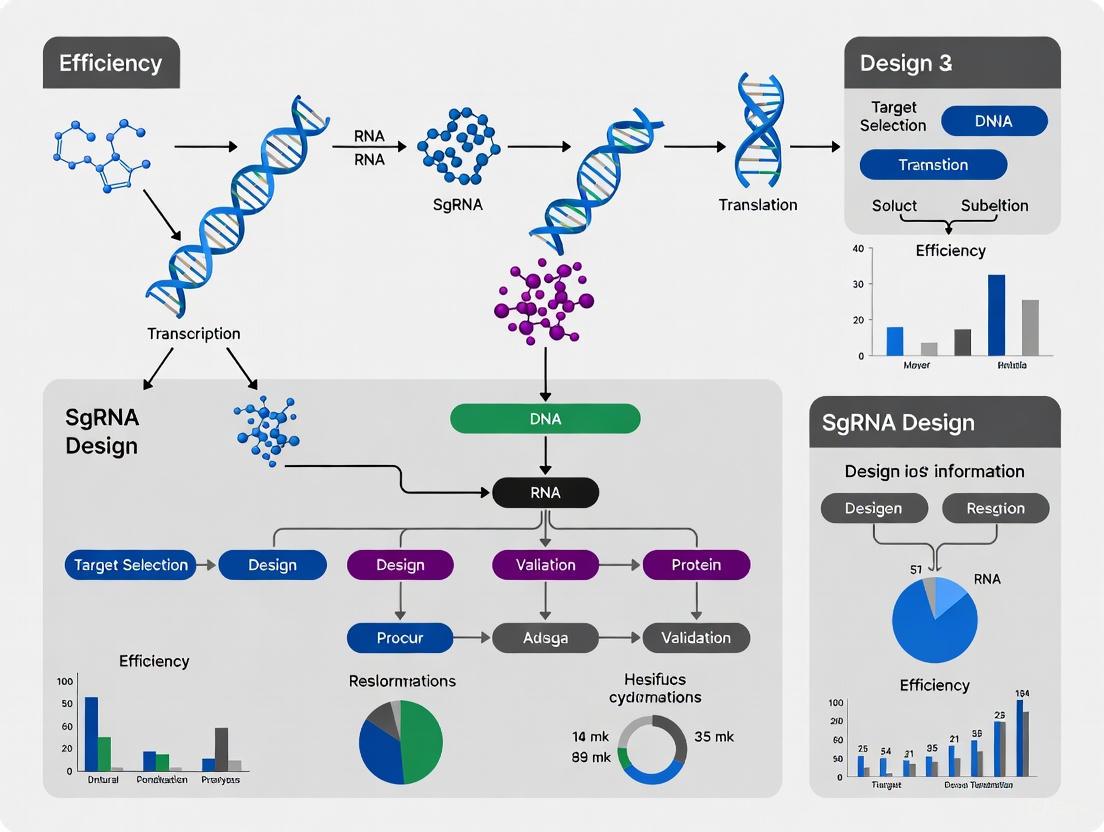

Optimizing sgRNA Design: Strategies to Maximize Efficiency and Minimize Off-Target Effects in CRISPR Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing.

Optimizing sgRNA Design: Strategies to Maximize Efficiency and Minimize Off-Target Effects in CRISPR Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. It covers foundational principles of sgRNA structure and function, advanced methodological design strategies, practical troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and empirical data, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance editing efficiency, improve specificity, and accelerate the translation of CRISPR technologies into therapeutic applications.

The sgRNA Blueprint: Understanding Core Components and Their Role in CRISPR-Cas9 Function

Core Biology: What are the fundamental roles of crRNA and tracrRNA in the CRISPR-Cas9 system?

In the native Type II CRISPR-Cas immune system from bacteria, the guide RNA exists as a duplex of two separate RNA molecules: the crRNA (CRISPR RNA) and the tracrRNA (trans-activating CRISPR RNA). Each has a distinct and critical function [1] [2].

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA): This molecule provides the targeting specificity for the Cas9 nuclease. It contains a custom-designed, ~20-nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to a specific target DNA sequence (the protospacer) in the genome. This spacer is flanked by a portion of the CRISPR repeat sequence [3] [2].

- tracrRNA (trans-activating CRISPR RNA): This molecule serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding. It is partially complementary to the repeat-derived portion of the crRNA. The tracrRNA is essential for the processing of the precursor crRNA (pre-crRNA) into its mature form by the endoribonuclease RNase III and facilitates the formation of the active Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex [2].

In laboratory applications, these two molecules are often fused into a single chimeric molecule called a single guide RNA (sgRNA) via a synthetic tetraloop linker. This sgRNA combines the targeting function of the crRNA with the Cas9-binding function of the tracrRNA, simplifying delivery and use [3] [4].

Experimental Troubleshooting: Why might my CRISPR editing efficiency be low, and how can I address it?

Low editing efficiency is a common challenge. The choice between using a two-part guide RNA system (crRNA + tracrRNA) or a single guide RNA (sgRNA) can be a significant factor [1].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Editing Efficiency

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA Format | The chosen guide RNA format (two-part vs. single) is suboptimal for your specific target site [1]. | Test the alternative format; for 255 target sites, two-part performed better for 26.7%, sgRNA for 16.9%, and 56.4% worked equally well [1]. |

| Guide RNA Stability | Degradation of the guide RNA by cellular nucleases, especially in environments with high nuclease activity [1]. | Use chemically synthesized, modified sgRNAs or Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT for enhanced stability [1]. |

| Cas9 Delivery Method | The guide RNA format is not optimal for the chosen Cas9 delivery method [1]. | Use a two-part guide RNA or sgRNA for direct RNP delivery. For indirect delivery (mRNA/plasmid), use sgRNAs for longer stability in the cell [1]. |

| sgRNA Scaffold | Use of a non-optimized, original sgRNA scaffold [4]. | Use an efficiency-enhanced scaffold variant (e.g., Flip+Extension, optimized sgRNA) instead of the original canonical scaffold [4]. |

| Spacer Sequence | The specific 20-nt spacer sequence has low intrinsic activity [5]. | Design and test 3-4 different sgRNAs per gene to account for unpredictable performance variability [5]. |

Reagent Solutions: What key reagents are essential for working with crRNA and tracrRNA?

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for crRNA/tracrRNA Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Chemically Modified crRNA/tracrRNA (e.g., Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT) | Increases resistance to nucleases, improving editing efficiency and consistency, especially in sensitive cells or for RNP delivery [1]. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | High-purity, chemically synthesized guides that offer high editing efficiency and reduced labor compared to in vitro transcription (IVT) [3]. |

| In Vitro Transcription (IVT) Kit (e.g., Guide-it sgRNA In Vitro Transcription Kit) | Allows lab production of sgRNAs from a DNA template; requires purification and quality control [6]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA transcripts (like IVT sgRNAs) from degradation during synthesis and handling [3]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle for in vivo CRISPR therapy, enabling systemic delivery and even re-dosing of editing components [7]. |

Experimental Protocols: How do I set up key experiments comparing two-part and single guide RNAs?

Protocol: Direct Comparison of crRNA/tracrRNA vs. sgRNA Editing Efficiency

This protocol is adapted from large-scale comparisons that empirically determine the most effective guide RNA format for a given target site [1].

Design and Synthesis:

- For your target genomic locus, design a single 20-nucleotide spacer sequence.

- Synthesize this sequence in two formats:

- Two-part system: As a separate crRNA molecule and a universal tracrRNA molecule.

- Single-guide system: As an sgRNA, where the same spacer is fused to the tracrRNA scaffold via a tetraloop.

- For highest efficiency and stability, use chemically synthesized RNAs with proprietary modifications.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation:

- For the two-part system: Pre-complex the crRNA and tracrRNA at equimolar ratios to form the guide RNA duplex.

- For the sgRNA system: Use the sgRNA directly.

- Incubate the respective guide RNA(s) with purified Cas9 protein to form the active RNP complex.

Cell Delivery and Culture:

- Deliver the pre-formed RNP complexes into your target cells (e.g., Jurkat cells) using an appropriate method such as electroporation.

- Culture the cells for a sufficient period (e.g., 3-7 days) to allow for genome editing and expression of the phenotype.

Efficiency Analysis:

- Harvest genomic DNA from the edited cell population.

- Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze editing efficiency using next-generation sequencing (NGS) or the T7E1 assay.

- Quantify the percentage of indels at the target site for each guide RNA format.

