Gene Function Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern gene function analysis, bridging fundamental concepts with cutting-edge methodologies.

Gene Function Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern gene function analysis, bridging fundamental concepts with cutting-edge methodologies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of functional genomics, details high-throughput experimental and computational techniques, addresses common challenges in data interpretation and optimization, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing knowledge across these four core intents, this guide serves as an essential resource for advancing therapeutic discovery and translating genomic data into clinical insights.

Understanding the Blueprint: Core Concepts and Definitions in Gene Function

Gene function is a multidimensional concept in modern molecular biology, encompassing both specific biochemical activities and broader roles in biological processes. A significant conceptual void exists between the molecular description of a gene's function—such as "DNA-binding transcription activator"—and its physiological role in an organism, described in terms like "meristem identity gene" [1]. This dualism underscores a critical challenge: while a gene's function can be described through its molecular interactions, a complete understanding requires integrating this knowledge into the complex network of biological systems where genes and their products operate [1]. Defining gene function by a single symbol or a macroscopic phenotype carries the misleading implication that a gene has one exclusive function, which is highly improbable for genes in complex multicellular organisms where functional pleiotropy is the norm [1].

Foundational Concepts and Classical Approaches

The Classical Genetic Approach: From Phenotype to Genotype

The classical approach to defining gene function begins with the identification of mutant organisms exhibiting interesting or unusual morphological or behavioral characteristics—fruit flies with white eyes or curly wings, for example [2]. Researchers work backward from the phenotype (the observable appearance or behavior of the individual) to determine the genotype (the specific form of the gene responsible for that characteristic) [2]. This methodology relies on the fundamental principle that mutations disrupting cellular processes provide critical insights into gene function, as the absence or alteration of a gene's product reveals its normal biological role through the resulting physiological defects [2].

Before gene cloning technology emerged, most genes were identified precisely through the processes disrupted when mutated [2]. This approach is most efficiently executed in organisms with rapid reproduction cycles and genetic tractability, including bacteria, yeasts, nematode worms, and fruit flies [2]. While spontaneous mutants occasionally appear in large populations, the isolation process is dramatically enhanced using mutagens—agents that damage DNA to generate large mutant collections for systematic screening [2].

Genetic Screens and Complementation Analysis

Genetic screens represent a systematic methodology for examining thousands of mutagenized individuals to identify specific phenotypic alterations of interest [2]. Screen complexity ranges from simple phenotypes (like metabolic deficiencies preventing growth without specific amino acids) to sophisticated behavioral assays (such as visual processing defects in zebrafish detected through abnormal swimming patterns) [2].

For essential genes whose complete loss is lethal, researchers employ temperature-sensitive mutants [2]. These mutants produce proteins that function normally at a permissive temperature but become inactivated by slight temperature increases or decreases, allowing experimental control over gene function [2]. Such approaches have successfully identified proteins crucial for DNA replication, cell cycle regulation, and protein secretion [2].

When multiple mutations share the same phenotype, complementation testing determines whether they affect the same or different genes [2]. In this assay, two homozygous recessive mutants are mated; if their offspring display the mutant phenotype, the mutations reside in the same gene, while complementation (normal phenotype) indicates mutations in different genes [2]. This methodology has revealed, for instance, that 5 genes are required for yeast galactose digestion, 20 genes for E. coli flagellum assembly, and hundreds for nematode development from a fertilized egg [2].

Table 1: Classical Genetic Approaches for Defining Gene Function

| Approach | Methodology | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Random Mutagenesis | Treatment with chemical mutagens or radiation to induce DNA damage and create mutant libraries | Genome-wide mutant generation in model organisms (bacteria, yeast, flies, worms) |

| Insertional Mutagenesis | Random insertion of known DNA sequences (transposable elements, retroviruses) to disrupt genes | Drosophila P element mutagenesis; zebrafish and mouse mutagenesis using retroviruses |

| Genetic Screens | Systematic examination of thousands of mutants for specific phenotypic defects | Identification of genes involved in metabolism, visual processing, cell division, embryonic development |

| Temperature-Sensitive Mutants | Point mutations creating heat-labile proteins that function at permissive but not restrictive temperatures | Study of essential genes required for fundamental processes (DNA replication, cell cycle control) |

| Complementation Testing | Crossing homozygous recessive mutants to determine if mutations are in the same or different genes | Genetic pathway analysis; determining the number of genes involved in specific biological processes |

Modern Methodologies and Technological Innovations

Reverse Genetics and Targeted Gene Manipulation

Unlike classical forward genetics that begins with a phenotype, reverse genetics starts with a known gene or DNA sequence and works to determine its function through targeted manipulation [2]. This paradigm shift became possible with gene cloning technology and has been revolutionized by precise genome editing tools [1].

Key reverse genetics approaches include:

- Gene overexpression: Cloning cDNA into expression vectors to induce gain-of-function phenotypes [1]

- Gene suppression: Using RNA interference (shRNA) to inhibit gene expression through the miRNA pathway [1]

- Programmable genome editing: Utilizing ZFNs, TALENs, or CRISPR-Cas9 to generate targeted knock-out cells or organisms [1]

- Site-directed mutagenesis: Introducing specific mutations to study structure-function relationships [1]

These technologies enable the production of transgenic animal models of human diseases for therapeutic target identification and drug screening [1].

Multi-Omics Integration and Single-Cell Analysis

While genomics provides DNA sequence information, comprehensive functional understanding requires multi-omics approaches that integrate multiple biological data layers [3]:

- Transcriptomics: RNA expression levels

- Proteomics: Protein abundance and interactions

- Metabolomics: Metabolic pathways and compounds

- Epigenomics: DNA methylation and other epigenetic modifications

This integrative methodology provides systems-level views of biological processes, linking genetic information to molecular function and phenotypic outcomes in areas including cancer research, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders [3].

Single-cell genomics reveals cellular heterogeneity within tissues, while spatial transcriptomics maps gene expression within tissue architecture [3]. These technologies enable breakthrough applications in cancer research (identifying resistant subclones), developmental biology (tracking cell differentiation), and neurological disease (mapping gene expression in affected brain regions) [3].

Semantic Design with Genomic Language Models

A cutting-edge innovation in functional genomics is semantic design using genomic language models like Evo, which learns from prokaryotic genomic sequences to perform function-guided design [4]. This approach leverages the distributional hypothesis of gene function—"you shall know a gene by the company it keeps"—where functionally related genes often cluster together in operons [4].

The Evo model enables in-context genomic design through a genomic "autocomplete" function, where DNA prompts encoding genomic context guide generation of novel sequences enriched for related functions [4]. Experimental validation demonstrates that Evo can generate functional toxin-antitoxin systems and anti-CRISPR proteins, including de novo genes with no significant sequence similarity to natural proteins [4]. This semantic design approach facilitates exploration of new functional sequence space beyond natural evolutionary constraints.

