Functional Genomics Databases and Resources: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic guide to functional genomics databases and resources.

Functional Genomics Databases and Resources: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic guide to functional genomics databases and resources. It covers foundational databases for exploration, methodological applications in disease research and drug discovery, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing analyses, and finally, techniques for validating results and comparing resource utility. The guide integrates current tools and real-world applications to empower effective genomic data utilization in translational research.

Navigating the Core Landscape of Functional Genomics Databases

Genomic databases serve as the foundational infrastructure for modern biological research, enabling the storage, organization, and analysis of nucleotide and protein sequence data. These resources have transformed biological inquiry by providing comprehensive datasets that support everything from basic evolutionary studies to advanced drug discovery programs. Among these resources, four databases form the core of public genomic data infrastructure: GenBank, the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database, the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ), and the Reference Sequence (RefSeq) database. Understanding their distinct roles, interactions, and applications is essential for researchers navigating the landscape of functional genomics and drug development.

The International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) represents one of the most significant achievements in biological data sharing, creating a global partnership that ensures seamless access to publicly available sequence data. This collaboration, comprising GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ, synchronizes data daily to maintain consistent worldwide coverage [1] [2]. Alongside this archival system, the RefSeq database provides a curated, non-redundant set of reference sequences that serve as a gold standard for genome annotation, gene characterization, and variation analysis [3] [4]. Together, these resources provide the essential data backbone for functional genomics research, supporting both discovery-based science and applied pharmaceutical development.

Database Fundamentals and Architecture

The International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC)

The INSDC establishes the primary framework for public domain nucleotide sequence data through its three partner databases: GenBank (NCBI, USA), the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database (EBI, UK), and the DNA Data Bank of Japan (NIG, Japan) [1] [2]. This tripartite collaboration operates on a fundamental principle of daily data exchange, ensuring that submissions to any one database become automatically accessible through all three portals while maintaining consistent annotation standards and data formats [2] [5]. This synchronization mechanism creates a truly global resource that supports international research initiatives and eliminates redundant submission requirements.

The INSDC functions as an archival repository, preserving all publicly submitted nucleotide sequences without curatorial filtering or redundancy removal [3]. This inclusive approach captures the complete spectrum of sequence data, ranging from individual gene sequences to complete genomes, along with their associated metadata. The databases accommodate diverse data types, including whole genome shotgun (WGS) sequences, expressed sequence tags (ESTs), sequence-tagged sites (STS), high-throughput cDNA sequences, and environmental sequencing samples from metagenomic studies [2] [6]. This comprehensive coverage makes the INSDC the definitive source for primary nucleotide sequence data, forming the initial distribution point for many specialized molecular biology databases.

Table 1: International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration Members

| Database | Full Name | Host Institution | Location | Primary Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank | Genetic Sequence Database | National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) | Bethesda, Maryland, USA | NIH genetic sequence database, part of INSDC |

| EMBL | European Molecular Biology Laboratory Nucleotide Sequence Database | European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) | Hinxton, Cambridge, UK | Europe's primary nucleotide sequence resource |

| DDBJ | DNA Data Bank of Japan | National Institute of Genetics (NIG) | Mishima, Japan | Japan's nucleotide sequence database |

Reference Sequence (RefSeq): A Curated Alternative

The Reference Sequence (RefSeq) database represents a distinct approach to sequence data management, providing a curated, non-redundant set of reference standards derived from the INSDC archival records [3] [4]. Unlike the inclusive archival model of GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ, RefSeq employs sophisticated computational processing and expert curation to synthesize the current understanding of sequence information for numerous organisms. This synthesis creates a stable foundation for medical, functional, and comparative genomics by providing benchmark sequences that integrate data from multiple sources [3] [2].

RefSeq's distinctive character is immediately apparent in its accession number format, which utilizes a two-character underscore convention (e.g., NC000001 for a complete genomic molecule, NM000001 for an mRNA transcript, NP_000001 for a protein product) [3] [2]. This contrasts with the INSDC accession numbers that never include underscores. Additional distinguishing features include explicit documentation of record status (PROVISIONAL, VALIDATED, or REVIEWED), consistent application of official nomenclature, and extensive cross-references to external databases such as OMIM, Gene, UniProt, CCDS, and CDD [3]. These characteristics make RefSeq records particularly valuable for applications requiring standardized, high-quality reference sequences, such as clinical diagnostics, mutation reporting, and comparative genomics.

Table 2: RefSeq Accession Number Prefixes and Their Meanings

| Prefix | Molecule Type | Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| NC_ | Genomic | Complete genomic molecules | Chromosome references, complete genomes |

| NG_ | Genomic | Genomic regions | Non-transcribed pseudogenes, difficult-to-annotate regions |

| NM_ | Transcript | Curated mRNA | Mature messenger RNA transcripts with experimental support |

| NR_ | RNA | Non-coding RNA | Curated non-protein-coding transcripts |

| NP_ | Protein | Curated protein | Protein sequences with experimental support |

| XM_ | Transcript | Model mRNA | Predicted mRNA transcripts (computational annotation) |

| XP_ | Protein | Model protein | Predicted protein sequences (computational annotation) |

Technical Specifications and Data Structure

The Feature Table: A Universal Annotation Framework

The INSDC collaboration maintains data consistency through the implementation of a shared Feature Table Definition, which establishes common standards for annotation practice across all three databases [7] [8]. This specification, currently at version 11.3 (October 2024), defines the syntax and vocabulary for describing biological features within nucleotide sequences, creating a flexible yet standardized framework for capturing functional genomic elements [7]. The feature table format employs a tabular structure consisting of three core components: feature keys, locations, and qualifiers, which work in concert to provide comprehensive sequence annotation.

Feature keys represent the biological nature of annotated features through a controlled vocabulary that includes specific terms like "CDS" (protein-coding sequence), "reporigin" (origin of replication), "tRNA" (mature transfer RNA), and "proteinbind" (protein binding site on DNA) [7] [8]. These keys are organized hierarchically within functional families, allowing for both precise annotation of known elements and flexible description of novel features through "generic" keys prefixed with "misc" (e.g., miscRNA, misc_binding). The location component provides precise instructions for locating features within the parent sequence, supporting complex specifications including joins of discontinuous segments, fuzzy boundaries, and alternative endpoints. Qualifiers augment the core annotation with auxiliary information through a standardized system of name-value pairs (e.g., /gene="adhI", /product="alcohol dehydrogenase") that capture details such as gene symbols, protein products, functional classifications, and evidence codes [7].

Data Submission and Processing Workflows

The INSDC databases have established streamlined submission processes to accommodate contributions from diverse sources, ranging from individual researchers to large-scale sequencing centers. GenBank provides web-based submission tools (BankIt) for simple submissions and command-line utilities (table2asn) for high-volume submissions such as complete genomes and large batches of sequences [1] [6]. Similar submission pathways exist for EMBL and DDBJ, with all data flowing into the unified INSDC system through the daily synchronization process. Following submission, sequences undergo quality control procedures including vector contamination screening, verification of coding region translations, taxonomic validation, and bibliographic checks before public release [1] [9].

The RefSeq database employs distinct generation pipelines that vary by organism and data type. For many eukaryotic genomes, the Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline performs automated computational annotation that may integrate transcript-based records with computationally predicted features [3]. For a subset of species including human, mouse, rat, cow, and zebrafish, a curation-supported pipeline applies manual curation by NCBI staff scientists to generate records that represent the current consensus of scientific knowledge [3]. This process may incorporate data from multiple INSDC submissions and published literature to construct comprehensive representations of genes and their products. Additionally, RefSeq collaborates with external groups including official nomenclature committees, model organism databases, and specialized research communities to incorporate expert knowledge and standardized nomenclature [3].