Protocol: Validating sgRNA Efficiency Prior to Cell Transduction

This protocol uses an in vitro cleavage assay to pre-screen multiple sgRNAs, saving time and resources [6].

sgRNA Design and In Vitro Transcription:

- Design 3-4 different sgRNAs targeting different regions of your gene of interest.

- Generate the sgRNAs using an in vitro transcription (IVT) kit (e.g., Guide-it sgRNA In Vitro Transcription Kit), which uses a PCR-amplified DNA template with a T7 promoter.

In Vitro Cleavage Assay:

- Purify the synthesized sgRNAs to remove reaction byproducts.

- Incubate each sgRNA with Cas9 nuclease and a purified DNA substrate containing the target site.

- Run the reaction products on a gel to separate cleaved from uncleaved DNA.

Analysis and Selection:

- Quantify the cleavage efficiency for each sgRNA. The sgRNA that leads to the most complete cleavage of the target substrate is the most effective.

- Proceed with the top-performing sgRNA for your cell-based experiments.

FAQ: Addressing Common Technical Questions

Q1: In a CRISPR screen, why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene perform differently? Gene editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each unique sgRNA spacer sequence, such as local chromatin accessibility and sequence-specific factors. Therefore, different sgRNAs for the same gene often show variable activity. It is recommended to design at least 3-4 sgRNAs per gene to ensure robust results [5].

Q2: When should I choose a two-part guide RNA system over a single guide RNA? Consider a two-part system (crRNA + tracrRNA) when [1]:

- You are working with a limited budget, as shorter oligos are less expensive to synthesize.

- You are delivering CRISPR components as a pre-formed RNP complex.

- You have encountered low editing efficiency with an sgRNA and want to test an alternative.

Q3: What is the most critical part of the sgRNA for determining its target? The ~20-nucleotide spacer sequence at the 5' end of the sgRNA (derived from the crRNA) is solely responsible for target specificity. This sequence must be complementary to your target DNA site, which must be located immediately 5' of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [8] [6].

Q4: How can I improve the stability of my guide RNAs? Use chemically synthesized guide RNAs with backbone modifications. These modifications protect against degradation by endogenous exo- and endonucleases, leading to higher editing efficiency, especially in challenging cell types or for in vivo applications [1] [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, and what is the specific function of sgRNA?

The CRISPR-Cas9 system requires two core components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [3] [8]. The single guide RNA (sgRNA) is a synthetic fusion of two naturally occurring RNA molecules: the crispr RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [3]. The sgRNA's function is to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a specific DNA locus. Its 5' end contains a customizable ~20-nucleotide spacer sequence (derived from crRNA) that is complementary to the target DNA site. Its 3' end forms a scaffold structure (derived from tracrRNA) that is essential for binding to the Cas9 protein [3] [9]. In summary, the sgRNA acts as a homing device, providing the system with its remarkable programmability.

Q2: What are the key sequence requirements in the DNA for a successful sgRNA-guided Cas9 cut?

For Cas9 to recognize and cleave a DNA sequence, two key conditions must be met [8]:

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): The target DNA must contain a short, specific sequence immediately adjacent to the region complementary to the sgRNA's spacer. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide [3] [8].

- Complementary Target Sequence: The ~20 nucleotides upstream of the PAM must be complementary to the 5' end of the sgRNA [9]. The Cas9-sgRNA complex will not bind or cleave efficiently if the homology is insufficient.

Q3: Why does my CRISPR experiment have low editing efficiency, and how can I improve it?

Low editing efficiency can stem from several factors. The table below outlines common causes and their solutions.

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Design | Low sequence accessibility or misfolded sgRNA [10] | Use design tools to check folding kinetics; select sgRNAs with low folding energy barriers (<10 kcal/mol) [10]. |

| Suboptimal spacer sequence [11] | Select sgRNAs with high predicted on-target activity scores (e.g., >0.6 using models like Doench 2016) [11]. | |

| Delivery & Expression | Inefficient delivery into cells [12] | Optimize transfection method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection) for your specific cell type [12]. |

| Weak promoter driving expression [12] | Use a strong, cell-type-appropriate promoter for expressing Cas9 and sgRNA. | |

| Biological Context | Target site buried in chromatin | Consider using Cas9 variants with enhanced activity. The PAM requirement may also limit targetable sites [8]. |

Q4: How can I minimize off-target effects in my experiments?

Off-target effects, where Cas9 cuts at unintended genomic sites, are a major concern [13]. You can employ a multi-pronged strategy to minimize them:

- Optimize sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs with high specificity. Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP, Synthego's tool) to select sgRNAs with minimal homology to other genomic regions, especially in the "seed sequence" near the PAM [3] [8]. Aim for a high specificity score [11].

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Replace wild-type Cas9 with engineered, high-fidelity versions such as eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, or HypaCas9. These mutants reduce off-target cleavage by weakening non-specific interactions with DNA [8].

- Modify Experimental Conditions: Using Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes (pre-assembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA) instead of plasmid DNA can reduce the time the nuclease is active in the cell, thereby limiting off-target opportunities [14].

- Utilize Paired Nickases: Use a Cas9 nickase (Cas9n) that only cuts one DNA strand. By delivering two sgRNAs that target opposite strands and adjacent sites, you can create a double-strand break only at the intended locus, dramatically increasing specificity [8] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Persistent Off-Target Activity

Despite a well-designed sgRNA, off-target edits are detected in your validation assays.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Confirm Off-Targets: Use targeted sequencing or mismatch detection assays (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I) on the predicted off-target sites from design tools [13].

- Switch Cas9 Variant: If off-targets are confirmed, switch to a high-fidelity Cas9 like eSpCas9(1.1) or HypaCas9 [8].

- Use RNP Delivery: Deliver CRISPR components as pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. This shortens the exposure time of the genome to the nuclease and has been shown to reduce off-target effects [14].

- Validate with a Negative Control: Always include a control treated with a non-targeting sgRNA to distinguish specific edits from background noise [12].

Problem: Inefficient Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

While non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) works well, you are struggling to introduce precise edits via HDR using a donor DNA template.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Optimize Template Delivery: Ensure your donor template (single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide or double-stranded DNA) is delivered in high molar excess relative to the Cas9-sgRNA RNP complex.

- Synchronize Cell Cycle: HDR is most active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [9]. Use chemicals to synchronize your cell population at these phases to boost HDR efficiency.

- Modulate Repair Pathways: Consider using small molecule inhibitors of key NHEJ proteins (e.g., KU70) to tilt the balance of DNA repair toward the HDR pathway [14].

- Adjust sgRNA Positioning: Design the sgRNA so that the Cas9 cut site is as close as possible to the desired edit. HDR efficiency drops significantly as the distance from the break increases.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing On- and Off-Target Editing Efficiency

This protocol uses next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantitatively measure editing success and specificity [13].

Materials:

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and high-fidelity DNA polymerase

- NGS library preparation kit

- Bioinformatics pipeline for indel analysis

Method:

- Harvest Genomic DNA: Extract genomic DNA from CRISPR-treated cells and a negative control population.

- Amplify Target Loci: Design PCR primers to amplify the on-target locus and the top ~10-20 predicted off-target loci. Include Illumina adapter sequences in the primers.

- Prepare NGS Library: Purify the PCR amplicons and prepare them for sequencing according to your NGS kit's instructions.

- Sequence and Analyze: Run the samples on a sequencer. Use a bioinformatics tool to align reads to the reference genome and calculate the percentage of reads with insertions or deletions (indels) at each site.

- Interpret Results: High indel frequency at the on-target site indicates good efficiency. Indels at other sites are off-target events. Compare treated and control samples to filter out background noise.

Protocol 2: Testing sgRNA Efficacy Using a T7 Endonuclease I Assay

This is a cost-effective, gel-based method to quickly confirm genome editing before moving to NGS [15].

Materials:

- T7 Endonuclease I enzyme

- PCR reagents

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

Method:

- Amplify Target Site: PCR-amplify a ~500-800 bp region surrounding the sgRNA target site from treated and control cell DNA.

- Denature and Reanneal: Purify the PCR product. Heat-denature it and then slowly reanneal it. This allows strands from differently edited alleles to form heteroduplexes with mismatches at the indel sites.

- Digest with T7 Endonuclease I: Incubate the reannealed DNA with the T7 Endonuclease I, which recognizes and cleaves the heteroduplex mismatches.

