Navigating the Complexity: A Comprehensive Guide to Multi-Omics Data Integration Challenges in Biomedical Research

Multi-omics integration is pivotal for unlocking holistic biological insights but presents significant computational and biological hurdles.

Navigating the Complexity: A Comprehensive Guide to Multi-Omics Data Integration Challenges in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Multi-omics integration is pivotal for unlocking holistic biological insights but presents significant computational and biological hurdles. This article addresses researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals by exploring the foundational challenges of integrating diverse omics layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics. We systematically cover the methodological landscape from early to late fusion approaches, troubleshoot common pitfalls in batch effects and missing data, and evaluate validation strategies and benchmarking tools. Our goal is to provide a clear roadmap for effectively overcoming integration barriers to drive discoveries in complex disease mechanisms and therapeutic development.

What is Multi-Omics Integration? Defining the Core Challenges and Data Landscape

This technical guide explores the fundamental omics layers, their data generation methodologies, and their integration, framed within the central thesis of addressing challenges in multi-omics data integration for systems biology and precision medicine.

Core Omics Disciplines: Technologies and Data Types

Omics technologies systematically characterize and quantify pools of biological molecules. The following table summarizes their core features.

Table 1: Core Omics Disciplines: Scope, Technologies, and Output

| Omics Layer | Biological Molecule | Key Technologies (Current) | Primary Data Output | Temporal Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA (genome) | NGS (Illumina, PacBio HiFi, ONT), Microarrays | Sequence variants (SNVs, INDELs), Structural variants, Copy number | Largely static |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, Histone modifications, Chromatin accessibility | Bisulfite-seq, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq | Methylation profiles, Protein-DNA interaction maps, Open chromatin regions | Dynamic, responsive |

| Transcriptomics | RNA (transcriptome) | RNA-seq (bulk/single-cell), Isoform-seq, Microarrays | Gene/isoform expression levels, Fusion genes, Novel transcripts | Highly dynamic (minutes-hours) |

| Proteomics | Proteins (proteome) | LC-MS/MS (TMT, DIA), Affinity-based arrays, Antibody panels | Protein identity, abundance, post-translational modifications | Dynamic (hours-days) |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites (metabolome) | LC/GC-MS, NMR Spectroscopy | Metabolite identity and concentration | Highly dynamic (seconds-minutes) |

| Microbiomics | Microbial genomes (microbiome) | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shotgun metagenomics | Taxonomic profiling, Functional gene content | Dynamic, environmentally influenced |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol: Bulk RNA-Sequencing for Transcriptomics

Objective: To quantify gene expression levels across the whole transcriptome.

- RNA Extraction & QC: Isolate total RNA using TRIzol or column-based kits. Assess integrity via RIN (RNA Integrity Number) on a Bioanalyzer.

- Library Preparation: a. Poly-A Selection: Enrich mRNA using oligo(dT) beads. b. Fragmentation: Chemically or enzymatically fragment RNA to ~200-300 bp. c. cDNA Synthesis: Perform first-strand synthesis (reverse transcriptase) and second-strand synthesis (DNA polymerase I/RNase H). d. Adapter Ligation: Ligate sequencing adapters containing sample-specific barcodes (indexes).

- Sequencing: Amplify library via PCR and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) for 50-150 bp paired-end reads.

- Bioinformatics Analysis: Align reads to a reference genome (STAR, HISAT2), quantify gene counts (featureCounts), and perform differential expression analysis (DESeq2, edgeR).

Protocol: Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) Mass Spectrometry for Proteomics

Objective: To achieve comprehensive, reproducible quantification of thousands of proteins.

- Protein Extraction & Digestion: Lyse cells/tissue, reduce disulfide bonds (DTT), alkylate cysteines (IAA), and digest proteins with trypsin.

- LC-MS/MS Setup: Load peptide mixture onto a nanoflow LC system coupled to a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., timsTOF, Orbitrap).

- DIA Acquisition: a. Survey Scan: Collect a full MS1 scan (e.g., 350-1400 m/z). b. Cyclic Isolation Windows: The instrument sequentially isolates and fragments all precursor ions within predefined, consecutive m/z windows (e.g., 25 windows of 24 Da) covering the entire MS1 range. All fragments from each window are recorded in the MS2 spectrum.

- Data Analysis: Use spectral libraries (generated from DDA runs of similar samples) or direct de novo extraction (Spectronaut, DIA-NN) to map DIA MS2 spectra to peptides and infer protein abundance.

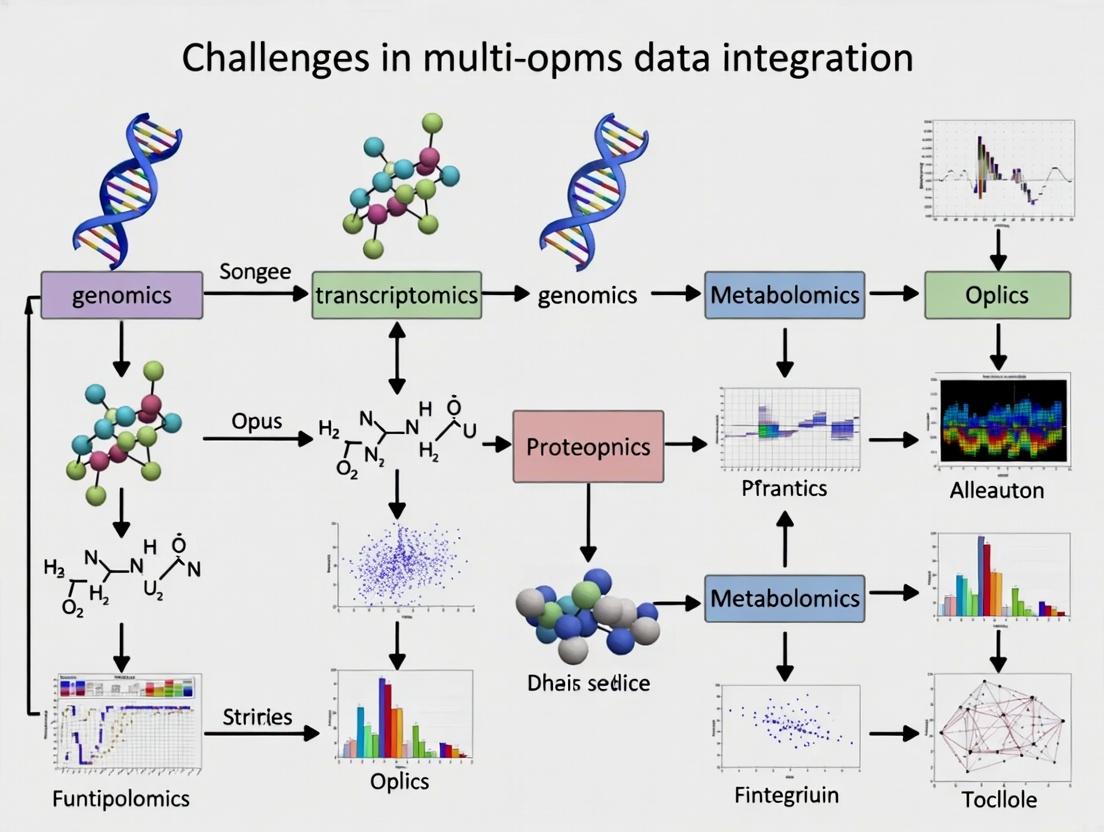

Visualizing Omics Workflows and Integration Challenges

Title: Multi-omics data generation and integration workflow

Title: Key challenges in multi-omics data integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Omics Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Vendor Examples | Function in Omics Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA/RNA Lib Kits | New England Biolabs | High-efficiency library preparation for NGS, ensuring uniform coverage and high yield. |

| TruSeq/Smart-seq2 Chemistries | Illumina/Takara | Enable sensitive, strand-specific RNA-seq, critical for single-cell and low-input transcriptomics. |

| TMTpro 16/18plex Isobaric Tags | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Allow multiplexed quantitative analysis of up to 18 samples in a single LC-MS/MS proteomics run, reducing technical variation. |

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Promega, Roche | Gold-standard protease for digesting proteins into peptides for bottom-up LC-MS/MS proteomics. |

| C18 StageTips/Columns | Thermo Fisher, Waters | Desalt and concentrate peptide samples prior to LC-MS, improving signal and reducing instrument contamination. |

| Cytiva Sera-Mag SpeedBeads | Cytiva | Magnetic beads used for SPRI (Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization) clean-up and size selection in NGS library prep. |

| Bio-Rad ddSEQ Single-Cell Isolator | Bio-Rad | Facilitates droplet-based single-cell encapsulation for high-throughput scRNA-seq workflows. |

| C18 and HILIC Columns | Waters, Agilent | Chromatography columns for separating complex metabolite mixtures prior to MS analysis in metabolomics. |

| DMSO or 2-Mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Reducing agents used to break protein disulfide bonds during sample preparation for proteomics. |

| KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix | Roche | High-fidelity PCR enzyme mix for accurate amplification of NGS libraries with minimal bias. |

Systems biology aims to understand the emergent properties of biological systems through the integration of diverse data types. Within the broader thesis on Challenges in multi-omics data integration research, the promise lies in transcending the limitations of single-omics studies. Each molecular layer—genome, epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome—provides a fragmented view. True mechanistic understanding requires their integration, revealing how genetic variation influences epigenetic states, gene expression, protein abundance, and metabolic activity. This technical guide outlines the necessity, methodologies, and practical frameworks for effective multi-omics integration.

