Model Organisms in Functional Genomics: From Gene Function to Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how model organisms are revolutionizing functional genomics to bridge the gap between genetic information and biological function.

Model Organisms in Functional Genomics: From Gene Function to Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how model organisms are revolutionizing functional genomics to bridge the gap between genetic information and biological function. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of using non-mammalian models like zebrafish, Drosophila, and C. elegans in high-throughput studies. The scope spans from core concepts and cutting-edge CRISPR-based methodologies to practical troubleshooting and the critical validation of gene-disease associations. By synthesizing insights from recent protocols, industry applications, and initiatives like the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to accelerate gene discovery, deconvolute disease mechanisms, and identify novel therapeutic targets.

The Essential Role of Model Organisms in Decoding Gene Function

Defining Functional Genomics and Its Goals in Model Systems

Functional genomics is the field of research that bridges the gap between an organism's genetic code (genotype) and its observable traits and health outcomes (phenotype) [1]. While sequencing technologies have enabled the massive generation of genomic data, the fundamental challenge of modern biology remains: to completely predict phenotype based on genotype [2]. Functional genomics addresses this challenge by leveraging data from multiple biological modalities—genome sequences, transcriptomes, epigenomes, proteomes, and metabolomes—to understand how genetic variation changes an organism at the level of protein functions, gene regulation, and complex genetic interactions [2].

The core goals of functional genomics in model systems include:

- Systematic perturbation of genes and/or regulatory regions to analyze ensuing phenotypic changes at scale

- Deciphering the operational instructions of the genome, particularly the vast non-coding regions

- Linking genetic variations to disease mechanisms and biological pathways

- Enabling predictive models of biological systems for both basic research and therapeutic development

The Functional Genomics Imperative: Beyond Sequencing

The Challenge of Genomic Interpretation

Despite advances in sequencing technology, significant interpretation challenges remain. The human genome contains approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes, with about 70% having some functional assignment through various methods [2]. This leaves approximately 6,000 genes completely uncharacterized [2]. Furthermore, clinical sequencing encounters variants of uncertain significance (VUS) at rates 2.5 times higher than interpretable variants, creating a critical bottleneck in medical genomics [2].

The non-coding genome presents an even greater challenge. While over 90% of genome-wide association study (GWAS) variants for common diseases reside in non-coding regions, their gene regulatory impacts remain difficult to assess [3]. This "dark genome"—comprising approximately 98% of our DNA—acts as a complex set of switches and dials that orchestrate how and when our 20,000-25,000 genes work together [1].

Table 1: Key Challenges in Functional Genomic Interpretation

| Challenge Area | Specific Problem | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Characterization | ~6,000 human genes completely uncharacterized | Limited understanding of basic biological functions |

| Variant Interpretation | Variants of uncertain significance (VUS) dominate clinical findings | Diagnostic bottlenecks in genetic medicine |

| Non-coding Genome | 90% of disease-associated variants in non-coding regions | Difficulty linking GWAS hits to mechanisms |

| Complex Disease | Multiple genetic variants influence chronic diseases | Challenging therapeutic target identification |

The Drug Development Imperative

Functional genomics has become particularly crucial for pharmaceutical development, where drugs based on genetic evidence are twice as likely to achieve market approval [1]. This represents a vital improvement in a sector where nearly 90% of drug candidates fail, with average development costs exceeding $1 billion and timelines spanning 10-15 years [1]. Major pharmaceutical companies, including Johnson & Johnson and GSK, have made significant investments in functional genomics initiatives, recognizing the critical role of genetics in driving drug discovery and development [1].

Model Systems in Functional Genomics

Vertebrate Models: Mice and Zebrafish

Vertebrate models, particularly mice and zebrafish, provide essential platforms for functional genomics research that cannot be addressed in cell culture alone. These organisms enable the study of development, physiology, and tissue homeostasis in complex biological contexts [2].

Zebrafish have emerged as a powerful model for high-throughput functional genomics. Research teams have successfully used CRISPR-based approaches to screen hundreds of genes simultaneously. Examples include:

- Screening 254 genes to identify those essential for hair cell and tissue regeneration [2]

- Investigating over 300 genes for their role in retinal regeneration or degeneration [2]

- Targeting zebrafish orthologs of 132 human schizophrenia-associated genes [2]

- Generating mutants for 40 genes associated with childhood epilepsies [2]

Mice continue to serve as fundamental mammalian models, with CRISPR-Cas9 enabling efficient gene disruptions with efficiencies of 14-20% in early demonstrations [2]. The scalability of CRISPR technology has revolutionized functional studies in both model systems, with the first large germline dataset in vertebrates targeting 162 loci across 83 zebrafish genes showing a 99% success rate for generating mutations [2].

Functional Genomics Workflow in Model Systems

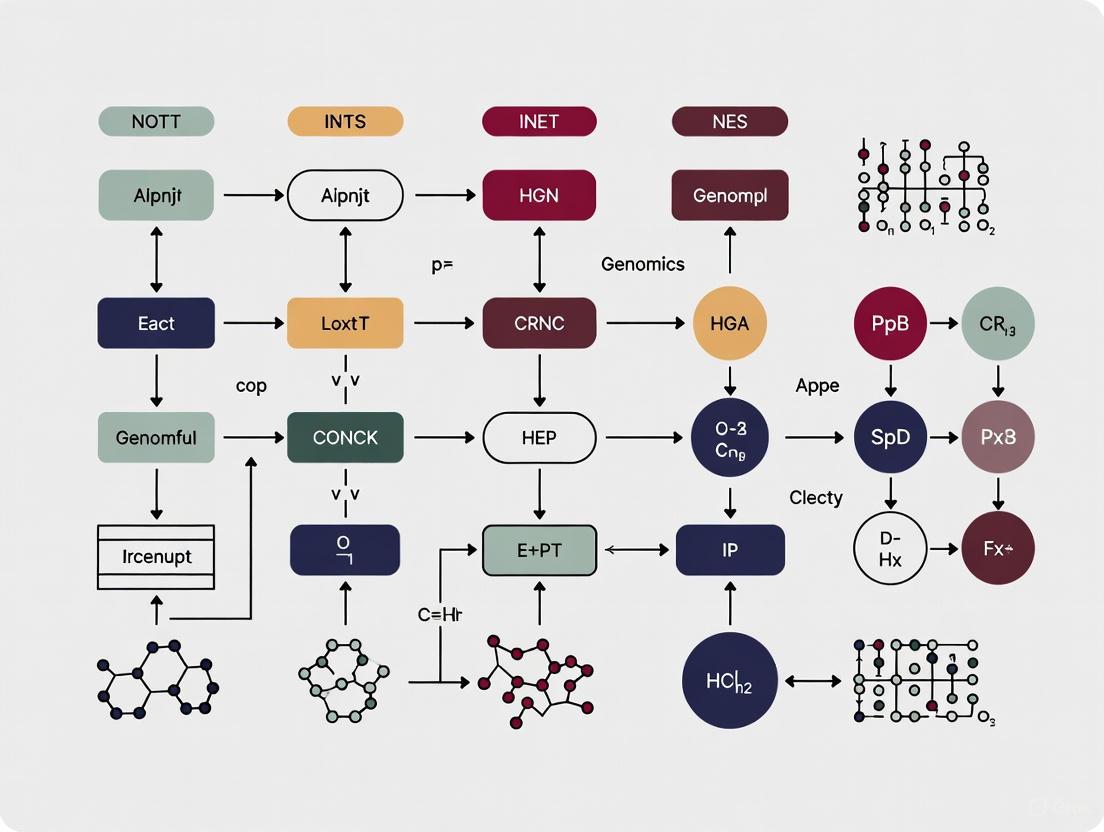

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for functional genomics in model systems:

Key Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics

CRISPR-Cas technologies have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling precise genetic manipulations in various model organisms [2]. The development of innovative tools has dramatically expanded the functional genomics toolkit:

- Base editors: Enable single-nucleotide modifications without double-strand breaks

- Prime editors: Offer precision edits without double-strand breaks

- CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa): Elucidate mechanisms of gene regulation

- MIC-Drop and Perturb-seq: Increase screening throughput in vivo

The following diagram illustrates the CRISPR-based functional screening workflow:

Advanced Multi-Omic Single-Cell Technologies

Recent methodological advances have enabled more sophisticated functional genomics approaches. Single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) represents a breakthrough technology that simultaneously profiles up to 480 genomic DNA loci and genes in thousands of single cells [3]. This enables accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated gene expression changes, addressing a critical limitation in linking precise genotypes to gene expression in their endogenous context [3].

