Strategies for Managing False Positives in Screening Data: From Drug Discovery to Clinical Trials

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of false positives in scientific screening.

Strategies for Managing False Positives in Screening Data: From Drug Discovery to Clinical Trials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of false positives in scientific screening. It explores the foundational impact of false positives from high-throughput drug screening (HTS) to clinical trial data analysis, outlines advanced methodological approaches for mitigation, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and presents a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of screening methods. By synthesizing insights across the research pipeline, this resource aims to enhance data integrity, improve research efficiency, and accelerate the development of reliable therapeutic agents.

Understanding the Foundational Impact and Causes of False Positives in Research

A Researcher's Guide to Definitions and Impact

In screening data research, a false positive occurs when a test incorrectly indicates the presence of a specific condition or effect—such as a hit in a high-throughput screen—when it is not actually present. This is a Type I error, or a "false alarm" [1] [2]. Its counterpart, the false negative, occurs when a test fails to detect a condition that is truly present, incorrectly indicating its absence. This is a Type II error, meaning a real effect or "hit" was missed [1] [2].

The consequences of these errors are context-dependent and can significantly impact research validity and resource allocation. The table below summarizes these outcomes across different fields.

Table 1: Consequences of False Positives and False Negatives in Different Research Contexts

| Field/Context | Consequence of a False Positive | Consequence of a False Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Diagnosis [2] [3] | Unnecessary treatment, patient anxiety, and wasted resources. | Failure to treat a real disease, leading to worsened patient health. |

| Drug Development [4] | Pursuit of an ineffective treatment, wasting significant R&D budget and time. | Elimination of a potentially effective treatment, missing a healthcare and economic opportunity. |

| Spam Detection [3] [5] | A legitimate email is sent to the spam folder, potentially causing important information to be missed. | A spam email appears in the inbox, causing minor inconvenience. |

| Fraud Detection [3] | A legitimate transaction is blocked, causing customer inconvenience. | A fraudulent transaction is approved, leading to direct financial loss. |

| Scientific Discovery [6] [7] | Literature is polluted with false findings, inspiring fruitless research programs and ineffective policies. A field can lose its credibility [7]. | A true discovery is missed, delaying scientific progress and understanding. |

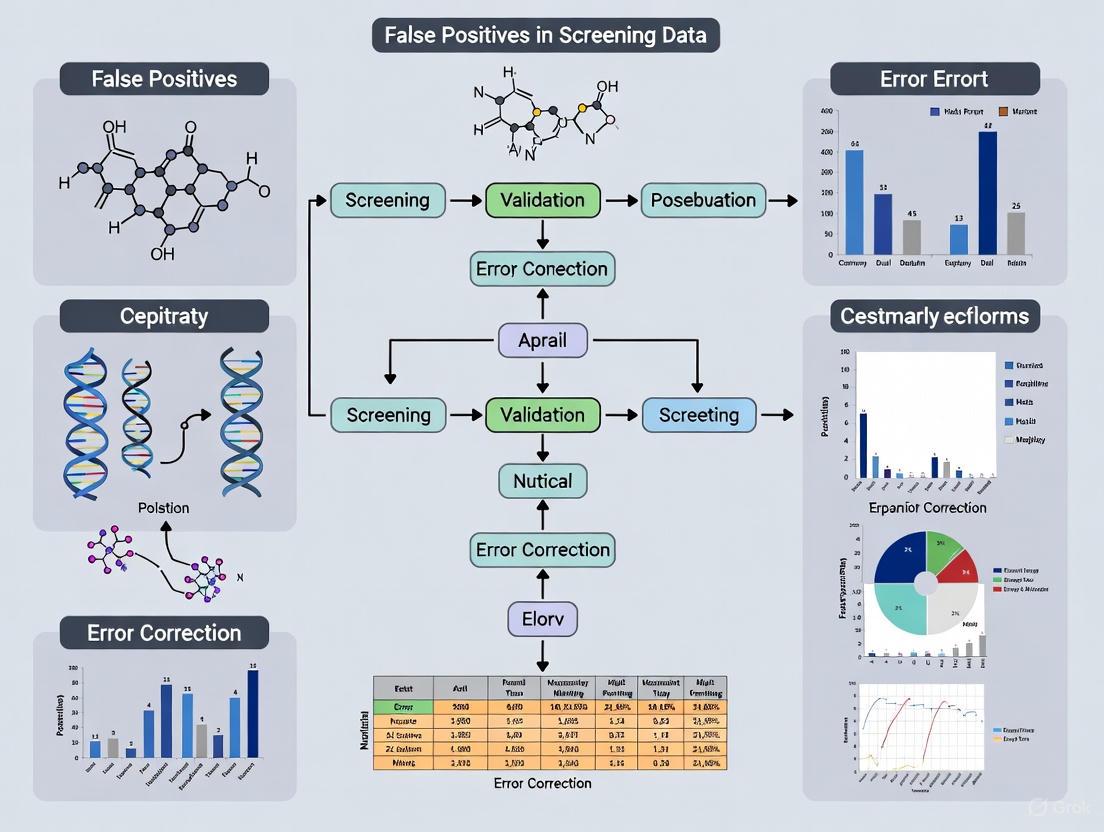

The following workflow illustrates the decision path in a binary test and where these errors occur.

Troubleshooting FAQs: Addressing False Positives and Negatives in the Lab

This section addresses common experimental challenges related to false positives and false negatives, offering practical solutions for researchers.

FAQ 1: My assay has no window at all. What should I check first? A complete lack of an assay window, where you cannot distinguish between positive and negative controls, often points to a fundamental setup issue [8].

- Primary Checks:

- Instrument Configuration: Verify that your microplate reader or other instrument is set up correctly. The most common reason for a TR-FRET assay to fail, for instance, is the use of incorrect emission filters. Always use the manufacturer-recommended filters for your specific instrument [8].

- Reagent Integrity: Check the expiration dates and storage conditions of all reagents. Improperly stored or old reagents may have degraded.

- Control Functionality: Ensure your positive and negative controls are working as expected. If controls are not behaving predictively, the problem may lie with the control preparations rather than the experimental samples.

FAQ 2: My assay window is small and noisy. How can I improve its robustness? A small or variable assay window increases the risk of both false positives and false negatives by making it difficult to reliably distinguish a true signal.

- Solution: Evaluate your assay using the Z'-factor, a statistical metric that assesses the quality and robustness of a high-throughput screen by considering both the dynamic range (the assay window) and the data variation [8].

- The formula is: Z' = 1 - [ (3σpositive + 3σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| ]

- Here, σ is the standard deviation and μ is the mean of the positive and negative controls.

- A Z'-factor > 0.5 is considered an excellent assay suitable for screening. A small window with high noise (large standard deviation) will yield a low Z'-factor, indicating the assay needs optimization before proceeding [8].

FAQ 3: Why are my IC₅₀/EC₅₀ values inconsistent between labs or experiments? Differences in calculated potency values like IC₅₀ often stem from variations in sample preparation rather than the assay itself [8].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Stock Solution Integrity: This is the primary reason for differences. Ensure the concentration, purity, and solvent composition of your compound stock solutions are accurate and consistent. Use freshly prepared stocks where possible [8].

- Protocol Adherence: Strictly standardize all procedural steps, including incubation times, temperatures, and reagent addition order.

- Data Normalization: Use ratiometric data analysis for assays like TR-FRET. Dividing the acceptor signal by the donor signal (e.g., 665 nm/615 nm for Europium) accounts for pipetting variances and minor lot-to-lot reagent variability, leading to more reproducible results [8].

FAQ 4: How can I reduce false positives in my statistical analysis? False positives in data analysis can arise from "researcher degrees of freedom"—undisclosed flexibility in how data is collected and analyzed [7].

- Corrective Measures:

- Pre-register Analysis Plans: Decide your data collection termination rule and primary analysis method before you begin collecting data [7].

- Report All Measures and Conditions: List all variables collected and all experimental conditions run, including any failed manipulations [7].