Access Methods and Bioinformatics Applications

Database Querying and Sequence Retrieval

Researchers access genomic databases through multiple interfaces designed for different use cases and technical expertise levels. The Entrez search system provides text-based querying capabilities across NCBI databases, allowing users to retrieve sequences using accession numbers, gene symbols, organism names, or keyword searches [1] [3]. Search results can be filtered to restrict output to specific database subsets, such as limiting Nucleotide database results to only RefSeq records using the "srcdb_refseq[property]" query tag [3]. Programmatic access is available through E-utilities, which enable automated retrieval and integration of sequence data into software applications and analysis pipelines [1] [6].

The BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) family of algorithms represents the most widely used method for sequence similarity searching, allowing researchers to compare query sequences against comprehensive databases to identify homologous sequences and infer functional and evolutionary relationships [1] [6] [9]. NCBI provides specialized BLAST databases tailored to different applications, including the "nr" database for comprehensive searches, "RefSeq mRNA" or "RefSeq proteins" for curated references, and organism-specific databases for targeted analyses [3] [6]. For bulk data access, all databases provide FTP distribution sites offering complete dataset downloads in various formats, with RefSeq releases occurring every two months and incremental updates provided daily between major releases [1] [3] [4].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Genomic databases have become indispensable tools in modern drug development, particularly in the critical early stages of target identification and validation. Bioinformatics analyses leveraging these resources can significantly accelerate the identification of potential drug targets by enabling researchers to identify genes and proteins with specific functional characteristics, disease associations, and expression patterns relevant to particular pathologies [10] [9]. The integration of high-throughput data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics makes substantial contributions to mechanism-based drug discovery and drug repurposing efforts by establishing comprehensive molecular profiles of disease states and potential therapeutic interventions [10].

The application of genomic databases extends throughout the drug development pipeline. Molecular docking and virtual screening approaches use protein structure information derived from sequence databases to computationally evaluate potential drug candidates, prioritizing the most promising compounds for experimental validation [10]. In the realm of pharmacogenomics, these databases support the identification of genetic variants that influence individual drug responses, enabling the development of personalized treatment strategies that maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects [9]. Natural product drug discovery has been particularly transformed by specialized databases that catalog chemical structures, physicochemical properties, target interactions, and biological activities of natural compounds with anti-cancer potential [10]. These resources provide valuable starting points for the development of novel therapeutic agents, especially in oncology where targeted therapies have revolutionized treatment paradigms.

Table 3: Specialized Databases for Cancer Drug Development

| Database | URL | Primary Focus | Data Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| CancerResource | http://data-analysis.charite.de/care/ | Drug-target relationships | Drug sensitivity, genomic data, cellular fingerprints |

| canSAR | http://cansar.icr.ac.uk/ | Druggability assessment | Chemical probes, biological activity, drug combinations |

| NPACT | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/npact/ | Natural anti-cancer compounds | Plant-derived compounds with anti-cancer activity |

| PharmacoDB | https://pharmacodb.pmgenomics.ca/ | Drug sensitivity screening | Cancer datasets, cell lines, compounds, genes |

Experimental Protocols and Practical Implementation

Protocol 1: Submitting Sequences to GenBank Using BankIt

The BankIt system provides a web-based submission pathway for individual researchers depositing one or a few sequences to GenBank. Before beginning submission, researchers should prepare the following materials: complete nucleotide sequence in FASTA format, source organism information, author and institutional details, relevant publication information (if available), and annotations describing coding regions and other biologically significant features.

The submission protocol consists of five key stages: (1) Sequence entry through direct paste input or file upload, with automatic validation of sequence format; (2) Biological source specification using taxonomic classification tools and organism-specific data fields; (3) Annotation of coding sequences, RNA genes, and other features using the feature table framework; (4) Submitter information including contact details and release scheduling options; and (5) Final validation where GenBank staff perform quality assurance checks before assigning an accession number and releasing the record to the public database [1] [6]. For sequences requiring delayed publication to protect intellectual property, BankIt supports specified release dates while ensuring immediate availability once associated publications appear.

Protocol 2: Utilizing BLAST for Functional Annotation of Novel Sequences

The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) provides a fundamental method for inferring potential functions for newly identified sequences through homology detection. This protocol outlines the standard workflow for annotating a novel nucleotide sequence:

Sequence Preparation: Obtain the query sequence in FASTA format. For protein-coding regions, consider translating to amino acid sequence for more sensitive searches.

Database Selection: Choose an appropriate BLAST database based on research objectives. Options include:

- nr/nt: Comprehensive nucleotide database for general searches

- RefSeq mRNA: Curated transcript sequences for specific homolog identification

- Genome-specific databases: For organism-restricted searches

Parameter Configuration: Adjust search parameters including expect threshold (E-value), scoring matrices, and filters for low-complexity regions based on the specific application.

Result Interpretation: Analyze significant alignments (E-value < 0.001) for consistent domains, conserved functional residues, and phylogenetic distribution of homologs.

Functional Inference: Transfer putative functions from best-hit sequences while considering alignment coverage, identity percentages, and consistent domain architecture [6] [9].

This methodology enables researchers to quickly establish preliminary functional hypotheses for orphan sequences discovered through sequencing projects, guiding subsequent experimental validation strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Bioinformatics Reagents

Table 4: Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Resources for Genomic Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| BLAST Suite | Sequence similarity searching | Identifying homologous sequences, inferring gene function |

| Entrez Programming Utilities (E-utilities) | Programmatic database access | Automated retrieval of sequence data for analysis pipelines |

| ORF Finder | Open Reading Frame identification | Predicting protein-coding regions in novel sequences |

| Primer-BLAST | PCR primer design with specificity checking | Designing target-specific primers for experimental validation |

| Sequence Viewer | Graphical sequence visualization | Exploring genomic context and annotation features |

| VecScreen | Vector contamination screening | Detecting and removing cloning vector sequence from submissions |

| BioSample Database | Biological source metadata repository | Providing standardized descriptions of experimental materials |

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The ongoing expansion of genomic databases continues to enable new research paradigms in functional genomics and drug development. Several emerging trends are particularly noteworthy: the integration of multi-omics data layers creates unprecedented opportunities for understanding complex biological systems and disease mechanisms; the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to genomic datasets accelerates the identification of novel therapeutic targets; and the development of real-time pathogen genomic surveillance platforms exemplifies the translation of database resources into public health interventions [10] [9].

The NCBI Pathogen Detection Project represents one such innovative application, combining automated pipelines for clustering bacterial pathogen sequences with real-time data sharing to support public health investigations of foodborne disease outbreaks [6]. Similarly, the growth of the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) as a repository for next-generation sequencing data creates new opportunities for integrative analyses that leverage both raw sequencing reads and assembled sequences [6]. As biomedical research increasingly embraces precision medicine approaches, the role of genomic databases as central hubs for integrating diverse data types will continue to expand, supporting the development of targeted therapies tailored to specific molecular profiles and genetic contexts [10] [9].

Functional annotation is a cornerstone of modern genomics, enabling the systematic interpretation of high-throughput biological data. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of three pivotal resources in functional genomics: Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG, and Pfam. We detail their underlying frameworks, data structures, and practical applications while providing experimentally validated protocols for their implementation. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide integrates quantitative comparisons, visualization workflows, and essential reagent solutions to facilitate informed resource selection and experimental design in functional genomics research.

The post-genomic era has generated vast amounts of sequence data, creating an urgent need for systematic functional interpretation tools. Functional annotation resources provide the critical bridge between molecular sequences and their biological significance by categorizing genes and proteins according to their molecular functions, involved processes, cellular locations, and pathway associations. These resources form the foundational infrastructure for hypothesis generation, experimental design, and data interpretation across diverse biological domains.

Each major resource employs distinct knowledge representation frameworks: Gene Ontology (GO) provides a structured, controlled vocabulary for describing gene products across three independent aspects: molecular function, biological process, and cellular component [11]. KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) offers a database of manually drawn pathway maps representing molecular interaction and reaction networks [12]. Pfam is a comprehensive collection of protein families and domains based on hidden Markov models (HMMs) that enables domain-based functional inference [13]. Together, these resources create a multi-layered annotation system that supports everything from basic characterisation of novel genes to systems-level modeling of cellular processes.

