Unlocking Gene Regulation: A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-seq for Transcription Factor Binding Analysis

This article provides a thorough exploration of Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for mapping transcription factor (TF) binding sites genome-wide.

Unlocking Gene Regulation: A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-seq for Transcription Factor Binding Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for mapping transcription factor (TF) binding sites genome-wide. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from protein-DNA cross-linking to sequencing. The scope extends to methodological best practices, including the ENCODE pipeline and quality control metrics, troubleshooting for common experimental and computational challenges, and validation through peak-calling comparisons and Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis. By integrating current standards and emerging tools, this guide serves as a critical resource for robust experimental design and data interpretation in functional genomics and therapeutic discovery.

ChIP-seq Fundamentals: From Principle to Genome-Wide Discovery

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents a cornerstone technique in molecular biology for mapping protein-DNA interactions across the entire genome. At the heart of this methodology lies the process of cross-linking—the covalent stabilization of molecular interactions between proteins and DNA, or between proteins and other proteins within chromatin complexes. This stabilization is crucial for preserving biologically relevant interactions throughout the subsequent experimental procedures, which involve chromatin fragmentation and immunoselection. The resulting data enables researchers to identify transcription factor binding sites, histone modification patterns, and chromatin regulator occupancy, providing fundamental insights into gene regulatory mechanisms [1] [2].

Within the context of a broader thesis on ChIP-seq for transcription factor binding research, understanding cross-linking principles becomes paramount. Transcription factors frequently engage in transient interactions and operate within larger multi-protein complexes that may not directly contact DNA. Standard formaldehyde cross-linking alone often proves insufficient for capturing these complex interactions, leading to the development of dual-crosslinking strategies that significantly improve the mapping of indirect chromatin associations [2]. The choice and optimization of cross-linking protocols directly impact the signal-to-noise ratio, specificity, and overall success of ChIP-seq experiments, making this step a critical determinant in the quality of resulting binding profiles.

Chemical Principles of Cross-Linking

Cross-Linking Reagent Properties and Mechanisms

Protein-DNA cross-linking reagents function by creating covalent bonds between macromolecules in close spatial proximity. These chemical bridges preserve in vivo interactions during the harsh conditions of cell lysis, chromatin fragmentation, and immunoprecipitation. The most common reagents fall into two primary categories: those targeting protein-DNA interactions and those stabilizing protein-protein complexes, differentiated by their chemical properties, spacer arm lengths, and reaction mechanisms [2] [3].

Formaldehyde remains the most widely utilized reagent for direct protein-DNA cross-linking due to its unique properties. This small molecule (with a short ~2Å spacer arm) rapidly penetrates cells and creates reversible cross-links between primary amines in proteins and DNA, primarily through methylene bridges. Its reversibility allows for efficient crosslink reversal during later stages of the protocol, facilitating DNA purification and library preparation. However, its efficiency decreases dramatically for proteins that do not directly contact DNA, as their connection to chromatin may be mediated through larger multi-protein complexes [2].

For challenging targets that indirectly associate with chromatin, dual-crosslinking approaches incorporating bifunctional cross-linkers with longer spacer arms have been developed. These reagents, such as EGS (ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate)) with a 16.1Å spacer arm or DSP (dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate)), primarily react with amine groups—particularly the ε-amino group of lysine residues [2] [3]. Their extended spacer lengths enable them to bridge larger distances within protein complexes, while their cleavable disulfide bonds (in DSP) or other reversible chemistries permit dissociation of cross-linked complexes after immunoprecipitation [3].

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Linking Reagents

Table 1: Properties and Applications of Common Cross-Linking Reagents

| Reagent | Spacer Arm Length | Primary Target | Reversibility | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | ~2Å | Protein-DNA | Acid/heat reversal | Direct DNA binders (TFs, histones) |

| BS³ (Bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate) | 11.4Å | Protein-protein | Non-reversible | Antibody-bead conjugation [4] |

| EGS (Ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate)) | 16.1Å | Protein-protein | Limited reversibility | Dual-crosslinking for indirect chromatin associations [2] |

| DSP (Dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate)) | 12Å | Protein-protein | Reductive cleavage | Protein complex stabilization for weak/transient interactions [3] |

The selection of an appropriate cross-linking strategy depends heavily on the nature of the chromatin-associated protein under investigation. Direct DNA binders such as sequence-specific transcription factors (e.g., REST, CTCF) typically perform well with formaldehyde cross-linking alone [5]. In contrast, chromatin regulators and co-activator complexes that assemble into larger structures often require dual-crosslinking approaches to preserve their genomic associations through multi-protein interfaces [2]. Empirical testing remains the gold standard for determining optimal cross-linking conditions for novel targets.

Experimental Protocols

Standard Formaldehyde Cross-Linking Protocol

The single-crosslinking protocol using formaldehyde serves as the foundation for most transcription factor ChIP-seq experiments. The following protocol, optimized for mammalian cell lines such as HeLa and HepG2, outlines critical steps for effective protein-DNA cross-linking [6]:

Materials Required:

- Cells in culture (1×10⁷ cells per ChIP sample recommended)

- Ice-cold PBS

- 37% formaldehyde stock solution (freshly opened)

- 2.5M Glycine solution (for quenching)

- Cell scrapers (for adherent cells)

Procedure:

- Cell Harvesting: Grow cells to approximately 90% confluence. For adherent cells, gently rinse twice with 10-20mL ice-cold PBS. For suspension cells, pellet at 1,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C and discard supernatant [6].

Cross-Linking: Resuspend cells in PBS containing 1% formaldehyde (freshly diluted from 37% stock). Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation. Critical: Perform this step in a fume hood and use fresh formaldehyde for consistent results [6].

Quenching: Add glycine to a final concentration of 125mM and incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation to quench unreacted formaldehyde [6].

Washing: Pellet cells and wash twice with ice-cold PBS to remove quenching reagents. Cells can now be processed immediately or frozen at -80°C for future use [6].

Dual-Crosslinking Protocol for Indirect Chromatin Associations

For proteins that indirectly interact with DNA, such as chromatin remodelers or transcriptional co-regulators, a dual-crosslinking approach significantly improves recovery. This protocol has been successfully applied for mapping heterochromatin proteins in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and can be adapted for mammalian systems [2]:

Materials Required:

- EGS (ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate)) prepared as 150mM stock in DMSO

- Formaldehyde (37% stock solution)

- PBS (without primary amines)

- Orbital shaker

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash cells twice with PBS to remove any culture media containing primary amines that would compete with the cross-linking reaction [2].

Primary Cross-Linking: Resuspend cell pellet in PBS containing 1.5mM EGS (diluted from 150mM stock). Incubate horizontally on an orbital shaker for 30 minutes at room temperature with low-speed agitation. Critical: Add EGS stock directly to the cell suspension to prevent precipitation on tube walls [2].

Secondary Cross-Linking: Add formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1% directly to the cell suspension without intermediate washing. Incubate for an additional 30 minutes on an orbital shaker [2].

Quenching and Washing: Quench the reaction with 125mM glycine for 5 minutes. Pellet cells and wash twice with ice-cold PBS before proceeding to cell lysis [2].

Antibody-Bead Cross-Linking Protocol

To prevent co-elution of antibody heavy and light chains during ChIP elution steps—which can interfere with downstream applications—cross-linking antibodies to magnetic beads is recommended. This protocol utilizes BS³ (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate), a water-soluble crosslinker that forms stable amide bonds at physiological pH [4]:

Materials Required:

- Dynabeads Protein A or Protein G with immobilized IgG

- BS³ (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate)

- Conjugation Buffer (20mM Sodium Phosphate, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7-9)

- Quenching Buffer (1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5)

- PBST or IP buffer

Procedure:

- BS³ Solution Preparation: Prepare a fresh 100mM BS³ stock in Conjugation Buffer, then dilute to 5mM working concentration (250μL required per sample) [4].

Bead Washing: Wash IgG-coupled Dynabeads twice with 200μL Conjugation Buffer. Place on magnet and discard supernatant [4].

Cross-Linking Reaction: Resuspend beads in 250μL of 5mM BS³ solution. Incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes with tilting or rotation [4].

Quenching: Add 12.5μL Quenching Buffer and incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature with tilting/rotation [4].

