Functional Validation of Genetic Variants: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Concepts to Clinical Protocols

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for the functional validation of genetic variants.

Functional Validation of Genetic Variants: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Concepts to Clinical Protocols

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for the functional validation of genetic variants. It bridges the gap between variant discovery and clinical interpretation by exploring foundational principles, detailing cutting-edge methodological protocols like saturation genome editing and CRISPR-based assays, and addressing critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Furthermore, it establishes rigorous standards for assay validation and comparative analysis, essential for translating functional data into clinically actionable evidence. This guide synthesizes current best practices and emerging technologies to enhance accuracy in variant classification and accelerate the development of targeted therapies.

Understanding the Imperative: Why Functional Validation is Critical in Modern Genomics

The foundation of precision medicine relies on accurately interpreting the countless genetic variants uncovered through sequencing. At the heart of this challenge lies the Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS)—a genetic alteration whose effect on health is unknown. Current data reveals that more than 70% of all unique variants in the ClinVar database are classified as VUS, creating a substantial bottleneck in clinical decision-making [1]. The real-world impact of this uncertainty is significant: VUS findings can result in patient and provider misunderstanding, unnecessary clinical recommendations, follow-up testing, and procedures, despite being nominally nondiagnostic [1].

Recent evidence indicates that the burden of VUS is not evenly distributed. A 2025 study examining EHR-linked genetic data from 5,158 patients found that the number of reported VUS relative to pathogenic variants can vary by over 14-fold depending on the primary indication for testing and 3-fold depending on self-reported race, highlighting substantial disparities in how this uncertainty affects different patient populations [2] [1]. Furthermore, communication gaps plague the ecosystem, with at least 1.6% of variant classifications used in electronic health records for clinical care being outdated based on current ClinVar data, including numerous instances where testing labs updated classifications but never communicated these reclassifications to patients [2]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the methodologies and tools transforming VUS resolution, with particular focus on their applications in research and drug development contexts.

Methodological Frameworks for Variant Interpretation

Established Guidelines and Emerging Refinements

The 2015 ACMG/AMP guidelines established a standardized framework for variant classification using a five-tier system: pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign, and benign [3]. This evidence-based system evaluates variants across multiple criteria including population data, computational predictions, functional evidence, and segregation data [4]. However, the subjective application of these criteria, particularly for functional evidence, has led to interpretation discordance between laboratories [5].

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group has developed crucial refinements to address these limitations. Recent advancements include:

- Quantitative point-based system: Pathogenic evidence is scored as ≥10 (pathogenic), 6–9 (likely pathogenic), while benign evidence is scored as −1 to −6 (likely benign), and ≤−6 (benign) [6].

- Enhanced phenotype-specificity criteria (PP4): New ClinGen guidance provides a systematic method to assign higher evidence scores when patient phenotypes are highly specific to the gene of interest, particularly valuable for tumor suppressor genes with characteristic presentations [6].

- Standardized functional evidence application: Detailed recommendations for PS3/BS3 criterion application establish validation requirements for functional assays, including minimum control variants and experimental design standards [5].

A 2025 study demonstrated that applying these refined criteria to VUS in tumor suppressor genes resulted in 31.4% of previously uncertain variants being reclassified as likely pathogenic, with the highest reclassification rate in STK11 (88.9%) [6].

Computational Prediction Tools and Selection Frameworks

With over fifty computational pathogenicity predictors available, selecting appropriate tools for specific clinical or research applications presents a significant challenge [7]. These tools leverage machine learning algorithms to integrate biophysical, biochemical, and evolutionary factors, classifying missense variants as pathogenic or benign.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Selected Pathogenicity Prediction Tools

| Tool | Best Application Context | Coverage/Reject Rate | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| REVEL | General missense interpretation | 1.0 (no rejection) | Ensemble method combining multiple tools |

| CADD | Genome-wide variant prioritization | 1.0 (no rejection) | Integrative framework across variant types |

| PolyPhen2 | Missense variant filtering | 0.43-0.65 | Provides multiple algorithm modes (HDIV/HVAR) |

| SIFT | Conservation-based assessment | 0.43-0.65 | Evolutionary conservation focus |

| AlphaMissense | AI-driven assessment | Varies by implementation | Advanced neural network architecture |

A cost-based framework has been developed to address the tool selection challenge, encoding clinical scenarios using minimal parameters and treating predictors as rejection classifiers [7]. This approach naturally incorporates healthcare costs and clinical consequences, revealing that no single predictor is optimal for all scenarios and that considering rejection rates yields dramatically different perspectives on classifier performance [7].

Experimental Approaches for Functional Validation

Saturation Genome Editing for High-Throughput Functional Assessment

Saturation Genome Editing (SGE) represents a cutting-edge approach for functionally evaluating genetic variants at scale. This protocol employs CRISPR-Cas9 and homology-directed repair (HDR) to introduce exhaustive nucleotide modifications at specific genomic sites in multiplex, enabling functional analysis while preserving native genomic context [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Saturation Genome Editing

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function in Protocol | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| HAP1-A5 cells | Near-haploid human cell line | Enables easier genetic manipulation |

| CRISPR-Cas9 system | Precise genome editing | Introduces exhaustive nucleotide modifications |

| Variant libraries | Comprehensive variant testing | Designed to cover specific genomic regions |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) template | Template for precise editing | Ensures accurate variant introduction |

| Next-generation sequencing | Functional readout | Quantifies variant effects via deep sequencing |

The SGE workflow involves:

- Library design - creating variant libraries, single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), and oligonucleotide primers for PCR

- Sample preparation - preparing HAP1-A5 cells before the SGE screen

- Cellular screening - introducing variant libraries and selecting edited cells

- NGS library preparation - preparing sequencing libraries to quantify variant effects [8]

This approach has been successfully applied to clarify pathogenicity of germline and somatic variation in multiple genes including DDX3X, BAP1, and RAD51C, providing functional data at unprecedented scale [8].

Standardizing Functional Evidence Application

The ClinGen SVI Working Group has established a four-step provisional framework for evaluating functional evidence:

- Define the disease mechanism - establishing the molecular basis of disease for the specific gene

- Evaluate applicability of general assay classes - determining which types of functional assays are appropriate

- Evaluate validity of specific assay instances - assessing the technical validation of particular implementations

- Apply evidence to variant interpretation - determining the appropriate evidence strength based on validation [5]

Critical considerations for functional assay validation include:

- Control requirements: A minimum of 11 total pathogenic and benign variant controls are required to reach moderate-level evidence in the absence of rigorous statistical analysis [5].

- Physiologic context: Assays should reflect the relevant biological context, with patient-derived materials generally preferred for assessing organismal phenotypes [5].

- Molecular consequence: The variant context must be carefully considered, with CRISPR-introduced variants in normal genomic contexts generally providing more reliable data than artificial overexpression systems [5].

Comparative Analysis of Variant Interpretation Workflows

Integrated Approaches in Cancer Genomics

Recent research demonstrates the power of integrating multiple interpretation methodologies. A 2025 study on Colombian colorectal cancer patients combined next-generation sequencing with artificial intelligence methods to identify pathogenic and likely pathogenic germline variants [9]. This approach utilized:

- ACMG/AMP classification following established guidelines

- BoostDM artificial intelligence for identifying oncodriver germline variants

- Comparison with AlphaMissense pathogenicity predictions, achieving AUC values of 0.788 for the entire BoostDM dataset and 0.803 for genes within their panel

- Functional validation of intronic mutations using minigene assays, revealing aberrant transcripts potentially linked to disease etiology [9]

This integrated methodology identified 12% of patients as carrying pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants, while BoostDM identified oncodriver variants in 65% of cases, demonstrating how complementary approaches enhance detection beyond conventional methods [9].

