Functional Validation of Genetic Variants: From VUS to Pathogenicity in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the functional validation of genetic variants for researchers and drug development professionals.

Functional Validation of Genetic Variants: From VUS to Pathogenicity in Biomedical Research

Abstract

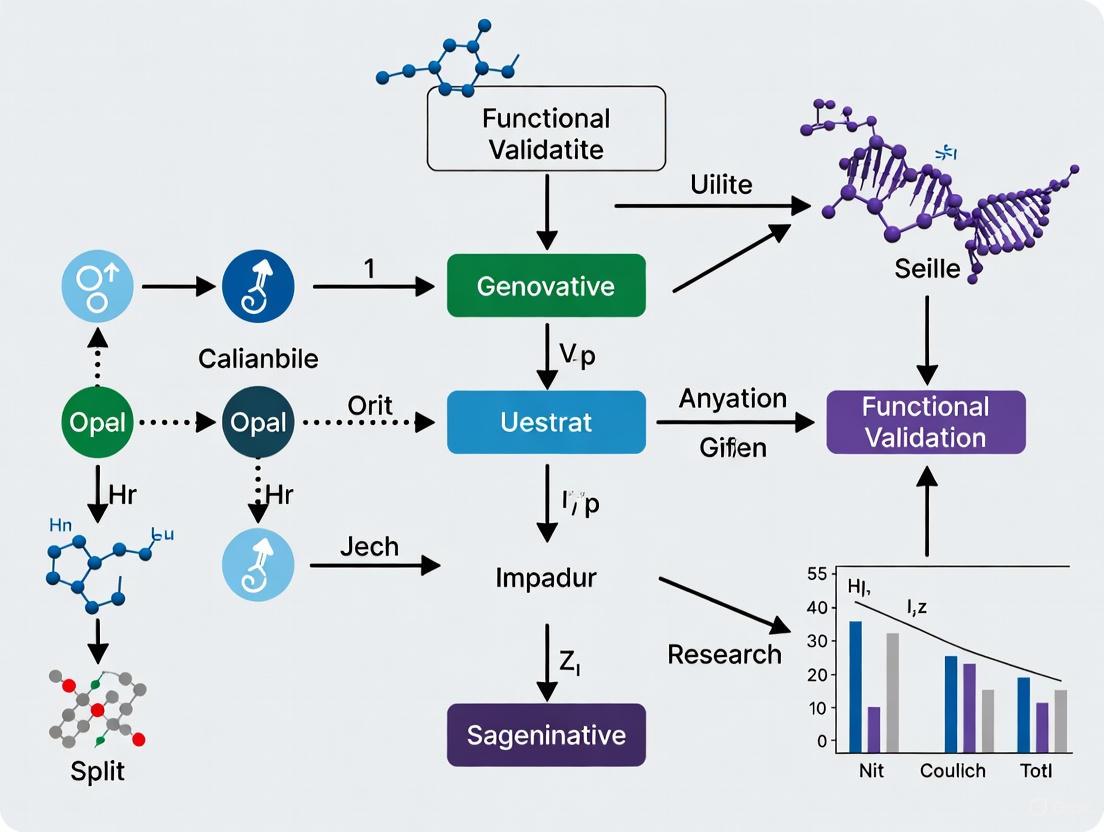

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the functional validation of genetic variants for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the critical challenge of interpreting Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) discovered via next-generation sequencing and outlines a complete workflow from foundational concepts to advanced applications. The content explores established and emerging methodological approaches, including specific biochemical, cellular, and computational assays. It also addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for validation pipelines and concludes with frameworks for rigorous validation and comparative analysis to ensure results are clinically actionable and reproducible.

The VUS Challenge: Establishing the Need for Functional Validation

Defining Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) and Their Clinical Impact

A Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) is a genetic alteration for which the impact on health and disease risk is currently unknown [1]. These variants represent a significant bottleneck in clinical genetics, as they cannot be definitively classified as either pathogenic or benign based on existing evidence. The high likelihood that a newly observed variant will be a VUS has made interpretation of genetic variants a substantial challenge in clinical practice [2]. Furthermore, variants identified in individuals of non-European ancestries are often confounded by the limited diversity of population databases, causing substantial inequity in diagnosis and treatment [3] [2].

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), and the Association for Clinical Science (ACGS) have established standard guidelines for interpreting variants, introducing clear categories: benign, likely benign, pathogenic, likely pathogenic, and VUS [1]. These classifications are based on multiple factors including population data, computational predictions, functional evidence, and segregation data. As of October 2024, the majority of variants associated with rare diseases in the ClinVar database were categorized as VUS, highlighting the critical need for improved classification strategies [1].

Clinical Challenges and Impact of VUS

Prevalence and Reclassification Rates

VUS prevalence varies significantly across populations, with underrepresented groups often experiencing higher rates due to limited representation in genomic databases [3]. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies on VUS prevalence and reclassification:

Table 1: VUS Prevalence and Reclassification Data from Recent Studies

| Study Population | VUS Prevalence | Reclassification Rate | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levantine HBOC patients | 40% of participants had non-informative results (VUS) | 32.5% of VUS reclassified | 4 VUS upgraded to Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic; median of 4 total VUS per patient | [3] |

| Seven tumor suppressor genes (NF1, TSC1, etc.) | 128 unique VUS from 145 carriers | 31.4% reclassified as Likely Pathogenic using new criteria | STK11 showed highest reclassification rate (88.9%) | [4] |

| TP53 germline variants (Li-Fraumeni syndrome) | Specific rate not provided | Updated specifications led to clinically meaningful classifications for 93% of pilot variants | New Bayesian-informed approach reduced VUS rates and increased certainty | [5] |

Psychological and Clinical Management Challenges

The disclosure of uncertain genetic results exacerbates the psychological burden associated with genetic testing. Ambiguous testing results are associated with negative patient reactions including:

- Over-interpretation and anxiety about disease risk

- Frustration and hopelessness regarding preventive measures

- Decisional regret about treatment choices [3]

Studies show that participants with uncertain results have higher difficulty understanding and recalling the outcome of their genetic tests [3]. Negative reactions are particularly prevalent in cancer patients, possibly due to heightened anxiety about the disease, uncertainty in decision-making regarding treatment or prophylactic surgery, and the emotional burden of hereditary risks [3].

From a clinical management perspective, VUS create significant challenges for:

- Treatment decisions: Physicians are often hesitant to implement aggressive preventive measures based on VUS results

- Family screening: Relatives cannot be effectively tested for a VUS with unclear significance

- Resource utilization: VUS require ongoing reinterpretation and tracking, consuming substantial healthcare resources

Misinterpretation of VUS as pathogenic or benign variants is common, resulting in erroneous expectations of their clinical impact [3]. This highlights the critical need for improved functional validation strategies to resolve VUS classifications.

Experimental Approaches for VUS Resolution

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Technologies

Single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) is a recently developed technology that enables simultaneous profiling of up to 480 genomic DNA loci and genes in thousands of single cells [6]. This method allows accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated gene expression changes, providing a powerful platform to dissect regulatory mechanisms encoded by genetic variants.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Utility in VUS Resolution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tapestri Technology (Mission Bio) | Microfluidic platform for single-cell multi-omics | Enables high-throughput targeted DNA and RNA sequencing at single-cell resolution | [6] |

| Prime Editing Systems | Precise genome editing without double-strand breaks | Scalable introduction of variants in endogenous genomic context for functional assessment | [7] |

| gnomAD Database | Population frequency data for genetic variants | Provides essential allele frequency data for PM2/BS1 ACMG criteria application | [3] [5] |

| REVEL & SpliceAI | In silico prediction algorithms | Computational prediction of variant deleteriousness and splice effects | [4] |

| ClinGen ER (Evidence Repository) | Centralized database for variant evidence | Enables collaborative curation and evidence sharing across institutions | [5] |

SDR-seq Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Cells are dissociated into a single-cell suspension, fixed with paraformaldehyde or glyoxal, and permeabilized

- In Situ Reverse Transcription: Custom poly(dT) primers add unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), sample barcodes, and capture sequences to cDNA molecules

- Droplet Generation: Cells containing cDNA and gDNA are loaded onto the Tapestri platform for first droplet generation

- Cell Lysis: Cells are lysed and treated with proteinase K, then mixed with reverse primers for each intended gDNA or RNA target

- Second Droplet Generation: Forward primers with capture sequence overhangs, PCR reagents, and barcoding beads are introduced

- Multiplexed PCR: Amplification of both gDNA and RNA targets within each droplet enables cell barcoding

- Library Preparation: Sequencing-ready libraries are generated with distinct overhangs for gDNA and RNA targets to optimize sequencing [6]

This methodology enables highly sensitive detection of DNA and RNA targets across thousands of single cells in a single experiment, with minimal cross-contamination between cells (<0.16% for gDNA, 0.8-1.6% for RNA) [6].

