant analysis [18] | Identifying genetic loci underlying plastic responses | Sample size requirements; variant annotation |

| Experimental Designs | Common garden, reciprocal transplant, cross-fostering | Disentangling genetic and environmental effects | Logistic constraints; timescales needed |

Recent methodological advances include telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies that enable comprehensive characterization of structural variants, which have been shown to contribute substantially to phenotypic variation—accounting for an additional 14.3% heritability on average compared to SNP-only analyses in yeast models [18]. Population epigenetic approaches that apply population genetic theory to epigenetic variation are also emerging as powerful tools to understand the evolutionary dynamics of epigenetic variation [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plasticity and Epigenetics Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, zebularine | DNA methyltransferase inhibition; experimental epigenome manipulation | Cytotoxic effects; incomplete specificity |

| Histone Modifiers | Trichostatin A (HDAC inhibitor), JQ1 (BET bromodomain inhibitor) | Altering histone acetylation patterns; probing chromatin function | Pleiotropic effects; dosage optimization |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits, MethylCode kits | DNA treatment for methylation detection | Incomplete conversion; DNA degradation |

| Antibodies for Chromatin Studies | Anti-5-methylcytosine, anti-H3K27ac, anti-H3K4me3 | Chromatin immunoprecipitation; epigenetic mark detection | Specificity validation; lot-to-lot variability |

| Environmental Chambers | Precision growth chambers, aquatic systems | Controlled environmental manipulation | Parameter stability; microenvironment variation |

| Epigenetic Editing Tools | CRISPR-dCas9 fused to DNMT3A/TET1, KRAB repressors | Locus-specific epigenetic manipulation | Off-target effects; persistence of modifications |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Evidence and Heritability

Quantitative Patterns in Phenotypic Plasticity Research

Rigorous quantitative analysis is essential for interpreting plasticity research. Key datasets include:

Table 4: Quantitative Evidence for Epigenetic and Plasticity Phenomena

| Phenomenon | System | Effect Size | Statistical Evidence | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Variant Impact | S. cerevisiae (1,086 isolates) | 14.3% average increase in heritability with SV inclusion | SVs more frequently associated with traits than SNPs | [18] |

| Transgenerational Plasticity | Stickleback fish | Context-dependent: beneficial only when offspring environment matched parental | Significant G×E interaction (p<0.05) | [10] |

| DNA Methylation Stability | Natural populations | Varies by taxa: higher in plants/fungi than animals | Measures of epimutation rates | [15] |

| Maternal Care Effects | Rat model | 2-fold difference in glucocorticoid receptor mRNA | p<0.001 between high vs low LG offspring | [14] |

| Digestive Plasticity | House sparrow | 2-fold increase in maltase activity with diet change | Significant diet effect (p<0.01) | [12] |

These quantitative findings demonstrate the substantial contributions of epigenetic mechanisms and plasticity to phenotypic diversity. The large-scale yeast genomic study highlights how previously underexplored genetic elements, particularly structural variants, contribute significantly to trait variation [18]. Meanwhile, the context-dependency of transgenerational effects emphasizes that the adaptive value of plasticity depends on environmental predictability [10].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, the field faces several methodological and conceptual challenges that require innovative solutions:

Methodological Limitations

Current limitations in plasticity and epigenetics research include:

- Cell type heterogeneity: Epigenetic patterns are highly cell-type-specific, and studies using heterogeneous tissues (e.g., whole blood) may confound true signals with changes in cell population composition [15]. Only 44% of studies in a recent review adequately controlled for this factor [15].

- Technical variability: Bisulfite conversion methods vary in efficiency and can introduce biases, while antibody-based approaches face specificity challenges [15]. Technical replication is rarely implemented (only 12% of studies) due to cost-benefit tradeoffs [15].

- Sample size constraints: The average sample size in epigenetic studies is approximately 18 per group, substantially underpowered for detecting small-effect loci given the multiple testing burden in genome-wide analyses [15].

- Transgenerational evidence: Only 11% of studies assess epigenetic stability beyond the F3 generation, which is essential for establishing evolutionary relevance [15].

Conceptual Framework Advances

Future research directions will need to address several conceptual gaps:

- Distinguishing adaptation from fortuity: A critical challenge lies in determining whether observed plasticity represents an adaptation shaped by natural selection or merely a fortuitous response to environmental conditions [10] [11].

- Plasticity's evolutionary role: Debate continues regarding whether plasticity generally promotes or hinders genetic adaptation, with evidence supporting both facilitation (by buying time for genetic adaptation) and hindrance (by shielding genetic variation from selection) [10].

- Timescale integration: Different plastic responses operate across vastly different timescales, from rapid behavioral adjustments to transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, requiring theoretical frameworks that integrate these diverse temporal dimensions [10].

Future research should prioritize multi-generational studies with adequate sample sizes, controlled cell type composition, and integrated genomic-epigenomic analyses to fully resolve the role of plasticity in evolution and disease.

The relationship between genotype and phenotype is fundamentally shaped by two pervasive biological phenomena: genetic heterogeneity, where different genetic variants lead to the same clinical outcome, and pleiotropy, where a single genetic variant influences multiple, seemingly unrelated traits. Advances in genomic technologies and analytical frameworks are rapidly elucidating the complex mechanisms underlying these phenomena. This whitepaper explores the latest methodological breakthroughs for dissecting heterogeneity and pleiotropy, including structural causal models, techniques for disentangling pleiotropy types, and single-cell resolution approaches. The insights gained are critical for refining disease nosology, identifying therapeutic targets, and informing drug development strategies for complex human diseases.

