Troubleshooting NGS Data Quality: A Comprehensive Guide from QC to Clinical Standards

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for identifying, troubleshooting, and resolving next-generation sequencing (NGS) data quality issues.

Troubleshooting NGS Data Quality: A Comprehensive Guide from QC to Clinical Standards

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for identifying, troubleshooting, and resolving next-generation sequencing (NGS) data quality issues. Covering the entire workflow from foundational concepts to clinical validation, it explores core quality metrics, practical application of QC tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic, strategic solutions for common problems like adapter contamination and low-quality reads, and the evolving landscape of quality standards and regulatory requirements. The article synthesizes current methodologies and best practices to ensure data integrity for reliable downstream analysis in both research and clinical settings.

Understanding NGS Data Quality: Core Metrics and Common Pitfalls

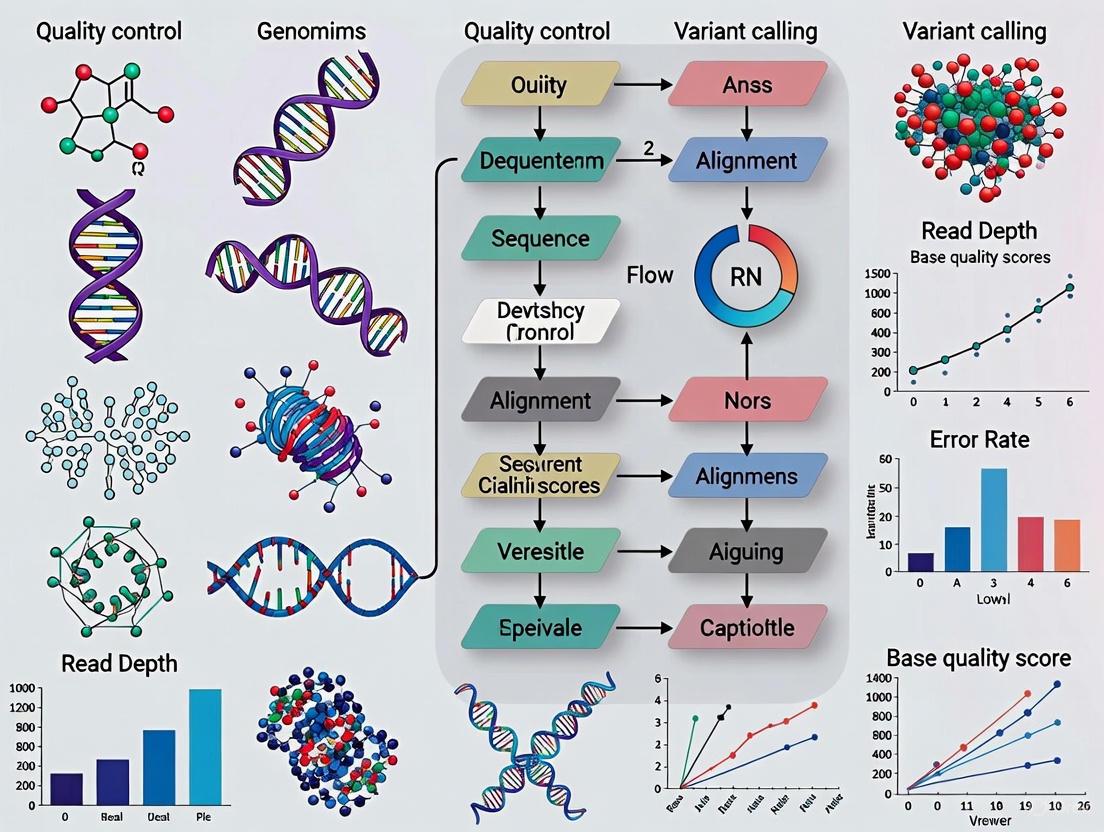

Essential NGS Workflow Steps and Critical Quality Control Checkpoints

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics by enabling the parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, providing unprecedented insights into genetic variations, gene expression, and epigenetic modifications [1]. The transition of NGS from research to clinical and public health settings introduces complex challenges, including stringent quality control criteria, intricate library preparation, evolving bioinformatics tools, and the need for a proficient workforce [2]. A single misstep in the workflow can lead to failed sequencing runs, biased data, and wasted resources, underscoring the critical need for robust troubleshooting frameworks [3]. This guide details the essential steps of the NGS workflow and provides targeted troubleshooting advice to help researchers and clinicians identify, diagnose, and resolve common data quality issues.

The Core NGS Workflow

The standard NGS workflow consists of four fundamental steps: nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis [4] [5]. Understanding each stage is crucial for effective troubleshooting.

Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction

The process begins with the isolation of genetic material (DNA or RNA) from various biological samples such as blood, tissue, cultured cells, or biofluids [4] [6]. The success of all subsequent steps hinges on the quality of the isolated nucleic acids.

Critical Parameters:

- Yield: Sufficient quantity (nanograms to micrograms) is required for library preparation, especially from limited samples like single cells or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) [5].

- Purity: Isolated nucleic acids must be free of contaminants like phenol, ethanol, or heparin that can inhibit enzymes in later steps [5].

- Integrity: The nucleic acids should be intact. For RNA, minimizing degradation is paramount [5] [7].

Common Quality Control (QC) Methods:

- UV Spectrophotometry: Assesses purity via A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios. A ratio of ~1.8 is desirable for DNA, and ~2.0 for RNA [4] [7].

- Fluorometric Assays: Provide accurate quantification using dyes like Qubit assays, which are more specific than UV absorbance [4] [3].

- Electrophoresis: Methods like the Agilent TapeStation determine fragment size distribution and generate an RNA Integrity Number (RIN), which is critical for RNA-seq applications [5] [7].

Step 2: Library Preparation

This process converts the purified nucleic acid sample into a sequenceable "library" [4].

Key Sub-steps:

- Fragmentation: DNA or cDNA is fragmented into smaller pieces via physical, enzymatic, or chemical methods to a size suitable for the sequencing platform [8] [5].

- Adapter Ligation: Short, known oligonucleotide sequences (adapters) are ligated to the fragment ends. These allow the fragments to bind to the flow cell and often contain barcodes for multiplexing different samples in a single run [8] [5] [6].

- Amplification: The adapter-ligated fragments are typically amplified by PCR to generate enough material for sequencing [8] [6].

- Library QC and Quantification: Final libraries are quantified using fluorometry or qPCR to ensure optimal loading concentration on the sequencer [5].

Step 3: Sequencing

The prepared library is loaded onto a sequencer, where the nucleotide sequence is determined. Illumina platforms, for example, use sequencing by synthesis (SBS) chemistry with fluorescently-labeled, reversible-terminator nucleotides [4] [5]. The library fragments are first clonally amplified on a flow cell to form clusters, and then bases are incorporated and detected cycle-by-cycle [5].

Step 4: Data Analysis

Bioinformatics tools process the raw sequencing data (reads) into interpretable results [4] [1]. This stage typically involves:

- Primary Analysis: Base calling and generation of sequence reads in FASTQ format.

- Secondary Analysis: Quality control of raw reads, alignment to a reference genome, and variant calling.

- Tertiary Analysis: Biological interpretation, including variant annotation and pathway analysis [5] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected nature of these core steps and the key actions within each phase:

Critical Quality Control Checkpoints

Proactive quality control is essential at every stage to prevent costly sequencing failures and ensure data integrity.

Pre-Sequencing QC Metrics

Before sequencing, specific metrics are assessed on the input sample and the prepared library.

Table 1: Pre-Sequencing Quality Control Metrics

| Checkpoint | Metric | Target/Acceptable Range | Method/Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Sample | Concentration | Application-dependent (ng-µg) | Fluorometry (Qubit) [7] |

| Purity (A260/A280) | DNA: ~1.8, RNA: ~2.0 | UV Spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) [7] | |

| Integrity | RIN > 8 for RNA-seq [7] | Electrophoresis (TapeStation, Bioanalyzer) [5] [7] | |

| Library | Concentration | Platform-dependent | Fluorometry, qPCR [5] |

| Fragment Size Distribution | Platform-dependent (e.g., 200-500bp) | Electrophoresis (TapeStation, Bioanalyzer) [5] [3] | |

| Adapter Dimer Presence | Minimal to none (sharp peak ~70-90bp is problematic) | Electrophoresis [3] |

Post-Sequencing QC Metrics

After a sequencing run, the initial data output is evaluated using various metrics to determine its quality before proceeding with analysis.