For rare diseases, comprehensive database utilization is essential. Key resources include:

- ClinVar: Public archive of relationships between variants and phenotypes, though significant interpretation discrepancies exist between submitters [2] [10]

- gnomAD: Population frequency database critical for assessing variant rarity [10]

- Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO): Standardized vocabulary for phenotypic abnormalities, containing over 13,000 terms and 156,000 annotations to hereditary diseases [10]

- Mondo Disease Ontology: Unified ontology for rare diseases integrating multiple source vocabularies [10]

The re-analysis of exome data after 1-3 years with updated databases has been shown to increase diagnostic yields by over 10%, highlighting the importance of periodic reevaluation [10].

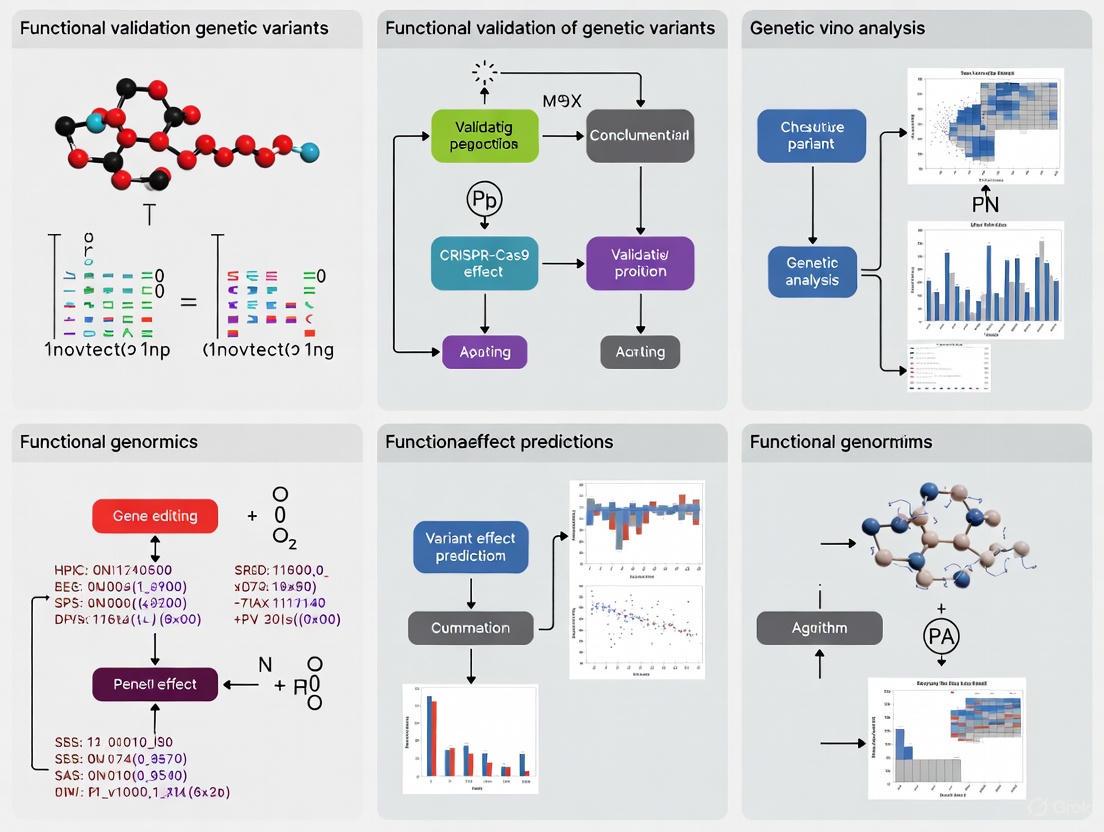

Visualization of Variant Interpretation Workflows

Comprehensive Variant Interpretation Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for resolving VUS, incorporating computational, clinical, and functional evidence:

Saturation Genome Editing Workflow

The SGE process for high-throughput functional evaluation involves the following specific steps:

The challenge of VUS interpretation requires a multifaceted approach combining evolving guidelines, computational tools, and functional validations. Disparities in VUS reporting and outdated classifications in clinical systems underscore the need for automated reevaluation processes and better communication channels between testing laboratories, clinicians, and patients [2] [1].

The most promising developments include:

- Refined classification criteria that leverage phenotype specificity and quantitative evidence scoring

- High-throughput functional methods like saturation genome editing that can systematically assess variant effects

- Integrated computational/experimental approaches that combine AI prediction with functional validation

- Standardized functional evidence frameworks that ensure consistent application across laboratories

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances enable more accurate variant interpretation, potentially accelerating therapeutic development and clinical trial stratification. As these methodologies continue to mature, they promise to transform the variant interpretation landscape, converting today's unknowns into tomorrow's actionable insights.

Functional validation of genetic variants represents a critical component in the interpretation of genomic data, bridging the gap between in silico predictions and clinical actionable findings. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) variant interpretation guidelines established the PS3 (pathogenic strong) and BS3 (benign strong) evidence codes for "well-established" functional assays that demonstrate abnormal or normal gene/protein function, respectively. However, the original framework provided limited guidance on how functional evidence should be evaluated, leading to significant interpretation discordance among clinical laboratories. This comparison guide examines the evolution of PS3/BS3 application criteria, evaluates current methodological approaches, and provides a structured framework for implementing functional evidence in variant classification protocols.

The PS3/BS3 Framework: Evolution and Standardization

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Refinements

Recognizing the need for more standardized approaches, the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Working Group developed detailed recommendations for applying PS3/BS3 criteria, creating a more structured pathway for functional assay assessment [5] [11]. This refinement process addressed a critical gap in the original ACMG/AMP guidelines, which did not specify how to determine whether a functional assay is sufficiently "well-established" for clinical variant interpretation [12].

The SVI Working Group established a four-step provisional framework for determining appropriate evidence strength:

- Define the disease mechanism and expected impact of variants on protein function

- Evaluate the applicability of general classes of assays used in the field

- Evaluate the validity of specific instances of assays

- Apply evidence to individual variant interpretation [5] [11] [13]

A key advancement was the quantification of evidence strength based on assay validation metrics. The working group determined that a minimum of 11 total pathogenic and benign variant controls are required to reach moderate-level evidence in the absence of rigorous statistical analysis [5] [14] [11]. This quantitative approach significantly improved the standardization of functional evidence application across different laboratories and gene-specific expert panels.

Points to Consider in Assay Validation

The ClinGen recommendations highlight several critical factors for evaluating functional assays:

Physiologic Context: The ClinGen recommendations advise that functional evidence from patient-derived material best reflects the organismal phenotype but suggests this evidence may be better used for phenotype-related evidence codes (PP4) rather than functional evidence (PS3/BS3) in many circumstances [5] [12].

Assay Robustness: For model organism data, the recommendations advocate for a nuanced approach where strength of evidence should be adjusted based on the rigor and reproducibility of the overall data [5].

Technical Validation: Validation, reproducibility, and robustness data that assess the analytical performance of the assay are essential factors, with CLIA-approved laboratory-developed tests generally providing more reliable metrics [12].

Quantitative Framework for Evidence Strength

Table 1: Evidence Strength Classification Based on Control Variants

| Evidence Strength | Minimum Control Variants Required | Odds of Pathogenicity | ACMG/AMP Code Equivalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting | 5-7 total controls | ~2.08:1 | PP1/BP4 |

| Moderate | 11 total controls | ~4.33:1 | PM2/BP2 |

| Strong | 18 total controls | ~18.7:1 | PP5/BP6 |

| Very Strong | >25 total controls with statistical analysis | >350:1 | PVS1 |

The classification system above derives from Bayesian analysis of theoretical assay performance, providing a mathematical foundation for evidence strength assignment [5] [12]. This quantitative approach represents a significant advancement over the original subjective assessment of what constitutes a "well-established" functional assay.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Validation

Case Study: KCNH2 Functional Patch-Clamp Assay

A robust functional patch-clamp assay for KCNH2 variants demonstrates the practical application of PS3/BS3 criteria [15]. This protocol employs:

- A curated set of 30 benign and 30 pathogenic missense variants to establish normal and abnormal function ranges

- Quantification of function reduction using Z-scores, representing standard deviations from the mean normalized current density of benign variant controls

- A Z-score threshold of -2 (corresponding to 55% wild-type function) for defining abnormal loss of function

- Progressive evidence strength with more extreme Z-scores receiving stronger pathogenicity support [15]

This approach successfully correlated functional data with clinical manifestations, demonstrating that the level of function assessed through the assay correlated with Schwartz score (a clinical diagnostic probability metric) and QTc interval length in Long QT Syndrome patients [15].