SDR-seq methodology employs:

- Droplet-based partitioning of single cells with barcoding beads

- In situ reverse transcription with custom poly(dT) primers

- Multiplexed PCR amplification of both gDNA and RNA targets

- Separate library generation for gDNA and RNA with optimized sequencing

This technology has been successfully scaled to detect hundreds of gDNA and RNA targets simultaneously, with 80% of all gDNA targets detected with high confidence in more than 80% of cells across various panel sizes [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted gene knockout via DSB and NHEJ repair | Gene function validation, disease modeling [2] |

| Base Editors | Single-nucleotide modifications without DSBs | Precise modeling of point mutations [2] |

| Prime Editors | Targeted insertions and deletions without DSBs | Precise genome engineering [2] |

| Guide RNA Libraries | Target Cas proteins to specific genomic loci | High-throughput screens [2] |

| SDR-seq Reagents | Simultaneous DNA and RNA profiling in single cells | Linking genotypes to phenotypes at single-cell resolution [3] |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics Kits | Integrated transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic profiling | Comprehensive cellular characterization [3] |

Applications and Case Studies

National and International Initiatives

Large-scale genomic medicine initiatives demonstrate the translational potential of functional genomics. The 2025 French Genomic Medicine Initiative (PFMG2025) has integrated genome sequencing into clinical practice at a nationwide level, focusing on rare diseases, cancer genetic predisposition, and cancers [4]. As of December 2023, this initiative had delivered 12,737 results for rare disease/cancer genetic predisposition patients with a diagnostic yield of 30.6%, and 3,109 results for cancer patients [4].

The All of Us Research Program in the United States has continued to expand its genomic offerings, with the spring 2025 release increasing participants with genotype arrays to more than 447,000, including 414,000 with whole-genome sequencing [5]. This program has enabled a broad spectrum of genomic research, producing over 700 peer-reviewed publications, including more than 130 genomics-focused studies [5].

DOE JGI 2025 Functional Genomics Awards

The Department of Energy's Joint Genome Institute (JGI) has selected 11 researchers for 2025 functional genomics projects, representing diverse applications across bioenergy, agriculture, and environmental sustainability [6]:

Table 3: Select 2025 JGI Functional Genomics Projects

| Principal Investigator | Institution | Project Focus | Functional Genomics Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hao Chen | Auburn University | Drought tolerance and wood formation in poplar trees | Transcriptional regulatory network mapping using DAP-seq |

| Todd H. Oakley | UC Santa Barbara | Cyanobacterial rhodopsins for broad-spectrum energy capture | Machine learning prediction of protein function from gene sequences |

| Aaron M. Rashotte | Auburn University | Cytokinin signaling to prolong photosynthesis and boost yield | Machine learning analysis of gene expression data |

| Setsuko Wakao | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | Silica biomineralization in diatoms for biomaterials | DNA synthesis and sequencing to map biomineralization regulation |

Industry Applications and Biotech Innovation

UK-based biotech companies exemplify the commercial application of functional genomics:

- CardiaTec Biosciences: Applies functional genomics to cardiovascular drug discovery, using computational and experimental approaches to dissect the genetic architecture of heart disease [1]

- Nucleome Therapeutics: Focuses on decoding the "dark genome" to discover novel drug targets for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [1]

- Constructive Bio: Engineers cells into sustainable biofactories through whole genome writing and genetic code expansion [1]

- PrecisionLife: Uses AI-driven functional genomics platforms to identify complex biological drivers of chronic diseases [1]

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of functional genomics in model systems will be shaped by several converging technologies and challenges. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly indispensable for analyzing complex genomic datasets, with applications in variant calling, disease risk prediction, and drug discovery [7]. The integration of multi-omics approaches—combining genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—provides a more comprehensive view of biological systems than genomic analysis alone [7].

Critical challenges that remain include:

- Data management and analysis of massive genomic datasets

- Ensuring equitable access to genomic services across regions

- Harmonizing global ethical standards for genomic data use

- Improving predictive models of gene function and variant impact

Functional genomics in model systems continues to be essential for translating genomic discoveries into mechanistic understanding and therapeutic applications. As technologies advance and datasets grow, the field promises to increasingly illuminate the functional elements of genomes across diverse biological contexts and model systems.

Model organisms are indispensable tools in functional genomics and drug discovery, enabling the systematic study of gene function within a whole-organism context. Established models including zebrafish (Danio rerio), the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), and the nematode worm (Caenorhabditis elegans) provide a powerful combination of genetic tractability, experimental throughput, and physiological relevance. Recent advances are expanding the model organism repertoire to include emerging systems with unique biological attributes. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the key characteristics, experimental methodologies, and applications of these systems, framing their use within the overarching goals of functional genomics research aimed at understanding the genetic basis of biological processes and human disease.

Functional genomics seeks to bridge the gap between genome sequences and biological function, defining the roles of genes and their products in cellular and organismal processes. Model organisms are the experimental pillars of this discipline. The strategic selection of a model is paramount and is guided by the specific research question, weighing factors such as genetic homology to humans, physiological complexity, cost, throughput, and ethical considerations [8] [9] [10].

The core principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal research have accelerated the development and adoption of non-mammalian models [8]. These organisms often permit experimental scales and approaches that are impractical in mammalian systems, facilitating high-throughput genetic and chemical screens that can rapidly advance target identification and drug discovery [10].

Comparative Analysis of Established Model Organisms

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of the primary model organisms discussed in this guide, highlighting key parameters relevant to experimental design in functional genomics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Model Organisms

| Characteristic | C. elegans | D. melanogaster | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Similarity to Humans | ~40% genes have human orthologs; ~65% homologous to human disease genes [8] [10] | ~75% of human disease genes have a fly ortholog [8] [10] | ~84% of human disease-related genes share a zebrafish counterpart [9] [11] |

| Generation Time | ~3 days at 25°C [10] | ~10 days at 25°C [10] | ~3 months [10] |

| Husbandry Cost | Very low [8] [10] | Low [8] [10] | Low animal costs [10] |

| Key Advantages | Transparent body; complete cell lineage and connectome; high-throughput RNAi screening; can be frozen [8] [10] | Complex anatomy; conserved physiological processes; extensive genetic toolkit [8] [10] | Transparent embryos; vertebrate physiology; amenability to high-throughput screening [9] [10] |

| Primary Limitations | Simple anatomy; cuticle may limit drug absorption [9] [10] | Inability to freeze stocks; life cycle longer than worms [8] [10] | Lack of some human organs (e.g., lungs, mammary glands) [9] |

Established Model Organisms: Applications and Protocols

Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematode Worm)

Applications in Functional Genomics: C. elegans is a powerful system for in vivo functional genomics, particularly for uncovering genetic networks through forward genetic screens and genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) approaches. Its utility extends to studying taxonomically restricted genes, such as the LIN-15B-domain-encoding gene family, which offers insights into gene emergence and adaptation within a lineage [12]. Research on genes like ivph-3 and gon-14 in C. elegans and C. briggsae provides a paradigm for studying how new genes integrate into essential biological processes and regulatory networks [12].