Table 2: Post-Sequencing Quality Control Metrics

| Metric | Description | Target/Acceptable Range |

|---|---|---|

| Q Score | Probability of an incorrect base call. Q30 indicates a 1 in 1000 error rate. | Q ≥ 30 is considered good quality [7] |

| Error Rate | Percentage of bases incorrectly called during one cycle. | Varies by platform; should be stable across the run [7] |

| % Bases ≥ Q30 | The proportion of bases with a quality score of 30 or higher. | Typically > 70-80% [7] |

| Cluster Density | Number of clusters per mm² on the flow cell. | Varies by instrument; too high or low reduces data quality [7] |

| % Clusters Passing Filter (PF) | Percentage of clusters that passed purity filtering. | Generally high; a lower PF % is associated with lower yield [7] |

| GC Content | The proportion of G and C bases in the sequence. | Should match the expected distribution for the organism [7] |

Key Tools:

- FastQC: A widely used tool that provides a comprehensive overview of raw sequence data quality, including per-base sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and more [7].

- Trimmomatic, CutAdapt: Tools used to trim low-quality bases and remove adapter sequences from the raw reads based on the QC report, improving downstream analysis accuracy [7] [1].

Troubleshooting Common NGS Issues

This section addresses frequent problems encountered during NGS library preparation and sequencing.

Low Library Yield

Problem: The final concentration of the prepared library is unexpectedly low, risking poor sequencing performance.

Table 3: Causes and Solutions for Low Library Yield

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants (phenol, salts) or degraded nucleic acid. | Re-purify input sample; ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8); use fluorometric quantification [3]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Under-estimating input concentration leads to suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry. | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV absorbance; calibrate pipettes [3]. |

| Fragmentation Inefficiency | Over- or under-fragmentation reduces adapter ligation efficiency. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragment distribution [3]. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio. | Titrate adapter:insert ratio; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; optimize incubation [3]. |

Adapter Contamination in Library

Problem: A significant peak at ~70-90 bp on an electropherogram indicates the presence of adapter dimers, which compete with the target library during sequencing and reduce useful data output [3].

Solutions:

- Optimize Ligation: Titrate the adapter concentration to find the optimal ratio that minimizes dimer formation while maximizing legitimate ligation [3].

- Improve Cleanup: Use bead-based size selection with optimized bead-to-sample ratios to effectively remove short adapter dimers [3]. Ensure purification steps are performed correctly to avoid carryover.

- Use Pre-validated Kits: Select library preparation kits known for low adapter-dimer formation.

High Duplication Rates

Problem: A high percentage of PCR duplicates in the sequencing data, indicating low library complexity. This leads to uneven coverage and reduces the effective sequencing depth [6].

Solutions:

- Reduce PCR Cycles: Minimize the number of amplification cycles during library prep to prevent over-amplification of a small subset of original fragments [3].

- Increase Input DNA: Use more starting material if possible to increase the initial diversity of fragments.

- Use High-Fidelity Enzymes: Employ polymerases designed to minimize amplification bias [6].

- Bioinformatic Removal: Use tools like Picard MarkDuplicates or SAMTools to identify and remove duplicates in silico during data analysis [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My sequencing run produced a "Low Cluster Density" alert. What does this mean and how can I fix it? A: Low cluster density means an insufficient number of library fragments were bound and amplified on the flow cell. This is often due to inaccurate library quantification. Fluorometric methods can overestimate concentration if adapter dimers are present. For the most accurate results, use qPCR-based quantification for your libraries, as it specifically measures amplifiable molecules. Ensure your library is free of adapter dimers and other contaminants before loading [7] [3].

Q2: Why does my per-base sequence quality drop towards the 3' end of my reads? A: This is a common phenomenon in Illumina sequencing. As the sequencing cycle progresses, the efficiency of nucleotide incorporation, cleavage, and fluorescence detection can decline, leading to a gradual increase in phasing and prephasing and a corresponding drop in quality. This is a characteristic of the technology. The solution is to trim the low-quality 3' ends of your reads using tools like Trimmomatic or CutAdapt before alignment to improve mapping accuracy [7].

Q3: My DNA sample is from an FFPE tissue block. What special considerations should I take? A: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples often contain fragmented and cross-linked DNA. For successful NGS:

- Use extraction methods or kits specifically validated for FFPE samples to maximize yield and quality [5].

- Be aware that your starting DNA will already be fragmented, so adjust your library preparation protocol accordingly.

- Expect lower library complexity and potentially higher duplication rates. Consider using library prep kits designed for damaged DNA to improve results [5].

Q4: What are the key regulatory and quality considerations for implementing NGS in a clinical setting? A: Clinical NGS must meet stringent standards. Key considerations include:

- CLIA Certification: Laboratories producing clinical results must comply with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments [9] [2].

- Assay Validation: Extensive and complex validation of the entire NGS workflow (wet-lab and bioinformatics) is required to ensure accuracy, precision, and reliability [2].

- Quality Management System (QMS): Implementing a robust QMS is essential for continual improvement and proper document management [2].

- Proficiency Testing and Personnel Competency: Staff must be properly trained and assessed, as retaining proficient personnel is a known challenge [2]. Resources like the CDC/APHL NGS Quality Initiative (NGS QI) provide tools and guidance for clinical laboratories [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Tools for NGS Workflows

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA/RNA from various sample types (tissue, blood, cells). | Select kits validated for your sample type (e.g., FFPE, single-cell) [5] [6]. |

| Fluorometric Quantitation Kits (Qubit) | Accurately quantify specific nucleic acid types (dsDNA, RNA). | More specific than UV spectrophotometry; essential for library quantification [7] [3]. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment, end-repair, A-tail, and ligate adapters to nucleic acids. | Platform-specific (Illumina, Ion Torrent); choose based on application (WGS, RNA-seq, targeted) [5] [6]. |

| SPRIselect Beads | Perform size selection and clean-up of nucleic acids during library prep. | Bead-to-sample ratio determines the size range selected; critical for removing adapter dimers [3]. |

| qPCR Quantification Kits (Library Quant) | Precisely quantify amplifiable sequencing libraries. | The gold standard for loading concentration; avoids under- or over-clustering [5]. |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation Kits | Analyze size distribution and integrity of nucleic acids and final libraries. | Essential QC before sequencing to check for adapter dimers and confirm fragment size [5] [7]. |

| FastQC | Quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. | First step in bioinformatics analysis; provides a visual report on raw data quality [7]. |

| Trimmomatic/CutAdapt | Remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences from raw reads. | Used for read trimming and filtering to improve data quality before alignment [7] [1]. |

This guide provides a foundational understanding of key quality metrics in FASTQ files, the standard output from Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms. Proper interpretation of these metrics is a critical first step in troubleshooting NGS data quality issues, ensuring the reliability of downstream analyses in genomics research and drug development.

What is a FASTQ File?

A FASTQ file stores both the nucleotide sequences and the quality information for each base call generated by an NGS instrument [10]. Each sequence read is represented by four lines:

- Line 1 (Header): Begins with

@and contains unique identifier information about the read. - Line 2 (Sequence): The actual nucleotide sequence (A, T, C, G).

- Line 3 (Separator): Begins with a

+and may optionally repeat the header information. - Line 4 (Quality String): A string of characters representing the quality score for each base in Line 2 [10] [11].

What are Base Quality Scores (Q-scores)?

The quality score for each base, also known as a Q-score, is a logarithmic value that represents the probability that a base was called incorrectly by the sequencer [12]. The score is calculated as:

Q = -10 × log₁₀(P)

where P is the estimated probability of an erroneous base call [10] [12]. This score is encoded using a specific ASCII character in the FASTQ file. The most common encoding standard for Illumina data since mid-2011 is Phred+33 (fastqsanger) [10]. The table below shows the relationship between the Q-score, error probability, and base call accuracy.

Table 1: Interpretation of Phred Quality Scores

| Quality Score | Probability of Incorrect Base Call | Base Call Accuracy | Typical ASCII (Phred+33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q10 | 1 in 10 | 90% | + |

| Q20 | 1 in 100 | 99% | 5 |

| Q30 | 1 in 1,000 | 99.9% | ? |

| Q40 | 1 in 10,000 | 99.99% | I |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What do the "Warn" and "Fail" flags in my FastQC report mean, and should I be concerned?

