Functional Genomics Screening Strategies in 2025: A Comparative Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern functional genomics screening strategies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Functional Genomics Screening Strategies in 2025: A Comparative Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern functional genomics screening strategies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, core methodologies including CRISPR-based screens and NGS, practical troubleshooting for data and computational challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current market trends, technological innovations, and real-world applications, this guide serves as a strategic resource for selecting and optimizing screening approaches to accelerate target identification and therapeutic development.

The Functional Genomics Landscape: Core Principles and Market Drivers

Functional genomics is a field dedicated to bridging the critical gap between genetic information and biological meaning. It leverages data from genomics, transcriptomics, and other biological modalities to understand how genetic variation influences protein functions, gene regulation, and complex cellular processes [1]. The central challenge it addresses is that while generating genomic data has become routine, a substantial proportion of human genes—approximately 30% of the estimated 20,000 protein-coding genes—remain poorly characterized [1]. Furthermore, clinical sequencing often identifies genetic variants of uncertain significance, and genome-wide association studies have revealed that most disease-associated variants lie in non-coding regulatory regions, the functions of which are largely unknown [1]. Functional genomics addresses these gaps by systematically perturbing genes or regulatory elements and analyzing the resulting phenotypic changes, thereby moving beyond mere association to establish causal links between genotypes and phenotypes [2] [1].

Comparison of Functional Genomics Screening Platforms

The evolution of functional genomics has been driven by advances in technologies for targeted gene perturbation. Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of the primary screening platforms used for systematic functional interrogation.

Table 1: Comparison of Functional Genomics Screening Platforms

| Platform | Mechanism of Action | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Typical Screening Format | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNAi (siRNA/shRNA) | Introduces dsRNA to trigger mRNA degradation and gene silencing [3]. | Well-established; viral vectors enable sustained silencing [3]. | High off-target effects; incomplete knockdown leads to false negatives [2]. | Arrayed or Pooled | Initial, lower-cost loss-of-function studies. |

| CRISPR-KO (Cas9) | Creates double-strand breaks, leading to frameshift indels and gene knockouts [2]. | High precision and efficiency; fewer off-target effects than RNAi; enables complete gene disruption [2]. | Limited to coding genes with reading frames; DNA break toxicity can confound results [2]. | Primarily Pooled | Gold standard for definitive loss-of-function screens. |

| CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB) | Uses catalytically dead Cas9 fused to a repressor domain to block transcription [2]. | No DNA breaks; targets non-coding RNAs and enhancers; reversible knockdown [2]. | Knockdown is often incomplete (reversible). | Pooled | Essential gene studies; non-coding element screens. |

| CRISPRa (dCas9-Activator) | Uses dCas9 fused to activator domains (e.g., VP64, VPR) to enhance gene transcription [2]. | Enables gain-of-function studies without cDNA overexpression. | Potential for non-physiological overexpression effects. | Pooled | Gain-of-function and gene suppressor screens. |

Benchmarking Screening Performance: CRISPR Library Efficiency

A critical development in CRISPR-based functional genomics is the optimization of guide RNA (gRNA) libraries. Benchmark studies have systematically compared the performance of different genome-wide libraries to enhance screening efficiency and cost-effectiveness [4].

Experimental Protocol for Library Benchmarking

A standard protocol for benchmarking gRNA libraries involves several key steps [4]:

- Library Design: A benchmark library is assembled by compiling gRNA sequences from multiple established libraries (e.g., Brunello, Yusa v3, Toronto v3) targeting a defined set of genes. This set typically includes essential genes (categorized as early, mid, and late) and non-essential genes, as determined from reference databases [4].

- Cell Line Selection & Transduction: The pooled gRNA library is cloned into a viral vector and transduced at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) into Cas9-expressing cell lines (e.g., HCT116, HT-29, A549) to ensure most cells receive only one gRNA.

- Phenotypic Selection: Transduced cells are cultured for multiple population doublings. Cells carrying gRNAs targeting essential genes are depleted over time, while those with non-targeting controls (NTCs) persist.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Genomic DNA is harvested at baseline and subsequent time points. The integrated gRNAs are amplified via PCR and quantified by next-generation sequencing. Depletion or enrichment of each gRNA is calculated as a log-fold change relative to the initial time point. Gene-level fitness effects are often modeled using algorithms like Chronos, which analyzes the time-series data [4].

Key Benchmarking Findings

Recent studies have yielded crucial insights for selecting and designing CRISPR libraries, summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of CRISPR gRNA Library Designs

| Library Design | Guides per Gene | Performance in Essentiality Screens | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Libraries (e.g., Yusa v3) | ~6 | Strong depletion of essential genes [4]. | Robust data; well-validated. | Higher cost and sequencing burden [4]. |

| Small, Score-Optimized (e.g., Vienna-single) | 3 (selected by VBC score) | Equal or superior depletion compared to larger libraries [4]. | Cost-effective; enables screens in complex models (e.g., organoids, in vivo) [4]. | Relies on accurate on-target efficiency prediction. |

| Dual-Targeting Libraries | 2 pairs per gene | Stronger depletion of essentials than single-targeting [4]. | Can create definitive deletions; may compensate for less efficient guides. | May trigger a heightened DNA damage response, even in non-essential genes [4]. |

The evidence indicates that smaller, pruned libraries (e.g., 3 guides per gene) selected using advanced on-target efficacy scores like the Vienna Bioactivity CRISPR (VBC) score can perform as well as or better than larger legacy libraries [4]. This finding is critical for increasing the feasibility of screens in complex and physiologically relevant models where material is limited.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful functional genomics screen relies on a suite of key reagents and tools. The following table details the essential components of a modern CRISPR-based screening workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered enzyme that induces a double-strand break at a specific DNA site [2]. | Different variants (e.g., SpCas9, HiFi Cas9) offer trade-offs between efficiency, specificity, and PAM requirements [5]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Library | A pooled collection of synthetic RNAs that direct Cas9 to target genomic loci; the core of the screen [2] [6]. | Design (genome-wide vs. focused), size, and gRNA selection algorithm are critical for performance and cost [4]. |

| Viral Delivery Vector | Typically a lentivirus used to deliver the gRNA library stably into the target cell population [3] [2]. | Ensuring high titer and low MOI is essential for uniform library representation and avoiding multiple gRNAs per cell. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cell Line | A stable cell line that constitutively expresses the Cas9 nuclease, enabling efficient gene editing upon gRNA delivery. | Cell line choice must reflect the biological context of the research question (e.g., cancer type, relevant tissue origin). |

| Selection Antibiotics | Used to select for cells that have successfully integrated the viral vector carrying the gRNA library (e.g., puromycin) [2]. | Optimization of selection timing and concentration is required to achieve high representation of transduced cells. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | Essential for the readout of pooled screens by quantifying gRNA abundance before and after selection [2]. | Requires sufficient sequencing depth to cover the entire library with high representation. |