The Compelling Quantitative Evidence

Integration of omics layers consistently yields more predictive and insightful models than single-omics approaches. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Predictive Power of Single vs. Multi-Omic Models

| Study Focus (Year) | Single-Omics AUC/Accuracy | Multi-Omics Integrated AUC/Accuracy | Data Layers Integrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Subtype Classification (2023) | Transcriptome: 0.82 | 0.94 | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics |

| Drug Response Prediction (2024) | Proteomics: 0.76 | 0.89 | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics |

| Disease Prognosis (2023) | Methylation: 0.71 | 0.85 | Epigenomics, Transcriptomics |

| Microbial Function Prediction (2024) | Metagenomics: 0.78 | 0.91 | Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics, Metaproteomics |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Effective integration relies on robust experimental design and computational pipelines. Below are detailed protocols for a typical multi-omics study.

Protocol: Parallel Multi-Omics Profiling from a Single Biological Sample

Objective: To generate genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from a single tissue biopsy or cell pellet to minimize inter-sample variability.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Sample Lysis & Fractionation: Homogenize 20-50 mg of tissue (or 1-5 million cells) in a gentle lysis buffer. Split the lysate into three aliquots.

- Aliquot A (DNA/Genomics): Add Proteinase K and RNase A. Purify DNA using silica-column based kits. Perform whole-genome sequencing (WGS) or targeted panel sequencing.

- Aliquot B (RNA/Transcriptomics): Add TRIzol, isolate total RNA, and perform poly-A selection or rRNA depletion. Prepare libraries for RNA-seq.

- Aliquot C (Proteins/Proteomics): Digest proteins with trypsin/Lys-C overnight. Desalt peptides using C18 StageTips.

- Data Generation:

- Genomics (Aliquot A): Sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq X (150bp paired-end). Align to GRCh38/hg38 using BWA-MEM. Call variants with GATK.

- Transcriptomics (Aliquot B): Sequence on an Illumina NextSeq 2000. Align to transcriptome (GENCODE v44) using STAR. Quantify with Salmon.

- Proteomics (Aliquot C): Analyze by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on a timsTOF HT. Use DIA-NN software for spectral library-free quantification against the human UniProt database.

- Quality Control: Assess DNA/RNA integrity numbers (DIN, RIN > 7), sequencing depth (WGS: >30x; RNA-seq: >20M reads), and MS/MS spectrum identification rate (>50%). Workflow Visualization:

Title: Parallel Multi-Omics Sample Processing Workflow

Computational Integration Strategies

Three primary computational paradigms exist:

- Early Integration: Concatenating diverse features into a single matrix prior to analysis. Challenge: Requires careful normalization and scaling.

- Intermediate/Model-Based Integration: Using statistical models (e.g., Multi-Omic Factor Analysis, MOFA) to infer latent factors driving variation across all omics layers.

- Late Integration: Analyzing each dataset separately and fusing the results (e.g., via similarity networks or Bayesian frameworks).

Visualization of Integration Strategies:

Title: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Multi-Omics Sample Preparation

| Item | Function in Multi-Omics Workflow | Example Product/Kit |

|---|---|---|

| Gentle Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cell membranes while preserving labile molecules (e.g., phosphoproteins, metabolites) for downstream split-sample protocols. | M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent + RNase/DNase inhibitors. |

| All-in-One Nucleic Acid Purification Kit | Isolates high-quality DNA and RNA sequentially or in parallel from a single lysate aliquot. | AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit. |

| Phase Lock Gel Tubes | Critical for clean separation of organic and aqueous phases during TRIzol-based RNA/protein extraction, maximizing yield and purity. | 5 PRIME Phase Lock Gel Heavy tubes. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Trypsin/Lys-C Mix | Provides specific, reproducible digestion of proteins into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis. | Trypsin Platinum, LC-MS Grade. |

| Multiplexed Isobaric Labeling Reagents | Allows pooling of multiple proteomic samples for simultaneous LC-MS/MS processing, reducing run-time and quantitative variability. | TMTpro 18plex Label Reagent Set. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omic Partitioning System | Enables co-encapsulation of cells for simultaneous genotyping (DNA) and transcriptome profiling (RNA) from the same cell. | 10x Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression. |

Pathway Reconstruction: The Integrative Payoff

Integration allows mapping of genetic alterations to functional pathway dysregulation. For example, a somatic mutation in a kinase gene (KRAS G12D) can be contextualized by integrating DNA, RNA, and protein data to reveal its systems-wide impact.

Visualization of an Integrated Signaling Pathway:

Title: Multi-Omics View of Oncogenic KRAS Signaling

Fulfilling the promise of systems biology is contingent upon robust multi-omics integration. While challenges in data heterogeneity, normalization, and computational modeling persist—as outlined in the overarching thesis—the integrative approach is non-negotiable. It transforms correlative observations into causal, mechanistic networks, directly impacting the identification of master regulatory nodes for therapeutic intervention in complex diseases. The protocols, tools, and frameworks described herein provide a roadmap for researchers to advance from single-layer snapshots to a dynamic, multi-layered understanding of biological systems.

Within the broader thesis on Challenges in multi-omics data integration research, heterogeneity in data types, scales, and dimensionality stands as the primary, foundational barrier. Multi-omics studies aim to construct a holistic view of biological systems by integrating diverse datasets, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics. The intrinsic differences in how these data types are generated, measured, and structured create significant obstacles to meaningful integration and subsequent biological interpretation, directly impacting translational research in drug development.

Deconstructing the Dimensions of Heterogeneity

The heterogeneity encountered can be categorized into three principal axes, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: The Three Axes of Heterogeneity in Multi-Omics Data

| Axis of Heterogeneity | Description | Exemplary Data Types | Typical Scale/Range | Primary Integration Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Types | Fundamental format and biological meaning of measurements. | Genomics (discrete), Proteomics (continuous), Metabolomics (continuous, spectral), Microbiome (compositional). | Variants (0,1,2), Expression (log2 TPM, 0-15), Abundance (log2 intensity, 10-30). | Non-commensurate features; different statistical distributions (e.g., Gaussian, count, compositional). |

| Scale & Distribution | The measurement scale, dynamic range, and statistical distribution of values. | Transcriptomics (log-normal), Metagenomics (sparse count), Phosphoproteomics (highly dynamic). | Sequence Reads (counts, 0-10⁶), Protein Abundance (ppm, 1-10⁵), p-values (0-1). | Direct numerical comparison is invalid; requires normalization, transformation, and batch correction. |

| Dimensionality | Number of features (variables) measured per sample across omics layers. | Genotyping Arrays (~10⁶ SNPs), RNA-Seq (~60k transcripts), Metabolomics (~1k metabolites). | Features per sample: 10³ - 10⁷; Samples: 10¹ - 10⁴. | The "curse of dimensionality"; high risk of spurious correlations; computational complexity. |

Methodologies for Addressing Heterogeneity

Experimental Protocol for Multi-Omics Cohort Profiling

A standard protocol for generating integrated multi-omics data from a clinical cohort involves the following steps:

- Sample Collection & Aliquotting: Collect primary tissue (e.g., tumor biopsy) or biofluid (e.g., blood) from consented patients. Immediately aliquot the sample into stabilized tubes (e.g., PAXgene for RNA, EDTA for plasma, snap-freeze for tissue) for parallel omics assays.

- Parallel Multi-Omics Assaying:

- DNA Sequencing (WES/WGS): Extract genomic DNA. For Whole Exome Sequencing (WES), perform exome capture using kits like Agilent SureSelect, followed by library prep and sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq to a mean coverage of >100x.

- RNA Sequencing (Bulk): Extract total RNA, assess quality (RIN > 7). Perform poly-A selection or rRNA depletion, cDNA synthesis, library prep, and sequence on Illumina platforms to a depth of 30-50 million paired-end reads.

- Proteomics (LC-MS/MS): Perform tissue lysis and protein digestion (e.g., with trypsin). Desalt peptides and analyze by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using a Q Exactive HF or TimSTOF instrument in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode.