The "Warn" (yellow) and "Fail" (red) flags in a FastQC report are automated alerts that a specific metric deviates from what is considered "typical" for a high-quality, diverse whole-genome shotgun DNA library [13]. They should not be taken as absolute indicators of a failed experiment.

- Context is Critical: These flags are based on generic thresholds and do not account for legitimate biases introduced by specific library preparation methods. It is common and expected for certain experiment types, such as RNA-Seq, bisulfite-seq, or amplicon sequencing, to trigger warnings or failures for specific modules like "Per base sequence content" or "Sequence duplication levels" [13] [10].

- Actionable Advice: Treat these flags as a guide for which modules to investigate more closely. A "Fail" does not mean your data is unusable, but it does mean you must interpret the underlying plot and determine if the result is biologically expected for your experiment type.

My "Per base sequence quality" plot shows a drop in quality at the ends of reads. Is this normal?

A gradual decrease in base quality towards the 3' end of reads is a common and expected phenomenon in Illumina sequencing [10]. This occurs due to two main technical processes:

- Signal Decay: The fluorescent signal intensity decays over successive sequencing cycles, leading to decreased confidence in base calling in later cycles [10].

- Phasing/Prephasing: A loss of synchrony within the cluster of DNA strands being sequenced, causing the signal to blur and quality scores to drop [10].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Per-Base Sequence Quality

| Quality Profile | Likely Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual quality drop towards the 3' end | Expected signal decay or phasing | Proceed with analysis; consider quality trimming for downstream applications. |

| Sudden, severe drop in quality across the entire read or at a specific position | Potential instrumentation breakdown or flow cell issue [10] | Contact your sequencing facility for investigation. |

| Consistently low quality scores across all positions | Overclustering on the flow cell [10] | Consult with your sequencing facility on optimal loading concentrations for future runs. |

Why does my RNA-Seq data "fail" the "Per base sequence content" module?

This is one of the most common "false fails" in FastQC and is typically not a cause for concern for RNA-Seq data. The failure occurs because the module expects a nearly equal proportion of A, T, C, and G bases at each position, which is true for randomly fragmented DNA.

However, RNA-Seq libraries are prepared using random hexamer priming during cDNA synthesis. This priming is not perfectly random, leading to a systematic and predictable bias in the nucleotide composition over the first 10-15 bases of the reads [13] [10]. This biased region is a technical artifact of the library prep, not a problem with the sequencing itself.

What does a high level of "Sequence Duplication" indicate, and when is it a problem?

The Sequence Duplication Levels module shows the percentage of reads that are exact duplicates of another read. The interpretation of this metric depends entirely on your experiment:

- Expected High Duplication:

- Problematic High Duplication:

- Whole-Genome Shotgun (WGS) DNA-Seq: In a diverse WGS library, nearly 100% of reads should be unique. High duplication here often indicates PCR over-amplification during library prep, which can misrepresent the true proportions of fragments in your original sample [13]. It can also occur if the sequencing depth is extremely high (>100X genome coverage) [13].

How should I interpret deviations in the "Per sequence GC content" plot?

This plot compares the observed distribution of GC content per read against an idealized theoretical normal distribution.

- A Shifted but Normal-Shaped Distribution: The peak of the distribution does not match the theoretical model. This indicates a systematic bias but may be biologically real if your source DNA/RNA has a non-standard GC content. It is not automatically a failure.

- A Bimodal or Broad Distribution: This often suggests sample contamination, for example, with a different organism that has a distinct GC content [10].

- An Extremely Narrow Distribution: This is expected for libraries with low sequence diversity, such as amplicon or small RNA libraries, where all sequences are very similar [13].

What are the most critical metrics to check first for a quick quality assessment?

For a rapid triage of your FASTQ data, focus on these three key areas:

- Per Base Sequence Quality: Check that the median quality scores are mostly in the green or orange range, with no sudden, severe drops.

- Adapter Content: Determine if adapter sequences are present in a significant fraction of your reads, which would indicate the need for adapter trimming before alignment.

- Overrepresented Sequences: Review the list of sequences that appear in more than 0.1% of the reads to identify potential contaminants (e.g., adapter dimers, ribosomal RNA) [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a standard process for diagnosing and addressing common quality issues identified by FastQC.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for NGS Quality Control

| Item | Function in Quality Control |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) | Provides initial assessment of nucleic acid sample concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio) before library prep [7]. |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Assesses RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and library fragment size distribution, critical for ensuring input material and final library quality [7]. |

| Illumina PhiX Control | Serves as a run quality monitor; a spike-in control to identify issues with the sequencing instrument itself [12]. |

| FastQC Software | The primary tool for comprehensive visual assessment of raw sequencing data quality from FASTQ files [14]. |

| Trimmomatic/Cutadapt | Software tools used to perform quality and adapter trimming on raw FASTQ files to remove low-quality bases and contaminant sequences [7]. |

NGS Quality Control FAQ

What are the most critical steps for preventing poor-quality NGS data? Quality control must be implemented at every stage, from sample collection through data analysis. Key prevention points include: using high-quality starting material, following standardized library preparation protocols, implementing rigorous quality control checks (e.g., FastQC), and using appropriate bioinformatics pipelines with quality-aware variant callers [15] [16]. Establishing standard operating procedures (SOPs) for sample tracking and processing is essential to minimize human error and batch effects [2] [16].

How can I distinguish true low-frequency variants from sequencing errors? True low-frequency variant detection requires both experimental and computational approaches. Use duplex sequencing or unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for PCR errors and sequencing artifacts. Computationally, employ error-suppression algorithms and set appropriate frequency thresholds based on your platform's error profile. Studies show that with proper error suppression, substitution error rates can be reduced to 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁴, enabling detection of variants at 0.1-0.01% frequency in some applications [17]. Cross-validation with orthogonal methods like digital PCR provides additional confirmation [16].

What are the limitations of different error-handling strategies for ambiguous data? Three common strategies each have limitations: "neglection" (discarding ambiguous reads) can cause significant data loss if errors are systematic; "worst-case assumption" often leads to overly conservative interpretations that may exclude patients from beneficial treatments; and "deconvolution with majority vote" becomes computationally expensive with multiple ambiguous positions (complexity increases as 4ᵏ for k ambiguous positions) [18]. For random errors, neglection often performs best, but for systematic errors or when many reads contain ambiguities, deconvolution is preferred [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Sequencing Yield

Problem: Lower than expected number of sequencing reads or cluster density.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause Category | Specific Issue | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Quality | Degraded nucleic acids | Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >8 or DNA DV₂₀₀ >50%; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [16] |

| Library Preparation | Inefficient fragmentation, ligation, or amplification | Verify fragmentation size distribution; ensure proper adapter ligation; optimize PCR cycle number [15] |

| Quantification | Inaccurate library quantification | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than spectrophotometry (NanoDrop); validate with qPCR [16] |

High Error Rates in Specific Sequence Contexts

Problem: Elevated error rates in homopolymer regions, AT/CG-rich regions, or specific sequence motifs.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Error Pattern | Associated Platform | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Homopolymers (6-8+ bp) | Roche/454, Ion Torrent | Use platform-specific homopolymer-aware variant callers; consider SBS platforms [15] |

| AT/CG-rich regions | Illumina | Increase sequencing depth in problematic regions; optimize cluster generation [15] |

| C>A/G>T substitutions | Multiple platforms | Minimize sample oxidation during storage/processing; use fresh antioxidants [17] |

| C>T/G>A substitutions | Multiple platforms | Address cytosine deamination; use uracil-tolerant polymerases in library prep [17] |

Low Alignment Rates

Problem: Low percentage of reads mapping to reference genome.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause Category | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Contamination | Check for high percentage of non-target organism reads | Improve aseptic technique; include negative controls; use taxonomic classification tools (Kraken) [16] |

| Adapter Content | High adapter detection in FastQC | Increase fragment size selection; optimize adapter trimming tools (Trimmomatic, Cutadapt) [19] |

| Reference Mismatch | Check organism and build compatibility | Use correct reference genome version; consider population-specific references [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Pre-Sequencing Quality Control

Purpose: Assess nucleic acid quality and quantity before library preparation to prevent downstream failures.