Multiplexed Assays of Variant Effect (MAVEs)

Multiplexed Assays of Variant Effect (MAVEs) enable scalable functional assessment of nearly all possible coding variants in a target sequence, offering a proactive approach to resolving VUS [8]. These high-throughput methods systematically measure the functional impact of thousands of variants in parallel, creating comprehensive maps of variant effects.

Prime Editing MAVE Protocol:

- Platform Development: Establish a pooled prime editing platform in HAP1 cells to assay variants in their endogenous genomic context

- pegRNA Optimization: Design and test prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) configurations for efficient variant installation

- Cell Enrichment: Implement co-selection strategies for edited cells and include surrogate targets to enhance data quality

- Selection Screening:

- Negative Selection: Screen for loss-of-function variants by measuring depletion of efficiently installed variants (e.g., >7,500 pegRNAs targeting SMARCB1)

- Positive Selection: Identify functional variants under selective pressure (e.g., 6-thioguanine selection for MLH1 LoF variants)

- Variant Assessment: Test both coding and non-coding variants, including a high proportion of all possible single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in target regions [7]

This platform has demonstrated high accuracy for discriminating pathogenic variants, making it valuable for identifying new disease-associated variants across large genomic regions [7].

Updated Variant Classification Frameworks

Recent advances in variant classification include updated, quantitative frameworks that incorporate Bayesian approaches and gene-specific specifications:

ClinGen TP53 VCEP v2 Specifications:

- Population Data (PM2): Updated thresholds for variant rarity (PM2 allele frequency < 0.00003) with adjustments for clonal hematopoiesis by examining variant allele fraction (VAF > 0.35)

- Functional Data (PS3/BS3): Incorporation of quantitative likelihood ratios from multiplexed functional assays

- Phenotype Evidence (PP4): Reintroduction of phenotype specificity criteria with modified scoring based on disease-specific diagnostic yields

- Computational Evidence (PP3/BP4): Updated thresholds for REVEL (≥0.7 for PP3, <0.2 for BP4) and SpliceAI (≥0.2 for PP3, <0.1 for BP4) predictions [4] [5]

New ClinGen PP1/PP4 Criteria: The updated PP1/PP4 criteria incorporate a point-based system that assigns higher scores based on phenotype specificity when phenotypes are highly specific to the gene of interest [4]. This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in VUS reclassification rates, particularly for tumor suppressor genes with characteristic phenotypes such as NF1, TSC1/TSC2, and STK11 [4].

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

International Standards and Data Sharing

The ClinGen/AVE Functional Data Working Group, comprising over 25 international members from academia, government, and industry, is developing more definitive guidelines for genetic variant classification [2]. Key objectives include:

- Developing clear, robust guidelines acceptable to clinical diagnostic scientists and clinicians

- Fostering partnerships with Variant Curation Expert Panels (VCEPs) to enable utilization of multiplexed functional data

- Providing educational outreach to ensure MAVE data accessibility and clinical uptake [2]

Major initiatives like the Atlas of Variant Effects (AVE) Alliance are working to systematize the clinical validation of functional assay data, though challenges remain in funding labor-intensive curation efforts and developing flexible approaches to assay validation [2].

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Advanced computational methods are increasingly important for VUS interpretation:

- Machine Learning Models: Decision trees, SVM, and random forests for structured data classification tasks

- Deep Learning Models: CNNs and RNNs for large-scale unstructured data, though requiring substantial computational resources

- Mathematical Modeling: Equations and algorithms to simulate medical outcomes and biological behavior, with approximately 21% of recent medical manuscripts utilizing mathematical modeling approaches [1]

These computational approaches are particularly valuable for interpreting the functional impact of non-coding variants, which constitute over 90% of genome-wide association study variants for common diseases but remain challenging to assess [6].

The resolution of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) represents a critical challenge in modern genomic medicine, with significant implications for patient diagnosis, risk assessment, and clinical management. Recent advances in single-cell multi-omics, multiplexed functional assays, and updated classification frameworks are substantially improving our ability to resolve these ambiguous variants. The development of international standards through initiatives like the AVE Alliance and implementation of quantitative, Bayesian-informed approaches to variant classification are further accelerating progress in this field.

As these technologies and frameworks continue to evolve, they promise to reduce diagnostic odysseys for patients with rare diseases, improve equity in genomic medicine across diverse populations, and ultimately enhance the clinical utility of genetic testing across a broad spectrum of human diseases.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized molecular diagnostics, providing an unparalleled capacity to detect millions of genetic variants rapidly and cost-effectively [9]. This technology has transformed disease diagnosis, particularly in oncology and rare genetic disorders, by moving beyond single-gene tests to comprehensive multigene analysis and whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing [9] [10]. However, a critical diagnostic limitation persists: the detection of a genetic variant does not automatically elucidate its functional or pathological significance. The vast majority of variants identified through NGS are classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), creating profound challenges for clinical interpretation and patient management [11]. This application note examines the inherent limitations of NGS-based identification and establishes why functional validation represents an indispensable next step for translating genomic findings into clinically actionable insights, particularly within the context of drug development and personalized therapeutic strategies.

Table 1: Core Limitations of NGS in Clinical Diagnostics

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Diagnostic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Classification | High rate of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) | Inconclusive test results, preventing definitive diagnosis and management [11] |

| Technical Constraints | Short-read limitations in complex genomic regions | Incomplete or inaccurate variant calling in repetitive, homologous, or structurally complex areas [9] |

| Contextual Interpretation | Inability to determine variant impact on protein function | Known variants may be detected, but their pathological effect on gene/protein activity remains unknown [11] |

| Data Integration | Lack of robust, validated functional databases | Difficulties in matching novel variants to established phenotypic patterns without functional correlates [12] |

Key Limitations of NGS in Clinical Diagnostics

The Challenge of Variant Interpretation and VUS

The primary challenge in clinical NGS application lies not in variant detection, but in biological interpretation. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) have established guidelines for variant classification, which include criteria for functional evidence [11]. Despite this framework, differences in the application of functional evidence codes (PS3/BS3) remain a significant source of discordance between laboratories [11]. The fundamental issue is that NGS identifies sequence changes but cannot discern whether those changes are pathogenic, benign, or functionally neutral without additional evidence. This diagnostic uncertainty directly impacts patient care, as clinicians cannot base definitive treatment or surveillance strategies on VUS findings.

Technical and Analytical Constraints

NGS technologies, particularly dominant short-read platforms, face inherent technical limitations that affect diagnostic comprehensiveness. Short-read sequencing (50-600 base pairs) struggles with complex genomic regions containing repetitive sequences, paralogous genes, or structural variations [9]. These limitations can lead to ambiguous mapping, coverage gaps, and false positives/negatives in variant calling. While long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., SMRT, Nanopore) address some of these issues by generating reads thousands of base pairs long, they have historically faced higher error rates and are not yet the clinical standard [9]. Furthermore, NGS assays require complex bioinformatic pipelines for data analysis, and variations in these pipelines, coupled with a lack of standardized validation approaches across laboratories, can lead to inconsistent results [12].

The Critical Role of Functional Validation

Functional validation moves beyond sequence observation to experimentally determine the biochemical consequences of a genetic variant. It bridges the gap between variant identification and understanding its role in disease pathogenesis.

Establishing a Framework for Functional Evidence

The ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Working Group has developed a refined, structured framework for evaluating functional data for clinical variant interpretation [11]. This framework provides critical guidance for applying the PS3/BS3 evidence codes and involves a four-step process:

- Define the disease mechanism (e.g., loss-of-function, gain-of-function).