Emerging Technologies: Single-Cell DNA-RNA Sequencing

Recent advances in functional genomics have introduced novel approaches for variant characterization. Single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) enables simultaneous profiling of up to 480 genomic DNA loci and genes in thousands of single cells, allowing accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated gene expression changes [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Functional Assay Methodologies

| Methodology | Throughput | Key Applications | Physiological Relevance | Technical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology | Low | Ion channel function, kinetic properties | High (direct functional measurement) | Low throughput, technical complexity |

| Saturation Genome Editing | High | Multiplex variant functional assessment | Medium (endogenous context) | Requires specialized editing tools |

| SDR-seq | Medium-High | Coding/noncoding variants with expression | High (endogenous context, single-cell) | Computational complexity, cost |

| Patient-Derived Assays | Variable | Direct phenotype correlation | Very High (native physiological context) | Limited availability, confounding factors |

The SDR-seq protocol involves several key steps [16]:

- Cell Preparation: Dissociation into single-cell suspension followed by fixation and permeabilization

- In Situ Reverse Transcription: Using custom poly(dT) primers with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and barcodes

- Droplet-Based Partitioning: Loading onto microfluidics platform with cell lysis and protease treatment

- Multiplex PCR Amplification: Simultaneous amplification of gDNA and RNA targets within droplets

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Separate optimized library preparation for gDNA and RNA targets

This methodology enables confident linking of precise genotypes to gene expression in their endogenous context, overcoming limitations of previous technologies that suffered from high allelic dropout rates (>96%) [16].

Visualization of Functional Validation Workflows

PS3/BS3 Evaluation Framework

SDR-seq Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Validation Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Fixation Reagents (PFA, Glyoxal) | Preserve cellular structure and nucleic acids | SDR-seq protocol; glyoxal shows superior RNA target detection | PFA causes cross-linking; glyoxal preserves RNA quality [16] |

| Custom Poly(dT) Primers with UMIs | Reverse transcription with unique molecular identifiers | SDR-seq for quantifying mRNA molecules | Reduces amplification bias; enables digital counting [16] |

| Multiplex PCR Panels | Simultaneous amplification of multiple targets | Targeted gDNA and RNA sequencing | Requires careful primer design; panel size affects detection efficiency [16] |

| Barcoding Beads | Single-cell indexing in droplet-based systems | SDR-seq cell barcoding | Enables multiplexing; critical for single-cell resolution [16] |

| Variant Control Sets | Reference standards for assay validation | KCNH2 patch-clamp assay (30 benign/30 pathogenic variants) | Must represent diverse variant types; determines evidence strength [15] |

| Patch-Clamp Solutions | Ionic conditions for electrophysiology | KCNH2 channel function assessment | Must mimic physiological conditions; critical for reproducibility [15] |

The evolution of PS3/BS3 criteria application represents a significant advancement in functional genomics, moving from subjective assessments to quantitative, evidence-based frameworks. The standardized approaches developed by the ClinGen SVI Working Group provide a critical foundation for consistent variant interpretation across laboratories and disease contexts. Emerging technologies like SDR-seq and saturation genome editing offer powerful new approaches for functional characterization at scale, potentially expanding the repertoire of "well-established" assays available to clinical laboratories. As these methodologies continue to evolve, the integration of robust functional evidence will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between variant discovery and clinical application, ultimately enhancing patient care through more accurate genetic diagnosis.

The systematic interpretation of genetic variation represents a cornerstone of modern genomic medicine. For researchers and drug development professionals, moving beyond mere variant identification to a deep functional understanding is critical for elucidating disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of established methodologies for assessing the impact of genetic variants on three fundamental biological processes: protein function, RNA splicing, and gene regulation. Each approach generates distinct yet complementary data, and selecting the appropriate assessment strategy depends on the specific biological question, available resources, and desired throughput. The following sections objectively compare experimental protocols, their applications, and limitations, providing a framework for designing comprehensive functional validation pipelines.

Assessing Impact on Protein Function

Variants within coding regions can alter protein function through multiple mechanisms, including changes to catalytic activity, structural stability, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular localization. The experimental assessment of these effects employs diverse biochemical, cellular, and computational structural approaches.

Key Experimental Approaches and Data

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Methods for Assessing Protein Function Impact

| Method Category | Key Measurable Parameters | Typical Outputs | Evidence Strength for Pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Kinetics | Catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM), substrate affinity (KM), maximum velocity (Vmax) | Michaelis-Menten curves, kinetic parameters | High (Direct functional measure) |

| Protein-Protein Interaction Assays | Binding affinity, complex formation, dissociation constants | Yeast two-hybrid, co-immunoprecipitation, FRET/BRET | Medium to High (Context-dependent) |

| Protein Abundance & Localization | Steady-state protein levels, aggregation, nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, membrane trafficking | Western blot, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry | Medium (Can indicate instability/mislocalization) |

| Structural Analysis | Thermodynamic stability, folding defects, conformational changes | Thermal shift assays, X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, CD spectroscopy | High (Mechanistic insight) |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Micro-Western Array for Protein Quantification

The Micro-Western Array (MWA) provides a high-throughput, reproducible method for quantifying protein levels and modifications across many samples, enabling the detection of protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Pelleted cells (e.g., lymphoblastoid cell lines) are lysed in SDS-containing buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Samples are boiled, sonicated, and concentrated to standardize protein concentrations [17].

- Antibody Screening: A primary antibody library is validated for specificity. Antibodies are selected if they display a single predominant band of the predicted size with a signal-to-noise ratio ≥3 [17].

- Array Printing & Processing: Automated piezoelectric printing spots multiple technical and biological replicates of each sample onto nitrocellulose membranes. Serial dilutions of pooled lysates are included to ensure antibody signal linearity [17].

- Blotting & Detection: Proteins are resolved by horizontal semi-dry electrophoresis, transferred, and probed with validated primary and fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. Fluorescence is quantified using a scanner like the LI-COR Odyssey [17].

- Data Analysis: Raw integrated intensities are background-subtracted and log2-quantile normalized. Protein levels are analyzed relative to genetic variation to identify pQTLs. Notably, studies have shown that while up to two-thirds of cis mRNA expression QTLs (eQTLs) are also pQTLs, many pQTLs are not associated with mRNA expression, suggesting protein-specific regulatory mechanisms [17].

Conceptual Framework for Functional Effects

A systematic framework categorizes the functional effects of protein variants into four primary classes [18]:

- Abundance: Effects on gene dosage, protein expression, localization, or degradation.

- Activity: Alterations in enzymatic kinetics, allosteric regulation, or specific activity.

- Specificity: Changes in substrate promiscuity or the emergence of moonlighting functions.

- Affinity: Impacts on binding constants for substrates, cofactors, or interaction partners.

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Analysis

Table 2: Key Reagents for Protein Functional Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SDS Lysis Buffer with Inhibitors | Complete protein denaturation and inactivation of proteases/phosphatases | Protein extraction for Western Blots, MWAs |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Specific recognition and binding to target protein epitopes | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry |

| IR800/Alexa Fluor-conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Fluorescent detection of primary antibodies | Quantitative protein detection on LI-COR and other imaging systems |

| Protein Molecular Weight Marker | Accurate sizing of resolved protein bands | Gel electrophoresis |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Preservation of protein integrity and modification states during extraction | All protein handling steps post-cell lysis |

Figure 1: A framework for assessing the impact of genetic variants on protein function, linking functional categories to experimental methods.

Assessing Impact on RNA Splicing

Genetic variants can disrupt the precise process of pre-mRNA splicing by altering canonical splice sites, creating cryptic splice sites, or disrupting splicing regulatory elements. These disruptions can lead to non-productive transcripts targeted for degradation or altered protein isoforms.