- Use Appropriate Power: Underpowered studies are a major source of unreliable results. Conduct power analysis to ensure your sample size is large enough to detect a true effect. One simulation in drug development showed that increasing Phase II trial power from 50% to 80% could increase productivity by over 60% by reducing false negatives [4].

Experimental Protocols for Error Mitigation

Protocol 1: Validating Assay Performance with Z'-Factor Calculation

This protocol provides a step-by-step method to quantitatively assess the robustness of a screening assay, helping to prevent both false positives and negatives caused by a poor assay system [8].

- Plate Setup: On a microplate, designate a minimum of 16 wells for the positive control and 16 wells for the negative control.

- Assay Execution: Run the assay according to your standard procedure on the entire plate.

- Data Collection: Measure the raw signal (e.g., RFU) for all control wells.

- Calculation:

- Calculate the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) for the positive control and the negative control.

- Apply the values to the Z'-factor formula: Z' = 1 - [ (3σpositive + 3σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| ]

- Interpretation:

- Z' ≥ 0.5: The assay is robust and suitable for screening.

- 0 < Z' < 0.5: The assay is marginal and may require optimization.

- Z' ≤ 0: The assay is not viable and cannot distinguish between controls.

Protocol 2: A Bayesian Framework for Interpreting "Significant" p-values

This methodological approach helps contextualize a statistically significant result to estimate the risk that it is a false positive, which is particularly high for novel or surprising findings [6].

- Define Prior Odds: Before the experiment, estimate the prior probability that your hypothesis is true, based on existing literature and scientific plausibility. For novel, paradigm-shifting hypotheses, this probability may be low [6].

- Conduct the Experiment: Perform your study and note the resulting p-value.

- Calculate the False Positive Risk (FPR): Use statistical methods (e.g., as proposed by Colquhoun, 2017) to calculate the probability that a significant finding is actually a false positive [1]. This FPR is always higher than the observed p-value.

- Interpretation: A p-value of 0.05 does not mean a 5% chance of a false positive. The actual risk could be much higher (e.g., 20-50%) depending on the prior odds. This framework emphasizes the need for replication and cautious interpretation of single studies, especially for novel findings published in high-impact journals [1] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in managing assay quality.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Quality Control

| Item/Reagent | Function in Managing False Positives/Negatives |

|---|---|

| TR-FRET Donor & Acceptor (e.g., Tb or Eu cryptate) | Forms the basis of a homogeneous, ratiometric assay. Using the recommended donor/acceptor pair with correct filters minimizes background noise and improves signal specificity, reducing error-prone signals [8]. |

| Validated Positive & Negative Controls | Critical for calculating the Z'-factor and validating every assay run. A well-characterized control set ensures the assay is functioning properly and can detect true effects. |

| Standardized Compound Libraries | Using compounds with verified purity and concentration in screening reduces false positives stemming from compound toxicity, aggregation, or degradation. |

| High-Quality Assay Plates | Optically clear, non-binding plates ensure consistent signal detection and prevent compound absorption, which can lead to inaccurate concentration-response data and both false positives and negatives. |

Visualization: The Precision-Recall Trade-Off

In machine learning and statistical classification, a key challenge is the inherent trade-off between false positives and false negatives, which is managed by adjusting the classification threshold. This relationship is captured by the metrics of precision and recall. The following diagram illustrates how changing the threshold to reduce one type of error inevitably increases the other.

In the high-stakes world of drug development, false positives represent a critical and costly challenge. A false positive occurs when an assay or screening method incorrectly identifies an inactive compound as a potential hit [9]. These misleading signals can derail research trajectories, consume invaluable resources, and ultimately skew the entire development pipeline. The impact cascades from early discovery through clinical trials, with studies indicating that a significant majority of phase III oncology clinical trials in the past decade have been negative for overall survival benefit, in part due to ineffective therapies advancing from earlier stages [10]. Understanding, quantifying, and mitigating false positives is therefore not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental requirement for research integrity and efficiency.

Quantifying the Impact: The Multifaceted Cost of False Positives

The cost of false positives extends far beyond simple reagent waste. It encompasses direct financial losses, massive time delays, and the opportunity cost of pursuing dead-end leads.

Financial and Resource Drain

False positives impose a significant financial burden on the drug development process, which already costs an estimated $1-2.5 billion and takes 10-15 years to bring a new drug to market [9]. The table below summarizes the key areas of impact.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of False Positives in Drug Development

| Area of Impact | Quantitative / Qualitative Effect | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Can derail entire HTS campaigns [11]. | A single HTS campaign can screen 250,000+ compounds. |

| Hit Rate Inflation | Artificially inflates hit rates, forcing re-screening and validation [11]. | Increases follow-up workload and costs. |

| Phase III Trial Failure | 87% of phase III oncology trials negative for OS benefit [10]. | Suggests many ineffective therapies advance to late-stage testing. |

| Clinical Trial False Positives | 58.4% false-positive OS rate when P=.05 is used [10]. | Based on analysis of 362 phase III superiority trials. |

The Ripple Effect on Workflow and Efficiency

The consequences of false positives create a ripple effect that impedes operational efficiency:

- Resource Misallocation: Teams spend weeks on secondary screening and validation of false leads, which can mean "hundreds of wasted follow-ups and delayed projects" [11].

- Distorted Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR): False positives can obscure genuine SAR, complicating the critical lead optimization process [11].

- Increased Attrition: The high failure rate of phase III trials, fueled in part by false advances from earlier stages, represents the ultimate resource drain, exposing patients to therapies with insufficient efficacy and consuming development costs that could have been allocated to more promising candidates [10].

Guide: Minimizing False Positives in ADP-Detection Assays

Problem: High false positive rates in assays measuring kinase, ATPase, or other ATP-dependent enzyme activity are skewing screening results and wasting resources.

Background: These assays are a universal readout for enzymes that consume ATP. Many traditional formats, particularly coupled enzyme assays, use secondary enzymes (like luciferase) to generate a signal. Test compounds can inhibit or interfere with these coupling enzymes rather than the target enzyme, producing a false-positive signal [11].

Solution: Implement a direct detection method.

- Step 1: Evaluate Your Current Assay Format. Compare your method against the following table to identify potential vulnerability to false positives.

Table 2: Comparison of ADP Detection Assay Formats and False Positive Sources

| Assay Type | Detection Mechanism | Typical Sources of False Positives |

|---|---|---|

| Coupled Enzyme Assays | Uses enzymes to convert ADP to ATP, driving a luminescent reaction. | Compounds that inhibit coupling enzymes, generate ATP-like signals, or quench luminescence. |

| Colorimetric (e.g., Malachite Green) | Detects inorganic phosphate released from ATP. | Compounds absorbing at the detection wavelength; interference from phosphate buffers. |

| Direct Fluorescent Immunoassays | Directly detects ADP via antibody-based tracer displacement. | Very low – direct detection of the product itself minimizes interference points. |

- Step 2: Transition to a Direct Detection Platform. Replace indirect, coupled assays with a direct method like the Transcreener ADP² Assay, which uses competitive immunodetection to measure ADP production without secondary enzymes [11].

- Step 3: Optimize Assay Parameters. Ensure the assay supports a wide ATP concentration range (e.g., 0.1 µM to 1 mM) to maintain physiological relevance and broad enzyme compatibility [11].

- Step 4: Validate with Controls. Use robust controls to confirm the assay's specificity, accuracy, precision, and limits of detection as part of a rigorous validation protocol [9].

The following workflow contrasts the problematic indirect method with the recommended direct detection approach:

Guide: Addressing False Positives in Mass Spectrometry-Based Screening

Problem: Even advanced, direct detection methods like mass spectrometry (MS) can be plagued by novel false-positive mechanisms that consume time and resources to resolve [12].

Background: MS is valued for its direct nature, which avoids common artifacts like fluorescence interference and eliminates the need for coupling enzymes. However, unexplained false positives still occur.

Solution: Develop a dedicated pipeline to identify and filter these specific false positives.