Detailed Protocol: Genome-wide RNAi Screening by Feeding

- Objective: To identify genes involved in a specific phenotype (e.g., multivulva, sterility, locomotion defect) on a genome-wide scale.

- Principle: Worms are fed E. coli strains expressing double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) homologous to a target gene, which induces systemic RNAi and knocks down gene function [10].

- Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Obtain a comprehensive RNAi feeding library (e.g., the Ahringer library) covering most of the ~20,000 C. elegans genes, arrayed in multi-well plates.

- Bacterial Induction: Grow the specific E. coli HT115(DE3) RNAi clone in liquid culture with antibiotics. Induce dsRNA expression by adding IPTG.

- Seed Assay Plates: Spot the induced bacteria onto NGM agar plates containing IPTG and ampicillin. Allow lawns to grow.

- Synchronize Worms: Use a hypochlorite treatment to isolate eggs from a gravid adult population, generating a synchronized L1 larval stage.

- Screen Execution: Transfer a small number of synchronized L1 larvae to each RNAi assay plate.

- Phenotypic Scoring: Incubate plates at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 20°C or 25°C) and score for the phenotype of interest over several days, comparing to control RNAi (e.g., empty vector).

- Downstream Analysis: Hit validation via secondary screens, complementation tests with known mutants, and molecular characterization of the affected pathway.

Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit Fly)

Applications in Functional Genomics: Drosophila is exceptionally suited for modeling human genetic diseases and understanding conserved signaling pathways. Its complex anatomy allows for the study of neurobiology, immunology, and host-pathogen interactions. The "diagnostic strategy" is a notable application, where human gene variants are tested for their ability to rescue the phenotype of a fly gene knockout, thereby validating the pathogenicity of the human variant [10].

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout

- Objective: To generate a stable loss-of-function mutation in a specific gene.

- Principle: The Cas9 nuclease, guided by a gene-specific single-guide RNA (sgRNA), creates a double-strand break in the genomic DNA, which is repaired by error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), leading to insertion/deletion mutations.

- Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to a 5'-NGG Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) in an early exon of the target gene. Tools like FlyCRISPR are recommended.

- Vector Construction: Clone the sgRNA sequence into a Drosophila expression vector (e.g., pU6-BbsI-chiRNA).

- Embryo Injection: Co-inject the sgRNA plasmid and a plasmid expressing Cas9 (or Cas9 protein with in vitro transcribed sgRNA) into pre-blastoderm embryos of a recipient strain.

- Establishment of Stable Lines: Cross the surviving injected embryos (G0) to balancer flies. Screen the progeny (G1) for evidence of mutagenesis (e.g., by loss of a marker phenotype or PCR). Cross individual G1 flies to establish independent mutant lines.

- Molecular Validation: Isolate genomic DNA from candidate lines and perform PCR amplification of the target locus, followed by sequencing to confirm the nature of the mutation.

Danio rerio (Zebrafish)

Applications in Functional Genomics: Zebrafish bridge the gap between invertebrate models and mammalian physiology. Their external development and optical transparency are ideal for live imaging of developmental processes, cancer progression, and infection. A major application is phenotype-based drug screening, where zebrafish disease models are used to identify small molecules that modify the disease phenotype, with subsequent target deconvolution [10] [11]. They are also increasingly used to validate and study mutations in human genes implicated in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders [11].

Detailed Protocol: Phenotype-Based Chemical Screen

- Objective: To identify small molecules that suppress or enhance a specific, measurable phenotype (e.g., neural degeneration, developmental defect, behavior).

- Principle: Embryos carrying a genetic mutation or exposed to a chemical teratogen are treated with compounds from a chemical library and assessed for phenotypic rescue or exacerbation.

- Procedure:

- Model Generation: Use a stable mutant line or create a transient knockdown (e.g., with morpholinos) that produces a robust and scorable phenotype. Alternatively, establish a teratogen-induced model.

- Synchronized Embryo Production: Set up timed matings of adult fish to collect a large batch of embryos at the 1-4 cell stage.

- Compound Dispensing: Use a liquid handler to aliquot compounds from a library (e.g., FDA-approved drugs, diverse synthetic compounds) into 96-well plates.

- Compound Exposure: At a defined developmental stage (e.g., shield stage), dechorionate embryos if necessary and distribute one embryo per well into the compound solution.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Incubate the plates and score the phenotype at predetermined timepoints. Scoring can be manual (using microscopy) or automated (using high-content imaging systems).

- Hit Identification: Compounds that significantly reverse the disease phenotype are classified as "hits" for further validation.

- Downstream Analysis: Hit validation in dose-response curves, assessment of toxicity, and investigation of the mechanism of action through transcriptomics, proteomics, or genetic interaction studies.

Visualization of a Functional Genomics Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, iterative workflow for functional genomics research in model organisms, integrating genetic and chemical screening approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful functional genomics research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and resources. The table below details key solutions for the featured model organisms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Model Organisms

| Reagent / Resource | Organism | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNAi Feeding Library | C. elegans | Enables genome-wide loss-of-function screens. Bacteria expressing dsRNA for a target gene are fed to worms, inducing systemic RNAi [10]. |

| Million Mutations Project Library | C. elegans | A curated library of ~2007 mutagenized strains, providing an average of 8 non-synonymous mutations per gene for forward genetic screening [8]. |

| Balancer Chromosomes | D. melanogaster | Engineered chromosomes containing inversions and dominant markers used to maintain lethal mutations in stable breeding stocks and identify heterozygous individuals. |

| tsCRISPR Tools | D. melanogaster | Tissue-specific CRISPR systems that allow for spatially and temporally controlled gene editing, enabling in vivo functional screens in specific cell types [8]. |

| Morpholinos | D. rerio | Stable, antisense oligonucleotides that block mRNA translation or splicing. Used for transient, rapid gene knockdown in early embryonic stages [10]. |

| Chemical Libraries (e.g., FDA-approved) | All | Collections of bio-active small molecules used in phenotype-based screens to identify compounds that modify a disease-relevant phenotype [10]. |

Emerging Model Systems

Beyond the classic models, new systems are gaining prominence due to unique biological features. The plant genus Plantago is an emerging model for functional genomics in areas such as vascular biology, stress physiology, and medicinal biochemistry [13] [14]. Several Plantago species possess easily accessible vascular tissues, a short life cycle (6-10 weeks to flower), sequenced genomes, and established CRISPR-Cas9 protocols, making them particularly valuable for studying systemic signaling and environmental adaptation [13]. Their established use in diverse fields like ecology and agriculture underscores their versatility as a model system [14].

Zebrafish, Drosophila, and C. elegans form a robust triad of model organisms that collectively address a wide spectrum of questions in functional genomics and drug discovery. Their complementary strengths—from the unparalleled genetic and cellular tractability of C. elegans and the disease modeling prowess of Drosophila to the vertebrate physiology and screening potential of zebrafish—make them indispensable for linking genes to function. The continuous refinement of genomic tools, such as CRISPR, and the rise of emerging models like Plantago, ensure that this ecosystem will continue to drive innovation, deepen our understanding of complex biological systems, and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

The relationship between an organism's genetic makeup (genotype) and its observable characteristics (phenotype) represents one of the most fundamental challenges in modern biology. Despite the molecular revolution that has enabled rapid, cost-effective genome sequencing, predicting phenotypic outcomes from genetic data alone remains notoriously difficult. This challenge is particularly acute in clinical and research settings, where the inability to reliably connect genetic variants to their functional consequences creates a "diagnostic odyssey" for patients and researchers alike. The genotype-phenotype (GP) mapping is neither injective nor functional—meaning the same genotype can produce different phenotypes, and the same phenotype can arise from different genotypes—adding layers of complexity to predictive efforts [15].