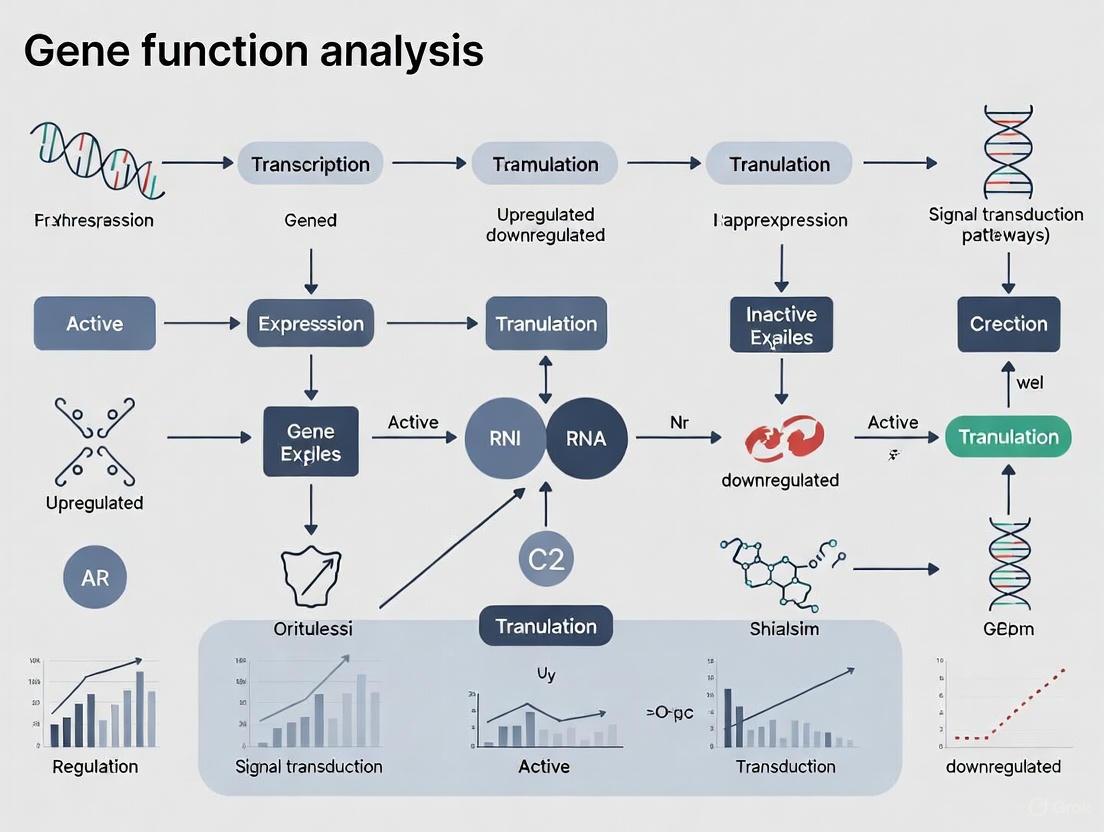

Diagram 1: Integrated Approaches for Defining Gene Function. This workflow illustrates the evolution from classical to modern methodologies for gene function analysis and their corresponding biological insights.

Perturb-Multimodal: Integrated Imaging and Sequencing

A recently developed method called Perturb-Multimodal (Perturb-Multi) simultaneously measures how genetic perturbations affect both gene expression and cell structure in intact tissue [5]. This innovative approach tests hundreds of different genetic modifications within a single mouse liver while capturing multiple data types from the same cells, eliminating inter-individual variability [5].

The power of this integrated methodology was demonstrated through discoveries in liver biology, including:

- Fat accumulation mechanisms: Four different genes caused similar fat droplet accumulation but operated through three distinct molecular pathways

- Liver cell zonation: Newly identified regulators included extracellular matrix modification genes, revealing unexpected flexibility in liver cell identity

- Stress responses: Integrated data provided unprecedented resolution of cellular stress pathways

Perturb-Multi overcomes previous limitations where measuring single data types captured only partial biological stories, analogous to understanding a movie with only visuals or sound [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Methodologies for Gene Function Determination

| Methodology | Throughput | Resolution | Key Functional Insights | Experimental Success Rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Mutagenesis & Screening | Moderate (hundreds of mutants) | Organismal/ Cellular | Identification of genes essential for specific processes | High for obvious phenotypes; lower for subtle defects |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing | High (thousands of guides) | Gene-level | Direct causal relationships between genes and functions | Variable (depends on efficiency of editing and screening) |

| Semantic Design (Evo Model) | Very High (millions of prompts) | Nucleotide-level | Generation of novel functional sequences beyond natural variation | Robust activity demonstrated for anti-CRISPRs and toxin-antitoxin systems [4] |

| Perturb-Multimodal | High (hundreds of genes per experiment) | Single-cell/ Subcellular | Integrated view of genetic effects on expression and morphology | High precision from same-animal experimental design [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Genetic Screen Implementation Protocol

A comprehensive genetic screen involves four critical phases [2]:

- Mutant generation: Treat organisms with chemical mutagens (EMS, ENU) or radiation, or utilize insertional mutagens (transposable P elements in Drosophila, retroviruses in zebrafish)

- Population establishment: Cross mutagenized individuals to establish stable mutant lines

- Phenotypic screening: Systematically examine progeny for defects in processes of interest using standardized assays

- Genetic analysis: Map mutation locations through complementation testing and linkage analysis

For temperature-sensitive mutants, a critical additional step involves replica plating at permissive versus restrictive temperatures to identify conditional lethals [2].

Perturb-Multimodal Experimental Workflow

The Perturb-Multi protocol integrates these key steps [5]:

- Vector design: Clone hundreds of sgRNAs targeting genes of interest into lentiviral vectors with unique barcodes

- In vivo delivery: Transduce hepatocytes in mouse liver using mosaic analysis to ensure single perturbations per cell

- Multimodal fixation: Perfusion-fix tissue under physiological conditions to preserve both RNA and protein integrity

- Spatial transcriptomics: Perform multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH) on tissue sections

- Immunofluorescence imaging: Stain for key proteins and cellular structures

- Image registration and analysis: Align sequencing and imaging data using computational pipelines

- Data integration: Correlate genetic perturbations with transcriptional and morphological changes

Diagram 2: Perturb-Multimodal Experimental Workflow. This protocol enables simultaneous measurement of genetic perturbation effects on gene expression and cellular morphology in intact tissue.

Semantic Design Protocol for De Novo Genes

The semantic design approach using the Evo genomic language model follows this methodology [4]:

- Prompt curation: Select genomic contexts encoding known functional elements (toxins, antitoxins, anti-CRISPRs)

- Contextual generation: Sample novel sequences from Evo using curated prompts to leverage genomic "guilt by association"

- In silico filtering: Apply computational filters for protein structure prediction, complex formation, and sequence novelty

- Synthetic construction: Manufacture top candidate sequences using DNA synthesis

- Functional validation: Test generated sequences in appropriate biological assays (growth inhibition for toxins, phage resistance for anti-CRISPRs)

- Iterative refinement: Use functional sequences as new prompts for further generation cycles

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Function Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis Tools | Induction of genetic variations for forward genetics | Chemical mutagens (EMS, ENU); Transposable elements (Drosophila P elements); Retroviral vectors (zebrafish) |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted gene disruption, editing, and regulation | Cas9 nucleases (wild-type, nickase, dead); sgRNA libraries; Base editors; Prime editors |

| Genomic Language Models | AI-guided design of novel functional sequences | Evo model (trained on prokaryotic genomes); Prompt engineering for semantic design [4] |

| Multimodal Fixation Reagents | Simultaneous preservation of RNA, protein, and tissue architecture | Specialized perfusion fixatives maintaining both transcriptomic and epitope integrity [5] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Reagents | Gene expression profiling with tissue context preservation | MERFISH probes; Barcoded oligo arrays; In situ sequencing chemistry |

| Multiplexed Imaging Antibodies | High-parameter protein detection in tissue sections | Conjugated antibodies for cyclic immunofluorescence; Validated for fixed tissue imaging [5] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | Resolution of cellular heterogeneity in gene function | 10X Genomics; Drop-seq; Nanostring DSP; Mission Bio Tapestri |

Defining gene function requires synthesizing knowledge across multiple biological scales—from molecular interactions to organismal phenotypes. No single methodology provides a complete picture; rather, integration of classical genetics, modern genomics, multi-omics technologies, and emerging artificial intelligence approaches offers the most powerful strategy for functional annotation [3] [2] [4]. The future of gene function analysis lies in developing increasingly sophisticated methods for multimodal data integration from intact biological systems, enabling researchers to build predictive "virtual cell" models that can accelerate both fundamental discovery and therapeutic development [5]. As these technologies mature, they will continue to bridge the conceptual void between molecular activity and biological role, ultimately providing a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of gene function in health and disease.