- Step 1: Acknowledge the Possibility. Recognize that no HTS method is completely immune to false positives, and investigate hits from MS screens with a critical eye.

- Step 2: Develop a Counter-Screen. Create a secondary assay designed specifically to test for the newly identified mechanism of interference. The nature of this counter-screen will depend on the specific false-positive mechanism discovered in your system [12].

- Step 3: Implement a Triaging Pipeline. Integrate this counter-screen into your primary screening workflow to automatically flag and eliminate these classes of false hits before they advance to more resource-intensive validation stages [12].

Key Reagents and Technologies for False Positive Mitigation

The following toolkit details essential solutions that can enhance the accuracy of your screening campaigns.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Minimizing False Positives

| Solution / Technology | Function | Key Benefit for False Positive Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Transcreener ADP² Assay | Direct, antibody-based immunodetection of ADP. | Eliminates coupling enzymes, a major source of compound interference [11]. |

| Microfluidic Devices & Biosensors | Creates controlled environments for cell-based assays and monitors analytes with high sensitivity. | Mimics physiological conditions for more relevant data; reduces assay variability [9]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers (e.g., I.DOT) | Provides precise, non-contact liquid dispensing for assay miniaturization and setup. | Enhances assay precision and consistency, minimizing human error and technical variability [9]. |

| AI & Machine Learning Platforms | Predictive modeling for hit identification and experimental design. | Accelerates hit ID and helps design assays that are less prone to interference [9]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | A systematic approach to optimizing assay parameters and conditions. | Reduces experimental variation and identifies robust assay conditions that improve signal-to-noise [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes of false positives in high-throughput drug screening? False positives typically arise from compound interference with the detection system. In coupled assays, this means inhibiting secondary enzymes like luciferase. Other common causes include optical interference (e.g., compound fluorescence or quenching), non-specific compound interactions with assay components, and aggregation-based artifacts [11] [9].

Q2: How can I convince my lab to invest in a new, more specific assay platform given budget constraints? Frame the decision in terms of total cost of ownership. While a direct detection assay might have a higher per-well reagent cost, it drastically reduces the false positive rate. This translates to significant savings by avoiding weeks of wasted labor on validating false leads, reducing reagent consumption for follow-up assays, and accelerating project timelines. One analysis showed that switching to a direct detection method could reduce false leads in a 250,000-compound screen from 3,750 to roughly 250—a 15x improvement [11].

Q3: Are there statistical approaches to reduce false positives in later-stage clinical trials? Yes. Research into phase III oncology trials has explored using more stringent statistical thresholds, such as lowering the P value from .05 to .005, which was shown to reduce the false-positive rate from 58.4% to 34.7%. However, this also increases the false-negative rate. A flexible, risk-based model is often recommended, where stringency is higher in crowded therapeutic areas and more relaxed in areas of high unmet need, like some orphan diseases [10].

Q4: We use mass spectrometry, which is a direct method. Why are we still seeing false positives? Mass spectrometry, while direct and less prone to common artifacts, is not infallible. Novel mechanisms for false positives that are unique to MS-based screening can and do occur. The solution is to develop a specific pipeline for detecting these unusual false positives, which may involve creating a custom counter-screen to identify and filter them out from your true hits [12].

Q5: How does assay validation help prevent false positives? A robust assay validation process is your first line of defense. By thoroughly testing and documenting an assay's specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness before it's used for screening, you can identify and correct vulnerabilities that lead to false positives. This includes testing for susceptibility to interference from common compound library artifacts [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is root cause analysis (RCA) in the context of screening data research? Root cause analysis is a systematic methodology used to identify the underlying, fundamental reason for a problem, rather than just addressing its symptoms. In screening data research, this is crucial for distinguishing true positive results from false positives, which can be caused by technical artifacts, data quality issues, or methodological errors. The goal is to implement corrective actions that prevent recurrence and improve data reliability [13].

2. Our team is new to RCA. What is a simple method we can use to start an investigation? The Five Whys technique is an excellent starting point. It involves repeatedly asking "why" (typically five times) to peel back layers of symptoms and reach a root cause. For example:

- Why was the assay result a potential false positive? Because the signal was anomalously high.

- Why was the signal anomalously high? Because the positive control was contaminated.

- Why was the positive control contaminated? Because the vial was used without proper aspiration technique.

- Why was the improper technique used? Because the training on the new liquid handler was incomplete.

- Why was the training incomplete? Because the training protocol was not updated to include the new equipment. The root cause is an outdated training protocol, not the individual user's mistake [13].

3. We are seeing a high rate of inconclusive results. How can we prioritize which potential cause to investigate first? A Pareto Chart is a powerful tool for prioritization. It visually represents the 80/20 rule, suggesting that 80% of problems often stem from 20% of the causes. By categorizing your inconclusive results (e.g., "low signal-to-noise," "precipitate formation," "edge effect," "pipetting error") and plotting their frequency, you can immediately identify the most significant category. Your team should then focus its RCA efforts on that top contributor first [13].

4. Our media fill simulations for an aseptic process are failing, but our investigation found no issues with our equipment or technique. What could be the source of contamination? As a documented case from the FDA highlights, the source may not be your process but your materials. In one instance, multiple media fill failures were traced to the culture media itself, which was contaminated with Acholeplasma laidlawii. This organism is small enough (0.2-0.3 microns) to pass through a standard 0.2-micron sterilizing filter. The resolution was to filter the media through a 0.1-micron filter or to use pre-sterilized, irradiated media [14].

5. How can we proactively identify potential failure points in a new screening assay before we run it? Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a proactive RCA tool. Your team brainstorms all potential things that could go wrong (failure modes) in the assay workflow. For each, you assess the Severity (S), Probability of Occurrence (O), and Probability of Detection (D) on a scale (e.g., 1-10). Multiplying S x O x D gives a Risk Priority Number (RPN). This quantitative data allows you to prioritize and address the highest-risk failure modes before they cause false positives or other data integrity issues [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Replicates and High Well-to-Well Variability

| Step | Action | Rationale & Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Liquid Handler Performance | Check calibration of pipettes, especially for small volumes. Ensure tips are seated properly and are compatible with the plates being used. Look for drips or splashes. |

| 2 | Inspect Reagent Homogeneity | Ensure all reagents, buffers, and cell suspensions are thoroughly mixed before dispensing. Vortex or pipette-mix as required. |

| 3 | Check for Edge Effects | Review plate maps for patterns related to plate location. Evaporation in edge wells can cause artifacts. Use a lid or a plate sealer, and consider using a humidified incubator. |

| 4 | Confirm Cell Health & Seeding Density | Use a viability stain to confirm cell health. Use a microscope to check for consistent monolayer or clumping. Re-count cells to ensure accurate seeding density across wells. |

| 5 | Analyze with a Fishbone Diagram | If the cause remains elusive, conduct a team brainstorming session using a Fishbone Diagram. Use the 6M categories (Methods, Machine, Manpower, Material, Measurement, Mother Nature) to identify all potential sources of variation [13]. |

Problem: Systematic False Positive Signals in a High-Throughput Screen

| Step | Action | Rationale & Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interrogate Compound/Reagent Integrity | Check for compound precipitation, which can cause light scattering or non-specific binding. Review chemical structures for known promiscuous motifs (e.g., pan-assay interference compounds, or PAINS). Confirm reagent stability and storage conditions. |

| 2 | Analyze Plate & Signal Patterns | Create a scatter plot of all well signals against their plate location. Look for systematic trends (e.g., gradients) indicating a temperature, dispense, or reader issue. Perform a Z'-factor analysis to reassay the robustness of the screen itself [13]. |

| 3 | Investigate Instrumentation | Check the spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or luminometer for calibration errors, dirty optics, or lamp degradation. Run system suitability tests with standard curves. |

| 4 | Employ Orthogonal Assays | Confirm any "hit" from a primary screen using a different, non-correlated assay technology (e.g., confirm a fluorescence readout with a luminescence or SPR-based assay). This helps rule out technology-specific artifacts. |

| 5 | Apply Fault Tree Analysis | For complex failures, use Fault Tree Analysis. This Boolean logic-based method helps model specific combinations of events (e.g., "Compound is fluorescent" AND "assay uses fluorescence polarization") that lead to the false positive outcome, helping to pinpoint the precise failure pathway [13]. |