Experimental Workflow of a Pooled CRISPR Screen

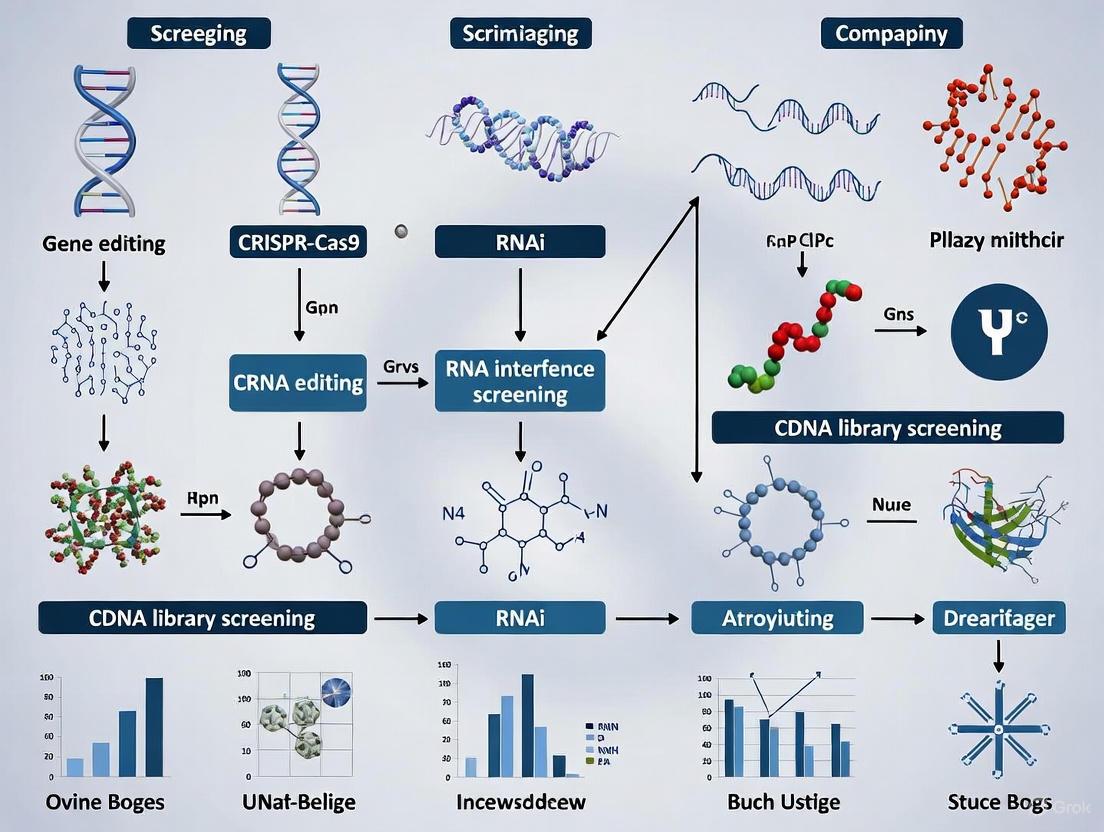

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a pooled CRISPR knockout screen, from library design to hit identification.

Diagram: Pooled CRISPR Screen Workflow

Functional genomics has been revolutionized by CRISPR-based tools, which provide an unprecedented ability to systematically map gene function. The ongoing refinement of these tools—including the development of smaller, more efficient gRNA libraries, base editors for single-nucleotide changes, and prime editors for precise insertions and deletions—continues to enhance the precision and scope of functional genomics studies [2] [1]. Furthermore, the integration of single-cell readouts (e.g., Perturb-seq) and the application of screens in more physiologically relevant models like organoids and in vivo systems are paving the way for discoveries that are more directly translatable to human biology and disease treatment [2] [1]. As these technologies mature, they will undoubtedly accelerate the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets, solidifying functional genomics as a cornerstone of modern biological research and drug discovery.

Article Contents

- Industry Overview and Growth Drivers: Examines the multi-billion dollar market size and key forces propelling the industry forward.

- Comparative Analysis of Screening Technologies: Objectively compares CRISPR, RNAi, and cDNA overexpression technologies using structured data.

- Experimental Protocols in Functional Genomics: Provides detailed methodologies for gain-of-function and loss-of-function screens.

- Essential Research Reagent Solutions: Lists key materials and tools used in functional genomics experiments.

The global genetic testing market, a core sector encompassing functional genomics, is anticipated to reach USD 24.45 billion in 2025, with forecasts projecting a climb to over USD 65 billion by 2034 [7]. This remarkable growth is fueled by sustained research and development (R&D) investment, which drives innovation in sequencing technologies, data analysis, and screening applications. The expansion is not uniform globally; while North America currently holds just over half of the global market share, the Asia-Pacific region is the fastest-growing market, expected to register a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 25.7% from 2024 to 2032 [7].

Several key trends and enablers are contributing to this growth trajectory:

- Technological Advancements: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become the standard, and long-read sequencing is gaining traction for its ability to identify structural changes and hard-to-detect variants. Furthermore, AI and machine learning are now integral, helping to comb through massive genomic datasets to find non-obvious patterns and links between genes and outcomes [7].

- Shift to Preventive Health: Genetic testing is evolving from a reactive tool to a central component of predictive health. By 2025, it is becoming routine for health systems to use genomic data to predict an individual's likelihood of certain health risks, allowing for early interventions [7].

- Rising Chronic Illness and Awareness: Increased rates of chronic illness and growing awareness of personalized medicine across all age groups are fueling demand for genetic insights [7].

Table: Key Market Growth Metrics

| Metric | Value | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Projected Market Value (2025) | USD 24.45 Billion | 2025 Forecast [7] |

| Projected Market Value (2034) | > USD 65 Billion | 2034 Forecast [7] |

| Fastest Growing Region | Asia-Pacific | 2024-2032 [7] |

| CAGR of Fastest Growing Region | 25.7% | 2024-2032 [7] |

Comparative Analysis of Screening Technologies

Functional genomics relies on several core technologies to systematically probe gene function. The main strategies involve loss-of-function (knockdown/knockout) and gain-of-function (overexpression) experiments [8] [9]. The choice of technology depends on the research question, desired duration of effect, and experimental scale.

CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized the field due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and adaptability [5]. Unlike older methods, CRISPR uses a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a specific DNA sequence, making design rapid and straightforward. It is highly scalable and ideal for genome-wide pooled screens to identify essential genes and novel drug targets [5] [10]. However, it can be subject to off-target effects, though improved Cas enzymes are mitigating this risk [5].

RNA interference (RNAi), including siRNA and shRNA, is a well-established method for gene silencing. siRNAs are typically used for transient knockdown in arrayed screens, while shRNAs, especially when delivered via lentiviral vectors, allow for long-term, stable gene silencing [8] [3]. A key consideration is that RNAi acts at the mRNA level and may not achieve complete knockout, potentially leading to incomplete silencing and off-target effects [8].

cDNA Overexpression is used for gain-of-function screens. This approach involves introducing cDNA libraries into cells to ectopically express proteins and observe the resulting phenotypes [3]. While powerful for identifying genes that overcome a biological block or activate a pathway, it can lead to non-physiological artifacts due to supraphysiological expression levels [3].

Table: Comparison of Functional Genomics Screening Technologies

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | RNAi (siRNA/shRNA) | cDNA Overexpression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | DNA-level knockout or knock-in via double-strand breaks and cellular repair [5]. | mRNA-level knockdown via degradation of target transcript [3]. | Protein-level overexpression of a gene of interest [3]. |

| Primary Application | Loss-of-function (KO), gain-of-function (CRISPRa), and functional genomics screens [5] [9]. | Transient (siRNA) or stable (shRNA) loss-of-function knockdown screens [8] [3]. | Gain-of-function screens to identify genes that induce a phenotype [3]. |

| Ease of Use & Scalability | Simple gRNA design; highly scalable for high-throughput and pooled screens [5] [10]. | Design is more complex than CRISPR; scalable, but arrayed screens require robotics [8]. | Library construction can be complex; scalable with viral delivery systems [3]. |

| Key Advantages | High efficiency, cost-effective, multiplexing capability, permanent genetic change [5]. | Well-established, effective transient knockdown (siRNA), stable silencing (shRNA) [8]. | Directly identifies genes that confer phenotypes or overcome pathway blocks [3]. |

| Key Limitations/Challenges | Potential for off-target effects; immune responses in therapeutic contexts [5]. | Incomplete knockdown; off-target effects due to miRNA-like activity [3]. | Non-physiological, artifact-prone results from overexpression [3]. |

Experimental Protocols in Functional Genomics

To ensure reproducible and reliable results, standardized experimental protocols are critical. The following sections detail common workflows for gain-of-function and loss-of-function screens.

Gain-of-Function Screening with cDNA Libraries

This protocol identifies genes that, when overexpressed, induce a desired phenotype (e.g., drug resistance, viral resistance) [3].

- Library Construction: Clone a cDNA library (e.g., from a relevant tissue or cell line) into a lentiviral or retroviral expression vector. These systems allow for efficient infection and stable integration into a wide variety of cell types, including non-dividing cells [3].

- Cell Transduction: Transduce the target cell population with the viral cDNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive only one viral integrant.