Functional genomics represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biological research, moving beyond static genome sequencing to dynamically understand how genes and networks function and interact. This field leverages high-throughput technologies to annotate genomic elements with biological function, translating sequence information into actionable insights for disease mechanisms, drug development, and bioengineering. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of core functional genomics methodologies, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks that enable genome-wide investigation of gene function. We detail cutting-edge techniques including single-cell multi-omics, CRISPR-based perturbation screening, and integrative data analysis, providing researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for systematic functional annotation of genomes.

The completion of the Human Genome Project marked a transition from sequencing to functional annotation, establishing functional genomics as a discipline focused on understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying gene expression, regulation, and cellular phenotypes [6]. Where traditional genetics often studied genes in isolation, functional genomics employs genome-wide approaches to systematically characterize gene function, regulatory networks, and their integrated activities across biological systems.

This paradigm leverages massively parallel sequencing technologies and high-throughput experimental methods to generate quantitative data about diverse molecular phenotypes, from chromatin accessibility and transcriptional outputs to protein-DNA interactions and epigenetic modifications [6]. The core objective remains the comprehensive functional annotation of genomic elements—both coding and non-coding—and understanding how their interactions translate genomic information into biological traits.

Core Methodologies in Functional Genomics

Genomic and Epigenomic Profiling

Functional genomics employs diverse sequencing-based assays to map functional elements and their regulatory landscape across the genome. These protocols generate epigenomic profiles that segment the genome into functionally distinct regions based on combinatorial chromatin patterns [6].

Table 1: Core Genomic and Epigenomic Assays

| Method | Molecular Target | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq [6] | Accessible chromatin | Mapping open chromatin regions, nucleosome positioning | Cell number critical: too few causes over-digestion, too many causes insufficient fragmentation |

| ChIP-seq [6] | Protein-DNA interactions | Transcription factor binding, histone modifications | Antibody quality paramount; improvements allow fewer cells and greater resolution |

| Bisulfite Sequencing [6] | DNA methylation | Single-nucleotide resolution methylation mapping | Potential false positives from unconverted cytosines; Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing distinguishes 5mC/5hmC |

| Hi-C & ChIA-PET [6] | 3D genome architecture | Topologically associating domains, chromatin looping | Combines proximity ligation with crosslinking; identifies enhancer-promoter interactions |

Transcriptomic Approaches

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) forms the backbone of transcriptome analysis, but specialized methods target specific RNA fractions and properties [6]. Cap analysis gene expression (CAGE) sequences 5' transcript ends to pinpoint transcription start sites and promoter regions using random primers that capture both poly(A)+ and poly(A)− transcripts [6]. Ribosome profiling identifies mRNAs undergoing translation, while CLIP-seq variants map RNA-protein interactions [6]. Short non-coding RNA profiling requires specific adapter ligation strategies, with polyadenylation approaches sacrificing precise 3' end identification [6].

Multi-Omics Integration at Single-Cell Resolution

Single-cell multi-omics technologies represent a transformative advancement, enabling simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers in individual cells. The recently developed single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) simultaneously profiles up to 480 genomic DNA loci and genes in thousands of single cells, enabling accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated gene expression changes [7]. This method combines in situ reverse transcription of fixed cells with multiplexed PCR in droplets, allowing confident linkage of precise genotypes to gene expression in their endogenous context [7]. SDR-seq addresses critical limitations of previous technologies that suffered from sparse data with high allelic dropout rates (>96%), making zygosity determination impossible at single-cell resolution [7].

SDR-seq Workflow: Simultaneous single-cell DNA and RNA profiling

High-Throughput Functional Perturbation Screening

CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics

CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized functional genomics by enabling highly multiplexed perturbation experiments where thousands of genetic manipulations occur in parallel within a cell population [6]. Unlike earlier technologies (zinc finger nucleases, TALENs) that required extensive protein engineering, CRISPR/Cas9 uses easily programmable guide RNAs to target specific genomic sites, enabling unprecedented scalability [6].

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) utilizes catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) to bind DNA without cleavage, blocking transcriptional machinery when targeted to promoter regions [6]. Efficiency improvements come from fusing repressor domains like KRAB to dCas9 to induce repressive histone modifications [6]. Similarly, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems fuse transactivating domains to dCas9 to enhance gene expression. For non-coding RNAs where single cuts may be insufficient, dual-CRISPR systems using paired guide RNAs can create complete gene deletions through dual double-strand breaks followed by non-homologous end-joining repair [6].

Experimental Design for Synergy Analysis

Advanced experimental designs enable resolution of synergistic effects between genetic variants or environmental factors. This requires combinatorial perturbation studies followed by RNA sequencing and specialized analytical frameworks [8]. The methodology specifically queries interactions between two or more perturbagens, resolving non-additive (synergistic) interactions that may underlie complex genetic disorders [8]. Careful experimental design is essential, including appropriate sample sizes, proper controls, and statistical power considerations for detecting interaction effects.

Table 2: CRISPR-Based Perturbation Systems

| System | Cas9 Variant | Key Components | Primary Applications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout [6] | Wild-type Cas9 | Single guide RNA | Protein-coding gene disruption | Indels via NHEJ, gene disruption |

| Dual CRISPR Deletion [6] | Wild-type Cas9 | Paired guide RNAs | lncRNA and regulatory element deletion | Complete locus excision |

| CRISPRi [6] | dCas9 | dCas9-KRAB fusion | Gene repression | Transcriptional knockdown |

| CRISPRa [6] | dCas9 | dCas9-activator fusion | Gene activation | Transcriptional enhancement |

| Base/Prime Editing [3] | Modified Cas9 | Cas9-reverse transcriptase fusions | Precise nucleotide changes | Single-base substitutions |

Data Analysis and Visualization Frameworks

Bioinformatics Considerations for Genomics Studies

Robust bioinformatics pipelines are essential for reliable functional genomics analysis. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and other omics approaches require special attention to multiple testing corrections due to millions of simultaneous statistical tests [9]. The standard significance threshold of P < 5 × 10⁻⁸ accounts for linkage disequilibrium between SNPs, representing approximately one million independent tests across the genome [9]. False discovery rate approaches provide less conservative alternatives to Bonferroni correction, balancing false positives and false negatives [9].

Critical study design elements include:

- Sample size justification for adequate statistical power

- Precise phenotype definition to reduce heterogeneity

- Population stratification control using principal components or genetic relationship matrices

- Batch effect accounting for technical variability

- Replication in independent cohorts or functional validation [9]

Proper model selection is paramount—linear regression for quantitative traits, logistic regression for dichotomous traits, and multivariate methods for complex traits [9]. Covariates like sex, age, and medications must be appropriately incorporated either as model covariates or through stratification.

Genomic Data Visualization

Effective visualization transforms complex genomic data into interpretable information. Different layouts serve distinct purposes: Circos plots arrange chromosomes circularly with tracks showing quantitative data and inner arcs depicting relationships like translocations, ideal for whole-genome comparisons [10]. Hilbert curves use space-filling layouts to preserve genomic sequence while integrating multiple datasets in compact 2D visualizations [10].

For transcriptomic data, volcano plots display significance versus magnitude of change, while heatmaps depict expression patterns across genes and samples [10]. Advanced network visualizations like hive plots provide linear layouts that reveal patterns in complex regulatory networks, overcoming "hairball" limitations of traditional force-directed layouts [10]. Color selection must ensure accessibility through color-blind-friendly palettes and sufficient contrast ratios following WCAG guidelines [10].