Methodology and Data Visualization

Root Cause Analysis Methodologies for Research

The table below summarizes key RCA tools, their primary application, and a quantitative assessment of their ease of use and data requirements to help you select the right tool.

| Methodology | Primary Use Case | Ease of Use (1-5) | Data Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Five Whys | Simple, linear problems with human factors [13]. | 5 (Very Easy) | Low (Expert Knowledge) |

| Pareto Chart | Prioritizing multiple competing problems based on frequency [13]. | 4 (Easy) | High (Quantitative Data) |

| Fishbone Diagram | Brainstorming all potential causes in a structured way during a team session [13]. | 4 (Easy) | Medium (Team Input) |

| Fault Tree Analysis | Complex failures with multiple, simultaneous contributing factors; uses Boolean logic [13]. | 2 (Complex) | High (Quantitative & Logic) |

| Failure Mode & Effects Analysis (FMEA) | Proactively identifying and mitigating risks in a new process or assay [13]. | 3 (Moderate) | High (Structured Analysis) |

| Scatter Plot | Visually investigating a hypothesized cause-and-effect relationship between two variables [13]. | 3 (Moderate) | High (Paired Numerical Data) |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Five Whys Analysis

- Assemble a Team: Gather individuals with direct knowledge of the process and problem.

- Define the Problem: Write a clear, specific problem statement.

- Ask "Why?" Starting with the problem statement, ask why it happened.

- Record the Answer: Document the answer from the team's consensus.

- Iterate: Use the answer as the basis for the next "why?" Repeat this process until the team agrees the root cause is identified (this may be at the fifth why or a different number).

- Identify and Implement Countermeasures: Develop actions to address the root cause.

Logical Workflow for Root Cause Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying RCA methodologies to a data quality issue.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Screening & RCA |

|---|---|

| 0.1-micron Sterilizing Filter | Used to prepare media or solutions when contamination by small organisms like Acholeplasma laidlawii is suspected, as it can penetrate standard 0.2-micron filters [14]. |

| Z'-Factor Assay Controls | A statistical measure used to assess the robustness and quality of a high-throughput screen. It uses positive and negative controls to quantify the assay window and signal dynamic range, helping to identify assays prone to variability and false results. |

| Orthogonal Assay Reagents | A different assay technology (e.g., luminescence vs. fluorescence) used to confirm hits from a primary screen. This is critical for ruling out technology-specific artifacts that cause false positives. |

| Pan-Assay Interference Compound (PAINS) Filters | Computational or library filters used to identify compounds with chemical structures known to cause false positives through non-specific mechanisms in many assay types. |

| Stable Cell Lines with Reporter Genes | Engineered cells that provide a consistent and specific readout (e.g., luciferase, GFP) for a biological pathway, reducing variability and artifact noise compared to transiently transfected systems. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when handling missing data in clinical trials, with a focus on mitigating false-positive findings.

FAQ 1: Why can common methods like LOCF increase the risk of false-positive results? Answer: Simple single imputation methods, such as Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF), assume that a participant's outcome remains unchanged after dropping out (data are Missing Completely at Random). However, this assumption is often false. When data are actually Missing at Random (MAR) or Missing Not at Random (MNAR), these methods can create an artificial treatment effect, thereby inflating the false-positive rate (Type I error) [15] [16] [17]. Simulation studies have shown that LOCF and Baseline Observation Carried Forward (BOCF) can lead to an inflated rate of false-positive results (Regulatory Risk Error) compared to more advanced methods [15] [17].

FAQ 2: What are the most reliable primary analysis methods for controlling false positives? Answer: For the primary analysis, Mixed Models for Repeated Measures (MMRM) and Multiple Imputation (MI) are generally recommended over simpler methods [15] [16] [18]. These methods assume data are Missing at Random (MAR), which is a more plausible assumption than MCAR in many trial settings. They use all available data from participants and provide more robust control of false-positive rates [15] [17]. The table below summarizes the performance of different methods based on simulation studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Methods for Handling Missing Data

| Method | Key Assumption | Impact on False-Positive Rate | Key Simulation Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) | Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) | Can inflate false-positive rates [15] | Inflated Regulatory Risk Error in 8 of 32 simulated MNAR scenarios [15] |

| Baseline Observation Carried Forward (BOCF) | Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) | Can inflate false-positive rates [15] | Inflated Regulatory Risk Error in 12 of 32 simulated MNAR scenarios [15] |

| Multiple Imputation (MI) | Missing at Random (MAR) | Better controls false-positive rates [15] [18] | Inflated rate in 3 of 32 MNAR scenarios [15]; Low bias & high power for MAR [18] |

| Mixed Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) | Missing at Random (MAR) | Better controls false-positive rates [15] [18] | Inflated rate in 4 of 32 MNAR scenarios [15]; Least biased method in PRO simulation [18] |

| Pattern Mixture Models (PPM) | Missing Not at Random (MNAR) | Conservative for sensitivity analysis [18] | Superior for MNAR data; provides conservative estimate of treatment effect [18] |

FAQ 3: How should we handle missing data that is "Missing Not at Random" (MNAR)? Answer: For data suspected to be MNAR, where the reason for missingness is related to the unobserved outcome itself, sensitivity analyses are crucial. Control-based Pattern Mixture Models (PMMs), such as Jump-to-Reference (J2R) and Copy Reference (CR), are recommended [16] [18]. These methods provide a conservative estimate by assuming that participants who dropped out from the treatment group will have a similar response to those in the control group after dropout. This helps assess the robustness of the primary trial results under a "worst-case" MNAR scenario [18].

FAQ 4: What is the single most important step to reduce the impact of missing data? Answer: The most effective strategy is prevention during the trial design and conduct phase [19]. Proactive measures significantly reduce the amount and potential bias of missing data. Key tactics include:

- Implementing robust patient retention strategies [19] [16].

- Applying Quality-by-Design (QbD) principles to identify and mitigate risks to data quality early in the planning process [20].

- Using effective centralized monitoring tools, like well-designed Key Risk Indicators (KRIs), to detect site-level issues (e.g., rising dropout rates) early [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Multiple Imputation (MI) Analysis with Predictive Mean Matching

This protocol outlines the steps for using MI, a robust method for handling missing data under the MAR assumption, to reduce bias and control false-positive rates.

1. Imputation Phase:

- Objective: Create multiple complete datasets by replacing missing values with plausible estimates.

- Procedure:

a. Use a statistical procedure (e.g.,

PROC MIin SAS) to generatemcomplete datasets. Rubin's framework suggests 3-5 imputations, but more (e.g., 20-100) are common for better stability [16]. b. Specify an imputation model that includes the outcome variable, treatment group, time, baseline covariates, and any variables predictive of missingness. c. For continuous outcomes, use the Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) method. PMM imputes a missing value by sampling fromkobserved data points with the closest predicted values, preserving the original data distribution and reducing bias [16].

2. Analysis Phase:

- Objective: Analyze each of the

mimputed datasets separately. - Procedure:

a. Perform the planned primary analysis (e.g., ANCOVA model for the primary endpoint) on each of the

mcompleted datasets. b. From each analysis, save the parameter estimates (e.g., treatment effect) and their standard errors.