Final Washes: Wash cross-linked beads three times with 200μL PBST or IP buffer before proceeding with immunoprecipitation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Linking Reagents | Formaldehyde, EGS, DSP, BS³ | Stabilize protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions; choice depends on target and direct vs. indirect DNA binding [2] [3]. |

| Cell Lysis & Nuclear Extraction Buffers | Nuclear Extraction Buffer 1 (50mM HEPES-NaOH pH=7.5, 140mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% Glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% Triton X-100) [6] | Lyse cells and extract nuclei while preserving cross-linked chromatin complexes. |

| Sonication Buffers | Non-Histone Sonication Buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH=8.0, 100mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5mM EGTA, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% sodium lauroylsarcosine) [6] | Optimize chromatin shearing efficiency; composition varies for histone vs. non-histone targets. |

| Magnetic Beads | Dynabeads Protein A/G [6] | Solid-phase support for antibody-mediated chromatin capture; enable efficient washing and sample recovery. |

| Protease Inhibitors | cOmplete Mini EDTA-free, PhosSTOP [3] | Prevent protein degradation during chromatin preparation and immunoprecipitation steps. |

| ChIP-Grade Antibodies | Target-specific validated antibodies | Specifically enrich for cross-linked chromatin complexes containing protein of interest; require rigorous validation [7]. |

ChIP-seq Data Standards and Quality Control

The ENCODE consortium and other large-scale projects have established comprehensive quality standards for ChIP-seq experiments to ensure data reproducibility and reliability. Adherence to these standards is particularly crucial for transcription factor binding studies where signal-to-noise ratios can be challenging [7].

Experimental Design Standards:

- Biological Replicates: Experiments should include at least two biological replicates to assess reproducibility [7].

- Control Experiments: Each ChIP-seq experiment requires a corresponding input DNA control with matching replicate structure and sequencing parameters [7].

- Antibody Validation: Antibodies must be characterized according to consortium standards, demonstrating specificity for the intended target [7].

Sequencing Depth Requirements:

- Transcription Factors: Minimum of 20 million usable fragments per replicate [7].

- Histone Modifications: 40-50 million reads recommended for human samples, with broader marks (e.g., H3K27me3) requiring greater depth [8].

Quality Metrics:

- Library Complexity: Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) > 0.9; PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients PBC1 > 0.9 and PBC2 > 10 [7].

- Reproducibility: Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis for transcription factor experiments with rescue and self-consistency ratios < 2 [7].

- Enrichment: Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) sufficient for target type (e.g., >1% for transcription factors, >5% for histone marks) [7].

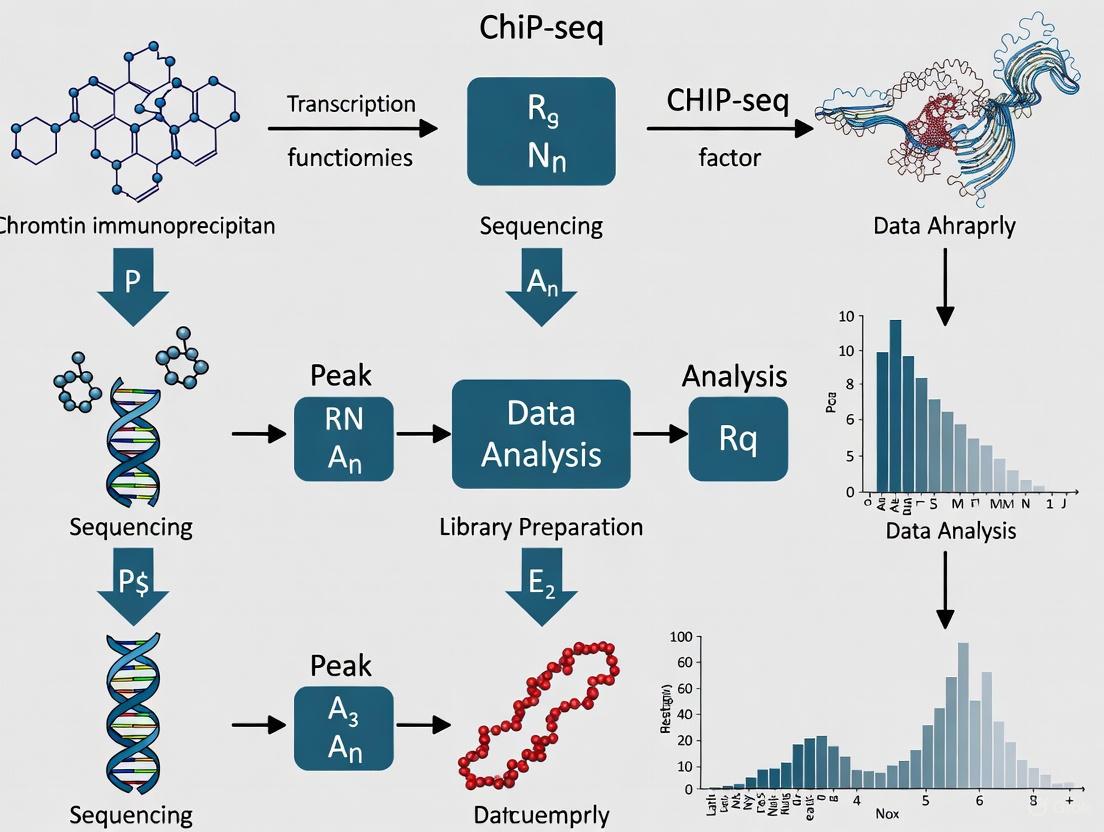

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: ChIP-seq cross-linking workflow for direct and indirect DNA binders.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Successful ChIP-seq experiments require careful optimization of cross-linking conditions. The following guidelines address common challenges:

Cross-Linking Optimization:

- Duration Determination: Test cross-linking times from 5-30 minutes; excessive cross-linking reduces chromatin shearing efficiency and antibody accessibility [6] [2].

- Concentration Titration: Evaluate formaldehyde concentrations from 0.5-2% to balance between sufficient cross-linking and reversible linkage [6].

- Dual-Crosslinker Testing: For recalcitrant targets, empirically test cross-linkers with different spacer arm lengths (EGS: 16.1Å, DSP: 12Å, BS³: 11.4Å) to determine optimal stabilization [2].

Quality Assessment:

- Sonication Efficiency: Verify fragment size distribution (150-300bp for histones, 200-700bp for transcription factors) after chromatin shearing [6].

- Antibody Validation: Include positive control targets with established binding patterns to confirm protocol effectiveness [7].

- Cross-linking Efficiency: For dual-crosslinking approaches, ensure thorough washing with PBS before adding cross-linkers to remove primary amines that would compete with the reaction [2].

Protein-DNA cross-linking represents a fundamental process enabling the precise mapping of transcription factor binding sites and chromatin architecture through ChIP-seq methodologies. The selection of appropriate cross-linking strategies—from standard formaldehyde to dual-crosslinking approaches—directly influences the ability to capture both direct and indirect DNA associations, particularly for complex chromatin regulators. As the field advances with increasingly sensitive detection methods and applications to rare cell populations, optimized cross-linking protocols will continue to play a pivotal role in generating comprehensive maps of the regulatory genome. By adhering to established quality standards and systematically troubleshooting experimental parameters, researchers can ensure the production of high-quality, reproducible data that advances our understanding of gene regulatory mechanisms in health and disease.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a powerful method that allows researchers to capture a snapshot of protein-DNA interactions across the entire genome, providing critical insights into gene regulation, epigenetic mechanisms, and cellular identity [9] [10]. This technique is particularly valuable for transcription factor (TF) binding research, enabling the genome-wide mapping of TF binding sites and revealing the regulatory networks that control gene expression programs in development, health, and disease [9] [11]. The following application note provides a detailed, practical workflow from initial experimental setup through computational analysis, specifically framed within the context of TF binding research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Experimental Workflow: From Cells to Sequencing Library

Step 1: Experimental Design and Controls

A successful ChIP-seq experiment begins with careful planning. For transcription factor studies, biological replicates are essential, with the ENCODE consortium recommending at least two replicates per experiment [7]. Appropriate controls must be included: a "no-antibody control" (mock IP) for each IP, an input DNA sample (sonicated crosslinked chromatin without immunoprecipitation), and known positive and negative genomic regions for validation [12]. Cell number requirements typically range from 500,000 to millions of cells per immunoprecipitation, though recent advancements have enabled ChIP with significantly fewer cells [12] [13].