Functional genomics in model organisms provides a powerful framework for addressing this challenge. By leveraging controlled genetic backgrounds and standardized environmental conditions, researchers can systematically dissect the mechanisms bridging genetic variation to phenotypic expression. Recent technological advances in high-throughput sequencing, massively parallel genetics, and machine learning are now accelerating our ability to map these relationships with unprecedented resolution [16] [17]. This whitepaper examines the current state of GP mapping technologies, methodologies, and analytical frameworks that are collectively helping to end the diagnostic odyssey by transforming our ability to predict phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information.

Current Challenges in Genotype-Phenotype Mapping

Data Heterogeneity and Standardization

The immense value of large-scale genotype and phenotype datasets for current and future studies is well-recognized, particularly for advancing crop breeding, yield improvement, and overall agricultural sustainability. However, integrating these datasets from heterogeneous sources presents significant challenges that hinder their effective utilization. The Genotype-Phenotype Working Group of the AgBioData Consortium has identified critical gaps in current infrastructure, including the need for additional support for archiving new data types, community standards for data annotation and formatting, resources for biocuration, and improved analysis tools [18]. Similar challenges plague microbial research, where errors in gene annotation, omissions due to assumptions about genetic elements, and inconsistencies in metadata standardization complicate comparative analyses [19].

Biological Complexity

The relationship between genotype and phenotype is profoundly complicated by biological phenomena including epistasis (gene-gene interactions), pleiotropy (single genes affecting multiple traits), dominance, and environmental influences [15]. Additionally, non-genetic heterogeneity introduces further complexity through mechanisms such as bet-hedging (where a fixed genotype produces multiple phenotypes stochastically) and phenotypic plasticity (where environment determines phenotype for a given genotype) [15]. These factors collectively ensure that the GP mapping is rarely straightforward, with phenotypic changes sometimes arising without genetic change through epigenetic modifications or other non-heritable mechanisms that generate phenotypic heterogeneity.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Genotype-Phenotype Mapping

| Challenge Category | Specific Issues | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Infrastructure | Inconsistent sample identifiers; Lack of community standards; Distributed data repositories | Hinders data integration and reuse; Limits interoperability |

| Biological Complexity | Epistasis; Pleiotropy; Phenotypic plasticity; Environmental influences | Reduces predictive accuracy; Complicates mechanistic understanding |

| Technical Limitations | Incomplete genome annotation; Measurement noise; Scaling limitations | Introduces errors; Restricts comprehensiveness of studies |

Technological Advances Enabling High-Resolution GP Mapping

High-Throughput Sequencing and Genotyping Technologies

Sequencing technology has evolved rapidly from early Sanger methods to high-throughput massive parallel sequencing that enables whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and transcriptome sequencing. Current platforms include short-read sequencing (Next-Generation Sequencing, NGS) such as Illumina, and long-read Third Generation Sequencing (3GS) including PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [18]. These advances have enabled various strategies for genotyping, including:

- Skim sequencing: A low-coverage WGS approach for cost-effective genotyping [18]

- Target enrichment sequencing: Investigation of specific genomic elements via pre-defined probe sequences [18]

- Exome sequencing: Focuses on protein-coding regions of genes [18]

- Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) and restriction site-associated DNA marker sequencing (RAD-seq): Cost-effective sequencing strategies for shearing genomes via restriction enzymes [18]

Massively Parallel Functional Genomics

The arrival of massively parallel sequencing technologies has enabled the development of deep mutational scanning assays capable of scoring comprehensive libraries of genotypes for fitness and various phenotypes in massively parallel fashion [16]. These approaches include:

- Phage display: Allows biochemical phenotypes of polypeptides to be traced back to their coding DNA sequence by fusing the polypeptide of interest to a viral coat protein [16]

- EMPIRIC (Extremely Methodical and Parallel Investigation of Randomized Individual Codons): Enables direct measurement of fitness impacts of all mutations in bulk by tracking genotype frequencies during laboratory propagation [16]

- Arrayed mutant collections: Large sets of pure cultures of distinct mutant strains stored in formats compatible with high-throughput liquid handling systems [19]

- Pooled mutant collections: Mixed cultures comprising many mutant strains that can be screened simultaneously [19]

Table 2: High-Throughput Technologies for GP Mapping

| Technology | Primary Application | Key Features | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning | Comprehensive mutation effects analysis | Scores mutant libraries for fitness and phenotypes in parallel | Human WW domain variants; Hsp90 mutagenesis [16] |

| RB-TnSeq (Randomly Barcoded Transposon Sequencing) | Gene function identification | Random transposon insertion across genome followed by phenotypic screening | Loss-of-function mutagenesis in microbes [19] |

| CRISPRi-seq | Gene function analysis | Uses CRISPR interference to lower gene expression followed by screening | Identification of essential genes [19] |

| Dub-seq (Dual-Barcoded Shotgun Expression Library Sequencing) | Gene function discovery | Expresses genomic DNA fragments in host organism | Gain-of-function mutagenesis [19] |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Deep Mutational Scanning Workflow

Deep mutational scanning represents a powerful approach for empirically characterizing genotype-phenotype relationships. The experimental workflow begins with the design and synthesis of a comprehensive mutant library, often targeting specific genes or regulatory regions. This library is then introduced into a model system appropriate for the phenotype of interest. After applying relevant selection pressures—which might include drug treatment, environmental stress, or nutritional limitations—researchers sequence the pre- and post-selection populations using high-throughput methods [16]. By quantifying the enrichment or depletion of specific variants, researchers can calculate fitness effects or measure specific phenotypic impacts. This approach has revealed fundamental insights, including the bimodal distribution of fitness effects (with mutations typically being either strongly deleterious or nearly neutral) and the position-specific nature of mutational tolerance [16].

Machine Learning-Enhanced GP Mapping

Recent advances in machine learning are transforming GP mapping by enabling the modeling of complex, non-linear relationships that traditional methods miss. The G-P Atlas framework exemplifies this approach with its two-tiered architecture [17]. First, a denoising phenotype-phenotype autoencoder learns a compressed, efficient encoding of phenotypic data, capturing the underlying relationships between traits. Second, a separate network maps genotypic data into this learned latent space. This approach simultaneously models multiple phenotypes and genotypes, captures non-linear relationships, operates efficiently with limited biological data, and maintains interpretability to identify causal genetic variants [17]. When applied to both simulated and empirical datasets (including an F1 cross between two budding yeast strains), this framework successfully predicted multiple phenotypes from genetic data and identified causal genes—including those acting through non-additive interactions that conventional approaches often miss [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Arrayed Mutant Collections | Ordered libraries of distinct mutant strains | High-throughput phenotypic screening; Direct genotype-phenotype links without tracking [19] |

| DNA Barcodes | Short, unique DNA sequences introduced into strains | Tracking strain abundance in pooled experiments; Competitive fitness assays [19] |

| CRISPRi Libraries | Designed guide RNA collections for targeted gene suppression | Loss-of-function screens; Essential gene identification [19] |

| Dual-Barcoded Expression Libraries | Genomic DNA fragments with identifying barcodes | Gain-of-function screens; Gene discovery [19] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Multi-Modal Data Integration

The integration of diverse data types represents a promising frontier in GP mapping. Yale researchers recently demonstrated that machine learning applied to ordinary tissue images can reveal hidden patterns predictive of genetic variants, gene expression, and even chronological age [20]. Their approach, which analyzed histology slides, genetic information, and RNA data from 838 donors across 12 tissue types, found that the shape, size, and structure of cell nuclei carry substantial biological information. This multi-modal approach successfully identified 906 points in the human genome strongly associated with nuclear appearance across different tissues, revealing connections between nuclear shape and gene activity that were previously invisible to traditional methods [20].

Standardization and Data FAIRness

Making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) requires concerted efforts among all parties involved in data generation and curation [18]. The AgBioData Consortium has emerged as a key player in these efforts, working to define community-based standards, expand stakeholder networks, develop educational materials, and create a sustainable ecosystem for genomic, genetic, and breeding databases [18]. Similar initiatives are underway in microbial research, where researchers advocate for centralized, automated systems to maintain current genome annotations and standardized metadata collection [19]. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are expected to play increasingly important roles in maintaining accurate, up-to-date annotations that reflect the most recent research findings.

