Multi-Omics Data Integration: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of multi-omics data integration, a cornerstone of modern precision medicine and systems biology.

Multi-Omics Data Integration: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of multi-omics data integration, a cornerstone of modern precision medicine and systems biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it systematically explores the foundational principles, diverse computational methodologies, and practical applications of integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data. The content spans from core concepts and biological networks to advanced machine learning and graph-based techniques, addressing common analytical pitfalls and performance evaluation. By synthesizing insights from recent literature and tools, this guide aims to empower scientists to effectively leverage multi-omics integration for enhanced disease subtyping, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development.

Demystifying Multi-Omics: Core Concepts, Data Types, and Biological Networks

Defining Multi-Omics Integration and Its Significance in Systems Biology

Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in biological research, moving beyond single-layer analysis to combine data from various molecular levels—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to construct a comprehensive view of biological systems [1] [2]. This approach forms the cornerstone of systems biology, an interdisciplinary field that seeks to understand complex living systems by integrating multiple types of quantitative molecular measurements with sophisticated mathematical models [1]. The fundamental premise is that biological entities exhibit emergent properties that cannot be fully understood by studying individual components in isolation [3].

The significance of multi-omics integration in systems biology lies in its ability to reveal the complex interplay between different molecular layers, thereby bridging the gap from genotype to phenotype [2]. By simultaneously analyzing multiple omics datasets, researchers can uncover novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying health and disease, accelerate biomarker discovery, identify new therapeutic targets, and ultimately advance the development of personalized medicine [2] [3] [4]. As technological advancements continue to reduce costs and increase throughput, multi-omics approaches are becoming increasingly accessible and are poised to revolutionize our understanding of biological complexity [1] [5].

Key Integration Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Various computational strategies have been developed to tackle the challenge of integrating heterogeneous omics data, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration Approaches

| Integration Method | Core Principle | Representative Tools | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Integration | Links omics data via shared biological knowledge (e.g., pathways, ontologies) [3]. | OmicsNet, PaintOmics, STATegra [3] [6] | Hypothesis generation; exploratory analysis of associations between omics layers [3]. |

| Statistical Integration | Uses quantitative measures (correlation, clustering) to combine or compare datasets [3]. | mixOmics, MOFA+ [3] [7] | Identifying co-expression patterns; clustering samples based on multi-omics profiles [2] [3]. |

| Model-Based Integration | Employs mathematical models to simulate system behavior [3]. | PK/PD models, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [3] [8] | Understanding system dynamics and regulation; predicting drug ADME [3] [8]. |

| Network-Based Integration | Maps omics data onto shared biochemical networks and pathways [3] [5]. | OmicsNet, KnowEnG [3] [6] | Gaining mechanistic understanding; visualizing interactions between different molecular types [2] [3]. |

The choice of integration strategy often depends on whether the data is matched (different omics measured from the same cell/sample) or unmatched (omics from different cells/samples) [7]. Matched data allows for vertical integration, using the cell itself as an anchor, while unmatched data requires more complex diagonal integration methods that project cells into a co-embedded space to find commonality [7]. Emerging deep learning approaches, particularly variational autoencoders (VAEs), are increasingly used for their ability to handle high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and missing values across data types [9] [8].

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Knowledge-Driven Multi-Omics Integration

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for knowledge-driven integration of transcriptomics and proteomics data using accessible web-based tools, facilitating the interpretation of complex molecular datasets in a biological context.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Biological Samples (e.g., tissue, blood plasma) | Source material for generating multi-omics data. Must be processed and stored appropriately to preserve biomolecule integrity [1]. |

| ExpressAnalyst | Web-based tool for processing and analyzing transcriptomics and proteomics data, identifying significant features [6]. |

| MetaboAnalyst | Web-based platform for metabolomics or lipidomics data analysis [6]. |

| OmicsNet | Web-based tool for knowledge-driven integration, building and visualizing biological networks in 2D or 3D space [6]. |

| Normalized Data Matrices | Processed and normalized omics data files (e.g., from RNA-Seq, proteomics) for input into analysis tools [6]. |

Procedure

Single-Omics Data Analysis

- Transcriptomics/Proteomics with ExpressAnalyst: Upload your normalized gene expression or protein abundance matrix. Perform quality control, differential expression analysis, and functional enrichment to identify lists of significant genes or proteins [6].

- Metabolomics/Lipidomics with MetaboAnalyst: For complementary metabolomic data, use MetaboAnalyst to perform similar preprocessing, statistical analysis, and identification of significant metabolites or lipids [6].

Knowledge-Driven Integration with OmicsNet

- Input Significant Features: Import the lists of significant molecules (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) identified in Step 1 into OmicsNet.

- Network Construction: Select relevant biological databases (e.g., KEGG, Reactome) to retrieve known interactions between your input molecules and build an integrated network [6].

- Network Visualization and Analysis: Visually explore the integrated network in 2D or 3D. Identify central nodes (hubs), interconnected modules, and pathways that are significantly enriched with your multi-omics data, which can reveal underlying biological mechanisms [6].

Data-Driven Integration (Optional)

- For an unsupervised, complementary approach, use a tool like OmicsAnalyst. Input the normalized multi-omics data matrices and metadata.

- Perform joint dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA, t-SNE) to visualize how samples cluster based on the integrated molecular signatures, which can identify novel subtypes or patterns not apparent in single-omics analysis [6].

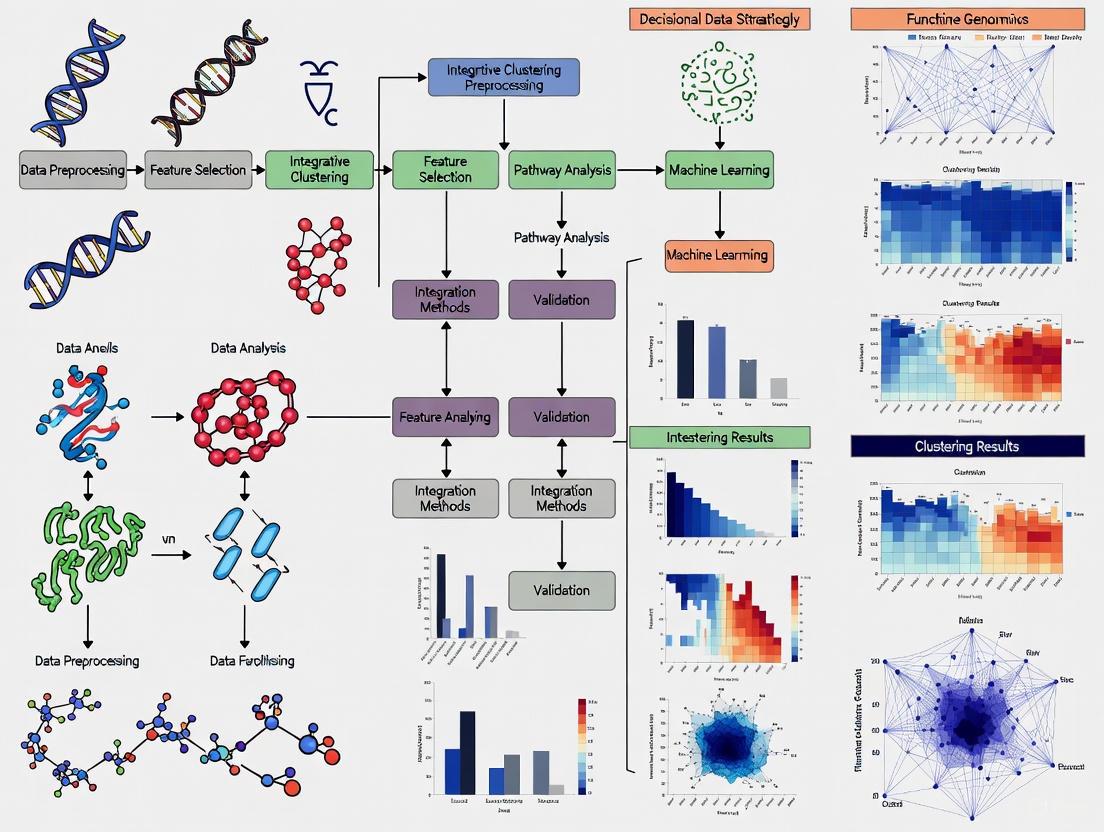

Workflow Visualization

Knowledge-Driven Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

Essential Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Research

The computational landscape for multi-omics integration is diverse, with tools designed for specific data types, integration strategies, and user expertise levels.