Gene Ontology (GO): Framework and Applications

Core Structure and Annotation Principles

The Gene Ontology comprises three independent ontologies (aspects) that together provide a comprehensive descriptive framework for gene products: Molecular Function (MF) describes elemental activities at the molecular level, such as catalytic or binding activities; Biological Process (BP) represents larger processes accomplished by multiple molecular activities; and Cellular Component (CC) describes locations within cells where gene products are active [11]. Each ontology is structured as a directed acyclic graph where terms are nodes connected by defined relationships, allowing child terms to be more specialized than their parent terms while permitting multiple inheritance.

GO annotations are evidence-based associations between specific gene products and GO terms. The annotation process follows strict standards to ensure consistency and reliability across species [14]. Each standard GO annotation minimally includes: (1) a gene product identifier; (2) a GO term; (3) a reference source; and (4) an evidence code describing the type of supporting evidence [15]. A critical feature is the transitivity principle, where a positive annotation to a specific GO term implies annotation to all its parent terms, enabling hierarchical inference of gene function [15].

Table 1: Key Relations in Standard GO Annotations

| Relation | Application Context | Description |

|---|---|---|

| enables | Molecular Function | Links a gene product to a molecular function it executes |

| involved in | Biological Process | Connects a gene product to a biological process its molecular function supports |

| located in | Cellular Component | Indicates a gene product has been detected in a specific cellular anatomical structure |

| part of | Cellular Component | Links a gene product to a protein-containing complex |

| contributes to | Molecular Function | Connects a gene product to a molecular function executed by a macromolecular complex |

Advanced GO Frameworks: GO-CAM and the NOT Modifier

GO-CAM (GO Causal Activity Models) represents an evolution beyond standard annotations by providing a system to extend GO annotations with biological context and causal connections between molecular activities [15]. Unlike standard annotations where each statement is independent, GO-CAMs link multiple molecular activities through defined causal relations to model pathways and biological mechanisms. The fundamental unit in GO-CAM is the activity unit, which consists of a molecular function, the enabling gene product, and the cellular and biological process context where it occurs.

The NOT modifier is a critical qualification in GO annotations that indicates a gene product has been experimentally demonstrated not to enable a specific molecular function, not to participate in a particular biological process, or not to be located in a specific cellular component [15]. Importantly, NOT annotations are only used when users might reasonably expect the gene product to have the property, and they propagate in the opposite direction of positive annotations—downward to more specific terms rather than upward to parent terms.

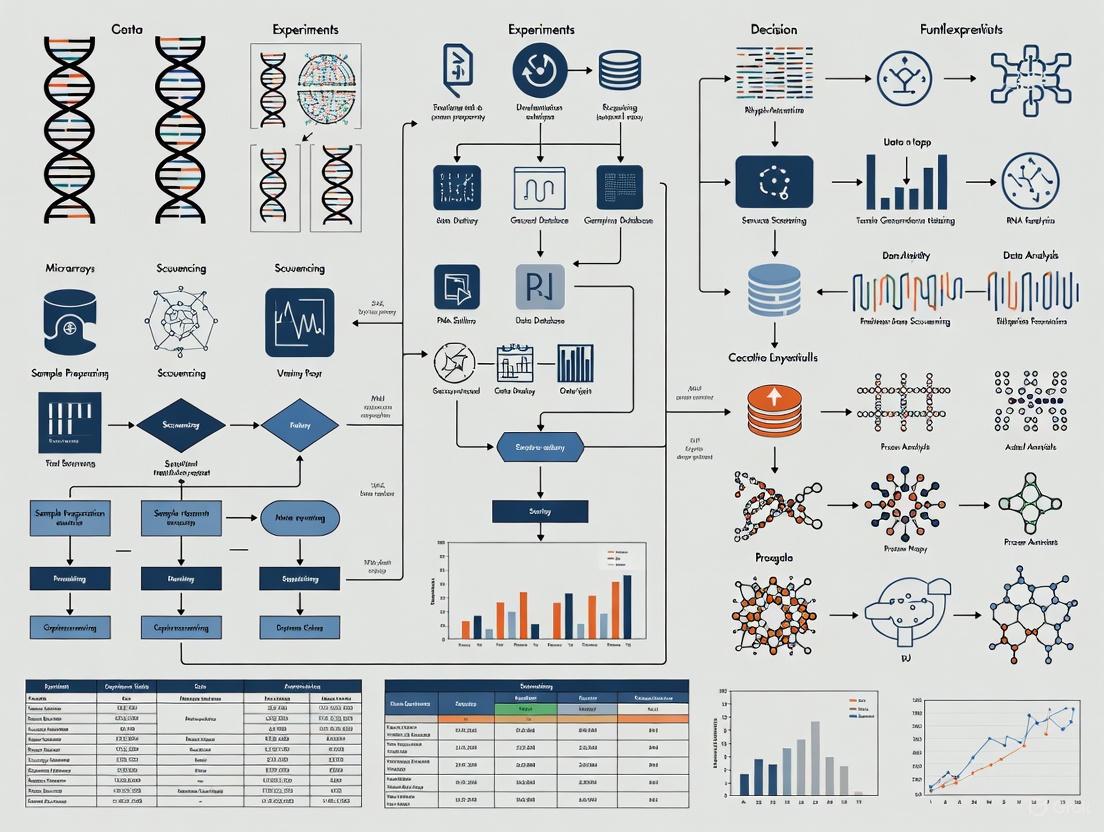

Figure 1: GO Annotation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of assigning GO annotations to gene products, from initial sequence data to final annotated output.

KEGG: Pathway-Based Annotation

Database Organization and Annotation System

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) is a database resource for understanding high-level functions and utilities of biological systems from molecular-level information [16]. The core of KEGG comprises three main components: (1) the GENES database containing annotated gene catalogs for sequenced genomes; (2) the PATHWAY, BRITE, and MODULE databases representing molecular interaction, reaction, and relation networks; and (3) the KO (KEGG Orthology) database containing ortholog groups that define functional units in the KEGG pathway maps [17].

KEGG pathway maps are manually drawn representations of molecular interaction networks that encompass multiple categories: metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, organismal systems, human diseases, and drug development [12]. Each pathway map is identified by a unique identifier combining a 2-4 letter prefix code and a 5-digit number, where the prefix indicates the map type (e.g., "map" for reference pathway, "ko" for KO-based reference pathway, and organism codes like "hsa" for Homo sapiens-specific pathways) [12].

Table 2: KEGG Pathway Classification with Representative Examples

| Pathway Category | Subcategory | Representative Pathway | Pathway Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | Global and overview maps | Carbon metabolism | 01200 |

| Metabolism | Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 00941 |

| Genetic Information Processing | Transcription | Basal transcription factors | 03022 |

| Environmental Information Processing | Signal transduction | MAPK signaling pathway | 04010 |

| Cellular Processes | Transport and catabolism | Endocytosis | 04144 |

| Organismal Systems | Immune system | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 04621 |

| Human Diseases | Neurodegenerative diseases | Alzheimer disease | 05010 |

KO-Based Annotation and Implementation

The foundation of KEGG annotation is the KO (KEGG Orthology) system, which assigns K numbers to ortholog groups that represent functional units in KEGG pathways [17]. Automatic KO assignment can be performed using KEGG Mapper tools or sequence similarity search tools like BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA, which facilitate functional annotation of genomic and metagenomic sequences [16]. The resulting KO assignments enable the reconstruction of pathways and inference of higher-order functional capabilities.

KEGG annotation extends beyond pathway mapping to include BRITE functional hierarchies and MODULE functional units, providing a multi-layered functional representation. Signature KOs and signature modules can be used to infer phenotypic features of organisms, enabling predictions about metabolic capabilities and other biological properties directly from genomic data [17].

Figure 2: KEGG Pathway Mapping Workflow. This diagram outlines the process of assigning KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers to gene sequences and subsequent pathway reconstruction for functional interpretation.