Materials:

- Qubit fluorometer and appropriate assays (for accurate concentration)

- Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation (for integrity assessment)

- Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop) for contamination check

Procedure:

- Quantity Measurement: Use Qubit with dsDNA HS or RNA HS assay for accurate concentration of precious samples [16]

- Quality Assessment: Run 1 μL of sample on Bioanalyzer to determine RIN (RNA) or DV₂₀₀ (DNA)

- Contamination Check: Use NanoDrop to check 260/280 and 260/230 ratios

- Acceptance Criteria: Proceed only if RIN >8 (RNA), DV₂₀₀ >50% (DNA), 260/280 ≈1.8-2.0, and 260/230 >2.0 [16]

Protocol 2: Post-Sequencing Quality Metric Evaluation

Purpose: Systematically evaluate sequencing run quality to identify potential issues.

Materials:

- FastQC software

- Computing environment with appropriate resources

- Sequencing data in FASTQ format

Procedure:

- Run FastQC:

fastqc *.fq -o output_directory[19] - Interpret Key Metrics:

- Per base sequence quality: Check if quality scores drop at read ends

- Per sequence quality scores: Identify subsets of low-quality reads

- Adapter content: Determine if adapter sequence is present

- Sequence duplication levels: Assess library complexity [19]

- Compare to Expectations: Establish laboratory-specific baselines for each metric

- Trigger Points: Initiate troubleshooting when metrics fall outside established ranges

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Function | Quality Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification with high fidelity | Reduces polymerase-introduced errors during library amplification [15] |

| KAPA HyperPrep Kit | Library preparation | Optimized for minimal bias in AT/CG-rich regions [17] |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect RNA samples | Essential for maintaining RNA integrity during sample processing [16] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Error correction | Tags individual molecules to distinguish biological variants from PCR/sequencing errors [17] |

| Magnetic Beads with Size Selection | Library normalization and sizing | Provides consistent size selection; critical for insert size distribution [8] |

NGS Workflow and Error Sources Diagram

Quantitative Error Profiles by NGS Platform

Table: Platform-Specific Error Characteristics

| Platform | Chemistry | Typical Error Rate | Common Error Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-Synthesis | 0.26%-0.8% [15] | Substitutions in AT/CG-rich regions [15] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor | ~1.78% [15] | Homopolymer indels [15] |

| SOLiD | Sequencing-by-Ligation | ~0.06% [15] | Color space decoding errors |

| Roche/454 | Pyrosequencing | ~1% [15] | Homopolymer length inaccuracies [15] |

Table: Substitution Error Rates by Type

| Substitution Type | Typical Error Rate | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| A>G/T>C | ~10⁻⁴ [17] | Polymerase errors, sequence context |

| C>T/G>A | ~10⁻⁴ [17] | Cytosine deamination, sample age |

| A>C/T>G, C>A/G>T, C>G/G>C | ~10⁻⁵ [17] | Oxidative damage (C>A), polymerase errors |

Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Methodology

Systematic Approach to Data Quality Issues

When facing NGS data quality issues, follow this diagnostic pathway:

NGS Data Troubleshooting Pathway

This troubleshooting guide provides a framework for systematically addressing NGS data quality issues. Implementation of these practices, combined with laboratory-specific validation, will significantly improve data reliability and reproducibility in genomic studies [2] [16].

Quality control is an essential step in any Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflow, allowing researchers to check the integrity and quality of data before proceeding with downstream analysis and interpretation [7]. Among the most widely used tools for this purpose is FastQC, a program designed to spot potential problems in raw read data from high-throughput sequencing [7]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, properly interpreting FastQC reports is crucial for generating reliable, publication-quality data.

This guide focuses on two critical modules within FastQC that frequently generate warnings: Per Base Sequence Quality and Adapter Content. Understanding these metrics allows for informed decisions about necessary corrective actions, such as read trimming or library reconstruction, ultimately saving valuable time and resources in the research pipeline.

Decoding Per Base Sequence Quality Warnings

What is Per Base Sequence Quality?

The Per Base Sequence Quality module provides an overview of the range of quality values across all bases at each position in the FastQ file [20]. It presents this information using a Box-Whisker plot for each base position, where:

- The central red line represents the median value

- The yellow box represents the inter-quartile range (25-75%)

- The upper and lower whiskers represent the 10% and 90% points

- The blue line represents the mean quality [20]

The background of the graph is divided into three colored sections that provide immediate visual feedback: green (very good quality), orange (reasonable quality), and red (poor quality) [20].

Interpretation Guidelines and Quality Thresholds

FastQC uses predefined quality thresholds to generate warnings and failures for the Per Base Sequence Quality module [20] [21]:

Table 1: FastQC Thresholds for Per Base Sequence Quality

| Alert Level | Condition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Warning | Lower quartile for any base is < 10 OR Median for any base is < 25 | Quality issues detected that may require attention |

| Failure | Lower quartile for any base is < 5 OR Median for any base is < 20 | Serious quality problems requiring corrective action |

Quality scores (Q scores) are logarithmic values calculated as Q = -10 × log₁₀(P), where P is the probability that an incorrect base was called [7]. A Q score of 30 (Q30) indicates a 1 in 1,000 chance of an incorrect base call and is generally considered good quality for most sequencing experiments [7].

Common Causes and Troubleshooting Strategies

Expected Quality Degradation: For Illumina sequencing, it is common to observe base calls falling into the orange area towards the end of a read because sequencing chemistry degrades with increasing read length [20]. This is primarily due to:

- Signal decay: Fluorescent signal intensity decays with each cycle due to degrading fluorophores and some strands in the cluster not elongating [22].

- Phasing: As cycles progress, the cluster loses synchronicity due to incomplete removal of 3' terminators and fluorophores or incorporation of nucleotides without effective 3' terminators [22].

Worrisome Quality Patterns: Sudden drops in quality or large percentages of low-quality reads across the read could indicate problems at the sequencing facility, such as overclustering or instrumentation breakdown [22].

Remediation Strategies:

- For general quality degradation: Perform quality trimming where reads are truncated based on their average quality [20].

- For transient quality issues: Consider masking bases during subsequent mapping rather than trimming, which would remove later good sequence [20].

- For libraries with varying read lengths: Check how many sequences triggered the error using the Sequence Length Distribution module before taking action [20].

Figure 1: Troubleshooting workflow for Per Base Sequence Quality warnings

Addressing Adapter Content Warnings

Understanding Adapter Content Metrics

The Adapter Content module performs a specific search for adapter sequences in your library and shows the cumulative percentage of your library which contains these adapter sequences at each position [23]. The plot shows the proportion of your library that has seen each adapter sequence at each position, with percentages increasing as the read length continues since once a sequence is seen in a read, it is counted as being present right through to the end [23].

Interpretation Guidelines and Thresholds

FastQC uses the following thresholds for adapter content [23] [21]:

Table 2: FastQC Thresholds for Adapter Content

| Alert Level | Condition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Warning | Any adapter sequence present in > 5% of all reads | Significant adapter contamination |

| Failure | Any adapter sequence present in > 10% of all reads | High adapter contamination requiring action |

Common Causes and Solutions

Primary Cause: Adapter content warnings are typically triggered when a reasonable proportion of the insert sizes in your library are shorter than the read length [23]. This occurs when the DNA or RNA fragment being sequenced is shorter than the read length, resulting in the adapter sequence being incorporated into the read [7].

Remediation Strategy: Adapter trimming is the standard solution for high adapter content. This doesn't necessarily indicate a problem with your library - it simply means that reads will need to be adapter trimmed before any downstream analysis [23].

Recommended Tools:

- CutAdapt: Can remove unwanted adapter regions from read data [7].

- Trimmomatic: Another popular tool for adapter removal [7].

- Porechop: Specifically designed for Oxford Nanopore data when working with long reads [7].

Advanced Troubleshooting and Integration with Research Workflows

RNA-Seq Specific Considerations

When working with RNA-seq data, certain FastQC warnings require special interpretation:

- Per base sequence content: This module "always gives a FAIL for RNA-seq data" because the first 10-12 bases result from 'random' hexamer priming during library preparation, which is not truly random and enriches particular bases in these initial nucleotides [22].

- Sequence duplication levels: High duplication levels in RNA-seq may indicate a low complexity library, but could also result from highly expressed genes [22]. In the latter case, this may be biologically meaningful rather than technical.