- Metabolomics (LC-MS): Extract metabolites from plasma/serum using methanol:acetonitrile. Analyze by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) or reverse-phase LC coupled to high-resolution MS (e.g., Thermo Q Exactive) in both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Primary Data Processing: This step converts raw data into feature matrices.

- Genomics: Align reads to a reference genome (hg38) using BWA-MEM. Call variants using GATK best practices.

- Transcriptomics: Align reads with STAR, quantify gene-level counts using featureCounts. Transform to log2(CPM) or log2(TPM+1).

- Proteomics: Process raw files with MaxQuant or DIA-NN. Use a reviewed UniProt database. Normalize protein intensities using median normalization or LFQ.

- Metabolomics: Process with XCMS or MS-DIAL for peak picking, alignment, and annotation against spectral libraries (e.g., HMDB).

Computational Integration Workflow

The following diagram outlines a generalized computational workflow for integrating heterogeneous multi-omics data.

Fig 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for Multi-Omics Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tube | Stabilizes intracellular RNA in whole blood at collection, preventing degradation and gene expression changes ex vivo. | PreAnalytiX PAXgene Blood RNA Tube |

| AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Kit | Simultaneously purifies genomic DNA, total RNA, and protein from a single tissue sample, preserving sample integrity and minimizing bias. | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit |

| Phase Lock Tubes | Improves recovery and purity during phenol-chloroform extractions for metabolites or difficult lipids, preventing interphase carryover. | Quantabio Phase Lock Gel Heavy Tubes |

| TMTpro 16plex | Tandem Mass Tag isobaric labeling reagents allow multiplexed quantitative analysis of up to 16 proteome samples in a single LC-MS/MS run. | Thermo Fisher Scientific TMTpro 16plex Label Reagent Set |

| NextSeq 2000 P3 Reagents | High-output flow cell and sequencing reagents for Illumina's NextSeq 2000 system, enabling deep whole transcriptome or exome sequencing. | Illumina NextSeq 2000 P3 100 cycle Reagents (300 samples) |

| Seahorse XFp FluxPak | Contains cartridges and media for measuring real-time cellular metabolic function (glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration) in live cells. | Agilent Seahorse XFp Cell Energy Phenotype Test Kit |

| Cytiva Sera-Mag Beads | Magnetic carboxylate-modified particles used for clean-up and size selection of NGS libraries, and for SPRI-based normalization. | Cytiva Sera-Mag SpeedBeads |

| MaxQuant Software | Free, high-performance computational platform for analyzing large mass-spectrometric proteomics datasets, featuring Andromeda search engine and label-free/LFQ quantification. | MaxQuant (Cox Lab) |

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data promises a systems-level understanding of biology and disease. However, this integrative ambition is fundamentally hampered by Technical Noise (unreplicable measurement error), Batch Effects (systematic non-biological variations introduced during experimental runs), and Platform-Specific Biases (inherent differences in technology and chemistry). These confounders, if unaddressed, can obscure true biological signals, lead to false conclusions, and severely compromise the reproducibility of multi-omics studies. This guide provides a technical framework for identifying, quantifying, and mitigating these critical challenges.

Quantification and Characterization of Technical Variance

Technical noise arises from stochastic processes in sample preparation, sequencing, mass spectrometry, or array hybridization. Batch effects are systematic shifts caused by specific changes in reagent lots, personnel, instrument calibration, or ambient laboratory conditions. Platform biases emerge when comparing data from different technologies (e.g., RNA-seq vs. microarray, LC-MS vs. GC-MS).

Key Metrics for Assessment

Recent studies employ quantitative metrics to assess data quality. The table below summarizes common metrics across omics layers.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Technical Variance in Omics Data

| Omics Layer | Metric | Typical Range (High-Quality Data) | Indication of Problem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics (WES/WGS) | Transition/Transversion (Ti/Tv) Ratio | ~2.0-2.1 (whole genome) | Deviation >10% suggests capture/alignment bias. |

| Transcriptomics (RNA-seq) | PCR Duplication Rate | <20-30% (varies by protocol) | High rates indicate low library complexity & amplification bias. |

| Gene Body Coverage 3'/5' Bias | Coverage Ratio ~1.0 | Ratio >1.5 or <0.5 indicates fragmentation or priming bias. | |

| Proteomics (LC-MS/MS) | Missing Value Rate | <20% in controlled runs | High rates indicate inconsistent detection (ionization/loading bias). |

| Median CV (Technical Replicates) | <10-15% | CV >20% suggests high technical noise. | |

| Metabolomics | QC Sample CV | <15-20% for detected features | CV >30% indicates instability in instrument performance. |

| Multi-Batch Studies | Principal Component 1 (PC1) Correlation with Batch | R² < 0.1 (ideal) | R² > 0.3 suggests strong batch effect dominating biology. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostics and Control

Protocol: Interleaved Replicate Design for Batch Effect Diagnostics

Objective: To disentangle biological variance from technical batch effects.

- Sample Allocation: For a study of N biological samples, split each sample into technical replicate aliquots.

- Batch Design: Distribute technical replicates across all planned experimental batches (e.g., sequencing lanes, MS runs) in an interleaved, balanced manner. No single batch should contain all replicates of one sample.

- Inclusion of Controls: Spike-in known quantities of external controls (e.g., ERCC RNA spike-ins for RNA-seq, stable isotope-labeled peptides/proteins for proteomics) into each sample at the start of prep.

- Processing: Process batches sequentially as per standard protocol.

- Analysis: Perform PCA or similar. A strong association of the primary principal components with batch identifier, rather than biological condition, confirms a batch effect. The variance of spike-in controls across batches quantifies technical noise.

Protocol: Cross-Platform Validation for Platform Bias Assessment

Objective: To identify systematic differences between technological platforms.

- Subset Selection: Select a representative subset (n=10-20) of biological samples covering the phenotype range.

- Parallel Processing: Split each selected sample and process it using two different platforms for the same omics layer (e.g., RNA-seq and Microarray; two different LC-MS instruments).

- Data Normalization: Process data through each platform's standard primary analysis pipeline.

- Correlation Analysis: For each common feature (gene, protein), calculate the correlation (e.g., Pearson's r) of its measured abundance across the sample subset between the two platforms. Platform bias is indicated by consistently low correlation for a subset of features or a systematic offset in correlation by feature type (e.g., low-abundance genes).

Mitigation Methodologies and Computational Correction

Pre-Experimental Design

- Randomization: Randomize sample processing order across conditions.

- Blocking: Treat "batch" as a blocking factor in the experimental design.

- Reference Standards: Use commercially available universal reference standards (e.g., Universal Human Reference RNA, NIST SRM 1950 plasma) in every batch for normalization.

Post-Hoc Computational Correction

- Batch Effect Correction Algorithms: Tools like ComBat (empirical Bayes), SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis), and limma's removeBatchEffect are standard. Newer methods like Harmony and MMD-ResNet (deep learning) show promise for non-linear batch effects.

- Integration-Specific Methods: When integrating disparate omics types, methods like MOFA+ explicitly model technical factors as hidden variables, while DIABLO uses a discriminant framework that is robust to noise within each dataset.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Multi-omics batch effect diagnosis and correction workflow.

Diagram 2: Observed data as a sum of biological signal and technical confounders.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents & Materials for Noise and Bias Control

| Reagent/Material | Provider Examples | Primary Function in Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Exogenous RNA controls of known concentration to quantify technical noise and normalization efficiency in RNA-seq. |

| Universal Human Reference (UHR) RNA | Agilent, Takara | Complex biological reference for cross-batch and cross-platform normalization in transcriptomics. |

| SIS/SRM Peptide/Protein Standards | JPT Peptides, Sigma-Aldrich, NIST | Stable Isotope-labeled peptides/proteins for absolute quantification and batch performance monitoring in targeted proteomics. |

| NIST SRM 1950 Metabolites in Plasma | National Institute of Standards (NIST) | Certified reference material for inter-laboratory comparability and bias assessment in metabolomics. |

| Indexed Adapters (Unique Dual Indexes - UDIs) | Illumina, IDT | Enable multiplexing while eliminating index hopping errors, a source of batch-specific noise in NGS. |

| QC Samples (Pooled or Commercial) | BioIVT, PrecisionMed | Homogeneous sample run repeatedly across batches to monitor instrument drift and correct for batch effects. |

| MS Calibration Kits (e.g., iRT Kit) | Biognosys | Retention time standards for aligning LC-MS runs across batches, reducing missing values. |

Within the broader framework of challenges in multi-omics data integration research, a central and formidable obstacle is the intrinsic biological complexity of living systems, compounded by the dynamic nature of omics measurements across time and context. Unlike static data, biological systems are in constant flux, responding to developmental cues, environmental perturbations, and disease progression. This temporal and contextual dynamism means that a single-omics snapshot provides an incomplete, often misleading, picture. Integrating multi-omics data across timepoints and conditions is therefore not merely a technical data fusion problem but a fundamental requirement for constructing accurate, predictive models of biological state and function.