- Visualize and Quantify: Run the digested products on a gel. Cleaved bands indicate successful editing. The efficiency can be estimated from the band intensities using specialized formulas [15].

sgRNA Directed Cas9 Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting CRISPR-Cas9 experiments focused on sgRNA mechanism and efficiency.

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) | Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target effects [8]. | Critical for applications requiring high specificity, such as therapeutic development. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically synthesized, high-purity single-guide RNA [3]. | Offers higher consistency and editing efficiency compared to plasmid-based expression; ideal for RNP delivery [3]. |

| Cas9 Nickase (Cas9n-D10A) | Mutant Cas9 that cuts only one DNA strand [8]. | Used with paired sgRNAs to create targeted double-strand breaks with minimal off-target effects [8] [11]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Enzyme that detects base pair mismatches in heteroduplex DNA [15]. | A fast and cost-effective method for initial validation of editing efficiency. |

| Surveyor Nuclease | Another mismatch-specific endonuclease used for indel detection [13]. | An alternative to T7 Endonuclease I for confirming genome edits. |

| dCas9 (Catalytically Inactive Cas9) | Mutant Cas9 (D10A, H840A) that binds DNA without cutting [8]. | Used for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa) for transcriptional control [8] [13]. |

The Role of the PAM in CRISPR-Cas Systems

What is a PAM and why is it indispensable for CRISPR editing?

The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows immediately after the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR-Cas system [16]. This sequence is an absolute requirement for most Cas nucleases to recognize and cut target DNA [17]. The PAM sequence is not part of the guide RNA but must be present in the genomic DNA immediately downstream of the target site [17].

In bacterial adaptive immunity - the natural origin of CRISPR systems - the PAM serves a crucial protective function: it enables Cas proteins to distinguish between foreign viral DNA (which contains PAM sequences) and the bacterium's own DNA (which lacks PAM sequences adjacent to stored viral fragments in the CRISPR array) [16]. This self versus non-self discrimination prevents bacteria from targeting and destroying their own genome [16].

What is the molecular mechanism of PAM-dependent cleavage?

When a Cas nuclease searches for potential target sites, it first scans DNA for PAM sequences [16]. Upon identifying a valid PAM, the enzyme partially unwinds the DNA duplex, allowing the guide RNA to attempt pairing with the target DNA strand [8]. If sufficient complementarity exists between the guide RNA and target DNA - particularly in the critical "seed sequence" near the PAM - the Cas nuclease becomes activated and creates a double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [16] [8].

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental relationship and workflow:

PAM Requirements for Different CRISPR Systems

What are the PAM sequences for commonly used Cas nucleases?

Different Cas nucleases isolated from various bacterial species recognize distinct PAM sequences [16]. The table below summarizes PAM requirements for commonly used CRISPR nucleases:

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Commonly Used Cas Nucleases

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Source | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG (where N is any base) [16] [17] [8] | Most widely used nuclease; abundant PAM sites |

| SpCas9-NG | Engineered from SpCas9 | NG [8] | Expanded PAM flexibility |

| SpRY | Engineered from SpCas9 | NRN > NYN (R = A/G; Y = C/T) [8] | Near PAM-less activity |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN [16] | Smaller size for viral delivery |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT [16] | High specificity; longer PAM |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC (R = A/G; Y = C/T) [16] | Compact size |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV (V = A/C/G) [16] | Creates staggered cuts; no tracrRNA needed |

| Cas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN [16] | Thermostable variant available |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN [16] | High-fidelity variant |

| xCas-3.7 | Engineered from SpCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT [8] | Broad PAM recognition |

How do engineered Cas variants expand PAM compatibility?

Protein engineering has created Cas variants with altered PAM specificities to overcome the targeting limitations of wild-type nucleases [8]. These "PAM-flexible" or "PAM-less" Cas enzymes include:

- xCas9: Recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs with increased fidelity [8]

- SpCas9-NG: Engineered to recognize NG PAMs instead of NGG [8]

- SpG: Recognizes NGN PAMs with improved activity [8]

- SpRY: Recognizes NRN and NYN PAMs, approaching PAM-less behavior [8]

These engineered variants significantly expand the targeting range of CRISPR systems, enabling editing of previously inaccessible genomic regions [8].

Troubleshooting PAM-Related Experimental Failures

Why does my CRISPR experiment show no editing activity?

Problem: No cleavage activity despite proper gRNA design and expression.

Potential causes and solutions:

- Incorrect PAM identification: Verify your target sequence includes the correct PAM for your specific Cas nuclease immediately following the target site [16] [17]. Use PAM prediction tools during gRNA design.

- PAM sequence not present: Confirm the genomic locus contains the required PAM sequence. If not, consider alternative Cas proteins with different PAM requirements [16].

- PAM accessibility issues: Chromatin structure or DNA methylation may occlude PAM recognition. Test multiple gRNAs targeting different regions near your desired edit [16].

- Wrong nuclease selection: Ensure you're using the Cas protein matching your experimental PAM requirements. For example, don't use SpCas9 (requires NGG) for targets with only TTTV PAMs [16].

Why is my editing efficiency low even with a valid PAM?

Problem: Weak editing efficiency despite confirmed PAM presence.

Potential causes and solutions:

- Suboptimal PAM context: Not all PAM sequences work equally well. For SpCas9, NGG is optimal, but NAG and NGA show reduced efficiency [18]. If possible, choose targets with optimal PAMs.

- Spacer sequence effects: The spacer sequence itself can influence PAM preference and cleavage efficiency [18]. Design multiple gRNAs with different spacers but identical PAMs.

- PAM-distal mismatches: While Cas9 tolerates mismatches farther from the PAM, they can still reduce efficiency [8]. Ensure full complementarity in the seed region (8-10 bases proximal to PAM) [8].

- Cellular environment factors: DNA repair pathway activity, chromatin state, and nuclear delivery efficiency can all impact observed editing outcomes [19].

Advanced PAM Identification and Characterization Methods

How can I identify functional PAM sequences for novel Cas proteins?

The PAM-DOSE (PAM Definition by Observable Sequence Excision) system provides a robust method for empirically determining functional PAM requirements directly in human cells [18]. This method uses a dual-fluorescence reporter system where successful CRISPR cleavage excises a tdTomato cassette, allowing EGFP expression [18].

Table 2: PAM-DOSE Experimental Workflow

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Library Construction | Clone randomized PAM library (e.g., NNNN) downstream of fixed target site in reporter plasmid [18] | Ensure complete randomization; verify library complexity |

| 2. Cell Transfection | Co-transfect reporter library with Cas nuclease and targeting gRNA expression vectors [18] | Include appropriate controls (empty vector, non-targeting gRNA) |

| 3. Fluorescence Screening | Isolate EGFP-positive cells via FACS 48-72 hours post-transfection [18] | Gate strictly for high EGFP, low tdTomato populations |

| 4. Sequence Analysis | Amplify and sequence integrated PAM regions from sorted cells via NGS [18] | Sequence sufficient reads for statistical power (≥10^5 recommended) |

| 5. Validation | Test individual high-frequency PAM sequences in validation assays [18] | Confirm functionality across multiple target sites |

The experimental workflow for PAM identification using this system follows this process:

What research reagent solutions are available for PAM studies?

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAM Characterization

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-Fluorescence Reporters | Empirical PAM identification in living cells [18] | PAM-DOSE system for determining functional PAM requirements |

| PAM Library Plasmids | Randomized PAM sequences for systematic screening [18] | High-throughput determination of PAM preferences |

| Multiple Cas Expression Vectors | Source of different Cas nucleases with varying PAM needs [16] | Comparison of PAM requirements across Cas proteins |

| Flow Cytometry | Quantification of editing efficiency via fluorescent markers [18] | Sorting successfully edited cells for downstream analysis |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Comprehensive analysis of PAM sequences from edited cells [18] | Identification of functional PAM enrichment patterns |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Engineered nucleases with altered PAM specificities [16] [8] | Targeting genomic regions inaccessible to wild-type Cas |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

How are AI and machine learning transforming PAM prediction and nuclease design?

Recent advances in artificial intelligence are revolutionizing CRISPR nuclease design, including PAM prediction and optimization:

- CRISPR-GPT: An AI tool that assists researchers in designing CRISPR experiments, including PAM-aware gRNA selection and troubleshooting [20]. The system uses 11 years of published CRISPR data to recommend optimal experimental designs [20].

- Protein Language Models: AI models trained on biological diversity can generate novel Cas proteins with customized properties, including PAM specificities [21]. These models have successfully created functional editors like OpenCRISPR-1 that diverge significantly from natural sequences [21].