The initial promise of the genome era was that complex diseases and traits would be mapped to a manageable set of genetic variants. Instead, research has revealed a landscape of overwhelming complexity, dominated by genetic heterogeneity and pleiotropy. Genetic heterogeneity manifests when the same phenotype arises from distinct genetic mechanisms across different individuals or populations. Conversely, pleiotropy occurs when a single genetic locus influences multiple, often disparate, phenotypic outcomes [19] [20].

These phenomena are not merely statistical curiosities; they represent fundamental challenges and opportunities for genomic medicine. For drug development, a variant with pleiotropic effects might simultaneously influence a target disease and unintended side effects. Understanding heterogeneity is equally crucial, as a treatment effective for a genetically defined patient subgroup may fail in a broader population with phenotypically similar but genetically distinct disease. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide a technical guide for navigating this complexity, offering robust analytical frameworks and experimental protocols to advance genotype-phenotype research.

Methodological Frameworks for Dissecting Genetic Architecture

The Causal Pivot Model for Addressing Heterogeneity

A primary challenge in analyzing genetically heterogeneous diseases is that standard association tests can fail to detect causal variants when their effects are masked by other, stronger risk factors. The Causal Pivot (CP) is a structural causal model (SCM) designed to overcome this by leveraging established causal factors to detect the contribution of additional candidate causes [21] [22].

The model typically uses a polygenic risk score (PRS) as a known cause and evaluates rare variants (RVs) or RV ensembles as candidate causes. A key innovation is its handling of outcome-induced association by conditioning on disease status. The method derives a conditional maximum-likelihood procedure for binary and quantitative traits and develops the Causal Pivot likelihood ratio test (CP-LRT) to detect causal signals [22].

Table 1: Key Applications of the Causal Pivot Model

| Disease Analyzed | Known Cause (PRS) | Candidate Cause (Rare Variants) | CP-LRT Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypercholesterolemia (HC) | UK Biobank-derived PRS | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in LDLR | Significant signal detected |

| Breast Cancer (BC) | UK Biobank-derived PRS | Loss-of-function mutations in BRCA1 | Significant signal detected |

| Parkinson Disease (PD) | UK Biobank-derived PRS | Pathogenic variants in GBA1 | Significant signal detected |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Causal Pivot Likelihood Ratio Test

The following workflow provides a detailed protocol for applying the CP-LRT, as implemented in UK Biobank analyses [21] [22]:

- Phenotype Definition: Define case-control status or quantitative trait values using precise criteria (e.g., ICD-10 codes for diseases, lab values like LDL cholesterol ≥4.9 mmol/L for hypercholesterolemia).

- Genetic Data Processing:

- PRS Calculation: Compute polygenic risk scores for all individuals using effect sizes from large, independent GWAS summary statistics.

- Rare Variant Calling: Identify rare variants (e.g., from whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing data). Focus on functionally consequential variants, such as ClinVar-classified pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants or loss-of-function mutations in disease-relevant genes.

- Ancestry Adjustment: Account for population stratification using methods like genetic matching, inverse probability weighting, regression adjustment, or doubly robust methods.

- Model Fitting and Testing:

- Fit the conditional maximum-likelihood model, conditioning on disease status and including the PRS as a covariate.

- Test the null hypothesis that the candidate rare variant (or variant ensemble) has no effect on the disease trait using the CP-LRT.

- Perform control analyses, such as testing the candidate variant in cross-disease analyses or using synonymous variants, to confirm specificity.

Diagram 1: Causal Pivot Analysis Workflow.

Disentangling Horizontal and Vertical Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy is not a monolithic concept. The Horizontal and Vertical Pleiotropy (HVP) model is a novel statistical framework designed to disentangle these two distinct forms, which is critical for understanding biological mechanisms and planning interventions [23] [24].

- Horizontal Pleiotropy: A genetic variant independently influences two or more traits via distinct biological pathways. This reflects shared genetic etiology.

- Vertical Pleiotropy (Mediated Pleiotropy): A genetic variant influences one trait, which in turn causally affects a second trait. The genetic association with the second trait is indirect.

The HVP model is a bivariate linear mixed model that simultaneously considers both pathways. It can be represented as [24]: [ \begin{cases} \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{c}\tau + \boldsymbol{\alpha} + \mathbf{e} \ \mathbf{c} = \boldsymbol{\beta} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \end{cases} ] Here, (\mathbf{y}) and (\mathbf{c}) are the two traits, (\tau) is the fixed causal effect of trait (\mathbf{c}) on trait (\mathbf{y}), and (\boldsymbol{\alpha}) and (\boldsymbol{\beta}) are the random genetic effects for each trait. The model uses a combination of GREML (Genomic-Relatedness-Based Restricted Maximum Likelihood) and Mendelian randomization (MR) approaches to obtain unbiased estimates of the causal effect (\tau) and the genetic correlation due to horizontal pleiotropy [24].