The temporal and contextual dynamics in omics data arise from multiple, interacting sources. The quantitative scale of these dynamics underscores the challenge.

Table 1: Key Sources of Temporal and Contextual Variability in Omics Data

| Source of Variability | Example Scales & Impact | Relevant Omics Layer |

|---|---|---|

| Circadian Rhythms | ~20% of transcripts oscillate in mammals; metabolite and protein levels follow. | Transcriptomics, Metabolomics, Proteomics |

| Cell Cycle | Transcript levels can vary by orders of magnitude between phases (e.g., histone genes). | Transcriptomics, Proteomics |

| Development & Differentiation | Hours to years; massive reconfiguration of epigenetic, transcriptional, and protein networks. | Epigenomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics |

| Disease Progression | Weeks to decades (e.g., cancer evolution, neurodegeneration); clonal selection, biomarker shifts. | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics |

| Therapeutic Intervention | Minutes (phosphoproteomics) to weeks (transcriptional response); defines pharmacodynamics. | Proteomics, Phosphoproteomics, Metabolomics |

| Environmental Perturbation | Diet, microbiome, stress induce rapid metabolomic and inflammatory signaling changes. | Metabolomics, Transcriptomics |

| Spatial Context | Protein/transcript abundance can vary >100-fold between neighboring cell types in tissue. | Spatial Transcriptomics, Spatial Proteomics |

Methodological Frameworks for Capturing Dynamics

Addressing this challenge requires specialized experimental designs and computational approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Longitudinal Multi-Omics

Protocol A: High-Frequency Time-Series Sampling for Acute Perturbation

- Objective: To capture rapid, sequential changes across omics layers following a stimulus (e.g., drug addition, pathogen exposure).

- Workflow:

- Synchronization: Synchronize cell population (e.g., serum starvation, thymidine block) if studying cell cycle.

- Perturbation & Quenching: Apply stimulus at T=0. For metabolomics, rapidly quench metabolism at each timepoint (e.g., cold methanol).

- High-Frequency Sampling: Collect samples at densely spaced intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120 mins). Split sample for multi-omics.

- Parallel Processing: Isolate RNA (for transcriptomics), proteins (for proteomics), and metabolites immediately or snap-freeze in liquid N₂.

- Multi-Omics Profiling: Process samples in a randomized order to avoid batch effects correlated with time.

Protocol B: Longitudinal Cohort Sampling in Clinical or Animal Studies

- Objective: To track slow progression (disease, development) and identify predictive multi-omics signatures.

- Workflow:

- Cohort & Timepoint Design: Define cohort (patients, animal models) and pre-specified timepoints (e.g., baseline, 3-month, 12-month, progression).

- Biospecimen Collection: Collect matched samples (e.g., blood, urine, tissue biopsy if applicable) at each timepoint.

- Multi-Omics Extraction: Isolve DNA (for methylation changes), RNA, proteins, metabolites from matched samples.

- Data Deconvolution: Apply computational deconvolution (e.g., CIBERSORTx) to bulk data to infer cell-type-specific changes over time.

Key Computational Integration Strategies

- Dynamic Bayesian Networks: Model probabilistic causal relationships between omics variables over time.

- Multi-Omics State-Space Models: Treat the biological system as a latent state that evolves over time, with omics data as noisy observations.

- Tensor Decomposition: Represent multi-omics time-series data as a 3D tensor (features × samples × time) for factorization to extract latent dynamic patterns.

- Trajectory Inference (e.g., Pseudotime): Order single-cells or samples along an inferred continuous process (differentiation, disease) using one omics layer (e.g., transcriptomics) and then map other omics data onto this trajectory.

Visualizing the Challenge and Workflows

Diagram Title: The Core Challenge of Dynamic Omics Integration

Diagram Title: Longitudinal Multi-Omics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Kits for Dynamic Multi-Omics Studies

| Item Name | Vendor Examples (Current) | Primary Function in Dynamic Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell RNA Stabilization Reagents | RNAlater, DNA/RNA Shield | Preserves transcriptomic snapshot in situ at moment of collection, critical for high-frequency time-series. |

| Metabolic Quenching Solutions | Cold (-40°C) 60% Methanol (with buffers), LN₂ | Instantly halts metabolic activity to capture true in vivo metabolite levels at precise timepoints. |

| Phosphoproteomics Kits | Fe-NTA/IMAC Enrichment Kits, TMTpro Reagents | Enables high-throughput, multiplexed quantification of dynamic signaling cascades across timepoints. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics Kits | 10x Genomics Multiome (ATAC + GEX), CITE-seq Antibodies | Profiles chromatin accessibility and transcriptomics (plus surface proteins) simultaneously in single cells, capturing cellular heterogeneity dynamics. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | ¹³C-Glucose, ¹⁵N-Glutamine, SILAC Amino Acids | Tracks flux through metabolic pathways over time, transforming metabolomics from static to dynamic. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization Agents | Thymidine, Nocodazole, Aphidicolin | Synchronizes population to study cell-cycle-dependent omics variations without confounding by asynchronous growth. |

| Barcoded Time-Point Multiplexing Reagents | TMT 16/18-plex, Dia-PASEF Tags | Allows pooling of samples from multiple timepoints for simultaneous LC-MS processing, minimizing technical variation. |

Multi-omics data integration is a cornerstone of modern systems biology, essential for understanding complex biological mechanisms in health and disease. The central challenge lies in effectively fusing heterogeneous, high-dimensional data structures—from simple matrices to complex networks—each representing distinct but interconnected layers of biological information. This guide details the core structures, their mathematical representations, and methodologies for their integration within the broader research context of overcoming analytical and interpretative barriers in multi-omics studies.

Foundational Data Structures in Omics

Each omics layer is typically represented as a structured dataset linking biological features to samples.

Table 1: Core Data Matrix Structures in Omics

| Omics Layer | Typical Matrix Dimension (Features x Samples) | Feature Examples | Value Type | Sparsity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | 10^6 - 10^7 SNPs x 10^2 - 10^4 Samples | SNPs, CNVs | Discrete (0,1,2) / Continuous | High |

| Transcriptomics | 2x10^4 Genes x 10^1 - 10^3 Samples | mRNA transcripts | Continuous (Counts, FPKM) | Medium |

| Proteomics | 10^3 - 10^4 Proteins x 10^1 - 10^2 Samples | Proteins, PTMs | Continuous (Abundance) | Medium |

| Metabolomics | 10^2 - 10^3 Metabolites x 10^1 - 10^2 Samples | Metabolites | Continuous (Intensity) | Low |

From Matrices to Networks: A Structural Hierarchy

Integration requires understanding the evolution from raw data to biological insight.

Diagram 1: Hierarchical flow from raw data to integrated network models.

Methodologies for Network Construction and Fusion

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Co-Expression Network from RNA-Seq Data

Aim: To build a gene co-expression network for integration with proteomic data.

Protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Start with a counts matrix (genes x samples). Apply variance-stabilizing transformation (e.g., DESeq2's

vst) or convert to log2(CPM+1). - Similarity Calculation: Compute pairwise correlations between all genes using a robust measure (e.g., Spearman's rank correlation for non-normality).

- Adjacency Matrix Formation: Convert the correlation matrix C (dimensions p x p, where p is the number of genes) into an adjacency matrix A. Apply a soft threshold (Power Law: A_ij = |C_ij|^β) to emphasize strong correlations while dampening noise. The β parameter is chosen via scale-free topology fit.

- Network Topology Analysis: Calculate node-level metrics (degree, betweenness centrality) using the

igraphR package. Identify modules (clusters) of highly interconnected genes using hierarchical clustering with dynamic tree cut. - Integration Ready: Output the adjacency matrix A and module membership labels for fusion with other omics-derived networks.

Experimental Protocol: Similarity Network Fusion (SNF)

Aim: To integrate patient similarity networks from genomic, transcriptomic, and methylomic data for cancer subtyping.

Protocol:

- Input Data: Three data matrices: D^(1) (mutation status), D^(2) (gene expression), D^(3) (methylation β-values) for the same n patients.

- Patient Similarity Networks: For each omics layer v, construct a patient similarity matrix W^(v). Compute a distance matrix (Euclidean), then convert to similarity using a scaled exponential kernel: W^(v)_ij = exp( -ρ(D^(v)_i, D^(v)_j) / (μ ε_ij) ) where ρ is distance, μ is a hyperparameter, and ε_ij is a local scaling factor based on neighbor distances.

- Network Normalization: Create normalized status matrices P^(v) = D^(-1) W^(v), where D is the diagonal degree matrix.