3. Pooling Phase:

- Objective: Combine the results from the

manalyses into a single set of estimates. - Procedure:

a. Calculate the final point estimate by averaging the

mtreatment effect estimates. b. Calculate the combined standard error using Rubin's Rules, which incorporates the average within-imputation variance (W) and the between-imputation variance (B) to account for the uncertainty of the imputations [16]. c. Use the combined estimates to calculate confidence intervals and p-values.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the entire MI process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key methodological "reagents" essential for designing and analyzing clinical trials with a low risk of false positives due to missing data.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Handling Missing Data

| Tool / Solution | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Mixed Models for Repeated Measures (MMRM) | A model-based analysis method that uses all available longitudinal data points under the MAR assumption without requiring imputation. It is often the preferred primary analysis for continuous endpoints [15] [18]. |

| Multiple Imputation (MI) Software (e.g., PROC MI) | A statistical procedure used to generate multiple plausible versions of a dataset with missing values imputed. It accounts for the uncertainty of the imputation process, leading to more valid statistical inferences [16]. |

| Pattern Mixture Models (PMMs) | A class of models used for sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of results under MNAR assumptions. Variants like "Jump-to-Reference" (J2R) are considered conservative and are valued by regulators [16] [18]. |

| Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) | Proactive monitoring tools (e.g., site-level dropout rates, data entry lag times) used during trial conduct to identify operational issues that could lead to problematic missing data, allowing for timely intervention [20]. |

| Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) | A pre-specified document that definitively states the primary method for handling missing data and the plan for sensitivity analyses. This prevents data-driven selection of methods and protects trial integrity [16] [21]. |

Advanced Methodologies to Minimize False Positives in Data Screening

Understanding LOCF, BOCF, and False Positives

In drug development, the primary analysis often relies on specific methods to handle missing data. Two traditional approaches are Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) and Baseline Observation Carried Forward (BOCF). These methods work by substituting missing values; LOCF replaces missing data with a subject's last available measurement, while BOCF uses the baseline value.

A false positive in this context occurs when a study incorrectly concludes that a drug is more effective than the control, when in reality it is not. This is also known as a Regulatory Risk Error (RRE). The core of the problem is that LOCF and BOCF are based on a restrictive assumption that data are Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) [15].

Modern methods like Multiple Imputation (MI) and Likelihood-based Repeated Measures (MMRM) are less restrictive, as they assume data are Missing at Random (MAR). When data are actually Missing Not at Random (MNAR), the use of LOCF and BOCF can inflate the rate of false positives, increasing regulatory risks compared to MI and MMRM [15].

The table below summarizes a simulation study comparing the false-positive rates of these methods [15].

| Method | Underlying Assumption | Scenarios with Inflated False-Positive Rates (out of 32) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOCF | Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) | 12 | Inflates regulatory risk; no scenario provided adequate control where modern methods failed. |

| LOCF | Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) | 8 | Inflates regulatory risk; no scenario provided adequate control where modern methods failed. |

| Multiple Imputation (MI) | Missing at Random (MAR) | 3 | Better choice for primary analysis; superior control of false positives. |

| MMRM | Missing at Random (MAR) | 4 | Better choice for primary analysis; superior control of false positives. |

A Practical Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

To empirically validate the performance of different methods for handling missing data, you can implement the following experimental workflow. This protocol is based on simulation studies that have identified the shortcomings of legacy methods [15].

Objective: To compare the rate of false-positive results (Regulatory Risk Error) generated by BOCF, LOCF, MI, and MMRM under a controlled Missing Not at Random (MNAR) condition.

Materials & Software: Statistical software (e.g., R, SAS, Python), predefined clinical trial simulation model.

Procedure:

- Dataset Generation: Simulate a complete, primary clinical trial dataset for a drug versus control study. The true treatment effect should be defined as zero to allow for false-positive detection [15].

- Induce Missing Data: Systematically remove a portion of the post-baseline data from the simulated dataset using an MNAR mechanism. This means the probability of data being missing is related to the unobserved outcome itself [15].

- Apply Methods: Analyze the resulting incomplete dataset using four different methods:

- Baseline Observation Carried Forward (BOCF)

- Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF)

- Multiple Imputation (MI)

- Mixed-Model Repeated Measures (MMRM)

- Record Outcome: For each method, record the statistical conclusion regarding the drug's efficacy. A false positive is recorded if the method incorrectly indicates a statistically significant benefit for the drug (p < 0.05).

- Replicate and Calculate: Repeat steps 1-4 a large number of times (e.g., 10,000 iterations) for the same MNAR scenario. The false-positive rate (RRE) for each method is calculated as the percentage of iterations that yielded a false positive.

- Compare: Compare the calculated RRE of BOCF and LOCF against the RRE of MI and MMRM. An inflated RRE indicates a higher risk of false positives.

Expected Outcome: This experiment will typically show that BOCF and LOCF produce a higher false-positive rate (RRE) compared to MI and MMRM when data are missing not at random [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

When designing experiments and analyzing data to mitigate false positives, having the right "reagents" — whether computational or statistical — is crucial. The following table details key solutions for your research.

| Tool / Method | Type | Primary Function | Role in Addressing False Positives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Imputation (MI) | Statistical Method | Handles missing data by creating several complete datasets and pooling results. | Reduces bias from missing data; less likely than LOCF/BOCF to inflate false positives under MAR/MNAR [15]. |

| Mixed-Model Repeated Measures (MMRM) | Statistical Model | Analyzes longitudinal data with correlated measurements without imputing missing values. | Provides a robust, likelihood-based approach that better controls false-positive rates [15]. |

| Risk-Based Quality Management (RBQM) | Framework | Shifts focus from 100% data verification to centralized monitoring of critical data points. | Improves overall data quality and enables proactive issue detection, indirectly reducing factors that contribute to spurious findings [22]. |

| Homogenous Time Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) | Assay Technology | A biochemical assay used to study molecular interactions. | Includes built-in counter-screens (e.g., time-zero addition, dual-wavelength assessment) to identify compound interference, a common source of false hits in screening [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why do LOCF and BOCF remain popular if they inflate false-positive rates? There is a persistent perception that the inherent bias in LOCF and BOCF is conservative and protects against falsely claiming a drug is effective. However, simulation studies have proven this false. These methods can create an illusion of stability and inflate the apparent effect size, leading to a higher chance of a false positive claim of efficacy [15].

2. What is the key difference between the MCAR and MAR assumptions? MCAR (Missing Completely at Random): The probability that data is missing is unrelated to both the observed and unobserved data. It is a completely random event. This is the unrealistic assumption underlying LOCF and BOCF. MAR (Missing at Random): The probability that data is missing may depend on observed data (e.g., a subject with worse baseline symptoms may be more likely to drop out), but not on the unobserved data. This is the more plausible assumption for MI and MMRM [15].

3. My clinical trial has a low rate of missing data. Is it safe to use LOCF? No. Even with a low amount of missing data, using an inappropriate method can bias the results. The risk is not solely about the quantity of missing data, but about the nature of the missingness mechanism. Modern methods like MMRM are superior even with small amounts of missing data and should be considered the primary analysis for regulatory submission [15].

4. Beyond false positives, what other risks do legacy methods pose? Using legacy methods can lead to inefficient use of resources. Furthermore, as the industry moves towards risk-based approaches and clinical data science, reliance on outdated methods like LOCF and BOCF can hinder innovation, slow down database locks, and ultimately delay a drug's time to market [22].

5. Our team is familiar with LOCF. How can we transition to modern methods? Transitioning requires both a shift in mindset and skill development. Start by:

- Education: Discuss published comparative studies (like the one cited here) with your team.

- Upskilling: Invest in training for statisticians and data scientists on MI and MMRM implementation.

- Pilot Testing: Apply modern methods in parallel with legacy methods on completed studies to build internal comfort and demonstrate their impact.

- Consultation: Engage with regulatory statisticians early to gain alignment on using MI or MMRM as the pre-specified primary analysis [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

MMRM Convergence Issues

Problem: My Mixed Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) fails to converge or produces unreliable estimates.

Solution:

- Check Covariance Structure: Ensure you've selected an appropriate covariance structure (unstructured, compound symmetry, autoregressive). Unstructured covariance is most flexible but requires more parameters. Start with simpler structures if you have convergence issues. [24]

- Verify Time-by-Covariate Interactions: Always include time-by-covariate interactions in your MMRM specification. Omitting these interactions can reduce power and robustness against dropout bias. [25]

- Inspect Starting Values: Poor starting values can prevent convergence. Use method of moments estimates or simplified model results as starting values.