Table 3: Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Integration

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Integration Capacity | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| OmicsFootPrint [9] | Deep Learning / Image-based Classification | mRNA, CNV, Protein, miRNA | Transforms multi-omics data into circular images based on genomic location; uses CNNs for classification; high accuracy in cancer subtyping. |

| MOFA+ [7] | Statistical Integration (Factor Analysis) | mRNA, DNA methylation, Chromatin Accessibility | Unsupervised method to disentangle variation across omics layers; identifies principal sources of heterogeneity. |

| Seurat v5 [7] | Unmatched (Diagonal) Integration | mRNA, Chromatin Accessibility, Protein, DNA methylation | "Bridge integration" for mapping across different datasets/technologies; widely used in single-cell genomics. |

| GLUE [7] | Unmatched Integration (Graph VAE) | Chromatin Accessibility, DNA methylation, mRNA | Uses graph-based variational autoencoders and prior biological knowledge to guide integration of unpaired data. |

| Analyst Suite (ExpressAnalyst, MetaboAnalyst, OmicsNet) [6] | Web-based Analysis & Knowledge-Driven Integration | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Lipidomics, Metabolomics | User-friendly web interface; workflow covering single-omics analysis to network-based multi-omics integration. |

For researchers without strong programming backgrounds, web-based platforms like the Analyst Suite (ExpressAnalyst, MetaboAnalyst, OmicsNet) provide an accessible entry point, democratizing complex omics analyses [6]. Conversely, command-line tools and packages like MOFA+ and those built on variational autoencoders offer greater flexibility for computational biologists handling large, complex datasets [8] [7].

Visualization of Multi-Omics Network Relationships

Biological networks provide a powerful framework for interpreting multi-omics data, revealing how molecules from different layers interact functionally.

Multi-Omics Network and Phenotype Linkage

This network view illustrates the core objective of multi-omics integration in systems biology: to move beyond correlative lists of molecules and towards causal, mechanistic models that explain how interactions across genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic layers collectively influence the observable phenotype [2] [3].

The complexity of biological systems necessitates a layered approach to understanding molecular mechanisms. The major omics fields—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—provide complementary insights into these processes, from genetic blueprint to functional phenotype. When integrated, these layers form a powerful multi-omics approach that offers a holistic view of biological systems, enabling researchers to link gene expression to protein activity and metabolic outcomes [10] [11]. This integration is transforming biomedical research, drug discovery, and precision medicine by uncovering intricate molecular interactions not apparent through single-omics approaches [12] [13].

The table below summarizes the core components, analytical focuses, and key technologies for each major omics layer.

Table 1: Overview of the Four Major Omics Layers

| Omics Layer | Core Biomolecule | Analytical Focus | Primary Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics [10] | DNA and Genes | The entirety of an organism's genome and its influence on health and disease. | DNA Sequencing, GWAS, Microarrays |

| Transcriptomics [10] [11] | RNA and Transcripts | The complete set of RNA transcripts in a cell, reflecting active gene expression under specific conditions. | RNA-Seq, Microarrays |

| Proteomics [10] | Proteins and Polypeptides | The entire set of expressed proteins, including their structures, modifications, interactions, and functions. | Mass Spectrometry, 2D-GE, Protein Microarrays |

| Metabolomics [10] [11] | Metabolites | The comprehensive collection of small-molecule metabolites, representing the final product of cellular processes. | Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS, GC-MS), NMR Spectroscopy |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genomics Protocols

Objective: To identify genetic variations and mutations associated with disease states or phenotypic outcomes.

Key Workflow Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from tissue or blood samples.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA and attach adapter sequences for sequencing.

- Sequencing: Perform Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) or Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Data Analysis:

- Alignment: Map sequence reads to a reference genome.

- Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, and deletions (Indels).

- Annotation: Prioritize variants based on genomic location, predicted functional impact, and population frequency.

Transcriptomics Protocols

Objective: To profile global gene expression patterns and identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

Key Workflow Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Extract total RNA, ensuring high RNA Integrity Number (RIN).

- Library Preparation: Enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA), reverse transcribe RNA to cDNA, and attach sequencing adapters.

- Sequencing: Perform RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) on a high-throughput platform.

- Data Analysis:

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome or transcriptome.

- Quantification: Calculate read counts for each gene or transcript.

- Differential Expression: Use statistical models (e.g., in R/Bioconductor packages like DESeq2) to identify DEGs between experimental conditions.

Proteomics Protocols

Objective: To identify and quantify the proteome, including post-translational modifications (PTMs).

Key Workflow Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Lyse cells or tissues and digest proteins into peptides using an enzyme like trypsin.

- Fractionation: Reduce sample complexity via liquid chromatography (LC).

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Ionization: Introduce peptides into the mass spectrometer via electrospray ionization (ESI).

- Mass Analysis: Measure the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of peptides (MS1).

- Fragmentation: Select specific peptides for fragmentation (tandem MS/MS) to generate sequence information.

- Data Analysis: Search MS/MS spectra against protein sequence databases for identification and use MS1 intensity for label-free or isobaric tag-based quantification.

Metabolomics Protocols

Objective: To comprehensively profile small-molecule metabolites to capture a metabolic snapshot.

Key Workflow Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Quench metabolic activity and extract metabolites using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol/acetonitrile/water).

- Data Acquisition:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Ideal for a broad range of semi-polar and polar metabolites.

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Excellent for volatile compounds or those made volatile by derivatization.

- Data Processing: Perform peak picking, alignment, and annotation against metabolite databases (e.g., HMDB, METLIN).

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow and Data Interpretation

Integrating data from the omics layers requires a systematic workflow. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from experimental design to biological insight.

Data Integration and Analysis Strategies

Correlation Analysis: Identify key regulatory nodes by correlating differentially expressed genes (transcriptomics) with differentially abundant proteins (proteomics) and metabolites (metabolomics) [11].

Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Use tools like MetaboAnalyst and Gene Ontology (GO) to find over-represented biological pathways across omics datasets. Converged pathways, where multiple molecular layers show significant changes, are likely to be critically involved in the biological response [11].

Network Construction: Build molecular interaction networks (e.g., gene-regulatory, protein-protein interaction) to visualize complex relationships and identify central hubs that may serve as key regulators or therapeutic targets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| TriZol / Qiazol Reagent | Simultaneous extraction of high-quality RNA, DNA, and proteins from a single sample, reducing sample-to-sample variation. |

| Trypsin (Sequencing Grade) | Proteomics-grade enzyme for specific and efficient digestion of proteins into peptides for mass spectrometry analysis. |

| Isobaric Tags (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) | Enable multiplexed quantification of proteins from multiple samples in a single MS run, improving throughput and accuracy. |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA) | Chemical modification of metabolites for volatility and thermal stability in GC-MS-based metabolomics. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for absolute quantification in proteomics and metabolomics, correcting for instrument variability. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Kits | Clean-up and fractionation of complex metabolite or peptide samples to reduce matrix effects and enhance detection. |

Application in Experimental Research: A Case Study on Disease Mechanisms

The following diagram visualizes a simplified multi-omics investigation into a disease mechanism, such as hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury, as cited in the search results [11].