Table 2: Distinguishing Horizontal and Vertical Pleiotropy with the HVP Model

| Trait Pair | Primary Driver of Genetic Correlation | Biological and Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) & Type 2 Diabetes | Horizontal Pleiotropy | Suggests shared genetic biology; CRP is a useful biomarker but not a causal target. |

| Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) & Sleep Apnea | Horizontal Pleiotropy | Suggests shared genetic biology. |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) & Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) | Vertical Pleiotropy | Lowering BMI is likely to directly reduce MetS risk. |

| Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) & Cardiovascular Disease | Vertical Pleiotropy | MetS is a causal mediator; interventions on MetS components may reduce CVD risk. |

Advanced Multi-Trait and Multi-Locus Association Methods

Beyond pairwise pleiotropy, new methods are emerging to detect genetic variants influencing a multitude of traits. The Multivariate Response Best-Subset Selection (MRBSS) method is designed for this purpose, treating high-dimensional genotypic data as response variables and multiple phenotypic data as predictor variables [25].

The core model is: [ \mathbf{Y\Delta} = \mathbf{X\Theta} + \mathbf{\varepsilon\Delta} ] where (\mathbf{Y}) is the genotype matrix, (\mathbf{X}) is the phenotype matrix, (\mathbf{\Delta}) is a diagonal matrix whose elements indicate whether a SNP is active (associated with at least one phenotype), and (\mathbf{\Theta}) is the regression coefficient matrix. The method converts the variable selection problem into a 0-1 integer optimization, efficiently identifying the subset of "active" SNPs from a large candidate set [25].

Cutting-Edge Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Single-Cell Resolution of Context-Specific Genetic Effects

Bulk RNA sequencing masks cellular heterogeneity, limiting the detection of context-specific genetic regulation. Response expression quantitative trait locus (reQTL) mapping at single-cell resolution overcomes this by modeling the per-cell perturbation state, dramatically enhancing the detection of genetic variants whose effect on gene expression changes under stimulation [26].

A key innovation is the use of a continuous perturbation score, derived via penalized logistic regression, which quantifies each cell's degree of response to an experimental perturbation (e.g., viral infection). This continuous score is used in a Poisson mixed-effects model (PME) to test for interactions between genotype and perturbation state [26].

Table 3: Single-Cell reQTL Mapping Power and Findings

| Perturbation | reQTLs Detected (2df-model) | Percentage Increase Over Discrete Model | Example of a Discovered reQTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A Virus (IAV) | 166 | ~37% | PXK (Decreased eQTL effect post-perturbation) |

| Candida albicans (CA) | 770 | ~37% | RPS26 (Stronger effect in B cells) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) | 594 | ~37% | SAR1A (rs15801 in CD8+ T cells after CA perturbation) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) | 646 | ~37% | MX1 (rs461981 in CD4+ T cells after IAV perturbation) |

Experimental Protocol: Mapping reQTLs with a Continuous Perturbation Score

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying context-dependent genetic regulators using single-cell RNA sequencing data from perturbation experiments [26]:

- Perturbation Experiment and scRNA-seq: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from dozens to hundreds of donors. Split cells from each donor, exposing one pool to a perturbation (e.g., IAV, CA, PA, MTB) and keeping another pool as an unstimulated control. Perform single-cell RNA sequencing on all cells.

- Data Pre-processing: Perform standard scRNA-seq quality control, normalization, and batch effect correction. Calculate corrected expression principal components (hPCs).

- Calculate Continuous Perturbation Score:

- Use a penalized logistic regression model with the hPCs as independent variables to predict the log odds of a cell belonging to the perturbed pool.

- The resulting score for each cell serves as a surrogate for its degree of response to the perturbation.

- Map Response eQTLs:

- Select a set of a priori eQTLs for testing.

- Fit a Poisson mixed-effects model where single-cell gene expression is a function of:

- Genotype (G)

- Interaction between genotype and discrete perturbation state (GxDiscrete)

- Interaction between genotype and the continuous perturbation score (GxScore)

- Include technical and biological covariates (e.g., sequencing depth, donor, cell cycle score).

- Statistical Testing: Use a 2-degree-of-freedom likelihood ratio test (LRT) to assess the joint significance of the GxDiscrete and GxScore interaction terms against a null model with no interactions. Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction.

Diagram 2: Single-Cell reQTL Mapping Pipeline.

Table 4: Key Reagents and Resources for Genetic Heterogeneity and Pleiotropy Studies

| Resource / Reagent | Function and Utility | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank (UKB) | A large-scale biomedical database containing deep genetic, phenotypic, and health record data from ~500,000 participants. | Discovery and validation cohort for applying CP-LRT and HVP models to human diseases [21] [27] [23]. |

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Provide extensive, longitudinal phenotype data for large patient cohorts, often linked to biobanks. | Source for defining disease cases and controls using ICD codes for PheWAS and genetic correlation studies [19] [27]. |

| Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) | A composite measure of an individual's genetic liability for a trait, calculated from GWAS summary statistics. | Serves as the "known cause" in the Causal Pivot model to detect additional variant contributions [21] [22]. |

| ClinVar Database | A public archive of reports of the relationships among human variations and phenotypes, with supporting evidence. | Curated source for identifying pathogenic/likely pathogenic rare variants for candidate causal analysis [21] [22]. |

| GWAS Summary Statistics | Publicly available results from genome-wide association studies, including effect sizes and p-values for millions of variants. | Used to calculate PRS and to perform genetic correlation analyses (e.g., with LD Score Regression) [20]. |

| Perturbation scRNA-seq Datasets | Single-cell transcriptomic data from controlled stimulation experiments on primary cells from multiple donors. | Enables mapping of context-specific genetic effects (reQTLs) and modeling of perturbation heterogeneity [26]. |

The intricate interplay between genetic heterogeneity and pleiotropy is a central theme in understanding the relationship between genotype and phenotype. The analytical frameworks and experimental protocols detailed here—including the Causal Pivot, the HVP model, and single-cell reQTL mapping—provide researchers with powerful tools to dissect this complexity. These approaches move beyond simple association to infer causality, distinguish between types of genetic effects, and capture dynamic regulation in specific cellular contexts.