- Overrepresented sequences: While often indicating contamination, in RNA-seq these could represent highly expressed transcripts. BLAST analysis can help determine the identity of concerning sequences [22].

Table 3: Essential Tools for Addressing FASTQC Quality Issues

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CutAdapt [7] | Removes adapter sequences, poly(A) tails, and primers | Short-read sequencing data |

| Trimmomatic [7] | Performs quality trimming and adapter removal | Short-read sequencing data |

| NanoFilt/Chopper [7] | Trims and filters long reads | Oxford Nanopore data |

| Porechop [7] | Removes adapters from long reads | Oxford Nanopore data |

| FastQ Quality Trimmer [7] | Filters reads based on quality thresholds | General quality trimming |

| Nextflow [24] [25] | Workflow system for scalable, reproducible pipelines | Automating QC and analysis |

Implementing a Systematic Quality Control Protocol

Figure 2: Systematic NGS quality control workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My FastQC report shows a warning for Per Base Sequence Quality, but the overall data looks fine. Should I be concerned? A: FastQC warnings should be interpreted as flags for modules to check out rather than definitive indicators of failure [22]. For Per Base Sequence Quality, a warning is triggered if the lower quartile for any base is less than 10 or if the median for any base is less than 25 [20] [21]. Consider the severity and pattern of the quality drop and whether it might impact your specific downstream applications before deciding on corrective actions.

Q2: What level of adapter content is acceptable, and when should I take action? A: While any adapter content above 5% triggers a warning, the threshold for action depends on your specific research goals. For most applications, adapter content below 5% may be tolerable, but content above 10% (which triggers a FastQC failure) generally requires adapter trimming before proceeding with analysis [23] [21].

Q3: Why does my RNA-seq data consistently fail the Per Base Sequence Content module? A: This is expected for RNA-seq data due to the non-random hexamer priming during library preparation that enriches particular bases in the first 10-12 nucleotides [22]. This "failure" can typically be ignored for RNA-seq data, though you should verify that the bias is limited to the beginning of reads.

Q4: What should I do if I detect overrepresented sequences in my FastQC report? A: First, check if FastQC has identified the source of these sequences. If they are adapter or contaminant sequences, trimming or filtering is recommended. If they are not identified, consider BLASTing the sequences to determine their identity [22]. In RNA-seq experiments, overrepresented sequences could represent highly expressed biological entities rather than technical artifacts.

Q5: How can I automate quality control in my high-throughput sequencing pipeline? A: Workflow systems like Nextflow enable scalable and reproducible pipelines that can integrate FastQC and trimming tools [24] [25]. The nf-core community provides pre-built, high-quality pipelines that include comprehensive quality control steps [25].

Effectively navigating FastQC reports, particularly for Per Base Sequence Quality and Adapter Content warnings, is an essential skill for researchers working with NGS data. By understanding the thresholds, common causes, and appropriate remediation strategies outlined in this guide, scientists can make informed decisions about their data quality and implement appropriate corrective measures. This systematic approach to quality control ensures the generation of robust, reliable data for downstream analysis and interpretation, forming a critical foundation for rigorous scientific research in genomics and drug development.

The quality of your Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data is fundamentally determined by the quality of the nucleic acids you input at the start of your workflow. Issues originating from poor starting material can propagate through library preparation and sequencing, leading to costly failed runs, biased data, and unreliable conclusions [7] [26]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you diagnose, resolve, and prevent the most common issues related to nucleic acid purity, integrity, and contamination, ensuring the foundation of your NGS research is solid.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the quality of my starting nucleic acids so critical for NGS success? High-quality starting material is essential because impurities, degradation, or contaminants can severely disrupt the enzymatic reactions (e.g., fragmentation, ligation, amplification) during library preparation [6]. This can lead to low library yield, biased representation of sequences, high duplicate rates, and ultimately, impaired sequencing performance or complete run failure [7] [26]. Sequencing low-quality nucleic acids compromises data reliability.

2. What are the key differences in quality control (QC) for DNA versus RNA? While both require assessments of purity and integrity, the specific metrics and concerns differ, primarily due to RNA's inherent instability.

- DNA: The ideal A260/A280 ratio is approximately 1.8, indicating minimal protein contamination [7] [26]. For integrity, genomic DNA should be intact and high molecular weight, which can be checked via gel electrophoresis or a bioanalyzer [26].

- RNA: The ideal A260/A280 ratio is closer to 2.0 [7] [27]. The gold standard for integrity is the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), which ranges from 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact). A high-quality RNA sample will typically have a RIN > 8 and show sharp ribosomal RNA bands (e.g., 18S and 28S) [27] [28].

3. My sample concentration is low (e.g., cfDNA or FFPE-derived). How can I quantify it accurately? For low-concentration and challenging samples like cell-free DNA (cfDNA) or nucleic acids from FFPE tissue, fluorometric methods are the gold standard over spectrophotometry [29] [30]. Fluorometers (e.g., Qubit) use dyes that specifically bind to DNA or RNA, providing accurate quantification even in the presence of contaminants like salts or proteins that can skew absorbance-based measurements [26] [30]. This specificity prevents overestimation of viable nucleic acid concentration.

4. What are the best practices for preserving RNA integrity after extraction? To preserve RNA integrity and prevent degradation by RNases:

- Extract immediately upon sample collection or use a stabilization solution (e.g., DNA/RNA Shield or TRIzol) to inactivate RNases during temporary storage [27].

- Use sterile, RNase-free filter tips to minimize contamination.

- Store purified RNA at -80°C in single-use aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

The table below summarizes common symptoms, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Nucleic Acid Quality for NGS

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low A260/280 ratio (<1.8 for DNA, <2.0 for RNA) | Protein or phenol contamination from the extraction process [7] [26]. | Repeat the purification step (e.g., ethanol precipitation, use of a clean-up kit) [6]. |

| Low A260/230 ratio (<2.0) | Contamination with salts, carbohydrates, EDTA, or residual chaotropic reagents [26]. | Use a fluorometer for accurate quantification, as it is not affected by these contaminants [29] [30]. Re-purify the sample if necessary. |

| Degraded RNA (low RIN, smeared gel) | RNase activity during handling or improper sample storage [27]. | Use RNase inhibitors, work quickly on ice, and ensure samples are stored at -80°C. Re-extract with fresh reagents if severe. |

| Pseudo-high DNA concentration (via absorbance) | Significant RNA contamination in the DNA sample [26]. | Treat the DNA sample with DNase-free RNase. Use fluorometry for accurate DNA-specific quantification [26]. |

| High-molecular-weight DNA shearing | Overly vigorous pipetting or vortexing during extraction [26]. | Use wide-bore pipette tips and gentle mixing methods. Check extraction protocol for harsh physical disruption steps. |

| Presence of adapter dimers or chimeric fragments in final library | Inefficient library construction, often due to improper adapter ligation or low input DNA [6]. | Optimize the adapter-to-insert ratio during ligation. Use bead-based size selection to remove short fragments post-ligation [7] [6]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Protocol for Spectrophotometric Purity Assessment

This method provides a rapid assessment of sample concentration and purity, ideal for an initial QC check [7] [29].

- Principle: Nucleic acids absorb UV light at 260 nm, while common contaminants absorb at other wavelengths (proteins at 280 nm, salts/organics at 230 nm) [26].

- Procedure:

- Blank the instrument using the same buffer your nucleic acid is eluted in.

- Apply 1-2 µL of sample to the measurement pedestal.

- Record the concentration (ng/µL) and the purity ratios (A260/280 and A260/230).

- Interpretation: For pure DNA, expect A260/280 ~1.8 and A260/230 >2.0. For pure RNA, expect A260/280 ~2.0 and A260/230 >2.0 [7] [27] [26]. Significant deviations suggest contamination.

Protocol for Fluorometric Quantification

This is the recommended method for accurate quantification, especially for low-yield samples or those destined for NGS [29] [26] [30].

- Principle: Fluorescent dyes that bind specifically to DNA or RNA are used. The fluorescence signal is proportional to the concentration of the nucleic acid and is largely unaffected by common contaminants [30].

- Procedure:

- Prepare a working solution by diluting the fluorescent dye in the appropriate buffer.

- Prepare DNA standards according to the kit's instructions.

- Mix each standard and unknown sample with the working solution in a tube or microplate well.