- Phenotypic Selection: Apply a selective pressure or assay for the desired phenotype. For example, infect transduced cells with a virus (e.g., HIV-1) if the goal is to find host factors that restrict viral replication [3].

- Selection and Cloning: Isolate cells exhibiting the phenotype (e.g., via FACS sorting for GFP-negative cells if the virus carries a GFP reporter). Expand these resistant cells as clonal populations [3].

- Hit Identification: Recover the integrated cDNA from resistant clones through PCR amplification and sequencing. The identified gene is the "hit" responsible for the phenotype [3].

Loss-of-Function Screening with Pooled CRISPR Libraries

This protocol identifies genes whose knockout results in a change in cell fitness or survival under selective pressure [10].

- Library Selection & Virus Production: Choose a genome-wide or focused pooled CRISPR library consisting of a complex mix of lentiviral vectors, each encoding a specific gRNA. Produce high-titer lentivirus from this library [8] [10].

- Cell Transduction & Selection: Transduce a large population of cells (e.g., Cas9-expressing cells) with the lentiviral library at a low MOI to ensure each cell receives only one gRNA. Apply puromycin or another selective agent to eliminate untransduced cells [10].

- Selection Pressure: Split the cell population and apply a specific selective pressure (e.g., a drug treatment) to the experimental group, while maintaining a control group without selection.

- Genomic DNA Extraction & Sequencing: After a period of growth under selection, extract genomic DNA from both control and experimental cells. Amplify the integrated gRNA sequences by PCR and subject them to next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Hit Confirmation: Identify gRNAs that are significantly enriched or depleted in the experimental group compared to the control. Genes targeted by these gRNAs are considered hits. These hits must be validated using orthogonal methods, such as individual gRNAs or alternative assays [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for selecting a functional genomics screening strategy.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful functional genomics screen depends on high-quality, well-validated reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics Screening

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Screening | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Designed for RNAi-mediated gene knockdown. siRNA for transient effects, shRNA for stable silencing [8] [3]. | shRNA libraries are often delivered via lentivirus for stable integration. Multiple siRNAs per gene are needed to confirm on-target effects [8]. |

| CRISPR gRNA Libraries | Designed for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout. Guide RNAs direct the Cas nuclease to specific genomic loci [5] [10]. | Available as pooled or arrayed formats. Minimal genome-wide libraries are now available, offering high efficiency with 50% fewer gRNAs [10]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | A delivery system for stably introducing genetic material (e.g., shRNA, gRNA, cDNA) into a wide variety of cells, including primary and non-dividing cells [8] [3]. | Enables long-term, integrated expression. Production of arrayed lentiviral libraries is costly and technically challenging [8]. |

| cDNA/ORF Libraries | Collections of open reading frames (ORFs) for gain-of-function screens. Used to ectopically express proteins in cells [3]. | Can be delivered via plasmid or viral vectors. Viral delivery (e.g., lentivirus) expands the range of susceptible cell types [3]. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscopy platforms that collect quantitative, multi-parametric data on cellular phenotypes (e.g., morphology, protein localization) [3]. | Provides rich, contextual data beyond simple viability or reporter assays. Essential for complex phenotypic readouts [3]. |

The convergence of rising global chronic disease prevalence and advancements in genomic technologies is fundamentally reshaping the pharmaceutical and biotechnology research landscape. For researchers and drug development professionals, this shift necessitates a critical evaluation of functional genomics screening strategies. These strategies are pivotal for identifying novel therapeutic targets in an era increasingly defined by precision medicine. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key methodologies, focusing on their experimental protocols, data output, and applicability in bridging population health trends with targeted drug discovery. The rising burden of chronic conditions, which now affect a majority of the US adult population, underscores the urgent need for such innovative approaches [11] [12].

The Driving Forces: Data and Market Trends

The Chronic Disease Burden

Recent data reveals a significant and growing prevalence of chronic diseases, which is a primary driver for the personalized medicine sector. The table below summarizes key U.S. statistics from 2023.

Table 1: Prevalence of Chronic Conditions among U.S. Adults (2023) [11] [12]

| Condition or Category | Prevalence (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ≥1 Chronic condition | 76.4 | Represents ~194 million adults |

| ≥2 Chronic conditions (MCC) | 51.4 | Represents ~130 million adults |

| High cholesterol | 35.3 | |

| High blood pressure | 34.5 | |

| Obesity | 32.7 | |

| Depression | 20.2 | |

| Diabetes | 12.1 | |

| Cancer | 8.0 | |

| Heart disease | 6.5 |

This burden is not static. From 2013 to 2023, the prevalence of at least one chronic condition increased from 72.3% to 76.4%, with the most notable rises observed among young adults (aged 18-34), for whom the rate increased by 7.0 percentage points [11]. This trend indicates a pressing need for earlier therapeutic interventions and more effective, targeted treatments.

The Personalized Medicine Market

In response to these health challenges, the personalized medicine market is experiencing substantial growth, fueled by technological innovation and increased investment.

Table 2: Personalized Medicine Market Overview [13] [14] [15]

| Region / Segment | Market Size / Share | Growth (CAGR) | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market | $654.46B (2025) → $1,315.43B (2034) | 8.10% | 2025-2034 |

| U.S. Market | $169.56B (2024) → $307.04B (2033) | 6.82% | 2025-2033 |

| North America | 45% share (2024) | - | - |

| Personalized Genomics Segment | $12.57B (2025) → $52B (2034) | 17.2% | 2025-2034 |

| Oncology Application | 41.96% share (2024) | - | - |

Key drivers include advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS), rising demand for customized treatments, and supportive government policies. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is further enhancing precision in diagnostics and treatment selection [13] [14].

Comparative Analysis of Functional Genomics Screening Strategies

A core challenge in oncology drug discovery is identifying tumor vulnerabilities and linking them to specific patient populations. Functional genomics screens, such as the landmark Project Achilles which screened 216 cancer cell lines against 11,000 genes, provide rich data for this purpose [16]. The analytical strategy applied to this data is critical. The following table compares two primary approaches.

Table 3: Comparison of Functional Genomics Screening Strategies [16]

| Feature | Pre-defined Group Analysis | Outlier Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Compares groups of cell lines pre-defined by known genetic contexts (e.g., KRAS mutant vs. wild-type). | Identifies genes with exceptional sensitivity in subsets of cell lines without prior biological assumptions. |

| Hypothesis Basis | Hypothesis-driven; requires a priori knowledge. | Data-driven; agnostic to prior knowledge. |

| Key Advantage | Directly tests established biological mechanisms. | Unbiased discovery of novel or complex genetic contexts and vulnerabilities. |

| Key Limitation | Limited by completeness of biological knowledge; impractical to query all contexts. | Requires subsequent validation to elucidate the biological mechanism causing the outlier response. |

| Example Discovery | ARID1B as a vulnerability in ARID1A-mutant cancers [16]. | Identification of context-dependent essential genes like tumor suppressors with potential oncogenic roles [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Outlier Analysis in Functional Genomics

Outlier analysis serves as a powerful, data-driven complement to pre-defined group comparisons. The following protocol is adapted from a study analyzing the Achilles (v2.4.3) ATARiS dataset [16].

This protocol aims to identify genes whose knockdown confers exceptional sensitivity to a subset of cell lines, indicating a potential therapeutic vulnerability. It employs three complementary statistical methods to ensure robust identification of outlier patterns.

Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics Screening [16]

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Lentiviral shRNA Library | Delivers sequence-specific short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) for stable gene knockdown in target cell lines. |

| Cancer Cell Line Panel | A diverse set of cell lines (e.g., 216 in Achilles) representing genetic heterogeneity across tumor types. |

| ATARiS Algorithm | Computational method to analyze shRNA data and generate gene-level dependency scores by filtering out off-target effects. |

| PACK (Profile Analysis using Clustering and Kurtosis) Software | Model-based pattern recognition algorithm to discover bimodal distribution in gene dependency profiles. |

| OS (Outlier Sum) Statistic Algorithm | Numerical method to identify genes with values outside a variability-based limit in a subset of samples. |

| GAP (Gap Analysis Procedure) Algorithm | A non-parametric method to identify genes where a group of sensitive lines is separated by a major "gap" from the bulk population. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Acquisition and Pre-processing:

- Obtain gene-level dependency scores (e.g., ATARiS scores) from a genome-scale shRNA screen (e.g., Project Achilles) for a large panel of cancer cell lines.