- Evaluate the applicability of general classes of assays used in the field.

- Evaluate the validity of specific assay instances, including design, controls, and statistical rigor.

- Apply evidence to individual variant interpretation.

This process emphasizes that a "well-established" functional assay must be robustly validated with a sufficient number of known pathogenic and benign control variants to demonstrate its predictive power. It is estimated that a minimum of 11 total pathogenic and benign variant controls are required to achieve moderate-level evidence in the absence of rigorous statistical analysis [11].

Integrated Approaches for Variant Resolution

Cutting-edge research now combines NGS with advanced computational and experimental methods to resolve VUS. For example, a 2025 study on Colombian colorectal cancer patients integrated NGS with artificial intelligence to identify pathogenic germline variants [10]. The researchers used the BoostDM AI model to identify oncodriver germline variants with potential implications for disease progression, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.803 for the genes in their panel, demonstrating high predictive accuracy [10]. This highlights how AI can prioritize variants for functional testing. Furthermore, for non-coding or splice-site variants, the same study employed minigene assays for functional validation, which successfully revealed the generation of aberrant transcripts, thereby clarifying the molecular etiology of the disease [10]. The integration of NGS, AI, and functional assays represents a powerful, multi-faceted approach to overcoming the diagnostic limitations of NGS alone.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Validation

Protocol: Saturation Genome Editing (SGE) for Functional Variant Assessment

Saturation Genome Editing (SGE) is a high-throughput method that uses CRISPR-Cas9 and homology-directed repair (HDR) to introduce exhaustive nucleotide modifications at a specific genomic locus, enabling the functional assessment of nearly all possible variants in a gene while preserving their native genomic context [13].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Saturation Genome Editing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| HAP1-A5 Cells | Near-haploid human cell line that facilitates the functional study of recessive alleles [13]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | RNA-guided genome editing system comprising Cas9 nuclease and single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for targeted DNA cleavage. |

| Variant Library | A complex pool of DNA templates (donor oligos) designed to introduce every possible single nucleotide variant or amino acid substitution in the target exon. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Reagents for preparing sequencing libraries from the amplified target region post-selection to determine variant frequencies. |

Detailed Methodology:

Library and sgRNA Design:

- Design a library of donor oligonucleotides encompassing all possible nucleotide substitutions at the target genomic region(s).

- Design and validate a highly efficient sgRNA that cleaves adjacent to the target site for efficient HDR.

Cell Transduction and Editing:

- Transduce HAP1-A5 cells with the Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex and the variant library donor templates.

- Allow time for HDR-mediated integration of the variant library into the native genomic locus.

Selection and Harvest:

- Apply a functional selection pressure that enriches for cells with wild-type (or mutant) protein activity, or use a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based assay to separate cell populations based on phenotype.

- Harvest genomic DNA from the pre-selection population and the post-selection population(s).

NGS Library Preparation and Analysis:

- Amplify the target genomic region from all population samples via PCR and prepare NGS libraries.

- Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput NGS platform.

- Quantify the abundance of each variant in the pre- and post-selection samples. A significant depletion of a variant after selection indicates a deleterious functional impact.

The workflow for this functional validation protocol is systematic and high-throughput, as illustrated below:

Protocol: Minigene Splicing Assay for Intronic Variants

The minigene assay is a powerful method to experimentally determine the impact of intronic or exonic variants on mRNA splicing, a common disease mechanism that is often difficult to predict computationally.

Detailed Methodology:

Vector and Construct Design:

- Clone a genomic fragment of interest (containing the exon with its flanking intronic sequences, including the variant under investigation) into an exon-trapping vector (e.g., pSPL3).

- Create two constructs: one with the wild-type sequence and one with the patient-derived mutant sequence.

Cell Transfection and RNA Harvest:

- Transfect the wild-type and mutant minigene constructs into a suitable mammalian cell line (e.g., HEK293T).

- Incubate for 24-48 hours to allow for transcription and splicing.

- Harvest total RNA from the transfected cells and perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA.

PCR and Analysis:

- Amplify the cDNA using vector-specific primers that flank the cloned insert.

- Analyze the PCR products by gel electrophoresis. Splicing patterns will appear as bands of different sizes.

- Sequence the individual PCR bands to confirm the exact exon-intron structure and identify aberrant splicing events (e.g., exon skipping, intron retention, cryptic splice site usage).

The logical flow for validating splicing defects is as follows:

The diagnostic limitation of NGS is unequivocal: identification is not synonymous with understanding. To realize the full promise of precision medicine, the research and clinical diagnostics communities must adopt an integrated framework that couples comprehensive genomic sequencing with rigorous functional validation. The experimental protocols and frameworks outlined here, including SGE and minigene assays, provide a pathway to resolve VUS, refine clinical classifications, and generate biologically meaningful data. For drug development professionals, this integrated approach is particularly critical, as targeting a genetically defined patient population with a therapy requires high confidence in the pathogenicity of the targeted variant. Moving forward, the continued development, standardization, and implementation of high-throughput functional assays will be essential to bridge the gap between genomic discovery and actionable clinical insight, ultimately ensuring that NGS fulfills its potential as a transformative diagnostic tool.

The 2015 guidelines from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) established a standardized framework for interpreting sequence variants in Mendelian disorders [14]. Within this framework, functional studies represent a powerful form of evidence, categorized under the strong evidence codes PS3 and BS3. The PS3 code supports pathogenicity for "well-established" functional assays demonstrating a variant has abnormal gene/protein function, while BS3 supports benignity for assays showing normal function [15] [11].

Despite their potential, the original guidelines provided limited detailed guidance on how to evaluate functional assays, leading to significant inconsistencies in their application across clinical laboratories [15] [16] [11]. This document outlines structured protocols and application notes for implementing functional evidence criteria within the ACMG/AMP framework, providing researchers and clinicians with standardized approaches for assay validation and variant interpretation.

Theoretical Framework: Validating Functional Assays

The Four-Step Evaluation Framework

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Working Group developed a provisional four-step framework to determine the appropriate strength of evidence for functional assays [15] [11]. This systematic approach ensures that experimental data cited in clinical variant interpretation meets baseline quality standards.

Step 1: Define the disease mechanism - Precise understanding of the molecular basis of disease is foundational. This includes determining whether the disorder results from loss-of-function or gain-of-function mechanisms, the relevant protein domains and critical functional regions, and the appropriate model systems that recapitulate the disease biology [15] [11].

Step 2: Evaluate the applicability of general classes of assays - Researchers should assess how closely the assay reflects the biological environment, whether it captures the full spectrum of protein function, and the technical parameters including throughput, quantitative output, and dynamic range [15].

Step 3: Evaluate the validity of specific instances of assays - This involves rigorous validation of individual assay implementations through statistical analysis of performance metrics, inclusion of appropriate control variants, and demonstration of reproducibility across experimental replicates [15] [11].

Step 4: Apply evidence to individual variant interpretation - Finally, validated assays are applied to variant classification, with careful consideration of whether the evidence strength should be supporting, moderate, or strong based on the assay's validation data and performance characteristics [15].

Minimum Control Requirements for Evidence Strength

The stringency of evidence applied to functional data (supporting, moderate, or strong) depends heavily on the number and quality of control variants used during assay validation. The SVI Working Group performed quantitative analyses to establish minimum control requirements.

Table 1: Minimum Control Requirements for Functional Evidence Strength

| Evidence Strength | Minimum Control Variants | Pathogenic Controls | Benign Controls | Statistical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting | 6 total | ≥3 pathogenic | ≥3 benign | No rigorous statistical analysis required |

| Moderate | 11 total | ≥5 pathogenic | ≥5 benign | OR ≥3 with 95% CI ≥1.5 in case-control studies |

| Strong (PS3/BS3) | 18 total | ≥9 pathogenic | ≥9 benign | Robust statistical validation with high confidence intervals |

The SVI Working Group determined that a minimum of 11 total pathogenic and benign variant controls are required to reach moderate-level evidence in the absence of rigorous statistical analysis [15] [11]. For strong-level evidence (the traditional PS3/BS3 criteria), more extensive validation with approximately 18 well-characterized control variants is recommended [15].