For the field of drug development, these advances are transformative. They enable the stratification of patient populations based on underlying genetic etiology, even for phenotypically similar diseases, paving the way for more targeted and effective therapies. Furthermore, by clarifying whether a pleiotropic effect is vertical or horizontal, these methods help in assessing whether a potential drug target might influence a single pathway or have unintended consequences across multiple biological systems. As genomic biobanks continue to expand and single-cell technologies become more accessible, the integration of these sophisticated analytical frameworks will be indispensable for unraveling the genetic basis of human disease and translating these discoveries into precision medicine.

Pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) represents a severe myocardial disorder characterized by left ventricular dilation and impaired systolic function, serving as a leading cause of heart failure and sudden cardiac death in children. This case study examines the complex relationship between genetic determinants and clinical manifestations in pediatric DCM, highlighting the substantial genetic heterogeneity observed in this population. Through analysis of current literature and emerging methodologies, we demonstrate how precision medicine approaches are transforming diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment strategies for this challenging condition. The integration of advanced genetic testing with functional validation and multi-omics technologies provides unprecedented opportunities to decode genotype-phenotype relationships, enabling improved risk stratification and targeted therapeutic interventions for pediatric patients with DCM.

Clinical Significance and Genetic Landscape

Pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy is a severe myocardial disease characterized by enlargement of the left ventricle or both ventricles with impaired contractile function. This condition can lead to adverse clinical consequences including heart failure, sudden death, thromboembolism, and arrhythmias [28]. The annual incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy is approximately 1.13 per 100,000 children, with DCM representing one of the most common forms [29]. Over 100 genes have been linked to DCM, creating substantial diagnostic challenges but also opportunities for precision medicine approaches [28] [29].

The genetic architecture of pediatric DCM markedly differs from adult forms, characterized by early onset, rapid disease progression, and poorer prognosis [28]. Children with DCM display high genetic heterogeneity, with pathogenic variants identified in up to 50% of familial cases [29]. The major functional domains affected by these mutations include calcium handling, the cytoskeleton, and ion channels, which collectively disrupt normal cardiac function and structure [28].

Purpose and Scope

This case study aims to dissect the complex relationship between genetic variants and their clinical manifestations in pediatric DCM, framed within the broader context of genotype-phenotype relationship research. We will explore how genetic insights are transforming diagnostic approaches, prognostic stratification, and therapeutic development for this challenging condition. By examining current evidence and emerging methodologies, this analysis seeks to provide clinicians and researchers with a comprehensive framework for understanding and investigating genetic determinants of pediatric DCM.

Genetic Architecture of Pediatric DCM

Spectrum of Pathogenic Variants

The genetic landscape of pediatric DCM demonstrates considerable heterogeneity, with mutations identified across numerous genes encoding critical cardiac proteins. Current evidence indicates that disease-associated genetic variants play a significant role in the development of approximately 30-50% of pediatric DCM cases [30]. The table below summarizes the key genetic associations and their frequencies in pediatric DCM populations.

Table 1: Genetic Variants in Pediatric Dilated Cardiomyopathy

| Gene | Protein Function | Frequency in Pediatric DCM | Associated Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYH7 | Sarcomeric β-myosin heavy chain | 34.2% of genotype-positive cases [31] | Mixed cardiomyopathy phenotypes, progressive heart failure |

| MYBPC3 | Cardiac myosin-binding protein C | 12.2% of genotype-positive cases [31] | Hypertrophic features, arrhythmias |

| LMNA | Nuclear envelope protein (Lamin A/C) | Common in cardioskeletal forms [30] | Conduction system disease, skeletal myopathy, rapid progression |

| TTN | Sarcomeric scaffold protein | Significant proportion of familial cases [28] | Variable expressivity, age-dependent penetrance |

| DES | Muscle-specific intermediate filament | Associated with cardioskeletal myopathy [30] | Myopathy with cardiac involvement, conduction abnormalities |

Distinct Genetic Features in Pediatric Populations

Pediatric DCM demonstrates unique genetic characteristics that distinguish it from adult-onset disease. Children with DCM are more likely to have homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations, reflecting more severe genetic insults that manifest earlier in life [30]. Additionally, syndromic, metabolic, and neuromuscular causes represent a substantial proportion of pediatric cases, necessitating comprehensive evaluation for extracardiac features [30].

The genetic architecture of pediatric DCM also includes a higher prevalence of de novo mutations and variants in genes associated with severe, early-onset disease. For example, mutations in LMNA, which encodes a nuclear envelope protein, are frequently identified in pediatric DCM patients with associated skeletal myopathy and conduction system disease [30]. These mutations initially manifest with conduction abnormalities before progressing to DCM, illustrating the temporal dimension of genotype-phenotype correlations [30].

Methodological Approaches for Genotype-Phenotype Correlation Studies

Variant Identification and Interpretation

Establishing accurate genotype-phenotype correlations begins with comprehensive genetic testing and precise variant interpretation. Current guidelines by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) emphasize incorporating genetic evaluation into the standard care of pediatric cardiomyopathy patients [29]. The workflow for genetic variant analysis involves multiple validation steps to establish pathogenicity and clinical significance.