Step 2: Crosslinking

Crosslinking stabilizes protein-DNA interactions using formaldehyde, which covalently links proteins to DNA in intact living cells [12]. Formaldehyde is a zero-length crosslinker ideal for direct interactions, while longer crosslinkers like EGS (16.1 Å) or DSG (7.7 Å) can trap larger protein complexes [12]. Optimization tip: Crosslinking time must be carefully titrated - insufficient crosslinking reduces target capture, while excessive crosslinking masks epitopes and impedes chromatin shearing [13]. After crosslinking, the reaction is quenched, and cell pellets can be stored at -80°C [12].

Step 3: Cell Lysis and Chromatin Preparation

Cells are lysed using detergent-based lysis solutions to solubilize crosslinked protein-DNA complexes [12]. Protease and phosphatase inhibitors are essential at this stage to maintain complex integrity [12]. The quality of lysis can be monitored microscopically by comparing whole cells versus nuclei [12].

Step 4: Chromatin Shearing

Chromatin is fragmented to mononucleosome-sized pieces (150-300 bp) either mechanically by sonication or enzymatically using micrococcal nuclease (MNase) [12] [13]. Sonication provides randomized fragments, while MNase digestion is more reproducible but has preference for internucleosome regions [12]. Critical optimization: Fragment size dramatically impacts resolution; oversized fragments (>600-700 bp) reduce mapping precision, while excessive fragmentation disrupts target interactions [13]. Shearing efficiency should be verified by agarose gel or capillary electrophoresis before proceeding [13].

Step 5: Immunoprecipitation

Sheared chromatin is incubated with a target-specific antibody. Antibody selection is crucial - monoclonal antibodies offer specificity but may recognize buried epitopes, while polyclonal/oligoclonal antibodies recognize multiple epitopes with potentially higher capture efficiency [12]. For transcription factors, antibody characterization according to ENCODE standards is mandatory [7]. Antibody-bound complexes are recovered using magnetic beads coated with protein-A/G, followed by stringent washes to reduce background [13].

Step 6: DNA Recovery and Library Preparation

Crosslinks are reversed using Proteinase K and heat, followed by DNA purification [13]. The concentration and fragment size distribution of purified DNA should be confirmed before library preparation [13]. For sequencing, DNA undergoes end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification with indexing to allow sample multiplexing [13]. Final libraries are quantified and pooled at equimolar ratios for sequencing [13].

The complete experimental workflow is visualized in the following diagram:

Sequencing Considerations for Transcription Factor Studies

Sequencing depth and strategy must be tailored to the specific research goals. The table below summarizes key sequencing parameters for transcription factor ChIP-seq experiments:

Table 1: Sequencing Requirements for Transcription Factor ChIP-seq

| Parameter | Transcription Factors | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended Read Depth | 20-30 million reads per sample [7] [10] | ENCODE standards require 20 million usable fragments per replicate [7] |

| Read Type | Single-end often adequate [10] | Paired-end provides more information but increases cost and processing time |

| Minimum Read Length | 50 base pairs [7] | Longer read lengths are encouraged for improved mapping |

| Control Samples | Input DNA with matching read type and length [7] | Essential for distinguishing specific enrichment from background |

Computational Analysis Workflow

Step 1: Quality Control and Read Preprocessing

Raw sequencing data must undergo quality assessment using tools like FastQC. Adapters and low-quality bases should be trimmed, with tools like Trim Galore commonly employed [10]. Key quality metrics include per-base sequence quality, sequence duplication levels, and adapter contamination [14].

Step 2: Alignment to Reference Genome

Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using specialized aligners such as Bowtie2, BWA, or SOAP [9] [14]. The ENCODE pipeline requires mapping to standardized genome assemblies and formats [7]. Alignment statistics, including overall mapping rate and duplicate rates, should be documented.

Step 3: Quality Assessment of ChIP Enrichment

For transcription factor studies, several quality metrics must be assessed:

- Strand Cross-Correlation: Calculates Pearson correlation between forward and reverse strand tag densities [5]. Quality datasets show a peak at the predominant fragment length. The Normalized Strand Cross-correlation Coefficient (NSC) and Relative Strand Cross-correlation (RSC) are key metrics [5].

- FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks): Measures enrichment by calculating the proportion of reads falling within peak regions [7]. Higher FRiP scores indicate better enrichment.

- Library Complexity: Assessed via Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF >0.9) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 >0.9, PBC2 >10) [7].

Table 2: Key Quality Metrics for Transcription Factor ChIP-seq

| Quality Metric | Target Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| NSC (Normalized Strand Cross-correlation) | >1.05 [5] | Higher values indicate stronger enrichment |

| RSC (Relative Strand Cross-correlation) | >0.8 [5] | Values <0.5 suggest poor ChIP quality |

| FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) | Varies by target | Higher values indicate better enrichment [7] |

| NRF (Non-Redundant Fraction) | >0.9 [7] | Measures library complexity |

| IDR (Irreproducible Discovery Rate) | Rescue/self-consistency ratios <2 [7] | Measures replicate concordance |

Step 4: Peak Calling and Identification of Binding Sites

Peak calling identifies genomic regions with significant enrichment compared to background. For transcription factors, which typically show punctate binding, MACS2 (Model-Based Analysis of ChIP-Seq) is widely used [9] [14]. The ENCODE TF pipeline uses Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis to identify consistent peaks across replicates, generating conservative and optimal peak sets [7].

Step 5: Downstream Analysis

- Peak Annotation: Associating peaks with genomic features (promoters, enhancers, etc.) using tools like ChIPseeker [14].

- Motif Analysis: Identifying enriched sequence motifs in binding sites using tools like MEME or HOMER [9] [10].

- Differential Binding: Comparing binding patterns across conditions with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [14] [10].

- Integrative Analysis: Correlating binding sites with gene expression data and other functional genomic datasets [15].

The complete computational workflow is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinkers (Formaldehyde, DSG, EGS) | Stabilize protein-DNA interactions | Formaldehyde for direct interactions; longer crosslinkers for complex complexes [12] |

| TF-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of target protein | Must be characterized for ChIP; check ENCODE standards [7] [12] |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Recovery of antibody-bound complexes | More efficient than agarose beads for small sample sizes [12] |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatic chromatin fragmentation | More reproducible than sonication but less random [12] |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitors | Maintain complex integrity during lysis | Essential to prevent degradation of proteins and PTMs [12] |

| DNA Purification Kits | Recovery of pure DNA after reverse crosslinking | Column-based methods provide high purity [13] |

| Library Preparation Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Must be compatible with sequencing platform |

Advanced Applications in Transcription Factor Research

Recent advancements in ChIP-seq methodology and analysis have expanded its applications in TF research. Virtual ChIP-seq approaches can now predict TF binding in new cell types by learning from transcriptomic data and existing ChIP-seq datasets, enabling studies where cell numbers are limiting [15]. Integrative analyses combining TF binding data with chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and gene expression (RNA-seq) can reveal transcriptional regulatory networks [15]. Single-cell ChIP-seq methodologies are emerging to elucidate cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues and cancers [16].

ChIP-seq remains a cornerstone technology for transcription factor binding research, providing genome-wide insights into transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Success requires careful optimization at both wet-lab and computational stages, with particular attention to antibody validation, appropriate controls, and quality assessment metrics. When properly executed, ChIP-seq enables researchers to map transcriptional networks, identify dysregulated binding events in disease, and potentially discover novel therapeutic targets in drug development programs.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has fundamentally transformed our understanding of transcription factor biology by enabling genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions in living cells. This technology provides an unbiased approach to identify transcription factor binding sites with higher resolution, greater coverage, and improved signal-to-noise ratios compared to previous methodologies. By revealing the precise genomic locations where transcription factors bind, ChIP-seq has illuminated complex transcriptional networks, elucidated mechanisms of differential gene regulation, and provided insights into epigenetic modifications that govern cellular identity and function. This application note details the revolutionary impact of ChIP-seq on transcription factor research, provides comprehensive experimental protocols, and synthesizes key quantitative findings that have reshaped our understanding of gene regulatory mechanisms.