- Format the data into a matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent cell lines.

Application of Outlier Detection Algorithms (Run in parallel):

- PACK Analysis:

- For each gene, determine the number of clusters in its dependency profile across cell lines.

- Select genes with a bimodal distribution.

- Compute the kurtosis of the two clusters. Focus on genes with positive kurtosis, where one cluster is a small "outlier" subgroup.

- Filter for genes where the outlier subgroup has increased vulnerability (lower ATARiS score).

- Outlier Sum (OS) Analysis:

- For each gene, calculate the OS statistic, which sums the values of cell lines falling outside a pre-determined range based on data variability.

- Assess the statistical significance (FDR ≤ 0.05) of the OS statistic using a permutation-based approach to estimate false discovery rates.

- Gap Analysis Procedure (GAP):

- For each gene, rank cell lines by their dependency score.

- Calculate the "gap-to-range ratio" (Q statistic) to identify genes where a subgroup of sensitive cell lines is separated by a large gap from the rest of the population.

- Determine statistical significance (FDR ≤ 0.05) via permutation testing.

- PACK Analysis:

Data Integration and Filtering:

- Take the union of outlier genes identified by the PACK, OS, and GAP methods.

- Apply a minimum group size filter (e.g., at least 5 cell lines in the outlier group) to avoid spurious hits from single outliers.

- The resulting gene list represents high-confidence vulnerabilities with an exceptional responder pattern.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for the outlier analysis protocol.

Government Initiatives as a Key Driver

Government agencies are actively creating a supportive ecosystem for precision medicine, directly impacting research directions and resources. A prominent example is the ARPA-H THRIVE (Treating Hereditary Rare Diseases with In Vivo Precision Genetic Medicines) program [17].

- Goal: Develop integrated platform technologies to accelerate the creation of affordable, scalable precision genetic medicines (PGMs) for both rare and common diseases.

- Focus Areas: The program seeks proposals across three modules: 1) platform development for rapid PGM iteration, 2) investigational medicine, and 3) real-world viability pilots and scaling. It specifically focuses on in vivo approaches and excludes gene supplementation therapy [17].

- Research Impact: Such initiatives provide critical funding and a regulatory framework that encourages the development of single-intervention, curative treatments, aligning closely with the goals of identifying high-value targets through functional genomics.

Furthermore, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has developed frameworks to expedite the approval of targeted therapies and companion diagnostics, creating a clearer pathway for discoveries from the lab to reach patients [13].

For the research community, the interplay between chronic disease prevalence, market growth in personalized medicine, and supportive government initiatives defines the current therapeutic development landscape. Within this context, the choice of functional genomics screening strategy is paramount. While pre-defined group analysis tests specific hypotheses, outlier analysis offers a powerful, unbiased strategy for novel target discovery. Its ability to pinpoint exceptional responders in genomic data is essential for realizing the goals of precision medicine—delivering the right treatment to the right patient at the right time. The ongoing growth in chronic diseases, particularly among younger populations, underscores the critical and timely nature of this research approach.

In functional genomics screening, the convergence of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), CRISPR-based gene editing, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) is creating a powerful, iterative cycle of discovery. This synergy is transforming how researchers decipher gene function, identify therapeutic targets, and understand disease mechanisms at an unprecedented scale and precision. The foundational relationship between these technologies is one of mutual reinforcement: CRISPR enables precise genetic perturbations, NGS measures the complex molecular outcomes, and AI models discern subtle, high-dimensional patterns from the resulting data, often leading to new, testable biological hypotheses.

The sections below provide a detailed comparison of their roles, supported by experimental data, protocols, and key research reagents.

Core Technologies and Their Synergistic Roles

The following table outlines the primary functions and contributions of each technology within the functional genomics workflow.

| Technology | Core Function in Functional Genomics | Key Input | Key Output | Impact on Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR | Programmable genetic perturbation | Guide RNA (gRNA) designs | Genetically modified cells or organisms; phenotype data | Enables systematic high-throughput screening by creating defined genetic variants [5] [18] |

| NGS | Multiplexed molecular phenotyping | DNA/RNA libraries from CRISPR-edited samples | Genome-wide sequence, expression, and epigenetic data | Provides high-dimensional, unbiased readout of screening outcomes [19] |

| AI/ML | Predictive modeling and pattern recognition | NGS data and experimental parameters | Optimized gRNAs; novel editor designs; functional predictions | Accelerates design and interpretation, uncovering patterns beyond human discernment [20] [21] [22] |

Quantitative Comparison of Functional Genomics Screening Strategies

Different screening strategies leverage these technologies in distinct ways, each with advantages and limitations. The table below compares their performance based on key metrics.

| Screening Strategy | Typical Scale (Number of Perturbations) | Primary Readout | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Representative AI Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) | Genome-wide (~20,000 gRNAs) | DNA sequencing (indel detection); cell viability | Directly interrogates gene essentiality; well-established | Off-target effects; confounding false positives in viability screens [5] | DeepCRISPR for off-target prediction [19] |

| CRISPR Activation/Inhibition (e.g., CRISPRa/i) | Targeted or genome-wide | RNA sequencing (transcriptomic changes) | Reveals gene overexpression effects; can study non-coding regions | Effects can be indirect and influenced by epigenetic context | R-CRISPR for gRNA design [19] |

| Single-Cell CRISPR Screens (Perturb-seq) | Hundreds to thousands | Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Resolves cell-to-cell heterogeneity; links perturbation to full transcriptome | High cost per cell; complex computational analysis | ChromFound for scATAC-seq data analysis [23] |

| AI-Generated Editor Screening (e.g., OpenCRISPR-1) | Custom (novel protein designs) | NGS-based activity & specificity profiling | Access to editors with novel properties (e.g., smaller size, higher fidelity) | Requires extensive functional validation in relevant models [20] | Protein language models (e.g., ProGen2) for de novo design [20] |

Experimental Protocols for an Integrated Workflow

A typical integrated functional genomics screen involves a cyclical process of design, execution, and analysis.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput CRISPR Knockout Screen with NGS Readout

- Step 1: gRNA Library Design and Cloning

- Methodology: A library of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) is designed to target every protein-coding gene in the genome (typically 3-5 gRNAs per gene). AI tools like DeepCRISPR or CRISPR-GPT are used to select gRNAs with maximal on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects [19] [22]. The designed oligonucleotides are synthesized in a pooled format and cloned into a lentiviral Cas9 vector.

- Step 2: Delivery and Selection

- Methodology: The pooled lentiviral library is transduced into a cell line expressing Cas9 at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one gRNA. Cells are selected with puromycin for several days to generate a representation of the library [18].

- Step 3: Phenotypic Selection and NGS Preparation

- Methodology: The selected cell population is divided into experimental groups (e.g., drug-treated vs. control) and passaged for 2-3 weeks. Genomic DNA is harvested at the start and end of the experiment. The gRNA sequences are amplified via PCR and prepared for NGS to track their relative abundance over time [18].

- Step 4: NGS and AI-Powered Data Analysis

- Methodology: The prepared libraries are sequenced on an NGS platform (e.g., Illumina). The read counts for each gRNA are compared between the initial and final time points. Depleted gRNAs in the final population indicate essential genes under the experimental condition. AI and machine learning models (e.g., MAGeCK) are used to statistically rank gene essentiality, correct for screen-level biases, and identify significant hits [19].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Functional Validation with AI-Designed Editors

- Step 1: AI-Driven Editor Design

- Methodology: As demonstrated with OpenCRISPR-1, a large language model (e.g., ProGen2) is fine-tuned on a massive dataset of natural CRISPR-Cas sequences (e.g., the CRISPR–Cas Atlas). The model is then prompted or conditioned to generate millions of novel, diverse protein sequences that are predicted to be functional nucleases [20].