Functional Genomics Analysis Pipeline: From raw data to biological insight

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components [6] | Guide RNA libraries, Cas9 variants, dCas9-effector fusions | Targeted gene perturbation at scale | gRNA design critical for specificity; delivery methods vary (lentiviral, AAV, electroporation) |

| Antibodies for Epigenomics [6] | Histone modification-specific antibodies, transcription factor antibodies | Chromatin immunoprecipitation, protein localization | Antibody validation essential; cross-reactivity concerns require careful controls |

| Fixed Cell Preparations [7] | Paraformaldehyde, glyoxal | Cell preservation for in situ assays | Glyoxal improves RNA sensitivity vs PFA; crosslinking affects nucleic acid recovery |

| Barcoding Beads & Primers [7] | Cell hashing beads, sample barcodes, UMI primers | Single-cell multiplexing, sample pooling | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) correct for PCR amplification bias |

| Library Preparation Kits | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, RNA-seq kits | NGS library construction from limited input | Tagmentation-based approaches reduce hands-on time; input requirements vary |

| Single-Cell Partitioning [7] | Droplet-based systems, plate-based platforms | Single-cell resolution analysis | Partitioning efficiency impacts doublet rates; cell viability critical |

Future Directions and Applications

Functional genomics continues evolving through technological convergence. Artificial intelligence and machine learning now enable variant calling with superior accuracy (e.g., DeepVariant), disease risk prediction through polygenic scoring, and drug target identification [3]. Multi-omics integration combines genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to reveal comprehensive biological mechanisms, particularly valuable for complex diseases like cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [3].

Cloud computing platforms provide essential infrastructure for scalable genomic data analysis, offering computational resources that comply with regulatory standards like HIPAA and GDPR [3]. Emerging applications in personalized medicine leverage functional genomics for pharmacogenomics, targeted cancer therapies, and gene therapies using CRISPR-based approaches [3]. The expanding agrigenomics sector applies these tools to develop crops with improved yield, disease resistance, and environmental adaptability [3].

Current capabilities in functional genomics were highlighted in the DOE Joint Genome Institute's 2025 awards, including projects engineering drought-tolerant bioenergy crops through transcriptional network mapping, developing microbial systems for advanced biofuel production, and harnessing biomineralization processes for next-generation materials [11]. These applications demonstrate the translation of functional genomics principles into solutions addressing energy, environmental, and biomedical challenges.

The paradigm of functional genomics has fundamentally transformed our approach to investigating biological systems. By employing genome-wide, high-throughput methodologies, researchers can now systematically annotate gene function, decipher regulatory networks, and understand how genetic variation translates to phenotypic diversity. The integration of cutting-edge perturbation technologies like CRISPR with single-cell multi-omics and advanced computational analytics provides unprecedented resolution for studying gene function in health and disease. As these technologies continue evolving and converging with artificial intelligence, functional genomics will increasingly enable predictive biology and precision interventions across medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

In the field of genetics and molecular biology, determining the functional consequences of genetic sequence variants represents a major challenge for research and clinical diagnostics. Among the thousands of variants identified through next-generation sequencing, the largest category consists of variants of uncertain significance (VUS), which precludes molecular diagnosis, risk prediction, and targeted therapies [12]. Functional analysis of mutant phenotypes—the observable biochemical, cellular, or organismal characteristics resulting from genetic changes—provides the critical evidence needed to classify variants and understand their mechanistic roles in disease. This whitepaper examines the central role of mutant phenotypes in functional analysis, detailing key principles, quantitative methodologies, and advanced experimental frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals.

The fundamental premise is straightforward: introducing a specific genetic variant into an appropriate biological system and quantitatively measuring the resulting phenotypic changes can reveal the variant's pathogenicity, drug responsiveness, and underlying biological mechanism. Traditional approaches based on generating clonal cell lines are time-consuming and suffer from clonal variation artifacts [12]. Recent advances in CRISPR-based genome editing and sensitive quantification methods have enabled the development of powerful, quantitative assays that can determine variant effects on virtually any cell parameter in a controlled, efficient manner [12].

Key Principles of Functional Analysis via Mutant Phenotypes

The functional analysis of genetic variants through phenotypic screening rests on several foundational principles that ensure scientific rigor and biological relevance.

Table 1: Core Principles in Functional Analysis of Mutant Phenotypes

| Principle | Description | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Context | Analyzing variants in their proper genomic location preserves native regulatory elements and protein interactions. | CRISPR-mediated knock-in introduces variants at endogenous loci rather than using artificial overexpression systems [12]. |

| Controlled Comparison | Variant effects must be measured against an appropriate internal control to account for experimental variability. | Using a synonymous, neutral "WT prime" normalization mutation introduced alongside the variant of interest controls for editing efficiency and clonal variation [12]. |

| Quantitative Measurement | Phenotypic changes must be quantified with precision and accuracy to determine effect sizes. | Tracking absolute variant frequencies relative to control via next-generation sequencing provides quantitative, statistically robust data [12]. |

| Multiparametric Readouts | Comprehensive analysis requires assessing multiple phenotypic dimensions beyond simple proliferation. | Methodologies like CRISPR-Select enable tracking variant effects over TIME, across SPACE, and as a function of cell STATE [12]. |

| Biological Relevance | Experimental systems should reflect the physiological context in which the variant operates. | Using patient-relevant cell models (e.g., MCF10A breast epithelial cells) maintains pathophysiological relevance [12]. |

The Ameliorative and Deteriorating Effects of Modifier Mutations

Beyond simply establishing pathogenicity, functional analysis can reveal more complex genetic interactions. In the context of β-thalassemia, mutations in the transcription factor KLF1 can display either ameliorative or deteriorating effects on disease severity. Some KLF1 mutations cause haploinsufficiency linked to increased fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and hemoglobin A2 (HbA2) levels, which can reduce the severity of β-thalassemia [13]. However, functional studies have revealed that certain KLF1 mutations may instead have deteriorating effects by increasing KLF1 expression levels or enhancing its transcriptional activity [13]. This principle highlights that functional studies are essential to evaluate the net effect of mutations, particularly when multiple mutations co-exist and could differentially contribute to the overall disease phenotype [13].

Quantitative Methodologies for Phenotypic Assessment

CRISPR-Select: A Multiparametric Functional Variant Assay

The CRISPR-Select system represents a advanced methodological framework for functional variant analysis that accommodates diverse phenotypic readouts while controlling for key experimental confounders. This approach involves three specialized assays that track variant frequencies relative to an internal control mutation [12]:

- CRISPR-SelectTIME: Tracks variant frequencies as a function of time to determine effects on cell proliferation and survival

- CRISPR-SelectSPACE: Monitors variant frequencies across spatial dimensions to assay effects on cell migration or invasiveness

- CRISPR-SelectSTATE: Measures variant frequencies as a function of a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) marker to determine effects on any physiological/pathological state or biochemical process

The core CRISPR-Select cassette consists of: (1) a CRISPR-Cas9 reagent designed to elicit a DNA double-strand break near the genomic site to be mutated; (2) a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair template containing the variant of interest; and (3) a second ssODN repair template with a synonymous, internal normalization mutation (WT') otherwise identical to the first ssODN [12].

CRISPR-Select Experimental Framework

Validation of CRISPR-Select with Known Cancer Mutations

CRISPR-Select has been quantitatively validated using known driver mutations in relevant biological contexts. When tested in MCF10A immortalized human breast epithelial cells, the method successfully detected expected phenotypic effects [12]:

- PIK3CA-H1047R (gain-of-function): Showed ~13-fold enrichment under serum- and growth factor-depleted conditions

- PTEN-L182* (loss-of-function): Demonstrated accumulation consistent with known driver function

- BRCA2-T2722R (loss-of-function): Revealed ~5-fold loss of variant cells over time

Table 2: Quantitative Results from CRISPR-SelectTIME Validation Experiments

| Gene | Variant | Variant Type | Fold Change | Biological Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA | H1047R | Gain-of-function | ~13x Enrichment | Enhanced proliferation/survival under nutrient stress [12]. |

| PTEN | L182* | Loss-of-function | Accumulation | Driver function in tumor suppression loss [12]. |

| BRCA2 | T2722R | Loss-of-function | ~5x Loss | Defective DNA repair impairing cellular proliferation [12]. |

The quantitative power of CRISPR-Select stems from its ability to control for sufficient cell numbers, with experiments typically tracking the fate of approximately 1,300-1,600 variant or control cells from early time points, effectively diluting out potential confounding effects from clonal variation [12].