Prior to the development of ChIP-seq, researchers relied on techniques with significant limitations for studying transcription factor biology. Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA) and DNase I footprinting provided only in vitro analysis of protein-DNA interactions outside their native chromatin context [9]. ChIP-chip, which combined chromatin immunoprecipitation with DNA microarrays, represented an improvement but suffered from limited dynamic range, lower resolution, and an inability to interrogate repetitive genomic regions due to hybridization constraints [17]. The technological breakthrough came in 2007 when Robertson et al. first developed the ChIP-seq method, applying it to identify signal transducers and activators of transcription 1 (STAT1) targets in human cells and demonstrating its superior coverage and accuracy [9].

ChIP-seq leverages massively parallel DNA sequencing to decode millions of immunoprecipitated DNA fragments simultaneously, providing actual DNA sequences of precipitated fragments rather than hybridization signals [9]. This fundamental advancement provides several revolutionary advantages: (1) unambiguous genome-wide sequence information without prior knowledge of binding sites; (2) higher resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites; (3) a broader dynamic range for quantifying binding strength; and (4) the ability to detect binding events in repetitive genomic regions that were previously masked in array-based approaches [17]. The accumulation of ChIP-seq data through large consortiums like ENCODE and modENCODE has further standardized practices and expanded our knowledge of transcriptional regulatory networks across multiple organisms [18].

Technical Foundations: ChIP-seq Methodology

Core Experimental Workflow

The fundamental ChIP-seq procedure involves specific steps to capture and identify protein-DNA interactions occurring in living cells [19] [9].

Figure 1: ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow. The process begins with formaldehyde cross-linking of living cells to preserve protein-DNA interactions, followed by chromatin fragmentation, targeted immunoprecipitation, and high-throughput sequencing of bound DNA fragments [19] [9] [17].

Critical Reagents and Materials

Successful ChIP-seq experiments require specific, high-quality reagents at each stage of the protocol.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-linking Agents | Formaldehyde (37%), DSG | Preserve transient protein-DNA interactions in their native chromatin context [19] [17] |

| Antibodies | ChIP-grade TF-specific antibodies, Anti-GFP (A-11122), Anti-FLAG (F1804) | Specifically immunoprecipitate target transcription factor; most critical factor for success [19] [18] |

| Immunoprecipitation Beads | Dynabeads Protein G/A | Magnetic beads for efficient antibody-antigen complex capture [19] |

| Chromatin Fragmentation | Bioruptor sonication system, Micrococcal nuclease | Shear chromatin to optimal fragment size (100-300 bp) [19] [17] |

| Library Preparation | DNA purification reagents, Adapters, PCR amplification components | Prepare sequencing library from immunoprecipitated DNA [19] |

Detailed Protocol: Transcription Factor ChIP-seq

The following protocol has been successfully applied to dozens of sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factors, primarily in Arabidopsis but adaptable to other organisms [19]:

Cross-linking: Harvest 1-4 grams of plant tissue or 1-10 million cultured cells and resuspend in fixation buffer containing 1% formaldehyde. Perform vacuum infiltration for 20 minutes (for plant tissues) or incubate for 8-12 minutes (for cultured cells) at room temperature. Quench with 125mM glycine for 5 minutes [19].

Nuclei Isolation: Grind cross-linked samples in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder. Homogenize in Extraction Buffer I and filter through cheesecloth and Miracloth. Centrifuge at 2,880 × g for 20 minutes. Resuspend pellet in Extraction Buffer II and centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes. Further purify through a cushion of Extraction Buffer III by centrifuging at 16,000 × g for 1 hour [19].

Chromatin Shearing: Resuspend nuclei in Nuclei Lysis Buffer and rotate for 20 minutes at 4°C. Sonicate chromatin using a Bioruptor for 25 cycles (30 seconds ON, 2 minutes OFF) at HIGH setting. Centrifuge at maximum speed for 10 minutes and collect supernatant containing sheared chromatin [19].

Immunoprecipitation: Pre-bind 10μg ChIP-grade antibody to 100μl Dynabeads Protein G/A for 6+ hours at 4°C. Incubate antibody-bound beads with sheared chromatin overnight at 4°C with rotation. Wash beads sequentially with Low Salt Wash Buffer, High Salt Wash Buffer, and Final Wash Buffer [19].

DNA Recovery: Elute immunoprecipitated complexes with Elution Buffer, reverse cross-links by incubating with 5M NaCl at 65°C overnight, treat with Proteinase K, and purify DNA using phenol:chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation [19].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing library using 10-15ng of immunoprecipitated DNA, following manufacturer's protocols for your specific sequencing platform. Use minimal PCR cycles (8-12) to avoid amplification biases. Sequence using appropriate platform (Illumina recommended) to achieve 10-20 million mapped reads per sample [19] [18].

Revolutionizing Transcription Factor Binding Site Discovery

Genome-Wide Binding Maps

ChIP-seq has enabled the creation of comprehensive transcription factor binding maps across diverse biological systems. In a landmark study, the technology identified 41,582 and 11,004 putative STAT1-binding regions in interferon γ-stimulated and unstimulated human HeLa S3 cells, respectively, discovering 71% of known STAT1 interferon-responsive binding sites [9]. The modENCODE Consortium used ChIP-seq to map genome-wide binding sites for 22 transcription factors at diverse developmental stages in C. elegans, revealing that typical binding sites were predominantly located within a few hundred nucleotides of transcript start sites [9].

Elucidating Transcriptional Networks

Beyond simple binding site identification, ChIP-seq has revealed complex transcriptional networks. In prostate cancer cells, global binding maps of androgen receptor (AR) and commonly over-expressed transcriptional corepressors including HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3 revealed that "HDACs are directly involved in androgen-regulated transcription and wired into an AR-centric transcriptional network via a spectrum of distal enhancers and/or proximal promoters" [9]. This network analysis provided critical insights into how AR activity mediates repression of epithelial differentiation genes and promotes metastasis.

Comparative Analysis of Quantitative Findings

The quantitative nature of ChIP-seq data enables direct comparison of transcription factor binding across biological conditions.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Findings from Transcription Factor ChIP-seq Studies

| Biological System | Transcription Factor | Key Finding | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human HeLa S3 Cells [9] | STAT1 | 41,582 binding sites in IFNγ-stimulated vs 11,004 in unstimulated cells | Comprehensive mapping of stimulus-dependent TF binding |

| C. elegans Development [9] | 22 TFs | Binding sites concentrated near transcription start sites | Revealed spatial organization of regulatory landscape |

| Prostate Cancer Cells [9] | Androgen Receptor | HDAC corepressors integrated into AR network | Identified therapeutic targets for metastatic prostate cancer |

| NF-κB Signaling [9] | p65 subunit | Lysine methylation regulates differential gene binding | Unveiled post-translational mechanisms of specificity |

Analytical Revolution: From Data to Biological Insight

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biological insights requires sophisticated computational approaches.

Figure 2: ChIP-seq Computational Analysis Pipeline. Following sequencing, data undergoes quality control, alignment to a reference genome, peak calling to identify enriched regions, and differential binding analysis to compare conditions [20] [21] [17].

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Several sophisticated statistical methods have been developed specifically for ChIP-seq data analysis:

MAnorm: Designed for quantitative comparison of ChIP-seq datasets, MAnorm uses common peaks between samples as an internal reference to build a rescaling model for normalization, effectively addressing differences in signal-to-noise ratios between experiments [21].

ChIPComp: A comprehensive statistical method that accounts for genomic background (using control data), signal-to-noise ratios, biological variations, and multiple-factor experimental designs when performing quantitative comparison of multiple ChIP-seq datasets [20].

Virtual ChIP-seq: A predictive approach that forecasts transcription factor binding in new cell types by learning from associations with gene expression and publicly available ChIP-seq data, potentially reducing experimental burden [15].

Quality Assessment and Standards

The ENCODE and modENCODE consortia have established rigorous guidelines for ChIP-seq experiments [18]:

Antibody Validation: Antibodies must be characterized using immunoblot analysis or immunofluorescence, with the primary reactive band containing at least 50% of signal observed on blot [18].