Practical Implementation: Gene-Specific Specifications

PALB2 Case Study: Limitations on Functional Evidence

The Hereditary Breast, Ovarian and Pancreatic Cancer (HBOP) Variant Curation Expert Panel (VCEP) developed gene-specific specifications for PALB2, demonstrating how general ACMG/AMP guidelines require refinement for individual genes.

Table 2: PALB2-Specific Modifications to ACMG/AMP Functional Evidence Criteria

| ACMG/AMP Code | Original Definition | PALB2-Modified Application | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| PS3 | Well-established functional studies supportive of damaging effect | Not used for any variant type | Lack of known pathogenic missense variants for assay validation |

| BS3 | Well-established functional studies show no damaging effect | Not used for any variant type | Same rationale as PS3 |

| PM1 | Located in mutational hot spot/well-established functional domain | Not used | Missense pathogenic variation not confirmed as disease mechanism |

| BP4 | Multiple lines of computational evidence suggest no impact | Not used for missense variants | Supportive evidence only for in-frame indels/extension codes |

For PALB2, the HBOP VCEP recommended against using PS3, BS3, and several other codes entirely due to the lack of established pathogenic missense variants needed for functional assay validation [17]. This conservative approach highlights the critical importance of gene-disease mechanism understanding when applying functional evidence criteria.

Experimental Protocols for Validated Functional Assays

Splicing Assay Protocol

Purpose: To experimentally determine the impact of genomic variants on mRNA splicing patterns.

Methodology:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality RNA from patient-derived cells (lymphocytes, fibroblasts, or tissue-specific cell types) using commercial RNA extraction kits with DNase I treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- cDNA Synthesis: Perform reverse transcription using gene-specific primers or random hexamers with controls to ensure no genomic DNA amplification.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers spanning the exonic region of interest with appropriate positive and negative controls. Include samples from known pathogenic splice variants, benign controls, and wild-type references.

- Product Analysis: Separate PCR products by capillary electrophoresis or agarose gel electrophoresis; quantify aberrant vs. normal splicing ratios; confirm novel splice products by Sanger sequencing.

Interpretation Criteria: >10% aberrant splicing compared to wild-type constitutes abnormal splicing; <5% is considered within normal technical variation; results between 5-10% require additional supporting evidence [17].

Functional Complementation Assay Protocol

Purpose: To assess the functional impact of variants in DNA repair genes like PALB2 through rescue of DNA damage sensitivity.

Methodology:

- Cell Line Establishment: Use PALB2-deficient mammalian cell lines with demonstrated sensitivity to DNA damaging agents (e.g., mitomycin C).

- Vector Construction: Clone wild-type and variant PALB2 cDNA into mammalian expression vectors with selectable markers; verify sequence integrity.

- Transfection & Selection: Transfect PALB2-deficient cells with wild-type, variant, and empty vector controls; select stable pools or clones using appropriate antibiotics.

- Viability Assessment: Treat cells with increasing concentrations of DNA damaging agents; measure cell viability by MTT assay or colony formation after 5-7 days; normalize to untreated controls.

Interpretation Criteria: Variants demonstrating <20% of wild-type rescue activity are considered functionally abnormal; variants with >60% activity are considered functionally normal; intermediate values (20-60%) require additional evidence [17].

Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Assays

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | PALB2-deficient mammalian cells (e.g., EUFA1341), HEK293T, Patient-derived lymphoblastoids | Provide cellular context for functional complementation and splicing assays | Verify authenticity by STR profiling; monitor mycoplasma contamination |

| Expression Vectors | Mammalian cDNA expression vectors (e.g., pCMV6, pCDH), Minigene splicing constructs (e.g., pSPL3) | Express wild-type and variant sequences in cellular models | Include selectable markers; verify cloning by full insert sequencing |

| DNA Damage Agents | Mitomycin C, Olaparib, Cisplatin, Hydrogen Peroxide | Challenge DNA repair pathways to assess functional impact | Titrate concentrations carefully; include dose-response curves |

| Antibodies | PALB2-specific antibodies, BRCA2 antibodies for co-immunoprecipitation, Loading control antibodies (e.g., GAPDH, Tubulin) | Detect protein expression, localization, and interactions | Validate specificity using knockout cell lines; optimize dilution factors |

Data Integration and Evidence Synthesis

Integrating Functional Evidence with Other Data Types

Functional evidence should never be interpreted in isolation. The ACMG/AMP framework provides specific guidance on combining functional data with other evidence types to reach variant classifications.

The integration of functional evidence with clinical and genetic data follows specific rules within the ACMG/AMP framework. For example, functional data may be combined with population data (PM2/BS1), computational predictions (PP3/BP4), segregation data (PP1), and de novo observations (PS2) to strengthen variant classification [17] [14]. However, circular reasoning must be avoided—functional data should not be combined with the same patient's clinical data (PP4) if that clinical data was used to establish the assay's clinical validity [15].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite standardization efforts, significant challenges remain in the consistent application of functional evidence. A recent consultation identified several barriers to effective use of functional evidence in variant classification, including inaccessibility of published data, lack of standardization across assays, and difficulties in integrating functional data into clinical workflows [18].

Future directions focus on developing higher-throughput functional assays, creating centralized databases for functional data, and establishing more quantitative frameworks for evidence integration. Multiplex Assays of Variant Effect (MAVEs) show particular promise for systematically measuring the functional impact of thousands of variants in parallel [18].

The evolution of functional evidence application continues, with the recent retirement of the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group in April 2025 and the transition to consolidated variant classification guidance [19]. This transition represents the maturation of variant interpretation standards and the integration of functional evidence into mainstream clinical practice.

Functional evidence remains a powerful component of variant classification within the ACMG/AMP framework when applied systematically and with appropriate validation. The protocols and specifications outlined here provide researchers and clinical laboratories with standardized approaches for implementing functional evidence criteria, ultimately leading to more consistent and accurate variant interpretation across the genetics community. As functional technologies continue to evolve, these guidelines will require ongoing refinement to incorporate new assay methodologies and expanding validation datasets.

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has revolutionized molecular genetics, enabling the rapid identification of millions of genetic variants. However, a significant bottleneck has emerged in distinguishing causal disease variants from benign background variation. Functional genomics addresses this challenge by moving beyond correlation to establish causation, providing the experimental evidence needed to determine the pathological impact of genetic variants. In the clinical interpretation of variants identified through whole exome or whole genome sequencing (WES/WGS), the majority fall into the category of "variants of unknown significance" (VUS), creating uncertainty for diagnosis and treatment [20]. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) has established the PS3/BS3 criterion as strong evidence for variant classification, but differences in applying these functional evidence codes have contributed to interpretation discordance between laboratories [11]. This framework outlines standardized approaches for functional validation of genetic variants, providing researchers with clear protocols to bridge the gap between variant discovery and clinical application.

Quantitative Landscape of Functional Genomics

Outcomes from Genomic Sequencing Studies

Table 1: Distribution of Possible Outcomes from WES/WGS Analyses

| Outcome Number | Variant Type | Gene Association | Phenotype Match | Diagnostic Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Known disease-causing variant | Known disease gene | Matching | Definitive diagnosis |

| 2 | Unknown variant | Known disease gene | Matching | Likely diagnosis (requires validation) |

| 3 | Known variant | Known disease gene | Non-matching | Uncertain significance |

| 4 | Unknown variant | Known disease gene | Non-matching | Uncertain significance |

| 5 | Unknown variant | Gene not associated with disease | Unknown | Uncertain significance |

| 6 | No explanatory variant found | N/A | N/A | No diagnosis |

Current data indicates that in the majority of investigations (approximately 60-75%), WES or WGS does not yield a definitive genetic diagnosis, primarily due to the challenge of VUS interpretation [20]. The success of functional genomics lies in its ability to reclassify these VUS into definitive diagnostic categories.