Quantitative PCR for Gene Expression Analysis in Functional Studies

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) serves as a cornerstone methodology for measuring gene expression changes resulting from genetic variants. Also known as real-time PCR, this technique enables accurate quantification of gene expression levels by monitoring PCR amplification as it occurs, providing quantitative data that is both sensitive and specific [14].

The reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) process involves several critical steps that must be rigorously controlled: (1) extraction of high-quality RNA; (2) reverse transcription to generate complementary DNA (cDNA); (3) amplification and detection of target sequences using fluorescent dyes or probes; and (4) normalization using appropriate reference genes [14] [15].

qPCR Gene Expression Analysis Workflow

A key advantage of qPCR is its focus on the exponential phase of PCR amplification, which provides the most precise and accurate data for quantitation. During this phase, the instrument calculates the threshold (fluorescence intensity above background) and CT (the PCR cycle at which the sample reaches the threshold) values used for absolute or relative quantitation [14].

For gene expression studies, the two-step RT-qPCR approach is commonly used because it offers flexibility in primer selection and the ability to store cDNA for multiple applications. This method uses reverse transcription primed with either oligo d(T)16 (which binds to the poly-A tail of mRNA) or random primers (which bind across the length of the RNA) [14].

Proper normalization is critical for reliable qPCR results. The use of unstable reference genes can lead to substantial differences in final results [15]. The comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method enables relative quantitation of gene expression, allowing researchers to quantify differences in expression levels of a specific target between different samples, expressed as fold-change or fold-difference [14].

Experimental Protocols

CRISPR-Select Protocol for Functional Variant Analysis

Principle: This protocol enables functional characterization of genetic variants by tracking their frequency relative to an internal control mutation over time, space, or cell state [12].

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., MCF10A for breast cancer studies)

- Synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) targeting genomic site of interest

- Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with variant and WT' sequences

- Lipofection or electroporation equipment

- Next-generation sequencing platform

- Optional: FACS sorter for CRISPR-SelectSTATE

Procedure:

Design CRISPR-Select Cassette:

- Design gRNA such that variant and WT' mutations are located in the seed region or PAM of the CRISPR-Cas9 binding site to minimize post-knock-in recutting.

- Design two ssODN repair templates: one containing the variant of interest and another with a synonymous, internal normalization mutation (WT') at the same or nearly the same position.

Delivery to Cells:

- Deliver the complete CRISPR-Select cassette (CRISPR-Cas9 reagent, gRNA, and both ssODNs) to the cell population using appropriate transfection method.

- For iCas9-MCF10A cells, pretreat with doxycycline to induce Cas9 expression before lipofection of synthetic gRNA and ssODNs.

Tracking Variant Frequencies:

- CRISPR-SelectTIME: Collect cell population aliquots at multiple time points (e.g., day 2, 4, 6, 8 post-editing).

- CRISPR-SelectSPACE: Assess variant distribution across spatial dimensions (e.g., transwell migration assays).

- CRISPR-SelectSTATE: Analyze variant frequency as a function of FACS markers for specific cell states.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA from cell aliquots.

- Perform genomic PCR amplification of target site using primers annealing outside regions covered by ssODNs.

- Sequence amplicons using NGS to determine types and frequencies of all editing outcomes.

- Calculate absolute numbers of knock-in alleles based on known genomic template amounts for PCR.

Data Interpretation:

- Calculate variant:WT' ratio for each experimental condition.

- For CRISPR-SelectTIME, plot ratio changes over time to determine effects on proliferation/survival.

- Ensure sufficient knock-in cell numbers (>1000 recommended) for statistical reliability.

Quantitative PCR Protocol for Gene Expression Analysis

Principle: This protocol enables precise quantification of gene expression changes resulting from genetic variants using reverse transcription quantitative PCR [14] [15].

Materials:

- High-quality RNA samples

- TRIzol or commercial RNA extraction kit

- UV/VIS spectrophotometer for RNA quantification

- Reverse transcription reagents

- qPCR instrument and reagents

- Target-specific primers or probes

Procedure:

RNA Extraction:

- Lyse cells or tissue in TRIzol reagent.

- Separate RNA using chloroform extraction.

- Precipitate RNA with 2-propanol (provides higher yield than ethanol).

- Wash RNA pellet with 75% ethanol and resuspend in RNase-free water.

RNA Quality Assessment:

- Measure RNA concentration using spectrophotometer (A260 of 1.0 = 40 μg/mL RNA).

- Assess purity: A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.1 indicates pure RNA.

- Check RNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer.

Reverse Transcription:

- Use 100 ng-1 μg total RNA per reaction.

- Perform reverse transcription using random hexamers or oligo-dT primers.

- Use consistent RNA input across all samples for comparable results.

qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Select detection chemistry: SYBR Green or TaqMan probes.

- Prepare reaction mix containing cDNA template, primers/probe, and master mix.

- Run reactions in triplicate for statistical reliability.

Data Analysis:

- Determine CT values for target and reference genes.

- Use comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method for relative quantification.

- Calculate fold-change in gene expression between experimental conditions.

Quality Control Considerations:

- Ensure PCR amplification efficiency between 90-110%.

- Include no-template controls to detect contamination.

- Validate reference gene stability across experimental conditions.

- Document all procedures following MIQE guidelines [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Analysis of Genetic Variants

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 reagents, synthetic gRNA, ssODN repair templates | Introduce specific variants into endogenous genomic locations in relevant cell models [12]. |

| Cell Models | MCF10A, organoids, nontransformed or cancer cell lines | Provide biologically relevant contexts for assessing variant effects in proper cellular environments [12]. |

| RNA Extraction Reagents | TRIzol, Tri-reagent, commercial extraction kits | Isolate high-quality RNA from biological samples while maintaining RNA integrity for downstream applications [15]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Random hexamers, oligo-dT primers, reverse transcriptase enzymes | Convert mRNA to stable cDNA for subsequent qPCR analysis of gene expression [14]. |

| qPCR Reagents | SYBR Green, TaqMan probes, primer sets, master mixes | Enable accurate quantification of gene expression levels through fluorescent detection of amplified DNA [14]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Amplicon sequencing kits, NGS platforms | Precisely quantify editing outcomes and variant frequencies in cell populations with high accuracy [12]. |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | Fluorescent antibodies, viability dyes, FACS buffers | Enable cell sorting and analysis based on specific markers for CRISPR-SelectSTATE applications [12]. |

Functional analysis through mutant phenotypes provides an essential framework for bridging the gap between genetic sequence variants and their biological consequences. The integration of advanced genome editing technologies with multiparametric phenotypic readouts enables comprehensive characterization of variant effects on proliferation, survival, migration, and diverse cellular states. Quantitative methodologies including CRISPR-Select and qPCR offer sensitive, reproducible approaches for determining variant pathogenicity, drug responsiveness, and mechanism of action. As functional assays continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly critical role in research, diagnostics, and drug development for genetic disorders, ultimately addressing the challenge of variants of uncertain significance and enabling precision medicine approaches.

Genome annotation is the foundational process of identifying and interpreting the functional elements within a genome, connecting genetic information to biological function, disease mechanisms, and evolutionary relationships [16]. This process is critical for making sense of the enormous volume of DNA sequence data generated from modern sequencing projects [17]. The exponential growth in available sequences presents a monumental challenge: with over 19 million protein sequences in UniProtKB databases, only 2.7% have been manually reviewed, and many of these are still defined as uncharacterized or of putative function [17]. This annotation deficit highlights the critical need for sophisticated computational approaches to guide experimental determination and annotate proteins of unknown function, forming an essential bridge between raw sequence data and biological understanding for researchers and drug development professionals.