Experimental Replication: Biological replicates are essential, with high consistency between replicates (typically Pearson correlation >0.9) [18].

Sequencing Depth: Recommended 10-20 million mapped reads per transcription factor ChIP-seq sample for mammalian genomes [18].

Control Experiments: Appropriate controls include "mock IP" using non-specific IgG, input DNA (non-immunoprecipitated genomic DNA), or wild-type samples when using epitope-tagged proteins [19] [18].

Transformative Applications in Transcription Factor Biology

Mechanisms of Differential Gene Regulation

ChIP-seq has enabled researchers to move beyond simple binding site identification to understand how transcription factors achieve specificity and regulate distinct gene sets. Studies on the p65 subunit of NF-κB have used ChIP-seq to investigate how lysine methylation regulates specific subsets of target genes, revealing how post-translational modifications direct transcription factors to distinct genomic locations [9].

Correlation with Gene Expression

Integration of ChIP-seq data with transcriptomic analyses has demonstrated strong correlation between transcription factor binding and gene expression changes. MAnorm analysis of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac in different cell types showed that "target genes associated with positive M values - that is, peaks with higher H3K4me3 and H3K27ac read intensity in cell type 1 - were enriched in genes more highly expressed in cell type 1" [21]. This quantitative relationship between binding intensity and expression output has been crucial for distinguishing functional binding events from non-functional interactions.

Disease-Relevant Transcriptional Networks

In disease contexts, particularly cancer, ChIP-seq has illuminated how transcriptional networks are rewired. The AR-centric transcriptional network in prostate cancer cells identified through ChIP-seq has provided critical insights for developing targeted therapies [9]. Similarly, understanding how oncogenic transcription factors bind genome-wide has advanced our knowledge of cancer mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions.

The revolution in transcription factor biology initiated by ChIP-seq continues to evolve through technical improvements and integrative approaches. Methods like Virtual ChIP-seq now predict transcription factor binding in new cell types by learning from transcriptomic data and existing ChIP-seq datasets, potentially extending these analyses to primary patient samples where cell numbers are limiting [15]. The integration of ChIP-seq with other functional genomics approaches—including ATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility, RNA-seq for gene expression, and CRISPR-based functional screens—provides increasingly comprehensive views of transcriptional regulation.

In conclusion, ChIP-seq has fundamentally transformed transcription factor biology by providing an unbiased, genome-wide view of protein-DNA interactions in their native chromatin context. This technology has enabled researchers to move from studying individual promoter elements to understanding complex transcriptional networks, from qualitative assessments of binding to quantitative comparisons across cellular states, and from phenomenological observations of gene regulation to mechanistic insights into transcriptional control. As the technology continues to evolve and integrate with other functional genomics approaches, ChIP-seq will remain a cornerstone method for elucidating the fundamental principles of gene regulation in health and disease.

In eukaryotic gene regulation, enhancers and promoters serve as the primary genomic determinants of temporal and spatial transcriptional specificity. These cis-regulatory elements (CREs) orchestrate precise gene expression patterns despite often being separated by vast genomic distances, sometimes exceeding one megabase [22]. The discovery of how these elements communicate through three-dimensional chromatin architecture has revolutionized our understanding of gene regulation. This application note frames these concepts within the context of Transcription Factor (TF) ChIP-seq research, providing both theoretical frameworks and practical methodologies for researchers investigating gene regulatory mechanisms. The ENCODE consortium has interrogated nearly a million putative CREs in the human genome, yet defining their functional interactions remains a central challenge in genomics [23] [22].

For TF ChIP-seq research, understanding the spatial organization of chromatin is paramount, as TF binding sites frequently reside within enhancers, and their functional impact depends on their ability to communicate with target promoters through chromatin looping [23]. This note integrates current understanding of enhancer-promoter interactions with practical experimental and computational approaches to study these phenomena, emphasizing standardized protocols that ensure data reproducibility and quality.

Current Research Landscape and Quantitative Data

Biases in Existing TF ChIP-seq Data

Publicly available human TF ChIP-seq datasets demonstrate significant coverage biases. As of October 2023, the ChIP-Atlas database contained 27,865 ChIP-seq experiments covering 1,810 target TFs across 1,126 cell types. Quantitative analysis reveals substantial inequality in experimental coverage, with Gini coefficients of 0.77 for TFs and 0.82 for cell types, indicating strong skew toward certain TFs and cell lines [1].

Table 1: Distribution of TF ChIP-seq Experiments Across Cell Type Classes

| Cell Type Class | Number of ChIP-seq Experiments | Number of Unique TFs Targeted |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Highest | 801 |

| Embryo | Lowest | 15 |

| Multiple Classes | 27,865 (total) | 1,810 (total) |

This inequality stems from both combinatorial complexity (with ~1,600 TFs across ~400 cell types creating immense possible pairs) and technical constraints including antibody availability and large cell number requirements (~1-10 million cells per experiment) [1]. A machine learning model revealed that publication frequency (a proxy for research attention) strongly predicts which TFs are targeted, with a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.69 between publication count and ChIP-seq experiments, indicating a "rich-get-richer" effect in research focus [1].

The Challenge of Unmeasured TF-Sample Pairs

The concept of "unmeasured TF-sample pairs" – biologically relevant combinations of TFs and cell types where ChIP-seq experiments haven't been performed – highlights significant gaps in our understanding of the functional genomic landscape [1]. This incomplete coverage affects downstream analyses including regulatory region coverage and interpretation of genome-wide association study (GWAS) SNPs. Systematic expansion of TF ChIP-seq datasets is essential for comprehensive understanding of gene regulatory mechanisms, particularly for clinical applications linking noncoding variants to disease [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ENCODE TF ChIP-seq Standards and Pipeline

The ENCODE consortium has established rigorous standards for TF ChIP-seq experiments to ensure data quality and reproducibility [7].

Table 2: ENCODE TF ChIP-seq Experimental Standards

| Parameter | Minimum Requirement | Preferred Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Replicates | 2 (isogenic or anisogenic) | 2 or more |

| Usable Fragments per Replicate | 10 million (low depth) | 20 million |

| Read Length | 50 base pairs | Longer read lengths encouraged |

| Library Complexity (NRF) | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients | PBC1>0.9, PBC2>3 | PBC1>0.9, PBC2>10 |

| Replicate Concordance | IDR rescue and self-consistency ratios <2 | IDR rescue and self-consistency ratios <2 |

The ENCODE TF ChIP-seq pipeline involves two major stages: (1) mapping of FASTQ files to a reference genome, and (2) peak calling for identification of TF binding sites. The pipeline outputs include signal coverage tracks (fold change over control and signal p-value), peak calls (relaxed, conservative IDR, and optimal IDR peaks), and comprehensive quality control metrics [7].

Mapping Enhancer-Promoter Interactions

Multiple advanced methodologies enable the study of EPIs, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

3C-based Methods: Chromatin Conformation Capture (3C) and its derivatives (4C-seq, Hi-C, PLAC-seq, Capture-C, micro-C) involve proximity ligation of digested chromosomes in crosslinked cells to identify spatially proximal genomic regions [22]. These methods have revealed fundamental features of genomic organization including territories, A/B compartments, topologically associating domains (TADs), and chromatin loops.

Ligation-free Approaches: Techniques including SPRITE (split-pool recognition of interactions by tag extension), GAM (genome architecture mapping), and ChIA-Drop survey multiway chromosomal contacts without ligation, overcoming artifacts associated with proximity ligation [22].

Imaging-based Methods: Advanced microscopy techniques including super-resolution microscopy combined with multiplexed probes (OligoFISSEQ, MERFISH) enable visualization of interactions involving >1000 genomic loci at 10-100 kb resolution in single cells [22]. Live-cell imaging extends this to dynamic visualization over time.

Integrating AI for 3D Genome Prediction

Recent advances employ generative artificial intelligence to predict 3D genome structures from DNA sequence. The ChromoGen model combines a deep learning component that "reads" the genome with a generative AI component that predicts physically accurate chromatin conformations [24]. This approach can predict thousands of structures in minutes compared to days or weeks for experimental methods, enabling rapid exploration of how mutations alter chromatin conformation and potentially cause disease [24].