Experimental Workflow from the Case Study:

- Perturbation: Create a hepatocyte-specific gene knockout (e.g., Gp78) mouse model.

- Profiling: Subject liver tissues from knockout and wild-type mice to transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analysis.

- Integration: Correlate the data to identify a converged pathway. The study found upregulation of lipid metabolism genes (transcriptomics), increased ACSL4 protein (proteomics), and accumulation of oxidized lipids (metabolomics) [11].

- Validation: The integrated data pointed to the ferroptosis cell death pathway. This hypothesis was validated by chemically inhibiting ferroptosis, which abrogated the observed liver injury [11].

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provides a powerful, multi-dimensional framework for deciphering complex biological systems. By moving beyond single-layer analysis, researchers can construct a more complete picture of disease mechanisms, identify robust biomarkers, and discover novel therapeutic targets, thereby advancing the field of precision medicine [12] [13].

Biological networks provide the fundamental framework for a systems-level understanding of life's processes, serving as critical integrators of multi-omics data. These networks—including protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, gene regulatory networks (GRNs), and metabolic pathways—transform disparate molecular data into interconnected, functional maps that elucidate physiological and diseased states [14]. The analysis of these networks has revolutionized our approach to complex diseases by shifting the focus from individual molecules to entire interactive systems, revealing that the structure and dynamics of these networks are frequently disrupted in conditions such as cancer and autoimmune disorders [14]. Within multi-omics research, networks provide the essential scaffolding onto which genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data can be mapped, enabling researchers to uncover emergent properties that cannot be deduced from studying individual components in isolation. This integrated perspective is vital for advancing precision medicine, as it facilitates the identification of diagnostic biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and pathogenic mechanisms that operate at the system level rather than through isolated molecular events.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

Structure and Function of PPI Networks

Protein-protein interaction networks represent the physical and functional associations between proteins within a cell, forming a complex infrastructure that governs cellular machinery. These networks exhibit scale-free topologies, meaning most proteins participate in few interactions, while a small subset of highly connected hub proteins engage in numerous interactions [14]. This organization follows a power-law distribution, which confers both robustness against random failures and vulnerability to targeted attacks on hubs [14]. The structure of PPI networks is characterized by several key topological properties that influence their functional behavior and stability, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Topological Features of Protein-Protein Interaction Networks

| Topological Feature | Definition | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Degree (k) | Number of connections a node (protein) has | Proteins with high degree (hubs) often perform essential cellular functions |

| Average Path Length (L) | Average number of steps along shortest paths for all possible node pairs | Efficiency of information/signal propagation through the network |

| Clustering Coefficient (C) | Measure of how connected a node's neighbors are to each other | Tendency of proteins to form functional modules or complexes |

| Betweenness Centrality | Number of shortest paths that pass through a node | Identification of bottleneck proteins critical for network connectivity |

| Modules | Groups of nodes with high internal connectivity | Functional units or protein complexes performing specialized tasks |

PPI networks are dynamic structures that change across cellular states and conditions. Integration of gene expression data with static PPI maps has revealed a "just-in-time" assembly model where protein complexes are dynamically activated through the stage-specific expression of key elements [14]. This dynamic modular structure has been observed in both yeast and human protein interaction networks, suggesting a conserved organizational principle across species [14].

Experimental Protocols for PPI Mapping

Protocol 2.2.1: Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening for Binary Interactions

Principle: The Y2H system detects binary protein interactions through reconstitution of a transcription factor. The bait protein is fused to a DNA-binding domain, while the prey protein is fused to a transcription activation domain. Interaction between bait and prey reconstitutes the transcription factor, activating reporter gene expression [14].

Workflow:

- Clone Genes of Interest: Insert bait gene into pGBKT7 (DNA-binding domain vector) and prey gene into pGADT7 (activation domain vector).

- Co-transform Yeast: Co-transform bait and prey plasmids into appropriate yeast strain (e.g., AH109 or Y2HGold).

- Select for Interactions: Plate transformed yeast on selective media lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine (-LWH) with optional X-α-Gal for colorimetric detection.

- Validate Interactions: Confirm positive interactions through β-galactosidase assay (qualitative filter lift or quantitative liquid assay).

- Control Experiments: Perform parallel transformations with empty vectors and known non-interacting protein pairs to eliminate false positives.

Critical Considerations:

- Test bait autoactivation by plating on -LWHA (adenine-deficient) media before library screening

- Use multiple reporters (HIS3, ADE2, MEL1, lacZ) to reduce false positives

- Consider membrane protein systems (e.g., split-ubiquitin) for membrane-bound proteins

Protocol 2.2.2: Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) for Complex Identification

Principle: AP-MS identifies protein complexes through immunoaffinity purification of tagged bait proteins followed by mass spectrometric identification of co-purifying proteins [14].

Workflow:

- Cell Line Generation: Create stable cell lines expressing tagged (e.g., FLAG, HA, TAP) bait protein and control tag-only constructs.

- Cell Lysis and Clarification: Lyse cells under non-denaturing conditions (e.g., 0.5% NP-40, 150mM NaCl) with protease/phosphatase inhibitors.

- Affinity Purification: Incubate lysates with affinity resin (e.g., anti-FLAG M2 agarose, streptavidin beads) for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Stringent Washes: Wash beads 3-5 times with lysis buffer to remove non-specific interactions.

- Elution and Digestion: Elute complexes with competitive peptide (3xFLAG peptide) or on-bead trypsin digestion.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS and identify specific interactors using statistical frameworks (SAINT, CompPASS).

AP-MS Workflow for PPI Identification

Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Network Analysis

| Reagent/Method | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | Detection of binary protein interactions | High-throughput capability, in vivo context |

| Co-immunoprecipitation | Validation of protein complexes from native sources | Physiological relevance, requires specific antibodies |

| Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) | Visualization of protein interactions in living cells | Spatial context, real-time monitoring |

| Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) | Detection of endogenous protein interactions in fixed cells | Single-molecule sensitivity, in situ validation |

| Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) Tags | Purification of protein complexes under native conditions | Reduced contamination, two-step purification |

| Cross-linkers (DSS, BS3) | Stabilization of transient interactions for MS analysis | Captures weak/transient interactions |

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs)

Architecture and Properties of GRNs

Gene regulatory networks represent the directional relationships between transcription factors, regulatory elements, and their target genes that collectively control transcriptional programs. Recent single-cell multi-omic technologies have revolutionized GRN inference by enabling the mapping of regulatory relationships at unprecedented resolution [15]. GRNs exhibit distinct structural properties that define their functional characteristics, including hierarchical organization, modularity, and sparsity [16]. Analysis of large-scale perturbation data has revealed that only approximately 41% of gene perturbations produce measurable effects on transcriptional networks, highlighting the robustness and redundancy built into regulatory systems [16].

GRNs display asymmetric distributions of in-degree (number of regulators controlling a gene) and out-degree (number of genes regulated by a transcription factor), with out-degree distributions typically being more heavy-tailed due to the presence of master regulators that control numerous targets [16]. Furthermore, GRNs contain extensive feedback loops, with approximately 2.4% of regulatory pairs exhibiting bidirectional effects, creating complex dynamical behaviors that are essential for cellular decision-making processes [16].

Computational Protocols for GRN Inference

Protocol 3.2.1: SCENIC+ Workflow for Single-Cell Multi-omic GRN Inference

Principle: SCENIC+ integrates scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data to infer transcription factor activity and reconstruct regulatory networks by linking cis-regulatory elements to target genes [15].

Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Perform quality control, normalization, and batch correction on both scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets.

- Region-to-Gene Linking: Identify potential regulatory relationships by correlating chromatin accessibility at cis-regulatory elements with gene expression across cells.