The annotation challenge spans multiple dimensions, from nucleotide-level identification to biological system-level interpretation [16]. Genomic elements of interest include not only coding genes but also noncoding genes, regulatory elements, single nucleotide polymorphisms, and various noncoding regions [16]. While structural annotation provides initial clues by delineating physical regions of genomic elements, definitive functional understanding requires integrated analysis across multiple data types and biological contexts. This comprehensive guide examines the current state, challenges, and future directions in genomic annotation, providing researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical methodologies for advancing gene function analysis.

The Core Challenges in Modern Genome Annotation

Data Volume and Quality Concerns

The relentless pace of sequencing technology advancement has created a fundamental imbalance between data generation and annotation capabilities. Current automated methods face significant challenges in accurately predicting gene structures and functions due to the relative scarcity of reliable labeled data and the complexity of biological systems [16]. This problem is particularly acute for non-model organisms, where genes are often assigned functions based solely on homology or labeled with uninformative terms such as "hypothetical gene" or "expressed protein," providing little insight into their actual biological roles [16]. These inaccuracies propagate through downstream analyses, creating a feedback loop where low-quality annotations degrade the reliability of both current databases and future research dependent on them [16].

The limitations of computational tools often lead to erroneous annotations that impact drug discovery and basic research. Misannotation propagation represents a particularly serious concern, as these errors become amplified by machine learning or AI models trained on the flawed data [16]. For mammalian genomes, additional complications arise from gene expansion events during evolution, whose identification remains challenging due to potential errors in genome assembly and annotation [18]. These foundational issues underscore the importance of quality control throughout the annotation pipeline, especially for researchers investigating novel drug targets or therapeutic pathways.

Functional Annotation and nsSNP Interpretation

Accurately determining gene function represents perhaps the most significant challenge in genomic annotation. Current methods primarily rely on detecting similarities using homology between sequences and structures, but this approach struggles with predicting changes in function that are not immediately available through conservation analysis [17]. This limitation becomes particularly evident in the context of population genomic studies, where resolving the consequences of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) on protein structure and function presents substantial difficulties [17].

The annotation of nsSNPs requires specialized methodologies to classify them into functionally neutral variants versus those affecting protein structure or function. Amino acid substitution methods based on multiple sequence alignment conservation, structure-based methods analyzing the structural context of substitutions, and hybrid approaches combining both strategies have been developed to assess nsSNP impact [17]. These analyses must always consider the structural and functional constraints imposed by the protein, as mutations can affect catalytic activity, allosteric regulation, protein-protein interactions, or protein stability [17]. For drug development professionals, accurate nsSNP annotation is crucial for understanding genetic determinants of drug response and disease susceptibility.

Table 1: Methods for Assessing nsSNP Impact on Protein Function

| Method Category | Primary Basis | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Substitution | Multiple sequence alignment conservation | Classifying functionally neutral vs. deleterious variants | Limited structural context consideration |

| Structure-Based | Protein structural context | Analyzing substitutions in active sites or binding interfaces | Requires high-quality structural models |

| Hybrid Approaches | Combined sequence and structure analysis | Comprehensive functional impact assessment | Computational intensity and complexity |

Methodologies and Experimental Frameworks

Integrated Annotation Pipelines

Comprehensive genome annotation requires sophisticated computational pipelines that integrate multiple evidence types and prediction algorithms. For mammalian genomes, a typical workflow combines evidence-based and ab initio approaches, with pipelines like MAKER2 providing robust frameworks for annotation [18]. The process begins with repeat masking, a critical first step that identifies and masks repetitive elements to prevent non-specific gene hits during annotation [18]. This involves constructing species-specific repetitive elements using RepeatModeler and masking common repeat elements with RepeatMasker using RepBase repeat libraries alongside the newly identified species-specific repeats [18].

The next critical phase involves training gene prediction models using both evidence-based and ab initio approaches. The AUGUSTUS tool can be trained using BUSCO with the "--long" parameter to enable full optimization for self-training, significantly improving accuracy for non-model organisms [18]. Similarly, SNAP undergoes iterative training, typically through three rounds, where the trained parameter/HMM file from each round seeds subsequent training iterations [18]. The MAKER pipeline integrates these components, running on single processors or parallelized across multiple nodes depending on genome size and complexity, with execution times ranging from days to weeks for large mammalian genomes [18].

Validation and Quality Assessment

Rigorous validation is essential for producing high-quality genome annotations. BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) provides a crucial quality assessment by evaluating annotation completeness based on evolutionarily informed expectations of gene content [18]. This tool assesses whether a expected set of genes from a specific lineage is present in the annotation, offering a quantitative measure of completeness. For gene expansion analysis, CAFE5 enables computational validation by modeling gene family evolution across species [18].

Experimental validation typically involves transcriptome analysis using tools like Kallisto for RNA-seq quantification, providing experimental evidence for predicted gene models [18]. The integrative genome browser Apollo offers a platform for manual curation and validation, allowing researchers to visualize and edit gene models based on experimental evidence [18]. This manual curation capability is particularly valuable for resolving complex genomic regions and verifying gene boundaries through integration of multiple evidence types, including RNA-seq alignments and homologous protein matches.

Table 2: Key Tools for Genome Annotation and Validation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAKER2 | Genome annotation pipeline | Integrated annotation | Combines evidence and ab initio predictions |

| BUSCO | Quality assessment | Completeness evaluation | Measures against conserved ortholog sets |

| RepeatMasker | Repeat identification | Pre-processing | Masks repetitive elements |

| AUGUSTUS | Gene prediction | Structural annotation | Ab initio gene finding |

| Apollo | Manual curation | Validation and refinement | Web-based collaborative editing |

| CAFE5 | Gene family evolution | Evolutionary analysis | Models gene gain/loss across species |

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

Human-AI Collaborative Frameworks

The emerging field of human-AI collaboration represents a promising paradigm shift for addressing genome annotation challenges. The Human-AI Collaborative Genome Annotation (HAICoGA) framework proposes a synergistic partnership where humans and AI systems work interdependently over sustained periods [16]. In this model, AI systems generate annotation suggestions by leveraging automated tools and relevant resources, while human experts review and refine these suggestions to ensure biological context alignment [16]. This iterative collaboration enables continuous improvement, with humans and AI systems mutually informing each other to enhance both accuracy and usability.

Current AI systems in genome annotation primarily function as Level 0 AI models that humans use as automated tools [16]. The development of AI assistants (Level 1) that execute tasks specified by scientists and AI collaborators (Level 2) that work alongside researchers to refine hypotheses represents the next evolutionary step [16]. Large language models (LLMs) show particular promise for supporting specific annotation tasks through their ability to process biological literature and integrate disparate data sources [16]. This collaborative approach leverages the strengths of both human expertise and AI scalability, potentially accelerating annotation while maintaining biological accuracy.

Multi-Omics Integration and Advanced Technologies

The integration of multi-omics data represents a powerful approach for enhancing annotation accuracy and functional insights. While genomics provides the foundational DNA sequence information, transcriptomics (RNA expression), proteomics (protein abundance and interactions), metabolomics (metabolic pathways), and epigenomics (epigenetic modifications) provide complementary layers of biological information [3]. This integrative approach offers a comprehensive view of biological systems, linking genetic information with molecular function and phenotypic outcomes, which is particularly valuable for complex disease research and drug target identification [3].