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Distance-Dependent Regulation of Enhancer-Promoter Communication

Recent research reveals that protein regulators facilitate EP communication in a distance-dependent manner. A comprehensive study combining E-P distance-controlled reporter screens with protein inhibition demonstrated that cohesin, transcription factors, and mediator complex components regulate gene expression with distinct distance dependencies [23].

Table 3: Distance-Dependent Effects of Protein Regulators on E-P Communication

| Protein Complex | Effect on Short-Range E-P | Effect on Long-Range E-P | Molecular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesin (SMC1A, SMC3, RAD21, STAG2) | Increased expression | Decreased expression | Loop extrusion, TAD formation |

| Mediator Complex (MED14, etc.) | Moderate negative effect | Pronounced negative effect | Bridge between TFs and RNA Pol II |

| Tissue-specific TFs (LDB1, etc.) | No clear distance bias | No clear distance bias | Direct DNA binding, complex assembly |

Cohesin complex depletion specifically downregulates long-range controlled genes (50-500 kb) while upregulating short-range genes (<10 kb), indicating that E-P distance, rather than enhancer strength, is the key factor for cohesin sensitivity [23]. This distance-dependent regulation ensures precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression during development and cellular differentiation.

Mechanisms of Enhancer-Promoter Interaction

Multiple mechanisms facilitate the bringing together of distal enhancers and promoters:

- Passive 3D diffusion - Random collision within nuclear space

- Active loop extrusion without CTCF sites - Cohesin-mediated extrusion at enhancers and promoters

- Loop extrusion with facilitating CTCF sites - Cohesin-mediated extrusion stalled by CTCF binding

- Specific looping factors - Proteins like LDB1 that directly facilitate looping

These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and likely operate simultaneously, with each showing distinct sensitivity to the loss of specific protein regulators and distinct distance dependence [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Enhancer-Promoter and 3D Genomics Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TF-specific antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of TF-DNA complexes | Must be characterized per ENCODE standards; limited availability for many TFs |

| Control antibodies (IgG) | Negative control for immunoprecipitation | Should match species and isotype of primary antibody |

| Protein A/G magnetic beads | Capture antibody-bound complexes | Enable efficient pulldown and washing |

| Crosslinking agents (formaldehyde) | Fix protein-DNA interactions | Standard concentration: 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes |

| Chromatin shearing reagents | Fragment chromatin to 200-600 bp | Enzymatic (MNase) or sonication-based methods |

| Hi-C library preparation kit | Proximity ligation of crosslinked DNA | Commercial kits available from multiple vendors |

| SPRITE barcoding reagents | Multiplexed tagging of interacting regions | Enables detection of multiway contacts |

| MERFISH probes | Multiplexed imaging of genomic loci | Requires design of target-specific probe sets |

| dCas9-effector systems | Epigenome editing at specific loci | Enables functional validation of CREs |

Application in Disease and Development Contexts

Transcriptional Reprogramming in Muscle Fiber Specification

Integrative analysis of transcriptome, epigenome, and 3D genome architecture in slow-twitch glycolytic (EDL) and fast-twitch oxidative (SOL) muscles revealed that global remodeling of E-P interactions drives transcriptional reprogramming associated with muscle contraction and glucose metabolism [25]. Tissue-specific super-enhancers regulate muscle fiber-type specification through cooperation of chromatin looping and transcription factors such as KLF5. Notably, SE-driven activation of STARD7 facilitates transformation of glycolytic fibers into oxidative fibers by mitigating reactive oxygen species levels and suppressing ERK MAPK signaling [25].

This research demonstrates how activated CREs and 3D genome organization direct phenotypic specification, providing a foundation for novel therapeutic strategies targeting metabolic disorders. The findings have implications for both human health (obesity, Type 2 diabetes) and agricultural applications (meat quality enhancement) [25].

Implications for Enhancer-Related Diseases

Dysregulation of enhancers is a major cause of diseases and developmental defects [22]. Understanding the mechanistic basis of lineage- and context-dependent E-P engagement provides insights into the spatiotemporal control of gene expression that can reveal therapeutic opportunities for a range of enhancer-related diseases. Continued identification of functional enhancers and their target genes remains crucial for connecting noncoding genetic variation to phenotypic outcomes.

The integration of TF ChIP-seq with 3D chromatin architecture data provides unprecedented insights into the spatial organization of gene regulation. As research moves toward more comprehensive coverage of TF-sample pairs and more sophisticated predictive models, our ability to interpret the functional consequences of genetic variation in regulatory elements will continue to improve. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a roadmap for researchers exploring the intricate relationships between enhancers, promoters, and the three-dimensional genome.

Executing ChIP-seq: Protocols, Pipelines, and Practical Applications

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has revolutionized our ability to map protein-DNA interactions genome-wide. For transcription factor (TF) binding research, consistency in data processing is paramount to ensure reproducibility and reliable biological interpretation. The ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) Consortium has established a standardized transcription factor ChIP-seq pipeline specifically designed for proteins that bind DNA in a punctate manner, providing the community with a robust framework for generating high-quality, comparable data [7]. This pipeline represents a cornerstone in the field, enabling integrative analyses and meta-analyses across different laboratories and experimental conditions.

The development of this uniform processing pipeline addresses the critical challenge of variability in how ChIP-seq experiments are conducted, scored, and evaluated [18]. By implementing consistent methods for signal and peak calling, along with standardized statistical treatment of replicates, the ENCODE TF pipeline has become an essential resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand transcriptional regulation in health and disease.

Pipeline Architecture

The ENCODE transcription factor ChIP-seq pipeline was developed as part of the ENCODE Uniform Processing Pipelines series, sharing initial mapping steps with the histone modification pipeline but employing distinct methods for signal and peak calling that are optimized for punctate binding patterns [7]. This specialized approach recognizes the fundamental differences in how transcription factors interact with DNA compared to broader histone marks, requiring tailored algorithms for accurate binding site identification.

The pipeline is designed with portability across computing environments, supporting execution on various cloud platforms (Google, AWS, DNAnexus) and cluster engines (SLURM, SGE, PBS) [26]. This flexibility ensures broad accessibility while maintaining processing consistency. The code is publicly available on GitHub, and the workflow has been deposited to platforms including Dockstore, Truwl, and Seven Bridges, further enhancing reproducibility and adoption [27] [26].

Quality Control Standards

The ENCODE Consortium has established rigorous quality control metrics and thresholds to ensure data reliability. Library complexity is measured using the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 and PBC2), with preferred values of NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 [7]. These metrics help identify potential issues with over-amplification or insufficient sequencing depth that could compromise downstream analyses.

For transcription factor experiments specifically, the consortium recommends 20 million usable fragments per biological replicate as the optimal sequencing depth, with lower thresholds categorized as "low read depth" (10-20 million), "insufficient" (5-10 million), or "extremely low" (<5 million) [7]. Replicate concordance is quantitatively assessed using Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis, with experiments passing quality thresholds when both rescue and self-consistency ratios are less than 2 [7].

Table 1: ENCODE TF ChIP-seq Quality Control Standards

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Preferred Threshold | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Complexity | Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) | > 0.9 | Indicates minimal PCR duplication bias |

| PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 1 (PBC1) | > 0.9 | Measures library complexity | |

| PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 2 (PBC2) | > 10 | Assesses amplification efficiency | |

| Sequencing Depth | Usable fragments per replicate | 20 million | Ensures sufficient coverage for binding site detection |

| Replicate Concordance | IDR rescue ratio | < 2 | Measures consistency between biological replicates |

| IDR self-consistency ratio | < 2 | Assesses internal reproducibility |

Experimental Design Requirements

The pipeline mandates specific experimental design elements to ensure data quality and interpretability. The consortium strongly recommends two or more biological replicates for each experiment, acknowledging that assays using EN-TEx samples may be exempted due to limited material availability [7]. This replication strategy is crucial for distinguishing reproducible binding events from technical artifacts or irreproducible findings.

Antibody validation represents another critical component of the experimental framework. The consortium has established target-specific standards requiring thorough characterization of antibodies according to defined specifications [7] [18]. For transcription factors, primary characterization typically involves immunoblot analysis or immunofluorescence to confirm specificity and minimal cross-reactivity [18]. Each ChIP-seq experiment must also include a corresponding input control experiment with matching run type, read length, and replicate structure to account for technical biases and background signal [7].