The journey to definitively link genotype to phenotype represents one of the most important challenges in modern biology, with profound implications for basic research, clinical medicine, and biotechnology. While significant hurdles remain—including biological complexity, data heterogeneity, and technical limitations—recent advances in high-throughput technologies, functional genomics methodologies, and computational approaches are rapidly accelerating progress. The integration of massively parallel experiments with sophisticated machine learning frameworks like G-P Atlas provides a glimpse into the future of GP mapping, where predictive models account for the complex, non-linear interactions that characterize living systems. As these tools become more sophisticated and accessible, and as data standardization efforts mature, we move closer to ending the diagnostic odyssey—transforming our ability to predict phenotypic outcomes from genetic information and ultimately enabling more precise interventions across medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

The Model Organism Screening Center (MOSC) Framework

The Model Organism Screening Center (MOSC) represents a critical component of the modern functional genomics landscape, enabling the systematic investigation of gene function and variant pathogenicity. Established as part of the National Institutes of Health's Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), the MOSC framework bridges the divide between clinical genomics and biological validation [21]. Functional genomics integrates genome-wide technologies, computational modeling, and laboratory validation to systematically investigate the molecular mechanisms driving human disease [22]. In this context, the MOSC provides the essential experimental platform for moving beyond variant identification to functional characterization, using complementary model organisms to investigate whether rare variants contribute to disease pathogenesis [23].

The fundamental premise of the MOSC approach rests on the high degree of evolutionary conservation between humans and the selected model organisms. Despite morphological differences, fundamental biological mechanisms and genes are remarkably well conserved, enabling researchers to "model" human disease conditions in these systems [23]. This conservation, combined with the cost efficiency, short life cycles, and sophisticated genetic tools available in these organisms, makes them ideal for high-throughput functional genomics investigations of rare variants [24].

Organizational Structure and Leadership

The MOSC operates as a collaborative network with distributed expertise across multiple leading institutions. The current structure comprises two complementary centers:

- BCM-UO MOSC: Led by Baylor College of Medicine in collaboration with the University of Oregon, with leadership including Hugo J. Bellen, Michael F. Wangler, Shinya Yamamoto, Monte Westerfield, and John Postlethwait [23].

- WashU MOSC: Led by Washington University in St. Louis under the direction of Lilianna Solnica-Krezel, Tim Schedl, Dustin Baldridge, and Stephen C. Pak [23].

This collaborative structure leverages specialized expertise across different model organism systems while maintaining consistent standards and workflows. The MOSC functions as an integral component of the broader UDN, which also includes Clinical Sites, a Sequencing Core, a Metabolomics Core, and a Coordinating Center [21].

The MOSC Workflow: From Clinical Presentation to Functional Validation

The MOSC operational workflow represents a systematic approach to functional validation of candidate variants, beginning with patient identification and culminating in experimental data generation.

Detailed Process Description

The workflow initiates when a diagnosis cannot be reached through standard clinical, genetic, and metabolomic workups [23]. UDN Clinical Sites submit candidate genes/variants to the MOSC along with clinical descriptions of the participant's condition. The MOSC then performs comprehensive bioinformatics analyses using the MARRVEL tool (Model organism Aggregated Resources for Rare Variant ExpLoration) and other resources to aggregate existing information on the human gene/variant and its model organism orthologs [23] [21].

Simultaneously, the MOSC engages in "matchmaking" – identifying other individuals with similar genotypes and phenotypes in other cohorts [23]. Once a variant is prioritized, MOSC investigators design customized experimental plans tailored to the specific gene, variant, and patient presentation, selecting the most appropriate model organism system [24]. These functional studies provide evidence regarding variant pathogenicity that can support diagnosis and reveal underlying disease mechanisms.

Model Organisms in the MOSC Framework

The MOSC employs three principal model organisms that provide complementary strengths for functional genomics research. The selection of these specific organisms is based on their evolutionary conservation, genetic tractability, and practical experimental considerations.

Table 1: Model Organisms in the MOSC Framework

| Organism | Scientific Name | Key Characteristics | Experimental Strengths | Conservation with Humans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit Fly | Drosophila melanogaster | Short life cycle (10-12 days), low maintenance costs, sophisticated genetic tools [23] | High-throughput screening, "humanizing" genes to assess variant consequences [21] | ~75% of human disease genes have functional fly orthologs [24] |

| Nematode Worm | Caenorhabditis elegans | Transparent body, invariant cell lineage, simple nervous system [25] | Cellular-level analysis, ease of imaging, complete connectome mapped | Many conserved signaling pathways and gene networks [25] |

| Zebrafish | Danio rerio | Vertebrate system, transparent embryos, ex utero development [23] | Organ-level analysis, drug screening, conservation of vertebrate systems | ~70% of human genes have at least one obvious zebrafish ortholog [24] |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

The MOSC employs standardized experimental protocols to ensure reproducibility and reliability of functional genomics data. The specific methodologies vary by model organism but share common principles of genetic manipulation and phenotypic analysis.

Standardized Protocol Reporting

Effective experimental protocols require comprehensive documentation to ensure reproducibility. Key data elements for reporting experimental protocols include [26]:

- Study design: Hypothesis, experimental unit, sample size

- Experimental procedures: Step-by-step workflow with timing and specifications

- Reagents and equipment: Catalog numbers, lot numbers, specific parameters

- Sample characteristics: Source, preparation method, inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Data acquisition: Instruments, software, settings, raw data processing

- Quality assurance: Controls, calibration, normalization methods

Genetic Manipulation Techniques

The MOSC employs cutting-edge genetic technologies to model human variants, including:

- Gene disruption: Using CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi to create loss-of-function alleles

- Humanization: Replacing the model organism gene with the human version to assess functional consequences of novel variants [21]

- Variant-specific modeling: Introducing patient-specific mutations into the endogenous model organism gene or human transgene

- Rescue experiments: Expressing wild-type or mutant human genes in model organism null backgrounds

Phenotypic Assessment Methods

Comprehensive phenotypic analysis forms the core of MOSC investigations:

- Developmental phenotypes: Survival, growth, morphological defects

- Behavioral assays: Locomotion, learning, sensory function

- * Cellular analysis*: Imaging of subcellular localization, tissue architecture

- Molecular profiling: Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics

- Physiological measurements: Electrophysiology, metabolic function

The MARRVEL Bioinformatics Platform

The MARRVEL (Model organism Aggregated Resources for Rare Variant ExpLoration) tool represents a critical bioinformatics component of the MOSC framework. This powerful web-based platform integrates human and model organism genetic resources to facilitate functional annotation of the human genome [23] [21].

MARRVEL enables simultaneous searching of multiple databases, including:

- Human genetics databases (ExAC, gnomAD, OMIM)

- Model organism databases (FlyBase, WormBase, ZFIN)

- Protein interaction and expression databases

- Variant annotation resources

This integrated approach allows researchers to quickly gather comprehensive information about gene and variant function across species, significantly accelerating the variant prioritization process [23]. The tool is publicly available at marrvel.org and is continuously updated with new data sources and functionalities.

The MOSC generates and distributes valuable research reagents that support the wider scientific community. These resources enable further mechanistic studies and diagnostic applications beyond the immediate scope of the UDN.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in the MOSC Framework

| Reagent Type | Description | Function | Distribution Resource |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant Lines | Model organism strains with loss-of-function alleles | Provide biological models for gene function studies | Organism-specific stock centers (CGC, BDSC, ZIRC) [24] |

| Humanized Lines | Strains with human gene knock-ins | Enable assessment of human variant effects in vivo | Organism-specific stock centers [24] |

| Expression Constructs | Vectors for wild-type and mutant human cDNA | Allow functional complementation and rescue experiments | Addgene and institutional repositories [26] |

| Protocol Documentation | Standardized experimental procedures | Ensure reproducibility across laboratories | Public repositories and publications [26] |

Outcomes and Impact

The MOSC framework has demonstrated significant impact in rare disease diagnosis and gene discovery. During Phase I of the UDN (2015-2018), the MOSC processed 239 variants in 183 genes from 122 probands [24]. In-depth biological data for 19 genes led directly to diagnosis, with studies for additional genes ongoing [24].