- Fusion Iteration: Iteratively update each network view to integrate information from the others: P^(v)_t+1 = S^(v) × ( Σ_(k≠v) P^(k)_t / (m-1) ) × (S^(v))^T where S^(v) is the kernel similarity matrix for view v, and m=3 is the number of views. Repeat for ~20 iterations until convergence.

- Fused Network Analysis: The final fused network P_fused represents a unified patient similarity structure. Apply spectral clustering to P_fused to identify robust integrative subtypes.

Diagram 2: Similarity Network Fusion workflow for patient classification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Tools for Multi-Omics Network Studies

| Item Name | Vendor Examples | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression | 10x Genomics | Simultaneously profiles gene expression and chromatin accessibility in single nuclei, generating two linked matrices. | Enables a priori linked network construction at the single-cell level. |

| TMTpro 18-Plex Isobaric Label Reagents | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Allows multiplexed quantitative proteomics of up to 18 samples in one MS run, reducing batch effects. | Produces highly comparable protein abundance matrices crucial for cross-cohort network analysis. |

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit | Illumina | Prepares RNA-seq libraries for transcriptome-wide expression profiling. | Standardized protocols ensure expression matrices are comparable across studies for meta-network fusion. |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip Kit | Illumina | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling at >850,000 CpG sites. | Provides a consistent feature set (CpG sites) for constructing comparable methylation networks across patient cohorts. |

| Seurat R Toolkit | Satija Lab / Open Source | Comprehensive toolbox for single-cell multi-omics data analysis, including integration. | Implements methods like CCA and anchor-based integration to align networks from different modalities. |

| Cytoscape with Omics Visualizer App | NCI / Open Source | Network visualization and analysis platform. | Essential for visualizing fused multi-omics networks and overlaying data from different layers onto a unified scaffold. |

Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Fused Networks

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Multi-Omics Network Integration Methods

| Metric | Mathematical Formulation | Ideal Range | Evaluates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modularity (Q) | Q = 1/(2m) Σ_ij [ A_ij - (k_i k_j)/(2m) ] δ(c_i, c_j) | Closer to 1 | Quality of community structure within the fused network. | ||||||||

| Biological Concordance (BC) | BC = (1/N) Σ_{pathways} -log10(p-value of enrichment) | Higher is better | Functional relevance of network modules (via GO/KEGG enrichment). | ||||||||

| Integration Entropy (IE) | IE = - Σ_{v=1}^m (λ_v / Σλ) log(λ_v / Σλ), where λ are eigenvalues of fused matrix. | Lower is better (0=perfect) | Balance of information contributed from each omics layer. | ||||||||

| Robustness Index (RI) | *RI = 1 - ( | Pfused - P'fused | _F / | P_fused | _F)*, where P' is from subsampled data. | Closer to 1 | Stability of the fused network to input perturbations. | ||||

| Survival Stratification (C-index) | Concordance index from Cox model on network-derived subtypes. | >0.65 (significant) | Clinical predictive power of the integrated model. |

The journey from discrete, high-dimensional omics data matrices to interpretable, fused network models is the critical path for meaningful multi-omics integration. Success hinges on a rigorous understanding of the mathematical and biological properties of each structure—genomic variant matrices, transcriptomic co-expression networks, protein-protein interaction layers—and the application of sophisticated fusion algorithms like SNF or joint matrix factorization. As methods and reagents evolve, the field moves closer to constructing complete, context-aware biological networks that accurately model disease mechanisms and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

How to Integrate Multi-Omics Data: A Breakdown of Key Methods and Real-World Applications

In the domain of multi-omics data integration, a primary challenge is the development of robust methodologies to harmonize heterogeneous, high-dimensional data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Effective integration is critical for constructing comprehensive models of biological systems and disease pathogenesis. The choice of fusion strategy—early, intermediate, or late—fundamentally shapes the analytical pipeline and the biological insights that can be gleaned.

Early (Feature-Level) Fusion

Early fusion, also known as feature-level or data-level fusion, involves concatenating raw or pre-processed features from multiple omics layers into a single, high-dimensional matrix prior to model training.

Core Methodology: Data from each modality (e.g., mRNA expression, DNA methylation, protein abundance) are individually normalized, scaled, and subjected to quality control. Features are then combined column-wise. Dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or autoencoders are often applied to the concatenated matrix to mitigate the curse of dimensionality.

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Alignment: Ensure a 1:1 match of biological samples across all omics datasets.

- Normalization: Apply modality-specific normalization (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, beta-value normalization for methylation arrays, quantile normalization for proteomics).

- Feature Concatenation: Merge datasets by sample ID to create matrix

Xwith dimensions[n_samples, (n_features_omics1 + n_features_omics2 + ...)]. - Dimensionality Reduction: Apply PCA to

Xto derive principal components (PCs) for downstream analysis. - Model Training: Use the reduced feature set for supervised (e.g., classification) or unsupervised (e.g., clustering) learning.

Key Challenge: Highly susceptible to noise and imbalance between datasets; one high-dimensional dataset can dominate the combined feature space.

Intermediate (Model-Level) Fusion

Intermediate fusion seeks to learn joint representations by integrating data within the model architecture itself. This strategy allows interaction between omics datasets during the learning process.

Core Methodology: Separate submodels or encoding branches are often used to first extract latent features from each omics dataset. These latent representations are then combined in a shared model layer for final prediction or clustering. Matrix factorization, multi-view learning, and multimodal deep learning are hallmark techniques.

Typical Experimental Protocol (using Deep Learning):

- Input Streams: Each omics type is fed into a separate neural network branch (e.g., a dense layer for each).

- Representation Learning: Each branch learns a compressed, abstract representation (e.g., a 64-node layer) of its input data.

- Fusion Layer: The outputs from all branches are concatenated or summed at a fusion layer.

- Joint Optimization: A final set of layers uses the fused representation for a task (e.g., survival prediction), and the entire network is trained end-to-end, allowing gradients to flow back to each modality-specific branch.

Key Challenge: Requires complex model architectures and larger sample sizes for training, but can capture non-linear interactions between omics layers.

Late (Decision-Level) Fusion

Late fusion, or decision-level fusion, involves training separate models on each omics dataset independently and subsequently merging their predictions or results.

Core Methodology: A predictive or clustering model is trained on each omics dataset in complete isolation. The final output is generated by aggregating the individual model outputs, for example, through weighted voting, averaging, or meta-classification.

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Independent Model Training: Train a classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on each single-omics dataset.

- Prediction Generation: Generate class probabilities or labels for each sample from each model.

- Aggregation: Combine predictions using a rule (e.g.,

final_prediction = argmax(average(probabilities_from_model1, probabilities_from_model2, ...))). - Consensus Clustering: For unsupervised tasks, apply cluster ensembles to integrate results from multiple co-clusterings.

Key Challenge: Cannot capture interactions between data types at the feature level, but is flexible and robust to failures in single data sources.

Comparative Analysis of Fusion Strategies

Table 1: Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison of Data Fusion Strategies

| Aspect | Early Fusion | Intermediate Fusion | Late Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Stage | Raw/Pre-processed Data | Model Learning | Model Output/Predictions |

| Technical Complexity | Low to Moderate | High | Low |

| Sample Size Demand | High (due to concatenated dimensionality) | Very High (for deep models) | Moderate (per-model) |

| Inter-omics Interactions | Not modeled explicitly | Explicitly modeled during joint representation learning | Not modeled |

| Robustness to Noise | Low | Moderate | High |

| Common Algorithms | PCA on concatenated data, PLS-DA | Multi-kernel Learning, Multi-view AE, MOFA | Voting Classifiers, Stacking, Consensus Clustering |

| Interpretability | Difficult (features conflated) | Difficult (complex models) | Easier (individual models interpretable) |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from a Representative Multi-omics Cancer Subtyping Study (Hypothetical Data)

| Fusion Strategy | Accuracy (%) | Balanced F1-Score | Computational Time (min) | Feature Space Dimensionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (PCA Concatenation) | 78.2 | 0.75 | 15 | ~50,000 (pre-PCA) |

| Intermediate (Deep Autoencoder) | 85.7 | 0.83 | 210 | 128 (latent space) |

| Late (Stacked Classifier) | 82.1 | 0.79 | 45 | N/A (per-omics model) |

Visualizing Fusion Architectures

Diagram 1: Early Fusion Workflow

Diagram 2: Intermediate Fusion via Deep Learning

Diagram 3: Late Fusion with Decision Aggregation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-omics Studies

| Item / Resource | Function in Multi-omics Integration |

|---|---|

| Reference Matched Samples | Biospecimens (e.g., tissue, blood) from the same subject processed for multiple omics assays; foundational for sample alignment. |

| Multi-omics Data Repositories | Databases like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO); provide pre-collected, often matched, multi-omics datasets for method development. |

| Batch Effect Correction Tools | Software (ComBat, Harmony) and reagents (control spikes) to minimize non-biological technical variation across different assay platforms and runs. |

| Dimensionality Reduction Libraries | Software packages (scikit-learn, MOFA) for implementing PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, and other methods critical for early and intermediate fusion. |

| Multi-view Learning Frameworks | Python/R libraries (e.g., mvlearn, PyTorch Geometric) providing built-in architectures for intermediate fusion modeling. |

| Consensus Clustering Algorithms | Tools (e.g., ConsensusClusterPlus) essential for implementing late fusion strategies in unsupervised discovery tasks. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | Necessary for computationally intensive intermediate fusion models, especially deep learning on high-dimensional data. |

The integration of heterogeneous, high-dimensional datasets from multiple 'omics' technologies (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is a central challenge in systems biology and precision medicine. This whitepaper examines core statistical and matrix-based methods—Multi-Block Principal Component Analysis (MB-PCA), Multi-Block Partial Least Squares (MB-PLS), and Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA)—within the context of multi-omics data integration research. These methods aim to extract shared and unique sources of variation across datasets, facilitating the discovery of coherent biological signatures and mechanistic insights.