Key Experimental Approaches and Data

Table 3: Comparison of Methods for Assessing Splicing Impact

| Method | Splicing Phenotype Measured | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq (Steady-State) | Exon inclusion levels (PSI), novel junctions, intron retention | Genome-wide, detects known and novel events | Underestimates unproductive splicing due to NMD |

| sQTL Mapping | Statistical association between genotype and splicing phenotype | Unbiased discovery across population | Requires large sample sizes; identifies association not causation |

| Nascent RNA-Seq (naRNA-Seq) | Splicing outcomes before cytoplasmic decay | Captures unproductive splicing prior to NMD | Experimentally complex; specialized protocols |

| Allelic Imbalance Splicing Analysis | Allele-specific splicing ratios from heterozygous SNVs | Controls for trans-acting factors; works in single individuals | Limited to genes with heterozygous variants |

| Mini-Gene Splicing Reporters | Splicing efficiency of specific exonic/intronic sequences | Direct causal testing; high-throughput | May lack full genomic context |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: LeafCutter for Splicing QTL (sQTL) Discovery

LeafCutter is a computational method that identifies genetic variants affecting splicing from RNA-seq data by quantifying variation in intron splicing, avoiding the need for pre-defined transcript annotations.

Methodology:

- Data Input: RNA-seq data (preferably from nascent RNA or after NMD inhibition to capture unproductive splicing) is aligned to the reference genome [19] [20].

- Intron Clustering: All mapped splice junction reads are grouped into "intron clusters" representing alternatively spliced regions. The tool focuses on reads spanning splice junctions to infer splicing patterns [19].

- Intron Usage Quantification: For each cluster, the usage of each intron is calculated, generating a matrix of intron usage ratios for each sample [19].

- Association Testing: The genotypes of samples are tested for association with the intron usage ratios. A significant association indicates a genetic variant that modulates splicing (sQTL) [19].

- Data Interpretation: sQTLs identified by LeafCutter are major contributors to complex traits. Studies show they are largely independent of eQTLs, with ~74% having little to no effect on overall gene expression levels, yet the majority (89%) affect the predicted coding sequence, potentially altering protein function [19]. Global analyses using nascent RNA-seq reveal that unproductive splicing is pervasive, affecting ~2.3% of splicing events and leading to NMD, accounting for at least 9% of post-transcriptional gene expression variance [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for Splicing Analysis

Table 4: Key Reagents for Splicing Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nascent RNA Capture Reagents (e.g., 4sU) | Metabolic labeling of newly transcribed RNA | Nascent RNA-seq (naRNA-seq) to capture pre-degradation transcripts |

| NMD Inhibition Reagents (shRNA/siRNA) | Knockdown of UPF1, SMG6, SMG7 | Stabilizing unproductive NMD-targeted transcripts for detection |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | RT-PCR analysis of splice isoforms |

| Splicing Reporter Vectors | Mini-gene constructs for candidate variant testing | Functional validation of splice-disruptive variants |

| PolyA+ & PolyA- RNA Selection Kits | Fractionation of RNA by polyadenylation status | Compartment-specific RNA-seq (nuclear vs. cytosolic) |

Figure 2: Pathways through which genetic variants disrupt normal RNA splicing, leading to productive or unproductive transcript outcomes.

Assessing Impact on Gene Regulation

Non-coding genetic variants can influence gene expression by altering transcriptional mechanisms, primarily through changes to cis-regulatory elements (CREs) such as enhancers and promoters. Assessing this impact requires measuring molecular phenotypes that reflect the activity of these regulatory sequences.

Key Experimental Approaches and Data

Table 5: Comparison of Methods for Assessing Gene Regulation Impact

| Method | Regulatory Phenotype Measured | Throughput | Functional Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression QTL (eQTL) Mapping | Steady-state mRNA levels associated with genetic variation | High (Population-scale) | Identifies statistical association; does not prove causality |

| Chromatin QTL (caQTL/hQTL) Mapping | Chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) or histone modification (ChIP-seq) association | Medium | Pinpoints functional regulatory elements; links variant to chromatin state |

| Transcription Rate Assays (4sU-seq) | Newly synthesized RNA via metabolic labeling | Medium | Direct measure of transcriptional output, deconfounds decay |

| Transcription Factor Binding Assays (ChIP-seq) | In vivo protein-DNA binding landscape | Low | Direct identification of TF binding sites and disruption |

| Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRA) | Regulatory activity of thousands of sequenced oligos | High | Direct, high-throughput functional testing of variants |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Integrated QTL Mapping from Transcription to Protein

This multi-layered QTL mapping approach dissects the flow of genetic effects through successive stages of gene regulation, from chromatin to proteins.

Methodology:

- Multi-Omic Data Collection: Generate molecular data from a population of individuals (e.g., lymphoblastoid cell lines). Key datasets include [19]:

- Chromatin Activity: H3K27ac, H3K4me3 ChIP-seq for active enhancers and promoters.

- Transcription Rates: 4sU-seq, which uses a pulse of 4-thiouridine to label and capture newly transcribed RNA.

- Steady-State RNA: RNA-seq for mature mRNA levels.

- Protein Levels: Mass spectrometry or antibody-based arrays (e.g., RPPA, MWA).

- Uniform QTL Mapping: Process all molecular phenotypes with a uniform computational pipeline to identify significant variant-trait associations (QTLs) for each layer [19].

- QTL Sharing Analysis: Quantify the sharing of QTLs across regulatory stages. Studies show that ~65% of eQTLs have primary effects on chromatin, while the remaining ~35% are enriched within gene bodies and may affect post-transcriptional processes [19].

- Effect Size Correlation: Analyze the correlation of genetic effect sizes across phenotypes. Effect sizes are highly correlated from transcription (4sU-seq) through protein levels, suggesting a percolation of genetic effects through the regulatory cascade [19].

- Data Interpretation: A Bayesian model estimates that 73% of QTLs affecting transcription rates also affect protein expression. However, pQTL studies reveal that protein-based mechanisms can buffer genetic alterations influencing mRNA expression, as many pQTLs are not associated with mRNA expression changes [17].

Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Regulation Studies

Table 6: Key Reagents for Gene Regulation Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 4-Thiouridine (4sU) | Metabolic RNA labeling for nascent transcript capture | 4sU-seq to measure transcription rates |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Grade Antibodies | Specific immunoprecipitation of chromatin-bound proteins or histone marks | ChIP-seq for TF binding (e.g., CTCF) or histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me3) |

| ATAC-seq Kits | Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin | Mapping open chromatin regions (caQTLs) |

| DNase I | Enzyme for digesting accessible chromatin | DNase-seq for mapping hypersensitive sites |

| Reverse Crosslinking Buffers | Release of protein-bound DNA complexes | ChIP-seq and CLIP-seq protocols |

Figure 3: A cascading model of how non-coding genetic variants influence molecular phenotypes across regulatory layers, ultimately contributing to complex traits and diseases.

For researchers and drug development professionals, establishing a direct causal relationship between genetic variation and phenotypic expression represents a fundamental challenge in modern genomics. While genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified thousands of correlations between genetic variants and traits, these statistical associations frequently fall short of demonstrating mechanistic causality [21]. The transition from correlation to causation requires rigorous functional validation protocols that can definitively link specific genetic alterations to their biochemical and physiological consequences.

The limitations of correlation-based approaches have become increasingly apparent. As noted in a recent analysis, "If such a once-in-a-lifetime genome test costs no more than a once-in-a-year routine physical exam, why aren't more people buying it and taking it seriously?" [21] This translation gap underscores the critical need for methods that can move beyond statistical association to establish true causal relationships. The following sections compare the leading experimental frameworks designed to address this challenge, providing researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for functional validation of genetic variants.

Established Correlation Methods: Foundations and Limitations

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Protocol Overview: GWAS methodology involves genotyping thousands of individuals across the genome using microarray technology, followed by statistical analysis comparing variant frequencies between case and control groups. The standard workflow includes quality control of genotyping data, imputation to increase variant coverage, population stratification correction, association testing, and multiple testing correction [22].