- Step 2: In Vitro Activity and Specificity Screening

- Methodology: The genes for the AI-generated editors are synthesized and tested in human cells. Their editing activity and specificity are measured using NGS-based assays (e.g., GUIDE-seq or CRISPResso2) to quantify on-target efficiency and profile off-target sites [20] [19]. Top candidates are selected based on performance relative to benchmarks like SpCas9.

- Step 3: In Vivo Delivery and Efficacy Assessment

- Methodology: The lead candidate (e.g., OpenCRISPR-1) is packaged into delivery vehicles such as Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) and administered in vivo. For example, in a mouse model of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), the editor is delivered systemically via intravenous injection. LNPs naturally accumulate in the liver, where the disease-associated TTR protein is primarily produced [24] [25].

- Step 4: NGS-Based Molecular Validation

Visualizing the Integrated Workflow and AI Architecture

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow and the underlying AI model architecture that powers modern functional genomics.

Integrated Functional Genomics Screening Workflow

AI Model Architectures in Genomics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these integrated strategies relies on a suite of key reagents and tools.

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Product/Model |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Induces double-strand breaks in DNA for gene knockout. | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) [18] |

| Base Editor | Enables precise single-nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks. | ABE8e, BE4max [21] |

| AI-Designed Editor | Provides novel editing proteins with optimized properties (size, fidelity). | OpenCRISPR-1 [20] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery vehicle for CRISPR components; targets liver. | Acuitas Therapeutics LNP [24] [25] |

| Lentiviral Vector | Efficient delivery of gRNA libraries for high-throughput screens. | pLentiCRISPR v2 [18] |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares DNA or RNA samples for high-throughput sequencing. | Illumina Nextera XT [19] |

| AI Design Assistant | AI agent for experimental design, gRNA selection, and troubleshooting. | CRISPR-GPT [22] |

| Variant Caller | Uses deep learning to identify genetic variants from NGS data with high accuracy. | DeepVariant [19] |

| Off-Target Analysis Tool | Detects and quantifies genome-wide off-target editing events from NGS data. | CRISPResso2 [19] |

| Single-Cell Foundation Model | Analyzes single-cell chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq) data. | ChromFound [23] |

Functional genomics screening is a cornerstone of modern biological research and drug discovery, enabling the systematic identification of genes involved in specific biological pathways or disease states [26]. These screens employ forward genetics approaches, where researchers create genetic perturbations and observe resulting phenotypic changes to establish causal gene-phenotype relationships [26]. Over the past decade, the field has undergone significant technological evolution, moving from early models in yeast to RNA interference (RNAi) and now to CRISPR-based screening technologies [27].

The functional genomics market reflects this technological progression, with transcriptomics technologies—focused on studying the complete set of RNA transcripts—emerging as the dominant segment. Current market analysis indicates the global transcriptomics technologies market is poised to grow from USD 7.01 billion in 2024 to USD 12.79 billion by 2034, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.24% [28]. This growth is largely driven by the expanding applications of transcriptomics in drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and the development of personalized medicine [29] [28].

Table 1: Global Transcriptomics Technologies Market Overview

| Metric | 2024 Value | 2025 Value | 2034 Projected Value | CAGR (2025-2034) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | USD 7.01 Billion | USD 7.44 Billion | USD 12.79 Billion | 6.24% |

Technology Performance Comparison

The current functional genomics screening ecosystem primarily utilizes four main technological approaches, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal use cases.

Comparative Analysis of Screening Technologies

Table 2: Functional Genomics Screening Technologies Comparison

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Limitations | Genome Coverage | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Screening [27] | PCR-based gene disruption in S. cerevisiae or S. pombe | Well-annotated genome; high-throughput; conserved genes | Limited human homology; tolerates higher toxicant levels | All non-essential yeast genes | Toxicogenomics; conserved pathway analysis |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) [27] [30] | Post-transcriptional gene silencing via mRNA degradation | Applicable to many cell types; extensive library availability | Incomplete knockdown; significant off-target effects | Genome-wide at RNA level | Hypomorphic phenotypes; partial knockdown studies |

| CRISPR-Cas9 [27] [26] | Precise DNA cleavage creating knockout mutations | High specificity; permanent knockout; fewer off-target effects | Requires PAM sequence; potential DNA damage response | Genome-wide at DNA level | Essential gene identification; drug target discovery |

| Haploid Cell Screening [27] | Insertional mutagenesis in KBM7 or HAP1 cells | Extends yeast approach to human context | Limited to specific cell types; genomic integration bias | All human genes except chromosome 8 | Bacterial toxin mechanisms; viral host factors |

CRISPR vs. RNAi: Direct Performance Comparison

A systematic comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 and RNAi screens in the human K562 leukemic cell line provides crucial experimental evidence for technology selection [30]. Both technologies demonstrated high performance in detecting essential genes (AUC > 0.90), with similar precision at a 1% false positive rate (>60% of gold standard essential genes recovered) [30].

However, significant differences emerged in downstream analysis:

- CRISPR screens identified approximately 4,500 genes with growth phenotypes

- RNAi screens identified approximately 3,100 genes with growth phenotypes

- Only ~1,200 genes were identified by both technologies [30]

This discrepancy suggests these technologies provide complementary biological information, with each method uniquely suited to interrogate different biological processes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pooled CRISPR Screening Workflow

The pooled CRISPR screening approach enables genome-wide functional interrogation in a single experiment [26]. The standard workflow consists of six key stages that ensure robust, interpretable results.

Detailed Protocol:

Library Design: Select sgRNAs targeting genes of interest. Current benchmarking studies indicate that libraries designed using Vienna Bioactivity CRISPR (VBC) scores outperform others, with the top 3 VBC guides per gene providing optimal efficiency [4]. Dual-targeting libraries (two sgRNAs per gene) show enhanced knockout efficiency but may trigger DNA damage response [4].

Viral Production: Package sgRNA plasmids into lentiviral particles. Proper titer determination is critical for achieving optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA [26].

Cell Transduction: Incubate target cells with lentiviral particles. Cas9-expressing cells are required; these can be pre-engineered or co-transduced [26].

Selection: Apply selective pressure (e.g., puromycin) for 1-2 weeks to eliminate non-transduced cells and ensure uniform library representation [26].

Phenotype Assay: Expose cells to experimental conditions (e.g., compound treatment, viability pressure). For pooled screens, this must be a binary assay that physically separates cells based on phenotype [26].

Sequencing & Analysis: Extract genomic DNA, amplify integrated sgRNAs, and perform next-generation sequencing. Computational tools like MAGeCK or Chronos analyze sgRNA enrichment/depletion to identify hit genes [4].

Transcriptomics Profiling via RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing has become the gold standard for transcriptome analysis, providing comprehensive gene expression quantification [29] [28]. The standard protocol involves:

Critical Steps and Parameters:

- Sample Collection: Snap-freeze tissues or stabilize cells in RNAlater. Extract total RNA using column-based methods [28].

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity number (RIN > 8 recommended) using bioanalyzer or similar systems [28].

- Library Preparation: Select mRNA via poly-A selection or remove ribosomal RNA via ribodepletion. Fragment RNA, synthesize cDNA, and add platform-specific adapters [29].

- Sequencing: Utilize Illumina platforms for high-throughput applications (≥30 million reads/sample for standard differential expression) [28].

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using STAR or HISAT2 aligners [31].

- Differential Expression: Employ statistical methods (DESeq2, edgeR) to identify significantly altered genes, followed by pathway enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) [31].

Market Analysis and Application Segmentation

Transcriptomics Technologies Market Share

The dominance of transcriptomics in the functional genomics landscape is evidenced by its substantial market share and diverse applications across multiple sectors.