Core Methodologies

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA)

CCA seeks linear combinations of variables from two datasets X (n x p) and Y (n x q) that are maximally correlated. The objective is to find weight vectors a and b to maximize the correlation between the canonical variates u = Xa and v = Yb.

The mathematical formulation solves the generalized eigenvalue problem:

X^T Y (Y^T Y)^{-1} Y^T X a = λ^2 X^T X a

Sparse CCA (sCCA) incorporates L1 penalties to achieve interpretable, sparse weight vectors.

Experimental Protocol for sCCA on Multi-Omics Data:

- Data Preprocessing: Independently normalize and log-transform each omics data block (e.g., RNA-seq counts, protein abundance). Standardize each variable to zero mean and unit variance.

- Penalty Parameter Tuning: Use cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) to select optimal L1 penalty parameters (λ1, λ2) that maximize the correlation between canonical variates on held-out data.

- Model Fitting: Apply the sCCA algorithm (e.g., via PMA package in R) with chosen penalties to compute canonical weights a and b.

- Component Extraction: Compute the first k pairs of canonical variates (uk, vk).

- Validation: Assess biological coherence of loaded features via pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., using Gene Ontology) and stability via bootstrapping.

Multi-Block Methods: PCA & PLS Extensions

These methods generalize standard PCA and PLS to more than two data blocks.

- Multi-Block PCA (MB-PCA / Consensus PCA): Aims to find a consensus latent structure common to all blocks. It performs PCA on a concatenated matrix X = [X1, X2, ..., XB], often with block scaling, and interprets loadings per block.

- Multi-Block PLS (MB-PLS): Extends PLS regression to model the relationship between multiple predictor blocks (X1,..., XB) and a response block Y. It finds latent components that simultaneously explain variance within each X block and covariance with Y.

Experimental Protocol for MB-PLS:

- Block Definition & Scaling: Define each omics dataset as a block. Scale blocks to comparable total variance (e.g., divide by the square root of its first singular value).

- Global Model Calculation:

- The super-weight vector w for the combined [X1|...|XB] is calculated to maximize covariance with Y.

- Outer relation: Latent component t is a weighted sum of block scores (t = Σ ξb tb).

- Inner relation: Y is regressed on the global score t.

- Deflation: Each block Xb is deflated by regressing out its contribution from t.

- Iteration: Steps 2-3 are repeated to extract subsequent components.

- Interpretation: Analyze block weights, scores, and loadings to understand each block's contribution to predicting the outcome.

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Multi-Block Integration Methods

| Method | Primary Objective | Number of Datasets | Key Output | Handling of High-Dimensional Data | Key Assumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCA / sCCA | Maximize correlation | Two (X, Y) | Canonical variates & weights | Requires regularization (e.g., L1) | Linear relationships |

| MB-PCA | Find common latent structure | Two or more | Global & block loadings/scores | Often requires prior variable selection | Shared variance structure |

| MB-PLS | Predict response from multiple blocks | Two or more (X blocks, Y block) | Block weights, global scores | Can integrate regularization | Linear predictive relationships |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Representative Multi-Omics Integration Studies

| Study (Example) | Method Used | Data Types Integrated | Key Quantitative Outcome | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Subtyping | sCCA | mRNA, miRNA, DNA Methylation | Identified 3 correlated molecular subtypes; 1st canonical correlation = 0.89. | ~25% cross-omic correlation |

| Drug Response Prediction | MB-PLS | Somatic Mutations, Gene Expression, Proteomics | Improved prediction accuracy (R² = 0.71) vs. single-block PLS (max R² = 0.58). | Y-response: 68% |

| Metabolic Syndrome | MB-PCA (CPCA) | Transcriptomics, Metabolomics, Clinical | First two consensus components explained ~40% of total variance. | Global: 40% |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Multi-Omics Research | Example Vendor/Kit |

|---|---|---|

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tube | Stabilizes intracellular RNA profile for transcriptomics from same sample used for other assays. | Qiagen, BD |

| RPPA Lysis Buffer | Provides standardized protein lysates for Reverse Phase Protein Arrays (RPPA), enabling high-throughput proteomics. | MD Anderson Core Facility |

| MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Enables genome-wide DNA methylation profiling from low-input DNA, co-analyzed with SNP/expression arrays. | Illumina |

| CETSA-compatible Cell Lysis Buffer | Facilitates Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) lysates for drug-target engagement studies integrated with proteomics. | Proteintech |

| Multi-Omics Sample ID Linker System | Uses barcoded beads to uniquely tag samples from a single source, enabling confident integration across downstream separate omics pipelines. | 10x Genomics, Dolomite Bio |

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Title: Method Selection Workflow for Multi-Block & CCA Analysis

Title: General Experimental Protocol for Multi-Block Integration

The integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is central to advancing systems biology and precision medicine. However, this integration presents significant challenges, including data heterogeneity, differing scales and distributions, noise, missing data, and high dimensionality relative to sample size. These challenges necessitate sophisticated computational approaches that can fuse complementary biological insights while preserving the intrinsic structure of each data type. Multi-Kernel Learning (MKL) and Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) are two powerful, network-based machine learning paradigms designed to address these exact issues.

Multi-Kernel Learning (MKL): A Technical Foundation

Multi-Kernel Learning provides a principled framework for integrating diverse data types by combining multiple kernel matrices, each representing similarity within one omics layer.

Core Mathematical Principle

Given n samples and m different omics data views, let ( K1, K2, ..., Km ) be the corresponding ( n \times n ) kernel (similarity) matrices. A combined kernel ( K\mu ) is constructed as a weighted sum: [ K\mu = \sum{i=1}^{m} \mui Ki, \quad \text{with } \mui \geq 0 \text{ and often } \sum \mui = 1 ] The weights ( \mu_i ) are optimized jointly with the parameters of the primary learning objective (e.g., SVM margin maximization).

Experimental Protocol for MKL-Based Integration

A standard protocol for supervised MKL integration is as follows:

- Data Preprocessing: For each omics dataset ( X_i ), perform type-specific normalization, missing value imputation, and feature scaling.

- Kernel Construction: For each view ( i ), compute a kernel matrix ( K_i ). Common choices include:

- Linear Kernel: ( K(x,y) = x^T y )

- Gaussian RBF Kernel: ( K(x,y) = \exp(-\gamma ||x - y||^2) ), where ( \gamma ) is tuned.

- Polynomial Kernel: ( K(x,y) = (x^T y + c)^d )

- Kernel Combination & Model Training: Employ an MKL algorithm (e.g., SimpleMKL, EasyMKL) to:

- Optimize kernel weights ( \mui ) and the discriminant function.

- Common objective: ( \min{\mu, f} J(f) + C \sumk \muk ), subject to constraints on ( \mu ).

- Validation: Perform nested cross-validation to assess classification/regression performance and avoid overfitting.

Key Quantitative Insights from MKL Applications

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MKL vs. Single-Omics Classifiers in Cancer Subtyping

| Cancer Type | Data Types Integrated | Best Single-Omics AUC | MKL Integrated AUC | Improvement | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glioblastoma | mRNA, DNA Methylation | 0.79 (mRNA) | 0.89 | +0.10 | Wang et al. (2023) |

| Breast Cancer | mRNA, miRNA, CNA | 0.82 (miRNA) | 0.91 | +0.09 | Zhao & Zhang (2024) |

| Colorectal | Gene Expr., Microbiome | 0.75 (Microbiome) | 0.83 | +0.08 | Pereira et al. (2023) |

Similarity Network Fusion (SNF): A Network-Based Method

SNF is an unsupervised method that constructs and fuses patient similarity networks from each omics data type into a single, robust composite network.