Evidence Thresholds for Functional Validation

Table 2: Control Requirements for Functional Assay Evidence Strength

| Evidence Strength | Minimum Pathogenic Controls | Minimum Benign Controls | Total Variant Controls | Statistical Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting | 2 | 2 | 4 | Not required |

| Moderate | 5 | 6 | 11 | Not required |

| Strong | 8 | 9 | 17 | Not required |

| Very Strong | 12 | 13 | 25 | Not required |

The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group has established these minimum control requirements to standardize the application of the PS3/BS3 ACMG/AMP criterion [11]. These thresholds ensure that functional evidence meets a baseline quality level before being applied in clinical variant interpretation.

Advanced Methodologies in Functional Genomics

Single-Cell DNA–RNA Sequencing (SDR-seq)

Protocol: SDR-seq for Functional Phenotyping of Genomic Variants

Principle: SDR-seq simultaneously profiles genomic DNA loci and gene expression in thousands of single cells, enabling accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated transcriptional changes [6].

Workflow:

Cell Preparation:

- Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension.

- Fix cells using paraformaldehyde (PFA) or glyoxal (glyoxal is preferred for reduced nucleic acid cross-linking).

- Permeabilize cells to allow reagent entry.

In Situ Reverse Transcription:

- Perform reverse transcription using custom poly(dT) primers.

- Primers add a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI), sample barcode, and capture sequence to cDNA molecules.

Droplet Generation and Lysis:

- Load cells onto microfluidic platform (e.g., Tapestri from Mission Bio).

- Generate first droplet emulsion.

- Lyse cells within droplets using proteinase K treatment.

Multiplexed PCR Amplification:

- Mix cell lysate with reverse primers for each gDNA and RNA target.

- Generate second droplet containing forward primers with capture sequence overhang, PCR reagents, and barcoding beads with cell barcode oligonucleotides.

- Perform multiplexed PCR to co-amplify gDNA and RNA targets.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Break emulsions and pool amplification products.

- Use distinct overhangs on gDNA (R2N) and RNA (R2) reverse primers to separate and prepare NGS libraries.

- Sequence gDNA libraries for full-length variant information and RNA libraries for transcript expression quantification.

Validation: In proof-of-concept experiments, SDR-seq detected 82% of gDNA targets (23 of 28) with high coverage across the majority of cells, while RNA targets showed varying expression levels consistent with expected patterns [6]. The method demonstrates minimal cross-contamination (<0.16% for gDNA, 0.8-1.6% for RNA) and scales effectively to panels of 480 simultaneous targets.

CRISPR Editing and Transcriptomic Profiling

Protocol: Functional Validation of VUS Using CRISPR in Cell Models

Principle: Introduction of specific VUS into cell lines using CRISPR-Cas9 followed by genome-wide transcriptomic profiling to identify disease-relevant pathway disruptions [21].

Workflow:

Guide RNA Design and Synthesis:

- Design sgRNAs flanking the genomic location of the VUS.

- Include homologous repair templates containing the specific nucleotide change.

- Synthesize and validate sgRNAs and repair templates.

Cell Transfection and Selection:

- Transfect HEK293T or other relevant cell lines with Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes and repair templates.

- Apply antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) 48 hours post-transfection.

- Isolate single-cell clones by serial dilution or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

Genotype Validation:

- Expand single-cell clones for 2-3 weeks.

- Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR amplification of the target region.

- Confirm precise editing via Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing.

Functional Phenotyping:

- Passage validated clones and analyze using RNA-seq for transcriptomic profiling.

- Process RNA-seq data through bioinformatic pipelines for quality control, alignment, and differential expression analysis.

- Perform gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and pathway analysis to identify disrupted biological processes.

Data Integration:

- Compare expression profiles to known disease signatures.

- Corrogate pathway disruptions with clinical disease phenotypes.

Application: In a proof-of-concept study introducing an EHMT1 variant into HEK293T cells, this approach identified changes in cell cycle regulation, neural gene expression, and chromosome-specific expression suppression consistent with Kleefstra syndrome phenotypes [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Functional Genomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, Prime Editing | Precise introduction of genetic variants into cellular models or model organisms. |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics, Tapestri Mission Bio | High-throughput single-cell analysis enabling simultaneous DNA and RNA profiling. |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina Nextera, TruSeq | Library preparation for next-generation sequencing of genomic DNA and transcriptomes. |

| Cell Culture Models | HEK293T, iPSCs, Primary cells | Cellular context for evaluating variant effects in relevant biological systems. |

| Fixation Agents | Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Glyoxal | Cell fixation and permeabilization for nucleic acid preservation in single-cell assays. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | GATK, Seurat, DTOM | Data analysis pipelines for variant calling, single-cell analysis, and causal inference. |

Analytical Framework for Functional Evidence

Causal Discovery Using Directed Topological Overlap Matrix (DTOM)

Principle: Moving beyond correlation analysis, DTOM provides a more flexible approach to causal discovery that is robust to measurement errors, averaging effects, and feedback loops [22]. This method relaxes the local causal Markov condition and uses Reichenbach's common cause principle instead, providing significant improvements in sample efficiency.

Application: DTOM has demonstrated utility in distinguishing myostatin mutation status in cattle based on muscle transcriptomes, identifying deleted genes in yeast deletion studies using differentially expressed gene sets, and elucidating causal genes in Alzheimer's disease progression [22].

Four-Step Framework for Functional Evidence Evaluation

The ClinGen SVI Working Group recommends a structured approach for assessing functional assays:

Define Disease Mechanism: Establish the expected molecular consequence of pathogenic variants (e.g., loss-of-function, gain-of-function, dominant-negative).

Evaluate General Assay Classes: Determine which general classes of assays (e.g., splicing, enzymatic, protein localization, transcriptional activation) are appropriate for the disease mechanism.

Validate Specific Assay Instances: Assess the technical validation of specific assay implementations using established control requirements and performance metrics.

Apply to Variant Interpretation: Assign appropriate evidence strength based on assay validation and result concordance with expected functional impact.

This framework ensures functional data meets baseline quality standards before application in clinical variant interpretation [11].

Functional genomics represents the essential bridge between variant detection and clinical application, providing the causal evidence required to move from correlation to causation. The methodologies outlined here—from single-cell multi-omics to CRISPR-based functional phenotyping and advanced causal inference algorithms—provide researchers with standardized approaches for variant interpretation. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will increasingly enable the resolution of variants of unknown significance, ultimately improving diagnostic yields and advancing personalized medicine approaches for rare and common genetic diseases. The future of functional genomics lies in the continued development of scalable, quantitative assays that can be systematically validated and standardized across laboratories, ultimately benefiting patients through more accurate genetic diagnoses.

A Toolkit for Validation: From Bench Assays to Bioinformatics

Cell-based assays are indispensable tools in functional genomics and immunology, enabling researchers to connect genetic findings to phenotypic outcomes. In the context of validating genetic variants in immune dysfunction disorders, assays that probe specific cellular signaling pathways and effector functions are particularly valuable. This application note details two essential methodologies: the Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) AlphaLISA assay for interrogating JAK/STAT signaling pathway integrity, and the Dihydrorhodamine (DHR) assay for assessing phagocytic function in Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD). These assays provide critical functional data that can help determine the pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in immunologically relevant genes, bridging the gap between genomic sequencing and clinical manifestation [23].

The integration of such functional assays is becoming increasingly important as genomic studies reveal numerous VUS whose clinical significance remains ambiguous. Without functional validation, these variants pose challenges for genetic counseling and personalized treatment strategies [23]. The pSTAT1 and DHR assays described herein offer robust, quantitative approaches to characterize immune dysfunction at the cellular level, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic avenues.

Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) Assay for JAK/STAT Signaling Assessment

Background and Principle

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 (STAT1) is a crucial transcription factor in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, playing a central role in mediating interferon responses, immune regulation, and cell growth control [24]. Activation of STAT1 occurs through phosphorylation at tyrosine residue 701 (Tyr701), which is essential for STAT1 dimerization, nuclear translocation, and subsequent transcriptional activity [24]. Dysregulation of STAT1 signaling is implicated in various pathological conditions, including recent findings that the EGFR-STAT1 pathway drives fibrosis initiation in fibroinflammatory skin diseases [25]. This pathway represents a novel interferon-independent function of STAT1 in mediating fibrotic skin conditions [25].