- Incubate for a few minutes (as per kit protocol) to allow dye binding.

- Measure the fluorescence using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) or a microplate reader with fluorescence capabilities [29].

- Generate a standard curve from the standards and calculate the concentration of the unknown samples.

Protocol for RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Assessment

This method provides a standardized score for RNA integrity, crucial for RNA-Seq applications [27] [28].

- Principle: Automated systems (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation) use microfluidics and electrophoresis to separate RNA fragments by size. The software analyzes the electrophoregram, specifically the ribosomal RNA peaks, to assign an RIN score from 1 to 10 [27].

- Procedure:

- Prepare an RNA ladder and your samples according to the specific kit's instructions (e.g., RNA Nano Kit for Bioanalyzer).

- Prime the station, load the gel-dye mix, ladder, and samples onto the chip.

- Run the assay on the instrument.

- The software automatically generates an electrophoregram, a gel-like image, and calculates the RIN for each sample.

- Interpretation: A RIN of 10 represents perfect RNA, while a RIN of 1 indicates completely degraded RNA. For reliable RNA-Seq, a RIN > 8 is generally recommended, though this can vary by application [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid QC

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop, EzDrop) | Provides rapid, reagent-free assessment of nucleic acid concentration and purity (A260/280, A260/230 ratios) [7] [30]. | Initial quality check of DNA or RNA after extraction. |

| Fluorometer & Assay Kits (e.g., Qubit with dsDNA/RNA HS Assay, EzCube) | Enables highly specific and sensitive quantification of DNA or RNA, unaffected by common contaminants [29] [26] [30]. | Accurate quantification of precious, low-concentration, or contaminated samples before NGS library prep. |

| Automated Electrophoresis System (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) | Assesses nucleic acid integrity and size distribution. Provides RIN for RNA and sizing for NGS libraries [27] [26]. | Evaluating RNA quality for RNA-Seq; checking final NGS library size profile. |

| DNA/RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., DNA/RNA Shield, TRIzol) | Inactivate nucleases and preserve nucleic acid integrity from the moment of sample collection [27]. | Preserving tissues, cells, or extracted nucleic acids for long-term storage or shipment. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based Clean-up Kits | Purify nucleic acids by removing contaminants like salts, proteins, and enzymes; also used for size selection [6]. | Post-extraction clean-up; removing primers and adapter dimers after library amplification. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Systems | Provide walk-away, reproducible, and high-throughput isolation of nucleic acids, minimizing cross-contamination and human error [26]. | Processing large sample batches (e.g., in clinical or population-scale studies) to ensure consistent input quality. |

Workflow Diagram: From Sample to Sequencer

The following diagram outlines the critical quality control checkpoints in a typical NGS workflow to ensure the integrity of the starting material.

Practical NGS QC: Tools and Techniques for Data Cleaning

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized biological research and drug development by enabling comprehensive analysis of genomes and transcriptomes. However, the raw sequencing data generated by these technologies invariably contains artifacts that can compromise downstream analyses if not properly addressed. Within the context of troubleshooting NGS data quality issues, the initial data cleaning phase represents perhaps the most critical preventive measure against analytical artifacts. This guide establishes a practical workflow for transforming raw FASTQ files into cleaned reads, framed specifically around common challenges faced by researchers and incorporating targeted troubleshooting methodologies. The integrity of your final results—whether for variant calling, differential expression, or metagenomic classification—depends fundamentally on the quality of these preliminary data processing steps. By systematically addressing quality trimming, adapter contamination, and sequence filtering, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their biological conclusions while minimizing false positives stemming from technical artifacts.

Understanding Raw Sequencing Data and Common Quality Issues

The FASTQ File Format

FASTQ files represent the standard output format for most NGS platforms, containing both nucleotide sequences and their corresponding quality scores. Each sequencing read occupies four lines in the file: (1) a sequence identifier beginning with '@', (2) the nucleotide sequence, (3) a separator line typically containing just a '+' character, and (4) quality scores encoded as ASCII characters [7]. These quality scores (Q scores) follow the Phred scale, where Q = -10log₁₀(P) and P represents the probability of an incorrect base call. A Q score of 30, for instance, indicates a 1 in 1000 chance of an erroneous base call, equivalent to 99.9% accuracy [7]. Modern Illumina sequencers typically use phred33 encoding, where the quality scores begin with the ASCII character '!' representing Q=0 [31].

Multiple technical and biological factors can introduce quality issues into NGS data, necessitating careful cleaning before analysis:

Adapter Contamination: Occurs when DNA fragments are shorter than the read length, resulting in sequencing through the fragment and into the adapter sequences ligated during library preparation [31] [7]. This contamination interferes with mapping algorithms during alignment.

Quality Score Degradation: Sequencing quality typically decreases toward the 3' end of reads due to diminishing signal intensity over sequencing cycles [7]. Bases with low quality scores have higher error rates and can mislead alignment and variant calling.

Chemical Contaminants: Residual substances from sample preparation (phenol, salts, EDTA, or guanidine) can inhibit enzymatic reactions during library preparation, leading to low yields or biased representation [3].

Spike-in Sequences: Control sequences like PhiX for Illumina or DSC for Nanopore are sometimes added to calibrate basecalling but can persist as contaminants in downstream analyses if not removed [32].

Host DNA Contamination: Particularly relevant in microbiome studies or pathogen sequencing, where host genetic material can dominate libraries and reduce coverage of the target organism [32].

Table 1: Common NGS Data Quality Issues and Their Impacts

| Quality Issue | Primary Causes | Impact on Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Adapter Contamination | Short insert sizes relative to read length | False mapping, reduced alignment rates |

| Low Quality Bases | Signal degradation in later sequencing cycles | Increased false positive variant calls |

| PCR Duplicates | Over-amplification during library prep | Skewed coverage and quantification |

| Spike-in Contamination | Intentional addition for quality control | Misassembly, false taxonomic assignment |

| Host DNA Contamination | Inefficient depletion during sample prep | Reduced target sequence coverage |

Implementing a robust cleaning workflow requires specific bioinformatics tools, each designed to address particular aspects of data quality. The following toolkit represents currently recommended solutions for comprehensive NGS data cleaning:

Table 2: Essential Tools for NGS Data Cleaning and Quality Control

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Parameters | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC [7] | Quality assessment and visualization | --nogroup (disables binning for long reads) | Initial quality assessment of raw and cleaned reads |

| Trimmomatic [31] | Adapter removal and quality trimming | ILLUMINACLIP, SLIDINGWINDOW, MINLEN | Flexible trimming of Illumina data |

| Cutadapt [7] | Adapter trimming | -a (adapter sequence), -q (quality threshold) | Precise adapter removal, especially for custom adapters |

| bbduk [32] | k-mer based filtering and trimming | ktrim, k, mink, hdist | Rapid quality and adapter trimming |

| MultiQC [31] | Aggregate multiple QC reports | --filename (output filename) | Summarize all QC results in a single report |

| CLEAN [32] | Decontamination pipeline | --keep (sequences to preserve), min_clip | Removal of spike-ins, host DNA, and other contaminants |

Step-by-Step Workflow: From FASTQ to Cleaned Reads

Initial Quality Assessment with FastQC

Before initiating any cleaning procedures, assess the raw data quality using FastQC. This provides a baseline understanding of potential issues that need addressing:

Examine the resulting HTML report with particular attention to:

- Per Base Sequence Quality: Identify regions with quality scores dropping below Q20 [7]

- Adapter Content: Determine the proportion of reads containing adapter sequences [31]

- Per Sequence Quality Scores: Detect subsets of reads with generally poor quality

- Overrepresented Sequences: Identify contaminants like spike-ins or ribosomal RNA [32]

Adapter Trimming and Quality Filtering with Trimmomatic

Based on the FastQC report, proceed with adapter removal and quality trimming. For paired-end Illumina data, use Trimmomatic with parameters appropriate for your data:

Key Trimmomatic parameters explained:

- ILLUMINACLIP: Specifies adapter sequences to remove (illumina_multiplex.fa), with settings for seed mismatches (2), palindrome clip threshold (30), and simple clip threshold (5) [31]

- SLIDINGWINDOW: Performs quality trimming using a sliding window of 4 bases, removing bases when average quality drops below 20

- MINLEN: Discards reads shorter than 25 bases after trimming, as short sequences may align to multiple genomic locations [31]

Advanced Decontamination with CLEAN

For studies requiring removal of specific contaminants (host DNA, spike-ins, or rRNA), implement the CLEAN pipeline:

CLEAN provides specialized parameters for different contamination scenarios:

- --spikein: Automatically detects and removes platform-specific spike-ins (Illumina PhiX, Nanopore DSC) [32]

- --host_reference: Removes host sequences using a reference genome, crucial for microbiome and pathogen studies [32]

- --keep: Preserves reads mapping to specified sequences even if classified as contaminants, preventing false positive removal

- min_clip: Filters mapped reads by the total length of soft-clipped positions, improving specificity of contaminant identification [32]

Post-Cleaning Quality Verification

After cleaning, verify the effectiveness of your processing by repeating quality assessment:

Compare the pre- and post-cleaning reports to confirm:

- Reduction or elimination of adapter content

- Improved per-base sequence quality, particularly at read ends

- Removal of overrepresented sequences identified as contaminants

- Maintenance of sufficient read length and quantity for downstream analysis

Troubleshooting Common Data Cleaning Challenges

FAQ 1: Why does my data show poor quality scores at the 3' end of reads, and how should I address this?