Pfam: Protein Domain Annotation

Database Structure and Domain Classification

Pfam is a database of protein families that includes multiple sequence alignments and hidden Markov models (HMMs) for protein domains [13]. The database classifies entries into several types: families (indicating general relatedness), domains (autonomous structural or sequence units found in multiple protein contexts), repeats (short units that typically form tandem arrays), and motifs (shorter sequence units outside globular domains) [13]. As of version 37.0 (June 2024), Pfam contains 21,979 families, providing extensive coverage of known protein domains.

For each family, Pfam maintains two key alignments: a high-quality, manually curated seed alignment containing representative members, and a full alignment generated by searching sequence databases with a profile HMM built from the seed alignment [13]. This two-tiered approach ensures quality while maximizing coverage. Each family has a manually curated gathering threshold that maximizes true matches while excluding false positives, maintaining annotation accuracy as the database grows.

Clan Architecture and Community Curation

A significant innovation in Pfam is the organization of related families into clans, which are groupings of families that share a single evolutionary origin, confirmed by structural, functional, sequence, and HMM comparisons [13]. As of version 32.0, approximately three-fourths of Pfam families belong to clans, providing important evolutionary context for protein domain annotation. Clan relationships are identified using tools like SCOOP (Simple Comparison Of Outputs Program) and information from external databases such as ECOD.

Pfam employs community curation through Wikipedia integration, allowing researchers to contribute and improve functional descriptions of protein families [13]. This collaborative approach helps maintain current and comprehensive annotations despite the rapid growth of sequence data. Pfam also specifically tracks Domains of Unknown Function (DUFs), which represent conserved domains with unidentified roles. As their functions are determined through experimentation, DUFs are systematically renamed to reflect their biological activities.

Table 3: Pfam Entry Types and Characteristics

| Entry Type | Definition | Coverage in Pfam | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Related sequences with common evolutionary origin | ~70% of entries | PF00001: 7 transmembrane receptor (rhodopsin family) |

| Domain | Structural/functional unit found in multiple contexts | ~20% of entries | PF00085: Thioredoxin domain |

| Repeat | Short units forming tandem repeats | ~5% of entries | PF00084: Sushi repeat/SCR domain |

| Motif | Short conserved sequence outside globular domains | ~5% of entries | PF00088: Anaphylatoxin domain |

| DUF | Domain of Unknown Function | Growing fraction | PF03437: DUF284 |

Comparative Analysis and Integration

Quantitative Comparison of Resource Scope

The three annotation resources differ significantly in their scope, data types, and coverage, making them complementary rather than redundant. GO provides the most comprehensive coverage of species, with annotations for >374,000 species including experimental annotations for 2,226 species [14]. KEGG offers pathway coverage with 537 pathway maps as of November 2025 [12], while Pfam covers 76.1% of protein sequences in UniProtKB with at least one Pfam domain [13].

Table 4: Comparative Analysis of Functional Annotation Resources

| Feature | Gene Ontology (GO) | KEGG | Pfam |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope | Gene product function, process, location | Pathways and molecular networks | Protein domains and families |

| Data Structure | Directed acyclic graph | Manually drawn pathway maps | Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) |

| Annotation Type | Terms with evidence codes | Ortholog groups (K numbers) | Domain assignments |

| Species Coverage | >374,000 species | KEGG organisms (limited taxa) | All kingdoms of life |

| Update Frequency | Continuous | Regular updates (Sept 2024) | Periodic version releases |

| Evidence Basis | Experimental, phylogenetic, computational | Manual curation with genomic context | Sequence similarity, HMM thresholds |

| Key Access Methods | AmiGO browser, annotation files | KEGG Mapper, BlastKOALA | InterPro website, HMMER |

Integrated Annotation Workflow

In practice, these resources are often used together in a complementary workflow. A typical integrated annotation pipeline begins with domain identification using Pfam to establish potential functional units, proceeds to GO term assignment for standardized functional description, and culminates in pathway mapping using KEGG to establish systemic context. This multi-layered approach provides robust functional predictions that leverage the unique strengths of each resource.

Figure 3: Integrated Functional Annotation Pipeline. This workflow demonstrates how GO, KEGG, and Pfam complement each other in a comprehensive protein annotation strategy.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Transcriptome Analysis Protocol for Biosynthetic Pathways

The application of these annotation resources is exemplified in transcriptomic studies of specialized metabolite biosynthesis. The following protocol, adapted from Frontiers in Bioinformatics (2025), details an integrated approach for identifying genes involved in triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis in Hylomecon japonica [18]:

Step 1: RNA Extraction and Sequencing

- Collect fresh plant tissues (leaves, roots, stems) and immediately freeze in liquid nitrogen

- Extract total RNA using commercial kits (e.g., Omega Bio-Tek)

- Assess RNA purity (Nanodrop), concentration, and integrity (Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer)

- Construct cDNA library using mRNA enrichment and rRNA removal methods

- Sequence using DNA nanoball sequencing (DNB-seq) platform

Step 2: Data Processing and Assembly

- Filter raw reads using SOAPnuke (v1.5.2) to remove adapters, low-quality reads, and reads with >10% unknown bases

- Assemble clean reads using Trinity (v2.0.6) to generate transcripts

- Cluster and deduplicate transcripts using CD-HIT (v4.6) to obtain unigenes

Step 3: Functional Annotation

- Annotate unigenes against seven databases: NR, NT, SwissProt, KOG, KEGG, GO, and Pfam

- Use hmmscan (v3.0) for Pfam domain identification

- Employ Blast2GO (v2.5.0) for GO term assignment

- Calculate gene expression levels using Bowtie2 and RSEM with FPKM normalization

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using Poisson distribution methods

Step 4: Targeted Pathway Analysis

- Identify key enzyme genes in the triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis pathway

- Analyze transcription factors using getorf and hmmsarch against PlantTFDB

- Model protein structures (e.g., squalene synthase) using ExPASy and ESPrip

- Construct phylogenetic trees using MEGA and CLUSTALX

This protocol successfully identified 49 unigenes encoding 11 key enzymes in triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis and nine relevant transcription factors, demonstrating the power of integrated functional annotation [18].

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Functional Annotation

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit (Omega Bio-Tek) | High-quality RNA isolation for transcriptome sequencing | Alternative: TRIzol method, Qiagen RNeasy kits |

| DNB-seq Platform | DNA nanoball sequencing for transcriptome analysis | Alternative: Illumina NovaSeq X, Oxford Nanopore |

| Trinity Software (v2.0.6) | De novo transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data | Reference: Haas et al., 2023 [18] |

| HMMER Software Suite | Profile hidden Markov model searches for Pfam annotation | Usage: hmmscan for domain detection [13] |

| Blast2GO (v2.5.0) | Automated GO term assignment and functional annotation | Reference: Conesa et al., 2005 [18] |

| KEGG Mapper | Reconstruction of KEGG pathways from annotated sequences | Access: KEGG website tools [17] |

| Bowtie2 & RSEM | Read alignment and expression quantification | Implementation: FPKM normalization [18] |

| InterPro Database | Integrated resource including Pfam domains | Access: EBI website [13] |

Gene Ontology, KEGG, and Pfam represent foundational infrastructure for functional genomics, each contributing unique strengths to biological interpretation. GO provides a standardized framework for describing gene functions, processes, and locations across species. KEGG offers pathway-centric annotation that places genes in the context of systemic networks. Pfam delivers deep protein domain analysis that reveals evolutionary relationships and functional modules. Their integrated application, as demonstrated in the transcriptome analysis protocol, enables comprehensive functional characterization that supports advancements in basic research, biotechnology, and drug development. As functional genomics evolves, these resources continue to adapt—incorporating new biological knowledge, improving computational methods, and expanding species coverage to meet the challenges of interpreting increasingly complex genomic data.