Processing Workflow and Methodologies

Input Requirements and Data Preparation

The ENCODE TF pipeline accepts FASTQ files as primary inputs, accommodating both paired-end and single-end sequencing data, with a minimum read length requirement of 50 base pairs (though the pipeline can process reads as short as 25 bp) [7]. Before mapping, multiple FASTQ files from a single biological replicate or library are concatenated to create comprehensive datasets for processing. The pipeline is designed to map reads to specific reference genomes, primarily GRCh38 for human and mm10 for mouse, utilizing corresponding genome indices provided in FASTA format [7].

Critical to the processing workflow is the inclusion of appropriate control datasets. The pipeline requires a control BAM file (typically from input DNA, IgG, or other control experiments) that matches the experimental samples in run type, read length, and replicate structure [7]. This control file enables the normalization and background correction essential for accurate peak calling.

Table 2: Input Requirements for ENCODE TF ChIP-seq Pipeline

| Input Type | Format | Requirements | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Reads | FASTQ (gzipped) | Minimum 50 bp read length; Paired-end or single-end; Platform specified | Primary data for mapping |

| Genome Reference | FASTA | GRCh38 or mm10 assembly; Genome indices | Read alignment reference |

| Control Experiment | BAM | Filtered alignments from control; Matching run type and replicate structure | Background signal normalization |

Mapping and Peak Calling Methodology

The initial mapping phase processes concatenated FASTQ files through optimized alignment steps, producing BAM files containing the aligned reads [7]. These aligned files then serve as inputs for the transcription factor-specific peak calling phase, which differs significantly from the approach used for histone marks.

The peak calling algorithm generates two versions of nucleotide-resolution signal coverage tracks in bigWig format: fold change over control and signal p-value [7]. The fold change track represents the enrichment of ChIP signal relative to the control, while the p-value track assesses the statistical significance of this enrichment at each genomic position. For peak identification, the pipeline initially produces relaxed peak calls (in narrowPeak format) for each replicate individually and for pooled replicates, intentionally including potential false positives to facilitate subsequent statistical comparison of replicates [7].

Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) Analysis

A cornerstone of the ENCODE TF pipeline is its sophisticated handling of replicate concordance through Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis. This statistical approach measures the reproducibility of identified peaks across biological replicates, effectively ranking binding events by their consistency [7].

The pipeline generates two primary peak sets through IDR analysis: conservative IDR peaks and optimal IDR peaks [7]. The conservative set represents the most reproducible binding events, while the optimal set provides a larger collection of peaks that still meet reproducibility thresholds. This tiered approach allows researchers to select stringency levels appropriate for their specific biological questions. For experiments without true biological replicates, the pipeline employs a pseudoreplicate strategy, partitioning data to estimate reproducibility [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete ENCODE TF ChIP-seq data processing pathway:

Workflow of the ENCODE TF ChIP-seq data processing pipeline, showing key stages from raw data to final output.

Outputs and Data Interpretation

File Formats and Data Visualization

The ENCODE TF pipeline generates several standardized output files designed for visualization and downstream analysis. The primary signal tracks are produced in bigWig format, providing two complementary representations of the ChIP-seq signal: fold change over control and signal p-value [7]. These tracks enable quantitative assessment of binding enrichment across the genome and are compatible with major genome browsers for intuitive visualization.

Peak calls are delivered in both BED and bigBed (narrowPeak) formats, with distinct files for different stringency levels [7]. The relaxed peak sets serve as input for statistical comparison rather than definitive binding calls, while the IDR-thresholded peaks represent reproducible binding events. This multi-tiered approach provides flexibility for different analytical needs, from comprehensive binding landscape characterization to focused analysis of high-confidence sites.

Quality Assessment and Metrics

Comprehensive quality control metrics are collected throughout the pipeline execution, providing researchers with essential information for evaluating data quality. Key metrics include library complexity measurements (NRF, PBC1, PBC2), read depth statistics, Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) scores, and reproducibility measures [7]. The pipeline generates an HTML report that tabulates these metrics alongside informative visualizations such as IDR plots and cross-correlation measures [26].

For researchers working with multiple datasets, tools like qc2tsv can compile metrics from multiple qc.json files into a consolidated spreadsheet format, facilitating comparative analysis across experiments [26]. This standardized reporting ensures consistent quality assessment and enables identification of potential technical issues that might compromise biological interpretations.

Table 3: Key Output Files from ENCODE TF ChIP-seq Pipeline

| Output File | Format | Description | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Tracks | bigWig | Fold-change over control and p-value tracks | Genome browser visualization; Signal quantification |

| Relaxed Peaks | BED/bigBed (narrowPeak) | Initial peak calls for individual and pooled replicates | Input for replicate comparison; Exploratory analysis |

| Conservative IDR Peaks | BED/bigBed (narrowPeak) | High-confidence peaks from IDR analysis | High-specificity binding site identification |

| Optimal IDR Peaks | BED/bigBed (narrowPeak) | Larger peak set from IDR analysis | Balanced sensitivity/specificity for most applications |

| QC Report | HTML/JSON | Comprehensive quality metrics and visualizations | Data quality assessment; Experiment evaluation |

Implementation Protocols

Pipeline Execution Methods

The ENCODE TF ChIP-seq pipeline can be executed through multiple computational environments to accommodate different infrastructure preferences. For Docker-based execution, the basic command structure is: caper run chip.wdl -i "${INPUT_JSON}" --docker --max-concurrent-tasks 1 [26]. The --max-concurrent-tasks 1 parameter is recommended for computers with limited resources, such as personal workstations or laptops.

For high-performance computing (HPC) environments with Singularity support, the pipeline can be submitted as a leader job to cluster schedulers (SLURM, SGE, PBS) using: caper hpc submit chip.wdl -i "${INPUT_JSON}" --singularity --leader-job-name ANY_GOOD_LEADER_JOB_NAME [26]. Job status can be monitored using caper hpc list, and jobs can be terminated with caper hpc abort [JOB_ID] to ensure proper cleanup of all child processes.

Input JSON Configuration

Proper configuration of the input JSON file is critical for successful pipeline execution. This file must specify all input parameters and files using absolute paths rather than relative paths [26]. Essential parameters include paths to FASTQ files, genome reference specifications, pipeline type (tf for transcription factor), paired-end status, and control sample information.

When preparing the input JSON, researchers must carefully define the pipeline_type as "tf" for transcription factor experiments, specify paired_end status appropriately, and ensure that control parameters (ctl_paired_end) match the experimental data [26]. The genome reference must be specified using a dedicated genome TSV file that provides paths to required genome-specific data such as aligner indices, chromosome sizes, and blacklist regions.

Output Organization and Analysis

After pipeline execution, output files can be organized using Croo, a specialized tool that processes the metadata JSON file generated by Caper to create a structured directory hierarchy: croo [METADATA_JSON_FILE] [26]. This organization facilitates location of specific output files and ensures consistent structure across multiple pipeline runs.

The final output includes the organized peak files, signal tracks, and quality metrics in the qc/qc.json file [26]. This standardized output structure enables seamless integration with downstream analysis tools and comparative studies. For multi-experiment analysis, qc2tsv can transform multiple QC JSON files into a tabular format suitable for statistical analysis and visualization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ENCODE TF ChIP-seq

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Function | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Target-validated; Lot-specific characterization | Immunoprecipitation of target transcription factor | Immunoblot with >50% signal in expected band; Immunofluorescence validation [18] |

| Control Samples | Input DNA or IgG; Matching replicate structure | Background signal normalization; Experimental control | Must match experimental samples in read length and run type [7] |

| Genome References | GRCh38 (human) or mm10 (mouse) | Read alignment reference | Standardized indices and blacklist regions [7] [26] |

| Cell Lines/Tissues | Well-characterized; Appropriate for target TF | Biological source for ChIP experiment | Documentation of passage number, growth conditions, and authentication [18] |

| Sequencing Libraries | Minimum 50 bp read length; Paired-end preferred | Detection of immunoprecipitated DNA | Library complexity metrics (NRF>0.9, PBC1>0.9, PBC2>10) [7] |

The ENCODE Transcription Factor ChIP-seq pipeline represents a comprehensive, standardized approach for identifying transcription factor binding sites with high reproducibility and reliability. Through its specialized processing methods, rigorous quality controls, and sophisticated replicate analysis via IDR, the pipeline addresses critical challenges in ChIP-seq data generation and interpretation. The availability of this standardized framework across multiple computing platforms ensures broad accessibility while maintaining consistency in data processing.