Advanced sequencing and analysis technologies are further expanding annotation capabilities. Single-cell genomics reveals cellular heterogeneity within tissues, while spatial transcriptomics maps gene expression in the context of tissue structure [3]. For functional validation, CRISPR-based technologies enable precise gene editing and interrogation, with high-throughput CRISPR screens identifying critical genes for specific diseases [3]. Base editing and prime editing represent refined CRISPR tools that allow even more precise genetic modifications for functional studies [3]. These technologies provide unprecedented resolution for connecting genomic sequences to biological functions in relevant cellular contexts.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful genome annotation requires carefully selected research reagents and computational resources. The following toolkit represents essential components for comprehensive annotation projects, particularly for mammalian genomes where annotation complexity is substantial.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Annotation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Annotation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X, Oxford Nanopore | Generate raw genomic and transcriptomic data | Long-read vs. short-read tradeoffs |

| Annotation Pipelines | MAKER2, BRAKER2, Ensembl | Integrated structural and functional annotation | Customization for target organisms |

| Quality Assessment Tools | BUSCO, GeneValidator | Evaluate annotation completeness and accuracy | Lineage-specific benchmark sets |

| Repeat Identification | RepeatMasker, RepeatModeler | Identify and mask repetitive elements | Species-specific repeat libraries |

| Manual Curation Platforms | Apollo, IGV | Visualize and manually refine annotations | Collaborative features for team science |

| Functional Validation | Kallisto, STAR | Experimental validation of predictions | Integration with multi-omics data |

Genome annotation remains a dynamic and challenging field, balancing the exponential growth of sequence data with the persistent need for accurate functional interpretation. The core challenges of data volume, quality control, and functional prediction require integrated approaches that combine computational power with biological expertise. Emerging methodologies, particularly human-AI collaborative frameworks and multi-omics integration, offer promising paths toward more comprehensive and accurate annotations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding both the capabilities and limitations of current annotation approaches is essential for designing effective studies and interpreting results. As annotation technologies continue to evolve, the research community moves closer to the ultimate goal of complete functional characterization of genomic sequences—a achievement that would fundamentally advance our understanding of biology and disease mechanisms. The ongoing refinement of annotation methodologies will continue to serve as a critical foundation for biomedical discovery and therapeutic development in the coming decades.

Model Organisms as Windows into Human Gene Function

The functional characterization of the human genome represents one of the paramount challenges in modern biology and biomedical research. While the human genome contains approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes, direct experimental investigation of their functions faces significant practical and ethical limitations [19]. This whitepaper examines how model organisms serve as indispensable experimental systems for elucidating human gene function through comparative genomics, evolutionary modeling, and functional screening approaches. We detail how the integration of experimental data from evolutionarily related species enables the reconstruction of functional repertoires for human genes, with approximately 82% of human protein-coding genes now having functional annotations derived through these methods [20] [21]. The methodologies and insights presented herein provide a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in gene function analysis.

A comprehensive, computable representation of the functional repertoire of all macromolecules encoded within the human genome constitutes a foundational resource for biology and biomedical research [20]. Direct experimental determination of human gene function faces considerable constraints, including ethical limitations, technical challenges in manipulating human systems, and the vast scale of the genome itself. Model organisms—from bacteria and yeast to flies, worms, and mice—provide experimentally tractable systems for investigating gene functions that are evolutionarily conserved across species.

The Gene Ontology Consortium has worked toward this goal by generating a structured body of information about gene functions, which now includes experimental findings reported in more than 175,000 publications for human genes and genes in model organisms [20] [21]. This curated knowledge base enables the application of explicit evolutionary modeling approaches to infer human gene functions based on experimental evidence from related species.

Table: Quantitative Overview of Human Gene Function Annotation through Evolutionary Modeling

| Metric | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-coding genes with functional annotations | ~82% | Coverage of human protein-coding genes through integrated approaches [21] |

| Experimental publications in GO knowledgebase | >175,000 | Foundation of primary experimental evidence [20] |

| Integrated gene functions in PAN-GO resource | 68,667 | Synthesized functional characteristics [20] |

| Phylogenetic trees modeled | 6,333 | Evolutionary scope of inference framework [20] |

| Human genes in UAE family | 10 | Example of functional diversification within a gene family [20] |

Evolutionary Principles of Functional Conservation

The Evolutionary Modeling Framework

The phylogenetic annotation using Gene Ontology (PAN-GO) approach implements expert-curated, explicit evolutionary modeling to integrate available experimental information across families of related genes. This methodology reconstructs the gain and loss of functional characteristics over evolutionary time [20]. The system operates through three fundamental steps: (1) systematic review of all functional evidence in the GO knowledgebase for related genes within an evolutionary tree of a gene family; (2) selection of a maximally informative and independent set of functional characteristics; and (3) construction of an evolutionary model specifying how each functional characteristic evolved within the gene family [20].

This explicit evolutionary modeling represents a significant advance over previous homology-based methods. Earlier approaches that used protein families (e.g., Pfam, InterPro2GO) or subfamilies and orthologous groups (e.g., PANTHER, COGs) were limited to representing functional characteristics broadly conserved across entire families or subfamilies, often lacking coverage and precision [20]. Similarly, methods based on pairwise identification of homology or orthology treated each homologous gene pair and functional characteristic in isolation rather than integrating experimental information across multiple related genes [20].

Case Study: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (UAE) Family

The ubiquitin-activating enzyme (UAE) family illustrates the power and methodology of evolutionary modeling for functional inference. This family is found in all kingdoms of life and includes ten human genes. Family members activate various ubiquitin-like modifiers (UBLs)—small proteins that, once activated, attach to other proteins to mark them for regulation [20].

The modeling process considers both the gene tree (indicating the origin of the ATG7 clade before the last common ancestor of eukaryotes) and sparse experimental knowledge of gene functions within the tree. Through this approach, the most informative, non-overlapping set of functional characteristics (GO classes) are selected, and an evolutionary model is created that specifies the tree branch along which each characteristic arose [20]. For human ATG7, the model infers inheritance of the functional characteristics "Atg12 activating enzyme activity" and "Atg8 activating enzyme activity," with evidence derived from experiments in mouse and budding yeast [20].

Table: Functional Diversification in the UAE Gene Family

| Gene/Clade | Evolutionary Origin | Functional Characteristics | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial UAE ancestors | Early evolution | Sulfotransferase activity | Experimental annotations in bacterial genes [20] |

| ATG7 clade | Before LCA of eukaryotes | Atg12 and Atg8 activating enzyme activity | Mouse and yeast experiments [20] |

| Human ATG7 | Inherited from eukaryotic ancestor | Atg8/Atg12 activating enzyme activity | Inferred from evolutionary model [20] |

| Human MOCS3 | Related eukaryotic clade | Sulfotransferase activity | Retained ancestral function [20] |

Experimental Methodologies for Functional Annotation

CRISPR-Cas9 Functional Screening Platforms

CRISPR-Cas9 systems have emerged as preferred tools for genetic screens, demonstrating improved versatility, efficacy, and lower off-target effects compared to approaches such as RNA interference (RNAi) [19]. In a typical pooled CRISPR knockout (CRISPR-ko) screen, a library of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) is introduced into a cell population such that each cell receives only one sgRNA [19]. This approach enables systematic loss-of-function analysis of multiple candidate genes in a single experiment.

The core mechanism involves the bacterial Cas enzyme (usually Cas9) being guided to a genomic DNA target by an approximately 20-nucleotide sgRNA sequence. Once at the target, Cas9 catalyzes a double-strand DNA break, which cells repair primarily through error-prone nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). This repair process introduces small insertions or deletions (indels) that lead to frameshifts and/or premature stop codons, resulting in loss-of-function [19].

Advanced Genome Editing Techniques

Beyond standard CRISPR knockout approaches, researchers have developed refined methods to address limitations of basic editing techniques. The SUCCESS (Single-strand oligodeoxynucleotides, Universal Cassette, and CRISPR/Cas9 produce Easy Simple knock-out System) method enables complete deletion of target genomic regions without constructing traditional targeting vectors [22].

