The Complete RNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide from Raw Data to Biological Insight

This article provides a comprehensive guide to RNA-seq data analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Complete RNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide from Raw Data to Biological Insight

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to RNA-seq data analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of transcriptomics, a detailed methodological walkthrough from quality control to differential expression analysis, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing pipelines for specific research needs, and finally, methods for validating results and comparing analytical approaches. By synthesizing current best practices and addressing common pitfalls, this guide empowers users to transform raw sequencing data into robust, biologically meaningful conclusions, with a particular focus on applications in biomarker discovery and clinical research.

Understanding the RNA-seq Landscape: From Experimental Principles to Data Exploration

Technological Comparison: RNA-seq vs. Microarrays

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for transcriptome analysis, offering significant advantages over legacy microarray technology. The table below provides a structured comparison of their technical capabilities.

Table 1: Key Technical Differences Between RNA-seq and Microarrays

| Feature | RNA-seq | Microarrays |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Direct, high-throughput sequencing of cDNA [1] | Hybridization of labeled cDNA to immobilized DNA probes [2] [1] |

| Transcriptome Coverage | Comprehensive; detects known, novel, and non-coding RNAs [3] [2] | Limited to predefined, known transcripts [4] [2] |

| Dynamic Range | >10⁵ (Wide) [3] [1] | ~10³ (Narrow) [3] [1] |

| Specificity & Sensitivity | High; superior for detecting low-abundance transcripts and differential expression [3] [1] | Moderate; limited by background noise and cross-hybridization [4] [1] |

| Required Prior Knowledge | None; applicable to any species, even without a reference genome [5] [2] | Required for probe design; limited to well-annotated genomes [4] [2] |

| Primary Data Output | Digital read counts [4] | Analog fluorescence intensity values [4] |

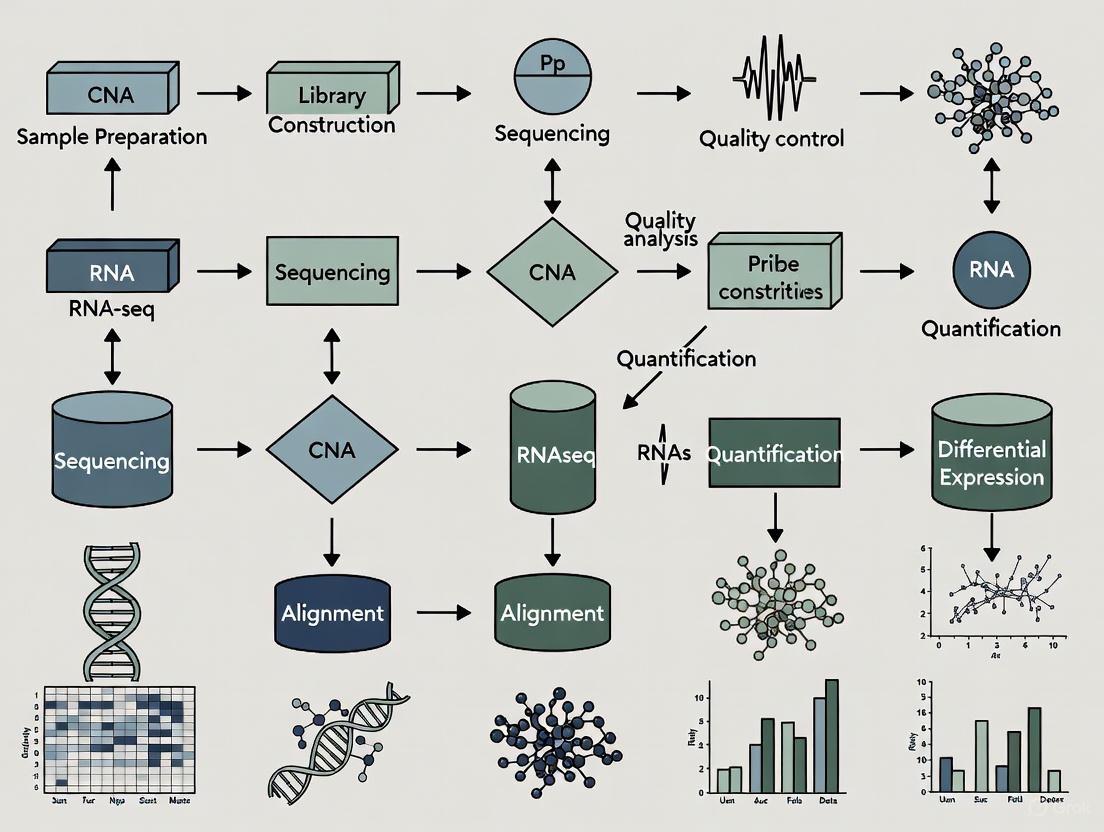

The diagram below illustrates the core methodological divergence between the two technologies and the consequent advantages of RNA-seq.

Key Applications in Biomedical Research

The unique advantages of RNA-seq have enabled its widespread adoption across diverse biomedical research domains, far surpassing the application range of microarrays.

Table 2: Key Applications of RNA-seq in Biomedical Research

| Application Domain | Specific Applications | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Oncology & Biomarker Discovery | Detection of expressed mutations, gene fusions, and allele-specific expression [5] [6] | Guides therapeutic decisions by identifying actionable, expressed mutations; more relevant than DNA presence alone [6] |

| Transcriptome Structure & Regulation | Characterization of alternative splicing patterns, identification of novel transcripts and isoforms [5] [2] | Reveals complex regulatory mechanisms underlying diseases like Alzheimer's and cancer [5] [7] |

| Drug Discovery & Development | Uncovering novel therapeutic targets, understanding drug mechanism of action and off-target effects [5] [7] | Enables more precise and efficient drug development pipelines, particularly in oncology [7] |

| Single-Cell and Microbial Analysis | Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-Seq), taxonomic and functional profiling of microbiomes [5] [2] | Resolves cellular heterogeneity and profiles complex microbial communities, including uncultured species [5] [2] |

| Toxicogenomics and Safety Assessment | Concentration-response modeling for transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) analysis [8] | Provides quantitative data for chemical risk assessment in regulatory decision-making [8] |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard RNA-seq Workflow

A robust RNA-seq workflow involves multiple critical steps, from sample preparation to data interpretation. The following protocol outlines a standard pipeline for differential expression analysis.

Detailed Methodological Steps

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Library Construction

- RNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality total RNA using silica-membrane columns or phenol-chloroform extraction. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8) using instruments such as Agilent Bioanalyzer [8].

- Library Preparation: Select kit based on application (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep for coding RNA). Process includes:

- mRNA Enrichment: Use poly-A selection for eukaryotic mRNA or ribodepletion for total RNA (including bacterial RNA and non-coding RNAs) [3].

- cDNA Synthesis: Fragment RNA and reverse transcribe to double-stranded cDNA using random hexamers or oligo-dT primers [2].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters, often incorporating sample index barcodes for multiplexing [2].

Step 2: Sequencing

- Utilize high-throughput platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq X series for large-scale projects or Thermo Fisher Ion Torrent Genexus System for automated, integrated workflows [7].

- Sequencing Depth: Aim for 20-50 million paired-end reads per sample for standard differential expression analysis in model organisms. Deeper coverage (>80 million reads) is recommended for de novo transcriptome assembly or low-abundance transcript detection [9].

Step 3: Bioinformatics Data Processing

- Quality Control & Trimming: Use FastQC for initial quality assessment. Trim low-quality bases and adapter sequences using tools like fastp or Trim Galore [10] [9].

- Alignment: Map cleaned reads to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or HISAT2. For organisms without a reference genome, perform de novo assembly using Trinity or SOAPdenovo-Trans [9].

- Quantification: Generate count matrices for genes and transcripts using tools like featureCounts, HTSeq-count, or kallisto, which assign reads to genomic features [9].

Step 4: Differential Expression and Functional Analysis

- Differential Expression: Identify statistically significant expression changes between conditions using tools such as DESeq2, edgeR, or NOISeq. These tools model count data using negative binomial distributions and normalize for library size and composition [10] [9].