- Increase Iterations: For complex models with many parameters, increase the maximum number of iterations in your estimation algorithm.

Multiple Imputation Compatibility Problems

Problem: After using multiple imputation, my analysis results seem inconsistent or implausible.

Solution:

- Check Imputation Level Strategy: For multi-item instruments, decide whether to impute at the item-level or score-level. Empirical evidence shows item-level imputation may yield different results than score-level imputation. [26]

- Verify Included Variables: Include all analysis variables in the imputation model, including outcome and auxiliary variables that may predict missingness. Omission can introduce bias. [27]

- Assess Imputation Number: Use sufficient number of imputations. While 3-5 was historically common, modern recommendations suggest 20-100 imputations depending on the percentage of missing data. [28]

- Examine Pooling Results: Ensure proper pooling of estimates using Rubin's rules. Software should automatically combine parameter estimates and standard errors across imputed datasets. [16]

False Positive Control in Screening Data

Problem: My screening data analysis produces unexpectedly high false positive rates.

Solution:

- Adjust for Multiple Comparisons: When running multiple statistical tests, implement correction methods like Bonferroni or Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate control. Uncorrected testing dramatically increases false positives. [29]

- Validate Missing Data Mechanisms: Conduct sensitivity analyses to test whether missingness mechanisms (MCAR, MAR, MNAR) affect your conclusions. [26]

- Power Analysis: Conduct power analysis before data collection to ensure adequate sample size. Underpowered studies increase both false positive and false negative rates. [30]

Table 1: Comparison of Missing Data Handling Methods in Clinical Trials

| Method | Bias Risk | Handling of Uncertainty | Regulatory Acceptance | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Case Analysis | High | Poor | Low | Minimal missingness (<5%) MCAR only |

| Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) | High | Poor | Decreasing | Historical comparisons only |

| Single Imputation | Medium | Poor | Low | Not recommended for primary analysis |

| Multiple Imputation | Low | Good | High | Primary analysis with missing data |

| MMRM | Low to Medium | Good | High | Repeated measures with monotone missingness |

Frequently Asked Questions

MMRM Implementation Questions

Q: When should I choose MMRM versus multiple imputation for handling missing data in longitudinal studies?

A: The choice depends on your data structure and research question:

- Use MMRM when you have longitudinal data with monotone missingness patterns (dropouts) and complete baseline covariates. MMRM uses all available data without explicit imputation. [26]

- Use multiple imputation when you have intermittent missingness, missing baseline covariates, or more than two timepoints. [26]

- For clinical trials with repeated measures, MMRM is often the preferred primary analysis method. [16]

Q: How do I specify time-by-covariate interactions in MMRM correctly?

A: Always include interactions between time and baseline covariates in your MMRM model. For example, in R's mmrm package: [25]

Omitting these interactions can eliminate the power advantage of MMRM over complete-case ANCOVA. [25]

Multiple Implementation Questions

Q: Should I impute at the item level or scale score level for multi-item questionnaires?

A: Impute at the item level rather than the composite score level. Empirical studies comparing EQ-5D-5L data found that mixed models after multiple imputation of items yielded different (typically lower) scores at follow-up compared to score-level imputation. [26]

Q: How many imputations are sufficient for my study?

A: While traditional rules suggested 3-5 imputations, modern recommendations are higher:

- Start with at least 20 imputations

- For higher percentages of missing data (>30%), use 40-100 imputations

- The number should be at least equal to the percentage of incomplete cases [27] [28]

False Positive Concerns

Q: How can I minimize false positives when analyzing screening data with multiple endpoints?

A: Implement a hierarchical testing strategy:

- Pre-specify primary, secondary, and exploratory endpoints

- Use gatekeeping procedures for multiple families of endpoints

- Apply False Discovery Rate (FDR) control within endpoint families

- Consider Bayesian approaches for false positive control [30] [29]

Q: Does handling missing data affect false positive rates?

A: Yes, inadequate handling of missing data can inflate false positive rates. Complete case analysis and single imputation methods can:

- Introduce selection bias

- Produce artificially narrow confidence intervals

- Increase both type I and type II error rates [16]

Table 2: Impact of Statistical Decisions on Error Rates

| Statistical Decision | Impact on False Positives | Impact on False Negatives | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| No multiple testing correction | Dramatically increases | Variable | Always correct for multiple comparisons |

| Complete case analysis with >5% missingness | Increases | Increases | Use MMRM or MI |

| Underpowered study (<80% power) | Variable | Increases | Conduct power analysis pre-study |

| Inappropriate covariance structure | Variable | Increases | Use unstructured when feasible |

Workflow Diagrams

Multiple Imputation Workflow

Multiple Imputation Process Flow

MMRM Implementation Checklist

MMRM Implementation Steps

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for MMRM and Multiple Imputation

| Tool Name | Function | Implementation Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmrm R Package | Fits MMRM models | Uses Template Model Builder for fast convergence; supports various covariance structures | [24] |

| mice R Package | Multiple imputation using chained equations | Flexible for different variable types; includes diagnostic tools | [31] |

| PROC MIXED (SAS) | MMRM implementation | Industry standard for clinical trials; comprehensive covariance structures | [16] |

| PROC MI (SAS) | Multiple imputation | Well-documented for clinical research; integrates with analysis procedures | [16] |

| brms.mmrm R Package | Bayesian MMRM | Uses Stan backend; good for complex random effects structures | [32] |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Bayesian MMRM Validation

When implementing Bayesian MMRM using packages like {brms}, validation is crucial:

- Use simulation-based calibration to check implementation correctness

- Be aware that complex models with treatment groups and unstructured covariance may have identification issues

- Prior specification strongly influences results, particularly for covariance parameters [32]

Multilevel Multiple Imputation

For clustered or multilevel data (patients within hospitals, students within schools):

- Use multilevel imputation models that account for the data structure

- Specify random effects appropriately in the imputation model

- For longitudinal data, restructure from wide to long format before imputation [31]

Sensitivity Analyses

Always conduct sensitivity analyses for missing data assumptions:

- Compare results under different missingness mechanisms (MAR vs MNAR)

- Use pattern-mixture models or selection models to assess robustness

- Document all assumptions about missing data in your statistical analysis plan [26] [16]

Leveraging Entity Resolution and Advanced Analytics for Improved Match Precision

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common data quality issues that cause false positives in entity resolution for research data?

False positives often originate from data quality issues and inappropriate matching thresholds. Common causes include:

- Identifier Problems: Unique IDs that are null, missing, repeated, or not unique within or across data sources can cause erroneous matches [33].

- Inconsistent Formats: The same entity may appear with different formatting across systems (e.g., "Jane Smith" vs. "Smith, Jane"), leading matching algorithms to treat them as distinct entities [34] [35].

- Ambiguous Entity Information: Some records may look similar but refer to different entities (e.g., two people with the same name and birthdate), creating uncertainty that simple rules cannot resolve [34].

Q2: How can I reduce the manual review workload in my entity resolution process without compromising accuracy?

Implementing a dual-threshold approach with optimization can significantly reduce manual review. Research has shown that by using particle swarm optimization to tune algorithm parameters, the manual review size can be reduced from 11.6% to 2.5% for deterministic algorithms and from 10.5% to 3.5% for probabilistic algorithms, while maintaining high precision [36]. Furthermore, employing active learning strategies, where only the most informative record pairs are sampled for labeling, can achieve comparable optimization results with a training set of 3,000 records instead of 10,000 [36].

Q3: What is the difference between rule-based and ML-powered matching, and when should I use each?

- Rule-Based Matching: Uses a set of customizable, predefined rules (e.g., exact matching, fuzzy matching) to find matches. It is reliable when unique identifiers are present and offers high transparency [37] [34]. However, it can be brittle with messy or incomplete data.