Table 2: Essential Methodologies for Genetic Analysis in Pediatric DCM

| Methodology | Application | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-generation sequencing panels | Simultaneous analysis of 100+ cardiomyopathy-associated genes [28] | Identification of P/LP variants, VUS | Coverage of known genes, but may miss novel associations |

| Whole exome sequencing | Broad capture of protein-coding regions beyond targeted panels [32] | Detection of variants in non-cardiomyopathy genes explaining syndromic features | Higher rate of VUS, increased interpretation challenges |

| ACMG/AMP guidelines | Standardized framework for variant classification [32] [29] | Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, VUS, Benign classifications | Requires integration of population data, computational predictions, functional data, segregation evidence |

| Familial cosegregation studies | Tracking variant inheritance in affected and unaffected family members [28] | Supports or refutes variant-disease association | Particularly important for VUS interpretation; may be limited by small family size |

| Transcriptomics and functional assays | Validation of putative pathogenic mechanisms [33] [34] | Evidence of RNA expression changes, protein alterations, cellular dysfunction | Provides mechanistic insights but requires specialized expertise |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for variant identification and interpretation in pediatric DCM research:

Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

Advanced methodologies integrating multiple data layers are increasingly critical for elucidating genotype-phenotype relationships in pediatric DCM. Mendelian randomization (MR) combined with Bayesian co-localization and single-cell RNA sequencing represents a powerful approach for identifying causal drug targets and molecular pathways [34]. This multi-omics framework enables researchers to move beyond association studies toward establishing causal relationships between genetic variants and disease mechanisms.

The integration of tissue-specific cis-expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) and protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) datasets from heart and blood tissues with genome-wide association studies (GWAS) data allows for robust identification of genes whose expression is causally associated with DCM [34]. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis further enables resolution of these associations at cellular levels, revealing cell-type-specific expression patterns in DCM hearts compared to controls [34].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated multi-omics approach:

Key Experimental Protocols

Systematic Variant Reinterpretation Framework

Variant reinterpretation has emerged as a critical component of genotype-phenotype correlation studies, with recent evidence demonstrating that approximately 21.6% of pediatric cardiomyopathy patients experience clinically meaningful changes in variant classification upon systematic reevaluation [32]. This protocol outlines a standardized approach for variant reassessment.

Protocol: Variant Reinterpretation Using Updated ACMG/AMP Guidelines

Data Collection: Compile original genetic test reports, clinical laboratory classifications, and patient phenotypic data.

Evidence Review:

- Query updated population frequency databases (gnomAD v4.1.0)

- Review recent ClinVar submissions (current through most recent release)

- Evaluate gene-disease validity using Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) curations

- Assess mutational hotspot and critical functional domain locations

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Apply computational prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, REVEL)

- Analyze conservation scores across species

- Evaluate splice site predictions

Segregation Analysis:

- Review familial genetic testing results when available

- Assess for de novo occurrence where parental testing exists

- Calculate logarithm of the odds (LOD) scores for large pedigrees

Functional Evidence Integration:

- Incorporate transcriptomic or proteomic data demonstrating molecular impact

- Consider relevant animal or cellular model data

- Evaluate therapeutic implications of variant reclassification

This systematic approach revealed that 10.9% of previously classified P/LP variants were downgraded to VUS, while 13.6% of VUS were upgraded to P/LP in pediatric cardiomyopathy cases [32]. The leading criteria for downgrading were high population allele frequency and variant location outside mutational hotspots or critical functional domains, while upgrades were primarily driven by variant location in mutational hotspots and deleterious in silico predictions [32].

Transcriptomic Analysis for Drug Repurposing

Transcriptomic profiling enables identification of gene expression signatures associated with specific genetic variants in pediatric DCM, creating opportunities for therapeutic repurposing. The following protocol outlines an approach combining in silico analysis with in vitro validation using patient-derived cells.

Protocol: Transcriptomic Analysis for Therapeutic Discovery

Gene Expression Profiling:

- RNA sequencing of patient-derived cardiomyocytes (LMNA-mutant vs. controls)

- Differential expression analysis (adjusted p-value < 0.05, fold-change > 1.5)

- Pathway enrichment analysis (Gene Ontology, KEGG, Reactome)

Computational Drug Screening:

- Query the Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures (LINCS)

- Identify compounds with inverse gene expression signatures to disease profile

- Prioritize FDA-approved drugs for repurposing candidates

In Vitro Validation:

- Generate patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs)

- Treat with identified candidate compounds (e.g., Olmesartan for LMNA-DCM)

- Assess functional endpoints: contractility, calcium handling, arrhythmia burden