- Functional Profiling: Interpret biological meaning through functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes using databases like Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG, and Reactome via tools such as DAVID or clusterProfiler [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq

| Item/Category | Function and Examples |

|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | Convert RNA into sequence-ready libraries. Examples: Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep (for mRNA), Illumina Total RNA-Seq kits (for all RNA species) [8] [7]. |

| RNA Integrity Tools | Assess sample quality. Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA Nano Kit to calculate RNA Integrity Number (RIN); a RIN >8 is typically recommended [8]. |

| Targeted Panels | Focus sequencing on genes of interest for cost-effective, deep coverage. Examples: Afirma Xpression Atlas (XA) for thyroid cancer, Thermo Fisher panels for hematologic cancers [6] [7]. |

| Alignment & Quantification Software | Map reads and determine expression levels. Examples: STAR (splice-aware aligner), HISAT2 (memory-efficient aligner), kallisto (pseudoalignment for fast quantification) [9]. |

| Differential Expression Tools | Identify statistically significant gene expression changes. Examples: DESeq2, edgeR, and NOISeq, which use specific statistical models for RNA-seq count data [10] [9]. |

| Functional Annotation Databases | Provide biological context. Examples: Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG, DAVID, and STRING for pathway and network analysis [9]. |

The transcriptome represents the complete set of transcripts in a cell, including their identities and quantities, for a specific developmental stage or physiological condition [11]. Understanding the transcriptome is fundamental for interpreting the functional elements of the genome, revealing the molecular constituents of cells and tissues, and understanding development and disease [11]. The primary aims of transcriptomics include cataloging all transcript species (including mRNAs and non-coding RNAs), determining the transcriptional structure of genes (start sites, splicing patterns, and other modifications), and quantifying the changing expression levels of each transcript during development and under different conditions [11].

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a revolutionary tool for transcriptome analysis, largely replacing hybridization-based approaches such as microarrays [11] [10]. This sequence-based approach utilizes deep-sequencing technologies to profile transcriptomes, offering a far more precise measurement of transcript levels and their isoforms than previous methods [11]. RNA-seq works by converting a population of RNA (either total or fractionated) into a cDNA library with adaptors attached to one or both ends. Each molecule is then sequenced in a high-throughput manner to obtain short sequences (typically 30-400 bp) from one end (single-end sequencing) or both ends (paired-end sequencing) [11]. The resulting reads are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome, or assembled de novo without a reference sequence to produce a genome-scale transcription map [11].

Key Technological Concepts and Advantages

From Microarrays to RNA-seq: A Paradigm Shift

The transition from microarray technology to RNA-seq represents a significant advancement in transcriptomics. Hybridization-based approaches, while high-throughput and relatively inexpensive, suffer from several limitations including reliance on existing genome knowledge, high background levels from cross-hybridization, limited dynamic range due to signal saturation, and difficulties in comparing expression levels across different experiments [11].

RNA-seq offers several distinct advantages over these earlier technologies. First, it is not limited to detecting transcripts that correspond to existing genomic sequence, making it particularly valuable for non-model organisms [11]. Second, it can reveal the precise location of transcription boundaries to single-base resolution [11]. Third, RNA-seq has very low background signal because DNA sequences can be unambiguously mapped to unique genomic regions [11]. Fourth, it possesses a substantially larger dynamic range for detecting transcripts—exceeding 9,000-fold compared to microarrays' several-hundredfold range—enabling detection of genes expressed at both very low and very high levels [11]. Finally, RNA-seq requires less RNA sample and provides both single-base resolution for annotation and 'digital' gene expression levels at the genome scale, often at lower cost than previous methods [11].

Understanding Sequencing Reads

The fundamental data units generated by RNA-seq are called reads, which are short DNA sequences derived from fragmented RNA transcripts [11]. These reads can be characterized by several key parameters:

- Read Length: Typically 30-400 base pairs, depending on the sequencing technology used [11]

- Sequencing Depth: The total number of reads obtained, which affects detection sensitivity and quantification accuracy [12]

- Read Type: Either single-end (sequenced from one end) or paired-end (sequenced from both ends), with the latter providing more structural information [11]

Different sequencing platforms produce reads with varying characteristics. The Illumina, Applied Biosystems SOLiD, and Roche 454 Life Science systems have all been applied for RNA-seq, each with distinct read length and accuracy profiles [11]. Recent advances in long-read RNA-seq technologies from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) can generate full-length transcript sequences, overcoming the limitation of short reads in reconstructing complex isoforms [12].

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Technologies and Their Characteristics

| Technology | Read Length | Throughput | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-read (Illumina) | 50-300 bp | High | Differential expression, transcript quantification | High accuracy, low cost | Limited isoform resolution |

| PacBio cDNA | Long (1-15 kb) | Moderate | Full-length isoform detection | High consensus accuracy | Higher RNA input requirements |

| ONT Direct RNA | Variable | Moderate | Native RNA analysis, modification detection | No cDNA bias, detects modifications | Higher error rate |

| CapTrap | Variable | Moderate | 5'-capped RNA enrichment | Complete 5' end representation | Protocol complexity |

The Central Question of Differential Expression

Defining Differential Expression Analysis

Differential expression (DE) analysis represents one of the most common and critical applications of RNA-seq technology [13]. The central question it addresses is: "Which genes exhibit statistically significant differences in expression levels between two or more biological conditions?" These conditions might include disease states versus healthy controls, different developmental stages, treated versus untreated samples, or various tissue types [13] [14].

The identification of differentially expressed genes enables researchers to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic differences, discover potential biomarkers for diseases (including cancer), identify drug targets, and reveal host-pathogen interactions [13]. In drug development, differential expression analysis can identify mechanisms of action, assess drug efficacy, discover predictive biomarkers, and understand resistance mechanisms [13].

Statistical Foundations and Challenges

Differential expression analysis involves comparing normalized count data between experimental conditions to identify genes with expression changes greater than what would be expected by random chance alone [13]. This requires appropriate statistical models that account for biological variability and technical noise inherent in RNA-seq data.

Several statistical approaches have been developed, each with different underlying distributional assumptions [13]:

- Negative Binomial Distribution: Used by tools like DESeq2 and edgeR to model over-dispersed count data

- Log-Normal Distribution: Employed by limma-voom after transformation of count data

- Poisson Distribution: Suitable for technical replicates but less common for biological replicates

- Non-parametric Methods: Used by SAM-seq for data that doesn't fit standard distributions

The choice of statistical approach significantly impacts the results, with negative binomial and log-normal based methods generally recommended for most applications [13]. These tools help control for false positives while maintaining sensitivity to detect true biological differences.

RNA-seq Workflow and Methodologies

Comprehensive Experimental Protocol

A standard RNA-seq protocol for differential expression analysis involves both wet-lab procedures and computational analysis [14]. The experimental workflow typically includes:

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction:

- Collect biological replicates for each condition (minimum 3 recommended)

- Extract total RNA using appropriate methods (e.g., column-based purification)

- Assess RNA quality using methods such as Bioanalyzer to ensure RIN > 8

Library Preparation:

- Select and enrich RNA fractions (e.g., poly(A)+ selection for mRNA)

- Fragment RNA (if using short-read platforms) to 200-500 bp fragments

- Convert to cDNA with adaptor ligation

- Amplify library (unless using amplification-free methods)

- Quality control and quantification of final library

Sequencing:

- Utilize appropriate sequencing platform (Illumina, PacBio, or ONT)

- Aim for sufficient depth (typically 20-50 million reads per sample for mammalian genomes)

- Include controls (e.g., spike-in RNAs) for normalization [12]

Computational Analysis:

- Quality control of raw reads

- Read alignment and quantification

- Differential expression testing

- Functional interpretation

Bioinformatics Workflow

The computational analysis of RNA-seq data involves multiple steps, each requiring specific tools and approaches [10] [9]:

Figure 1: RNA-seq Bioinformatics Workflow

Quality Control and Trimming: Initial quality assessment of raw sequencing reads is crucial for detecting sequencing errors, contaminants, and PCR artifacts [10] [9]. Tools such as FastQC provide comprehensive quality metrics, while trimming tools like fastp or Trim Galore remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases to improve mapping rates [10]. Key parameters to assess include sequence quality, GC content, adapter content, overrepresented k-mers, and duplicated reads [9].