- Off-Target Prediction: Advanced algorithms like CCLMoff use deep learning and RNA language models to predict off-target effects with improved accuracy, considering both gRNA sequence and PAM context [22].

What novel approaches address PAM limitations in advanced editing applications?

Prime editing with prolonged editing window (proPE) represents a significant advancement that partially alleviates PAM constraints for precise editing [19]. This system uses two distinct sgRNAs:

- Essential nicking guide RNA (engRNA): Conventional sgRNA that directs Cas9 to nick the target DNA [19]

- Template providing guide RNA (tpgRNA): Contains PBS and RTT sequences with truncated spacer that binds DNA without cleavage [19]

This separation of nicking and template functions extends the editing window and enhances efficiency for modifications beyond the typical PE range [19]. The proPE system demonstrates 6.2-fold increased editing efficiency for low-performing edits (<5% with standard PE) [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is the PAM sequence included in the guide RNA design?

No, the PAM sequence is not part of the guide RNA [16] [17]. When designing gRNAs for CRISPR experiments, researchers should only include the ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA [16]. The PAM must be present in the genomic DNA immediately downstream of the target site but is excluded from gRNA construction [16] [17].

Can I modify the PAM requirement of my Cas nuclease?

Yes, protein engineering approaches including directed evolution and structure-guided mutagenesis have successfully created Cas variants with altered PAM specificities [16] [8]. Examples include xCas9 and SpCas9-NG, which recognize NG instead of NGG PAMs [8]. However, these engineered variants often trade off some editing efficiency for PAM flexibility [19].

Why does my experiment fail even when a PAM is present?

PAM recognition is necessary but not always sufficient for efficient cleavage [16] [18]. Additional factors affecting efficiency include:

- Local chromatin accessibility and DNA methylation status [16]

- gRNA secondary structure that affects Cas9 binding [8]

- Specific nucleotide context around the PAM [18]

- Cellular delivery efficiency of CRISPR components [7]

- Competing DNA repair pathways in the target cells [8]

Are there truly "PAM-less" CRISPR systems available?

While no naturally occurring Cas nuclease is completely PAM-less, engineered variants like SpRY approach this ideal by recognizing extremely relaxed PAM sequences (NRN/NYN, where R is A/G and Y is C/T) [8]. Additionally, CRISPR-associated transposon (CAST) systems and some Cas14 variants show reduced or alternative PAM requirements [16]. However, these systems often come with trade-offs in editing efficiency or specificity [16] [19].

FAQs on Double-Stand Break and Repair

Q1: What are the primary DNA repair pathways that process Cas9-induced double-strand breaks, and how do they influence editing outcomes?

When Cas9 creates a double-strand break (DSB), the cell deploys several repair pathways, leading to different outcomes [23]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these pathways.

Table 1: Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Cas9 Editing

| Repair Pathway | Mechanism | Template Required? | Fidelity | Typical Editing Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Non-Homologous End Joining (cNHEJ) | Direct ligation of broken ends | No | Error-prone | Small insertions or deletions (indels); gene knockout [23] |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | Uses microhomologous sequences (5-25 bp) for alignment and repair | No | Error-prone | Larger deletions [23] [24] |

| Homologous Recombination (HR) | Uses a homologous DNA template (e.g., sister chromatid) for repair | Yes | High-fidelity | Precise edits; gene correction or knock-in [23] |

| Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) | Uses longer homologous repeats (>25 bp) flanking the break | No | Error-prone | Large deletions [23] |

The competition between these pathways determines the final result. For example, in dividing cells like iPSCs, MMEJ often dominates, creating larger deletions. In contrast, postmitotic cells like neurons rely more heavily on cNHEJ, resulting in a narrower distribution of small indels [24].

Q2: Why does my editing efficiency vary between different cell types, and how can I improve it?

Editing efficiency is highly dependent on cell type due to differences in cell state (dividing vs. nondividing), transfection efficiency, and innate DNA repair machinery [24].

- Dividing vs. Nondividing Cells: Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is largely restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, making it inefficient in nondividing cells [23] [24]. Furthermore, a 2025 study revealed that Cas9-induced indels accumulate much more slowly in postmitotic neurons and cardiomyocytes, taking up to two weeks to plateau, compared to just a few days in isogenic induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [24].

- Delivery Method: The choice of delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors, Virus-Like Particles (VLPs)) must be optimized for your specific cell type. For hard-to-transfect cells like neurons, VLPs have been shown to achieve up to 97% delivery efficiency [24].

- Strategies for Improvement:

- For Knockouts in Difficult Cells: Use an inducible Cas9 system. One study in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) achieved stable INDEL efficiencies of 82–93% for single-gene knockouts by optimizing parameters like nucleofection frequency and cell-to-sgRNA ratio [25].

- For Knock-ins in Non-Dividing Cells: Consider using base editors or prime editors, which can efficiently create precise single-base changes without requiring a DSB or an active HDR pathway [24].

- Chemical/Genetic Perturbation: Manipulating the DNA repair response with small molecules or by genetically knocking down specific repair factors can help direct repairs toward your desired outcome [24].

Q3: My sgRNA has high on-target scores in silico, but editing fails. What are common reasons for this, and how can I troubleshoot?

High computational scores don't guarantee success due to biological and experimental factors.

- Chromatin Inaccessibility: If the target DNA is tightly packed into heterochromatin, the Cas9-sgRNA complex may not be able to bind. Consider using chromatin-modifying agents or selecting target sites in open chromatin regions confirmed by ATAC-seq or similar assays [26] [27].

- Ineffective sgRNA: Some sgRNAs can induce high INDEL rates but fail to eliminate protein expression if the edits do not cause a frameshift or target a non-essential protein domain. A 2025 study identified an sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 that produced 80% INDELs but did not abolish ACE2 protein expression [25].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Protein Loss: Always confirm knockout experiments at the protein level (e.g., via Western blot) in addition to genomic sequencing [25].

- Check Cas9/sgRNA Expression: Confirm that both Cas9 and the sgRNA are being expressed at high enough levels in your cells [12].

- Use Multiple sgRNAs: Employing two or more sgRNAs against the same gene can dramatically increase the chance of a successful knockout [28].

- Validate with Synthetic sgRNA: If using plasmid-based sgRNA expression, try switching to chemically synthesized and modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA), which have enhanced stability and can reduce toxicity, potentially improving efficiency [25].

Q4: What is the difference between CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), and when should I use each?

CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPRi are distinct tools for different experimental goals.

- CRISPR-Cas9 (Nuclease-Active): This system uses a catalytically active Cas9 to create a DSB, leading to permanent changes in the DNA sequence via the repair pathways in Table 1. It is best for creating permanent gene knockouts [26] [27].

- CRISPRi (Interference): This system uses a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) that cannot cut DNA. The dCas9-sgRNA complex binds to the target site and acts as a steric block, physically preventing transcription by RNA polymerase. When fused to repressor domains like KRAB, it can robustly silence gene expression. The effect is reversible and does not alter the DNA sequence [26] [27] [29].

Table 2: CRISPR-Cas9 vs. CRISPRi Key Comparisons

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 (Knockout) | CRISPRi (Interference) |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Type | Catalytically active | Catalytically dead (dCas9) |

| DNA Break | Yes (Double-strand break) | No |

| Permanence | Permanent mutation | Reversible knockdown |

| Key Application | Complete loss-of-function studies | Studying essential genes; mimicking drug action; tunable knockdown [27] |

| Key Advantage | Permanent effect | Avoids DSB-related toxicity and off-target mutations [29] |

CRISPRi is particularly valuable for studying essential genes, as complete knockout would be lethal to the cell. It also better mimics the partial reduction of gene expression seen with many pharmaceutical treatments [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Low Knock-in (HDR) Efficiency

- Cause: HDR is a low-efficiency pathway that competes with the more dominant and error-prone NHEJ and MMEJ pathways, especially in non-dividing cells [23] [24].

- Solutions:

- Use NHEJ Inhibitors: Treat cells with small molecule inhibitors of key NHEJ proteins (e.g., DNA-PKcs inhibitor) to tilt the balance toward HDR [24].

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Since HDR is most active in S/G2 phases, synchronizing your cells or delivering CRISPR components during this window can boost HDR efficiency.

- Optimize Donor Template Design: For single-base edits, using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) as a donor template with symmetric homology arms can be effective. To prevent re-cleavage of the edited allele, design the edit to disrupt the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [25].