The economic efficiency of this approach is notable, with an estimated cost of approximately $150,000 per gene discovery when accounting for both successful diagnoses and studies of other candidate genes that did not yield diagnoses [24]. This cost includes the generation of valuable community resources such as mutant lines and bioinformatic tools.

The benefits of MOSC investigations extend beyond individual diagnoses to include:

- Ending diagnostic odysseys for patients and families

- Enabling prenatal diagnosis options

- Facilitating the formation of patient advocacy groups

- Providing insights into common disease mechanisms through rare disease studies

- Generating tools and reagents for broader scientific community [24]

Future Directions in Model Organism Functional Genomics

The MOSC framework continues to evolve with advancements in functional genomics technologies. Future directions include:

- Integration of multi-omics approaches: Combining transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data to provide comprehensive mechanistic insights [27] [22]

- Spatial functional genomics: Mapping genetic effects within tissue context using emerging spatial technologies [22]

- High-content phenotyping: Implementing automated, quantitative morphological and behavioral analyses

- Network biology: Placing genes within regulatory and interaction networks to understand system-level effects [22]

- Therapeutic screening: Using validated models for small molecule and genetic therapeutic testing

The success of the MOSC has led to advocacy for the establishment of a permanent Model Organisms Network (MON) to be funded through NIH grants, family groups, philanthropic organizations, and industry partnerships [24]. This would ensure the continued application of model organism functional genomics to rare disease diagnosis and discovery.

From Gene Discovery to Understanding Common Disease Mechanisms

The transition from gene discovery to elucidating common disease mechanisms represents a critical pathway in modern biomedical research. This whitepaper examines the integrated approaches of functional genomics and systems biology that enable researchers to move beyond mere genetic associations toward comprehensive understanding of disease pathophysiology. By leveraging high-throughput technologies including next-generation sequencing, mass spectrometry, and advanced computational analyses, researchers can now systematically characterize how genes and their products interact within complex biological networks. These approaches are particularly powerful when applied within model organism systems, where controlled genetic manipulation allows for precise dissection of molecular pathways relevant to human disease. The framework presented here provides both methodological guidance and conceptual foundation for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to translate genetic findings into mechanistic insights with therapeutic potential.

Functional genomics represents a paradigm shift from traditional gene-by-gene approaches to genome-wide analyses that comprehensively characterize the functions and interactions of genes and proteins [28]. This field has emerged through the development of high-throughput technologies that enable simultaneous investigation of multiple molecular layers, including DNA mutations, epigenetic modifications, transcription, translation, and protein-metabolite interactions. The core premise of functional genomics is that understanding biological systems requires integrated analysis of these various processes rather than isolated examination of individual components.

The application of functional genomics to disease mechanism research has been particularly transformative for understanding complex traits and common diseases. Where initial genome-wide association studies (GWAS) successfully identified statistical links between genetic variants and diseases, functional genomics provides the tools to determine how these variants actually influence biological function and disease manifestation. By combining genomic data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles, researchers can construct interactive network models that reveal how genetic perturbations propagate through biological systems to produce phenotypic outcomes.

Model organisms serve as indispensable components in this research paradigm, providing experimentally tractable systems in which to validate and characterize disease mechanisms suggested by human genetic studies. The conservation of fundamental biological processes across species allows researchers to manipulate genetic elements in model organisms and observe resulting phenotypic consequences with precision control that would be impossible in human subjects. This integrated approach—moving from human genetic discoveries to mechanistic studies in model systems and back again—has become the gold standard for elucidating common disease mechanisms.

Core Methodologies and Experimental Frameworks

High-Throughput Genomic Technologies

Next-Generation Sequencing Applications

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized our ability to study the various genetic and epigenetic mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis with unprecedented detail and specificity [28]. Three main NGS platforms are widely used in functional genomics research: the Roche 454 platform, the Applied Biosystems SOLiD platform, and the Illumina Genome Analyzer and HiSeq platforms. More recently developed technologies such as Ion Torrent take advantage of semiconductor-sensing devices that directly transform chemical signals to digital information. These platforms have caused a dramatic drop in sequencing costs while simultaneously improving throughput, making large-scale genomic studies feasible.

The applications of NGS in functional genomics are diverse and powerful. RNA-Seq enables comprehensive profiling of transcriptomes, allowing researchers to analyze gene expression levels, transcript boundaries, intron/exon junctions, alternative splice variants, and non-coding RNA species. ChIP-Seq combines chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing to map genome-wide locations of transcription factor binding sites and histone modifications, providing insights into epigenetic regulation. Whole-genome sequencing facilitates identification of DNA mutations ranging from single-nucleotide polymorphisms to large structural variations. The enormous data generated by these approaches—currently up to 6 billion short reads or 600 gigabase per instrument run—has greatly enhanced our understanding of gene regulation and the role of genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in disease.

Table 1: Next-Generation Sequencing Applications in Functional Genomics

| Application | Key Information Obtained | Typical Read Depth | Primary Use in Disease Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq | Gene expression levels, splice variants, novel transcripts | 20-50 million reads/sample | Identify differentially expressed genes in diseased versus healthy tissues |

| ChIP-Seq | Transcription factor binding sites, histone modifications | 10-30 million reads/sample | Map epigenetic changes associated with disease states |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | SNPs, indels, structural variants | 30-60x coverage | Identify causal genetic variants in patient populations |

| Targeted Sequencing | Specific genes or regions of interest | 100-1000x coverage | Deep sequencing of disease-associated loci |

Functional Genomic Characterization Techniques

Beyond sequencing, functional genomics employs diverse experimental techniques to characterize gene function and regulation. DNA microarrays, while preceded by NGS technologies for some applications, continue to provide valuable biological information, particularly for gene expression profiling [28]. Microarrays consist of thousands of microscopic DNA spots bound to a solid surface, which hybridize with labeled nucleic acids from experimental samples. The amount of hybridization detected for each probe corresponds to the abundance of specific transcripts, enabling comparison of gene expression patterns between different cell types or conditions.

More recently, genome mapping technologies have emerged to address limitations in sequencing-based structural variant detection [29]. Electronic genome mapping enables precise detection of structural variations—including deletions, duplications, inversions, translocations, and insertions—that cannot be reliably identified using traditional sequencing methods, especially in repetitive and complex genomic regions. These structural variations play critical roles in the genetic basis of various diseases and phenotypic traits by impacting gene expression, regulatory elements, and protein function.

Novel approaches like DAP-Seq (DNA Affinity Purification sequencing) are being deployed to map transcriptional regulatory networks underlying important biological processes. For example, researchers are applying DAP-Seq to unravel the crosstalk in poplar's transcriptional regulatory network for drought tolerance and wood formation, with direct implications for understanding similar regulatory networks in human disease [6]. These functional characterization techniques provide critical data for building comprehensive models of gene regulation in health and disease.

Advanced Computational and Modeling Approaches

Systems Biology and Network Analysis

Systems biology approaches integrate information from various molecular processes to model interactive networks that regulate gene expression, cell differentiation, and cell cycle progression [28]. This methodology recognizes that biological functions emerge from complex interactions between multiple components rather than from linear pathways. By analyzing high-throughput genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data using network theory, researchers can identify key regulatory hubs and modules that play disproportionate roles in disease pathogenesis.