The AlphaLISA SureFire Ultra Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) assay is a sandwich immunoassay that enables quantitative detection of phosphorylated STAT1 in cellular lysates using Alpha technology [24]. This homogeneous, no-wash assay is particularly suitable for research investigating immune signaling dysregulation potentially stemming from genetic variants in STAT1 or related pathway components.

Detailed Protocol

Cell Culture and Treatment

- Cell Preparation: Plate appropriate cells (e.g., THP-1 cells, primary macrophages, or patient-derived cells) in complete medium. For THP-1 cells, seed at 100,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate containing 100 nM PMA and incubate for 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ to differentiate into macrophages [24].

- Serum Starvation: Replace medium with starvation medium (e.g., HBSS + 0.1% BSA) for 2 hours to minimize basal signaling activity.

- Stimulation: Treat cells with IFNγ (typically 0.1-100 ng/mL) or other relevant stimuli for 15-20 minutes to induce STAT1 phosphorylation. Include appropriate controls (unstimulated and maximum stimulation).

Cell Lysis

- Immediately after stimulation, remove treatment medium and lyse cells with recommended Lysis Buffer (e.g., 60-150 μL depending on cell density) for 10 minutes at room temperature with shaking at 350 rpm [24].

- Note: The lysates can be used immediately or stored at -80°C for future analysis.

Detection Procedure

- Transfer 10 μL of cell lysate to a 384-well white OptiPlate.

- Add 5 μL of Acceptor Mix and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Add 5 μL of Donor Mix and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Read the plate using an EnVision or compatible plate reader with standard AlphaLISA settings.

Assay Validation Data

The Phospho-STAT1 assay demonstrates robust performance characteristics as validated in multiple cell models:

Table 1: Validation data for Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) AlphaLISA assay

| Cell Type | Stimulus | EC₅₀ | Dynamic Range | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary human macrophages | IFNα | ~1-10 ng/mL | >100-fold | Dose-dependent phosphorylation; specific for pSTAT1 without affecting total STAT1 [24] |

| Primary human macrophages | IFNγ | ~0.1-10 ng/mL | >100-fold | Strong phosphorylation response; pathway specificity confirmed [24] |

| THP-1-derived macrophages | IFNγ | ~0.1-10 ng/mL | >50-fold | Reproducible dose response; minimal inter-assay variability [24] |

| RAW 264.7 mouse macrophages | Mouse IFNγ | ~0.1-10 ng/mL | >50-fold | Cross-species reactivity confirmed; similar performance in mouse cells [24] |

Research Applications in Functional Genomics

The pSTAT1 assay provides critical functional data for evaluating variants in STAT1 and related pathway genes. Recent research has highlighted the importance of STAT1 in fibroinflammatory skin diseases, where single-cell RNA sequencing analysis revealed that STAT1 is the most significantly upregulated transcription factor in SFRP2+ profibrotic fibroblasts across multiple fibroinflammatory conditions [25]. This assay can help determine whether genetic variants affect STAT1 phosphorylation kinetics, magnitude, or duration, thereby establishing potential pathogenicity.

Furthermore, the discovery that EGFR can directly activate STAT1 in a JAK-independent manner in fibrotic skin diseases [25] opens new avenues for investigating crosstalk between signaling pathways that may be disrupted by genetic variants. This assay can be adapted to test activation by alternative stimuli beyond interferons, including EGF family ligands.

DHR Assay for Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) Diagnosis

Background and Principle

Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) is an inherited phagocytic disorder characterized by recurrent, life-threatening pyogenic infections and granulomatous inflammation. The disease arises from defects in the phagocytic nicotinamide dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase complex, resulting in reduced or absent production of microbicidal reactive oxygen species (ROS) during phagocytosis [26]. The DHR assay indirectly measures ROS production by monitoring the oxidation of dihydrorhodamine 123 to its fluorescent form, rhodamine, providing a robust flow cytometry-based screening method for CGD [26].

The NADPH oxidase complex consists of five subunit proteins: two membrane components (gp91phox, p22phox) and three cytosolic components (p47phox, p67phox, p40phox). Genetic defects in any of these components can cause CGD, with approximately 60% of cases resulting from X-linked mutations in the CYBB gene encoding gp91phox, and 30% from autosomal recessive mutations in the NCF1 gene encoding p47phox [26]. The DHR assay can detect CGD patients, carriers, and can suggest the underlying genotype based on the pattern of oxidative activity.

Detailed Protocol

Reagent Preparation

- DHR123 Stock Solution: Prepare at 2500 μg/mL in DMSO. Aliquot into 35 μL volumes and store at -20°C.

- PMA Stock Solution: Prepare at 100 μg/mL in DMSO. Aliquot into 30 μL volumes and store at -20°C.

- Working Solutions: On the day of assay, prepare DHR123 working solution at 15 μg/mL and PMA working solution at 300 ng/mL in phosphate-buffered saline with azide (PBA).

Sample Preparation and Staining

- Collect fresh heparinized blood and dilute 1:10 with PBA.

- Set up three tubes for each patient and control:

- Unstained Control: 100 μL diluted blood

- DHR-Loaded Control: 100 μL diluted blood + 25 μL DHR123 working solution

- Stimulated Test: 100 μL diluted blood + 25 μL DHR123 working solution + 100 μL PMA working solution

- Incubate all tubes in a 37°C water bath for 15 minutes to load DHR123.

- Add PMA to tube 3 only and incubate all tubes for an additional 15 minutes at 37°C.

Sample Processing and Analysis

- Wash samples with PBS and centrifuge.

- Lyse red blood cells using ammonium chloride solution (e.g., Pharm Lyse) for 10 minutes in the dark.

- Wash, centrifuge, and fix cells in 1% formalin.

- Analyze by flow cytometry using the 488nm laser and FITC filter set.

- Gate on neutrophil population based on FSC vs SSC characteristics.

- Calculate Neutrophil Oxidative Index (NOI) as the ratio of mean peak channel fluorescence (MPC-FL) of PMA-stimulated samples to unstimulated samples.

Assay Performance and Interpretation

The DHR assay demonstrates distinct fluorescence patterns that correlate with CGD subtype and severity:

Table 2: DHR assay interpretation guide for CGD diagnosis

| Pattern | NOI Range | Histogram Profile | Possible Genotype | Carrier Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | >100 (typically 1000+) | Sharp, unimodal peak | Normal | Not applicable |

| X-linked CGD (severe) | 1-2 | Completely flat | CYBB null mutation | Bimodal distribution (mosaic pattern) |

| X-linked CGD (moderate) | 3-50 | Broad, low peak | CYBB hypomorphic mutation | Partial bimodal distribution |

| p47phox-deficient CGD | 3-50 | Broad, low peak | NCF1 mutation | Not typically detectable (autosomal recessive) |

| Other AR CGD (p22phox, p67phox) | 1-50 | Variable | CYBA, NCF2 mutations | Not typically detectable (autosomal recessive) |

Recent advancements include the development of a DHR-ELISA method that offers a rapid, cost-effective alternative for CGD screening, particularly in resource-limited settings. This method demonstrated 90% specificity and 90.5-100% sensitivity in detecting CGD compared to genetic testing [27].

Research Applications in Functional Genomics

The DHR assay serves as a crucial functional validation tool for variants in NADPH oxidase complex genes. With the expanding use of next-generation sequencing, numerous VUS are being identified in CGD-associated genes. The DHR assay provides a direct measurement of the functional consequences of these variants on phagocyte function.