Problem: High Off-Target Activity

- Cause: The sgRNA may bind and cleave at genomic sites with sequences similar to the on-target site, especially if there are mismatches in the PAM-distal region [23].

- Solutions:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Engineered Cas9 proteins (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) have reduced off-target activity while maintaining strong on-target cleavage [12].

- Optimize sgRNA Design: Select sgRNAs with a minimal number of potential off-target sites. Use design tools that account for off-targets and avoid sgRNAs with seed regions that have many near-matches in the genome [26] [30] [28].

- RNP Delivery: Delivering preassembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex reduces the time the nucleus is exposed to active Cas9, which can lower off-target effects [24].

Problem: Cell Toxicity or Death

- Cause: High levels of DSBs can trigger p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Overexpression of Cas9 and prolonged nuclease activity can also be toxic [29].

- Solutions:

- Use CRISPRi: For gene silencing applications, switch to the DNA break-free CRISPRi system to avoid toxicity associated with DSBs [29].

- Titrate Component Amounts: Use the lowest effective concentration of Cas9 and sgRNA. Start with lower doses and titrate upwards to find a balance between editing and cell viability [12].

- Use Inducible Systems: A doxycycline-inducible Cas9 system allows for transient, controlled expression of Cas9, reducing long-term toxicity and improving editing efficiency in sensitive cells like hPSCs [25].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-KRAB | Catalytically dead Cas9 fused to the KRAB repressor domain. Provides robust transcriptional repression for CRISPRi [27]. | Reversible gene knockdown without altering DNA sequence. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9) with reduced off-target effects. | Experiments where specificity is critical, such as potential therapeutic applications [12]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered particles for delivering protein cargo (e.g., Cas9 RNP). Effective for hard-to-transfect cells [24]. | Delivering Cas9 RNP to postmitotic neurons with high efficiency (>95%) [24]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | sgRNAs synthesized with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate) to enhance stability [25]. | Increases sgRNA half-life, improving editing efficiency and reducing required dosage. |

| Inducible Cas9 System | Cas9 expression is controlled by an inducer (e.g., Doxycycline). Allows precise temporal control [25]. | Achieving high knockout efficiency in hPSCs while minimizing continuous Cas9 expression toxicity. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Small molecules that chemically inhibit key components of the classical NHEJ pathway. | Shifting repair balance toward HDR to improve knock-in efficiency [24]. |

Visualizing Key Concepts

Diagram 1: Competition Between DSB Repair Pathways

This diagram illustrates how a single Cas9-induced double-strand break can be processed by different cellular repair pathways, leading to a variety of mutational outcomes.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for High-Efficiency Knockout in hPSCs

This workflow outlines an optimized protocol for achieving high knockout efficiency in human pluripotent stem cells using an inducible Cas9 system, based on a 2025 study [25].

Strategic sgRNA Design: Practical Guidelines and Advanced Engineering for Enhanced Performance

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low On-Target Editing Efficiency

Q: My CRISPR experiment is showing very low rates of on-target editing. What target sequence factors should I investigate to improve this?

Low on-target efficiency often stems from suboptimal sgRNA sequence selection. The following factors are critical to troubleshoot:

Problem: The sgRNA spacer length is not optimal.

- Solution: Ensure your sgRNA spacer (the target-specific region) is within the 17-23 nucleotide range. [31] While a 20-nucleotide length is standard, [32] explored extensions up to 40 bp and 53 bp and found that for some target sites (PAM3), longer sgRNAs could improve specificity. However, for general use, a 20 bp spacer is recommended for SpCas9. [33]

Problem: The GC content of the sgRNA is outside the ideal range.

Problem: The target sequence is not unique in the genome.

Problem: The sgRNA sequence contains problematic nucleotide patterns.

- Solution: Avoid consecutive stretches of a single nucleotide (e.g., poly-T or poly-G tracts), as these can interfere with transcription and sgRNA stability. [31]

Experimental Protocol: Validating sgRNA On-Target Efficiency

- Design: Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPick, GenScript's tool) to select 3-5 candidate sgRNAs with high predicted on-target scores. [33] [34]

- Deliver: Transfert your cells with your chosen Cas9/sgRNA system (e.g., as a ribonucleoprotein complex or plasmid). [31]

- Harvest: Extract genomic DNA from the cells 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Analyze: Amplify the target region by PCR and quantify the indel frequency using T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) or TIDE assays, or by next-generation sequencing for the most accurate results. [31]

Guide 2: Mitigating High Off-Target Effects

Q: My sequencing data reveals unintended edits at off-target sites. How can I adjust my target sequence selection to improve specificity?

Off-target effects occur when the Cas9-sgRNA complex binds and cleaves DNA at sites similar to the intended target. To mitigate this:

Problem: The sgRNA has high homology to multiple genomic loci.

- Solution: Use off-target prediction algorithms (e.g., CFD score, MIT score) during the design phase. [34] Prioritize sgRNAs with a high off-target score, indicating low potential for off-target activity. [33] Tools like CRISOT use advanced molecular dynamics simulations to predict and optimize specificity. [35]

Problem: Mismatches in certain regions of the target sequence are tolerated.

- Solution: Be aware that mismatches between the sgRNA and DNA target in the "seed sequence" (the 8-12 nucleotides proximal to the PAM) are less tolerated and reduce off-target cleavage. In contrast, mismatches in the distal region are more easily tolerated. [8] Selecting a target with unique sequences in the seed region is crucial.

Problem: The standard 20 bp sgRNA is not specific enough for your target.

- Solution: Consider using truncated sgRNAs (shorter than 20 nt) or elongated sgRNAs (longer than 20 nt). Research has shown that extending sgRNA length can, in some cases, improve specificity for the target gene and reduce off-target DNA cleavage. [32]

Problem: The chosen Cas9 nuclease has relaxed specificity.

- Solution: Switch to a high-fidelity Cas9 variant, such as eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, or HypaCas9. [8] These engineered proteins have mutations that reduce off-target editing while maintaining robust on-target activity.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Genome-Wide Off-Target Effects

- Predict: Input your sgRNA sequence into an off-target prediction tool like CAS-OFFinder or the one integrated into CRISPOR to generate a list of potential off-target sites. [32] [34]

- Validate: Use targeted amplicon sequencing to deeply sequence the top predicted off-target sites (e.g., sites with ≤3 mismatches).

- Discover (Advanced): For a unbiased genome-wide profile, use methods like GUIDE-seq or Circle-seq. These techniques experimentally identify off-target sites by capturing double-strand breaks across the entire genome. [35]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the optimal length for an sgRNA target sequence for SpCas9? The optimal protospacer length for SpCas9 is 20 nucleotides immediately upstream of the PAM site. [33] While variations from 17-23 nt are used, a 20 nt length provides a standard balance of high activity and specificity. [31]

Q: How close does the target sequence need to be to the PAM site? The target sequence must be located immediately adjacent (5') to the PAM sequence. The Cas9 enzyme cuts approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM. [8] The PAM sequence itself (e.g., "NGG" for SpCas9) is not part of the sgRNA but must be present in the genomic DNA for recognition and cleavage. [33] [31]

Q: Does the position of the cut site within a gene affect the knockout efficiency? Yes. To maximize the probability of a gene knockout, design your sgRNA to target a region within the 5' front of the coding sequence (CDS) of the gene. [34] An edit here is more likely to cause frameshift mutations that lead to premature stop codons and a complete loss of function.