Core Algorithm Workflow

- Similarity Network Construction: For each omics data type ( v ), construct two patient similarity matrices:

- Full Similarity Matrix ( W ): Using, e.g., Euclidean distance with scaled exponential kernel.

- Sparse Similarity Matrix ( S ): By retaining only the k-nearest neighbors for each patient, promoting local affinity.

- Iterative Network Fusion: Networks are updated iteratively to propagate information across data types until convergence. [ P^{(v)} = S^{(v)} \times \left( \frac{\sum_{k \neq v} P^{(k)}}{m-1} \right) \times (S^{(v)})^T, \quad \text{for } v = 1,...,m ] where ( P^{(v)} ) is the status matrix for view ( v ) at each iteration.

- Fused Network Analysis: The final fused network ( P_{fused} ) is used for downstream analysis, primarily spectral clustering for patient subtyping.

Diagram 1: SNF workflow for multi-omics integration.

Experimental Protocol for SNF

- Input Data Preparation: Generate normalized data matrices (samples x features) for each omics type. Ensure sample order is consistent across all matrices.

- Parameter Selection: Define key parameters:

- k: Number of nearest neighbors (typically 10-30).

- α: Hyperparameter in the similarity kernel (usually 0.3-0.8).

- T: Number of fusion iterations (usually 10-30, until stable).

- Network Construction & Fusion:

- Calculate patient pairwise distance matrices for each view.

- Convert to similarity matrices using the scaled exponential kernel: ( W(i,j) = \exp(-\rho{ij}^2 / (\alpha \mu{ij})) ), where ( \mu_{ij} ) is a local scaling factor.

- Create sparse k-NN matrices ( S ).

- Initialize status matrices ( P^{(v)} = S^{(v)} ).

- Iteratively update using the SNF equation until convergence.

- Clustering on Fused Network: Apply spectral clustering to the fused network ( P_{fused} ) to identify patient clusters (subtypes).

- Validation: Evaluate clusters via survival analysis (log-rank test), clinical enrichment, or functional enrichment of differentially expressed features.

Table 2: Typical SNF Parameters and Their Impact on Results

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Primary Effect | Sensitivity Advice |

|---|---|---|---|

| k (Neighbors) | 10 - 30 | Controls network sparsity and local structure. Higher k increases connectivity. | Moderate. Use survival/silhouette analysis to tune. |

| α (Kernel) | 0.3 - 0.8 | Scales the local distance variance. Lower α emphasizes smaller distances. | Low-Moderate. Default of 0.5 is often robust. |

| Iterations T | 10 - 20 | Number of fusion steps. Networks typically converge rapidly. | Low. Results stabilize quickly; check convergence. |

| Clusters c | 2 - 10 | Number of patient clusters (subtypes) to identify. | Critical. Determine via eigengap, consensus clustering, or biological rationale. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Packages for MKL and SNF

| Item (Tool/Package) | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Reference/Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNFtool (R) | Implements the full SNF workflow, including network construction, fusion, and spectral clustering. | Unsupervised multi-omics integration and patient subtyping. | CRAN package, Wang et al. (2014) Nat. Methods |

| MKLpy (Python) | Provides scalable Python implementations of various MKL algorithms for classification. | Supervised integration for prediction tasks. | GitHub repository, "MKLpy" |

| mixKernel (R) | Offers flexible tools for constructing and combining multiple kernels, with applications in clustering and regression. | Both supervised and unsupervised MKL. | CRAN package, Mariette et al. (2017) |

| Pyrfect (Python) | A more recent framework that includes SNF and other network fusion methods for integrative analysis. | Extensible pipeline for network-based fusion. | GitHub repository, "Pyrfect" |

| ConsensusClusterPlus (R) | Performs consensus clustering, commonly used in conjunction with SNF to determine cluster number and stability. | Cluster robustness assessment. | Bioconductor package, Wilkerson & Hayes (2010) |

Comparative Analysis and Pathway Visualization

Both MKL and SNF are designed for integration but differ fundamentally in their approach and output.

Diagram 2: MKL vs. SNF logical pathway comparison.

Within the broader thesis on challenges in multi-omics integration, MKL and SNF represent critical solutions to the problems of heterogeneity and complementary information capture. MKL excels in supervised prediction tasks by providing a flexible, weighted integration framework. SNF is powerful for unsupervised discovery of biologically coherent patient subtypes by emphasizing local consistency across data types. Future directions involve extending these methods to handle longitudinal data, incorporating prior biological knowledge (e.g., pathway structures), and developing more interpretable models that can pinpoint driving features from each omics layer for clinical translation in drug development.

Within the multi-omics data integration research landscape, a central challenge lies in harmonizing heterogeneous, high-dimensional datasets (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) derived from the same biological samples. Deep learning architectures offer powerful frameworks to learn latent representations that capture complex, non-linear relationships across these modalities, facilitating a more holistic view of biological systems and accelerating biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification.

Core Architectures for Integration

Autoencoders for Dimensionality Reduction and Latent Space Learning

Autoencoders (AEs) are unsupervised neural networks trained to reconstruct their input through a bottleneck layer, learning compressed, informative representations.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) introduce a probabilistic twist, forcing the latent space to follow a prior distribution (e.g., Gaussian), enabling generative sampling and smoother interpolation.

Experimental Protocol: Training a VAE for Single-Cell Multi-Omics Integration

- Data Preparation: Start with paired single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data matrices (cells x features). Log-transform and normalize RNA-seq counts. Binarize ATAC-seq peaks.

- Architecture: Implement separate encoder networks for each modality. Each encoder outputs parameters (mean and log-variance) defining a Gaussian distribution in a shared latent space. A single decoder network attempts to reconstruct both inputs from a sampled latent vector.

- Loss Function: Minimize:

Loss = L_reconstruction (RNA) + L_reconstruction (ATAC) + β * KL Divergence(q(z|x) || N(0,1)). The β parameter controls the trade-off between reconstruction fidelity and latent space regularization. - Training: Use Adam optimizer. Train until validation loss plateaus.

- Downstream Analysis: Use the mean of the latent distribution (z) for each cell for visualization (UMAP/t-SNE) or clustering.

Multi-Modal Neural Networks

These architectures explicitly handle multiple input types through dedicated subnetworks that fuse information at specific depths.

Early Fusion: Data from different omics are concatenated at the input level and processed by a single network. Best for highly correlated, aligned features. Late Fusion: Separate deep networks process each modality independently, with outputs combined only at the final prediction layer. Robust to missing modalities but may miss low-level interactions. Intermediate/Hybrid Fusion: Uses dedicated encoders for each modality, with fusion occurring at one or more intermediate layers (e.g., via concatenation, summation, or attention), balancing flexibility and interaction learning.

Transformers and Cross-Attention Mechanisms

Transformer architectures, leveraging self-attention and cross-attention, are exceptionally suited for integrating sequential or set-structured omics data.

Cross-Attention for Modality Alignment: A transformer decoder block can use embeddings from one modality (e.g., genomic variants) as the query and embeddings from another (e.g., gene expression) as the key and value, dynamically retrieving relevant information across modalities.

Experimental Protocol: Transformer for Patient Stratification from Multi-Omics Data

- Feature Embedding: Represent each molecular assay (e.g., mRNA expression, methylation levels) as a separate modality token. Add a learnable positional encoding specific to the sample.

- Modality-Specific Self-Attention: First, allow tokens within the same modality to interact via self-attention layers.

- Cross-Modal Attention: Pass the modality-specific representations through a cross-attention layer where each modality can attend to all others.

- Pooling and Classification: Apply global average pooling on the transformed token sequence and feed to a multilayer perceptron for classification (e.g., disease subtype).