- Transcription Factor Motif Analysis: Scan accessible regions for TF binding motifs using position weight matrices (e.g., from JASPAR, CIS-BP).

- TF Activity Inference: Calculate TF activity scores using AUCell or regression-based methods that consider both TF expression and motif accessibility.

- Network Construction: Build the GRN by connecting TFs to target genes through regulatory elements with significant associations.

- Network Refinement: Prune indirect interactions using context-specific perturbation data or statistical methods.

Critical Parameters:

- Distance threshold for enhancer-gene linking (typically 50kb-1Mb from TSS)

- Minimum correlation coefficient for region-to-gene links (r > 0.3)

- Motif similarity threshold (80-95% similarity to reference motif)

Protocol 3.2.2: Dynamical Systems Modeling for GRN Inference from Perturbation Data

Principle: This approach models gene expression dynamics using differential equations to capture the temporal evolution of regulatory relationships following perturbations [15] [16].

Workflow:

- Time-Series Data Collection: Perform scRNA-seq at multiple time points following genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR knockout).

- Network Structure Initialization: Generate initial network hypothesis using correlation-based methods or prior knowledge.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit ordinary differential equation parameters to time-series expression data:

dXᵢ/dt = βᵢ + Σⱼ WᵢⱼXⱼ - γᵢXᵢWhere Xᵢ is expression of gene i, βᵢ is basal transcription, Wᵢⱼ is regulatory weight, and γᵢ is degradation rate. - Model Selection: Use information criteria (AIC/BIC) or cross-validation to select optimal network structure.

- Validation: Test predicted regulatory relationships using orthogonal methods (e.g., ChIP-seq, additional perturbations).

GRN Inference from Multi-omic Data

Methodological Foundations for GRN Inference

Table 3: Computational Methods for GRN Inference from Single-Cell Multi-omic Data

| Methodological Approach | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Measures association between TF and target gene expression | Simple implementation, fast computation | Cannot distinguish direct vs. indirect regulation |

| Regression Models | Models gene expression as function of potential regulators | Quantifies effect sizes, handles multiple regulators | Prone to overfitting with many predictors |

| Probabilistic Models | Represents regulatory relationships as probability distributions | Incorporates uncertainty, handles noise | Often assumes specific gene expression distributions |

| Dynamical Systems | Uses differential equations to model expression changes over time | Captures temporal dynamics, models feedback | Requires time-series data, computationally intensive |

| Deep Learning | Neural networks learn complex regulatory patterns from data | Captures non-linear relationships, high accuracy | Requires large datasets, limited interpretability |

Metabolic Networks

Representation and Analysis of Metabolic Networks

Metabolic networks represent the complete set of metabolic and physical processes that determine the physiological and biochemical properties of a cell. These networks can be represented in multiple ways, each offering different insights into metabolic organization and function [17]. The substrate-product network represents metabolites as nodes and biochemical reactions as edges, focusing on the flow of chemical compounds through metabolic pathways [17]. Alternatively, reaction networks represent enzymes or reactions as nodes, highlighting the functional relationships between catalytic activities [17].

A critical consideration in metabolic network analysis is the treatment of ubiquitous metabolites (e.g., ATP, NADH, H₂O), which participate in numerous reactions and can create artificial connections that obscure meaningful metabolic pathways [17]. Advanced network representations address this challenge by considering atomic traces—tracking specific atoms through reactions—to establish biochemically meaningful connections that reflect actual metabolic transformations rather than mere participation in the same reaction [17].

Protocol for Metabolic Network Reconstruction and Analysis

Protocol 4.2.1: Genome-Scale Metabolic Network Reconstruction

Principle: This protocol creates organism-specific metabolic networks by integrating genomic, biochemical, and physiological data to generate comprehensive metabolic models [17].

Workflow:

- Draft Network Generation: Automatically generate initial network from genome annotation using tools like ModelSEED or RAVEN.

- Gap Filling and Curation: Manually curate the network by filling metabolic gaps based on physiological data and literature evidence.

- Stoichiometric Matrix Construction: Build an S-matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions.

- Compartmentalization: Assign reactions to appropriate cellular compartments (e.g., cytosol, mitochondria).

- Biomass Reaction Definition: Formulate biomass reaction representing cellular composition based on experimental data.

- Constraint-Based Analysis: Implement flux balance analysis (FBA) to predict metabolic capabilities under different conditions.

Implementation Details:

- Use databases such as KEGG [18] and MetaCyc for reaction and pathway information

- Apply thermodynamic constraints (energy balance) to improve prediction accuracy

- Integrate transcriptomic data to create context-specific models (GIMME, iMAT)

Protocol 4.2.2: Constraint-Based Flux Analysis of Metabolic Networks

Principle: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predicts metabolic flux distributions by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass production) subject to stoichiometric and capacity constraints [17].

Workflow:

- Stoichiometric Constraints: Define the mass balance constraints for each metabolite: S·v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector.

- Capacity Constraints: Set lower and upper bounds for reaction fluxes based on enzyme capacity and thermodynamic feasibility.

- Objective Function: Define biological objective such as biomass maximization, ATP production, or metabolite synthesis.

- Linear Programming Solution: Solve the optimization problem: maximize Z = cᵀv subject to S·v = 0 and vₗ ≤ v ≤ vᵤ.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform robustness analysis by varying environmental conditions or gene knockouts.

- Validation: Compare predictions with experimental flux measurements (e.g., ¹³C flux analysis).

Metabolic Network Reconstruction Workflow

Table 4: Key Databases and Tools for Metabolic Network Research

| Resource | Type | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG PATHWAY [18] | Database | Metabolic pathway visualization and analysis | Manually drawn pathway maps, organism-specific pathways |

| MetaCyc | Database | Non-redundant reference metabolic pathways | Curated experimental data, enzyme information |

| BiGG Models | Database | Genome-scale metabolic models | Standardized models, biochemical data |

| ModelSEED | Tool | Automated metabolic reconstruction | Rapid model generation, gap filling |

| CobraPy | Tool | Constraint-based modeling | FBA, flux variability analysis |

| MINEs | Database | Prediction of novel metabolic reactions | Expanded metabolic space, hypothetical enzymes |

Multi-Omics Integration Through Biological Networks

Network-Based Data Integration Strategies

Biological networks provide the ideal framework for multi-omics data integration, enabling researchers to map diverse molecular measurements onto functional relationships and pathways. The STRING database exemplifies this approach by compiling protein-protein association data from multiple sources—including experimental results, computational predictions, and curated knowledge—to create comprehensive networks that span physical and functional interactions [19]. The latest version of STRING introduces regulatory networks with directionality information, further enhancing its utility for multi-omics integration [19].

Deep generative models, particularly variational autoencoders (VAEs), have emerged as powerful tools for multi-omics integration, addressing challenges such as high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and missing values across data types [8]. These models can learn latent representations that capture the joint structure of multiple omics layers, enabling data imputation, augmentation, and batch effect correction while facilitating the identification of complex biological patterns relevant to disease mechanisms [8].

Protocol for Multi-Omic Network Integration

Protocol 5.2.1: Multi-Layer Network Analysis for Disease Mechanism Identification

Principle: This approach integrates PPI, GRN, and metabolic networks to create multi-layer networks that capture different aspects of cellular organization, enabling identification of key regulatory points across multiple biological scales.

Workflow:

- Layer-Specific Network Construction: Generate high-quality PPI, GRN, and metabolic networks for the system of interest.

- Node Mapping Across Layers: Establish correspondence between entities across different network types (e.g., transcription factors in GRN that are also proteins in PPI network).

- Cross-Layer Edge Definition: Identify biologically meaningful connections between layers (e.g., transcription factors regulating metabolic enzymes).

- Multi-Layer Community Detection: Identify modules that span multiple network layers using methods like multi-layer Louvain clustering.