Cluster analysis is frequently employed to characterize genes with similar expression profiles that are likely to have related biological functions. For disease mechanism research, this approach can reveal coordinated molecular responses to pathological stimuli and identify disease-specific network perturbations. The resulting network models provide frameworks for understanding how discrete genetic variants can influence broader biological systems, helping to explain the mechanisms underlying polygenic diseases.

Generative Genomic Models

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced powerful new tools for functional genomics through generative genomic models. The Evo genomic language model exemplifies this approach by learning semantic relationships across prokaryotic genes to perform function-guided sequence design [30]. This model enables "semantic design"—a generative strategy that harnesses multi-gene relationships in genomes to design novel DNA sequences enriched for targeted biological functions.

The Evo model demonstrates the ability to leverage genomic context through an "autocomplete" function, where supplying appropriate genomic context as a prompt conditions the model to generate novel genes whose functions mirror those found in similar natural contexts [30]. This approach has been successfully applied to design functional toxin-antitoxin systems and anti-CRISPR proteins, including de novo genes with no significant sequence similarity to natural proteins. For disease research, such models offer the potential to generate novel genetic elements for probing disease mechanisms or designing therapeutic interventions.

Experimental Protocols for Key Functional Genomics Applications

RNA-Seq for Transcriptome Analysis in Disease Models

Principle: RNA sequencing provides a comprehensive, quantitative profile of the transcriptome, enabling identification of differentially expressed genes, alternative splicing events, and novel transcripts in disease models compared to controls.

Protocol:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from model organism tissues or cells using guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Assess RNA quality using an automated electrophoresis system (RIN > 8.0 required).

- Library Preparation: Deplete ribosomal RNA or enrich mRNA using poly-A selection. Fragment RNA to 200-300 bp fragments. Synthesize cDNA using random hexamer priming. Add sequencing adapters with unique molecular identifiers to correct for amplification bias.

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on Illumina platform (minimum 30 million 150 bp paired-end reads per sample).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control: FastQC for read quality, MultiQC for batch effects

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using STAR aligner

- Quantification: Generate gene-level counts using featureCounts

- Differential expression: Analyze using DESeq2 or edgeR with false discovery rate (FDR) correction

- Functional enrichment: GSEA for pathway analysis, clusterProfiler for GO terms

Troubleshooting Notes: For model organisms with less complete annotations, consider using a de novo transcriptome assembly approach with Trinity followed by differential expression analysis with Salmon and Sleuth. Batch effects can be minimized using randomized block designs and removed computationally with ComBat.

ChIP-Seq for Epigenetic Regulation Studies

Principle: Chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with sequencing identifies genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors or histone modifications, revealing epigenetic regulatory mechanisms in disease.

Protocol:

- Cross-linking and Cell Lysis: Treat model organism cells or tissues with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to cross-link protein-DNA complexes. Quench with 125 mM glycine. Lyse cells and isolate nuclei.

- Chromatin Shearing: Sonicate chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments using a focused ultrasonicator. Confirm fragment size by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with antibody against target protein/histone modification (5 μg per reaction). Use protein A/G magnetic beads for capture. Include matched IgG control.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and prepare sequencing libraries using ThruPLEX DNA-Seq kit. Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 20 million reads).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Peak calling: MACS2 for significant enrichment regions

- Motif analysis: HOMER for de novo and known motif discovery

- Differential binding: diffBind for condition-specific changes

- Integration: Overlap with RNA-Seq data using ChIP-Enrich

Critical Considerations: Antibody validation is essential—use knockout controls if available. Spike-in controls (e.g., Drosophila chromatin) enable normalization between conditions. For histone modifications, consider using a panel of antibodies to comprehensively map chromatin states.

CRISPR-Based Functional Screening in Model Organisms

Principle: Genome-scale CRISPR screens enable systematic identification of genes contributing to disease-relevant phenotypes in model organisms.

Protocol:

- Library Design: Design sgRNAs targeting all annotated genes (typically 4-6 guides/gene) plus non-targeting controls. Use optimized sgRNA design tools (CRISPick, CHOPCHOP).

- Virus Production: Clone sgRNA library into lentiviral vector. Produce high-titer lentivirus in HEK293T cells using third-generation packaging system.

- Screen Execution: Infect model organism cells at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single integrations. Select with puromycin (2 μg/mL, 48-72 hours). Split into experimental arms (e.g., disease stimulus vs. control).

- Phenotypic Selection: Culture cells for 14-21 population doublings under selective pressure. Harvest genomic DNA at multiple time points.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Amplify sgRNA regions with barcoded primers. Sequence on Illumina platform. Analyze sgRNA depletion/enrichment using MAGeCK or BAGEL.

Optimization Steps: Determine optimal infection efficiency and selection conditions in pilot studies. Include biological replicates (minimum n=3). For in vivo applications, consider using barcoded subpools to track different conditions within single animals.

Figure 1: Integrated Functional Genomics Workflow for Disease Mechanism Discovery. Experimental approaches (green) generate data that undergoes computational analysis (blue) to yield mechanistic insights (red).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Genomics in Disease Models

| Category | Specific Reagents/Systems | Key Applications | Considerations for Model Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, KAPA HyperPrep, Nextera DNA Flex | Library preparation for NGS applications | Check compatibility with species-specific sequences; may require optimization for non-model organisms |

| Antibodies | Histone modification panels (H3K4me3, H3K27ac), RNA Pol II, Transcription factor-specific | ChIP-Seq, protein localization, Western validation | Species cross-reactivity must be validated; consider epitope conservation |

| CRISPR Systems | Lentiviral sgRNA libraries, Cas9 variants (nickase, deadCas9), Base editors | Functional screening, targeted gene manipulation | Delivery efficiency varies by model system; optimize for each organism |

| Cell Culture Media | Defined media formulations, serum-free options, differentiation kits | Maintaining primary cells, organoid cultures | Physiological relevance to human systems; species-specific growth factors |

| Bioinformatic Tools | DESeq2, MACS2, Seurat, GATK, Cell Ranger | Data analysis, visualization, and interpretation | Genome annotation quality critical; may require custom pipeline development |

Data Analysis and Integration Frameworks

Statistical Approaches for Gene Prioritization

The transition from gene discovery to mechanism elucidation requires sophisticated statistical frameworks for prioritizing candidate genes from association studies. Recent research comparing genome-wide association studies and rare-variant burden tests reveals that these approaches systematically rank genes differently, with each method highlighting distinct aspects of trait biology [31]. Integrated frameworks that leverage both common and rare variant signals provide more comprehensive insights into disease architecture.

Gene burden analytical frameworks have been specifically developed for Mendelian diseases, such as the geneBurdenRD package used in the 100,000 Genomes Project [32]. These tools assess false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted disease-gene associations through a cohort allelic sums test (CAST) statistic used as covariate in a Firth's logistic regression model. Genes are tested for enrichment in cases versus controls of rare, protein-coding variants that are predicted loss-of-function, highly predicted pathogenic, located in constrained coding regions, or de novo.

For complex diseases, integrative association methods that combine evidence from multiple data types—including expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), chromatin interactions, and protein-protein networks—outperform approaches that rely on single data modalities. These methods typically employ Bayesian frameworks that compute posterior probabilities of gene-disease relationships by integrating evidence across diverse genomic datasets.

Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

Integrating data from multiple molecular layers is essential for understanding how genetic variants influence disease phenotypes through intermediate molecular traits. Several computational approaches have been developed for this purpose:

Matrix Factorization Methods: Techniques like Joint Non-negative Matrix Factorization (jNMF) simultaneously decompose multiple omics data matrices (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) to identify shared latent factors that represent coordinated cross-omic patterns. These factors can be tested for association with disease phenotypes.

Network Propagation Algorithms: These methods diffuse signal from known disease-associated genes through molecular interaction networks to prioritize additional candidate genes. The random walk with restart algorithm is particularly effective for this application, leveraging the "guilt by association" principle.