Functional genomics relies on specialized databases to decipher the roles of genes and proteins across diverse organisms. Orthology and protein family databases provide the foundational framework for predicting gene function, understanding evolutionary relationships, and elucidating molecular mechanisms. These resources are indispensable for translating genomic sequence data into biological insights with applications across biomedical and biotechnological domains. This technical guide examines three essential resources: eggNOG for orthology-based functional annotation, Resfams for antibiotic resistance profiling, and dbCAN for carbohydrate-active enzyme characterization. Each database employs distinct methodologies to address specific challenges in functional genomics, enabling researchers to annotate genes, predict protein functions, and explore biological systems at scale.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of eggNOG, Resfams, and dbCAN

| Feature | eggNOG | Resfams | dbCAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Orthology identification & functional annotation | Antibiotic resistance protein families | Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes (CAZymes) |

| Classification Principle | Evolutionary genealogy & orthologous groups | Protein family HMMs with antibiotic resistance ontology | Family & subfamily HMMs based on CAZy database |

| Key Methodology | Hierarchical orthology inference & phylogeny | Curated hidden Markov models (HMMs) | Integrated HMMER, DIAMOND, & subfamily HMMs |

| Coverage Scope | Broad: across 5090 organisms & 2502 viruses [19] [20] | Specific: 166 profile HMMs for major antibiotic classes [21] | Specific: >800 HMMs (families & subfamilies); updated annually [22] |

| Unique Strength | Avoids annotation transfer from close paralogs [20] | Optimized for metagenomic resistome screening with high precision [21] | Predicts glycan substrates & identifies CAZyme gene clusters [22] [23] |

| Typical Application | Genome-wide functional annotation [19] [20] | Identification of resistance determinants in microbial genomes [19] [21] | Analysis of microbial carbohydrate metabolism & bioenergy [19] [22] |

eggNOG: Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes

Core Principles and Framework

The eggNOG (evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups) database provides a comprehensive framework for orthology analysis and functional annotation across a wide taxonomic spectrum. The resource is built on a hierarchical classification system that organizes genes into orthologous groups (OGs) at multiple taxonomic levels, including prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and viral clades [19]. This structure enables researchers to infer gene function based on evolutionary conservation and to trace functional divergence across lineages. eggNOG's value proposition lies in its use of fine-grained orthology for functional transfer, which provides higher precision than traditional homology searches (e.g., BLAST) by avoiding annotation transfer from close paralogs that may have undergone functional divergence [20].

Annotation Methodology and Workflow

Figure 1: eggNOG-mapper Functional Annotation Workflow

The eggNOG-mapper tool implements this orthology-based annotation approach through a multi-step process. The workflow begins with query sequences (nucleotide or protein), which are searched against precomputed orthologous groups and phylogenies from the eggNOG database using fast search algorithms such as HMMER or DIAMOND [20]. The system then assigns sequences to fine-grained orthologous groups based on evolutionary relationships. Finally, functional annotations—including Gene Ontology (GO) terms, KEGG pathways, and enzyme classification (EC) numbers—are transferred from the best-matching orthologs within the assigned groups [19] [20]. This method is particularly valuable for annotating novel genomes, transcriptomes, and metagenomic gene catalogs with high accuracy.

Resfams: Antibiotic Resistance Profiling

Database Structure and Validation

Resfams is a curated database of protein families and associated profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) specifically designed for identifying antibiotic resistance genes in microbial sequences. The core database was constructed by training HMMs on unique antibiotic resistance protein sequences from established sources including the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), the Lactamase Engineering Database (LacED), and a curated collection of beta-lactamase proteins [21]. This core was supplemented with additional HMMs from Pfam and TIGRFAMs that were experimentally verified through functional metagenomic selections of soil and human gut microbiota [21].

The current version of Resfams contains 166 profile HMMs representing major antibiotic resistance gene classes, including defenses against beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, glycopeptides, macrolides, and tetracyclines, along with efflux pumps and transcriptional regulators [21]. Each HMM has been optimized with profile-specific gathering thresholds to establish inclusion bit score cut-offs, achieving nearly perfect precision (99 ± 0.02%) and high recall for independent antibiotic resistance proteins not used in training [21].

Experimental Workflow for Resistome Analysis

Figure 2: Resfams-Based Antibiotic Resistance Analysis

The standard analytical protocol for resistome characterization using Resfams begins with gene prediction from microbial genomes or metagenomic assemblies using tools like Prodigal. The resulting protein sequences are then searched against the Resfams HMM database using HMMER. Researchers must select the appropriate database version: the Core database for general annotation without functional confirmation, or the Full database when previous functional evidence of antibiotic resistance exists (e.g., from functional metagenomic selections) [21]. The search results are filtered using optimized bit score thresholds to ensure high precision. Compared to BLAST-based approaches against ARDB and CARD, Resfams demonstrates significantly improved sensitivity, identifying 64% more antibiotic resistance genes in soil and human gut microbiota studies while maintaining zero false positives in validation tests [21].

dbCAN: Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme Annotation

Database Architecture and Substrate Prediction

dbCAN is a specialized resource for annotating carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in genomic and metagenomic datasets. The database employs a multi-tiered classification system that organizes enzymes into families based on catalytic activities: glycoside hydrolases (GHs), glycosyl transferases (GTs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs), and auxiliary activities (AAs) [22] [24]. A key innovation in dbCAN3 is its capacity for substrate prediction, enabling researchers to infer the specific glycan substrates that CAZymes target [22] [23].

The annotation pipeline integrates three complementary methods: HMMER search against the dbCAN CAZyme domain HMM database, DIAMOND search for BLAST hits in the CAZy database, and HMMER search for CAZyme subfamily annotation using the dbCAN-sub HMM database [22]. This multi-algorithm approach increases annotation confidence and coverage. The database is updated annually to incorporate the latest CAZy database releases, with recent versions containing over 800 CAZyme HMMs covering both families and subfamilies [22].

CAZyme Gene Cluster Identification

Figure 3: dbCAN Workflow for CGC Identification & Substrate Prediction

A distinctive feature of dbCAN is its ability to identify CAZyme Gene Clusters (CGCs)—genomic loci where CAZyme genes are co-localized with other genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, such as transporters, regulators, and accessory proteins [25]. The dbCAN pipeline incorporates CGCFinder to detect these clusters by analyzing gene proximity and functional associations [25]. For CGC substrate prediction, dbCAN3 implements two complementary approaches: dbCAN-PUL homology search, which compares query CGCs to experimentally characterized Polysaccharide Utilization Loci (PULs), and dbCAN-sub majority voting, which infers substrates based on the predominant substrate annotations of subfamily HMMs within the cluster [22] [23]. These methods have been applied to nearly 500,000 CAZymes from 9,421 metagenome-assembled genomes, providing substrate predictions for approximately 25% of identified CGCs [23].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMMER [21] [20] | Software Suite | Profile HMM searches for protein family detection | Identifying domain architecture & protein families (Resfams, dbCAN, eggNOG) |

| DIAMOND [22] [20] | Sequence Aligner | High-speed BLAST-like protein sequence search | Large-scale sequence comparison against reference databases |

| CARD [19] [21] | Curated Database | Reference data for antibiotic resistance genes | Training set and validation resource for Resfams |

| CAZy Database [22] [24] | Curated Database | Expert-curated CAZyme family classification | Foundation for dbCAN HMM development and validation |

| run_dbcan [22] [25] | Software Package | Automated CAZyme annotation & CGC detection | Command-line implementation of dbCAN pipeline |

| eggNOG-mapper [20] | Web/Command Tool | Functional annotation via orthology assignment | Genome-wide gene function prediction |

| Prodigal [20] | Software Tool | Prokaryotic gene prediction | Identifying protein-coding genes in microbial sequences |

eggNOG, Resfams, and dbCAN represent specialized approaches to the challenge of functional annotation in genomics. eggNOG provides broad orthology-based functional inference across the tree of life, Resfams enables precise identification of antibiotic resistance determinants with minimal false positives, and dbCAN offers detailed characterization of carbohydrate-active enzymes and their metabolic contexts. As sequencing technologies continue to generate vast amounts of genomic data, these resources will remain essential for translating genetic information into biological understanding, with significant implications for drug development, microbial ecology, and biotechnology. Future developments will likely focus on expanding substrate predictions for uncharacterized protein families, improving integration between databases, and enhancing scalability for large-scale metagenomic analyses.