Key Performance Metrics:

- Typically requires sample sizes exceeding 10,000 individuals for common variants

- Genome-wide significance threshold: p < 5 × 10^-8

- Successful identification of >100,000 variant-trait associations to date

- Explanation of typically 5-20% of heritability for most complex traits

Technical Limitations: GWAS identifies statistical associations rather than causal variants. The interpretation is complicated by linkage disequilibrium, which makes it difficult to pinpoint the actual functional variant among correlated markers [22]. Additional challenges include inadequate representation of diverse populations, with over 80% of GWAS participants having European ancestry, limiting generalizability and equity of findings [21].

Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS)

Protocol Overview: PRS aggregate the effects of many genetic variants across the genome to estimate an individual's genetic predisposition for a particular trait or disease. The standard protocol involves using summary statistics from GWAS to weight individual risk alleles, which are then summed to create a composite risk score [21].

Performance Limitations: While PRS can achieve significant stratification for some conditions like coronary artery disease, their clinical utility remains limited. The March 2025 bankruptcy of 23andMe, once the flagship of direct-to-consumer genomics, serves as a stark reminder of the limited translational value of current PRS approaches [21].

Causal Validation Frameworks: Establishing Mechanism

Functional Genomics and Experimental Validation

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) established the PS3/BS3 criterion for "well-established" functional assays that can provide strong evidence for variant pathogenicity or benign impact [5]. However, implementation has been inconsistent, prompting the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group to develop a standardized four-step framework:

- Define the disease mechanism

- Evaluate the applicability of general classes of assays used in the field

- Evaluate the validity of specific instances of assays

- Apply evidence to individual variant interpretation [5]

This framework emphasizes that functional evidence from patient-derived material best reflects the organismal phenotype, though the level of evidence strength should be determined based on validation parameters including control variants and statistical rigor [5].

Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS)

Experimental Protocol: DMS uses massively parallel assays to comprehensively characterize variant effects by tracking genotype frequencies during selection experiments [23]. The technical workflow involves:

- Library Generation: Creating comprehensive variant libraries using oligonucleotide synthesis or error-prone PCR

- Selection System: Implementing a system that links genotype to phenotype (e.g., surface display, cellular fitness)

- Phenotypic Selection: Applying selective pressure (e.g., binding, enzymatic activity, cellular growth)

- Sequencing Quantification: Using high-throughput sequencing to quantify variant frequencies pre- and post-selection

Performance Advantages: DMS can simultaneously assay thousands to millions of variants in a single experiment, providing comprehensive functional maps. The original EMPIRIC experiment with yeast Hsp90 revealed a bimodal distribution of fitness effects, with "a fairly equal proportion of mutations being either strongly deleterious or nearly neutral" [23].

Figure 1: Deep Mutational Scanning Workflow for High-Throughput Functional Validation

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Table 1: Method Comparison for Establishing Genotype-Phenotype Links

| Method | Throughput | Functional Resolution | Causal Evidence | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | Very High (genome-wide) | Low (association only) | Correlation only | Initial variant discovery, risk locus identification |

| Family Studies | Low (pedigree-based) | Moderate (segregation) | Suggestive | Mendelian disorders, de novo mutations |

| Functional Genomics (targeted) | Medium (gene-focused) | High (molecular mechanism) | Strong | Variant pathogenicity, clinical interpretation |

| Deep Mutational Scanning | High (comprehensive variant sets) | High (quantitative effects) | Strong to definitive | Functional maps, variant effect prediction |

| Clinical-Genetic Correlation | Medium (patient cohorts) | Moderate (clinical severity) | Moderate | Genotype-phenotype correlations, prognostic prediction |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Genotype-Phenotype Methods

| Method | Typical Timeline | Cost Range | Variant Capacity | Evidence Level (ACMG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | 6-18 months | $100K-$1M+ | 1M-10M variants | Supporting (PP1) |

| Targeted Functional Assays | 3-12 months | $50K-$200K | 1-100 variants | Strong (PS3/BS3) |

| DMS | 2-6 months | $100K-$300K | 1K-1M variants | Strong to Very Strong |

| Clinical Correlation Studies | 12-24 months | $200K-$500K | 10-1000 patients | Moderate (PP4) |

Case Studies in Causal Validation

Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Genotype Determines Phenotypic Severity

A 2023 study of 3,494 children with familial hypercholesterolemia demonstrated a clear genotype-phenotype relationship, showing that "receptor negative variants are associated with significant higher LDL-C levels in HeFH patients than receptor defective variants (6.0 versus 4.9 mmol/L; p < 0.001)" [24]. This large-scale analysis established that specific mutation types directly influence disease severity, with significant implications for treatment selection. The study further found that "significantly more premature CVD is present in close relatives of children with HeFH with negative variants compared to close relatives of HeFH children with defective variants (75% vs 59%; p < 0.001)" [24], providing compelling evidence for the clinical impact of specific genetic variants.

Phenylketonuria: Genotype-Based Phenotype Prediction

A comprehensive study of 1,079 Chinese patients with phenylketonuria established definitive genotype-phenotype correlations, identifying specific PAH gene mutations associated with disease severity [25]. The research demonstrated that "null + null genotypes, including four homoallelic and eleven heteroallelic genotypes, were clearly associated with classic PKU" [25], while other specific genotypes correlated with mild PKU or mild hyperphenylalaninaemia. This systematic correlation provides a framework for predicting disease severity from genetic information alone, enabling personalized treatment approaches.

Figure 2: Established Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Phenylketonuria

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Validation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms | Variant detection and quantification | High-throughput, multiplexing capability | Illumina NextSeq 550, PacBio Sequel |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing | Gene knockout, knock-in, base editing | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, Cas12a |

| Viral Delivery Vectors | Gene transfer | High transduction efficiency | Lentivirus, AAV, Adenovirus |

| Surface Display Systems | Protein variant screening | Genotype-phenotype linkage | Phage display, yeast display |

| Variant Annotation Tools | Functional prediction | HGVS nomenclature standardization | Alamut Batch, VEP, ANNOVAR |

| Cell Model Systems | Functional characterization | Physiological relevance | iPSCs, organoids, primary cells |

Methodological Considerations and Best Practices

Assay Validation and Controls

The ClinGen SVI Working Group recommends that functional assays include a minimum of 11 total pathogenic and benign variant controls to reach moderate-level evidence in the absence of rigorous statistical analysis [5]. Proper validation should demonstrate:

- Concordance with known pathogenic and benign controls

- Reproducibility across experimental replicates

- Appropriate dynamic range to detect relevant effects

- Technical robustness with minimal variability

Addressing Variants of Uncertain Significance

The interpretation of rare genetic variants of unknown clinical significance represents one of the main challenges in human molecular genetics [26]. A conclusive diagnosis is critical for patients to obtain certainty about disease cause, for clinicians to provide optimal care, and for genetic counselors to advise family members. Functional studies provide key evidence to change a possible diagnosis into a certain diagnosis [26].

Future Directions and Translational Applications

Artificial Intelligence and Predictive Modeling

The transformative rise of artificial intelligence exemplifies unprecedented power in predicting protein structures and variant effects [21]. AlphaFold and similar approaches promise to enhance our ability to predict variant impact from sequence alone, potentially reducing the need for laborious experimental validation for some applications.

Diverse Population Representation

Current GWAS face significant limitations due to inadequate samples for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) [21]. Over 80% of GWAS participants have European ancestry, creating major limitations for generalizability and equity. Future research must prioritize inclusion of diverse ancestral backgrounds to ensure genetic discoveries benefit all populations.

Establishing a direct link between genotype and phenotype requires integration of multiple evidence types, from statistical association in human populations to functional validation in experimental systems. While GWAS provides initial correlation data, conclusive evidence of causation demands functional studies that demonstrate the mechanistic impact of genetic variants on molecular, cellular, and physiological processes. The frameworks and methodologies compared in this analysis provide researchers with a roadmap for transitioning from correlation to causation, ultimately enabling more precise genetic medicine and targeted therapeutic development.