- Key Node Identification: Calculate multi-layer centrality measures to identify nodes with important roles across multiple biological processes.

- Functional Enrichment: Perform pathway enrichment analysis on cross-layer modules to interpret their biological significance.

Applications:

- Identification of master regulators that control coordinated changes across multiple cellular functions

- Discovery of network-based biomarkers that span genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolic levels

- Prediction of system-wide effects of therapeutic interventions

Network Pharmacology and Drug Development

Biological networks have transformed drug development by enabling network pharmacology approaches that target disease modules rather than individual proteins. The STRING database supports these applications by providing comprehensive protein networks with directionality information that can illuminate regulatory mechanisms in disease states [19]. Similarly, the KEGG PATHWAY database offers manually drawn pathway maps that represent molecular interaction and reaction networks essential for understanding drug mechanisms and identifying potential side effects [18].

Network-based drug discovery approaches include:

- Network proximity analysis to identify drugs that target disease-associated network neighborhoods

- Disease module identification to pinpoint coherent functional units disrupted in pathology

- Multi-omics signature mapping to connect drug-induced changes across molecular layers

These approaches are particularly valuable for understanding complex diseases where multiple genetic and environmental factors interact through complex network relationships that cannot be adequately addressed by single-target therapies [14].

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has catalyzed the generation of massive multi-omics datasets, fundamentally advancing our understanding of cancer biology [20]. Large-scale public data repositories serve as indispensable resources for researchers investigating tumor heterogeneity, molecular classification, and therapeutic vulnerabilities [21]. These repositories provide comprehensive molecular characterizations across diverse cancer types, enabling systematic exploration of shared and unique oncogenic drivers [20]. The integration of different omics types creates heterogeneous datasets that present both opportunities and analytical challenges due to variations in measurement units, sample numbers, and features [21]. This application note provides a detailed overview of four cornerstone repositories - TCGA, CPTAC, ICGC, and CCLE - with structured comparisons, experimental protocols, and practical guidance for their research application within multi-omics integration frameworks.

Repository Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Cancer Data Repositories

| Repository | Primary Focus | Sample Types | Key Omics Data Types | Scale | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | Molecular characterization of primary tumors | Primary tumor samples, matched normal | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic [22] | 33 cancer types, ~11,000 patients [23] | Pan-cancer atlas; standardized processing; multi-institutional consortium |

| CPTAC (Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium) | Proteogenomic integration | Tumor tissues, biofluids | Proteomic, phosphoproteomic, genomic, transcriptomic | 10+ cancer types [21] | Deep proteomic profiling; post-translational modifications; proteogenomic integration |

| ICGC (International Cancer Genome Consortium) | Genomic analysis with clinical annotation | Tumor-normal pairs | Genomic, transcriptomic, clinical data [24] | 100,000 patients, 22 tumor types, 13 countries [24] | International collaboration; detailed clinical annotation; treatment outcomes |

| CCLE (Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia) | Preclinical model characterization | Cancer cell lines | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, dependency data [25] | 1,000+ cell lines [23] | Functional screening data; drug response; gene dependency maps |

Data Content and Technical Specifications

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Data Availability

| Repository | Genomics | Transcriptomics | Proteomics | Epigenomics | Clinical Data | Specialized Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | WGS, WES, SNP arrays | RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq | RPPA, mass spectrometry | DNA methylation arrays | Detailed clinical annotations | Pathological images |

| CPTAC | WGS, WES | RNA-Seq | Global proteomics, phosphoproteomics | DNA methylation | Clinical outcomes | Post-translational modifications |

| ICGC | WGS, WES | RNA-Seq | Limited | DNA methylation | Comprehensive clinical, treatment, lifestyle [24] | Family history, environmental exposures [24] |

| CCLE | WES, SNP arrays | RNA-Seq | Reverse-phase protein arrays | DNA methylation | Cell line metadata | CRISPR screens, drug sensitivity [25] |

Repository-Specific Application Protocols

TCGA: Molecular Subtyping and Classification

Protocol: Cancer Subtype Classification Using TCGA Data

Purpose: To classify tumor samples into molecular subtypes using pre-trained classifier models based on TCGA data.

Background: TCGA has defined molecular subtypes for major cancer types based on integrated multi-omics analysis. Recently, a resource of 737 ready-to-use models has been developed to bridge TCGA's data library with clinical implementation [22].

Materials:

- TCGA dataset or novel tumor dataset for classification

- Computational resources (R/Python environment)

- GitHub repository: https://github.com/NCICCGPO/gdan-tmp-models [22]

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize gene expression data using TPM (Transcripts Per Million) with log2 transformation (pseudo-count +1) [25]

- Process DNA methylation data using beta values with quality control filtering

- For miRNA data, implement cross-platform normalization if combining datasets

Model Selection:

- Identify appropriate classifier from the repository based on cancer type

- Select data type (gene expression, DNA methylation, miRNA, copy number, mutation calls, or multi-omics)

- Choose from five training algorithms available in the resource

Subtype Assignment:

- Apply the selected model to processed omics data

- Generate classification probabilities for each subtype

- Assign final subtype based on highest probability score

Validation:

- Compare subtype distribution with known clinical features

- Assess survival differences between subtypes using Kaplan-Meier analysis

- Validate biological coherence through pathway enrichment analysis

Troubleshooting:

- For low classification confidence, consider ensemble approaches combining multiple models

- Address batch effects using ComBat or similar methods when integrating multiple datasets

- Verify tumor purity estimates, as this can significantly impact classification accuracy [23]

ICGC ARGO: Clinical Data Integration and Analysis

Protocol: Integrating Genomic and Clinical Data Using ICGC ARGO Framework

Purpose: To harmonize and analyze clinically annotated genomic data using the ICGC ARGO data dictionary and platform.

Background: The ICGC ARGO Data Dictionary provides a standardized framework for collecting clinical data across multiple institutions and countries, enabling robust correlation of genomic findings with clinical outcomes [24].

Materials:

- ICGC ARGO Data Dictionary (https://docs.icgc-argo.org/dictionary) [24]

- ARGO Data Platform access (https://platform.icgc-argo.org/) [26]

- DACO approval for controlled data access [27]

Procedure:

- Data Dictionary Familiarization:

- Access the interactive dictionary viewer at https://docs.icgc-argo.org/dictionary

- Review the entity-relationship model comprising fifteen entities

- Identify core (mandatory) versus extended (optional) fields

- Understand conditional attribute requirements

Data Access and Filtering:

- Navigate the ARGO Data Platform File Repository

- Apply clinical and molecular filters using the Data Discovery tool

- Download selected datasets using authorized client tools

Clinical Data Harmonization:

- Map institutional clinical data to ARGO Data Dictionary specifications

- Implement standardized terminology (NCI Thesaurus, LOINC, UMLS) [24]

- Structure data according to the event-based data model capturing clinical timelines

Integrated Analysis:

- Correlate somatic variants with treatment response data

- Analyze progression-free survival based on molecular subtypes

- Investigate environmental and lifestyle factors in cancer progression [24]

Troubleshooting:

- For missing clinical data, utilize multiple imputation methods with appropriate diagnostics

- When encountering terminology inconsistencies, consult the NCIt thesaurus for mapping guidance

- For longitudinal analysis challenges, leverage the event-based model to reconstruct patient journeys

CCLE: Dependency Map Analysis for Target Discovery

Protocol: Identifying Cancer Dependencies Using CCLE and DepMap Integration

Purpose: To identify and validate cancer-specific dependencies and synthetic lethal interactions using CCLE multi-omics data and CRISPR screening data.

Background: The Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) provides genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens across hundreds of cancer cell lines, enabling systematic discovery of tumor vulnerabilities [25] [23].