This system utilizes two pX330 plasmids encoding Cas9 and gRNA, two 80mer single-strand oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), and a blunt-ended universal selection marker sequence to delete large genomic regions in cancerous cell lines [22]. The methodology addresses the limitation of standard INDEL approaches, where some cells continue to express the target gene through exon skipping or alternative splicing variants. Technical optimization revealed that blunt ends of the DNA cassette and ssODNs were crucial for increasing knock-in efficiency, while homologous arms significantly enhanced the efficiency of inserting the selection marker into the target genomic region [22].

Table: CRISPR Screening Platforms and Applications

| Component | Options | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide (GeCKO, Brunello) vs. targeted | Genome-scale comprehensive but resource-intensive; targeted focuses on specific gene classes [19] |

| Delivery Method | Lentiviral, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation | Lentiviral enables stable integration; cytotoxicity varies by method [19] |

| Cell Models | Primary cells vs. immortalized cell lines | Primary cells biologically relevant but technically challenging; cell lines more tractable [19] |

| Cas9 Expression | Stable expression vs. concurrent delivery | Stable lines provide uniform expression; concurrent delivery simpler [19] |

| Phenotypic Assay | Positive/negative selection, reporter systems | Must align with biological question; reporter systems enable complex phenotyping [19] |

Quantitative Framework for Annotation Quality Assessment

Metrics for Annotation Management

The management and comparison of annotated genomes requires specialized quantitative measures beyond simple gene and transcript counts [23]. Annotation Edit Distance (AED) provides a valuable metric for quantifying changes to individual annotations between genome releases. AED measures structural changes to annotations, complementing traditional metrics like gene and transcript numbers [23].

Application of AED to multiple eukaryotic genomes reveals substantial variation in annotation stability across species. Analysis shows that 94% of D. melanogaster genes have remained unaltered at the transcript coordinate level since 2004, with only 0.3% altered more than once. In contrast, 58% of C. elegans annotations in the current release have been modified since 2003, with 32% modified more than once [23]. These findings demonstrate how AED naturally supplements basic gene counts, revealing annotation dynamics that would otherwise remain hidden.

Comparative Analysis of Biological Features

The Yeast Quantitative Features Comparator (YQFC) addresses the challenge of directly comparing quantitative biological features between two gene lists [24]. This tool comprehensively collects and processes 85 quantitative features from yeast literature and databases, classified into four categories: gene features, mRNA features, protein features, and network features [24].

For each quantitative feature, YQFC provides three statistical tests (t-test, U test, and KS test) to determine whether the feature differs significantly between two input yeast gene lists [24]. This approach enables researchers to identify distinctive quantitative characteristics—such as mRNA half-life, protein abundance, or network connectivity—that differentiate gene sets identified through omics studies.

Table: Quantitative Measures for Genome Annotation Management

| Metric | Application | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation Edit Distance (AED) | Quantifies structural changes to annotations between releases | Values range 0-1; lower values indicate less change [23] |

| Annotation Turnover | Tracks addition/deletion of annotations across releases | Identifies "resurrection events"—deleted and recreated annotations [23] |

| Splice Complexity | Quantifies alternative splicing patterns | Enables cross-genome comparison of transcriptional complexity [23] |

| Quantitative Feature Comparison | Statistical testing of differences between gene lists | Identifies distinctive molecular characteristics [24] |

Integration of Multi-Species Data for Functional Prediction

The integration of experimental data across model organisms requires sophisticated computational frameworks that account for evolutionary relationships. The PAN-GO system models functional evolution across 6,333 phylogenetic trees in the PANTHER database, integrating all available experimental information from the GO knowledgebase [20]. This approach enables the reconstruction of functional characteristics based on their evolutionary history rather than simple sequence similarity.

The resulting resource provides a comprehensive view of human gene functions, with traceable evidence links that enable scientific community review and continuous improvement. The explicit evolutionary modeling captures functional changes that occur through gene duplication and specialization, representing a significant advance over methods that assume functional conservation across entire gene families [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Gene Function Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PAN-GO Evolutionary Models | Provides inferred human gene functions | Covers ~82% of human protein-coding genes; based on explicit evolutionary modeling [20] |

| GeCKO/Brunello Libraries | Genome-wide sgRNA collections | Enable comprehensive knockout screens; include negative controls and essential gene positive controls [19] |

| pX330 Plasmid System | CRISPR/Cas9 delivery vector | Enables precise genome editing; compatible with various sgRNA designs [22] |

| ssODNs (80mer) | Facilitate precise genomic integration | Critical for SUCCESS method; improve knock-in efficiency [22] |

| YQFC Tool | Quantitative feature comparison | Statistical analysis of 85 molecular features between gene lists [24] |

| Lentiviral Delivery Systems | Efficient gene transfer | Enable stable integration in difficult-to-transfect cells; require biosafety precautions [19] |

| AED Calculation Tools | Annotation quality assessment | Quantify changes between genome releases; identify problematic annotations [23] |

Model organisms provide indispensable experimental systems for elucidating human gene function through evolutionary principles and comparative genomics. The integration of data from diverse species through explicit evolutionary modeling enables the reconstruction of functional repertoires for human genes, with current resources covering approximately 82% of protein-coding genes [20] [21]. CRISPR-based screening platforms in model organisms offer powerful tools for systematic functional annotation, while quantitative metrics like Annotation Edit Distance enable robust management and comparison of genome annotations across releases [19] [23].

These approaches collectively address the fundamental challenge of human gene function annotation by leveraging evolutionary relationships and experimental tractability of model systems. The continued refinement of these methodologies—incorporating increasingly sophisticated evolutionary models, genome editing tools, and quantitative assessment frameworks—will further enhance our understanding of the functional repertoire encoded in the human genome, with significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Methodological Toolkit: From Classical Genetics to High-Throughput Omics

Classical forward genetics is a fundamental molecular genetics approach for determining the genetic basis responsible for a phenotype without prior knowledge of the underlying genes or molecular mechanisms [25]. This methodology provides an unbiased investigation because it relies entirely on identifying genes or genetic factors through the observation of mutant phenotypes, moving from phenotype to genotype in contrast to reverse genetics which proceeds from genotype to phenotype [25]. The core principle involves inducing random mutations throughout the genome, screening for individuals displaying phenotypes of interest, and subsequently identifying the causal genetic mutations through mapping and molecular analysis. This approach has been instrumental in elucidating gene function across model organisms and continues to provide valuable insights into biological processes, disease mechanisms, and potential therapeutic targets.

The power of forward genetics lies in its lack of presuppositions about which genes might be involved in a biological process. Researchers can discover novel, previously uncharacterized genes that participate in specific pathways or contribute to particular traits. This unbiased nature makes forward genetics particularly valuable for investigating complex biological phenomena where the genetic players may not be obvious from existing knowledge. Furthermore, the random nature of mutagenesis means that any gene in the genome can potentially be mutated and associated with a phenotype, providing comprehensive coverage of genetic contributions to traits.

Key Methodologies and Mutagenesis Techniques

Mutagenesis Methods

Forward genetics employs several well-established mutagenesis techniques to introduce random DNA mutations, each with distinct molecular outcomes and applications. The choice of mutagenesis method depends on the organism, the desired mutation density, and the available resources for subsequent mutation identification. The three primary categories of mutagens used in forward genetics are chemical mutagens, radiation, and insertional elements, each creating characteristic types of genetic alterations that can be leveraged for gene discovery.

Table 1: Mutagenesis Methods in Forward Genetics

| Method | Mutagen | Mutation Type | Key Features | Organism Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Mutagenesis | Ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) | Point mutations (G/C to A/T transitions) | Creates dense mutation spectra; often generates loss-of-function alleles [25] | Plants, C. elegans, Drosophila |

| N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) | Random point mutations | Induces gain or loss-of-function mutations; effective in vertebrates [25] | Mice, zebrafish | |

| Radiation Mutagenesis | X-rays, gamma rays | Large deletions, chromosomal rearrangements | Causes significant structural alterations; useful for generating null alleles [26] [25] | Plants, Drosophila |