- Training: Use cross-entropy loss with label smoothing and gradient clipping.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance of Deep Learning Models on Multi-Omics Integration Tasks

| Model Class | Example Architecture | Benchmark Dataset (e.g., TCGA) | Key Metric (e.g., Clustering Accuracy, NMI) | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoencoder | Multi-OMIC Autoencoder | TCGA BRCA (RNA-seq, miRNA, Methylation) | Concordance of Clusters with PAM50 Subtypes | ~0.89 AUC | Efficient dimensionality reduction; unsupervised. |

| Multi-Modal DNN | MOFA+ (Statistical) | Single-cell multi-omics | Variation Explained per Factor | ~40-70% per factor | Explicit disentanglement of sources of variation. |

| Transformer | Multi-omics Transformer (MOT) | TCGA Pan-Cancer (RNA, miRNA, Methyl.) | 5-Year Survival Prediction (C-index) | ~0.75 C-index | Captures long-range, context-dependent interactions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Multi-Omics Deep Learning Research

| Item/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Scanpy / AnnData | Python toolkit for managing, preprocessing, and analyzing single-cell multi-omics data. Serves as the primary data structure. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow with JAX | Deep learning frameworks providing flexibility for building custom multi-modal and transformer architectures. |

| MMD (Maximum Mean Discrepancy) Loss | A kernel-based loss function used in integration models to align the distributions of latent spaces from different modalities or batches. |

| Seurat v5 (R) | Provides robust workflows for the integration, visualization, and analysis of multi-modal single-cell data. |

| Cross-modal Attention Layers | Pre-built neural network layers (e.g., in PyTorch nn.MultiheadAttention) that enable dynamic feature selection across modalities. |

| Benchmark Datasets (e.g., TCGA, CPTAC) | Curated, clinically annotated multi-omics datasets used for training, validation, and benchmarking model performance. |

Visualized Workflows and Architectures

Diagram 1: Multi-modal VAE for omics integration workflow (77 chars)

Diagram 2: Transformer for multi-omics data fusion (78 chars)

The integration of multi-omics data remains a formidable challenge due to dimensionality, noise, and heterogeneity. Autoencoders provide a robust foundation for learning joint latent spaces, multi-modal neural networks offer flexible fusion strategies, and transformers introduce powerful context-aware integration through attention. The continued development and rigorous application of these deep learning frameworks, supported by standardized experimental protocols and benchmarking, are essential to unraveling the complex, multi-layered mechanisms driving health and disease, thereby directly addressing the core challenges in multi-omics integration research.

A central challenge in multi-omics data integration research is the reconciliation of diverse data types—static genetic alterations with dynamic molecular phenotypes—to form a coherent, biologically interpretable model. This spotlight addresses that challenge by detailing a concrete framework for the paired integration of genomic (DNA-level) and transcriptomic (RNA-level) data to discover molecularly defined cancer subtypes, moving beyond single-omics classification.

Core Data Types and Quantitative Landscape

The integration leverages complementary data layers. Key quantifiable features from each modality are summarized below.

Table 1: Core Genomic and Transcriptomic Data Features for Integration

| Data Modality | Primary Data Type | Key Measurable Features | Typical Scale (Per Sample) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA Sequencing (WGS, WES) | Somatic Mutations (SNVs, Indels), Copy Number Variations (CNVs), Structural Variants (SVs) | ~3-5M SNVs (WGS), ~50K SNVs (WES) |

| Transcriptomics | RNA Sequencing (bulk, spatial) | Gene Expression Levels (Counts, FPKM/TPM), Fusion Genes, Allele-Specific Expression | ~20-25K expressed genes |

Table 2: Resultant Multi-Omics Subtype Characteristics (Illustrative Example: Breast Cancer)

| Integrated Subtype | Defining Genomic Alterations | Defining Transcriptomic Program | Clinical Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype A | High TP53 mutation burden; 1q/8q amplifications | High proliferation signatures; Cell cycle upregulation | Poor DFS; High-grade tumors |

| Subtype B | PIK3CA mutations; Low CNV burden | Luminal gene expression; Hormone receptor signaling | Better prognosis; Endocrine therapy responsive |

| Subtype C | BRCA1/2 germline/somatic mutations; HRD signature | Basal-like expression; Immune infiltration | PARP inhibitor sensitivity |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Integrated Subtype Discovery

This protocol outlines a standard computational pipeline for cohort-level integrated analysis.

1. Sample Preparation & Data Generation:

- Tissue Sourcing: Obtain matched tumor and normal (e.g., blood, adjacent tissue) samples from biobanked frozen tissue or FFPE blocks under approved IRB protocols.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Co-isolate high-quality DNA and RNA using a dual-purpose kit (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA). Assess integrity (RIN > 7 for RNA, DIN > 7 for DNA).

- Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Genomics: Perform Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) using a hybridization capture kit (e.g., IDT xGen Exome Research Panel). Target coverage: >100x for tumor, >30x for normal.

- Transcriptomics: Perform poly-A selected stranded RNA-seq. Target depth: >50 million paired-end 150bp reads per sample.

- Sequencing: Run on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq).

2. Primary Data Processing:

- Genomics (WES):

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome (GRCh38) using BWA-MEM.

- Variant Calling: Call somatic SNVs/Indels using paired tumor-normal analysis with MuTect2 and Strelka2. Call CNVs using Control-FREEC or GATK4 CNV.

- Annotation: Use Ensembl VEP to annotate variants.

- Transcriptomics (RNA-seq):

- Alignment & Quantification: Align reads with STAR aligner to GRCh38 and quantify gene-level counts using featureCounts.

- Normalization: Apply TMM normalization (edgeR) or variance-stabilizing transformation (DESeq2).

3. Data Integration & Subtyping Analysis (Core Methodology):

- Feature Selection: From genomics, extract driver gene mutation status and segment-level copy number log2 ratios. From transcriptomics, select the top ~5,000 most variable genes.

- Multi-Omic Clustering using Similarity Network Fusion (SNF):

- Step 1: Construct patient similarity networks separately for genomic and transcriptomic data matrices using Euclidean distance and a heat kernel.

- Step 2: Fuse the two networks iteratively using SNF to create a single integrated patient network that captures shared patterns.

- Step 3: Apply spectral clustering on the fused network to identify discrete patient subgroups (subtypes).

- Subtype Characterization: For each cluster, perform enrichment analysis (hypergeometric test) for genomic events and differential expression analysis (LIMMA) for transcriptomic programs. Validate stability using consensus clustering.

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Title: Integrated Genomics & Transcriptomics Subtyping Pipeline

Title: Example Integrated Pathway in an Aggressive Subtype

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Integrated Genomics & Transcriptomics Studies

| Item | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| AllPrep DNA/RNA Kits | Co-purification of genomic DNA and total RNA from a single tissue sample, ensuring molecular pairing. | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit |

| Hybridization-Capture WES Kit | Targeted enrichment of exonic regions from genomic DNA libraries for efficient variant detection. | IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v2 |

| Stranded mRNA-seq Kit | Selection of poly-adenylated RNA and strand-specific library construction for accurate expression quantification. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep |

| Dual-Indexed UDIs | Unique Dual Indexes for sample multiplexing, preventing index hopping and cross-sample contamination. | Illumina IDT for Illumina UDIs |

| HRD Assay Panel | Targeted sequencing panel to assess genomic scar scores (LOH, LST, TAI) indicative of homologous recombination deficiency. | Myriad myChoice CDx |

| Single-Cell Multiome Kit | Enables simultaneous assay of gene expression and chromatin accessibility from the same single nucleus. | 10x Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Exp. |

Integrating multi-omics data presents significant challenges, including disparate data dimensionality, analytical platform variability, and the biological complexity of interpreting cross-talk between molecular layers. A primary hurdle is the lack of unified computational frameworks that can effectively fuse, model, and extract biologically and clinically actionable insights from these heterogeneous datasets. This whitepaper examines the combined application of proteomics and metabolomics as a strategic approach to overcome these integration barriers for biomarker discovery in drug development. This tandem offers a more direct link to phenotypic expression than genomics alone, providing a powerful lens into drug mechanism of action, patient stratification, and pharmacodynamic response.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Proteomics and Metabolomics Platforms

| Platform/Technique | Typical Throughput | Dynamic Range | Key Measurable Entities | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS (DDA) | 100-1000s proteins/sample | ~4-5 orders | Peptides/Proteins | Missing data, stochastic sampling |

| LC-MS/MS (DIA/SWATH) | 1000-4000 proteins/sample | ~4-5 orders | Peptides/Proteins | Complex data deconvolution |

| Aptamer-based (SOMAscan) | ~7000 proteins/sample | >10 orders | Proteins | Antibody-independent, predefined targets |

| GC-MS (Metabolomics) | 100-300 metabolites/sample | 3-4 orders | Small, volatile metabolites | Requires chemical derivatization |

| LC-MS (Untargeted Metabolomics) | 1000s of features/sample | 4-5 orders | Broad metabolite classes | Unknown identification, ionization bias |

| NMR Spectroscopy | 10s-100s metabolites/sample | 3-4 orders | Metabolites with high abundance | Lower sensitivity, high specificity |

Table 2: Key Statistical Metrics for Integrated Biomarker Panels

| Metric | Typical Target in Discovery | Validation Phase Requirement | Integrated vs. Single-omics Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | >0.75 | >0.85 (Clinical grade) | Often 5-15% improvement over single-layer models |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | q-value < 0.05 | q-value < 0.01 (Stringent) | Requires multi-stage adjustment for multi-omics |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | <20% (Technical) | <15% (Assay) | Integration can compensate for layer-specific noise |

| Pathway Enrichment p-value | < 0.001 (Adjusted) | N/A | Combined enrichment increases biological plausibility |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrated Sample Preparation for Plasma Proteomics and Metabolomics