Materials:

- CCLE multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) [25]

- DepMap gene dependency data (CERES scores) [23]

- Dependency Marker Association (DMA) analytical pipeline [25]

Procedure:

- Data Integration:

- Download gene dependency data from Broad DepMap Public portal

- Acquire somatic mutation data as binary mutation matrix

- Obtain gene expression data (TPM values, log2 transformed)

- Integrate copy number, methylation, proteomics, and metabolomics data [25]

Dependency Marker Association Analysis:

- Perform linear regression modeling with intrinsic subtype covariates

- Analyze dependencies associated with gain-of-function alterations (addiction)

- Identify dependencies associated with loss-of-function alterations (synthetic lethality)

- Focus on metabolic genes and known cancer-associated genes [25]

Cell Line Stratification:

- Apply non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to dependency profiles

- Select optimal cluster number using cophenetic correlation and consensus silhouette scores

- Extract cluster-specific dependency signatures

Biological Validation:

- Construct co-dependency networks using correlation analysis

- Perform Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of cluster signatures

- Calculate single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) scores for pathway activity

Troubleshooting:

- For heterogeneous dependency patterns, apply cluster-specific DMA analysis

- When interpreting synthetic lethality, distinguish between paralog, single pathway, and alternative pathway synthetic lethality [25]

- For translational application, integrate with TCGA data using elastic-net predictive models [23]

Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

Unified Analytical Framework

Protocol: Multi-Omics Study Design and Integration for Cancer Subtyping

Purpose: To provide guidelines for robust multi-omics integration in cancer research, addressing key computational and biological factors.

Background: Multi-omics integration creates heterogeneous datasets presenting challenges in analysis due to variations in measurement units, sample numbers, and features. Evidence-based recommendations can optimize analytical approaches and enhance reliability of results [21].

Materials:

- Multi-omics data from TCGA, ICGC, or CPTAC

- Computational resources for high-dimensional data analysis

- MOI tools (MOGSA, ActivePathways, multiGSEA, iPanda) [21]

Procedure:

- Study Design Considerations:

- Ensure minimum of 26 samples per class for robust clustering

- Select less than 10% of omics features to reduce dimensionality

- Maintain sample balance under 3:1 ratio between classes

- Control noise level below 30% of features [21]

Data Preprocessing:

- Implement platform-specific normalization for each omics type

- Address missing data using appropriate imputation methods

- Perform batch effect correction using ComBat or similar approaches

Feature Selection:

- Apply variance-based filtering to remove uninformative features

- Utilize biological knowledge to prioritize cancer-relevant features

- Employ statistical methods (linear regression, ANOVA) to identify class-discriminatory features

Integration and Analysis:

- Select appropriate integration method based on study objective

- Validate clusters using clinical annotations and survival differences

- Perform biological interpretation through pathway enrichment analysis

Troubleshooting:

- For poor clustering performance, increase sample size and reduce feature selection percentage

- When integrating conflicting signals from different omics layers, utilize methods that weight evidence across data types

- For small sample sizes, employ cross-validation and resampling methods to ensure robustness

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Resource/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Access | ICGC ARGO Data Dictionary | Standardized clinical data collection | Harmonizing clinical data across institutions [24] |

| Data Access | TCGA Classifier Models | Tumor subtype classification | Assigning molecular subtypes to new samples [22] |

| Analytical Tools | Dependency Map (DepMap) | Gene essentiality scores | Identifying tumor vulnerabilities [23] |

| Analytical Tools | DMA Analysis Pipeline | Dependency-marker association | Linking multi-omics features to gene dependencies [25] |

| Analytical Tools | Elastic-net Regression | Predictive modeling | Translating cell line dependencies to patient tumors [23] |

| Analytical Tools | Non-negative Matrix Factorization | Clustering of dependency profiles | Identifying latent patterns in functional screens [25] |

| Analytical Tools | Contrastive PCA | Dataset alignment | Removing batch effects between cell lines and tumors [23] |

| Standards | MOSD Guidelines | Multi-omics study design | Optimizing experimental design and analysis [21] |

The comprehensive ecosystem of public cancer data repositories, including TCGA, CPTAC, ICGC, and CCLE, provides unprecedented resources for advancing cancer research through multi-omics integration. TCGA offers extensive molecular characterization of primary tumors, while CPTAC adds deep proteomic dimensions. ICGC contributes globally sourced, clinically rich datasets, and CCLE enables functional validation in model systems. The successful utilization of these resources requires careful attention to study design, appropriate application of analytical protocols, and adherence to standardized frameworks for data processing and integration. By leveraging the structured protocols, visualization tools, and reagent resources outlined in this application note, researchers can maximize the translational potential of these cornerstone cancer genomics resources, ultimately accelerating the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

The relationship between genotype and phenotype represents one of the most fundamental paradigms in biological research. Traditionally, biological studies have approached this relationship through single-omics lenses, examining individual molecular layers in isolation. However, the advent of high-throughput technologies has enabled the generation of massive, complex multi-omics datasets, necessitating integrative approaches that can capture the full complexity of biological systems [28] [29].

Multi-omics data integration represents a paradigm shift from reductionist to holistic biological investigation. By simultaneously analyzing data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, researchers can now construct comprehensive models that bridge the gap between genetic blueprint and observable traits [29]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in precision medicine, where it facilitates the identification of robust biomarkers and the unraveling of complex disease mechanisms that remain opaque when examining individual omics layers [8] [29].

The technical landscape for multi-omics integration has evolved rapidly, with methods now spanning classical statistical approaches, multivariate methods, and advanced machine learning techniques [29]. The implementation of these approaches has been accelerated by the development of specialized software tools that make integrative analyses accessible to researchers without advanced computational expertise [30]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for implementing these powerful integration strategies to advance biomedical research.

Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

Conceptual Framework and Classification

Multi-omics integration strategies can be conceptually categorized into three primary frameworks: statistical and correlation-based methods, multivariate approaches, and machine learning/artificial intelligence techniques [29]. Each framework offers distinct advantages and is suited to addressing specific biological questions.

Statistical and correlation-based methods form the foundation of multi-omics integration, employing measures such as Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficients to quantify relationships between omics layers. These approaches are particularly valuable for initial exploratory analysis and for identifying direct pairwise relationships between molecular features across different biological scales [29].

Multivariate methods including Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Multiple Co-Inertia Analysis, and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression enable the simultaneous projection of multiple omics datasets into shared latent spaces. These techniques are effective for dimensionality reduction and for identifying coordinated patterns of variation across different molecular layers [30] [29].

Machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques, especially deep generative models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), represent the cutting edge of multi-omics integration. These approaches excel at capturing non-linear relationships and handling the high-dimensionality and heterogeneity characteristic of multi-omics data [8] [29].

Table 1: Classification of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Primary Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical/Correlation-based | Pearson/Spearman correlation, WGCNA, xMWAS | Initial exploratory analysis, Network construction | Simple implementation, Easy interpretation |

| Multivariate Methods | PCA, PLS, Multiple Co-Inertia Analysis | Dimensionality reduction, Pattern identification | Simultaneous multi-omics projection, Latent variable identification |

| Machine Learning/AI | VAEs, Deep Neural Networks, Ensemble Methods | Complex pattern recognition, Predictive modeling | Handles non-linear relationships, Accommodates data heterogeneity |

Network-Based Integration Methods

Network-based approaches have emerged as particularly powerful tools for multi-omics integration, as they naturally represent the complex interdependencies within and between biological layers. Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies modules of highly correlated genes or proteins that can be linked to phenotypic traits [30] [29]. The extension of this approach to multiple omics layers—multi-WGCNA—enables the detection of robust associations across omics datasets while maintaining statistical power through dimensionality reduction [30].