Read Alignment: Three primary strategies exist for aligning processed reads [9]:

- Genome Mapping: Aligning reads to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners (e.g., STAR, HISAT2)

- Transcriptome Mapping: Direct alignment to reference transcript sequences

- De Novo Assembly: Reconstructing transcripts without a reference genome using tools like Trinity

The choice of strategy depends on reference genome availability and quality, with genome-based approaches generally preferred when high-quality references exist [9].

Transcript Quantification: This step estimates gene and transcript expression levels from aligned reads [15] [9]. Tools like RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) and kallisto account for multi-mapping reads (those that align to multiple genomic locations) and allocate them probabilistically among transcripts [15]. RSEM is particularly notable as it can work with or without a reference genome, making it valuable for non-model organisms [15]. For accurate quantification, it's essential to use methods that properly handle ambiguously-mapping reads rather than simply discarding them [15].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Differential Expression Tools

| Tool | Statistical Distribution | Normalization Method | Replicates Required | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial | Median of ratios | Recommended | Standard DE analysis with biological replicates |

| edgeR | Negative Binomial | TMM, RLE | Required | Experiments with small sample sizes |

| limma-voom | Log-Normal | TMM | Recommended | Complex experimental designs |

| Cufflinks | Poisson | FPKM | Not required | Isoform-level differential expression |

| SAMseq | Non-parametric | Internal | Recommended | Data not fitting standard distributions |

Differential Expression Analysis: This final analytical step identifies genes with statistically significant expression changes between conditions [13]. The choice of tool depends on experimental design, replication, and data characteristics. DESeq2 and edgeR are widely used methods that employ negative binomial distributions to model count data and account for biological variability [13]. Both tools require raw count data as input and perform their own normalization procedures to correct for library size and composition biases [13].

Functional Profiling: The final step typically involves biological interpretation of differential expression results through functional enrichment analysis [9]. Tools for Gene Ontology analysis, pathway enrichment (KEGG, Reactome), and network analysis help place the molecular changes in biological context, identifying affected processes, pathways, and functions.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA integrity immediately after sample collection | RNAlater, TRIzol, PAXgene |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enrich for polyadenylated mRNA | Oligo(dT) magnetic beads |

| RNA Fragmentation Reagents | Fragment RNA to appropriate size for sequencing | Metal cations, heat, enzymatic fragmentation |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesize cDNA from RNA templates | SuperScript IV, Maxima H-minus |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries with adaptors | Illumina TruSeq, NEB Next Ultra II |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | Generate cDNA for long-read sequencing | PacBio SMRTbell, ONT cDNA |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Normalization and quality control | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix, SIRV sets |

| Quality Control Assays | Assess RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, Qubit |

Advanced Considerations and Recent Developments

Long-Read RNA Sequencing Technologies

Recent advances in long-read RNA sequencing (lrRNA-seq) technologies have transformed transcriptome analysis by enabling full-length transcript sequencing [12]. The Long-read RNA-Seq Genome Annotation Assessment Project (LRGASP) Consortium systematically evaluated these methods, revealing that libraries with longer, more accurate sequences produce more accurate transcripts than those with increased read depth, while greater read depth improved quantification accuracy [12].

Key findings from lrRNA-seq assessments include:

- cDNA-PacBio and R2C2-ONT datasets produce the longest read-length distributions

- Sequence quality is higher for CapTrap-PacBio, cDNA-PacBio and R2C2-ONT than other approaches

- For well-annotated genomes, reference-based tools demonstrate the best performance

- Incorporating orthogonal data and replicate samples is advised for detecting rare and novel transcripts

Experimental Design Considerations

Proper experimental design is crucial for robust differential expression analysis. Key considerations include:

Replication:

- Biological replicates (different biological units) are essential for capturing natural variation

- Technical replicates (same sample processed multiple times) help assess technical noise

- Minimum 3 biological replicates per condition recommended, with more for subtle effects

Sequencing Depth:

- Balance between sufficient depth for detection and cost considerations

- Typically 20-50 million reads per sample for standard differential expression in mammalian genomes

- Increased depth required for detecting low-abundance transcripts or complex isoforms

Batch Effects:

- Distribute experimental conditions across sequencing batches

- Randomize processing order to avoid confounding technical and biological variation

- Use statistical methods like COMBAT or ARSyN to correct for batch effects when unavoidable

Method Selection and Benchmarking

With numerous available tools for each step of RNA-seq analysis, selection of appropriate methods is challenging. Recent benchmarking studies provide guidance:

- For differential expression, DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom generally show good performance [13]

- For transcript quantification, methods like RSEM that properly handle multi-mapping reads outperform simple count-based approaches [15]

- Performance of analytical tools can vary across species, suggesting that optimization for specific organisms may be necessary [10]

- For alternative splicing analysis, rMATS demonstrates good performance for detecting differentially spliced isoforms [10]

RNA-seq has fundamentally transformed transcriptomics by providing an unprecedented detailed view of transcriptomes. Understanding the core concepts of transcriptomes, sequencing reads, and differential expression analysis is essential for designing, executing, and interpreting RNA-seq experiments effectively. The continuous development of both experimental protocols and computational methods ensures that RNA-seq will remain a cornerstone technology for biological discovery and translational research, particularly in drug development where understanding gene expression changes is critical for target identification, mechanism elucidation, and biomarker discovery.

As the field evolves, integration of long-read technologies, single-cell approaches, and multi-omics frameworks will further enhance our ability to address the central question of differential expression across diverse biological contexts and experimental conditions.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has revolutionized transcriptomic research, providing a powerful tool for large-scale inspection of mRNA levels in living cells [16]. This application note outlines the complete end-to-end RNA-Seq data analysis workflow, from raw sequencing data to biological interpretation. The protocol is designed to enable researchers and drug development professionals to perform differential gene expression analysis, gaining critical insights into gene function and regulation that can inform therapeutic development and biomarker discovery.

Experimental Design and Data Acquisition

A successful RNA-Seq study begins with a well-considered experimental design that ensures the generated data can answer the biological questions of interest [17]. Key considerations include:

- RNA Extraction Protocol: Choose between poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment or ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion. Poly(A) selection requires high-quality RNA with minimal degradation, while ribosomal depletion is suitable for lower-quality samples or bacterial studies where mRNA lacks polyadenylation [17].

- Library Strandedness: Strand-specific protocols preserve information about the originating DNA strand, crucial for analyzing antisense or overlapping transcripts [17].

- Sequencing Configuration: Paired-end reads are preferable for de novo transcript discovery or isoform expression analysis, while single-end reads may suffice for gene expression studies in well-annotated organisms [17].

- Sequencing Depth: Deeper sequencing (more reads) enables detection of more transcripts and improves quantification precision, particularly for lowly-expressed genes. Requirements vary from as few as 5 million mapped reads for medium-highly expressed genes to 100 million reads for comprehensive transcriptome coverage [17].

- Replication: The number of biological replicates depends on technical variability, biological variability, and desired statistical power for detecting differential expression [17].

Table 1: Key Experimental Design Decisions in RNA-Seq

| Design Factor | Options | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Selection | Poly(A) enrichment | Requires high RNA integrity; captures only polyadenylated transcripts |

| rRNA depletion | Works with degraded samples (e.g., FFPE); captures non-polyadenylated RNA | |

| Library Type | Strand-specific | Preserves strand information; identifies antisense transcripts |

| Non-stranded | Standard approach; lower cost | |

| Sequencing Type | Single-end | Cost-effective; sufficient for basic expression quantification |

| Paired-end | Better for isoform analysis, novel transcript discovery | |

| Read Length | 50-300 bp | Longer reads improve mappability, especially across splice junctions |

Computational Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of RNA-Seq data transforms raw sequencing files into interpretable biological results through a multi-step process.