Table 3: Transcriptomics Market Segmentation and Forecast (2024-2034)

| Segmentation Category | Dominant Segment | Market Share (2024) | Fastest-Growing Segment | Projected CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology [28] | Next-Generation Sequencing | Largest share in 2024 | Polymerase Chain Reaction | Significant |

| Application [29] [28] | Drug Discovery & Research | Largest share in 2024 | Clinical Diagnostics | Highest |

| End-User [29] [28] | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies | Largest share in 2024 | Academic & Government Institutes | Highest |

| Region [29] [28] | North America | Dominant position in 2024 | Asia Pacific | Fastest-growing |

Regional Market Distribution

North America currently dominates the transcriptomics technologies market, benefiting from extensive R&D investments, advanced healthcare infrastructure, and concentration of leading biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies [29] [28]. The Asia Pacific region is projected to be the fastest-growing market during the forecast period, driven by increasing numbers of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, rising healthcare expenditures, and growing research investments [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful functional genomics screens require carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table outlines critical components for establishing robust screening platforms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Genomics Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening Tools [26] [4] | Brunello, GeCKO v2, Vienna-single libraries | Genome-wide sgRNA collections for systematic gene knockout |

| CRISPR Enzymes [26] | S. pyogenes Cas9, HiFi Cas9, Cas12a | Nucleases for precise DNA cleavage; engineered variants reduce off-target effects |

| Delivery Systems [26] | Lentiviral particles, lipid nanoparticles | Enable efficient sgRNA delivery across diverse cell types |

| Sequencing Platforms [28] [31] | Illumina NovaSeq X, Oxford Nanopore | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing for readout and analysis |

| Cell Culture Models [27] | Immortalized lines, iPSCs, primary cells | Biologically relevant systems for phenotypic assessment |

| Analysis Software [28] [31] | MAGeCK, Chronos, DESeq2, DeepVariant | Computational tools for screen deconvolution and data interpretation |

The functional genomics field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies shaping its future trajectory:

Single-Cell and Spatial Technologies: Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics are revolutionizing resolution in transcriptomics, enabling researchers to dissect cellular heterogeneity and map gene expression within tissue architecture [28] [31]. These approaches are particularly valuable in cancer research for identifying resistant subclones and understanding tumor microenvironments [31].

Artificial Intelligence Integration: AI and machine learning are transforming genomic data analysis, with tools like DeepVariant improving variant calling accuracy and AI models enabling better prediction of therapeutic responses from transcriptomic data [28] [31]. The recent $12 million Series A investment in Biostate AI exemplifies the growing recognition of AI's potential in transcriptomics [28].

CRISPR Library Optimization: Ongoing refinement of CRISPR libraries focuses on improved efficiency and reduced size. Recent benchmarking demonstrates that smaller libraries (3 guides/gene) designed using principled criteria like VBC scores perform as well or better than larger libraries, reducing costs and increasing feasibility for complex models [4].

In conclusion, transcriptomics maintains its dominant position in the functional genomics landscape due to its dynamic nature, comprehensive profiling capabilities, and expanding applications in personalized medicine. While CRISPR-based screening has emerged as the preferred method for systematic gene perturbation due to its precision and reliability, the complementary use of multiple technologies provides the most robust approach for identifying and validating gene-disease relationships. As technologies continue to advance and integrate with artificial intelligence, functional genomics screening will play an increasingly pivotal role in accelerating drug discovery and enabling precision medicine approaches.

Core Screening Technologies: From CRISPR to NGS and Multi-Omics Integration

Functional genomics screening with CRISPR-Cas technology has revolutionized systematic gene function analysis, enabling researchers to decipher complex genetic relationships in health and disease. Three primary modalities have emerged as powerful tools in the geneticist's arsenal: CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko), CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa). Each approach offers distinct mechanisms and applications, from complete gene ablation to precise transcriptional control. CRISPRko utilizes the nuclease-active Cas9 to create double-strand breaks in DNA, resulting in permanent gene disruption through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair. This often produces small insertions or deletions (INDELs) that can cause frameshift mutations and premature stop codons, effectively abolishing gene function [32]. In contrast, CRISPRi employs a nuclease-dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional repressor domains like KRAB to block transcription without altering the DNA sequence, while CRISPRa uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators to enhance gene expression [33].

The choice between these modalities depends on the biological question, with CRISPRko providing complete loss-of-function, CRISPRi enabling reversible gene suppression, and CRISPRa facilitating gain-of-function studies. Understanding their relative performances, optimal applications, and technical requirements is essential for researchers designing functional genomics screens. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these technologies, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform screening strategies in biomedical research and drug development.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Applications

Molecular Mechanisms and Genetic Outcomes

The fundamental differences between CRISPR screening modalities stem from their distinct molecular mechanisms and resulting genetic outcomes. CRISPRko operates through DNA cleavage and repair, introducing permanent genetic changes. When a single sgRNA is used, Cas9-induced double-strand breaks are repaired via the error-prone NHEJ pathway, potentially resulting in small insertions or deletions (INDELs). If these INDELs are not multiples of three, they cause frameshift mutations that can lead to non-functional or truncated proteins. When two sgRNAs are employed, large genomic deletions can be achieved, effectively removing entire exons or functional domains [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying the function of specific protein domains without completely abolishing gene expression.

CRISPRi and CRISPRa, in contrast, provide reversible, epigenetic control of gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. CRISPRi functions through dCas9 fusion proteins that recruit repressive complexes to gene promoters. The most common approach fuses dCas9 to the KRAB (Krüppel-associated box) domain, which promotes heterochromatin formation and effectively silences transcription [33]. CRISPRa systems employ various strategies to recruit transcriptional activation machinery, including direct fusions to activator domains like VP64, protein scaffolds such as the SunTag system, and RNA scaffolds like the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) [33]. These systems enable precise control over endogenous gene expression levels, making them ideal for studying dose-dependent gene effects and for probing genes where complete knockout would be lethal.

Performance Benchmarks and Experimental Comparisons

Recent benchmarking studies have quantitatively compared the performance of different CRISPR screening modalities in various experimental contexts. The development of optimized libraries has significantly enhanced screening performance, with metrics like dAUC (delta area under the curve) providing standardized measures for comparing essential gene detection capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPRko Libraries in Negative Selection Screens

| Library Name | sgRNAs per Gene | dAUC Value | ROC-AUC Value | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunello [34] | 4 | 0.80 | 0.98 | Best overall performance by dAUC metric |

| TKOv3 [34] | 4 | 0.78 | 0.97 | Strong performance in haploid cell lines |

| Avana [34] | 4 | 0.72 | 0.95 | Balanced performance across cell types |

| GeCKOv2 [34] | 6 | 0.58 | 0.94 | Early genome-wide library |

| Yusa v3 [4] | 6 | 0.65 | 0.93 | Good performance with more guides |

In negative selection screens, the optimized CRISPRko library Brunello demonstrated superior performance in distinguishing essential and non-essential genes, achieving a dAUC of 0.80 in A375 melanoma cells, compared to 0.58 for GeCKOv2 [34]. This improvement represents a greater performance leap than the previous transition from RNAi to early CRISPRko libraries. For CRISPRi, the Dolcetto library has been shown to achieve comparable performance to CRISPRko in detecting essential genes, despite using fewer sgRNAs per gene [34].

Dual-targeting strategies, where two sgRNAs target the same gene, have shown enhanced depletion of essential genes compared to single-targeting approaches. However, this benefit comes with a potential cost, as dual-targeting guides also exhibit a fitness reduction even in non-essential genes, possibly due to increased DNA damage response from creating twice the number of double-strand breaks [4]. This suggests that dual-targeting libraries should be used with caution in screens where DNA damage response could confound results.

When comparing CRISPRko to alternative technologies like shRNA, recent analyses of 254 cell lines revealed that shRNA outperforms CRISPR in identifying lowly expressed essential genes, while both platforms perform well for highly expressed essential genes but with limited overlap between hits [35]. This suggests that a combination of both platforms may provide the most comprehensive coverage for highly expressed essential genes.