The completion of genome sequencing for numerous agriculturally important species revealed a critical bottleneck: the transition from raw sequence data to biological understanding. Agricultural species, including livestock and crops, provide food, fiber, xenotransplant tissues, biopharmaceuticals, and serve as biomedical models [26] [27]. Many of their pathogens are also human zoonoses, increasing their relevance to human health. However, compared to model organisms like human and mouse, agricultural species have suffered from significantly poorer structural and functional annotation of their genomes, a consequence of smaller research communities and more limited funding [26] [27] [28].

The AgBase database (http://www.agbase.msstate.edu) was established as a curated, web-accessible, public resource to address this exact challenge [26] [27]. It was the first database dedicated to functional genomics and systems biology analysis for agriculturally important species and their pathogens [26]. Its primary mission is to facilitate systems biology by providing both computationally accessible structural annotation and, crucially, high-quality functional annotation using the Gene Ontology (GO) [28]. By integrating these resources into an easy-to-use pipeline, AgBase empowers agricultural and biomedical researchers to derive biological significance from functional genomics datasets, such as microarray and proteomics data [27].

Resource Architecture and Technical Implementation

Database Construction and Design Principles

AgBase was constructed with a clear focus on the unique needs of the agricultural research community. The underlying technical infrastructure is built on a server with a dual Xeon 3.0 processor, 4 GB of RAM, and a RAID-5 storage configuration, running on the Windows 2000 Server operating system [26] [27]. The database is implemented using the mySQL 4.1 database management system, with NCBI Blast and custom scripts written in Perl CGI for functionality [26].

The database schema is protein-centric and represents an adaptation of the Chado schema, a modular database design for biological data, with extensions to accommodate the storage of expressed peptide sequence tags (ePSTs) derived from proteogenomic mapping [26] [27]. AgBase follows a multi-species database paradigm and is focused on plants, animals, and microbial pathogens that have significant economic impact on agricultural production or are zoonotic diseases [26]. A key design philosophy of AgBase is the use of standardized nomenclature based on the Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature guidelines, promoting consistency and data integration across species [26] [27].

Data Integration and Content Management

AgBase synthesizes both internally generated and external data. In-house data includes manually curated GO annotations and experimentally derived ePSTs [26]. Externally, the database integrates the Gene Ontology itself, the UniProt database, GO annotations from the EBI GOA project, and taxonomic information from the NCBI Entrez Taxonomy [26]. This integration provides users with a unified view of available functional information. The system is updated from these external sources every three months, while locally generated data is loaded continuously as it is produced [26]. To facilitate data exchange and reuse, gene association files containing all gene products annotated by AgBase are accessible in a tab-delimited format for download [26] [28].

Table: AgBase Technical Architecture Overview

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Dual Xeon 3.0 processor, 4 GB RAM, RAID-5 storage | Core computational and storage platform |

| Database System | MySQL 4.1 | Data management and query processing |

| Core Technologies | NCBI Blast, Perl CGI | Sequence analysis and web interface scripting |

| Data Schema | Adapted Chado schema | Protein-centric data organization with ePST extensions |

| Update Cycle | External sources quarterly; local data continuously | Ensures data currency |

Methodologies for Genomic Annotation

Experimental Structural Annotation via Proteogenomic Mapping

A fundamental aim of AgBase is to improve the structural annotation of agricultural genomes through experimental validation. Initial genome annotations rely heavily on computational predictions, which can have false positive and false negative rates as high as 70% [28]. AgBase addresses this via proteogenomic mapping, a method that uses high-throughput mass spectrometry-based proteomics to provide direct in vivo evidence for protein expression [27] [28].

The proteogenomic mapping pipeline, implemented in Perl, identifies novel protein fragments from experimental proteomics data and aligns them to the genome sequence [26] [27]. These aligned sequences are extended to the nearest 3' stop codon to generate expressed Peptide Sequence Tags (ePSTs) [27] [28]. The results are visualized using the Apollo genome browser, allowing for manual curation and quality checking by AgBase biocurators [26]. This methodology has proven highly effective. For instance, in the prokaryotic pathogen Pasteurella multocida (a cause of fowl cholera and bovine respiratory disease), the pipeline identified 202 novel ePSTs with recognizable start codons, including a 130-amino-acid protein in a previously annotated intergenic region [27]. This demonstrates the power of this experimental approach in refining and validating genome structure.

Functional Annotation Using the Gene Ontology (GO)

For functional annotation, AgBase employs the Gene Ontology (GO), which is the de facto standard for representing gene product function [26] [28]. GO annotations in AgBase are generated through two primary methods:

- Manual Curation: Expert biocurators, trained in formal GO curation courses, annotate gene products based on experimental evidence from the peer-reviewed literature. All such annotations are quality-checked to meet GO Consortium standards [26].

- Sequence Similarity: The GOanna tool is used for annotations "inferred from sequence similarity" (ISS). GOanna performs BLAST searches against user-selected databases of GO-annotated proteins. The resulting alignments are manually inspected to ensure reliability before the ISS annotation is assigned [26] [29].

A critical innovation of AgBase is its two-tier system for GO annotations, which allows users to choose between maximum reliability or maximum coverage [28]:

- The GO Consortium gene association file contains only the most rigorous annotations based on experimental data.

- The Community gene association file includes additional annotations from expert community knowledge, author statements, predicted proteins, and ISS annotations that may not meet the strictest current GO Consortium evidence standards.

This system acknowledges the evolving nature of functional annotation while providing a transparent framework for researchers to select data appropriate for their analysis.

Table: Two-Tiered GO Annotation System in AgBase

| Annotation Tier | Content | Quality Control | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO Consortium File | Annotations based solely on experimental evidence | Fully quality-checked to GO Consortium standards | High-reliability analyses (e.g., publication) |

| Community File | Annotations from community knowledge, author statements, predicted proteins, and some ISS | Checked for formatting errors only | Maximum coverage and exploratory analysis |

Analytical Tools and Workflows

The Functional Genomics Analysis Pipeline

AgBase provides a suite of integrated computational tools designed to support the analysis of large-scale functional genomics datasets. These tools are designed to work together in a cohesive pipeline, enabling researchers to move seamlessly from a list of gene identifiers to biological interpretation [26] [28].

The core tools in this pipeline are:

- GORetriever: This tool accepts a list of database identifiers (e.g., from a microarray experiment) and retrieves all existing GO annotations for those proteins from designated databases. It returns the data in multiple formats, including a downloadable Excel file and a simplified GO Summary file for use in the next tool [28].

- GOanna: For proteins without existing GO annotations, GOanna performs BLAST searches against a user-defined database of GO-annotated proteins (e.g., AgBase Community, SwissProt, or species-specific databases) [28] [29]. It returns potential orthologs with their GO annotations, which the researcher can then manually evaluate and transfer based on sequence similarity [28].

- GOSlimViewer: This tool uses the GO Summary file from GORetriever to map the dataset onto higher-level, broad functional categories (GO slims). This provides a statistical overview of the biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components that are over- or under-represented in the experimental dataset, facilitating high-level interpretation [28].

Proteomics Support Tools

Beyond transcriptomic analysis, AgBase offers specialized tools for proteomics research. The proteogenomic pipeline, as described previously, is available for generating ePSTs and improving genome structural annotation [27] [28]. Additionally, the ProtIDer tool assists with proteomic analysis in species that lack a sequenced genome. It creates a database of highly homologous proteins from Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) and EST assemblies, which can then be used to identify proteins from mass spectrometry data [28]. AgBase also provides a GOProfiler tool, which gives a statistical summary of existing GO annotations for a given species, helping researchers understand the current state of functional knowledge for their organism of interest [28].