In a recent study of 72 children suspected of having CGD, genetic testing revealed mutations in CYBB (71.0%), NCF1 (15.8%), CYBA (7.9%), and NCF2 (5.3%) genes [27]. The DHR assay confirmed the functional impact of these mutations, with patients showing significantly reduced enzymatic activity compared to healthy controls. This integration of genetic and functional analysis provides a comprehensive diagnostic approach and helps establish pathogenicity for novel variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and resources for pSTAT1 and DHR assays

| Category | Specific Product | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSTAT1 Detection | AlphaLISA SureFire Ultra Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) Detection Kit [24] | Quantifying STAT1 phosphorylation | Homogeneous, no-wash assay; 10 μL sample volume; compatible with cell lysates |

| Cell Stimulation | Recombinant Human IFNγ | STAT1 pathway activation | High-purity; dose-dependent response (0.1-100 ng/mL) |

| DHR Assay | Dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) [26] | Measuring oxidative burst in phagocytes | Oxidation to fluorescent rhodamine; 375 ng/mL final concentration |

| DHR Stimulation | Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) [26] | Activating NADPH oxidase complex | Potent PKC activator; 30 ng/mL final concentration |

| DHR Alternative | DHR-ELISA method [27] | CGD screening without flow cytometry | 90% specificity, 90.5-100% sensitivity; cost-effective |

| Advanced Genomics | Single-cell DNA-RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) [6] | Linking genotypes to cellular phenotypes | Simultaneous profiling of 480 genomic DNA loci and genes in single cells |

Experimental Workflows

pSTAT1 Assay Workflow

DHR Assay Workflow

STAT1 Signaling Pathway

The pSTAT1 and DHR assays represent powerful approaches for functionally validating genetic variants associated with immune dysfunction. The pSTAT1 assay provides insights into signaling pathway integrity, with recent research revealing its importance in both canonical interferon signaling and novel pathways such as EGFR-mediated fibrosis [25]. Meanwhile, the DHR assay offers a direct measurement of phagocyte function, essential for diagnosing CGD and validating variants in NADPH oxidase complex genes [26].

These assays bridge the critical gap between genetic identification and functional consequence, enabling researchers to establish pathogenicity for VUS in immunologically relevant genes. As functional genomics advances, integration of such cell-based assays with emerging technologies like single-cell multi-omics [6] will enhance our ability to dissect the mechanistic consequences of genetic variation in immune disorders, ultimately advancing both diagnostic capabilities and therapeutic development.

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized functional genomics by enabling precise genetic modifications in a wide range of cell types and organisms. For researchers investigating the functional validation of genetic variants, CRISPR-mediated knock-in and knock-out studies provide powerful tools to establish causal relationships between genetic alterations and phenotypic outcomes. These techniques are particularly valuable in disease modeling, drug target validation, and elucidating mechanisms underlying pathological conditions [28] [29].

The fundamental principle involves using a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to specific genomic locations, creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are subsequently repaired by cellular mechanisms. While non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) typically results in gene knock-outs through insertions or deletions (indels), homology-directed repair (HDR) enables precise knock-ins using donor DNA templates [28] [29]. Understanding and controlling these repair pathways is essential for successful functional studies of genetic variants.

Fundamental Principles of CRISPR Knock-in/Knock-out

Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Repair Pathways

The cellular response to CRISPR-induced DSBs determines the editing outcome. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is an error-prone repair pathway active throughout the cell cycle, resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that often disrupt gene function—making it ideal for knock-out studies [28] [29]. In contrast, homology-directed repair (HDR) uses a donor DNA template for precise repair and is restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, enabling precise knock-in modifications [28].

Recent research reveals that DNA repair pathways differ significantly between cell types. Dividing cells such as iPSCs utilize both NHEJ and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), producing a broad range of indel outcomes. Conversely, postmitotic cells like neurons and cardiomyocytes predominantly employ classical NHEJ, resulting primarily in smaller indels, and exhibit prolonged DSB resolution timelines extending up to two weeks [30].

Advanced CRISPR Systems

Beyond standard CRISPR-Cas9, several advanced systems have expanded gene-editing capabilities:

- Base editing enables direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without inducing DSBs, using fusion proteins comprising a catalytically impaired Cas9 and a deaminase enzyme. Cytidine base editors (CBEs) convert C•G to T•A base pairs, while adenine base editors (ABEs) convert A•T to G•C base pairs [29].

- Prime editing offers greater versatility by using a Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site without DSB formation [29].

- Artificial intelligence-designed editors represent the cutting edge, with models like OpenCRISPR-1 showing comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being highly divergent in sequence [31].

Experimental Design and Optimization

gRNA Design and Validation

Effective gRNA design is critical for successful knock-in/knock-out experiments. sgRNAs consist of a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence defining the target site and a scaffold sequence for Cas9 binding. The target site must be immediately adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM); for the most commonly used SpCas9, this is 5'-NGG-3' [28].

Comparative analyses of gRNA design tools indicate that Benchling provides the most accurate predictions of editing efficiency [32]. However, computational predictions require experimental validation, as some sgRNAs with high predicted scores may be ineffective—for instance, an sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 exhibited 80% INDELs but retained ACE2 protein expression [32].

Validation methods include:

- T7 endonuclease I (T7EI) assay detects mismatches in heteroduplex DNA formed by annealing wild-type and edited sequences [33]

- Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) analyzes Sanger sequencing chromatograms to quantify editing efficiencies [32]

- Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) provides similar functionality with demonstrated accuracy against clonal sequencing data [32]

- Cleavage assay (CA) exploits the inability of Cas9-gRNA complexes to recognize and cleave successfully edited target sites [33]

Enhancing Knock-in Efficiency

HDR-mediated knock-in efficiency is typically lower than NHEJ-mediated knock-out due to cell cycle dependence and pathway competition. The following table summarizes key optimization parameters for both knock-in and knock-out studies:

Table 1: Optimization Parameters for CRISPR-mediated Knock-in and Knock-out Studies

| Parameter | Knock-out Optimization | Knock-in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Repair | Favor NHEJ | Suppress NHEJ, enhance HDR |

| Template Design | Not applicable | ssODN: 30-60nt arms; plasmid: 200-500nt arms |

| Cell Cycle | Effective in all phases | Maximize S/G2 populations |

| Delivery Method | RNP electroporation [32] | RNP + HDR template co-delivery |

| Validation | INDEL efficiency ≥80% [32] | HDR efficiency + protein validation |

Strategies to enhance HDR efficiency include:

- HDR template design: For short insertions using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), 30-60 nucleotide homology arms are recommended. For larger insertions requiring plasmid templates, 200-500 nucleotide homology arms yield optimal results [28].

- Cell cycle synchronization: Enriching for S/G2 phase populations increases HDR efficiency [28].

- Strategic insertion placement: Incorporating edits within 5-10 base pairs of the cut site minimizes strand preference effects. For edits outside this window, the targeting strand is preferred for PAM-proximal edits, while the non-targeting strand benefits PAM-distal edits [28].

- Modulating DNA repair: Small molecule inhibitors targeting NHEJ components can enhance HDR efficiency in some cell types [30].

Applications in Disease Research

Cancer Biology and Immunotherapy

CRISPR knock-out screens have identified essential genes in various cancers. For example, a genome-wide screen in metastatic uveal melanoma identified SETDB1 as essential for cancer cell survival, with its knockout inducing DNA damage, senescence, and proliferation arrest [34]. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), CRISPR knock-in approaches model specific mutations found in ABC and GCB subtypes to study their impacts on B-cell receptor signaling and NF-κB pathway activation [28].

In cancer immunotherapy, CRISPR-engineered CAR-T cells with knocked-out PTPN2 show enhanced signaling, expansion, and cytotoxicity against solid tumors in mouse models. PTPN2 deficiency promotes generation of long-lived stem cell memory CAR T cells with improved persistence [34].

Genetic Disorders

CRISPR editing shows remarkable therapeutic potential for genetic diseases. Prime editing has achieved 60% efficiency in correcting pathogenic COL17A1 variants causing junctional epidermolysis bullosa, with corrected cells demonstrating a selective advantage in xenograft models [34]. For sickle cell disease, base editing of hematopoietic stem cells outperformed conventional CRISPR-Cas9 in reducing red cell sickling, with higher editing efficiency and fewer genotoxicity concerns [34].

Functional Studies in B Cells

CRISPR knock-out screens enable systematic identification of genes regulating B-cell receptor (BCR) mediated antigen uptake. Using Ramos B-cells and genome-wide sgRNA libraries, researchers can identify genes whose disruption affects BCR internalization through flow cytometry-based sorting and sequencing of sgRNA abundances [35].