As the field advances, cooperation between computational and biological scientists will be essential for aligning computational predictions with experimental validation, leading to improved estimations of variant impact and a better understanding of the fundamental genotype-phenotype relationship [27]. This collaborative approach promises to accelerate our ability to translate genetic discoveries into clinical applications that improve human health.

A Toolkit for Researchers: From Classic Assays to High-Throughput Functional Genomics

Saturation Genome Editing (SGE) is a CRISPR-Cas9-based methodology that enables the functional characterization of thousands of genetic variants by introducing exhaustive nucleotide modifications into their native genomic context [28] [29]. This approach represents a significant shift from traditional methods, which often analyzed variants in isolation or outside of their native chromosomal environment, potentially missing critical contextual influences from regulatory elements, epigenetic marks, and endogenous expression patterns [29]. By preserving this native context, SGE provides a more physiologically relevant assessment of variant impact, making it particularly valuable for resolving Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in clinical genomics and for basic research into gene function [30] [31].

The foundational principle of SGE leverages programmable nucleases to create DNA double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci, which are then repaired via homology-directed repair (HDR) using synthesized donor libraries containing saturating mutations [29]. When applied to genes essential for cell survival, functional deficiencies caused by introduced variants result in depletion of those variant-containing cells from the population over time, enabling quantitative assessment of variant effect through deep sequencing [28] [30]. This methodology has now been systematically applied to key disease genes including BRCA1, BRCA2, and BAP1, generating comprehensive functional atlases that correlate variant effects with clinical phenotypes [32] [31] [33].

Comparative Analysis of SGE Methodologies

Platform Specifications and Performance Metrics

SGE implementations vary in their technical specifications, experimental designs, and analytical approaches. The table below compares key methodological features across major SGE studies and platforms.

Table 1: Comparative Specifications of SGE Experimental Platforms

| Parameter | Foundational SGE (2014) | BRCA1 SGE (2018) | BRCA2 SGE (2025) | HAP1-A5 Platform (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Regions | BRCA1 exon 18 (78 bp), DBR1 (75 bp) [29] | RING & BRCT domains (13 exons) [30] | DNA-binding domain (exons 15-26) [31] | Flexible target regions ≤245 bp [28] |

| Cell Line | HEK293T, HAP1 [29] | HAP1 [30] | HAP1 [31] | HAP1-A5 (LIG4 KO, Cas9+) [28] |

| Variant Types | SNVs, hexamers, indels [29] | 3,893 SNVs [30] | 6,959 SNVs [31] | SNVs, indels, codon scans [28] |

| Editing Efficiency | 1.02-3.33% [29] | Not specified | Not specified | High (LIG4 KO enhances HDR) [28] [33] |

| Selection Readout | Transcript abundance (BRCA1), cell growth (DBR1) [29] | Cell fitness (essential gene) [30] | Cell viability (essential gene) [31] | Cell fitness over time (14-21 days) [28] |

| Functional Classification | Enrichment scores [29] | Functional (72.5%), Intermediate (6.4%), LOF (21.1%) [30] | Bayesian pathogenicity probabilities (7 categories) [31] | Functional scores for all SNVs [28] |

Quantitative Outcomes Across Gene Targets

The functional impact of variants measured by SGE shows consistent patterns across genes, with clear separation between synonymous, missense, and nonsense variants. The following table summarizes quantitative outcomes from major SGE studies.

Table 2: Comparative Functional Outcomes Across SGE Studies

| Study | Gene | Synonymous Variants (Median Score) | Missense Variants (Median Score) | Nonsense Variants (Median Score) | Classification System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 (2018) [30] | BRCA1 | 0 (log2 scaled reference) | Variable distribution | -2.12 (log2 scaled) | 3-class: FUNC/INT/LOF |

| DBR1 (2014) [29] | DBR1 | Near wild-type (1.006-fold) | 73-fold depletion | 207-fold depletion | Enrichment scores |

| BRCA2 (2025) [31] | BRCA2 | 98.8% benign categories | 13.3% pathogenic, 84.6% benign | 100% pathogenic categories | 7-category Bayesian |

| Clinical Correlation [32] | BRCA1 | Not associated with cancer | Variable by functional class | Strong cancer association | Clinical diagnosis correlation |

Advantages Over Alternative Functional Assays

SGE occupies a distinctive position in the landscape of functional genomics technologies. The table below compares its key attributes against alternative approaches for variant functional assessment.

Table 3: SGE in Context of Alternative Functional Assessment Methods

| Method | Native Context | Throughput | Quantitative Resolution | Clinical Concordance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturation Genome Editing | Yes (endogenous locus) [29] | High (thousands of variants) [28] | Continuous functional scores [30] | 93-99% with clinical data [32] [31] | Variant classification, functional atlas generation |

| Homology-Directed Repair Assay | No (reporter systems) [31] | Low-medium (single variants) [31] | Binary or semi-quantitative [31] | 93-95% with SGE [31] | Specific functional pathways |

| Minigene Splicing Assays | No (artificial constructs) [29] | Medium (dozens of variants) | Categorical (splicing impact) | Variable | Splice variant assessment |

| Deep Mutational Scanning | No (cDNA overexpression) [33] | High (thousands of variants) [33] | Continuous scores | Limited validation | Protein function mapping |

| Model Organisms | No (cross-species) | Low-medium | Organism-level phenotypes | Species-dependent | Biological pathway analysis |

Detailed SGE Experimental Protocol

Core Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The SGE methodology follows a systematic workflow from library design to functional scoring. The diagram below illustrates the core experimental process.

Step-by-Step Protocol Implementation

Library Design and sgRNA Selection (Timing: 1-2 weeks)

SGE begins with computational design of variant libraries and corresponding sgRNAs. The VaLiAnT software is typically used to design SGE variant oligonucleotide libraries [28]. Target regions generally include coding exons with adjacent intronic or untranslated regions (UTRs), with a maximum variant-containing region of ~245 bp within a total target region of ~300 bp to accommodate high-quality oligonucleotide synthesis [28]. Libraries can include single nucleotide variants (SNVs), in-frame codon deletions, alanine and stop-codon scans, all possible missense changes, 1 bp deletions, and tandem deletions for splice-site scanning [28]. Custom variants from databases like ClinVar and gnomAD can also be incorporated via Variant Call Format (VCF) files [28].

For each SGE HDR template library, a corresponding sgRNA is selected to target the specific genomic region for editing [28]. The sgRNA design incorporates synonymous PAM/protospacer protection edits (PPEs) within the SGE HDR template library target region to prevent re-cleavage of already-edited loci [28]. These fixed changes ensure that successfully edited genomic regions are no longer recognized by the Cas9-sgRNA complex, thereby minimizing repeated cutting and enhancing editing efficiency.

Cell Line Preparation and Validation (Timing: 1-2 weeks)

The HAP1-A5 cell line (HZGHC-LIG4-Cas9) serves as the primary cellular platform for SGE experiments [28]. This adherent, near-haploid cell line derived from the KBM-7 chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line offers several advantages: (1) a DNA Ligase 4 (LIG4) gene knockout (10 bp deletion) that biases DNA repair toward HDR rather than non-homologous end joining (NHEJ); (2) stable genomic Cas9 integration ensuring high Cas9 activity; and (3) maintained haploidy that allows recessive phenotypes to manifest with single-allele editing [28] [33].

Before initiating SGE screens, researchers must validate gene essentiality in HAP1-A5 cells through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout followed by cell counting, colony assays, or flow cytometry with annexin-V/DAPI staining [28]. Additionally, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis is critical to confirm haploidy of cell stocks, as HAP1 cells can increase in ploidy with prolonged culture [28]. HAP1-A5 cells sorted for high haploidy exhibit minimal haploidy loss (<3% between thawing and editing, <5% between editing and final passage in a three-week SGE screen) [28].

Nucleofection and Selection (Timing: 2-3 days)

HAP1-A5 cells are nucleofected with both the SGE HDR template library and the corresponding sgRNA vector [28]. For genes essential in HAP1-A5 cells, variants that compromise gene function become depleted from the edited cell population over time due to impaired cell fitness [28] [30]. Following nucleofection, cells undergo puromycin selection to generate a population where each cell contains a single variant, typically achieving HDR efficiencies of 1-3% [28] [29].