- Measure reversal of disease-associated gene expression changes

This approach successfully identified Olmesartan as a candidate therapy for LMNA-associated DCM, demonstrating improved cardiomyocyte function, reduced abnormal rhythms, and restored gene expression in patient-derived cells [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pediatric DCM Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyopathy Gene Panels | Clinically validated multi-gene panels (100+ genes) [28] | Initial genetic screening | Comprehensive coverage of established cardiomyopathy genes; may miss novel associations |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Illumina platforms, Oxford Nanopore | Discovery of novel variants beyond panel genes | Higher VUS rate; requires robust bioinformatic pipeline |

| iPSC Differentiation Kits | Commercial cardiomyocyte differentiation kits | Generation of patient-specific cardiac cells | Variable efficiency across cell lines; require functional validation |

| Single-cell RNA Sequencing Platforms | 10X Genomics, Smart-seq2 | Cell-type-specific transcriptomic profiling | Cell dissociation effects on gene expression; computational expertise required |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Systems | SpCas9, base editors, prime editors | Functional validation of variants in cellular models | Off-target effects; require careful design and validation |

| Cardiac Functional Assays | Calcium imaging dyes, contractility measurements | Assessment of cardiomyocyte functional deficits | Technical variability; require appropriate controls |

| Bioinformatic Tools for Variant Interpretation | ANNOVAR, InterVar, VEP | Standardized variant classification | Dependence on updated databases; computational resource requirements |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Impact on Diagnosis and Prognosis

Establishing precise genotype-phenotype correlations in pediatric DCM has profound implications for clinical management. Genetic findings directly influence diagnostic accuracy, prognostic stratification, and family screening protocols. Studies demonstrate that children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a positive genetic test experience worse outcomes, including higher rates of extracardiac manifestations (38.1% vs. 8.3%), more frequent need for implantable cardiac defibrillators (23.8% vs. 0%), and higher transplantation rates (19.1% vs. 0%) compared to genotype-negative patients [31].

The high prevalence of variant reclassification (affecting 21.6% of patients) underscores the importance of periodic reevaluation of genetic test results [32]. These reinterpretations directly impact clinical care, requiring modification of family screening protocols through either initiation or discontinuation of clinical surveillance for genotype-negative family members [32].

Emerging Targeted Therapies

Advances in understanding genotype-phenotype relationships are driving the development of targeted therapies for genetic forms of DCM. Current approaches include:

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Mavacamten (Camzyos), a first-in-class cardiac myosin inhibitor, represents the first precision medicine for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, demonstrating that targeting sarcomere proteins can normalize cardiac function [35]. This approach is being explored for specific genetic forms of DCM.

Gene Therapy Strategies: Multiple gene therapy programs are advancing toward clinical application:

- TN-201: AAV9-based gene therapy for MYBPC3-associated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy currently in Phase 1b/2 trials (MyPEAK-1) [36]

- TN-401: AAV9-based gene therapy for PKP2-associated arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in Phase 1b trials (RIDGE-1) [36]

- RP-A501: AAV9-based gene therapy for Danon disease [37]

- NVC-001: AAV-based gene therapy for LMNA-related dilated cardiomyopathy with planned Phase 1/2 trial [37]

Drug Repurposing Approaches: Transcriptomic analysis has identified Olmesartan as a potential therapy for LMNA-associated DCM, demonstrating that existing medications may be redirected to treat specific genetic forms of cardiomyopathy [33].

The dissection of genotype-phenotype correlations in pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy represents a cornerstone of precision cardiology. Through systematic genetic testing, vigilant variant reinterpretation, and integration of multi-omics data, clinicians and researchers can unravel the complex relationship between genetic determinants and clinical manifestations in this heterogeneous disorder. These advances are already transforming clinical practice through improved diagnostic accuracy, refined prognostic stratification, and emerging targeted therapies. Future research must focus on functional validation of putative pathogenic variants, development of gene-specific therapies, and resolution of variants of uncertain significance, particularly in underrepresented populations. The continued integration of genetic insights into clinical management promises to improve outcomes for children with this challenging condition.

Bridging the Gap: AI, Machine Learning, and Novel Methodologies for Phenotype Prediction

The quest to quantitatively predict complex traits and diseases from genetic information represents a cornerstone of modern biology and precision medicine. For decades, the relationship between genotype and phenotype remained largely correlative, with limited predictive power for complex traits influenced by numerous genetic loci and environmental factors. The field has undergone a transformative evolution, moving from traditional statistical models to sophisticated artificial intelligence approaches. This paradigm shift began with the establishment of Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) as a robust statistical framework for genomic selection and has accelerated toward deep neural networks capable of modeling non-linear genetic architectures. The central challenge in this domain lies in developing models that can accurately capture the intricate relationships between high-dimensional genomic data and phenotypic outcomes, which may be influenced by epistatic interactions, pleiotropic effects, and complex biological pathways.

This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, methodological advancements, and practical implementations of predictive modeling in genomics. By providing a comprehensive analysis of both established and emerging approaches, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge necessary to select appropriate modeling strategies for specific genotype-phenotype prediction tasks across biological domains including plant and animal breeding, human genetics, and disease risk assessment.

Theoretical Foundations: From GBLUP to Deep Learning

Genomic BLUP: The Established Benchmark

Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) has served as a fundamental methodology in genomic prediction since its introduction. The method operates on a mixed linear model framework: y = 1μ + g + ε, where y represents the vector of phenotypes, μ is the overall mean, g is the vector of genomic breeding values, and ε represents residual errors [38]. The genomic values are assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution g ~ N(0, Gσ²g), where G is the genomic relationship matrix derived from marker data and σ²g is the genetic variance [38] [39].

The genomic relationship matrix G is constructed from marker genotypes, typically using the method described by VanRaden (2008), where G = ZZ′ / 2∑pk(1-pk), with Z representing a matrix of genotype scores centered by allele frequencies pk [38]. This relationship matrix enables GBLUP to capture three distinct types of quantitative-genetic information: linkage disequilibrium (LD) between quantitative trait loci (QTL) and markers, additive-genetic relationships between individuals, and cosegregation of linked loci within families [38] [40].