To effectively utilize AgBase and conduct functional genomics research in agricultural species, researchers rely on a collection of key bioinformatics resources and reagents. The following table details these essential components.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural Functional Genomics

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to AgBase |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOanna Databases [29] | Bioinformatics Database | Provides a target for sequence similarity searches (BLAST) to transfer GO annotations from annotated proteins to query sequences. | Core to the ISS annotation process; includes general (UniProt, AgBase Community) and species-specific (Chick, Cow, Sheep, etc.) databases. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [26] [28] | Controlled Vocabulary | Provides standardized terms (and their relationships) for describing gene product functions across three domains: Biological Process, Molecular Function, and Cellular Component. | The foundational framework for all functional annotations within AgBase. |

| UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) [26] | Protein Sequence Database | A central repository of expertly curated (Swiss-Prot) and automatically annotated (TrEMBL) protein sequences. | A primary source of protein sequences and existing GO annotations imported into AgBase. |

| Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) [26] [28] | Experimental Data | Short sub-sequences of cDNA molecules, used as evidence for gene expression and to aid in gene discovery and structural annotation. | Used by the ProtIDer tool to create databases for proteomic identification in non-model species. |

| Proteomics Data (Mass Spectrometry) [27] [28] | Experimental Data | Experimental data identifying peptide sequences derived from proteins expressed in vivo. | The raw material for the proteogenomic mapping pipeline, generating ePSTs for experimental structural annotation. |

| NCBI Taxonomy [26] | Classification Database | A standardized classification of organisms, each with a unique Taxon ID. | Used to organize AgBase by species and to build species-specific databases and search tools. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

AgBase represents a critical community-driven solution to the challenges of functional genomics in agricultural species. By providing high-quality, experimentally supported structural and functional annotations, along with a suite of accessible analytical tools, it empowers researchers to move beyond simple sequence data to meaningful biological insight. The resource is directly relevant not only to agricultural production but also to diverse fields such as cancer biology, biopharmaceuticals, and evolutionary biology, given the role of many agricultural species as biomedical models [26].

The core challenges that motivated AgBase's creation—smaller research communities and less funding compared to human and mouse research—necessitate a collaborative approach. AgBase's two-tiered annotation system and its mechanism for accepting and acknowledging community submissions are designed to foster such collaboration [26] [28]. As the volume of functional genomics data continues to grow, resources like AgBase will become increasingly vital for integrating this information and enabling systems-level modeling. The experimental methods and bioinformatics tools developed for AgBase are not only applicable to agricultural species but also serve as valuable models for functional annotation efforts in other non-model organisms [26]. Through continued curation and community engagement, AgBase will remain a cornerstone for advancing functional genomics in agriculture.

Within the field of functional genomics, genome browsers are indispensable tools that provide an interactive window into the complex architecture of genomes. They enable researchers to visualize and interpret a vast array of genomic annotations—from genes and regulatory elements to genetic variants—in an integrated genomic context. The UCSC Genome Browser and Ensembl stand as two of the most pivotal and widely used resources in this domain. While both serve the fundamental purpose of genomic data visualization, their underlying philosophies, data sources, and tooling ecosystems differ significantly. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of these two platforms, framed within the context of functional genomics databases and resources. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select and utilize the appropriate browser for their specific research needs, from exploratory data analysis to clinical variant interpretation.

The distinct utility of the UCSC Genome Browser and Ensembl stems from their foundational design principles and data aggregation strategies.

The UCSC Genome Browser, developed and maintained by the University of California, Santa Cruz, operates on a "track" based model [30]. This architecture is designed to aggregate a massive collection of externally and internally generated annotation datasets, making them viewable as overlapping horizontal lines on a genomic coordinate system. UCSC functions as a central hub, curating and hosting data from a wide variety of sources, including RefSeq, GENCODE, and numerous independent research consortia like the Consortium of Long Read Sequencing (CoLoRS) [30]. This approach provides researchers with a unified view of diverse data types. Recent developments highlight its commitment to integrating advanced computational analyses, such as tracks from Google DeepMind's AlphaMissense model for predicting pathogenic missense variants and VarChat tracks that use large language models to condense scientific literature on genomic variants [31].

In contrast, Ensembl, developed by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory's European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, is built around an integrated and automated genome annotation pipeline [32] [33]. While it also displays externally generated data, a core strength is its own systematic gene builds, which produce definitive gene sets for a wide range of organisms. Ensembl assigns unique Ensembl gene IDs (e.g., ENSG00000123456) and focuses on providing a consistent and comparative genomics framework across species [32]. Its annotation is comprehensive, with one study noting that Ensembl's broader gene coverage resulted in a significantly higher RNA-Seq read mapping rate (86%) compared to RefSeq and UCSC annotations (69-70%) in a "transcriptome only" mapping mode [34].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of UCSC Genome Browser and Ensembl

| Feature | UCSC Genome Browser | Ensembl |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Affiliation | University of California, Santa Cruz [32] | EMBL-EBI & Wellcome Sanger Institute [32] |

| Core Data Model | Track-based hub [30] | Integrated annotation pipeline [32] |

| Primary Gene ID System | UCSC Gene IDs (e.g., uc001aak.4) [32] |

Ensembl Gene IDs (e.g., ENSG00000123456) [32] |

| Key Gene Annotation | GENCODE "knownGene" (default track) [30] | Ensembl Gene Set [32] |

| Update Strategy | Frequent addition of new tracks and data from diverse sources [30] | Regular versioned releases with updated gene builds [33] |

| Notable Recent Features | AlphaMissense, VarChat, CoLoRSdb, SpliceAI Wildtype tracks [30] [31] | Expansion of protein-coding transcripts and new breed-specific genomes [33] |

Comparative Analysis of Features and Tools

A deeper examination of the platforms' functionalities reveals distinct strengths suited for different analytical workflows.

Data Visualization and Browser Interface

The UCSC Genome Browser interface is often praised for its simplicity and user-friendliness, making it highly accessible for new users [35]. Its configuration system allows for extensive customization of the visual display, such as showing non-coding genes, splice variants, and pseudogenes on the GENCODE knownGene track [30]. The tooltips and color-coding in various tracks, such as the Developmental Disorders Gene2Phenotype (DDG2P) track which uses colors to indicate the strength of gene-disease associations, enable rapid visual assessment of data [30].

Ensembl's browser also provides powerful visualization capabilities but can present a steeper learning curve due to the density of information and integrated nature of its features [35]. Its strength lies in displaying its own rich gene models and comparative genomics data, such as cross-species alignments, directly within the genomic context.

Data Access and Mining Tools

Both platforms provide powerful tool suites for data extraction, but with different implementations.

- UCSC Table Browser and REST API: The UCSC Table Browser is a cornerstone tool for downloading and filtering data from any of the thousands of annotation tracks available in the browser [36]. It allows researchers to perform complex queries based on genomic regions, specific genes, or track attributes. For programmatic access, the UCSC REST API returns data in JSON format, facilitating integration into custom analysis pipelines [36].

- Ensembl BioMart and REST API: Ensembl's primary data-mining tool is BioMart, a highly sophisticated system that enables users to retrieve, filter, and export complex datasets across multiple species and data types [32] [33]. This is particularly powerful for projects requiring multi-factorial queries. Similar to UCSC, Ensembl also provides a comprehensive REST API for programmatic data retrieval [37].

Specialized Analytical Tools

Each browser offers unique tools for specific genomic analyses.

- UCSC Tools: The platform provides several specialized utilities, including BLAT for ultra-fast sequence alignment, the In-Silico PCR tool for verifying primer pairs, LiftOver for converting coordinates between different genome assemblies, and the Variant Annotation Integrator for annotating genomic variants with functional predictions [36].

- Ensembl Tools: A key analytical tool provided by Ensembl is the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP), which analyzes genomic variants and predicts their functional consequences on genes, transcripts, and protein sequence, as well as regulatory regions [33].