Experimental Design and Workflow

High-Throughput Screening Protocols

Successful CRISPR screening requires meticulous experimental design and execution. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for pooled CRISPR knockout screens:

Stage 1: Library Design and Selection

- Select an optimized sgRNA library based on experimental needs (e.g., Brunello for genome-wide knockout, MiniLib for compressed libraries)

- For gene-level screens, aim for 3-6 highly active sgRNAs per gene using prediction algorithms like VBC scores or Rule Set 3 [4]

- Include non-targeting control sgRNAs (minimum 1000) to establish baseline abundance distributions

- For dual-targeting approaches, design sgRNA pairs targeting the same gene with consideration of potential DNA damage response effects

Stage 2: Lentiviral Library Production and Transduction

- Clone the sgRNA library into appropriate lentiviral vectors (e.g., lentiGuide)

- Produce high-titer lentivirus using HEK293T or similar packaging cells

- Transduce target cells at a low MOI (∼0.3-0.5) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA

- Maintain minimum 500x coverage to ensure each sgRNA is represented in hundreds of cells

- Apply selection antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) for 3-7 days to remove uninfected cells

Stage 3: Screening Execution and Phenotypic Selection

- For dropout screens, passage cells for 2-3 weeks, maintaining minimum coverage throughout

- For chemical or genetic interaction screens, apply selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment) at appropriate concentrations

- Include untreated control populations cultured in parallel

- Harvest cells at multiple time points for time-series analyses

- Extract genomic DNA from minimum 500 cells per sgRNA to maintain representation

Stage 4: Sequencing and Data Analysis

- PCR-amplify integrated sgRNA cassettes from genomic DNA using barcoded primers

- Sequence amplified products on Illumina platforms to obtain sgRNA counts

- Calculate sgRNA depletion/enrichment using tools like MAGeCK or Chronos

- For gene-level analysis, aggregate scores across multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene

- Compare experimental conditions to identify significantly altered genes [4] [34]

Specialized Methodologies for CRISPRi/a Screens

CRISPRi and CRISPRa screens follow similar overall workflows but require specific modifications:

Cell Line Engineering

- Stably integrate dCas9-KRAB (for CRISPRi) or dCas9-activator (for CRISPRa) into target cells using lentiviral transduction or other methods

- Select stable pools or clones with consistent dCas9 fusion expression

- For inducible systems, validate tight control of dCas9 expression without leakiness

Library Design Considerations

- Design sgRNAs to target promoter regions proximal to transcription start sites

- For CRISPRa, consider systems with enhanced activation capabilities (e.g., SAM, SunTag) for stronger phenotypes

- Include multiple negative controls (non-targeting sgRNAs) and positive controls (sgRNAs targeting essential genes)

Screen Optimization

- For CRISPRi, determine optimal sgRNA positioning relative to TSS through pilot tests

- For CRISPRa, test multiple activation systems to identify the most effective for your cell type

- Establish appropriate screening duration—typically shorter than CRISPRko screens due to reversible nature of perturbation [33]

dot code for screening workflow

Diagram 1: High-throughput CRISPR screening workflow showing four major stages from library design to data analysis.

Research Reagents and Tools

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRko Libraries | Brunello, Avana, TKOv3, Yusa v3, Vienna | Complete gene knockout; varies in sgRNAs per gene and performance | Brunello shows highest dAUC (0.80); Vienna offers compressed design [4] [34] |

| CRISPRi Libraries | Dolcetto | Gene repression via dCas9-KRAB; targets promoters | Performs comparably to CRISPRko in essential gene detection [34] |

| CRISPRa Libraries | Calabrese, SAM | Gene activation via dCas9-activator fusions | Calabrese outperforms SAM in resistance gene identification [34] |

| Cas9 Variants | Wild-type SpCas9, HiFi Cas9 | DNA cleavage for knockout; high-fidelity versions reduce off-targets | HiFi Cas9 improves specificity with minimal efficiency loss [34] |

| dCas9 Effectors | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR, SunTag-dCas9 | Transcriptional repression/activation without DNA cleavage | KRAB provides strong repression; VPR and SunTag enhance activation [33] |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Introduce CRISPR components into cells | Lentiviral for stable integration; LNPs for transient delivery [25] |

| sgRNA Design Tools | CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR, FlashFry, GuideScan | Design and evaluate sgRNA efficiency and specificity | Varying computational performance; little consensus between tools [36] |

Computational Tools for Guide RNA Design

The selection of highly active, specific sgRNAs is crucial for successful CRISPR screens, and numerous computational tools have been developed for this purpose. A comprehensive benchmark of 18 design tools revealed wide variation in runtime performance, compute requirements, and guides generated [36]. Only five tools had computational performance that would allow analysis of an entire mammalian genome in reasonable time without exhausting computing resources. Tools also varied in their approach, with some using machine learning models trained on experimental data (e.g., CHOPCHOP, WU-CRISPR, sgRNAScorer2) while others employed procedural rules (e.g., Cas-Designer, CRISPOR) [36].

The most striking finding was the lack of consensus between tools, with different programs often recommending different sgRNAs for the same target. This suggests that improvements in guide design will likely require combining multiple approaches or developing new algorithms that integrate diverse prediction metrics. When designing sgRNAs for screening, researchers should consider using multiple tools and prioritizing sgRNAs with consistent high scores across different platforms.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Cell-Type-Specific Essentiality Mapping

Recent advances in CRISPR screening have enabled the mapping of genetic dependencies across diverse cellular contexts. A 2025 study used inducible CRISPRi to compare essentiality of mRNA translation machinery genes in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPS cells) and hiPS cell-derived neural and cardiac cells [37]. The screens revealed that while core components of the mRNA translation machinery were broadly essential, the consequences of perturbing translation-coupled quality control factors were highly cell-type dependent. Human stem cells critically depended on pathways that detect and rescue slow or stalled ribosomes, particularly the E3 ligase ZNF598 for resolving ribosome collisions at translation start sites [37].

This study demonstrated the power of comparative CRISPR screening across differentiation states, revealing how essential gene sets can be rewired during cellular specialization. The hiPS cells showed higher sensitivity to mRNA translation perturbations, with 200 of 262 (76%) genes scoring as essential compared to 176 (67%) in HEK293 cells, possibly linked to their exceptionally high global protein synthesis rates [37]. Such cell-type-specific dependencies represent potential therapeutic targets and highlight the importance of screening in relevant cellular contexts.

Therapeutic Target Discovery

CRISPR screens have proven invaluable for identifying new therapeutic targets, particularly in oncology. Genome-wide CRISPRko screens have identified novel dependencies in various cancer types, with hit validation rates significantly higher than previous RNAi-based approaches. For example, a CRISPR surface protein screen identified LRP4 as a key entry receptor for yellow fever virus, with soluble decoy receptors blocking infection in vitro and protecting mice in vivo [38]. Similarly, a CRISPR-Cas9 screen targeting chromatin regulators identified SETDB1 as essential for metastatic uveal melanoma cell survival, with SETDB1 inhibition curtailing tumor growth in vivo [38].

dot code for screening applications

Diagram 2: Diverse applications of CRISPR screening in biomedical research, ranging from basic biology to therapeutic development.

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mapping

CRISPR screens have dramatically advanced our understanding of how small molecules interact with their cellular targets. Drug-gene interaction screens can identify both the direct targets of compounds and mechanisms of resistance. In a benchmark study, Vienna-single and Vienna-dual libraries showed the strongest resistance log fold changes for validated resistance genes in osimertinib screens in lung adenocarcinoma cells, outperforming the Yusa v3 library [4]. Dual-targeting libraries consistently exhibited the highest effect sizes in both lethality and drug-gene interaction contexts, though with a potential fitness cost even in non-essential genes [4].

These chemical-genetic interaction maps provide insights for drug development, including biomarker identification for patient stratification and combination therapy strategies. For example, genetic screens have identified 19S proteasomal subunit levels as predictive biomarkers for multiple myeloma patient response to the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib, and revealed synergistic combinations such as PI3Kδ inhibitors with dexamethasone in B-cell precursor malignancies [33].

CRISPR screening technologies have matured significantly, with optimized libraries and protocols now enabling highly sensitive and specific genetic interrogation across diverse biological contexts. The choice between CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa depends on the specific research question, with CRISPRko providing the most complete loss-of-function, CRISPRi offering reversible suppression with fewer off-target effects, and CRISPRa enabling gain-of-function studies. Performance benchmarks demonstrate that well-designed libraries with fewer sgRNAs per gene can outperform larger libraries when guides are selected using principled criteria like VBC scores [4].