Table 2: Applications of CRISPR Knock-in/Knock-out in Disease Modeling

| Disease Area | Genetic Modification | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Uveal Melanoma | SETDB1 knockout [34] | DNA damage, senescence, halted proliferation |

| DLBCL | Oncogenic mutation knock-in [28] | Altered BCR signaling and NF-κB activation |

| Sickle Cell Disease | Base editing in HSPCs [34] | Reduced red cell sickling |

| Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa | COL17A1 prime editing [34] | Restored type XVII collagen expression |

| Solid Tumors | PTPN2 knockout in CAR-T cells [34] | Enhanced tumor infiltration and killing |

Protocols for Knock-in/Knock-out Studies

Protocol: Knock-out in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) Using Inducible Cas9

This optimized protocol achieves 82-93% INDEL efficiency in hPSCs [32]:

Materials:

- hPSCs with doxycycline-inducible Cas9 (hPSCs-iCas9)

- Chemically modified sgRNA (2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications)

- Nucleofection system (Lonza 4D-Nucleofector with P3 Primary Cell kit)

- Doxycycline

- Cell culture reagents

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Maintain hPSCs-iCas9 in Pluripotency Growth Medium on Matrigel-coated plates.

- Doxycycline Induction: Treat with doxycycline (concentration optimized for your cell line) for 24 hours to induce Cas9 expression.

- Cell Preparation: Dissociate cells with 0.5 mM EDTA and pellet by centrifugation at 250g for 5 minutes.

- Nucleofection: Combine 5μg sgRNA with nucleofection buffer and electroporate using program CA137.

- Repeat Transfection: After 3 days, repeat nucleofection with fresh sgRNA.

- Analysis: Harvest cells 5-7 days post-transfection for INDEL efficiency analysis by TIDE/ICE.

Troubleshooting:

- Low efficiency: Optimize cell-to-sgRNA ratio (8×10⁵ cells: 5μg sgRNA recommended)

- Poor viability: Ensure nucleofection program is appropriate for your hPSC line

- Incomplete knock-out: Verify sgRNA activity and consider dual sgRNAs

Protocol: Knock-in in Primary B Cells

This protocol addresses challenges of low HDR efficiency in primary human B cells [28]:

Materials:

- Primary human B cells or lymphoma cell lines

- Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNA

- HDR template (ssODN for point mutations, plasmid for large insertions)

- Electroporation system

- Culture media optimized for B cells

Procedure:

- gRNA Complex Formation: Precomplex Cas9 protein with sgRNA at 37°C for 10 minutes to form RNP.

- HDR Template Preparation: For point mutations, design ssODN with 30-60nt homology arms and symmetric extension around the mutation site.

- Cell Preparation: Enrich for cycling cells by pre-stimulation with CD40L and IL-4 for 48 hours to enhance HDR.

- Electroporation: Co-deliver RNP complex and HDR template using optimized electroporation conditions.

- Recovery and Analysis: Culture cells and assess knock-in efficiency after 72-96 hours by flow cytometry, sequencing, or functional assays.

Optimization Tips:

- Test multiple sgRNAs with varying distances to the target mutation

- Consider chemical inhibition of NHEJ to enhance HDR (e.g., KU-0060648)

- For large insertions (e.g., fluorescent proteins), use plasmid donors with 500nt homology arms

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Knock-in/Knock-out Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, OpenCRISPR-1 [31] | DSB induction at target sites |

| Base Editors | ABE8e, evoAPOBEC1-BE4max | Single nucleotide conversion without DSBs |

| Delivery Systems | LNPs [36], VLPs [30], Electroporation | Efficient cargo delivery to target cells |

| HDR Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA donors | Template for precise knock-in edits |

| gRNA Modifications | 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate [32] | Enhanced stability and editing efficiency |

| Validation Tools | ICE, TIDE, Cleavage Assay [33] | Quantification of editing outcomes |

| Cell Lines | hPSCs-iCas9 [32], Ramos B-cells [35] | Optimized platforms for editing studies |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, CRISPR knock-in/knock-out technologies face several challenges. Delivery efficiency remains a primary bottleneck, particularly for in vivo applications. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) show promise for liver-directed therapies but require optimization for other tissues [36]. Off-target effects continue to raise safety concerns, though AI-powered prediction tools are improving specificity assessments [31].

The DNA repair landscape in different cell types presents another hurdle, particularly for HDR-based approaches in non-dividing cells. Recent research reveals that neurons resolve Cas9-induced DSBs over weeks rather than days, with different repair pathway preferences compared to dividing cells [30]. Understanding these cell-type-specific differences is crucial for designing effective editing strategies.

Future directions include:

- AI-designed editors with enhanced properties [31]

- Epigenome editing for reversible gene regulation [34]

- Compact editing systems (e.g., Cas12f variants) compatible with viral delivery [34]

- In vivo delivery optimization through engineered LNPs and viral vectors

As the field advances, CRISPR knock-in/knock-out methodologies will continue to enhance our ability to functionally validate genetic variants, accelerating both basic research and therapeutic development.

The following diagrams provide visual summaries of key concepts and experimental workflows described in this application note.

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and DNA Repair Pathways

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Functional Validation

In the field of functional validation of genetic variants, one of the primary challenges is interpreting variants of unknown significance (VUS) discovered through next-generation sequencing. A conclusive diagnosis is crucial for patients, clinicians, and genetic counselors, requiring definitive evidence for pathogenicity [20]. Multi-omics corroboration represents a powerful approach to this challenge, integrating diverse biological data layers to validate molecular findings.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) coupled with protein-level biomarker profiling provides particularly compelling evidence for functional validation. This approach is revolutionizing molecular diagnostics by offering standardized quantitative assessment across multiple biomarkers in a single assay, overcoming limitations of traditional methods like immunohistochemistry (IHC) which can suffer from subjective interpretation and technical variability [37]. As we transition toward precision medicine, the integration of multi-omics data creates a comprehensive understanding of human health and disease by piecing together the "puzzle" of information across biological layers [38].

Experimental Rationale and Clinical Context

The Challenge of Variants of Unknown Significance

The introduction of whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) has revolutionized molecular genetics diagnostics, yet in the majority of investigations, these approaches do not result in a genetic diagnosis [20]. When variants are identified, they often fall into the uncertain significance category, requiring functional validation to determine their pathological impact.

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) has established five criteria regarded as strong indicators of pathogenicity, one of which is "established functional studies show a deleterious effect" [20]. Multi-omics approaches directly address this criterion by providing experimental evidence across multiple biological layers.

Advantages of Multi-Omics Corroboration

RNA-seq offers significant advantages for biomarker assessment compared to traditional methods:

- Objective quantification that circumvents inter-observer variability

- Multiplexing capability to evaluate numerous biomarkers simultaneously

- Standardized analysis across different laboratories and sample types

- High-throughput processing suitable for large-scale studies [37]

For clinical diagnostics, RNA-seq can serve as a robust complementary tool to IHC, offering particularly valuable insights when tumor microenvironment factors or sample quality issues affect protein-based assessments [37].

Experimental Protocols

RNA Sequencing for Biomarker Detection

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- Sample Types: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks or fresh-frozen (FF) tissue specimens

- Tissue Requirements: Minimum neoplastic cellularity of 20% as confirmed by pathologist review of H&E slides

- RNA Extraction: Use RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) for FFPE samples or AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit for fresh-frozen tissues

- Quality Assessment: Verify RNA integrity number (RIN) >7.0 for optimal sequencing results [37]

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Kits: Utilize SureSelect XT HS2 RNA kit (Agilent Technologies) with SureSelect Human All Exon V7 + UTR exome probe set for FFPE samples; TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep for fresh-frozen tissues

- Sequencing Parameters: Sequence on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) as paired-end reads (2 × 150 bp) with targeted coverage of 50 million reads per sample

- Processing: Align reads using Kallisto (version 0.42.4) with index file consistent with TCGA expression data [37]

Immunohistochemistry Validation

Staining and Scoring Protocol

- Automated Staining: Perform IHC using fully automated research stainer (Leica BOND RX) with specific primary antibodies according to manufacturing guidelines

- Controls: Include positive and negative controls in each run

- Digital Imaging: Scan all stained slides and matching H&E sections with Vectra Polaris scanner at 20× magnification

- Quantitative Analysis: Utilize QuPath (version 0.3.2) with positive cell detection algorithm for nuclear immunostains; set parameters to default for DAB chromogen with adjustments for cell size and optical density thresholds calibrated on control slides