Q: What are the key sequence features of an ideal sgRNA? An ideal sgRNA has:

- A 20-nucleotide spacer sequence. [33]

- 40-60% GC content. [3] [31]

- A unique sequence with no homology to other genomic sites, especially with fewer than 3 mismatches. [34]

- No consecutive stretches of identical nucleotides (e.g., no poly-T tracts, which can terminate RNA Polymerase III transcription). [31]

Table 1: Impact of sgRNA Spacer Length on Cleavage Specificity (Based on in vitro assays)

| sgRNA Length (bp) | Impact on Native Template Cleavage | Impact on Off-target Cleavage | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 (Standard) | High efficiency | Variable, can be high | Good starting point for most experiments |

| 30 | Maintained high efficiency | Reduced for some PAM sites ( [32]) | Consider for targets with known off-target issues |

| 40 | Maintained high efficiency | Further reduced for some PAM sites ( [32]) | Useful for high-specificity requirements |

| 53 | Maintained high efficiency | Highest observed specificity at one PAM site ( [32]) | Specialist application for maximum specificity |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Optimal sgRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale & Consequences of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Spacer Length | 17-23 nt (20 nt standard) | Shorter: Reduced on-target efficiency. Longer: Can increase specificity but requires validation. [32] [31] |

| GC Content | 40% - 60% | Low GC: Unstable binding. High GC: sgRNA misfolding and increased off-target risk. [3] [31] |

| PAM Proximity | Immediately 5' to the PAM | The target sequence must be adjacent for Cas9 recognition. The PAM is not part of the sgRNA. [33] [8] |

| Seed Sequence | No mismatches | The 8-12 bases proximal to the PAM are critical; mismatches here greatly reduce cleavage. [8] |

Experimental Workflow and Optimization Logic

sgRNA Design and Validation Workflow

Strategies to Improve sgRNA Specificity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for sgRNA Design and Validation Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically synthesized, high-purity sgRNA; allows for chemical modifications to enhance stability. [3] | RNP delivery for rapid editing with minimal off-target effects. [31] |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA (IDT) | A synthetic, 100-nt RNA molecule combining crRNA and tracrRNA. [33] | Standardized, pre-designed sgRNAs for consistent experimental results. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) | Engineered Cas9 variants with mutations that reduce off-target editing. [8] | Experiments where specificity is critical, such as therapeutic development. |

| CRISOT Software Suite | Computational tool using RNA-DNA interaction fingerprints from MD simulations to predict and optimize sgRNA. [35] | Genome-wide off-target prediction and sgRNA optimization for improved specificity. |

| U6 Promoter Plasmids | Vectors for expressing sgRNA within cells; the U6 promoter ensures high transcription levels. [31] | Long-term expression of sgRNA for stable cell line generation. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Enzyme that detects and cleaves mismatched DNA in heteroduplexes. | Quick and cost-effective validation of indel formation at the target site. |

| Guide-it Screening Kit (Takara Bio) | A commercial kit for in vitro transcription and testing of sgRNA cleavage efficiency. [32] | Validating sgRNA function and RNP complex formation before cell experiments. |

The success of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing experiments hinges on the precise design of your single guide RNA (sgRNA). Among the critical design parameters, GC content—the percentage of nucleotides in the 20-nucleotide guide sequence that are either guanine (G) or cytosine (C)—stands out as a pivotal factor influencing both on-target efficiency and specificity. An optimal GC content, typically between 40% and 60%, facilitates stable binding between the sgRNA and its target DNA site without promoting excessive rigidity or off-target effects [36] [31]. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices to help you master GC content balance in your sgRNA designs, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of your CRISPR experiments.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common GC Content-Related Issues

This section addresses frequent problems, their underlying causes, and actionable solutions.

Problem: Consistently Low Editing Efficiency

- Symptoms: Low indel frequency, poor knockout efficiency despite confirmed delivery of CRISPR components.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- GC Content Too Low (<40%): Insufficient G-C bonds can lead to weak sgRNA-target DNA binding and unstable complex formation [31]. Redesign sgRNAs to include more G or C bases while staying within the optimal range.

- GC Content Too High (>80%): Excessively high GC can cause sgRNA rigidity, misfolding, and hinder Cas9 activation [36] [31]. It is also strongly correlated with highly stable secondary structures in the target DNA, making it inaccessible [37] [38]. Redesign sgRNAs to lower the GC content and use tools to predict target site accessibility.

Problem: High Rate of Off-Target Effects

- Symptoms: Unintended edits at genomic sites with sequence similarity to the target.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Suboptimal GC Content & Specificity: sgRNAs with very high GC content can tolerate mismatches better due to overly stable binding, increasing off-target potential [31]. Furthermore, low-specificity gRNAs can cause confounding effects like strong negative fitness effects even in non-essential genes [39]. Use advanced design software like GuideScan2 to analyze off-targets and ensure your sgRNA has high specificity in addition to optimal GC content [39].

Problem: Inefficient Editing in Polyploid Organisms

- Symptoms: Successful editing in one genomic copy but not in others (e.g., in hexaploid wheat).

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Lack of Specificity Across Genomes: In complex genomes, a high-quality sgRNA must be unique to the target gene and have minimal off-targets across all sub-genomes [40]. Use specialized tools like WheatCRISPR for polyploid crops and perform a comprehensive BLAST analysis against the entire pan-genome to ensure the designed sgRNA, with its specific GC content, targets all desired homologs uniquely [40] [41].

Problem: sgRNA Instability

- Symptoms: Rapid degradation of sgRNA, leading to low intracellular concentration and transient activity.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Inherent Instability of Linear RNA: Standard linear sgRNAs have a short half-life, which can limit editing efficiency, especially over time [42]. Consider using engineered circular guide RNAs (cgRNAs), which offer enhanced protection from exonuclease degradation and significantly higher stability and durability in cells, as demonstrated in Cas12f systems [42].

Essential Tools and Reagents for sgRNA Design and Validation

The table below lists key resources for implementing the protocols and strategies discussed in this guide.

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| GuideScan2 Software [39] | Genome-wide design and specificity analysis of gRNAs; identifies off-targets with high accuracy. |

| WheatCRISPR Software [40] [41] | Specialized tool for designing gRNAs in the complex, polyploid wheat genome. |

| Wheat PanGenome Database [40] [41] | Enables cultivar-specific gRNA design by providing genomic data across multiple wheat varieties. |

| U6 Promoter Plasmids [31] | A standard vector for high-level expression of sgRNA transcripts in mammalian cells. |

| Circular gRNA (cgRNA) Scaffold [42] | An engineered gRNA format with a covalently closed loop structure that confers high stability and prolonged activity. |

| Synthetic sgRNA with Chemical Modifications [31] | In vitro transcribed and chemically modified sgRNAs that enhance stability and reduce immune response. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating sgRNA Efficiency

A robust workflow for validating your designed sgRNAs is crucial. The diagram below outlines the key steps from design to final assessment.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Target Identification and sgRNA Design:

- Identify your target genomic region and the adjacent Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence appropriate for your Cas nuclease (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) [31].

- Using a design tool (e.g., GuideScan2, WheatCRISPR), generate a list of potential sgRNA sequences targeting your site of interest [39] [40].

- GC Content Check: Calculate and note the GC content for each candidate. Prioritize those falling within the 40-60% range [36] [31].

Specificity Analysis and Candidate Filtering:

- Input the candidate sgRNA sequences into a specificity analysis tool like GuideScan2. This software uses advanced algorithms to enumerate all potential off-target sites in the genome, accounting for mismatches [39].

- Filter your list to retain sgRNAs with high predicted on-target activity and a high specificity score (i.e., few or no predicted off-targets with high similarity) [39] [36].

Cloning and Delivery:

- Clone the final selected sgRNA sequence(s) into an appropriate expression vector, such as one containing the U6 promoter for high transcription levels in mammalian cells [31].

- Deliver the CRISPR components (Cas9 and sgRNA) into your target cells using your preferred method (e.g., plasmid transfection, Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, or viral vectors) [31].

Efficiency Assessment and Phenotypic Validation:

- Genotypic Analysis: 3-5 days post-delivery, harvest genomic DNA. Quantify editing efficiency (indel frequency) using next-generation sequencing (NGS), which provides the most accurate data, or alternative methods like the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay [31].

- Phenotypic Confirmation: If performing a knockout, confirm the loss of protein expression via Western blot or immunofluorescence. For knock-ins, validate correct integration via PCR and sequencing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is high GC content (>80%) detrimental, given that G-C bonds are stronger? A: While G-C bonds provide stability, an overabundance leads to several issues. First, it can cause the sgRNA itself to form stable, rigid secondary structures that may impede its proper binding to Cas9 or the target DNA [31]. Second, and more importantly, DNA regions with high GC content are more prone to form stable local secondary structures, making the target site less accessible for the Cas9-sgRNA complex to bind, thereby reducing cleavage efficiency [37] [38].

Q2: My sgRNA has a GC content of 45% but still performs poorly. What else should I check? A: GC content is one of several critical features. You should also investigate:

- Position-Specific Nucleotides: Certain nucleotides at specific positions are associated with higher efficiency (e.g., a G in position 20, an A in the middle of the sequence) or lower efficiency (e.g., a T in the PAM, poly-N sequences like GGGG) [36].

- Target Site Accessibility: Use RNA/DNA folding tools (e.g., ViennaRNA) to predict the secondary structure of your target genomic region. An inaccessible site, regardless of GC content, will hinder editing [37].