Future directions in CRISPR screening include the development of even more compact libraries without sacrificing performance, improved computational tools that combine multiple prediction algorithms for guide design, and the integration of single-cell readouts to capture complex phenotypes. As screening methods continue to evolve, they will further empower researchers to systematically decode gene function and identify novel therapeutic opportunities across human diseases.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research by enabling the simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, providing unprecedented capacity for analyzing genetic variations [39]. This transformative technology has fundamentally shifted approaches from single-gene analysis to comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP), allowing researchers to investigate entire genomes with remarkable speed and precision [40] [31]. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling represents a specific application of NGS that examines large panels of genes—sometimes hundreds—in a single assay, detecting diverse genomic alterations including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variants (SVs) [41] [42]. The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of genomics research, facilitating studies on rare genetic diseases, cancer genomics, microbiome analysis, infectious diseases, and population genetics [39].

The transition from conventional sequencing methods to NGS represents a paradigm shift in genomic analysis. Traditional Sanger sequencing, while highly accurate, processes only one DNA fragment at a time, making it laborious, costly, and time-consuming for large-scale analyses [40]. In contrast, NGS employs massively parallel sequencing architecture, enabling the concurrent analysis of millions of DNA fragments and providing markedly increased sequencing depth and sensitivity [40]. This comprehensive genomic coverage and higher capacity with sample multiplexing make NGS significantly more cost-effective for screening large numbers of samples and reliably detecting genes associated with disease formation and progression [40]. For complex diseases like cancer, which are driven by diverse and interacting genomic alterations, CGP provides clinically actionable molecular insights that guide diagnosis, prognostication, therapeutic selection, and monitoring of treatment response [40] [43].

NGS Technology Platforms and Their Comparative Performance

Major Sequencing Platforms

The NGS landscape is dominated by several major platforms, each with distinct technical approaches and performance characteristics. Illumina sequencing dominates second-generation NGS due to its exceptionally high throughput, low error rates (typically 0.1–0.6%), and attractive cost per base [40]. It uses sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry, enabling millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced in parallel on a flow cell [40]. Short reads (75–300 bp) provide high coverage and precision, making it suitable for genome resequencing, transcriptome profiling, and variant calling [40]. Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has introduced a distinctive approach with its nanopore sequencing, which involves directly reading single DNA molecules as they traverse a protein nanopore [40]. This method produces ultra-long reads (averaging 10,000–30,000 bp) and enables real-time sequencing, though with higher error rates that can spike up to 15% [39]. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) employs single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technology, which uses a specialized SMRT cell containing numerous small wells called zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [39]. Individual DNA molecules are immobilized within these wells, emitting light as the polymerase incorporates each nucleotide, allowing real-time measurement of nucleotide incorporation with read lengths averaging 10,000–25,000 bp [39].

Performance Comparison of NGS Platforms

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms and Their Performance Characteristics

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Error Rate | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 75-300 bp | 0.1-0.6% | Whole-genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, targeted sequencing | May contain errors from signal deconvolution in overcrowded flow cells [39] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sequencing | 10,000-30,000 bp | Up to 15% | Real-time sequencing, field sequencing, structural variant detection | Higher error rate compared to other platforms [39] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp | ~13% (random errors) | De novo genome assembly, full-length transcript sequencing, epigenetic modification detection | Higher cost compared to other platforms [39] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp | ~1% | Targeted sequencing, amplicon sequencing | Homopolymer sequences may lead to loss in signal strength [39] |

Table 2: NGS Platform Throughput and Data Output Comparison

| Platform | Throughput Capacity | Run Time | Maximum Output per Run | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Very high | 1-3 days | Up to 16 Tb | Large-scale population studies, whole-genome sequencing projects [31] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Variable (portable to high-throughput) | Minutes to days | Depends on device (2.8 Gb - 100+ Gb) | Real-time analysis, field applications, hybrid sequencing approaches [31] |

| PacBio Sequel II/Revio | High | 0.5-2 days | 15-360 Gb | Complete genome assembly, isoform sequencing, complex variant detection [39] |

The selection of an appropriate NGS platform represents a critical strategic decision that directly influences the feasibility and success of a research project. Second-generation platforms (exemplified by Illumina) and third-generation technologies (including PacBio and Oxford Nanopore) constitute a major advance in sequencing throughput, read length, and analytical resolution compared to earlier methods [40]. Short-read technologies like Illumina provide high accuracy for single-nucleotide variant detection, while long-read platforms from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore excel at resolving complex genomic regions, detecting structural variations, and performing de novo genome assemblies without reference bias [40] [39]. The choice between these technologies depends on the specific research questions, with many advanced genomics laboratories now implementing integrated approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of multiple platforms [40].

Experimental Design and Methodologies for CGP

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling Workflow

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Genomic Profiling Workflow

The CGP workflow begins with sample collection, which can involve either tissue biopsies or liquid biopsies (blood samples) [41]. Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for genomic testing of solid tumors as it allows analysis of both genomic changes and histological markers directly from the tumor [41]. However, liquid biopsy using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a minimally invasive alternative that expands access to patients for whom tissue biopsy may not be feasible and provides additional information about tumor heterogeneity [41]. For reliable results, specimens should contain sufficient tumor content, with most protocols recommending at least 25% tumor nuclei in the selected areas [43]. Following sample collection, nucleic acid extraction isolates DNA and RNA from the specimen, with quality control measures ensuring adequate quantity and purity for downstream applications [44].

Library preparation involves fragmenting the DNA, repairing ends, and ligating platform-specific adapters [44]. This critical step can introduce biases, particularly in PCR-dependent protocols where over-amplification can distort sequence heterogeneity and lead to loss of rare input molecules [44]. Target enrichment strategies, primarily hybridization-based capture or amplicon-based approaches, focus sequencing resources on genomic regions of interest [45]. Hybridization-based capture uses oligonucleotide probes to capture specific regions and offers flexibility in panel design, while amplicon approaches use PCR to amplify targets and generally require less input DNA [45]. The enriched libraries are then sequenced on an appropriate NGS platform, with the choice depending on the required coverage depth, read length, and application [40]. The resulting data undergoes bioinformatic analysis including alignment to a reference genome, variant calling, and annotation, culminating in interpretation and reporting of clinically actionable findings [43].

Key Quality Control Metrics and Performance Optimization

Table 3: Essential Quality Control Metrics for NGS Experiments

| Quality Metric | Definition | Optimal Range | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth of Coverage | Number of times a base is sequenced | Varies by application (typically 100-200X for somatic variants) | Higher coverage increases confidence in variant calling, especially for low-frequency variants [45] |

| On-target Rate | Percentage of reads mapping to target regions | >70% for hybrid capture panels | Indicates probe specificity and enrichment efficiency; low rates suggest suboptimal probe design or hybridization [45] |

| Duplicate Rate | Percentage of redundant reads | <20% for whole genomes; <30-50% for exomes | High rates indicate PCR over-amplification or insufficient library complexity; duplicates are removed during analysis [45] |

| GC Bias | Uneven coverage of GC-rich/AT-rich regions | Minimal deviation from expected distribution | High bias can lead to coverage gaps; introduced during library preparation or hybrid capture [45] |

| Fold-80 Base Penalty | Measure of coverage uniformity | Closer to 1 indicates better uniformity | Values >1.5 indicate uneven coverage, requiring more sequencing to cover all targets adequately [45] |

Accurate DNA quantification represents a critical foundational step in NGS library preparation. Traditional methods like UV spectrophotometry (Nanodrop) or fluorometry (Qubit) provide concentration measurements but lack the sensitivity needed for low-input samples [44]. Digital PCR technologies, including droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), have emerged as superior alternatives that enable absolute quantification of DNA molecules without requiring standard curves [44]. In one comprehensive comparison, ddPCR-based quantification demonstrated superior sensitivity and reliability compared to traditional methods, with a strong correlation between expected and observed measurements (R² = 0.9923, p < 0.0001) [44]. The adaptation of universal probe technologies to ddPCR platforms (ddPCR-Tail) further enhanced quantification accuracy by allowing precise measurement without prior knowledge of the intervening sequence between primers [44].