- ML-Powered Matching: Uses a machine learning model that analyzes patterns holistically across all record fields. It is more powerful for accounting for errors, missing information, and subtle similarities that rule-based systems might miss. It provides a confidence score for each match, helping to rank accuracy [37]. ML-based matching is often preferable for complex, noisy data where deterministic rules are insufficient.

Q4: Our research data is fragmented across multiple siloed systems. How can we integrate it for effective entity resolution?

A robust data preparation stage is critical. This involves:

- Standardization: Converting data into consistent formats (e.g., date formats, phone numbers).

- Normalization: Text normalization to handle typos and inconsistencies [34].

- Enrichment: Augmenting records with reliable reference data to improve match quality [35]. Building or buying unified data platforms that can consolidate these fragmented sources is a key step before matching can begin [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Rate of False Positives in Matching Results

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly permissive matching rules or low confidence thresholds. | Review the rules and confidence scores of the false positive pairs. Analyze which fields contributed to the match. | Adjust matching rules to be more strict. For ML-based matching, increase the confidence score threshold required for an automatic match [37]. |

| Poor data quality in key identifier fields. | Profile data to check for nulls, inconsistencies, and formatting variations in fields used for matching (e.g., SSN, names) [35]. | Implement or enhance data cleaning and standardization pipelines before the matching process [34]. |

| Lack of a manual review process for ambiguous cases. | Check if your workflow has a "potential match" or "indeterminate" category for records that fall between match/non-match thresholds [36]. | Implement a dual-threshold system that classifies results into definite matches, definite non-matches, and a set for manual review. This prevents automatic, potentially incorrect, classifications [36]. |

Issue: Entity Resolution Job Fails or Produces Error Files

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Invalid Unique IDs in the source data. | Check the error log or file generated by the service. Look for entries related to the Unique ID [33]. | Ensure the Unique ID field is present in every row, is unique across the dataset, and does not exceed character limits (e.g., 38 characters for some systems) [33]. |

| Use of reserved field names in the schema. | Review the schema mapping for field names like MatchID, Source, or ConfidenceLevel [33]. |

Create a new schema mapping, renaming any fields that conflict with reserved names used by the entity resolution service [33]. |

| Internal server error. | Check if the error message indicates an internal service failure [39]. | If the error is due to an internal server error, you are typically not charged, and you can retry the job. For persistent issues, contact technical support [33]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Optimizing a Dual-Threshold Entity Resolution System

This methodology is based on a published study that successfully reduced manual review while maintaining zero false classifications [36].

1. Objective: To tune the parameters of entity resolution algorithms (Deterministic, Probabilistic, Fuzzy Inference Engine) to minimize the size of a manual review set, under the constraint of no false classifications (PPV=NPV=1) [36].

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Data Source: Clinical data warehouse or similar research database with known duplicate records.

- Algorithms: Simple Deterministic, Probabilistic (Expectation-Maximization), Fuzzy Inference Engine (FIE).

- Optimization Framework: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) or a similar computational optimization technique.

- Computing Environment: Sufficient processing power for iterative model training and evaluation.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Standardize and clean the data. Remove stop-words and punctuation. Standardize names using a lookup table and validate critical fields like Social Security Numbers [36].

- Step 2: Blocking. Apply a blocking procedure (e.g., matching on first name + last name, last name + date of birth) to limit the search space to potential duplicate record pairs [36].

- Step 3: Generate Gold Standard Data. Randomly select a large set of record-pairs (e.g., 20,000). Have these reviewed by multiple experts in a stepwise process to establish a definitive match/non-match status for each pair. Split this into a training set (e.g., 10,000 pairs) and a held-out test set (e.g., 10,000 pairs) [36].

- Step 4: Define Algorithm and Baselines. Select the algorithms to optimize. Define a baseline set of parameters for each based on literature or preliminary experimentation [36].

- Step 5: Optimize Parameters. Run the optimization process (e.g., PSO) on the training set. The objective function should seek to minimize the number of record-pairs classified into the "manual review" category, while ensuring no pairs are misclassified [36].

- Step 6: Evaluate. Apply the optimized algorithms to the held-out test set. Measure the size of the manual review set and the classification accuracy.

4. Quantitative Data Summary:

| Algorithm | Baseline Manual Review | Optimized Manual Review | Precision after Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Deterministic | 11.6% | 2.5% | 1.0 |

| Fuzzy Inference Engine (FIE) | 49.6% | 1.9% | 1.0 |

| Probabilistic (EM) | 10.5% | 3.5% | 1.0 |

Data derived from training on 10,000 record-pairs using particle swarm optimization [36].

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Efficient Training Set Labeling

1. Objective: To reduce the size of the required training set for entity resolution algorithm optimization by strategically sampling the most informative record pairs.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Start with a small, random sample of record-pairs (e.g., 2,000) from the total training pool.

- Step 2: Have an expert label these pairs with match/non-match status.

- Step 3: Run a preliminary optimization on this small set.

- Step 4: Use a marginal uncertainty sampling strategy. Apply the current model to the entire unlabeled pool and select a small batch of additional records (e.g., 25 pairs) that are closest to the match/non-match thresholds [36].

- Step 5: Get expert labels for this new, informative batch.

- Step 6: Retrain/optimize the model with the enlarged training set.

- Step 7: Repeat steps 4-6 for a set number of iterations or until performance plateaus. The cited study achieved high performance with a total of 3,000 records using this method, compared to 10,000 with random sampling [36].

Workflow Visualization

Entity Resolution Workflow

Dual-Threshold Decision Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A computational method for iteratively optimizing algorithm parameters to find a minimum or maximum of a function. Used to tune matching thresholds to minimize manual review [36]. |

| Fuzzy Inference Engine (FIE) | A rule-based deterministic algorithm that uses a set of functions and rules to map similarity scores onto weights for determining matches. Highly tunable and can achieve high precision [36]. |

| Expectation-Maximization (EM) Algorithm | A probabilistic method for finding maximum-likelihood estimates of parameters in statistical models. Used in the Fellegi-Sunter probabilistic entity resolution model to estimate m and u probabilities [36]. |

| Levenshtein Edit Distance | A string metric for measuring the difference between two sequences. Calculates the minimum number of single-character edits required to change one word into the other. Used for calculating similarity between text fields [36]. |

| Active Learning Sampling | A machine learning strategy where the algorithm chooses the most informative data points to be labeled by an expert. Reduces the total amount of labeled data required for training [36]. |

| Blocking / Indexing | A method to reduce the computational cost of entity resolution by grouping records into "blocks" and only comparing records within the same block. Critical for scaling to large datasets [36] [34]. |

Integrating AI and Machine Learning for Smarter, Context-Aware Screening

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) into data screening processes. A core challenge in this integration is managing false positives—instances where the system incorrectly flags a negative case as positive [40]. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodologies to help you diagnose, understand, and mitigate these issues, ensuring your AI tools are both smart and reliable.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing a High Rate of False Positives

A high false positive rate can overwhelm resources and obscure true results.

- Problem: Your AI screening system is generating an unexpectedly large number of false alerts.

- Symptoms: Low precision; too many non-relevant cases requiring manual review.

- Impact: Wasted computational and human resources, potential missed true positives due to alert fatigue.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

Audit Your Training Data

- Action: Check the labels in your training dataset for inaccuracies. A model trained on mislabeled data will learn incorrect patterns [41].

- How: Manually review a sample of data points that were used to train the model, especially those from the classes contributing most to the false positives.

Conduct an Error Analysis

- Action: Systematically analyze the cases your model is getting wrong [41].

- How: Create a new dataset containing both the target and model-predicted values. Group this data by feature categories and calculate the accuracy and error rate for each group. This will identify specific scenarios where your model fails (e.g., "The model has a 70% error rate for customers with a 'Month-to-month' contract") [41].

Evaluate Feature Relevance

- Action: Determine if the model is using features that are not causally linked to the outcome.

- How: Use model interpretation tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) to see which features are driving the predictions for the false positive cases. Irrelevant features can lead the model astray.

Tune the Decision Threshold

- Action: Adjust the probability threshold used to classify a case as "positive."