To maintain good representation of SGE variant installation complexity, 5-6 million cells are collected for each replicate time point [28]. The editing efficiency can be enhanced by using HAP1 LIG4 KO cells, which have higher rates of HDR due to the biased repair pathway [33]. The haploid nature of these cells allows variant effects to be measured without interference from wild-type alleles, which is particularly important for variants with loss-of-function mechanisms [28].

Time-Course Sampling and Sequencing (Timing: 14-21 days culture + 1 week processing)

Edited cells are cultured for 14 or 21 days total, with Day 4 serving as the baseline time point and additional time points collected between baseline and terminal samples to enable variant kinetics calculation [28]. Genomic DNA is extracted from time point replicates, and SGE-edited gDNA is converted to NGS libraries using target-specific primer sets [28]. These libraries undergo deep amplicon sequencing to quantify relative variant abundances across time points [28].

The sequencing depth must be sufficient to detect even low-frequency variants, with typical studies achieving 3,500-4,000 reads per variant per time point [31]. The resulting count data enables calculation of enrichment scores (later time point counts divided by baseline counts) or log2-transformed fold changes, which serve as raw functional scores for each variant [29] [31].

Data Analysis and Functional Classification (Timing: 1-2 weeks)

Variant frequencies at each time point are calculated as the ratio of variant read counts to total reads [31]. Position-dependent effects are adjusted using replicate-level generalized additive models with target-region-specific adaptive splines [31]. For essential genes, nonsense variants typically serve as pathogenic controls, while synonymous variants serve as benign controls [31].

Statistical frameworks like the VarCall Bayesian model assign posterior probabilities of pathogenicity based on functional scores [31]. This model embeds a Gaussian two-component mixture model, with nonsense variants assumed pathogenic and silent variants (lacking splice effects) assumed benign [31]. The method adjusts for batch effects using replicate data with targeted region location and scale random effects, employing Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms to obtain adjusted mean functional scores [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents required for implementing SGE protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Saturation Genome Editing

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Function in Protocol | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line | HAP1-A5 (HZGHC-LIG4-Cas9) LIG4 KO, Cas9+ | Provides optimized cellular platform with enhanced HDR efficiency | Horizon Discovery/Revvity [28] [33] |

| Oligo Library | Array-synthesized pool, ≤245 bp variant region | Serves as HDR template introducing saturating mutations | Twist Bioscience [28] |

| sgRNA Vector | AmpR/PuroR resistance cassettes | Enables selection in E. coli and human cells; guides Cas9 to target | Custom cloning [28] |

| Nucleofection System | High-efficiency transfection | Delivers sgRNA and HDR template libraries to cells | Various commercial systems |

| Selection Antibiotics | Puromycin | Selects for successfully transfected cells | Various suppliers |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Amplicon-based sequencing | Prepares sequencing libraries from gDNA | Illumina-compatible kits |

| Analysis Software | VaLiAnT, VarCall model | Designs libraries and analyzes functional scores | Publicly available [28] [31] |

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Critical Protocol Parameters

Successful SGE implementation requires careful optimization of several parameters. Editing efficiency depends strongly on sgRNA efficacy and the cellular repair environment, with LIG4 knockout cells typically achieving 1.14-3.33% HDR efficiency [29] [33]. The haploid nature of HAP1 cells must be regularly monitored via FACS, as ploidy increases during prolonged culture can introduce noise [28]. Library complexity maintenance requires large cell numbers (5-6 million per time point) and adequate sequencing depth (>3,500 reads per variant) to ensure reliable detection of even depleted variants [28] [31].

Temporal sampling design significantly impacts result quality. While early time points (day 4-5) establish baseline variant representation, later time points (day 14-21) reveal fitness effects through differential depletion [28] [31]. The optimal culture duration depends on the strength of selection, which varies by gene essentiality. Triplicate biological replicates are essential for statistical robustness, with correlation between replicates (R > 0.65) indicating good experimental quality [29].

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

Common SGE challenges include low HDR efficiency, which can be addressed by optimizing sgRNA design, using early-passage cells, and implementing HDR-enhancing modifications like LIG4 knockout [28] [33]. Bottlenecking during transfection—where limited numbers of cells receive the variant library—can reduce variant representation; this is minimized by scaling transfection to sufficient cell numbers (e.g., 5 million cells for HAP1 transfections) [29] [31].

Position effects within target regions may confound functional scores, necessitating computational correction using methods like generalized additive models with region-specific splines [31]. Inadequate sequencing depth for low-abundance variants can be addressed by increasing read depth or implementing unique molecular identifiers to reduce amplification bias.

Validation and Clinical Translation

Correlation with Clinical Phenotypes

SGE functional classifications demonstrate strong concordance with clinical observations. In a landmark validation study, BRCA1 variants classified as functionally abnormal by SGE showed significant association with BRCA1-related cancer diagnoses in the DiscovEHR cohort, which linked exome sequencing data with electronic health records from 92,453 participants [32]. This clinical correlation validates SGE's predictive value for variant pathogenicity in real-world populations.

For BRCA2, SGE functional assessments of 6,959 variants achieved >99% sensitivity and specificity when validated against known pathogenic and benign variants from ClinVar [31]. Similarly, comparison with an established homology-directed repair functional assay demonstrated 93% sensitivity and 95% specificity [31]. These high validation metrics support the use of SGE data as evidence for variant classification in clinical guidelines.

Integration with Variant Interpretation Guidelines

SGE results can be integrated into existing variant interpretation frameworks, including the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines [31]. The functional data provides PS3/BS3 evidence (functional data supporting pathogenicity/benignity), with strength determined by posterior probabilities from Bayesian models [31]. For BRCA2, this integration enabled classification of 91% of variants as either pathogenic/likely pathogenic or benign/likely benign, substantially reducing variants of uncertain significance [31].

The creation of public databases housing SGE results, such as the Atlas of Variant Effects Alliance, promotes data sharing and clinical utilization [33]. These resources aim to preemptively characterize variants before they are encountered in clinical settings, potentially accelerating diagnosis and appropriate patient management.

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized functional genomics, enabling researchers to systematically interrogate gene function from individual variants to genome-wide scales. As the technology matures, optimizing workflow efficiency and reliability has become paramount for both basic research and therapeutic development. This guide objectively compares the performance of different CRISPR-Cas9 approaches and reagents, providing experimental data to inform selection for specific applications within genetic variant functional validation protocols. We examine key methodological considerations including guide RNA design, delivery systems, and analytical frameworks that impact experimental outcomes across varying scales.

Table of Contents

- Comparison of CRISPR Workflow Scales

- Performance Benchmarking of CRISPR Tools

- Single-Variant Editing Protocols

- Genome-Wide Screening Approaches

- Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

- Visualized Experimental Workflows

Comparison of CRISPR Workflow Scales

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology spans distinct workflow categories, each with unique experimental requirements and performance considerations.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow Scales

| Workflow Scale | Primary Applications | Key Technical Considerations | Typical Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Variant Editing | Functional characterization of specific genetic variants; therapeutic development | Editing precision; off-target effects; delivery efficiency | Individual to dozens of targets |

| Focused Library Screening | Pathway analysis; drug target validation; non-coding element characterization | Library size optimization; multiplexed delivery; phenotypic readouts | Hundreds to thousands of targets |

| Genome-Wide Screening | Gene essentiality mapping; functional genomics; drug resistance mechanisms | Library comprehensiveness; screening cost; data analysis complexity | Whole genome coverage (20,000+ genes) |

Performance Benchmarking of CRISPR Tools

Guide RNA Library Performance

Recent systematic benchmarking provides critical insights into guide RNA (gRNA) library performance. One comprehensive study compared six established genome-wide libraries (Brunello, Croatan, Gattinara, Gecko V2, Toronto v3, and Yusa v3) using a unified essentiality screening framework in multiple colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT116, HT-29, RKO, and SW480) [34].