From Raw Reads to Read Counts

Quality Control of Raw Reads Initial quality assessment checks sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, overrepresented k-mers, and duplicated reads to identify sequencing errors or PCR artifacts [17]. FastQC is commonly used for this analysis [17] [16]. Trimmomatic or the FASTX-Toolkit can remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences [17] [16].

Read Alignment Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using tools such as HISAT2, STAR, or TopHat2 [16] [18]. Alignment quality metrics include the percentage of mapped reads (expected 70-90% for human genome), read coverage uniformity across exons, and strand specificity [17]. The output is typically in SAM/BAM format [19].

Quantification Aligned reads are assigned to genomic features (genes, transcripts) using quantification tools like featureCounts or HTSeq [16] [18]. This generates a count matrix where each value represents the number of reads unambiguously assigned to a specific gene in a particular sample [19]. It is crucial that these values represent raw counts, not normalized values, for subsequent statistical analysis [19].

Differential Expression Analysis

Data Normalization and Modeling Count matrices are imported into statistical environments such as R/Bioconductor for differential expression analysis [19]. Methods like DESeq2, edgeR, or limma-voom employ specific normalization approaches to account for differences in library size and RNA composition, then model expression data using statistical distributions (typically the negative binomial distribution for count data) [19].

Statistical Testing and Results Extraction These tools test each gene for statistically significant differences in expression between experimental conditions, generating measures of effect size (fold change) and significance (p-value, adjusted p-value) [19]. Results can be visualized through MA-plots, volcano plots, and heatmaps to identify patterns of differential expression [16].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Essential Tools for RNA-Seq Data Analysis

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality Control | Assesses raw read quality | Identifies sequencing errors, adapter contamination, GC biases [17] [16] |

| Trimmomatic | Preprocessing | Trims adapters, low-quality bases | Improves mappability by removing poor sequence ends [17] [16] |

| HISAT2 | Alignment | Aligns reads to reference genome | Efficient for splice-aware alignment; faster than earlier tools [16] |

| STAR | Alignment | Aligns reads to reference genome | Excellent for detecting splice junctions; higher resource requirements [19] |

| featureCounts | Quantification | Assigns reads to genomic features | Generates count matrix from aligned reads [16] |

| DESeq2 | Differential Expression | Identifies differentially expressed genes | Uses negative binomial model; robust for experiments with limited replicates [19] |

| edgeR | Differential Expression | Identifies differentially expressed genes | Similar statistical model to DESeq2; different normalization approaches [19] [18] |

| R/Bioconductor | Analysis Environment | Statistical analysis and visualization | Comprehensive ecosystem for genomic data analysis [19] |

Quality Control Checkpoints

Robust RNA-Seq analysis requires quality assessment at multiple stages to ensure data integrity and reliability of conclusions [17].

Post-Alignment QC After read alignment, tools like Picard, RSeQC, or Qualimap assess mapping statistics, including the percentage of mapped reads, uniformity of exon coverage, and detection of 3' bias (indicative of RNA degradation) [17]. For mammalian genomes, 70-90% of reads should typically map to the reference [17].

Post-Quantification QC Following transcript quantification, checks for GC content and gene length biases inform appropriate normalization methods [17]. For well-annotated genomes, analyzing the biotype composition of the sample (e.g., mRNA vs. rRNA content) provides insights into RNA purification efficiency [17].

Batch Effect Mitigation Technical variability from different sequencing runs, library preparation dates, or personnel should be minimized through experimental design [18]. When processing samples in batches, include controls in each batch and randomize sample processing [17].

Advanced Analysis and Interpretation

Exploratory Data Analysis Prior to formal differential expression testing, exploratory data analysis techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) visualize overall data structure, assessing sample similarity and identifying potential outliers [18]. PCA reduces the high-dimensional gene expression data to two or three dimensions that capture the greatest variance, allowing assessment of whether intergroup differences exceed intragroup variability [18].

Functional Enrichment Analysis Differentially expressed genes can be further analyzed for enrichment of biological pathways, Gene Ontology (GO) terms, or other functional annotations [18]. This moves beyond individual gene lists to identify biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular compartments that are statistically overrepresented among the differentially expressed genes.

Data Visualization Effective visualization techniques enhance interpretation of RNA-Seq results:

- Heatmaps: Display expression patterns of significant genes across samples, often with clustering to identify co-expressed genes [16].

- Volcano Plots: Visualize the relationship between statistical significance (p-value) and magnitude of change (fold change) for all tested genes [16].

- MA-Plots: Show the relationship between average expression intensity and fold change, highlighting potential biases [19].

A comprehensive understanding of the end-to-end RNA-Seq workflow empowers researchers to design robust experiments, implement appropriate analysis strategies, and accurately interpret results. This structured approach from experimental design through functional interpretation ensures maximum biological insight from transcriptomic datasets, supporting drug development and basic research applications. As RNA-Seq methodologies continue to evolve, maintaining this "big picture" perspective enables researchers to adapt new computational methods while maintaining rigorous analytical standards.

Within the broader context of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis workflow research, a thorough understanding of the core file formats is fundamental. The journey from raw sequencing data to biological insight is codified in a series of specialized files, each representing a distinct stage of processing and abstraction. This guide decodes three essential formats—FASTQ, BAM, and Count Matrices—detailing their structures, roles in the analytical pipeline, and the practical protocols for working with them. Mastery of these formats empowers researchers and drug development professionals to execute robust, reproducible transcriptomic analyses, forming the computational bedrock for advancements in molecular biology and personalized medicine [20].

RNA sequencing has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with high resolution and accuracy [20]. The transformation of a biological sample into interpretable gene expression data is a multi-stage computational process. Each stage produces a characteristic file format that encapsulates specific information:

- FASTQ files represent the raw output of sequencing instruments, containing the nucleotide sequences and their associated quality scores.

- BAM files contain the aligned sequences, representing where these reads map within a reference genome or transcriptome.

- Count Matrices are the final, summarized quantitative data, aggregating reads to estimate gene or transcript expression levels for each sample in an experiment.

This progression from raw sequences to a numerical matrix is critical for downstream statistical analysis, including the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [20]. The following workflow diagram illustrates the relationship between these core file formats and the key processing steps.

The File Formats: Structures and Functions

FASTQ: The Raw Sequencing Read Format

Function: The FASTQ format is the primary output of next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms. It stores the nucleotide sequences (reads) generated by the sequencer and, crucially, the per-base quality scores that indicate the confidence of each base call [21] [20]. This quality information is vital for assessing sequencing run success and for preprocessing.

Structure: Each sequence in a FASTQ file is represented by four lines:

- Line 1 (Sequence Identifier): Begins with an

@character and contains information about the sequencing instrument and run. - Line 2 (Raw Sequence Letters): The actual nucleotide sequence (A, C, G, T, N).

- Line 3 (Separator): A

+character, sometimes followed by the same identifier as line 1. - Line 4 (Quality Scores): A string of characters encoding the per-base Phred quality score, indicating the probability of a base call error.

Table: Key Characteristics of the FASTQ Format

| Characteristic | Description | Role in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Content | Nucleotide sequences (reads) | Represents fragments of the transcriptome present in the sample. |

| Quality Scores | Per-base Phred score (ASCII encoded) | Enables quality control; identifies low-quality bases for trimming. |

| File Size | Very large (often gigabytes) | Requires significant storage and computational resources. |

| Data Type | Raw, unprocessed data | The starting point for all downstream analysis. |

BAM/SAM: The Aligned Sequence Format

Function: The BAM (Binary Alignment/Map) file, and its text-based equivalent SAM, store the alignment information of sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. This step identifies the genomic origin of each RNA fragment, allowing researchers to determine which genes are being expressed [20]. The BAM format is binary, making it compressed and efficient for storage and indexing, whereas SAM is human-readable.

Structure: A BAM file consists of a header section and an alignment section.

- Header: Contains metadata about the reference sequence, the alignment program used, and the sorting order.