The xMWAS platform implements another network-based approach that performs pairwise association analysis between omics datasets using a combination of PLS components and regression coefficients [29]. This method constructs integrative network graphs where connections represent statistically significant associations between features across different omics layers. Community detection algorithms, such as the multilevel community detection method, can then identify densely connected groups of features that often represent functional biological units [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Network Analysis Using WGCNA

Objective: To identify coordinated patterns across transcriptomics and proteomics datasets and link them to phenotypic traits using weighted correlation network analysis.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for WGCNA Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Column-based with DNase treatment | High-quality RNA isolation for transcriptomics |

| Protein Lysis Buffer | RIPA with protease inhibitors | Protein extraction for proteomic analysis |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | RNA sequencing for transcriptome profiling |

| Mass Spectrometer | Q-Exactive HF-X | High-resolution LC-MS/MS for proteome analysis |

| WGCNA R Package | Version 1.72-1 | Network construction and module identification |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

- Extract RNA and protein from matched samples (n ≥ 12 recommended for statistical power)

- Process RNA samples for transcriptome sequencing using standard Illumina protocols

- Prepare protein samples for LC-MS/MS analysis using tryptic digestion and TMT labeling

- Generate count matrices for transcriptomics and normalized intensity values for proteomics

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Filter transcripts and proteins with >50% missing values across samples

- Normalize transcriptomics data using TPM (Transcripts Per Million) normalization

- Normalize proteomics data using quantile normalization

- Perform batch effect correction using ComBat if required

Network Construction

- Install and load WGCNA package in R environment

- Choose soft-thresholding power based on scale-free topology criterion (R² > 0.8)

- Construct adjacency matrices for each omics dataset separately

- Convert adjacency matrices to topological overlap matrices (TOM)

- Identify modules of highly correlated features using hierarchical clustering with Dynamic Tree Cut

Module-Trait Association

- Calculate module eigengenes (first principal component of each module)

- Correlate module eigengenes with phenotypic traits of interest

- Identify significant module-trait relationships (p-value < 0.05, |correlation| > 0.5)

Cross-Omics Integration

- Correlate eigengenes from transcriptomics and proteomics modules

- Identify preserved modules across omics layers using module preservation statistics

- Extract features from significant cross-omics modules for functional analysis

Protocol 2: Genotype to Phenotype Mapping for Small Sample Sizes

Objective: To establish associations between genetic variants and phenotypic outcomes in studies with limited sample sizes by integrating genotype and transcriptome data.

Methodology Overview: The GSPLS (Group lasso and SPLS model) method addresses the challenge of small sample sizes by incorporating biological network information to enhance statistical power [31]. This approach clusters genes using protein-protein interaction networks and gene expression data, then selects relevant gene clusters using group lasso regression.

Key Steps:

Data Preprocessing and Integration

- Obtain genotype data (SNP arrays or whole-genome sequencing) and transcriptome data (RNA-seq) from matched samples

- Preprocess genetic variants: filter based on minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.1) and impute missing genotypes

- Normalize gene expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., TMM for RNA-seq)

- Acquire tissue-specific expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) data from public repositories (e.g., GTEx Portal)

Gene Clustering Using Biological Networks

- Download protein-protein interaction (PPI) network data from curated databases (e.g., PICKLE Meta-database)

- Integrate PPI network with gene expression data to identify functionally coherent gene clusters

- Perform community detection on the integrated network to identify gene modules

Feature Selection Using Group Lasso

- Apply group lasso regression to select gene clusters associated with the phenotype of interest

- Optimize regularization parameters through cross-validation

- Map SNP clusters to selected gene clusters using eQTL information

Three-Layer Network Analysis

- Construct three-layer network blocks connecting SNP clusters, gene clusters, and phenotype

- Apply Sparse Partial Least Squares (SPLS) regression to model associations within each network block

- Generate final prediction by averaging results across all network blocks

Visualization Tools for Multi-Omics Data

The Pathway Tools Cellular Overview provides an interactive web-based environment for visualizing up to four types of omics data simultaneously on organism-scale metabolic network diagrams [32]. This tool automatically generates organism-specific metabolic charts using pathway-specific layout algorithms, ensuring biological relevance and consistency with established pathway drawing conventions.

Visual Channels for Multi-Omics Data:

- Reaction edge color: Typically used for transcriptomics data (e.g., gene expression levels)

- Reaction edge thickness: Often represents proteomics data or reaction fluxes

- Metabolite node color: Suitable for metabolomics data (e.g., metabolite abundances)

- Metabolite node thickness: Can represent additional metabolomics measurements or lipidomics data

Implementation Protocol:

- Data Preparation

- Format each omics dataset as a tab-separated table with identifiers matching those in the Pathway Tools database

- Ensure sample matching across omics datasets

- Normalize data appropriately for each omics type

Visualization Configuration

- Launch Cellular Overview from Pathway Tools

- Load multi-omics dataset files through the data upload interface

- Assign each omics dataset to the appropriate visual channel

- Adjust color and thickness mappings to optimize data representation

Interactive Exploration

- Use semantic zooming to reveal additional detail at higher magnification

- Employ animation features to visualize time-course data

- Generate omics pop-ups to view quantitative data for specific reactions or metabolites

Table 3: Comparison of Multi-Omics Visualization Tools

| Tool Name | Diagram Type | Multi-Omics Capacity | Semantic Zooming | Animation Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTools Cellular Overview | Pathway-specific algorithm | 4 simultaneous datasets | Yes | Yes |

| KEGG Mapper | Manual uber drawings | Single dataset painting | No | No |

| Escher | Manually created | Multiple datasets | Limited | No |

| PathVisio | Manual drawings | Single dataset | No | No |

| Cytoscape | General layout algorithm | Multiple datasets via plugins | No | Limited |

MiBiOmics for Exploratory Multi-Omics Analysis

MiBiOmics is an interactive web application that facilitates multi-omics data exploration, integration, and analysis through an intuitive interface, making advanced integration techniques accessible to researchers without programming expertise [30].

Key Functionalities:

Data Upload and Preprocessing

- Support for up to three omics datasets with shared samples

- Interactive filtering, normalization, and transformation options

- Outlier detection and removal capabilities

Exploratory Data Analysis

- Dynamic ordination plots (PCA, PCoA) for each omics dataset

- Relative abundance plots for taxonomic data

- Interactive sample coloring based on phenotypic traits

Network-Based Integration

- Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) implementation

- Module-trait association analysis

- OPLS regression for module validation

- Multi-omics hive plots for cross-omics visualization

Applications in Biomedical Research

Precision Medicine and Biomarker Discovery

Multi-omics integration has demonstrated particular value in precision medicine applications, where it enables the identification of molecular subtypes that transcend single-omics classifications. In oncology, integrated analysis of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data has revealed novel cancer subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes and therapeutic vulnerabilities [29].

Case Example: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Subtyping

- Objective: Identify molecular subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities

- Approach: Integrated analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from patient tumors

- Methods: Multi-staged analysis combining differential expression analysis with network-based integration

- Findings: Identification of four novel subtypes with distinct drug sensitivity profiles

- Clinical Impact: Enabled subtype-specific therapeutic recommendations beyond conventional classification

Functional Characterization of Genetic Variants

The integration of genotype data with transcriptomic and proteomic information has proven invaluable for moving beyond statistical associations to functional characterization of disease-associated genetic variants [31]. This approach helps bridge the gap between correlation and causation in complex disease genetics.