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of CRISPR gRNA Libraries in Essentiality Screens

| Library Name | Guides Per Gene | Relative Depletion Efficiency* | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top3-VBC | 3 | Highest | Guides selected by Vienna Bioactivity score |

| Yusa v3 | ~6 | High | Balanced performance across cell types |

| Croatan | ~10 | High | Dual-targeting approach |

| Toronto v3 | ~4 | Moderate | Widely adopted standard |

| Brunello | ~4 | Moderate | Improved on-target efficiency |

| Bottom3-VBC | 3 | Lowest | Demonstrates importance of guide selection |

*Relative depletion efficiency of essential genes based on Chronos gene fitness estimates [34].

The Vienna library (utilizing top VBC-scored guides) demonstrated particularly strong performance, with the top 3 VBC-guided sequences per gene showing equal or better essential gene depletion compared to libraries with more guides per gene [34]. This finding has significant implications for library design, suggesting that smaller, more precisely selected libraries can reduce costs and increase feasibility without sacrificing performance.

Single vs. Dual-Targeting Approaches

Dual-CRISPR systems, which employ two gRNAs to delete genomic regions, offer distinct advantages for certain applications:

- Enhanced Knockout Efficiency: Dual-guide approaches create defined deletions between target sites, potentially generating more complete knockouts than single guides relying on error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [34].

- Non-Coding Element Characterization: Paired gRNAs enable systematic deletion of non-coding regulatory elements (NCREs), facilitating functional studies of enhancers, silencers, and other regulatory regions [35].

- Potential Drawbacks: Dual-targeting may trigger heightened DNA damage response compared to single guides, as evidenced by a log₂-fold change delta of -0.9 (dual minus single) in non-essential genes, possibly reflecting fitness costs from creating twice the number of double-strand breaks [34].

Single-Variant Editing Protocols

Saturation Genome Editing for Functional Validation

Saturation genome editing (SGE) represents a powerful approach for functional characterization of genetic variants. This method combines CRISPR-Cas9 with homology-directed repair (HDR) to exhaustively introduce nucleotide modifications at specific genomic sites in multiplex, enabling functional analysis while preserving native genomic context [8].

Key Protocol Steps [8]:

- Variant Library Design: Comprehensive coverage of all possible nucleotide substitutions at target genomic regions

- sgRNA and Donor Template Design: Selection of high-efficiency guides with minimal off-target potential and synthesis of HDR donor templates

- Cell Line Selection: Utilization of appropriate cellular models (e.g., HAP1-A5 cells) that support efficient HDR

- Library Delivery and Screening: Introduction of variant libraries via lentiviral delivery followed by phenotypic selection

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Library Preparation: Barcoded amplification and sequencing of enriched/depleted variants

- Functional Scoring: Quantitative assessment of variant effects based on enrichment patterns

This approach has been successfully applied to classify pathogenicity of germline and somatic variation in genes such as DDX3X, BAP1, and RAD51C, providing functional evidence for variant interpretation [8].

Enhancing Editing Efficiency Through Nuclear Localization

Efficient nuclear entry of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes remains a critical bottleneck in editing efficiency. Recent innovations address this challenge through engineered nuclear localization signal (NLS) configurations:

- Hairpin Internal NLS (hiNLS): Insertion of tandem NLS motifs into surface-exposed loops of Cas9, creating a more even distribution across the protein structure compared to traditional terminal NLS tags [36].

- Improved Editing Rates: hiNLS-Cas9 variants demonstrated enhanced performance in primary human T cells, with one variant (s-M1M4) achieving B2M knockout in over 80% of cells compared to approximately 66% with traditional Cas9 when delivered via electroporation [36].

- Therapeutic Relevance: This approach is particularly valuable for clinical applications where transient RNP delivery is preferred, as it maximizes editing within the brief therapeutic window [36].

Genome-Wide Screening Approaches

Dual-CRISPR Systems for Non-Coding Element Characterization

Genome-wide screening of non-coding regulatory elements (NCREs) presents unique challenges, as these regions often span 50-200 bp with multiple transcription factor binding sites. A recently developed dual-CRISPR screening system enables systematic deletion of thousands of NCREs to study their functions in distinct biological contexts [35].

Key Methodological Innovations [35]:

- Convergent Promoter Design: Arrangement of U6 and H1 promoters in convergent orientation to drive expression of two guide RNAs from a single vector

- Paired gRNA Library Design: Comprehensive targeting of both ends of NCREs, including 4,047 ultra-conserved elements (UCEs) and 1,527 validated enhancers

- Streamlined Cloning Strategy: Two-step assembly process first incorporating paired crRNA sequences followed by tracrRNA scaffold insertion

- Direct Amplification Compatibility: Library design enabling PCR amplification of paired guide sequences for high-throughput sequencing

This system identified essential regulatory elements, including the discovery that many ultra-conserved elements possess silencer activity and play critical roles in cell growth and drug response [35]. For example, deletion of the ultra-conserved element PAX6_Tarzan from human embryonic stem cells led to defects in cardiomyocyte differentiation, highlighting the utility of this approach for uncovering novel developmental regulators [35].

Library Size Optimization and Performance

The development of minimal genome-wide CRISPR libraries addresses practical constraints while maintaining screening performance:

- Size Reduction: New library designs achieve 50% reduction in size compared to conventional libraries while preserving sensitivity and specificity [34].

- Improved Cost-Effectiveness: Smaller libraries reduce reagent and sequencing costs, enabling broader deployment in resource-limited settings or complex models like organoids and in vivo systems [34].

- Performance Validation: In osimertinib resistance screens using HCC827 and PC9 lung adenocarcinoma cells, the minimal Vienna-single (3 guides/gene) and Vienna-dual libraries consistently showed stronger resistance log fold changes for validated resistance genes compared to the larger Yusa v3 library [34].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Variants | SpCas9, NmeCas9, GeoCas9 | DNA cleavage; targeting flexibility | NmeCas9 offers higher specificity; GeoCas9 functions at higher temperatures [37] |

| Guide RNA Libraries | Vienna-single, Yusa v3, Brunello | Gene targeting; screening comprehensiveness | Vienna library demonstrates superior performance with fewer guides [34] |

| Delivery Systems | Electroporation, PERC, Lentivirus | Cellular introduction of editing components | PERC is gentler than electroporation with less impact on viability [36] |

| Design Algorithms | VBC scores, Rule Set 3 | gRNA efficiency prediction | VBC scores negatively correlate with log-fold changes of essential gene targeting guides [34] |

| Analysis Tools | MAGeCK, Chronos | Screen data analysis; hit identification | Chronos models time-series data for improved fitness estimates [34] |

Visualized Experimental Workflows

Single-Variant Editing Workflow

Dual-CRISPR Screening Workflow

Advanced Nuclear Localization Strategy

The evolving CRISPR-Cas9 workflow landscape offers researchers multiple paths for functional validation of genetic variants, each with distinct performance characteristics. Single-variant editing approaches like saturation genome editing provide high-resolution functional data for precise variant interpretation, while optimized genome-wide screening platforms enable systematic discovery of gene function and regulatory elements. Critical to success is the selection of appropriately designed gRNA libraries, with emerging evidence supporting the efficacy of smaller, more strategically designed libraries over larger conventional collections. Dual-guide systems expand capabilities for studying non-coding regions but require consideration of potential DNA damage response activation. As the field advances, integration of improved nuclear delivery strategies and continued refinement of bioinformatic tools will further enhance the precision and efficiency of CRISPR-based functional genomics across all workflow scales.

Functional assays are indispensable tools in genetic research and drug development, providing critical evidence for validating the impact of genetic variants. While genomic sequencing can identify sequence alterations, functional assays are required to confirm the mechanistic consequences on biological processes such as pre-mRNA splicing, enzymatic function, and protein folding stability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three fundamental assay categories—splicing (minigene), enzymatic activity, and protein stability—framed within the context of functional validation for genetic variants. We present objective performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions to inform researchers' experimental design decisions.

Splicing Assays: Minigene Approach