GBLUP's strength lies in its statistical robustness, computational efficiency, and interpretability, particularly for traits governed primarily by additive genetic effects [41] [39]. However, its linear assumptions limit its ability to capture complex non-linear genetic interactions, prompting the exploration of more flexible modeling approaches.

Deep Neural Networks: Modeling Complexity

Deep learning approaches, particularly multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), offer a powerful alternative for genomic prediction tasks. The fundamental MLP architecture for a univariate response can be represented as:

Yi = w₀⁰ + W₁⁰xᵢᴸ + ϵᵢ

where xᵢˡ = gˡ(w₀ˡ + W₁ˡxᵢˡ⁻¹) for l = 1,...,L, with xᵢ⁰ = xᵢ representing the input vector of markers for individual i [41]. The function gˡ denotes the activation function for layer l (typically ReLU for hidden layers), with w₀ˡ and W₁ˡ representing the bias vectors and weight matrices for each layer [41].

Unlike GBLUP, deep learning models can automatically learn hierarchical representations of genomic data and capture non-linear relationships and interactions without explicit specification [41] [42]. This flexibility makes them particularly suitable for traits with complex genetic architectures involving epistasis and gene-environment interactions. However, this increased modeling capacity comes with requirements for careful hyperparameter tuning and potential challenges in interpretation [41] [42].

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison Between GBLUP and Deep Learning Approaches

| Characteristic | GBLUP | Deep Neural Networks |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Linear mixed models | Multi-layer hierarchical representation learning |

| Genetic Architecture | Additive effects | Additive, epistatic, and non-linear effects |

| Computational Complexity | Lower (inversion of G-matrix) | Higher (gradient-based optimization) |

| Interpretability | High (variance components, breeding values) | Lower (black-box nature) |

| Data Requirements | Effective with moderate sample sizes | Generally requires larger training sets |

| Handling of Non-linearity | Limited | Excellent |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Empirical Evidence Across Biological Systems

Recent large-scale comparative studies have provided insights into the performance characteristics of GBLUP versus deep learning approaches across diverse genetic architectures and sample sizes. A comprehensive analysis across 14 real-world plant breeding datasets demonstrated that deep learning models frequently provided superior predictive performance compared to GBLUP, particularly in smaller datasets and for traits with suspected non-linear genetic architectures [41]. However, neither method consistently outperformed the other across all evaluated traits and scenarios, highlighting the importance of context-specific model selection [41].

In simulation studies with cattle SNP data, deep learning approaches demonstrated advantages for specific scenarios. A stacked kinship CNN approach showed 1-12% lower root mean squared error compared to GBLUP for additive traits and 1-9% lower RMSE for complex traits with dominance and epistasis [39]. However, GBLUP maintained higher Pearson correlation coefficients (0.672 for GBLUP vs. 0.505 for DNN in fully additive cases) [39], suggesting that the optimal metric for evaluation may influence model preference.

For human gene expression-based phenotype prediction, deep neural networks outperformed classical machine learning methods including SVM, LASSO, and random forests when large training sets were available (>10,000 samples) [42]. This performance advantage increased with training set size, highlighting the data-hungry nature of deep learning approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Studies and Biological Systems

| Study Context | Dataset Characteristics | GBLUP Performance | Deep Learning Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Breeding (14 datasets) [41] | Diverse crops; 318-1,403 lines; 2,038-78,000 SNPs | Variable across traits | Variable across traits; advantage in smaller datasets | Performance dependent on trait architecture; DL required careful parameter optimization |

| Cattle Simulation [39] | 1,033 Holstein Friesian; 26,503 SNPs; simulated traits | Correlation: 0.672 (additive) RMSE: Benchmark | Correlation: 0.505 (additive) RMSE: 1-12% lower | DL better RMSE, GBLUP better correlation; trade-offs depend on evaluation metric |

| Human Disease Prediction [42] | 54,675 probes; 27,887 tissues (cancer/non-cancer) | Not assessed | Accuracy advantage with large training sets (>10,000) | DL outperformed classical ML with sufficient data; interpretation challenges noted |

| Multi-omics Prediction [43] | Blood gene expression + methylation; 2,940 samples | Not assessed | AUC: 0.95 (smoking); Mean error: 5.16 years (age) | Interpretable DL successfully integrated multi-omics data |

Factors Influencing Model Performance

Several key factors emerge as critical determinants of predictive performance across modeling approaches:

Trait Complexity: Deep learning models demonstrate particular advantages for traits with non-additive genetic architectures, including epistatic interactions and dominance effects [39]. GBLUP remains highly effective for primarily additive traits.

Sample Size: The performance advantage of deep learning increases with training set size [42]. For moderate sample sizes, GBLUP often provides robust and competitive performance [41].

Marker Density: High marker density enables more accurate estimation of genomic relationships in GBLUP and provides richer feature representation for deep learning models [41] [39].

Data Representation: Innovative data representations, such as stacked kinship matrices transformed into image-like formats for CNN input, can enhance deep learning performance [39].

Methodological Implementation

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Standard GBLUP Implementation

The implementation of GBLUP follows a well-established statistical workflow:

Genotype Quality Control: Filter markers based on call rate, minor allele frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [39]. For cattle data, Wientjes et al. applied thresholds of call rate >95% and MAF >0.5% [39].