- Alignment Section: Each line represents a single read, containing key information such as the reference sequence name, mapping position, mapping quality (MAPQ), and the CIGAR string that details the alignment (e.g., matches, insertions, deletions).

Table: Key Characteristics of the BAM/SAM Format

| Characteristic | Description | Role in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Content | Alignment coordinates of reads | Locates transcribed fragments within the genome. |

| Mapping Quality | Per-read confidence in alignment | Allows filtering of poorly or ambiguously mapped reads. |

| CIGAR String | Compact string representing alignment | Details matches, mismatches, insertions, and deletions. |

| Binary vs. Text | BAM is compressed binary; SAM is text | BAM saves disk space and is faster to process. |

Count Matrix: The Gene Expression Quantification Format

Function: The count matrix is the final product of the data preprocessing pipeline and the direct input for differential expression analysis. It is a table that summarizes the number of sequencing reads assigned to each genomic feature (e.g., gene, transcript) for every sample in the study [20]. These "raw counts" are used by statistical tools like DESeq2 to identify genes that are significantly differentially expressed between conditions.

Structure: A count matrix is a two-dimensional table where:

- Rows represent genomic features (genes or transcripts).

- Columns represent individual samples or libraries.

- Cells contain integer values representing the number of reads that mapped to that feature in that sample.

Table: Example Structure of a Gene Count Matrix

| Gene | Sample1Control | Sample2Control | Sample3Treated | Sample4Treated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene_A | 150 | 165 | 2050 | 2100 |

| Gene_B | 50 | 45 | 55 | 60 |

| Gene_C | 2000 | 1800 | 100 | 150 |

Experimental Protocols for Data Processing

Protocol 1: From FASTQ to BAM - Read Alignment

This protocol covers the critical steps of quality control and alignment to convert raw sequencing data into aligned BAM files [21] [20].

Step 0: Software Installation

- Install the necessary bioinformatics tools using a package manager like Conda to ensure version control and reproducibility.

- Example Command:

Step 1: Quality Control of Raw FASTQ Files

- Objective: Assess sequencing quality and identify potential issues like adapter contamination or low-quality bases.

- Method: Use

FastQCto generate a quality report. Visually inspect the HTML output for warnings in modules like "Per Base Sequence Quality" and "Adapter Content" [21]. - Example Command:

Step 2: Trimming and Adapter Removal

- Objective: Clean the reads by removing adapter sequences, overrepresented sequences, and low-quality bases.

- Method: Use

Trimmomaticor a similar tool. Parameters must be set to balance data quality with retention of sufficient read length. - Example Command:

Step 3: Read Alignment to a Reference Genome

- Objective: Map each cleaned sequencing read to its correct location in the reference genome.

- Method: Use an aligner such as

HISAT2(commonly used for RNA-seq) orSTAR. First, download and index the reference genome for the organism of study. - Example Commands:

Step 4: SAM to BAM Conversion and Sorting

- Objective: Convert the human-readable SAM file to a compressed BAM file and sort it by genomic coordinate for efficient downstream analysis.

- Method: Use

samtools, a ubiquitous toolkit for handling aligned sequencing data. - Example Commands:

Protocol 2: From BAM to Count Matrix - Read Quantification

This protocol details the process of generating a gene-level count matrix from sorted BAM files, which is ready for statistical analysis [21] [20].

Step 1: Post-Alignment Quality Control

- Objective: Verify the quality of the alignments and identify any issues like high rates of multi-mapping reads.

- Method: Use tools like

Qualimaporsamtools statsto generate alignment statistics, including the percentage of uniquely mapped reads.

Step 2: Read Quantification with featureCounts

- Objective: Count the number of reads mapped to each gene.

- Method: Use

featureCounts(from theSubreadpackage) orHTSeq-count. These tools take the aligned BAM file and a reference annotation file (GTF/GFF) that defines the genomic coordinates of genes. - Example Command:

-T 4: Use 4 threads for computation.-p: Count fragments (for paired-end data) instead of reads.-a annotation.gtf: Specify the file with gene annotations.-o gene_counts.txt: Specify the output file.

Step 3: Consolidating the Count Matrix

- Objective: Combine the output from multiple samples into a single count matrix for downstream analysis in R or Python.

- Method: The output of

featureCountsis a text file. The count columns for all samples can be merged using custom scripts in R or Python, ensuring the rows (genes) are consistent across samples. The final matrix should look like the example in Section 2.3.

The following diagram visualizes the complete computational workflow from FASTQ files to a count matrix, incorporating the key steps from both protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software Solutions

The computational pipeline for RNA-seq data processing relies on a suite of software tools, each functioning as a critical "research reagent" to transform data from one format to the next.

Table: Essential Computational Tools for RNA-seq Analysis

| Tool / 'Reagent' | Function | Key Input | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC [21] | Quality control check of raw sequencing data. | FASTQ file | HTML report with quality metrics |

| Trimmomatic [21] | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases. | Raw FASTQ file | Cleaned/Trimmed FASTQ file |

| HISAT2 [21] [20] | Aligns RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. | Cleaned FASTQ file, Reference genome | SAM file |

| STAR [20] | Alternative, splice-aware aligner. | Cleaned FASTQ file, Reference genome | SAM file |

| Samtools [21] [20] | Manipulates alignments; converts, sorts, and indexes BAM files. | SAM/BAM file | Sorted, indexed BAM file |

| featureCounts [21] [20] | Quantifies reads mapped to genomic features. | Sorted BAM file, Annotation file (GTF) | Count matrix (text file) |

| R/Bioconductor (DESeq2) [21] | Performs statistical analysis for differential expression. | Count matrix | List of differentially expressed genes |

Robust RNA sequencing data is foundational to transcriptomic research, yet the biological conclusions drawn from an experiment are only as reliable as its initial design. Thoughtful experimental design is critical to ensure high-quality data and interpretable results, as no amount of statistical sophistication can separate confounded factors after data collection [22] [18]. This document outlines comprehensive protocols and application notes for key considerations in RNA-seq experimental design, including replication strategy, sequencing depth optimization, and library preparation selection, framed within the broader context of RNA-seq data analysis workflow research. These guidelines are essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to generate biologically meaningful transcriptomic data.

Experimental Design Considerations

The Critical Importance of Replication

Biological replicates—different biological samples representing the same condition—are absolutely essential for differential expression analysis as they allow measurement of the biological variation within a population [23]. The variation between biological replicates is typically greater than technical variation, and biological replication simultaneously counteracts random technical variation through independent sample preparation [24].

Protocol: Implementing Proper Replication Strategy

- Minimum Replicates: Include a minimum of 3 biological replicates per condition, though 5-6 is ideal for robust statistical power [25] [23].

- Cell Line Considerations: For cell line experiments, prepare replicates as independently as possible using different frozen cell stocks, freshly prepared media, and different growth factor batches [23].

- Pooling Strategy: If pooling is unavoidable due to material limitations, pool the same number of individuals for each condition and ensure pooled individuals are similar in sex, age, and other relevant factors. Each pooled set counts as a single replicate [23].

Table 1: Impact of Replication on Differential Expression Detection

| Replication Strategy | Statistical Power | Ability to Estimate Biological Variance | Cost Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Biological Replicates | Low | Limited | Moderate |

| 3-5 Biological Replicates | Good | Adequate | High |

| >5 Biological Replicates | Excellent | Robust | Lower |

| Technical Replicates Only | Very Low | None | Low |

Sequencing Depth Guidelines

Sequencing depth requirements vary significantly based on the specific research objectives and experimental questions. Generally, spending resources on more biological replicates provides better returns than increasing sequencing depth [23].

Protocol: Determining Optimal Sequencing Depth

- General Gene-Level Differential Expression: 15 million single-end reads per sample is often sufficient with good replication (>3 replicates). ENCODE guidelines suggest 30 million SE reads per sample (stranded) [23].

- Detection of Lowly-Expressed Genes: Sequence deeper with at least 30-60 million reads depending on the level of expression desired, starting with 30 million with adequate replication [23].