Issue: Progressive quality decrease toward read ends, with scores dropping below Q20 in later cycles [7].

Solutions:

- Implement sliding window trimming with Trimmomatic:

SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20 - Set a minimum length threshold to discard severely shortened reads:

MINLEN:25[31] - For severe cases, consider truncating reads to a fixed length before alignment, though this reduces overall coverage

Prevention: Review library preparation protocols, particularly amplification cycles and template quality. Consider using library quantification methods that distinguish amplifiable fragments (qPCR) rather than just total DNA (spectrophotometry) [3].

FAQ 2: How do I resolve persistent adapter contamination after running Trimmomatic?

Issue: Adapter content remains elevated in post-cleaning FastQC reports.

Solutions:

- Verify you're using the correct adapter sequences for your library preparation kit

- Adjust Trimmomatic's stringency parameters:

ILLUMINACLIP:references/illumina_multiplex.fa:2:30:10(increases simple clip threshold) - Try multiple trimming tools sequentially (Trimmomatic followed by Cutadapt) with conservative settings

- For stubborn cases, use k-mer based approaches with bbduk which can detect partial adapter matches [32]

Diagnostic: Examine the "Overrepresented Sequences" section in FastQC to identify specific adapter sequences remaining in your data.

FAQ 3: What approaches effectively remove host DNA contamination from microbiome or pathogen sequencing data?

Issue: High percentage of reads aligning to host genome rather than target organism.

Solutions:

- Use CLEAN pipeline with host reference genome:

--host_reference host_genome.fasta[32] - For human contamination, employ the "keep" parameter to preserve target reads that might share similarity:

--keep target_species.fasta - Consider alignment-based filtering with BWA or minimap2, retaining only unmapped reads

- For prospective studies, implement enzymatic host DNA depletion during library preparation

Validation: After host removal, verify that expected microbial or pathogen signatures remain and that removal hasn't disproportionately affected specific taxonomic groups.

FAQ 4: How can I identify and remove spike-in control sequences that weren't properly documented?

Issue: Unexpected sequences in assemblies that trace back to calibration spike-ins.

Solutions:

- Run CLEAN with automatic spike-in detection:

--spikein auto[32] - Manually screen assemblies against known spike-in sequences (PhiX for Illumina, DSC for Nanopore)

- For Nanopore data with DSC contamination, use the

dcs_strictparameter to prevent removal of similar phage sequences

Documentation: Always record whether spike-ins were used during sequencing and which specific controls were employed to facilitate proper removal during analysis.

FAQ 5: Why is my library yield low after cleaning, and how can I improve recovery?

Issue: Excessive read loss during cleaning steps, resulting in insufficient coverage.

Solutions:

- Loosen trimming stringency (e.g., change quality threshold from Q20 to Q15)

- Reduce minimum length requirement (e.g., from 25bp to 20bp) while monitoring potential multi-mapping issues

- Implement size selection during library preparation to reduce adapter-dimer formation

- Optimize bead-based cleanups using precise bead-to-sample ratios to minimize fragment loss [3]

Diagnostic: Check which step is causing the most significant loss by examining read counts after each processing stage.

Quality Control Metrics and Validation

Establishing quantitative benchmarks for successful data cleaning ensures consistency across experiments and enables objective quality assessment. The following metrics represent generally accepted thresholds for high-quality cleaned NGS data:

Table 3: Quality Metrics for Assessing Data Cleaning Effectiveness

| Metric | Threshold | Measurement Tool | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q20 Bases | >85% | FastQC | Proportion of bases with quality score ≥20 |

| Adapter Content | <1% | FastQC | Successful adapter removal |

| Reads Retained | >70% | Read counting | Balance between quality and yield |

| Spike-in Contamination | <0.1% | CLEAN report | Effective removal of control sequences |

| Minimum Read Length | ≥25bp | Trimmomatic log | Prevents multi-mapping of short sequences |

| Host DNA Content | <5% (pathogen studies) | CLEAN report | Effective host depletion |

Workflow Visualization

A methodical approach to NGS data cleaning represents an essential foundation for any subsequent biological interpretation. By implementing the workflow outlined above—systematic quality assessment, targeted adapter trimming, quality-based filtering, and specialized decontamination—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their genomic analyses. The troubleshooting guidelines address common implementation challenges while emphasizing the importance of quantitative quality metrics. As NGS technologies continue to evolve toward longer reads and single-cell resolution, the principles of rigorous quality control and transparent documentation remain constant. Integrating these robust cleaning practices into standardized analytical pipelines ensures that biological conclusions rest upon the most reliable data possible, ultimately strengthening the validity of research findings in both basic science and drug development contexts.

Hands-On with FastQC and MultiQC for Automated Quality Assessment and Report Generation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What should I do if MultiQC does not find any logs for my bioinformatics tool? First, verify that the tool is supported by MultiQC and that it ran properly, generating non-empty output files. Then, ensure that the log files you are trying to analyze are the specific ones the MultiQC module expects by checking its documentation. If everything appears correct, the tool's output format may not be fully supported, and you should consider opening an issue on the MultiQC GitHub page with your log files [33].

Q2: Why does MultiQC report "Not enough samples found," and how can I resolve this? This frequently occurs due to sample name collisions, where multiple files resolve to the same sample name, causing MultiQC to overwrite previous data with the last one seen. To resolve this:

- Run MultiQC with the

-d(debug) and-s(print help) flags to see warnings about clashing names. - Inspect the

multiqc_data/multiqc_sources.txtfile to see which source files were ultimately used for the report [33]. - If you are working with a collection of files in a platform like Galaxy, using the "Flatten collection" operation before running FastQC can ensure all input files have unique names [34].

Q3: Is it normal for some FastQC tests to fail, and can I ignore them? Yes, it is common and sometimes acceptable for certain FastQC modules to generate "FAIL" or "WARN" statuses. The criteria FastQC uses are based on assumptions about random, diverse genomic libraries. Specific library types may naturally violate these assumptions:

- RNA-seq libraries often fail the "Per base sequence content" test due to biased nucleotide composition at the start of reads [35].

- TruSeq RNA-seq libraries will typically fail the "Per base sequence content" due to hexamer priming [35].

- Nextera genomic libraries may fail the "Per base sequence content" due to transposase sequence bias [35]. Always interpret FastQC results in the context of your specific experiment and sample type.

Q4: How can I add a theoretical GC content curve to my FastQC plot in MultiQC? You can configure this in your MultiQC report. MultiQC comes with pre-computed guides for Human (hg38) and Mouse (mm10) genomes and transcriptomes. Add the following to your MultiQC config file, selecting one of the available guides:

Alternatively, you can provide a custom tab-delimited file where the first column is the %GC and the second is the % of the genome, placing it in your analysis directory with "fastqctheoreticalgc" in the filename [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

MultiQC Finds Only a Subset of Samples

Problem: When running MultiQC on a set of files, particularly from paired-end data in a collection, the final report aggregates results into only "forward" and "reverse" samples instead of showing all individual files [34].

Solution: This is primarily a sample naming issue. The solution is to ensure each file has a unique identifier before processing with FastQC.