Concordance Analysis: This approach identifies genes where multiple types of molecular evidence converge—for example, where genetic variants both associate with disease risk and influence expression of the same gene (colocalization). Such convergence provides stronger evidence for mechanistic involvement than any single data type alone.

Table 3: Statistical Frameworks for Gene Prioritization in Disease Research

| Method Type | Representative Tools | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burden Testing | geneBurdenRD, SKAT, STAAR | Powerful for rare variant analysis in Mendelian diseases | Limited applicability to complex traits with polygenic architecture |

| Network Propagation | PRINCE, DOMINO, DIAMOnD | Leverages prior knowledge of molecular interactions | Dependent on network quality and completeness |

| Multi-omics Integration | MOFA, mixOmics, PaintOmics | Captures coordinated variation across molecular layers | Computational intensive; requires large sample sizes |

| Colocalization Methods | COLOC, eCAVIAR, fastENLOC | Determines shared causal variants across traits | Requires well-powered molecular QTL studies |

Figure 2: Gene Prioritization Framework Integrating Genetic and Functional Genomics Data. Multiple data sources (yellow) are integrated to prioritize genes (green) for experimental follow-up, leading to mechanistic understanding (red).

Case Studies: From Gene Discovery to Mechanism

Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Non-Coding Genes

A landmark study investigating neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) illustrates the power of functional genomics to uncover novel disease mechanisms in previously overlooked genomic regions. Researchers identified mutations in RNU2-2, a small non-coding gene, as responsible for a relatively common NDD [33]. This discovery followed their earlier identification of RNU4-2 (ReNU syndrome) as another non-coding RNA gene associated with NDDs, establishing a new class of disease genes.

The study leveraged whole-genome sequencing of more than 50,000 individuals through Genomics England to detect mutations in RNU2-2, a gene previously thought to be inactive [33]. Patients with RNU2-2 syndrome presented with more severe epilepsy compared to those with RNU4-2 syndrome, suggesting distinct although related mechanisms. This discovery was particularly notable because it cemented the biological significance of small non-coding RNA genes in neurodevelopmental disorders, expanding the search space for disease-associated variants beyond protein-coding regions.

The functional genomics approach applied in this study demonstrates how moving beyond conventional gene annotations can reveal new disease biology. The discovery enables affected families to receive specific genetic diagnoses, connect with others in similar situations, and gain better understanding of how to manage the condition. For researchers, it opens new avenues to explore the molecular mechanisms through which non-coding RNAs influence brain development and function.

Hypertension and Differential Expression Analysis

A comprehensive functional genomics study of hypertension illustrates how transcriptomic analyses can reveal novel molecular pathways in common complex diseases. Researchers identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) contributing to hypertension pathophysiology by analyzing 22 publicly available cDNA Affymetrix datasets using an integrated system-level framework [34].

Through robust multi-array analysis and differential studies, the team identified seven key hypertension-related genes: ADM, ANGPTL4, USP8, EDN, NFIL3, MSR1, and CEBPD. Functional enrichment analysis revealed significant roles for HIF-1-α transcription, endothelin signaling, and GPCR-binding ligand pathways. The researchers validated these findings using quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR), confirming approximately three-fold higher expression changes in ADM, ANGPTL4, USP8, and EDN1 genes compared to controls, while CEBPD, MSR1 and NFIL3 were downregulated [34].

This systematic approach to gene expression analysis in hypertension demonstrates how functional genomics can identify not just individual genes but entire functional modules and pathways dysregulated in common diseases. The aberrant expression patterns of these genes are associated with the pathophysiological development of cardiovascular abnormalities, providing new targets for therapeutic intervention and personalized treatment approaches.

The integration of functional genomics approaches has fundamentally transformed our ability to move from gene discovery to understanding common disease mechanisms. By combining high-throughput technologies, advanced computational methods, and model organism studies, researchers can now systematically dissect the complex pathways through which genetic variants influence disease phenotypes. The frameworks and methodologies outlined in this whitepaper provide a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to elucidate disease mechanisms.

Looking forward, several emerging technologies promise to further accelerate this field. Generative genomic models like Evo demonstrate the potential to design novel genetic elements for probing gene function, potentially enabling more efficient exploration of sequence-function relationships [30]. Long-read sequencing technologies continue to improve, offering enhanced ability to detect structural variants and phase alleles across complex genomic regions. Single-cell multi-omics technologies enable unprecedented resolution for mapping cellular heterogeneity in disease tissues.

The increasing availability of large-scale biobanks with paired genetic and deep phenotypic data, such as the 100,000 Genomes Project [32], provides the statistical power necessary to detect subtle genetic effects and their interactions with environmental factors. As these resources grow and methods for integrative analysis improve, we anticipate accelerated discovery of disease mechanisms and new targets for therapeutic intervention across a wide spectrum of common diseases.

For researchers in this field, success will increasingly depend on interdisciplinary collaboration across genetics, computational biology, molecular biology, and clinical medicine. The integration of diverse expertise and methodologies will be essential for translating the promise of functional genomics into meaningful advances in understanding and treating human disease.

High-Throughput Workflows and CRISPR Tools in Action

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis Protocols in Zebrafish

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has fundamentally transformed functional genomics, enabling researchers to move from genomic sequence data to functional understanding with unprecedented speed and precision. In vertebrate models, CRISPR-based tools allow for the systematic perturbation of genes and regulatory regions to analyze ensuing phenotypic changes at a scale that can inform both basic biology and human pathology [2]. The zebrafish (Danio rerio), with its optical clarity, high fecundity, and genetic tractability, has emerged as a premier model for high-throughput functional genomics. The ability to rapidly generate targeted mutations in zebrafish provides an essential tool for large-scale functional annotation of genes, modeling human diseases, and dissecting complex genetic interactions [2] [35]. This technical guide details established and emerging CRISPR-Cas9 protocols that form the backbone of modern zebrafish reverse genetics approaches.

Core Principles of CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is a bacterial adaptive immune system repurposed for programmable genome editing. The core system consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in DNA, and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), which directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus via complementary base pairing [36] [37]. Upon DSB formation, the cell engages endogenous DNA repair mechanisms:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The dominant repair pathway in zebrafish embryos, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function by causing frameshifts [2].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A less frequent but more precise pathway that can be co-opted with an exogenous DNA template to introduce specific sequence changes or insertions [2].

The simplicity, efficiency, and versatility of CRISPR-Cas9 have made it the technology of choice for genome engineering in zebrafish and many other model organisms [38].

Established Mutagenesis Workflows

High-Throughput Targeted Mutagenesis

A complete workflow for high-throughput mutagenesis enables researchers to target tens to hundreds of genes per year efficiently. This pipeline encompasses target selection, cloning-free sgRNA synthesis, embryo microinjection, validation of sgRNA activity, and genotyping of founders and subsequent generations [35]. Table 1 summarizes the key steps and timeline for establishing a stable mutant line.

Table 1: Workflow and Timeline for Generating Zebrafish Mutant Lines

| Phase | Key Steps | Estimated Time | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Target selection; sgRNA design & synthesis; Cas9 mRNA/procurement | 1-2 weeks | Optimized sgRNAs; Injection-ready Cas9 |

| Microinjection | Co-injection of sgRNA and Cas9 into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos | 1 day | Injected embryos (G0) |

| Founder Screening | Raise G0 to adulthood; outcross & screen F1 progeny for germline transmission | ~3 months | Identified founders carrying mutant alleles |

| Line Establishment | Raise & genotype F1 heterozygotes; incross to generate homozygous mutants | ~6 months | Stable, genetically validated mutant line |

This workflow achieves a 99% success rate for generating mutations, with an average germline transmission rate of 28% [2]. The use of chemically synthesized, modified sgRNAs (crRNA:tracrRNA duplexes) increases cutting efficiency and reduces toxicity compared to in vitro-transcribed guides [39] [40].

Advanced Insertional Mutagenesis with CRIMP