- Isoform-Level Analysis: For known isoforms, use at least 30 million paired-end reads per sample; for novel isoform discovery, use >60 million reads per sample [23].

Table 2: Sequencing Depth Recommendations by Experimental Goal

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Depth | Read Type | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-level DE | 15-30 million reads | SE or PE ≥50bp | More replicates preferred over depth |

| Low-expression DE | 30-60 million reads | PE ≥50bp | Balance depth with replication |

| Isoform-level (known) | ≥30 million reads | PE ≥50bp | Longer reads better for junctions |

| Isoform-level (novel) | >60 million reads | PE ≥50bp | Careful RNA QC essential |

| 3' mRNA-Seq (QuantSeq) | 1-5 million reads | SE or PE | Cost-effective for large screens |

Library Preparation Selection

The choice between whole transcriptome and 3' mRNA-seq approaches significantly impacts the information content, cost structure, and analytical requirements of an RNA-seq experiment [26].

Protocol: Selecting Library Preparation Method

Choose Whole Transcriptome/Total RNA-Seq if you need:

- A global view of all RNA types (coding and non-coding)

- Information about alternative splicing, novel isoforms, or fusion genes

- To work with samples where the poly(A) tail might be absent or highly degraded (e.g., prokaryotic RNA, some clinical samples) [26]

Choose 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq) if you need:

- Accurate and cost-effective gene expression quantification

- High-throughput screening of many samples

- A streamlined workflow with simpler data analysis

- To efficiently profile mRNA expression from degraded RNA and challenging sample types (like FFPE) [26]

Managing Technical Variation and Batch Effects

Technical variation in RNA-seq experiments stems from multiple sources, including differences in RNA quality/quantity, library preparation batch effects, flow cell and lane effects, and adapter bias [22]. Library preparation has been identified as the largest source of technical variation [22].

Protocol: Minimizing Batch Effects

- Randomization: Randomize samples during preparation and dilute to the same concentration [22].

- Multiplexing: Index and multiplex samples across all sequencing lanes/flow cells when possible [22].

- Blocking Design: When complete multiplexing isn't possible, use a blocking design that includes samples from each experimental group on each sequencing lane [22] [23].

- Metadata Collection: Meticulously record all potential batch effect sources (RNA isolation date, library prep date, researcher, reagents) for inclusion in statistical models [23].

Checklist for Identifying Batches

- Were all RNA isolations performed on the same day?

- Were all library preparations performed on the same day?

- Did the same person perform the RNA isolation/library preparation for all samples?

- Were the same reagents used for all samples?

- Was the RNA isolation/library preparation performed in the same location?

- If any answer is 'No', then batches exist and should be accounted for in experimental design and analysis [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for RNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Kits (e.g., NEBNext) | Enriches for mRNA by selecting polyadenylated transcripts | Standard for mRNA sequencing; misses non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| RiboMinus Kits | Depletes ribosomal RNA from total RNA | Preserves non-coding and non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| RiboZero Kits | Depletes ribosomal RNA from total RNA | Alternative ribosomal depletion method |

| Ultralow DR Library Kit | Library preparation for low input samples | Essential for limited clinical or sorted cell samples |

| QuantSeq 3' mRNA-Seq Kit | 3' focused library preparation | Ideal for high-throughput quantitative studies |

| Stranded mRNA-Seq Kit | Maintains strand information in library prep | Important for identifying antisense transcription |

| SPIA Amplification | Linear amplification of cDNA | Critical for low input samples to obtain sufficient material |

Comparative Analysis of Library Preparation Methods

Protocol: Performance Characteristics of WTS vs. 3' mRNA-Seq

A comparative study analyzing murine livers following normal or high iron diets demonstrated that both whole transcriptome and 3' mRNA-seq methods generate highly similar biological conclusions despite technical differences [26].

Key Findings:

- Whole Transcriptome Sequencing: Detects more differentially expressed genes and assigns more reads to longer transcripts, requiring stringent length normalization [26].

- 3' mRNA-Seq: Better detects short transcripts and provides more equal coverage across transcripts regardless of length, with simpler normalization requirements [26].

- Concordance: Both methods show high reproducibility between biological replicates and identify the same key biological pathways, though with some ranking differences in secondary pathways [26].

Practical Implementation Considerations:

- For 3' mRNA-Seq, ensure well-curated 3' annotation is available, especially for non-model organisms [26].

- Whole transcriptome sequencing requires careful quality control of RNA quality, particularly restricting analysis to high RIN samples when performing isoform-level analysis [23].

Proper experimental design remains the most critical factor in generating meaningful RNA-seq data. By carefully considering replication strategy, sequencing depth, library preparation methods, and batch effect management during the planning stages, researchers can ensure their experiments yield biologically interpretable results with minimal technical artifacts. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a framework for designing robust RNA-seq experiments that effectively address specific research questions while optimizing resource allocation in both academic and drug development contexts.

From Raw Reads to Results: A Practical Walkthrough of the Analysis Pipeline

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the initial quality control (QC) step is crucial for assessing the quality of raw sequencing data before proceeding with downstream analyses. High-throughput sequencing pipelines generate tremendous amounts of data that cannot be meaningfully interpreted without proper QC checks to identify potential issues that might compromise biological conclusions [27] [18]. Effective QC allows researchers to detect problems early, including sequencing errors, adapter contamination, or biases introduced during library preparation, thereby saving substantial time and effort in subsequent analysis stages.

The standard tool for initial QC assessment is FastQC, which provides a comprehensive evaluation of raw sequence data in FASTQ format. Following individual FastQC runs, MultiQC aggregates results from multiple samples and various bioinformatics tools into a single interactive report, enabling efficient comparison of QC metrics across all samples in an experiment [28] [29]. This combined approach provides researchers with a powerful framework for quality assessment, ensuring that only high-quality data progresses through the RNA-seq workflow, ultimately leading to more reliable and reproducible results in transcriptomic studies and drug development research.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Metrics

Understanding FASTQ Format and Sequencing Quality

RNA-seq data typically begins in FASTQ format, which stores called bases along with corresponding quality scores for each sequencing read [27]. The quality scores, expressed as Phred-scale values (Q), represent the probability of an incorrect base call. For example, Q30 denotes a 99.9% base call accuracy (1 error in 1,000 bases), and high-quality data should typically have over 80% of bases with Q30 or higher [27]. FastQC evaluates multiple aspects of this raw sequence data, generating metrics that help researchers identify potential issues before proceeding with alignment and quantification.

Critical Quality Control Metrics

FastQC examines several key metrics that provide insights into data quality. The per-base sequence quality assesses how quality scores change across read positions, typically showing a slight quality reduction toward read ends [27]. The adapter content metric identifies the presence of adapter sequences, which must be trimmed before alignment [27]. GC content evaluation checks whether the distribution of G and C nucleotides matches the expected organism-specific composition, while sequence duplication levels help identify potential technical duplicates or highly expressed transcripts [30] [29]. For RNA-seq data, some duplication is expected due to varying transcript abundances, but excessive duplication may indicate low library complexity or over-amplification [30] [29]. Understanding these metrics is essential for correctly interpreting FastQC reports and making informed decisions about data processing.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential tools and materials for RNA-seq quality control

| Item | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality control tool for raw sequencing data | Analyzes FASTQ files; provides metrics on quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, sequence duplication [31] [27] |

| MultiQC | Aggregate QC reports | Summarizes results from FastQC and other tools across multiple samples into a single HTML report [28] [29] |

| RNA-seq Data | Input raw sequencing files | Typically in FASTQ format (compressed: .fastq.gz); contains sequence reads and quality scores [27] |

| Computing Resources | Hardware for analysis | Linux environment; ≥32GB RAM for larger genomes; ≥1TB storage; grid cluster for parallel processing [27] |

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive quality control workflow for RNA-seq data, from raw sequencing reads to aggregated quality assessment:

FastQC Analysis Protocol

Step 1: Load Required Modules and Run FastQC On a computing cluster with bioinformatics tools pre-installed, begin by loading necessary modules and executing FastQC:

The -o parameter specifies the output directory for FastQC results. FastQC can process BAM, SAM, or FASTQ files in any variant, making it versatile for different stages of RNA-seq analysis [31].