Table 2: Key Tools for Data Retrieval and Analysis

| Tool Type | UCSC Genome Browser | Ensembl |

|---|---|---|

| Data Mining | Table Browser [36] | BioMart [32] [33] |

| Sequence Alignment | BLAT [36] | BLAST/BLAT [33] |

| Variant Analysis | Variant Annotation Integrator [36] | Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) [33] |

| Programmatic Access | REST API (returns JSON) [36] | REST API & Perl API [37] |

| Assembly Conversion | LiftOver [36] | Assembly Converter |

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

The choice of genome browser and its underlying annotations has a profound, quantifiable impact on downstream genomic analyses, particularly in transcriptomics.

Impact of Annotation on RNA-Seq Analysis

A critical study evaluating Ensembl, RefSeq, and UCSC annotations in the context of RNA-seq read mapping and gene quantification demonstrated that the choice of gene model dramatically affects results [34]. The following protocol and findings illustrate this impact:

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Gene Model Impact on RNA-Seq Quantification

- Data Acquisition: Obtain a high-quality RNA-Seq dataset, such as the 16-tissue dataset from the Human Body Map 2.0 Project used in the study [34].

- Two-Stage Mapping:

- Stage 1 (Read Filtering): Filter out all RNA-Seq reads that are not covered by the gene model being evaluated (e.g., Ensembl, UCSC). This ensures a fair assessment limited to annotated regions.

- Stage 2 (Comparative Mapping): Map the remaining reads to the reference genome both with and without the assistance of the gene model (which provides splice junction information) [34].

- Quantification and Comparison: Quantify gene expression levels using each gene model's annotation. Compare the expression levels for common genes across the different models to assess consistency.

Key Findings from the Protocol:

- Junction Read Mapping: The study found that for a 75 bp RNA-Seq dataset, only 53% of junction reads (which span exon-exon boundaries) were mapped to the exact same genomic location when different gene models were used. Approximately 30% of junction reads failed to align without the assistance of a gene model [34].

- Gene Quantification Discrepancies: When comparing gene quantification results between RefSeq and Ensembl annotations, only 16.3% of genes had identical expression counts. Notably, for 9.3% of genes (2,038 genes), the relative expression levels differed by 50% or more [34]. This level of discrepancy can significantly alter biological interpretations.

Workflow for Clinical Variant Interpretation

For researchers and clinicians investigating the pathogenic potential of genetic variants, a structured workflow using both browsers is highly effective.

Diagram: A workflow for clinical variant interpretation integrating UCSC Genome Browser and Ensembl tools.

- Initial Visualization in UCSC Genome Browser: Input the variant coordinates into the UCSC Browser. Visualize its location relative to high-quality gene annotations like the GENCODE knownGene track [30] and examine its overlap with regulatory tracks.

- Literature and Functional Context in UCSC:

- Check the VarChat track to see a summary of available scientific literature on the variant [31].

- Consult the AlphaMissense track to assess a predicted pathogenicity score [31].

- View the DDG2P track to see if the gene has established gene-disease associations and the associated allelic requirements [30].

- Consequence Prediction with Ensembl VEP: Use the variant coordinates as input for the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP). This tool will provide a detailed prediction of the variant's effect on all overlapping transcripts (e.g., missense, stop-gain, splice site disruption) [33].

- Evidence Integration: Synthesize the evidence from both platforms—visual context and literature from UCSC, and functional predictions from Ensembl—to form a holistic assessment of the variant's potential clinical significance.

The following table details key resources available on these platforms that are essential for functional genomics research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Genome Browsers

| Resource Name | Platform | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GENCODE knownGene | UCSC Genome Browser [30] | Default gene track providing high-quality manual/automated gene annotations; essential for defining gene models in RNA-Seq or variant interpretation. |

| AlphaMissense Track | UCSC Genome Browser [31] | AI-predicted pathogenicity scores for missense variants; serves as a primary filter for prioritizing variants in disease studies. |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | Ensembl [33] | Annotates and predicts the functional consequences of known and novel variants; critical for determining a variant's molecular impact. |

| CoLoRSdb Tracks | UCSC Genome Browser [30] | Catalog of genetic variation from long-read sequencing; provides improved sensitivity in repetitive regions for structural variant analysis. |

| Developmental Disorders G2P Track | UCSC Genome Browser [30] | Curated list of genes associated with severe developmental disorders, including validity and mode of inheritance; used for diagnostic filtering. |

| BioMart | Ensembl [33] | Data-mining tool to export complex, customized datasets (e.g., all transcripts for a gene list); enables bulk downstream analysis. |

| SpliceAI Wildtype Tracks | UCSC Genome Browser [30] | Shows predicted splice acceptor/donor sites on the reference genome; useful for evaluating new transcript models and potential exon boundaries. |

The UCSC Genome Browser and Ensembl are both powerful, yet distinct, pillars of the functional genomics infrastructure. The UCSC Genome Browser excels as a centralized visualization platform and data aggregator, offering unparalleled access to a diverse universe of annotation tracks and user-friendly tools for rapid exploration and data retrieval. Its recent integration of AI-powered tracks like AlphaMissense and VarChat demonstrates its commitment to providing cutting-edge resources for variant interpretation. Ensembl's strength lies in its integrated, consistent, and comparative annotation system, supported by powerful data-mining tools like BioMart and analytical engines like the Variant Effect Predictor.

For researchers in drug development and clinical science, the choice is not necessarily mutually exclusive. A synergistic approach is often most effective: using the UCSC Genome Browser for initial data exploration and to gather diverse evidence from literature and functional predictions, and then leveraging Ensembl for deep, systematic annotation and consequence prediction. As the study on RNA-Seq quantification conclusively showed, the choice of genomic resource can dramatically alter analytical outcomes [34]. Therefore, a clear understanding of the capabilities, data sources, and inherent biases of each platform is not just an academic exercise—it is a fundamental requirement for robust and reproducible genomic science.

Applying Functional Genomics Databases in Disease Research and Target Discovery

Linking Genetic Variations to Disease Using dbSNP and GWAS Catalogs

The translation of raw genomic data into biologically and clinically meaningful insights is a cornerstone of modern precision medicine. This process, central to functional genomics, relies heavily on the use of specialized databases to link genetic variations to phenotypic outcomes and disease mechanisms. Two foundational resources in this endeavor are the Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP) and the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog. The dbSNP archives a vast catalogue of genetic variations, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), small insertions and deletions, and provides population-specific frequency data [38] [39]. In parallel, the GWAS Catalog provides a systematically curated collection of genotype-phenotype associations discovered through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [40] [41]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the integration of these resources enables the transition from variant identification to functional interpretation, a critical step for elucidating disease biology and identifying novel therapeutic targets [42]. This guide provides a technical overview of the methodologies and best practices for leveraging these databases to connect genetic variation to human disease.

A successful variant-to-disease analysis depends on a clear understanding of the available core resources and their interrelationships. The following table summarizes the key databases and their primary functions.

Table 1: Key Genomic Databases for Variant-Disease Linking

| Database Name | Primary Function and Scope | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| dbSNP [38] [39] | A central repository for small-scale genetic variations, including SNPs and indels. | Provides submitted variant data, allele frequencies, genomic context, and functional consequence predictions. |

| GWAS Catalog [40] [41] | A curated resource of published genotype-phenotype associations from GWAS. | Contains associations, p-values, effect sizes, odds ratios, and mapped genes for reported variants. |

| ClinVar [38] | Archives relationships between human variation and phenotypic evidence. | Links variants to asserted clinical significance (e.g., pathogenic, benign) for inherited conditions. |

| dbGaP [38] [39] | An archive and distribution center for genotype-phenotype interaction studies. | Houses individual-level genotype and phenotype data from studies, requiring controlled access. |

| Alzheimer’s Disease Variant Portal (ADVP) [43] | A disease-specific portal harmonizing AD genetic associations from GWAS. | Demonstrates a specialized resource curating genetic findings for a complex disease, integrating annotations. |