Genomic Relationship Matrix Calculation: Compute the G matrix using the method of VanRaden: G = ZZ′ / 2∑pk(1-pk), where Z is the centered genotype matrix [38] [39].

Phenotypic Data Preparation: Adjust phenotypes for fixed effects and experimental design factors. In plant breeding applications, Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUEs) are often computed to remove environmental effects [41].

Variance Component Estimation: Use restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to estimate genetic and residual variance components [38].

Breeding Value Prediction: Solve the mixed model equations to obtain genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for selection candidates [38].

Deep Learning Pipeline for Genomic Prediction

The implementation of deep learning models for genomic prediction requires careful attention to data preparation and model architecture:

Data Preprocessing:

Model Architecture Design:

Model Training:

Model Interpretation:

Visualization of Methodological Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows for GBLUP and deep learning approaches in genomic prediction:

Advanced Applications and Hybrid Approaches

Multi-omics Integration

The integration of multiple omics data types represents a promising application for advanced neural network architectures. Visible neural networks, which incorporate biological prior knowledge into their architecture, have demonstrated success in multi-omics prediction tasks [43]. These approaches connect molecular features to genes and pathways based on existing biological annotations, enhancing interpretability.

For example, in predicting smoking status from blood-based transcriptomics and methylomics data, a visible neural network achieved an AUC of 0.95 by combining CpG methylation sites with gene expression through gene-annotation layers [43]. This integration outperformed single-omics approaches and provided biologically plausible interpretations, highlighting known smoking-associated genes like AHRR, GPR15, and LRRN3 [43].

Interpretable Deep Learning

Addressing the "black box" nature of deep learning models remains an active research area. Several approaches have emerged to enhance interpretability in genomic contexts:

Visible Neural Networks: Architectures that incorporate biological hierarchies (genes → pathways → phenotypes) to maintain interpretability [43].

Gradient-Based Interpretation Methods: Techniques like Layerwise Relevance Propagation (LRP) and Integrated Gradients that quantify feature importance by backpropagating output contributions [42].

Biological Validation: Functional enrichment analysis of important features identified by models to verify biological relevance [42].

These approaches facilitate the extraction of biologically meaningful insights from complex deep learning models, bridging the gap between prediction and mechanistic understanding.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Genomic Prediction

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip [39], Affymetrix microarrays [42] | Genome-wide marker generation | Density, species specificity, cost |

| Sequencing Technologies | Next-generation sequencing (NGS) [45] [46] | Variant discovery, sequence-based genotyping | Coverage, read length, error profiles |

| Data Processing Tools | PLINK, GCTA, TASSEL | Quality control, relationship matrix calculation | Data format compatibility, scalability |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow [42], PyTorch | Model implementation and training | GPU support, community resources |

| Biological Databases | KEGG [43], GO, gnomAD [45] | Functional annotation, prior knowledge | Currency, species coverage, accessibility |

Future Directions and Implementation Recommendations

The field of genomic prediction continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. The development of hybrid models that combine the statistical robustness of GBLUP with the flexibility of deep learning represents a particularly promising avenue [41] [39]. Such approaches could leverage linear methods for additive genetic components while using neural networks to capture non-linear residual variation.

Transfer learning approaches, where models pre-trained on large genomic datasets are fine-tuned for specific applications, may help address the data requirements of deep learning while maintaining performance on smaller datasets [41]. Similarly, the incorporation of biological prior knowledge through visible neural network architectures shows promise for enhancing both performance and interpretability [43] [42].

For researchers implementing these approaches, we recommend the following strategy:

- Begin with GBLUP as a robust baseline, particularly for moderate-sized datasets and primarily additive traits [41].

- Explore deep learning approaches when non-linear genetic architectures are suspected or when integrating diverse data types [41] [43].

- Prioritize interpretability through biological validation and gradient-based interpretation methods, particularly for medical applications [42].

- Consider computational resources and expertise when selecting modeling approaches, as deep learning requires significant infrastructure and technical knowledge [41] [42].

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate modeling strategies based on research context:

As genomic technologies continue to advance, producing increasingly large and complex datasets, the evolution of predictive modeling approaches will remain essential for unlocking the relationship between genotype and phenotype. The complementary strengths of statistical and deep learning approaches provide a powerful toolkit for researchers addressing diverse challenges across biological domains.

The relationship between genotype (an organism's genetic makeup) and phenotype (its observable traits) represents one of the most fundamental challenges in modern biology. Understanding this relationship is particularly critical for advancing drug discovery, developing personalized treatments, and unraveling the mechanisms of complex diseases. Traditional statistical methods have provided valuable insights but often struggle to capture the nonlinear interactions, high-dimensional nature, and complex architectures of biological systems [44] [47]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative toolkit capable of addressing these challenges by detecting intricate patterns in large-scale biological datasets that conventional approaches might miss [48].

Machine learning approaches are especially valuable for integrating multimodal data—including genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical information—to build predictive models that bridge the gap between genetic variation and phenotypic expression [47]. The application of ML in genotype-phenotype research spans multiple domains, from identifying disease-associated genetic variants to predicting drug response and optimizing therapeutic interventions [44] [49]. This technical guide examines how supervised, unsupervised, and deep learning methodologies are being leveraged to advance our understanding of genotype-phenotype relationships, with particular emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research and development.

Machine Learning Fundamentals in Biological Context

Core Paradigms and Definitions