- sgRNA Secondary Structure: Check if the sgRNA itself is folding in a way that sequesters its seed region.

Q3: Are there new technologies to overcome the limitations of traditional sgRNAs? A: Yes, recent advances include the development of circular guide RNAs (cgRNAs). These are engineered to have a covalently closed loop structure, which makes them significantly more stable than linear sgRNAs because they are protected from exonuclease degradation. Studies show cgRNAs can enhance activation efficiency and increase the durability of editing effects over time [42].

Q4: How does GC content affect systems other than standard SpCas9? A: The principle of balancing stability and specificity via GC content is fundamental to nucleic acid hybridization and applies broadly. For instance, in RNAi (a technology that also uses a guide strand for target recognition), high siRNA GC-content negatively correlates with efficiency, primarily due to poor target site accessibility [37] [38]. When working with smaller Cas proteins like Cas12f, optimizing GC content and gRNA structure remains critical for achieving high activity [42]. Always consult literature and design tools specific to the nuclease you are using.

In CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) serves as the molecular GPS that directs the Cas9 nuclease to its specific DNA target. While the sequence of the sgRNA's spacer region determines target specificity, the structural architecture of the sgRNA itself profoundly influences editing efficiency. Research has demonstrated that two specific structural modifications—extending the duplex region and mutating poly-T tracts—can significantly enhance CRISPR-Cas9 performance. These optimizations address inherent limitations in the original sgRNA design, which featured a shortened duplex compared to the native bacterial crRNA-tracrRNA complex and contained a continuous sequence of thymines that can prematurely terminate transcription by RNA polymerase III. This technical guide explores the experimental evidence, implementation protocols, and troubleshooting strategies for maximizing CRISPR efficiency through sgRNA structural optimization.

▍Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why would extending the sgRNA duplex improve CRISPR knockout efficiency?

The original sgRNA design implemented for CRISPR-Cas9 systems features a shortened duplex region compared to the native crRNA-tracrRNA complex found in bacterial immune systems. Systematic investigation revealed that extending this duplex by approximately 5 base pairs significantly improves knockout efficiency, likely through enhanced complex stability. Research demonstrates that this extension increases gene knockout efficiency across multiple sgRNAs and cell types, with some targets showing dramatic improvements [43].

Q2: What is the functional consequence of the continuous TTTT sequence in sgRNAs?

The continuous sequence of thymines (TTTT) in conventional sgRNA designs acts as a pause signal for RNA polymerase III, potentially reducing transcription efficiency and subsequent sgRNA abundance. Mutational analysis has confirmed that disrupting this sequence, particularly at position 4 (where T→C or T→G substitutions prove most effective), significantly boosts knockout efficiency without compromising sgRNA functionality [43].

Q3: What specific structural modifications yield optimal editing efficiency?

The optimal sgRNA structure combines both duplex extension and poly-T tract mutation:

- Duplex extension: Adding approximately 5 bp to the duplex region

- Poly-T mutation: Changing the fourth thymine in the TTTT sequence to cytosine or guanine

This combined approach demonstrates significant, sometimes dramatic, improvements in knockout efficiency compared to the original structure across 15 of 16 tested sgRNAs [43]. The enhanced structure also dramatically improves the efficiency of challenging genome editing procedures such as gene deletion, with efficiency improvements of approximately 10-fold reported in multiple experiments [43].

Q4: How does optimized sgRNA structure benefit complex editing applications?

The efficiency gains from structural optimization prove particularly valuable for complex genome editing procedures that typically show low success rates with conventional sgRNAs. For gene deletion applications requiring dual cutting and fragment excision, optimized sgRNA structures increased efficiency from 1.6-6.3% to 17.7-55.9%, making such experiments practically feasible without requiring the screening of hundreds of colonies [43].

▍Quantitative Data on Structural Optimization

Table 1: Efficiency Improvements from Duplex Extension

| Duplex Extension Length | Knockout Efficiency Improvement | Optimal Context |

|---|---|---|

| +1 bp | Significant increase | Multiple sgRNAs |

| +3 bp | Significant increase | Multiple sgRNAs |

| +5 bp | Peak efficiency | Most sgRNAs |

| +8 bp | Increased but suboptimal | Some sgRNAs |

| +10 bp | Increased but suboptimal | Few sgRNAs |

Table 2: Poly-T Tract Mutation Efficiency Comparison

| Mutation Position | Mutation Type | Relative Efficiency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position 1 | T→C | High | Good alternative |

| Position 2 | T→C/G | Moderate | Secondary option |

| Position 3 | T→C/G | Moderate | Secondary option |

| Position 4 | T→C | Highest | Most effective |

| Position 4 | T→G | Very High | Excellent alternative |

| Position 4 | T→A | High | Less effective than C/G |

Table 3: Combined Optimization Impact on Different Applications

| Application Type | Original Efficiency | Optimized Efficiency | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCR5 gene knockout (sp1) | ~40% | ~65% | 1.6x |

| CCR5 gene knockout (sp10) | ~5% | ~55% | 11x |

| CCR5 gene knockout (sp14) | ~15% | ~65% | 4.3x |

| Gene deletion (Pair A) | 6.3% | 55.9% | ~8.9x |

| Gene deletion (Pair B) | 2.3% | 31.7% | ~13.8x |

| Gene deletion (Pair C) | 1.6% | 17.7% | ~11.1x |

▍Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing Optimized sgRNA Structures

Materials Needed:

- Target DNA sequence

- sgRNA design software (e.g., WheatCRISPR for plants [40])

- Molecular biology reagents for synthesis

Procedure:

- Identify target site: Select a 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to a PAM (NGG for SpCas9) using specialized software [40].

- Design extended duplex: Modify the standard sgRNA scaffold to extend the duplex region by 5 base pairs. The specific extension should complement the tracrRNA region.

- Mutate poly-T tract: Implement a T→C or T→G mutation at the fourth position of the continuous TTTT sequence in the sgRNA scaffold.

- Verify specificity: Conduct BLAST analysis against the relevant genome to ensure minimal off-target effects [44] [40].

- Validate structural stability: Use RNA structure prediction tools (e.g., RNAfold, RNAstructure) to calculate minimum free energy and ensure proper stem-loop formation [44].

Technical Notes:

- The beneficial effect of duplex extension typically peaks at approximately 5 bp, with 4 bp or 6 bp extensions showing similar efficiency in most cases [43].

- T→C mutations at position 4 sometimes show higher efficiency than T→G mutations for specific targets [43].

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Optimization Efficiency

Materials Needed:

- Cells (e.g., TZM-bl, Jurkat, or cell line relevant to your research)

- Plasmid constructs encoding Cas9 and sgRNAs

- Transfection reagents

- FACS analysis equipment or sequencing capabilities

Procedure:

- Clone sgRNA variants: Prepare both standard and optimized sgRNA constructs in appropriate expression vectors.

- Transfert cells: Deliver Cas9 and sgRNA constructs to target cells using appropriate methods (e.g., lipofection, electroporation).

- Quantify editing efficiency:

- For knockout experiments: Analyze protein disruption by FACS 72-96 hours post-transfection [43]

- For precise editing: Extract genomic DNA and perform deep sequencing of target loci

- Compare performance: Calculate the percentage of edited cells and compare efficiency between standard and optimized sgRNA designs.

- Evaluate statistical significance: Perform replicate experiments (n≥3) and use appropriate statistical tests to validate improvements.

▍Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for sgRNA Structural Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Design Tools | WheatCRISPR [40], CRISPRon [45] | Target selection, efficiency prediction, off-target assessment |

| Specificity Validation | BLAST [44] [40], Clustal Omega [44] [40] | Off-target analysis, sequence alignment |

| Structural Analysis | RNAstructure [44], RNAfold | Secondary structure prediction, stability assessment |

| Efficiency Prediction | DeepSpCas9 [45], Rule Set 2/3 [45] | AI-guided on-target activity forecasting |

| Validation Methods | Deep sequencing [43], FACS analysis [43] | Quantitative efficiency measurement |

▍Workflow Visualization

Optimization Workflow: This diagram illustrates the systematic approach to identifying common sgRNA efficiency problems and implementing structural solutions followed by comprehensive validation.

The strategic optimization of sgRNA structure through duplex extension and poly-T tract mutation represents a straightforward yet powerful method to enhance CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency. The experimental evidence demonstrates that these modifications can yield substantial improvements across diverse applications, from simple knockouts to complex gene deletions. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, integrating these structural optimizations with emerging advances such as prime editing [46] and artificial intelligence-guided design [45] will further accelerate the development of precise genome editing tools. The troubleshooting guidelines and experimental protocols provided here offer researchers a practical framework for implementing these enhancements in their own genome engineering workflows.