As transcription factor binding research continues to evolve, with emerging considerations such as DNA modification sensitivities [28] and combinatorial binding patterns [29] [30], the robust foundation provided by the ENCODE pipeline enables researchers to build increasingly sophisticated analyses. The continued development and refinement of these standardized processing methods will remain essential for advancing our understanding of transcriptional regulation and its implications in development, cellular function, and disease.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a powerful technique that captures a snapshot of where specific proteins interact with DNA across the entire genome, providing fundamental insights into gene regulation, epigenetic mechanisms, and disease pathogenesis [10]. For transcription factor (TF) binding research, it enables the genome-wide identification of transcription factor binding sites, revealing the regulatory networks that control cellular processes [7] [10]. This application note details a standardized workflow from raw sequencing data to the identification of significant protein-DNA binding events, framed within the context of a broader thesis on ChIP-seq for transcription factor binding research. The protocols and quality metrics presented here align with established consortium guidelines and have been validated in published studies [7] [31].

The analytical journey of a ChIP-seq experiment can be broken down into a logical sequence of steps: initial quality assessment of raw sequencing reads, alignment to a reference genome, filtering to obtain high-quality mapped reads, and finally, peak calling to identify significant regions of enrichment [10] [32]. The following diagram illustrates this complete workflow, including key quality control checkpoints.

Preprocessing: From Raw Reads to Aligned Data

Initial Quality Control and Read Trimming

The first critical step is to assess the quality of the raw sequencing data using tools such as FastQC [33] [32]. This evaluation checks for per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and overall sequence complexity. Following quality assessment, reads are trimmed to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools like Trim Galore or Cutadapt [10] [32]. This ensures that only high-quality data proceeds to alignment, which is crucial for accurate mapping.

Read Alignment to a Reference Genome

The trimmed reads are then aligned to a reference genome (e.g., hg38 for human) to determine their genomic origins. For ChIP-seq data, aligners such as Bowtie2 [5] and BWA [10] are standard choices. The ENCODE mapping pipeline requires a minimum read length of 50 base pairs, though it can process reads as short as 25 base pairs [7]. The output of this step is a Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) or its binary equivalent (BAM) file, containing the genomic coordinates for each read.

Table 1: Recommended Alignment Tools and Key Parameters [33] [7] [10]

| Tool | Recommended Use | Key Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowtie2 | Standard global alignment for ChIP-seq reads. | Default parameters typically sufficient. -X 2000 (for PE, max fragment length). |

SAM/BAM |

| BWA | Alternative well-established aligner. | Standard algorithm for single-end reads. | SAM/BAM |

Post-Alignment Processing and Filtering

After alignment, the BAM files require several processing steps to ensure the data is suitable for peak calling:

- Sorting and Indexing: BAM files are coordinate-sorted and indexed using

samtoolsto enable efficient visualization and access [10]. - Duplicate Removal: PCR duplicates are marked or removed using tools like Picard or

samtoolsto prevent artificial inflation of read counts in specific regions [33]. - Blacklist Filtering: Reads mapping to "blacklisted" regions (e.g., hyper-chippable regions, ENCODE blacklists) are discarded to reduce false positives [33] [34].

Peak Calling and Quality Assessment

Identifying Regions of Enrichment

Peak calling is the process of identifying genomic regions where the number of aligned ChIP-seq reads is significantly enriched compared to a background control (input DNA) [32]. The choice of algorithm depends on the binding profile of the protein of interest. For punctate transcription factor binding sites, MACS2 (Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq) is the most widely used and recommended tool [14] [33] [32]. The ENCODE transcription factor pipeline utilizes MACS2 for its effectiveness in identifying narrow peaks [7].

Table 2: Peak-Calling Tools and Applications [14] [33] [35]

| Tool | Primary Application | Key Features / Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACS2 | Transcription Factors (narrow peaks) | -q 0.005 (q-value threshold), --nomodel, --shift 100, --extsize 200 [33] |

BED/narrowPeak |

| Genrich | ATAC-seq; can be used for ChIP-seq | -j (ATAC-seq mode), can process multiple replicates jointly |

BED/narrowPeak |

| SICER | Broad histone marks | Designed for diffuse, broad domains. | BED |

| WonderPeaks | Novel algorithm for various data | Uses first derivative of mapped data. | BED |

Essential Quality Control Metrics

Rigorous quality control is imperative to validate the success of a ChIP-seq experiment. Several metrics have been established by the ENCODE consortium and other authorities to assess data quality [7] [31].

- Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP): This measures the fraction of all mapped reads that fall within peak regions. A higher FRiP score indicates a stronger enrichment. ENCODE guidelines suggest FRiP scores should be > 0.3 for transcription factor ChIP-seq, though > 0.2 is acceptable [33] [7].

- Strand Cross-Correlation: This analysis assesses the clustering of reads on forward and reverse strands around binding sites. It produces two key metrics: the Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) and the Relative Strand Correlation (RSC). For sharp transcription factor peaks, an NSC > 5.0 and an RSC > 1.0 are indicative of a high-quality experiment [5] [32]. Input controls should have low signal-to-noise and thus lower NSC values (e.g., < 2.0) [32].

- Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR): For experiments with biological replicates, IDR analysis compares peak lists to evaluate consistency between replicates. This statistical method helps generate a conservative, high-confidence set of peaks. The ENCODE pipeline uses IDR to define optimal and conservative peak sets for replicated experiments [7]. A recent study on G-quadruplex ChIP-seq data further highlighted that using at least three replicates significantly improves detection accuracy [36].

- Library Complexity: Measures like the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 and PBC2) assess the complexity of the library. Preferred values are NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10, indicating a low degree of PCR duplication and a high-quality library [7].

Table 3: Key ChIP-seq Quality Control Metrics and Thresholds [7] [36] [32]

| Metric | Description | Recommended Threshold (TF ChIP-seq) |

|---|---|---|

| FRiP | Fraction of Reads in Peaks | > 0.3 (acceptable > 0.2) |

| NSC | Normalized Strand Coefficient | > 5.0 (sharp peaks) |

| RSC | Relative Strand Correlation | > 1.0 |

| IDR | Irreproducible Discovery Rate | Pass threshold for replicate concordance |

| NRF | Non-Redundant Fraction | > 0.9 |

| Sequencing Depth | Mapped reads per replicate | Minimum 20 million (10-20M: low) [7] [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ChIP-seq experiment relies on both computational tools and wet-lab reagents. The table below details essential materials and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ChIP-seq

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Specific Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of the DNA-protein complex. Must be validated for ChIP-seq specificity and efficiency [7]. |

| Magnetic Protein A/G Beads | Capture of the antibody-bound complex during immunoprecipitation. |

| Input DNA (Control) | Genomic DNA prepared from sonicated cross-linked chromatin without immunoprecipitation. Serves as a critical control for peak calling [7]. |

| Cell Line/Tissue of Interest | Source of chromatin for the experiment. |

| Crosslinking Agent (e.g., Formaldehyde) | Stabilizes protein-DNA interactions in living cells prior to lysis and fragmentation. |

| Library Preparation Kit | Prepares the immunoprecipitated DNA for high-throughput sequencing (e.g., adds adapters, performs PCR amplification). |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The genomic sequence to which sequenced reads are aligned (e.g., GRCh38/hg38 for human) [7] [10]. |

| Genome Annotation (GTF/GFF) | File containing genomic feature coordinates (genes, promoters, etc.) used for annotating called peaks. |

This guide outlines a comprehensive and standardized protocol for analyzing ChIP-seq data from FASTQ files to a confident set of peaks. Adherence to established quality metrics, such as FRiP, strand cross-correlation, and IDR, is non-negotiable for drawing robust biological conclusions about transcription factor binding. By following this workflow, researchers can ensure their data meets the high standards required for publication and provides a reliable foundation for downstream functional analyses, such as motif discovery and integration with transcriptomic data, ultimately advancing our understanding of gene regulatory networks in health and disease.