- For Galaxy Users: Use the "Flatten collection" tool from the Collection Operations on your paired-end collection before running FastQC. This operation renames the files within the collection, giving each a unique name and preventing MultiQC from merging them incorrectly [34].

- For Command-Line Users: Run MultiQC with the

-d(debug) flag to see warnings about clashing sample names. Use the--fn_as_s_nameflag to use the full filename as the sample name, or adjust your pipeline to assign unique sample names to each file [33].

MultiQC Completely Fails to Find Tool Logs

Problem: MultiQC runs but returns "No analysis results found" for a tool that you know generated logs.

Solution: Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify the root cause:

Check File Size Limits: By default, MultiQC skips files larger than 50MB. If your log files are larger, you will see a message like

Ignoring file as too largein the log. Increase the limit in your config:Check Search Depth Limits: MultiQC searches for specific strings only in the first 1000 lines of a file by default. If your log file is concatenated and the key string is beyond this point, the file will be missed. To search the entire file, use:

Resolving Common System Errors

"Locale" Error

- Problem: A

RuntimeErrorabout Python's ASCII encoding environment [33]. - Solution: Set your system locale by adding the following lines to your

~/.bashrcor~/.zshrcfile and restarting your terminal: [33]

"No space left on device" Error

- Problem: MultiQC fails with an

OSError: [Errno 28]because the temporary directory is full [33]. - Solution: Manually set the temp folder to a location with more space using an environment variable:

Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure: NGS Quality Control with FastQC and MultiQC

This protocol describes a consolidated workflow for assessing the quality of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data, from raw FASTQ files to a unified MultiQC report.

Part I: Assessing Raw Sequence Quality with FastQC

- Input: One or more FASTQ files (can be single-end or paired-end).

- Tool: FastQC.

- Execution:

- Command Line: Run

fastqc <input.fastq> -o <output_directory>. - Galaxy Interface: Select the "FastQC" tool and provide your FASTQ file(s) or a collection of files. If using paired-end data in a nested collection, use "Flatten collection" first to ensure unique sample names [34].

- Command Line: Run

- Output: For each input FASTQ file, FastQC generates an HTML report and a directory (often zipped) containing the raw data, including

fastqc_data.txt.

Part II: Aggregating Results with MultiQC

- Input: The output files from FastQC (

fastqc_data.txtor*_fastqc.zipfiles). - Tool: MultiQC.

- Execution:

- Output: MultiQC generates a single HTML report (

multiqc_report.html) that aggregates results from all detected samples and tools, plus a data directory (multiqc_data/) with the underlying structured data.

Interpreting Key FastQC Modules

The following table summarizes the core FastQC modules and how to interpret their results, which are central to the thesis research on NGS data quality.

| FastQC Module | Purpose | Common "FAIL" Causes & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Per-base sequence quality | Assesses the Phred quality score (Q) across all bases. | True problem: Quality degradation at the ends of reads. Action: Consider trimming. |

| Per-base sequence content | Checks the proportion of A, T, C, G at each position. | Expected bias: First 10-15bp of RNA-seq or Nextera libraries due to hexamer/primer bias. Often ignorable [35]. |

| Per sequence GC content | Compares the observed GC distribution to a theoretical normal model. | True problem: Contamination from a different organism. Expected bias: A single sharp peak for amplicon or other low-diversity libraries. |

| Sequence duplication level | Measures the proportion of duplicate sequences. | Expected bias: High duplication in RNA-seq or amplicon datasets where specific sequences are highly abundant. True problem: Over-representation in diverse genomic DNA can indicate low sequencing depth or PCR over-amplification. |

| Kmer Content | Finds sequences of length k (default=7) that are overrepresented. | Can indicate adapter contamination or specific biological sequences. Often fails and requires careful investigation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| FastQC | A quality control tool that takes FASTQ files as input and calculates a series of metrics, producing an interactive HTML report and raw data files for each sample [36]. |

| MultiQC | An aggregation tool that parses the output logs and data files from various bioinformatics tools (like FastQC), summarizing them into a single, unified HTML report [33]. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Preprocessing tools used to "repair" common quality issues identified by FastQC, such as removing low-quality bases (trimming) and adapter sequences [35]. |

| Theoretical GC File | A tab-delimited text file defining the expected GC distribution for a reference genome. When specified in the MultiQC config, it is plotted as a dashed line over the FastQC Per sequence GC content graph for comparison [36]. |

| MultiQC Config File | A YAML-formatted file that allows extensive customization of MultiQC behavior, from increasing file size limits to changing report sections and adding theoretical GC curves [33] [36]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

NGS Quality Control Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the logical pathway for diagnosing and resolving the most common issues encountered when generating a MultiQC report, as detailed in the troubleshooting guides.

Core Concepts: Why and When Adapter Trimming is Crucial

What are sequencing adapters and why do they need to be removed? Sequencing adapters are short, known oligonucleotide sequences ligated to the ends of DNA or RNA fragments during library preparation to enable the sequencing reaction on platforms like Illumina. [38] These adapter sequences are not part of your target biological sample and must be removed from the raw sequencing reads before downstream analysis. If left in place, adapter sequences can lead to misalignment during mapping, reduce the accuracy of variant calling, and cause false positives in differential expression analysis. [39] [38]

What are the common indicators that my data has adapter contamination? Your data likely contains adapter contamination if you observe one or more of the following in your initial quality control reports (e.g., from FastQC):

- Elevated levels of k-mers (short nucleotide sequences) corresponding to known adapter sequences.

- An abnormal increase in sequence duplication levels, as the same adapter sequence may be present in many reads.

- An unusual distribution of GC content across read lengths.

- For paired-end data, you might notice that the forward and reverse reads align perfectly in a "palindromic" manner, indicating the read-through into the adapter on the opposite end. [7] [40]

Tool-Specific Protocols

Trimmomatic: A Detailed Protocol

Trimmomatic is a versatile, command-line tool for preprocessing Illumina data, known for its highly accurate "palindrome" mode for paired-end adapter trimming. [41] [40]

Basic Command Structure For paired-end data, the fundamental command structure is:

For single-end data, use SE mode, specifying one input and one output file. [41]

Key Trimming Steps and Parameters The trimming steps are executed in the order they are provided on the command line. It is recommended to perform adapter clipping as early as possible. [41]

Table: Essential Trimmomatic Trimming Steps

| Step | Purpose | Parameters & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

ILLUMINACLIP |

Cuts adapter and other Illumina-specific sequences. | TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10:2:TrueTruSeq3-PE.fa : Path to adapter FASTA file.2 : Maximum mismatches in seed alignment.30 : Palindrome clip threshold for PE reads.10 : Simple clip threshold for SE reads.2 : Minimum adapter length in palindrome mode.True : Keep both reads after palindrome clipping. [41] [40] |

LEADING |

Removes low-quality bases from the start. | 3 : Remove leading bases with quality below 3. [41] |

TRAILING |

Removes low-quality bases from the end. | 3 : Remove trailing bases with quality below 3. [41] |

SLIDINGWINDOW |

Trims once average quality in a window falls below threshold. | 4:15 : Scan with 4-base window, cut when average quality < 15. [41] |

MINLEN |

Discards reads shorter than specified length. | 36 : Drop any read shorter than 36 bases after all trimming. [41] |

The Palindrome Trimming Method For paired-end data, Trimmomatic employs a highly accurate "palindrome" mode. It aligns the forward and reverse reads, which should be reverse complements. A strong alignment is a reliable indicator that the reads have sequenced through the entire fragment and into the adapter on the other end, allowing Trimmomatic to pinpoint and clip the adapter sequence precisely. [40]

Cutadapt: A Detailed Protocol

Cutadapt is another widely used tool designed to find and remove adapter sequences, primers, and poly-A tails. It is particularly strong in handling single-end data and complex adapter layouts. [42] [43]

Basic Command Structure A typical command for paired-end data with quality and length filtering is:

Key Parameters Explained

Table: Essential Cutadapt Parameters

| Parameter | Purpose | Example & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

-a / -g |

Specifies adapter sequence to trim. | -a A{100} trims a poly-A tail of up to 100 bases. -g is for 5' adapters. [44] |

-j |

Number of CPU cores to use. | -j 10 uses 10 cores for parallel processing. [44] |

-u |

Removes a fixed number of bases from ends. | -u 20 removes 20 bases from the start. -u -3 removes 3 bases from the end. [44] |

-m |