Step 2: Run FastQC on Multiple Samples For studies with multiple samples, process all files efficiently:

This generates individual HTML reports and ZIP files for each sample, containing comprehensive metrics on sequence quality [31].

MultiQC Aggregation Protocol

Step 3: Aggregate Results with MultiQC After generating individual FastQC reports, compile them into a comprehensive summary:

MultiQC automatically scans the specified directory for recognized log files (including FastQC outputs) and generates an interactive HTML report aggregating statistics across all samples [31] [28]. The -n parameter allows custom naming of the output file.

Step 4: Transfer and View Reports For researchers using remote servers, transfer the report to a local machine for viewing:

The HTML report can then be downloaded using file transfer tools like FileZilla and opened in a web browser for interactive exploration of the results [30] [28].

Results Interpretation and Quality Assessment

Interpretation Framework for QC Metrics

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for evaluating key QC metrics and determining appropriate actions:

Key Metrics and Acceptance Criteria

Table 2: FastQC metric interpretation guidelines for RNA-seq data

| Metric | Optimal Result | Warning Signs | Potential Causes | Action Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per-Base Sequence Quality | Quality scores mostly in green zone (>Q28); minimal decrease at read ends [27] | Scores drop below Q20 (orange/red); significant quality decrease at ends | Sequencing chemistry degradation; poor cluster detection | Proceed with trimming of low-quality bases [27] |

| Adapter Content | <1% adapter contamination across all positions [27] | >5% adapter content, especially at read ends | Short insert sizes; adapter dimer contamination | Trim adapter sequences before alignment [27] |

| GC Content | Approximately organism-specific % (e.g., ~40-60% for mouse/human); normal distribution shape [29] | Bimodal distribution; significant deviation from expected % | Contamination; sequencing artifacts; library preparation bias | Investigate potential contamination sources [29] |

| Sequence Duplication | Moderate duplication expected for highly expressed genes [30] | >50% duplication in non-ribosomal reads | Low library complexity; PCR over-amplification; insufficient sequencing depth | Evaluate library preparation; consider increasing sequencing depth [30] |

MultiQC Report Navigation

The MultiQC report provides an interactive interface for comparing samples. The "General Statistics" table offers a quick overview of key metrics across all samples, including total sequences, percentage of duplicates, and overall mean quality scores [28] [29]. Configure columns using the "Configure Columns" button to display the most relevant metrics for your experiment. The toolbox on the right enables sample highlighting, renaming, and plot customization for enhanced data exploration and presentation [28].

Status checks are color-coded: green (PASS), orange (WARN), and red (FAIL). For RNA-seq data, some warnings may be expected due to the nature of transcriptomic data, such as sequence duplication from highly expressed genes [30]. The end of the report contains a heatmap summary of all modules, providing a rapid visual assessment of potential problem areas across samples [28].

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

Common Issues and Solutions

- High adapter content: This indicates that a significant proportion of reads contain adapter sequences, requiring trimming before alignment. Use tools like Trimmomatic with appropriate adapter files [27].

- Low-quality scores: Poor quality, particularly at the 3' end of reads, may necessitate more stringent quality trimming. Re-run FastQC after trimming to verify improvement [27].

- Abnormal GC content: Unexpected GC distributions may indicate contamination or technical artifacts. Compare with expected organism-specific GC content and investigate potential sources of contamination [29].

- High duplication levels: While some duplication is normal in RNA-seq due to highly expressed transcripts, excessive duplication may indicate low library complexity. Consider whether the sequencing depth is sufficient for your experimental goals [30] [29].

Installation and Implementation Notes

MultiQC can be installed through multiple package managers: pip install multiqc for PyPI, conda install multiqc for Conda, or via Docker/Singularity containers for reproducible environments [32]. When running MultiQC on a computing cluster, ensure all output files from various tools (FastQC, STAR, etc.) are accessible in the directory structure for comprehensive aggregation [31] [29]. For large studies with multiple analysis steps, MultiQC can incorporate outputs from alignment tools (e.g., STAR), quantification tools (e.g., featureCounts), and others, providing a complete overview of the entire RNA-seq workflow [31] [29].

When interpreting results, researchers should consider that some FastQC warnings may be expected for specific RNA-seq protocols. For example, uneven coverage or sequence duplication is common in transcriptomic data due to varying transcript abundance [30]. The critical assessment involves comparing metrics across all samples to identify outliers rather than focusing solely on absolute values of individual samples.

Within the comprehensive workflow of RNA-seq data analysis, the step of trimming and adapter removal is a critical preprocessing stage that directly impacts the quality and reliability of all subsequent results, from read alignment to the identification of differentially expressed genes [33]. This procedure cleans raw sequencing reads by removing technical sequences such as adapters and low-quality bases, which, if left in the data, can lead to misalignment and inaccurate quantification of gene expression [34] [35]. Among the numerous tools available, Trimmomatic and fastp have emerged as widely adopted solutions. The choice between them influences not only the accuracy of the cleaned data but also the efficiency of the analytical process, requiring researchers to balance factors such as processing speed, ease of use, and the robustness of adapter detection [36] [10]. This protocol details the methodologies for both tools, providing a comparative framework to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal approach for their specific research context.

Tool Comparison and Selection Guide

The decision to use either Trimmomatic or fastp depends on the specific experimental needs, computational resources, and expertise of the researcher. The following table provides a structured comparison to inform this selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Trimmomatic and fastp

| Feature | Trimmomatic | fastp |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Proven reliability; highly customizable trimming [10] [37] | Ultrafast speed; integrated quality control and reporting [38] [10] |

| Speed | Moderate | Very high; designed for all-in-one ultrafast processing [38] |

| Ease of Use | Requires manual specification of parameters like quality score format (Phred33/Phred64) [36] | Simplified operation; automatic adapter detection [36] [38] |

| Adapter Handling | Manual specification of adapter sequences typically required | Automatically detects and removes adapter sequences [38] [35] |

| Quality Control | Requires use of separate tools (e.g., FastQC) for QC [10] | Built-in, comprehensive QC with HTML/JSON reports [38] |

| Error Handling | Strict; can fail with corrupted or truncated files [36] | Flexible and robust to file issues [36] |

| PolyG Trimming | Not a standard feature | Specifically handles polyG tails common in NovaSeq/NextSeq data [38] [35] |

The following decision pathway provides a visual guide for selecting the appropriate tool based on project requirements.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Trimmomatic

Trimmomatic is a precise and flexible trimming tool that allows for detailed control over the trimming process. Its sliding-window approach is effective for the systematic removal of low-quality bases [10].

Detailed Methodology

- Load the Module: On systems using environment modules, load Trimmomatic.

- Create Output Directory: Organize your workspace by creating a dedicated folder for the trimmed outputs.

- Execute Trimmomatic: The following command demonstrates a typical processing run for paired-end reads. The

ILLUMINACLIPparameter is crucial for adapter removal and requires the user to specify the adapter sequence file. To process multiple samples efficiently, this command can be integrated with GNUparallel[39].

Parameter Explanation

Table 2: Key Trimmomatic Parameters and Functions

| Parameter | Function |

|---|---|

PE / SE |

Specifies Paired-End or Single-End input data. |

-threads 4 |

Number of CPU threads to use for faster processing. |

-phred33 |

Specifies the encoding of quality scores. Must be manually set correctly [36]. |

ILLUMINACLIP:<file>:2:30:10 |

Removes adapter sequences; 2=seed mismatches, 30=palindrome threshold, 10=simple clip threshold. |

LEADING:3 |

Removes bases from the start of the read if quality below 3. |

TRAILING:3 |

Removes bases from the end of the read if quality below 3. |

SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 |

Scans the read with a 4-base window, cutting when the average quality per base drops below 15. |

MINLEN:36 |

Discards any read shorter than 36 bases after trimming. |

Protocol for fastp

fastp is an ultra-fast all-in-one tool that simplifies the trimming process by integrating quality control, adapter removal (with auto-detection), and filtering into a single step [38].