The success of CRISPR-based genome editing experiments hinges on the precise design of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs). Computational tools and algorithms for sgRNA design have become indispensable for researchers aiming to maximize on-target efficiency while minimizing off-target effects. This review synthesizes current sgRNA design platforms within the broader thesis that sophisticated computational design is fundamental to advancing genome editing research and therapeutic development. We provide a technical support framework to help scientists navigate common experimental challenges.

The selection of an sgRNA design algorithm can significantly impact screening outcomes. Benchmarking studies have evaluated these tools based on their performance in essentiality screens.

Table 1: Benchmark Comparison of Genome-wide sgRNA Libraries and Design Algorithms [47] [48]

| Library/Algorithm Name | Guides per Gene (Avg.) | Reported Performance in Essentiality Screens | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna (top3-VBC) | 3 | Strongest depletion of essential genes | Guides selected using Vienna Bioactivity (VBC) scores; performance matches or exceeds larger libraries. |

| MinLib-Cas9 (MinLib) | 2 | Strong average depletion of essential genes | Highly compact library; incomplete overlap in benchmark study. |

| Yusa v3 | 6 | Good performance | One of the better-performing pre-existing larger libraries. |

| Croatan | 10 | Good performance | Dual-targeting library; shows strong performance. |

| Brunello | 4 | Intermediate performance | Commonly used library. |

| Toronto v3 | 4 | Intermediate performance | Commonly used library. |

| Gecko V2 | 4 | Intermediate performance | Commonly used library. |

| Gattinara | 4 | Intermediate performance | - |

| Vienna (bottom3-VBC) | 3 | Weakest depletion of essential genes | Demonstrates importance of principled guide selection. |

A Standardized Experimental Protocol for sgRNA Design and Validation

Following a rigorous, multi-phase protocol is crucial for designing highly functional sgRNAs, especially for complex genomes. The workflow below outlines a comprehensive methodology adapted from established practices [40].

Diagram Title: sgRNA Design and Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodology [40]:

Gene Verification:

- Gene Identification: Select a promising target gene, preferably a known negative regulator for knock-out (SDN-1) studies. This identification should be based on an extensive review of literature, including prior genome editing, RNA interference (RNAi), or TILLING studies.

- Sequence and Location Retrieval: Use databases like Ensembl Plants and tools like KnetMiner to obtain the full gene sequence, chromosomal location, and identify all homologs.

- Conservation Analysis: Use Clustal Omega software to perform a multiple sequence alignment to assess the degree of similarity across the three wheat sub-genomes (A, B, D) and with genes in other species. This helps in designing gRNAs that target all desired homologs.

- Variant Checking: Consult the Wheat PanGenome database to check for presence-absence variations and structural variants across different cultivars, enabling cultivar-specific gRNA design.

gRNA Designing:

- Tool Selection: Use a species-appropriate design tool. For wheat, WheatCRISPR is tailored to handle its complex hexaploid genome [40]. For other systems, tools like CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP, or Benchling are widely used [49] [50].

- Parameter Setting: Select candidate gRNAs based on key parameters:

- GC Content: Ideal range is typically between 40% and 80%.

- Off-target Count: Use BLAST analysis against the entire genome to identify and minimize potential off-target sites.

- Target Location: Prioritize gRNAs that target exonic regions near the 5' end of the coding sequence or specific functional protein domains.

gRNA Analysis:

- Structural Validation: Predict and validate the gRNA's secondary structure and its Gibbs free energy. A stable structure with favorable energy is crucial for functionality.

- Self-complementarity Check: Analyze the gRNA sequence for any propensity to base pair within itself, which could lead to hairpin formation and impair its function.

- Vector Homology Check: Ensure the gRNA sequence has no significant similarity to the binary vector used for cloning, which could interfere with the experimental process.

The Rise of AI in Designing Genome Editors and sgRNAs

Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing the field by moving beyond the selection of sgRNAs to the de novo design of novel genome editors and highly functional guides.

AI-Generated Genome Editors: Large language models (LLMs) trained on vast biological datasets, such as the CRISPR–Cas Atlas (comprising over 1 million CRISPR operons), can now generate entirely new CRISPR-Cas proteins [51] [21]. These AI-designed editors, like OpenCRISPR-1, are highly divergent from any known natural sequence (∼57% identity to nearest natural Cas9) but remain functional in human cells, exhibiting comparable or improved activity and specificity [21]. This approach can expand the diversity of known Cas families by 4.8-fold, providing a vast new toolkit for editing [21].

AI for sgRNA Design: Machine learning models are critical for predicting sgRNA efficacy. Algorithms are trained on large-scale screening data to learn sequence features that correlate with high on-target activity. For example:

- VBC Scores: The Vienna Bioactivity (VBC) score is a genome-wide metric that effectively predicts sgRNA efficacy. Guides with high VBC scores show significantly stronger depletion of essential genes in knockout screens [47].

- Rule Set 3: This is another advanced scoring algorithm that correlates negatively with log-fold changes of guides targeting essential genes, indicating its predictive power for sgRNA efficiency [47].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function and Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| GMP-grade sgRNA | Ensures purity, safety, and efficacy for therapeutic applications. Critical for clinical trials. | Must be true GMP-grade, not "GMP-like"; timely procurement is a common challenge [52]. |

| Cas Nuclease (SpCas9, etc.) | The engine of the CRISPR system that performs the DNA cleavage. | Available as wild-type or high-fidelity (HiFi) variants; GMP-grade is required for clinical use [52]. |

| Base Editors (CBE, ABE) | Enables precise chemical conversion of a single DNA base without double-strand breaks. | Requires specialized gRNA design tools (e.g., BE-Designer, BE-Hive) [51] [50]. |

| Prime Editors (PE) | Allows for search-and-replace editing for small insertions, deletions, and all base-to-base conversions. | Newer systems like vPE demonstrate dramatically lower error rates [53]. |

| Delivery Vectors | Plasmids or viruses (AAV, Lentivirus) used to deliver CRISPR components into cells. | Choice affects efficiency, tropism, and persistence of edit; must be compatible with gRNA/Cas system size. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How do I choose between a single-targeting and a dual-targeting sgRNA library for my knockout screen?

- Answer: The choice depends on your specific needs for efficiency, library size, and sensitivity to DNA damage. Our benchmarking data shows that dual-targeting libraries (where two sgRNAs against the same gene are paired) can provide stronger depletion of essential genes and reduce false positives in resistance screens [47]. However, they also exhibit a modest fitness reduction even when targeting non-essential genes, potentially due to an heightened DNA damage response from creating two double-strand breaks [47]. For most applications where library size and cost are concerns, a minimal 3-guide-per-gene single-targeting library (e.g., selected using VBC scores) performs as well or better than larger historical libraries [47]. Reserve dual-targeting for cases where maximum knockout efficiency is critical and potential DNA damage response is not a primary concern.

FAQ 2: My sgRNAs are highly efficient in a diploid cell line but fail in a polyploid organism. What is the cause and solution?

- Answer: This is a common issue in polyploid crops like wheat, which has a large, repetitive genome with high sequence similarity between sub-genomes (A, B, and D) [40]. Failure is often due to the gRNA not being designed to account for all homologous copies (homeologs) or having excessive off-target sites.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Target Conservation: Use multiple sequence alignment (e.g., with Clustal Omega) to confirm your gRNA sequence is perfectly complementary to all target homeologs. Even a single mismatch can drastically reduce efficiency [40].

- Re-run Off-Target Prediction: Use a specialized tool like WheatCRISPR [40] or CRISPOR [49] to perform a BLAST search against the entire polyploid genome. This identifies potential off-target sites with higher fidelity.

- Check for Repetitive Regions: Avoid designing gRNAs in genomic areas with high repetitiveness. Target unique exonic sequences where possible.

- Consult Pan-Genome Databases: Use resources like the Wheat PanGenome database to check for cultivar-specific presence-absence variations that might explain editing failure in a particular strain [40].

FAQ 3: How can I control for off-target effects in my sensitive therapeutic application?

- Answer: Multiple strategies can be employed to enhance specificity:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Engineered Cas9 nucleases (e.g., eSpOT-ON, hfCas12Max) have stricter binding requirements, significantly reducing off-target cleavage [50].