Implementation Framework:

- Prioritization of GWAS Hits - Identify significant associations between genetic variants and phenotypic traits

- Functional Annotation - Integrate eQTL and pQTL data to link associated variants with genes and proteins

- Pathway Contextualization - Map variant-gene-protein relationships onto biological pathways

- Experimental Validation - Design targeted experiments based on integrated multi-omics hypotheses

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

Data Quality and Preprocessing

The success of multi-omics integration critically depends on appropriate data preprocessing and quality control measures. Key considerations include:

- Batch Effect Management: Implement batch correction methods such as ComBat or Remove Unwanted Variation (RUV) when integrating datasets generated across different platforms or time points

- Missing Value Handling: Apply appropriate imputation methods tailored to each omics data type (e.g., k-nearest neighbors for proteomics data, missForest for metabolomics data)

- Data Transformation: Utilize variance-stabilizing transformations appropriate for each data type (e.g., log transformation for RNA-seq data, centered log-ratio transformation for compositional metabolomics data)

Method Selection Guidelines

The choice of integration method should be guided by the specific biological question, data characteristics, and analytical goals:

- Hypothesis Generation: Correlation-based networks and exploratory ordination techniques are ideal for initial data exploration and hypothesis generation

- Predictive Modeling: Machine learning approaches, particularly ensemble methods and deep learning, excel at developing predictive models from multi-omics data

- Mechanistic Insight: Network-based integration methods that incorporate prior biological knowledge are most suitable for deriving mechanistic insights

Statistical Power and Sample Size Considerations

While multi-omics integration can enhance biological insight, it also introduces statistical challenges related to high dimensionality and multiple testing:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Employ methods like WGCNA that reduce feature space while preserving biological information [30] [31]

- Cross-Validation: Implement rigorous cross-validation schemes to avoid overfitting, particularly with small sample sizes

- Multiplicity Control: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction across hypothesis tests while considering the dependency structure among omics features

The integration of multi-omics data represents a transformative approach for bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype. By simultaneously interrogating multiple molecular layers, researchers can construct more comprehensive models of biological systems and disease processes. The protocols and frameworks presented in this Application Note provide practical guidance for implementing these powerful approaches, from experimental design through computational analysis and biological interpretation.

As multi-omics technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, these integration strategies will play an increasingly central role in advancing biomedical research, precision medicine, and therapeutic development. The future of multi-omics integration lies in the continued development of methods that can not only handle the computational challenges of large, heterogeneous datasets but also generate biologically actionable insights that ultimately improve human health.

Navigating the Computational Toolbox: From Traditional to AI-Driven Integration Methods

In the field of multi-omics research, the ability to measure different molecular layers (genome, transcriptome, epigenome, proteome) at single-cell resolution has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and biological systems [33]. The strategic integration of these diverse data modalities is paramount for extracting meaningful biological insights that cannot be revealed through single-omics approaches alone. The integration landscape is primarily structured along two key taxonomic classifications: the nature of the biological sample source (Matched vs. Unmatched) and the methodological approach to data combination (Horizontal vs. Vertical Integration) [7]. This application note delineates these taxonomic frameworks, providing structured comparisons, experimental protocols, and practical toolkits to guide researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate integration strategies for their multi-omics studies.

Matched vs. Unmatched Data Integration

Conceptual Definitions and Data Relationships

The distinction between matched and unmatched data is foundational, as it dictates the choice of computational tools and integration algorithms [7].

- Matched Data: Different omics layers (e.g., transcriptome and epigenome) are measured simultaneously from the same individual cell [33]. Technologies enabling this include CITE-seq (RNA and protein), REAP-seq (RNA and protein), scM&T-seq (methylome and transcriptome), and the commercially available 10X Genomics Multiome (snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq) [33] [7]. The cell itself serves as the natural anchor for integration.

- Unmatched Data: Different omics layers are measured from different single-cell experimental samples [33]. This can involve different cells from the same sample, or different samples of the same tissue from different experiments [7]. Due to the lack of a direct cellular anchor, integration requires computational inference to find commonality between cells across modalities, often by projecting them into a co-embedded space [7].

Table 1: Characteristics of Matched vs. Unmatched Single-Cell Multi-Omics Data

| Feature | Matched Integration | Unmatched Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Same cell [33] | Different cells [33] |

| Technical Term | Vertical Integration [7] | Diagonal Integration [7] |

| Integration Anchor | The cell itself [7] | Computationally derived co-embedded space or biological prior knowledge [7] |

| Key Challenge | Technical variation between simultaneous assays; sparsity of some modalities (e.g., epigenomics) [33] | Higher source of variation from different cells and experimental setups; batch effects [33] |

| Primary Use Case | Directly studying relationships between different molecular layers within a cell (e.g., gene regulation) [33] | Leveraging vast existing single-modality datasets; studies where matched measurement is technically infeasible [33] |

Experimental Protocol for Generating Matched Multi-Omics Data

Protocol Title: Simultaneous Co-Measurement of Single-Cell Transcriptome and Epigenome using a Commercial Platform.

Objective: To generate a matched, multi-omics dataset from a single cell suspension, allowing for integrated analysis of gene expression and chromatin accessibility.

Materials:

- Fresh or Frozen Viable Cell Suspension: Ensure high cell viability (>90% for fresh, >70% for frozen nuclei).

- 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression Kit [33].

- Magnetic Stand: Suitable for 0.2 mL PCR tubes or 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes.

- SPRIselect Reagent Kit (Beckman Coulter) or equivalent.

- PCR Thermocycler.

- Bioanalyzer System (Agilent) or TapeStation for quality control.

- Illumina Sequencer (NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq 2000, etc.).

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension at a target concentration of 1,000–2,000 cells/μL in cold PBS + 0.04% BSA. Avoid fixation.

- For nuclei isolation (recommended for frozen tissues): Use a lysis buffer to isolate nuclei, followed by washing and resuspension in nuclei buffer [33].

- GEM Generation & Barcoding:

- Load the cell suspension, Master Mix, and Gel Beads onto a 10x Genomics Chromium chip.

- Within the Chip, each cell is co-encapsulated with a Gel Bead in a GEM (Gel Bead-In-Emulsion).

- Inside the GEM, two parallel reactions occur:

- ATAC Library: The transposase enzyme fragments accessible chromatin regions and adds a barcode unique to the cell.

- cDNA Library: Cells are lysed, and poly-adenylated RNA is reverse-transcribed with a cell barcode and a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI).

- Post GEM-Incubation Cleanup:

- Break the emulsions and pool the post-GEM reaction mixture.

- Use magnetic beads to clean up the reaction products.

- Library Construction:

- ATAC Library: Amplify the transposed DNA fragments via PCR using i5 and i7 sample indexes.

- cDNA Library: Perform cDNA amplification, followed by enzymatic fragmentation, end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. Finally, amplify the library with PCR using i5 and i7 sample indexes.

- Library QC and Sequencing:

- Quantify both libraries using a Bioanalyzer or TapeStation.

- Pool libraries at an appropriate molar ratio (e.g., 2:1 Gene Expression:ATAC) as per the manufacturer's guide.

- Sequence on an Illumina platform. Standard sequencing configurations are typically Paired-end, Dual Indexing: Gene Expression (28:10:10:90), ATAC (50:8:16:50).

Horizontal vs. Vertical Integration

Strategic Definitions in Multi-Omics

In the context of multi-omics, "Horizontal" and "Vertical" Integration describe the methodological approach to combining data, a distinction separate from the matched/unpaired nature of the samples [7].

- Horizontal Integration: The merging of the same omic type across multiple datasets [7]. While technically a form of integration, it is not considered true multi-omics integration but is a critical step for large-scale meta-analyses. For example, integrating scRNA-seq data from multiple studies or batches to create a unified reference atlas.

- Vertical Integration: The merging of data from different omics within the same set of samples [7]. This is the essence of multi-omics integration and is conceptually equivalent to working with matched data [7]. The goal is to build a cohesive view of the cellular state by combining complementary evidence from different molecular layers [33].

Table 2: Comparison of Horizontal and Vertical Integration Strategies in Multi-Omics

| Feature | Horizontal Integration | Vertical Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Merging the same omic across datasets [7] | Merging different omics within the same samples [7] |

| Equivalent To | Unmatched integration (when merging data from different cells) [7] | Matched integration [7] |