Detailed Methodology

- Acquire fastp: fastp can be installed via Conda or by downloading the precompiled binary.

- Create a Working Directory:

- Execute fastp: The command below runs trimming, filtering, and quality control simultaneously. Adapters are detected automatically, and a comprehensive HTML report is generated.

The

--threadparameter allows specification of multiple threads to leverage fastp's high-speed performance [38].

Parameter Explanation

Table 3: Key fastp Parameters and Functions

| Parameter | Function |

|---|---|

--in1, --in2 |

Input read 1 and read 2 FASTQ files (gzip compressed accepted). |

--out1, --out2 |

Output filenames for paired-end reads after filtering. |

--length_required 50 |

Discards reads shorter than 50 bp after trimming [35]. |

--detect_adapter_for_pe |

Enables automatic adapter detection for paired-end reads [38]. |

--poly_g_min_len 10 |

Trims polyG tails of length >=10, essential for NovaSeq/NextSeq data [38] [35]. |

--html, --json |

Generates quality control reports in HTML and JSON format. |

--correction |

Enables base correction for overlapped regions in paired-end reads. |

--thread 8 |

Number of worker threads for parallel computing (enhances speed). |

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section lists the essential computational reagents and their functions required to execute the trimming protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Read Trimming

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Raw FASTQ Files | The primary input data containing the raw nucleotide sequences and their quality scores. | Output from sequencer. |

| Adapter Sequence File | A FASTA file containing adapter sequences used in library preparation (critical for Trimmomatic's ILLUMINACLIP). |

Included with Trimmomatic or available from kit manufacturer. |

| Reference Genome | Not used in the trimming step itself, but is essential for the subsequent alignment step. | Public databases (e.g., ENSEMBL, UCSC). |

| Trimmomatic JAR File | The executable Java ARchive file required to run the Trimmomatic tool. | https://github.com/usadellab/Trimmomatic |

| fastp Binary | The precompiled executable for the fastp software. | https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp |

Post-Trimming Quality Assessment

After executing either trimming protocol, it is imperative to validate the success of the procedure by running a quality control check on the trimmed FASTQ files. Tools like FastQC and MultiQC should be used for this purpose [33] [39].

The MultiQC report should be scrutinized to confirm the successful removal of adapter sequences, the restoration of balanced base composition across read positions, and the overall high quality of the retained reads. This verified, high-quality data is now prepared for the next stage in the RNA-seq workflow: alignment to a reference genome [33].

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, read alignment is a critical step that involves determining the genomic origins of the millions of short sequences (reads) generated by high-throughput sequencers [33]. This process involves mapping these reads to a reference genome, which subsequently enables transcript identification and quantification of gene expression levels [18]. The complexity of eukaryotic transcriptomes, characterized by spliced transcripts where exons may be separated by large introns, necessitates the use of specialized 'splice-aware' aligners rather than standard DNA sequence aligners [40].

Two of the most predominant and powerful tools developed to meet this challenge are STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) and HISAT2 (Hierarchical Indexing for Spliced Alignment of Transcripts 2) [41]. The selection between these aligners can significantly influence downstream results, including the identification of differentially expressed genes, as they employ distinct algorithmic strategies for mapping [41]. This protocol provides a detailed, practical guide for performing read alignment with both STAR and HISAT2, framed within the broader context of an RNA-seq data analysis workflow.

STAR and HISAT2 utilize fundamentally different approaches to solve the problem of spliced alignment, which leads to differences in their computational performance and output characteristics.

STAR's Alignment Strategy: STAR employs a two-step process that is both efficient and sensitive [40]:

- Seed Searching: For each read, STAR searches for the longest sequence that exactly matches one or more locations on the reference genome, known as the Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP). The first MMP is designated seed1. STAR then searches the unmapped portion of the read for the next longest MMP (seed2), and this process continues sequentially [40].

- Clustering, Stitching, and Scoring: The separate seeds are clustered together based on proximity to non-multi-mapping "anchor" seeds. These seeds are then stitched into a complete alignment for the read, with scoring based on user-defined penalties for mismatches, insertions, and deletions [40].

HISAT2's Alignment Strategy: HISAT2 builds upon the Bowtie2 algorithm and uses a sophisticated indexing scheme [42] [41]:

- Hierarchical Graph FM Index (HGFM): HISAT2 uses a small set of global whole-genome FM indices to anchor alignments initially.

- Local Indexing: For alignment extension, especially across splicing events, HISAT2 utilizes a large collection of over 50,000 small local FM indexes that collectively cover the entire genome. This hierarchical approach allows it to rapidly and accurately identify splice sites [42].

The table below summarizes the core algorithmic differences and performance considerations.

Table 1: Comparison of the STAR and HISAT2 Aligners

| Feature | STAR | HISAT2 |

|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Sequential Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) search | Hierarchical Graph FM Index (HGFM) |

| Indexing Strategy | Single, genome-wide index | Global FM-index + ~55,000 local indexes |

| Speed | Very fast [40] | Fast [42] |

| Memory Usage | High (requires ~32GB RAM for human genome) [40] | Moderate (lower than STAR) [42] |

| Key Strength | High accuracy and sensitivity for splice junctions [41] | Efficient use of resources; sensitive mapping for a wide range of reads [42] |

| Typical Use Case | Ideal for projects where computational resources are less constrained and high splice junction accuracy is paramount. | Excellent for standard differential expression analysis and environments with limited memory. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Alignment with STAR

STAR is known for its high accuracy and is particularly effective in clinical research settings, such as with FFPE samples, where precise alignment is critical [41].

1. Generate Genome Index (First-Time Setup)

- Objective: Create a genome index for efficient read mapping.

- Command:

- Parameters Explained:

--runThreadN 6: Number of CPU threads to use.--runMode genomeGenerate: Instructs STAR to build an index.--genomeDir: Path to the directory where the index will be stored.--genomeFastaFiles: Path to the reference genome FASTA file.--sjdbGTFfile: Path to the annotation file (GTF) for splice junction information.--sjdbOverhang 99: Specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions. This should be set toReadLength - 1[40].

2. Align Reads

- Objective: Map sequencing reads from a FASTQ file to the reference genome.

- Command:

- Parameters Explained:

--readFilesIn: Input FASTQ file(s). For paired-end reads, provide two files separated by a comma.--outFileNamePrefix: Path and prefix for all output files.--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate: Output aligned reads as a BAM file, sorted by genomic coordinate, which is the required input for many downstream tools.--outSAMunmapped Within: Keep information about unmapped reads within the final BAM file.--outSAMattributes Standard: Include a standard set of alignment attributes in the output [40].

Protocol B: Alignment with HISAT2

HISAT2 is a robust and memory-efficient aligner, suitable for a wide array of RNA-seq studies [42].

1. Generate Genome Index (First-Time Setup)

- Objective: Build a hierarchical index for the reference genome.

- Command:

- Parameters Explained:

-p 6: Number of threads to use for indexing.genome.fa: The input reference genome FASTA file.genome_index: The basename for the generated index files [42].

2. Align Reads

- Objective: Map sequencing reads to the reference using the pre-built index.

- Command:

- Parameters Explained:

3. Post-Processing: Convert SAM to BAM and Sort

- The SAM output is a large text file. Converting it to a sorted BAM file (binary format) saves space and is required for downstream analysis.

- Command:

This section lists the critical data files and software tools required to execute the read alignment protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Read Alignment

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The DNA sequence of the target organism against which reads are mapped. | Human genome: GRCh38 (hg38) from ENSEMBL or UCSC. |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | File containing genomic coordinates of known genes, transcripts, exons, and splice sites. | Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.92.gtf from ENSEMBL [40]. |

| Raw Sequencing Data (FASTQ) | The input data containing the raw nucleotide sequences and their quality scores. | Files typically with .fq or .fastq extensions. |

| STAR Aligner Software | The splice-aware aligner that uses the sequential MMP algorithm. | Available from https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR [40]. |