- How: By default, this threshold is often 0.5. Increasing it to a higher value (e.g., 0.7 or 0.8) will make the model more conservative, only making a positive classification when it is more confident, thereby reducing false positives.

Implement a Replicate Testing Strategy

- Action: For critical screenings, don't rely on a single model decision. Use a majority rule strategy on multiple tests [42].

- How: Run multiple independent assays or model inferences on the same sample. A case is only considered a true positive if it returns a positive result in a majority of the tests (e.g., 2 out of 3). This strategy exponentially reduces the effective false-positive rate [42].

Guide 2: Dealing with a "Black Box" Model That Lacks Explainability

Regulators and stakeholders need to understand why an AI system makes a decision.

- Problem: Your model's predictions are not interpretable, making it difficult to explain alerts to colleagues or regulators [43].

- Symptoms: Inability to answer the question, "Why did the system flag this specific case?"

- Impact: Eroded trust in the system, regulatory compliance risks, and difficulty diagnosing model errors [43].

Step-by-Step Resolution:

Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) Methods

- Action: Use post-hoc explanation tools to shed light on individual predictions.

- How: Employ libraries like

SHAPorLIMEto generate "reason codes" for each prediction. These tools can highlight the top features that contributed to a specific classification, turning a black-box prediction into an interpretable report.

Ensure Comprehensive Documentation

Create an Auditable Trail

- Action: Ensure that every decision made by the AI system can be reconstructed and reviewed later [43].

- How: Log all inputs, the model's version, the resulting prediction, and the confidence score for every screening event. This creates a reliable record for internal audits and regulatory inquiries.

Validate with Domain Experts

- Action: Partner with subject-matter experts to review the model's explanations.

- How: Regularly present the model's top false positive cases and the corresponding XAI reason codes to domain experts. Their feedback will help you validate if the model's "reasoning" is sound and align the model's behavior with domain knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our AI model performs well on validation data but fails in production with real-world data. What could be the cause? A: This is often a sign of data drift or a training-serving skew. The data your model sees in production has likely changed from the data it was trained and validated on. To address this:

- Monitor Data Distributions: Continuously monitor the statistical properties of incoming production data and compare them to your training set.

- Establish MLOps Practices: Implement robust Machine Learning Operations (MLOps) to manage, version, and monitor models and data continuously, preventing the deployment of brittle systems [44].

- Retrain Regularly: Schedule periodic model retraining with freshly labeled production data to keep the model adapted to current conditions.

Q2: How can we measure the true business impact of false positives in our screening process? A: Beyond technical metrics like precision, you should track operational costs. Key performance indicators (KPIs) include:

- Time-to-Investigation: The average time analysts spend reviewing a false positive alert.

- Resource Allocation: The percentage of total analyst hours consumed by false positives.

- Opportunity Cost: The number of true positive investigations that were delayed or missed due to time spent on false alerts. Tracking these metrics helps build a business case for investing in AI model refinement.

Q3: What is the regulatory stance on using AI for critical screening, such as in drug development or financial compliance? A: Regulators welcome innovation but emphasize accountability. The core principle is that technology does not transfer accountability [43]. Institutions, not algorithms, are held responsible for failures. Key expectations include:

- Explainability: The ability to understand and explain the logic behind the system's decisions [43].

- Governance: A documented framework for how models are designed, validated, and controlled [43].

- Human Oversight: A hybrid approach where AI handles bulk data, but humans focus on complex, high-stakes investigations is considered most defensible [43].

Q4: Are simpler models like logistic regression sometimes better than complex deep learning models for screening? A: Yes, absolutely. A common mistake is chasing complexity before nailing the basics [44]. Simpler models like linear regression or pre-trained models often provide greater ROI, are easier to interpret and debug, and require less data. You should always start simple to establish a baseline and only increase complexity if it yields a significant and necessary improvement [44].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Replicate Testing with Majority Rule for False Positive Reduction

This methodology is designed to minimize the dilution of efficacy estimates in clinical trials or the accumulation of false positives in screening caused by imperfect diagnostic assays or AI models [42].

1. Principle If multiple repeated runs of an assay or model inference can be treated as independent, requiring multiple positive results to confirm a case can drastically reduce the effective false positive rate.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: For a given sample, perform

nindependent tests (wherenis an odd number, typically 3). - Step 2: Apply a "majority rule." A case is only confirmed as positive if at least

mtests return a positive result, wherem = (n/2 + 1). - Step 3: Calculate the new, effective false positive rate (

FP_n,m) using the binomial distribution formula [42]:FP_n,m = Σ (from k=m to n) of [n!/(k!(n-k)!] * FP^k * (1-FP)^(n-k)WhereFPis the original false positive rate of a single test.

3. Application Example This strategy is particularly powerful in clinical trials where frequent longitudinal testing is required. It prevents the accumulation of false positives over time, which would otherwise systematically bias (dilute) the estimated efficacy of an intervention downward [42].

Performance Data of Selected AI Detection Tools

The following table summarizes the performance of various AI detection tools as reported in recent studies. Note: Performance is highly dependent on the specific versions of the AI and detection tools and can change rapidly. This data should be used to understand trends, not to select a specific tool [45].

Table 1: Accuracy of Tools in Identifying AI-Generated Text

| Tool Name | Kar et al. (2024) | Lui et al. (2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Copyleaks | 100% | |

| GPT Zero | 97% | 70% |

| Originality.ai | 100% | |

| Turnitin | 94% | |

| ZeroGPT | 95.03% | 96% |

Table 2: Overall Accuracy in Discriminating Human vs. AI Text

| Tool Name | Perkins et al. (2024) | Weber-Wulff (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Crossplag | 60.8% | 69% |

| GPT Zero | 26.3% | 54% |

| Turnitin | 61% | 76% |

Source: Adapted from Jisc's National Centre for AI [45].

Key Insight: Mainstream, paid detectors like Turnitin are engineered for educational use and prioritize a low false positive rate (often cited as 1-2%), which is crucial in high-stakes environments where false accusations are harmful [45].

Visualizing the AI Screening Pipeline

Workflow for AI-Powered Screening with Human Oversight

This diagram illustrates a robust and defensible workflow for integrating AI into a screening process, emphasizing human oversight and continuous improvement to manage false positives.

Replicate Testing Strategy Logic

This diagram outlines the decision-making process for the replicate testing "majority rule" strategy used to minimize false positives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Components for an AI Screening Research Pipeline

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Labeled Data | The foundational reagent. AI models learn from data; inaccurate, incomplete, or biased labels will directly lead to high false positive rates and poor model performance [43] [41]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Library | A tool for model diagnosis. Libraries like SHAP or LIME help interpret "black box" models by identifying which features contributed most to a specific prediction, which is crucial for troubleshooting and regulatory compliance [43]. |

| A/B Testing Platform | The framework for objective evaluation. This allows you to test a new model against a current one in production to see which performs better on real-world data, preventing the deployment of models that degrade performance [44]. |

| MLOps Platform | The infrastructure for sustainable AI. MLOps (Machine Learning Operations) provides tools for versioning data and models, monitoring performance, and managing pipelines, preventing systems from becoming brittle and unmaintainable [44]. |

| Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | (For clinical/biological contexts) A confirmatory test. When an initial immunoassay screen (or AI-based screen) returns a positive result, GC-MS provides a highly accurate, definitive analysis to rule out false positives, setting a gold standard for verification [40]. |

Troubleshooting and Optimizing Screening Systems for Maximum Efficiency

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High False Positive Rates in Screening Data

Problem: My screening experiments are generating an unmanageably high number of false positive alerts, overwhelming analytical resources and obscuring true results.

Solution: A systematic approach targeting the root causes of false positives, from data entry to algorithmic matching.

1. Check Data Completeness and Standardization:

- Action: Verify that critical data fields (e.g., compound IDs, sample identifiers, subject names) contain no null or missing values. Ensure data conforms to standardized formats (e.g., dates, units of measure).